Practices and Awareness of Disinformation for a Sustainable Education in European Secondary Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- H0 = There are no statistically significant differences between both independent samples (p > 0.05).

- H1 = There are statistically significant differences between both independent samples (p < 0.05).

2. State of Affairs

2.1. Disinformation and Fake News

2.2. Minors and Social Media

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Perceptions of Disinformation in Terms of Creation, Associations, and Distribution

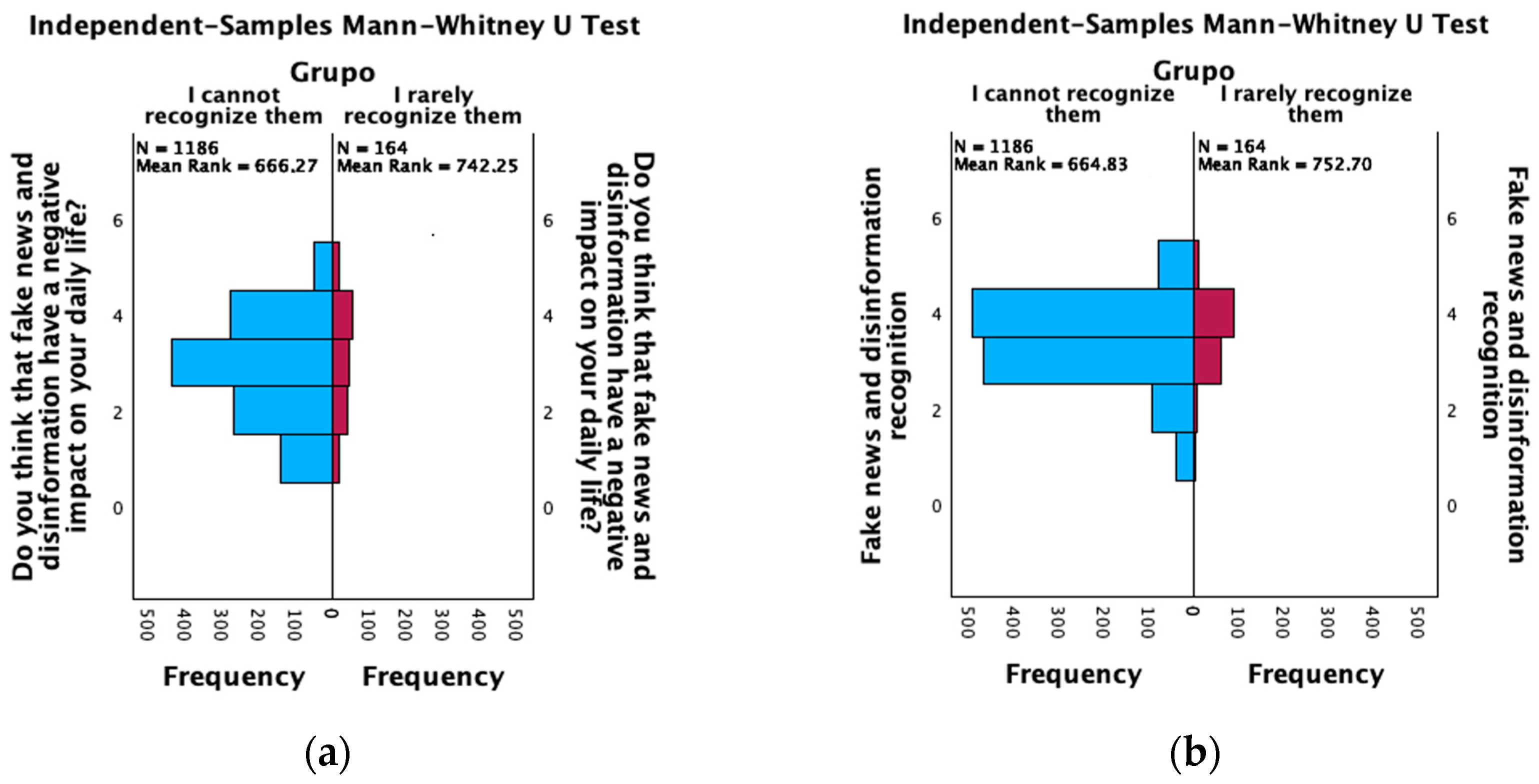

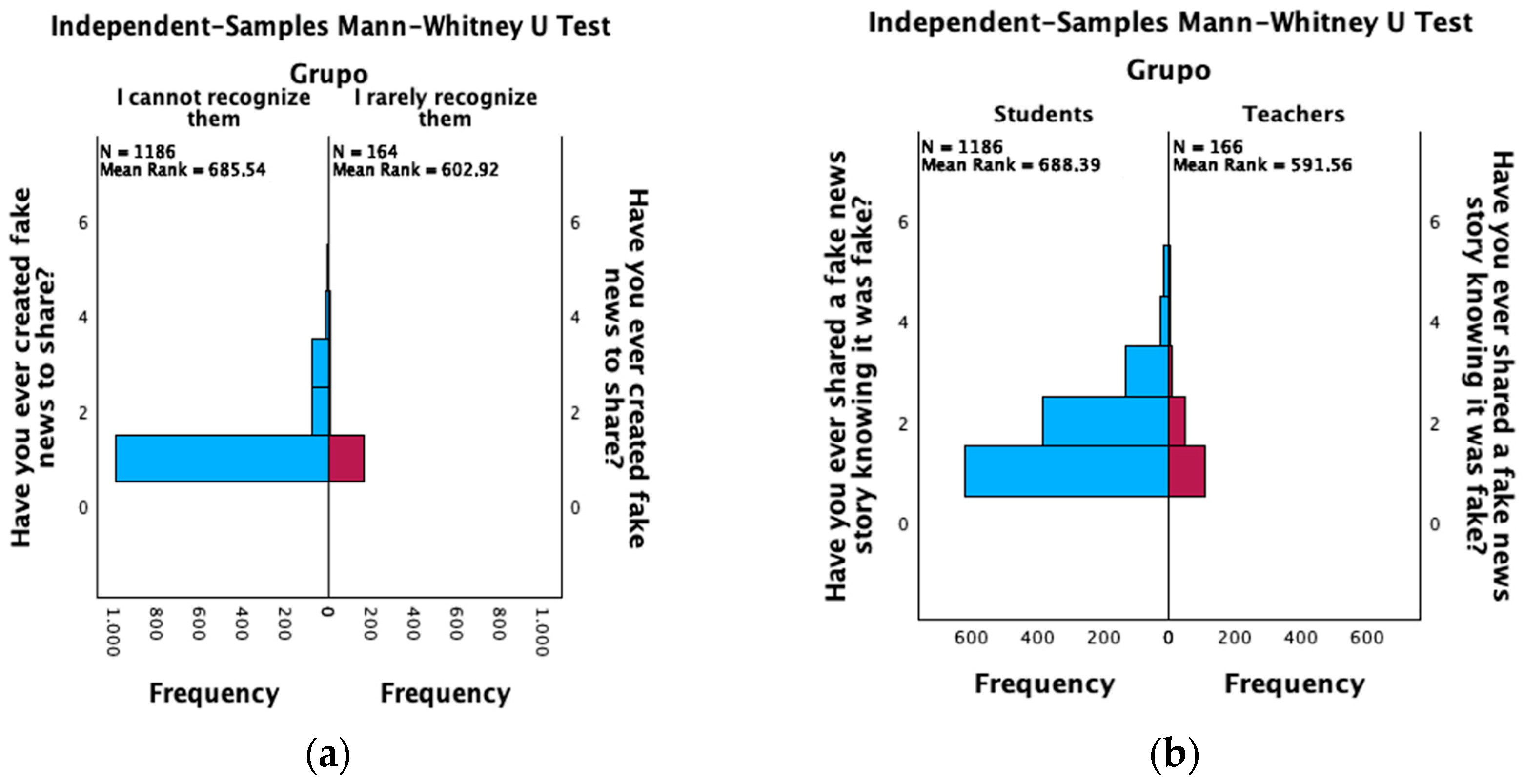

4.2. Feelings Towards Disinformation: Self-Impact, Ability to Recognize, Self-Creation, and Sharing

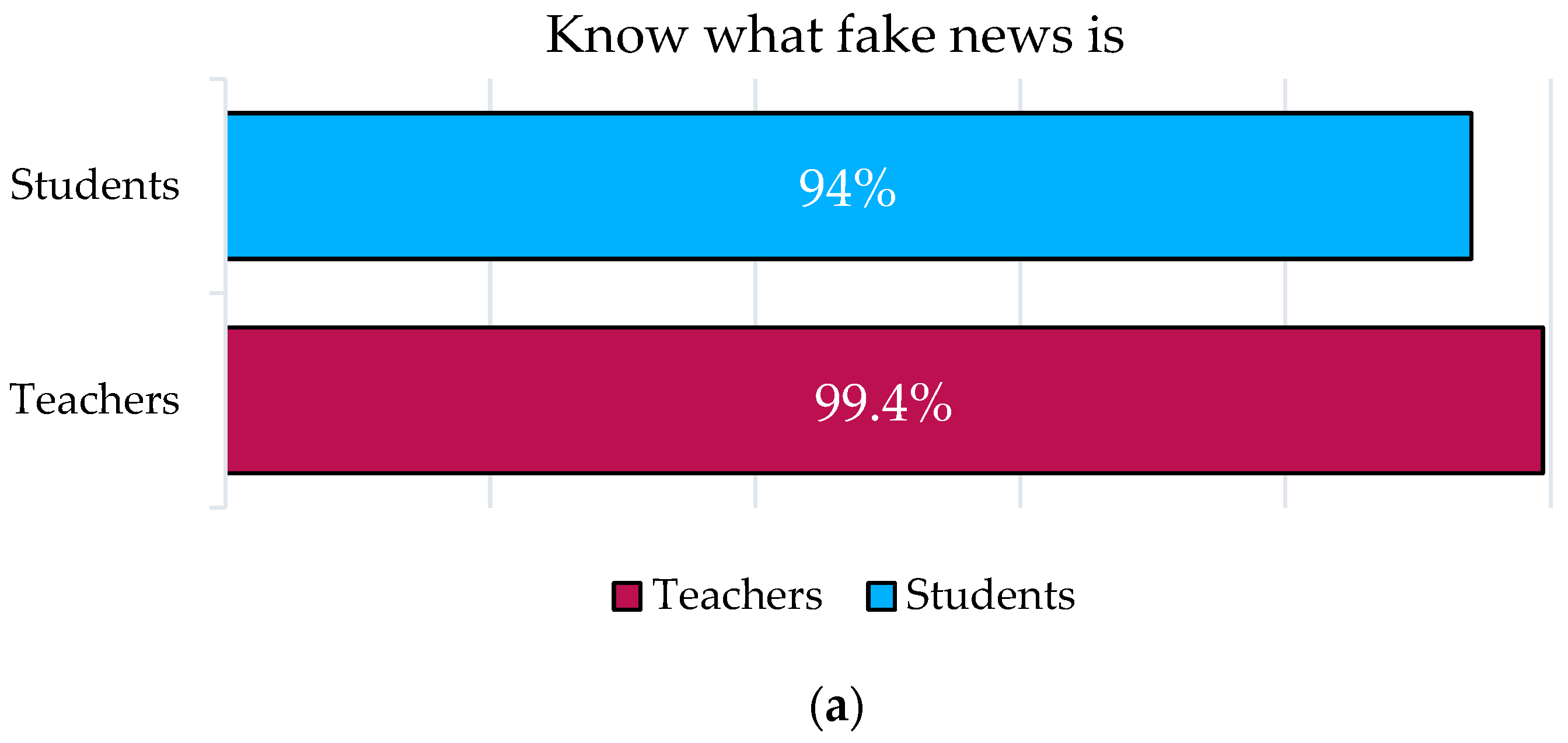

4.3. Knowledge and Management Perceived Regarding Fake News, Disinformation, and Related Terms

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Latif, A.; Zambri, W.; Latiff, D.; Kamal, S. Media Literacy and Digital Citizenship in the Era of Social Media. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrão, C.; Soeiro, D.; Parreiral, S. Media, literacy and education: Partners for sustainable development. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Communication and Sustainable Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier, A. Wanting to share: How integration of digital media literacy supports student participatory culture in 21st century sustainability education. J. Sustain. Educ. 2020, 24, 1–14. Available online: http://www.susted.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Bernier-JSE-December-2020-General-Issue-PDF.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Zurkowski, P. The Information Service Environment Relationships and Priorities; Related Paper No. 5; National Commission on Libraries and Information Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1974. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED100391 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Glister, P. Digital Literacy; Jhon Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union. L394/10. RECOMMENDATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 18 December 2006 on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (2006/962/EC). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:394:0010:0018:en:PDF (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Masterman, L. Teaching the Media; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ruiz, R.; Pérez-Escoda, A. Communication and Education in a digital connected world. J. ICONO 14 2020, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; y Rubio-Romero, J. Social Media: The Fifth Power. A Field-by-Field Approach to a Phenomenon That Has Transformed Public and Private Communication; Tirant Lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Promoting Healthy Behaviours and Mitigating the Harm from Misinformation and Disinformation. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- OECD. Future of Education and Skills 2030 Curriculum Database. OECD Learning Compass 2030. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/4dPTNj5 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Tackling Online Disinformation: A European Approach. COM/2018/236 Final. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0236 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- INCIBE (Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad) (s/f). Learn to Check: Una Plataforma Para Luchar Contra la Desinformación. Available online: https://www.incibe.es/ciudadania/blog/learn-check-una-plataforma-para-luchar-contra-la-desinformacion (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Reuters Institute. Digital News Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZszuDiwChZoSMhbjjJII29krPqYPQ6am/view (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- European Union. Digital Literacy in the EU. European Data. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/datastories/digital-literacy-eu-overview (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Magallón-Rosa, R.; Paisana, M. Disinformation Consumption Patterns in Spain and Portugal. Pamplona: IBERIFIER. 2024. Available online: https://iberifier.eu/2024/05/15/iberifier-reports-disinformation-consumption-patterns-in-spain-and-portugal/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- European Union. Guidelines for Teachers and Educators on Tackling Disinformation and Promoting Digital Literacy Through Education and Training. Publications Office of the European Union. 2022. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a224c235-4843-11ed-92ed-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Tandoc, E., Jr.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining “fake news”: A typology of scholarly definitions. Digit. J. 2017, 6, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Council of Europe. 2017. Available online: https://edoc.coe.int/en/media/7495-information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-research-and-policy-making.html (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Pariser, E. The filter bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Standard Eurobarometer 98. March 2023. Published in December 2023. Theme: Politics and the European Union: Democracy. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2966 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Jones-Jang, S.M.; Mortensen, T.; Jingjing, L. Does Media Literacy Help Identification of Fake News? Information Literacy Helps, but Other Literacies Don’t. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Haenens, L.; Ioris, W. Media Literacy in a Digital Age: Taking Stock and Empowering Action. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAB Spain. XV Edición Estudio Redes Sociales 2024. 2023. Available online: https://iabspain.es/iab-spain-xv-edicion-estudio-redes-sociales/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Tercova, N.; Smahel, D. Digital skills’ role in intended and unintended exposure to harmful online content among European adolescents. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Llovet, C.; Borau-Boira, E.; Martínez-Otón, L. Alfabetización Digital, Redes, Y Fake News: Percepciones Entre Universitarios. Index Comun. 2024, 14, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture. In La cultura de la Convergencia de los Medios de Comunicación; Paidós Comunicación: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J. The Culture of Connectivity. A Critical History of Social Media; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casero-Ripollés, A.; García-Gordillo, M. La influencia del Periodismo en el ecosistema digital. In Cartografía de la Comunicación Postdigital: Medios y Audiencias en la Sociedad de la COVID-19; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M., y Pérez-Escoda, A., Eds.; Aranzadi-Thomson Reuters: Navarra, Spain, 2020; pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Red.es. ONTSI Report. Impact of Increased Internet and Social Network Use on the Mental Health of Youth and Adolescents. Observatorio Nacional de Tecnología y Sociedad. Secretaría de Estado de Digitalización e Inteligencia Artificial. Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital. 2023. Available online: https://www.ontsi.es/es/publicaciones/Impacto-del-uso-de-Internet-y-redes-sociales-salud-mental-jovenes-adolescentes (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Garmendia, M.; Jiménez, E.; Casado, M.Á.; Mascheroni, G. Net Children Go Mobile: Risks and Opportunities in Internet and Mobile Device Use Among Spanish Minors (2010–2015). Red. es/Universidad del País Vasco. 2016. Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=5053 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Sánchez-Burón, A.; Fernández-Martín, M.P. Generation Report 2.0: Teenagers’ Habits in the Use of Social Networks. Comparative Study Between Autonomous Communities. 2010. Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=2824 (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Garitaonandia, C.; Karrera-Xuarros, I.; Jimenez-Iglesias, E.; Larrañaga, N. Menores conectados y riesgos online: Contenidos inadecuados, uso inapropiado de la información y uso excesivo de internet. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lena-Acebo, F.-J.; Pérez-Escoda, A.; García-Ruiz, R.; Fandos-Igado, M. Social media and smartphones as teaching resources: Spanish teacher’s perceptions. Pixel-Bit. Rev. De Medios Y Educ. 2023, 66, 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Martínez-Otón, L.; Ortega-Fernández, E.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M. Social Media as Learning Environments: University Students Perceptions. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), A Coruña, Spain, 19–21 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Churchill, D. The effect of social interaction on learning engagement in a social networking environment. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2012, 22, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, L.; Feller, J.; Nagle, T. Social Media as a Support for Learning in Universities: An Empirical Study of Facebook Groups. J. Decis. Syst. 2016, 25, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

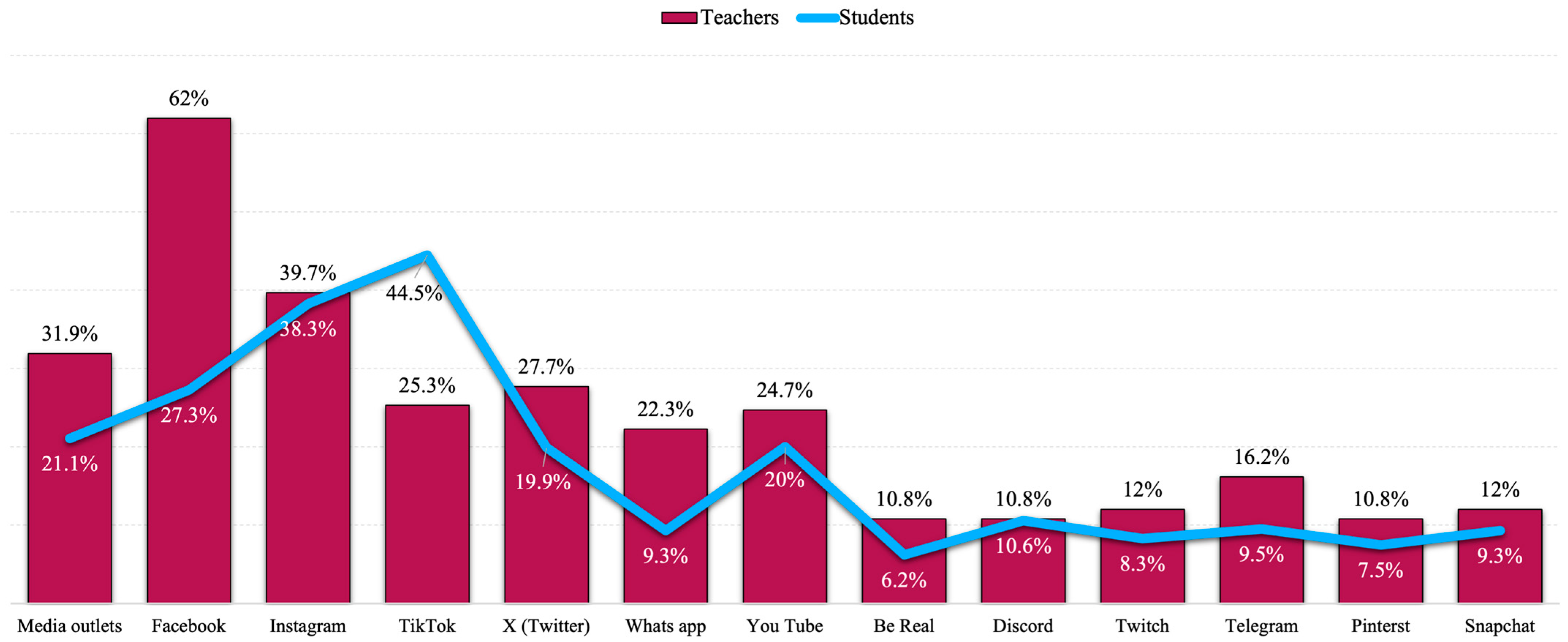

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Ortega Fernández, E.; Martínez Otón, L. Deferential factors in the use of social media among secondary school student and teachers: Challenges for media literacy. AdComunica 2025, 29, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 5th ed.; McGRwHills: Mexico, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reneses, M.; Riberas-Gutiérrez, M.; Bueno-Guerra, N. Who shares fake news? The consumption and distribution of information among adolescents and its relationship to hate speech. Rev. Educ. 2024, 406, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastik, Z. Would you notice if fake news changed your behavior? An experiment on the unconscious effects of disinformation. Comput. Hum. Bahaviour 2021, 116, 106633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, L. Get on the truth train: Faculty perceptions of misinformation and disinformation in the classroom. LOEX Q. 2023, 49, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Melro, A.; Pereira, S. Fake or not fake? Perceptions of undergraduates on (dis) information and critical thinking. Medijske Stud. 2019, 10, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, K.; Voráč, D.; Szotkowski, R.; Krejčí, V.; Mackenzie, K.; Ramos-Navas-Parejo, M. Teachers in a world of information: Detecting false information. Prof. Inf. 2023, 32, e320501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.K.; Griffin, R.A.; Mindrila, D. Teacher perceptions of critical media literacy. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2022, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, T.; Frau-Meigs, D.; Corbu, N.; Santoveña-Casal, S. Teachers’ views on disinformation and media literacy supported by a tool designed for professional fact-checkers: Perspectives from France, Romania, Spain and Sweden. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Teacher’s Perceptions of Fake News and News Literacy. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/1f5c2be796c3793eade3295b8cdc7cd2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Tolentino, J.S.; Brion, R.B. Teachers’ awareness in identifying misinformation and responsible use of social media. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 23, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Diz, P.; Conde-Jiménez, J.; Reyes-de-Cózar, S. Spanish adolescents and fake news: Level of awareness and credibility of information. Cult. Educ. 2021, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeronen, E. Sustainable Education. In Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management; Idowu, S.O., Schmidpeter, R., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Del Baldo, M., Abreu, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3488–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, Z. How to teach students critical thinking skills to combat misinformation online. Monit. Psychol. 2024, 55, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Variable | Items from Questionnaire | Responses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceptions | V1: Creation | Why do you think fake news or disinformation is created? | |||||||

| - By mistake - By malicious intent - Out of boredom | - For fun - For political interests - For economic interests | 1 = Never 2 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes | 4 = Often 5 = Always | ||||||

| V2: Association | What would you associate fake news with? | ||||||||

| - Humour/Entertainment - Information - Distrust | - Manipulation - Gaining popularity | 1 = Never 2 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes | 4 = Often 5 = Always | ||||||

| V3: Distribution | To what extent do you think fake news and/or disinformation is distributed through: | ||||||||

| – TV, press, radio – X (Twitter) – TikTok | – WhatsApp – YouTube – Telegram – BeReal | – Twitch – Discord – Snapchat | 0 = I do not use it 1 = Never 2 = Once | 3 = Sometimes 4 = Often 5 = Always | |||||

| Feelings and practice | V4: Impact in own life | Do you think that fake news and disinformation have a negative impact on your daily life? | 1 = Very unlikely 2 = Unlikely 3 = Neutral | 4 = Likely 5 = Very likely | |||||

| V5: Ability to recognize fake news | How would you rate your ability to spot or recognize fake news and disinformation? | 1 = I cannot recognize them 2 = I rarely recognize them 3 = Sometimes I recognize them 4 = I often recognize them 5 = I always recognize them | |||||||

| V6: Self creation | Have you ever created fake news to share? | 1 = Never 2 = Once 3 = Sometimes | 4 = Often 5 = Always | ||||||

| V7: Sharing | Have you ever shared a fake news story knowing it was fake? | 1 = Never 2 = May be, not conscious | 3 = Sometimes 4 = Often 5 = Always | ||||||

| Knowledge and management | V8: Knowledge | Do you know what fake news and disinformation is? | Yes/No | ||||||

| V9: Fact-checking use | Do you tend to fact-check information shared by friends or family on social media? | 1 = No 2 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes | 4 = Often 5 = Always | ||||||

| V10: Information verification | Do you verify information from multiple sources before believing or sharing it? | 1 = No 2 = Rarely 3 = Sometimes | 4 = Often 5 = Always | ||||||

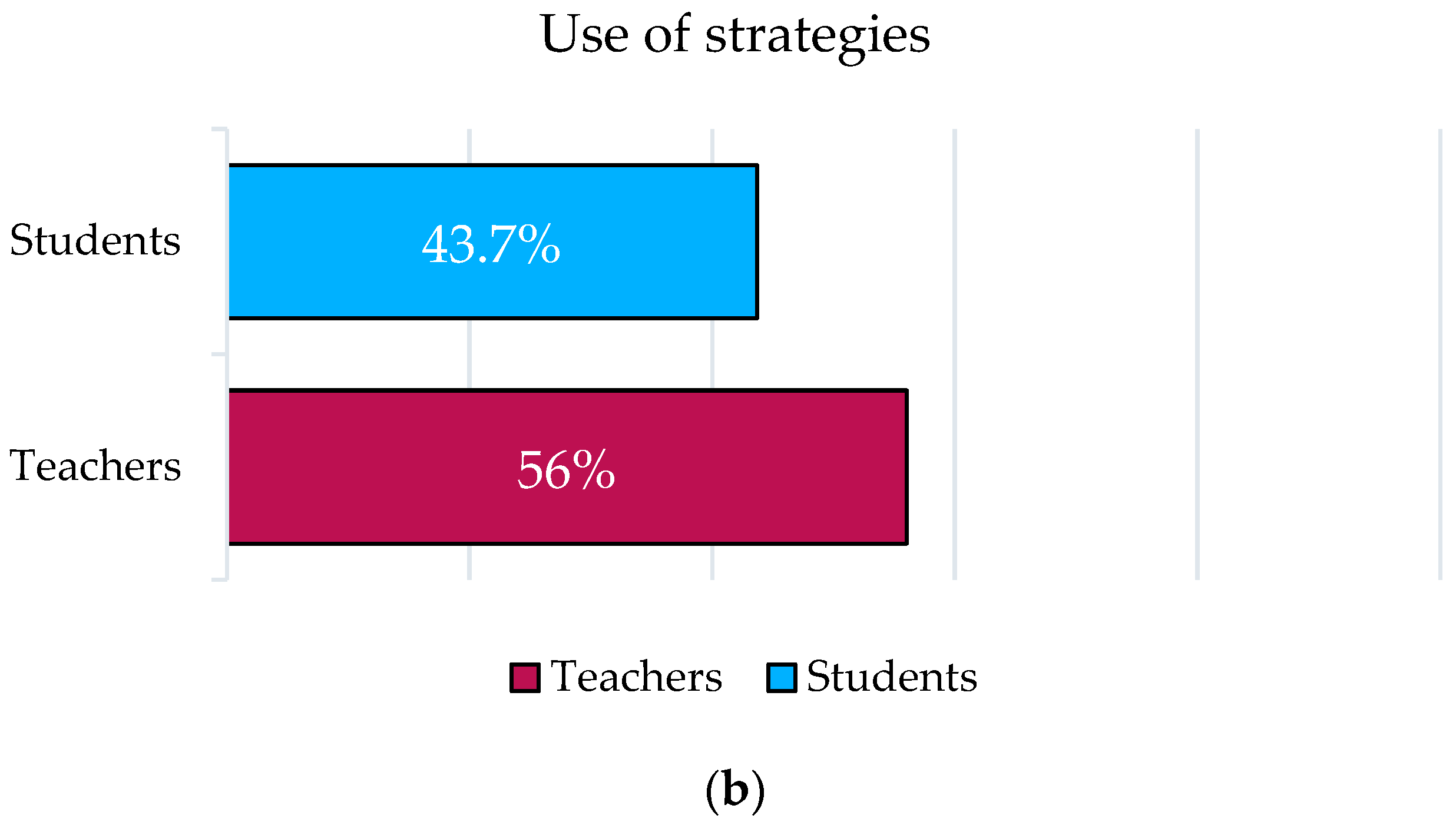

| V11: Management | Do you use strategies or tools to confirm what comes to you? | Yes/No | |||||||

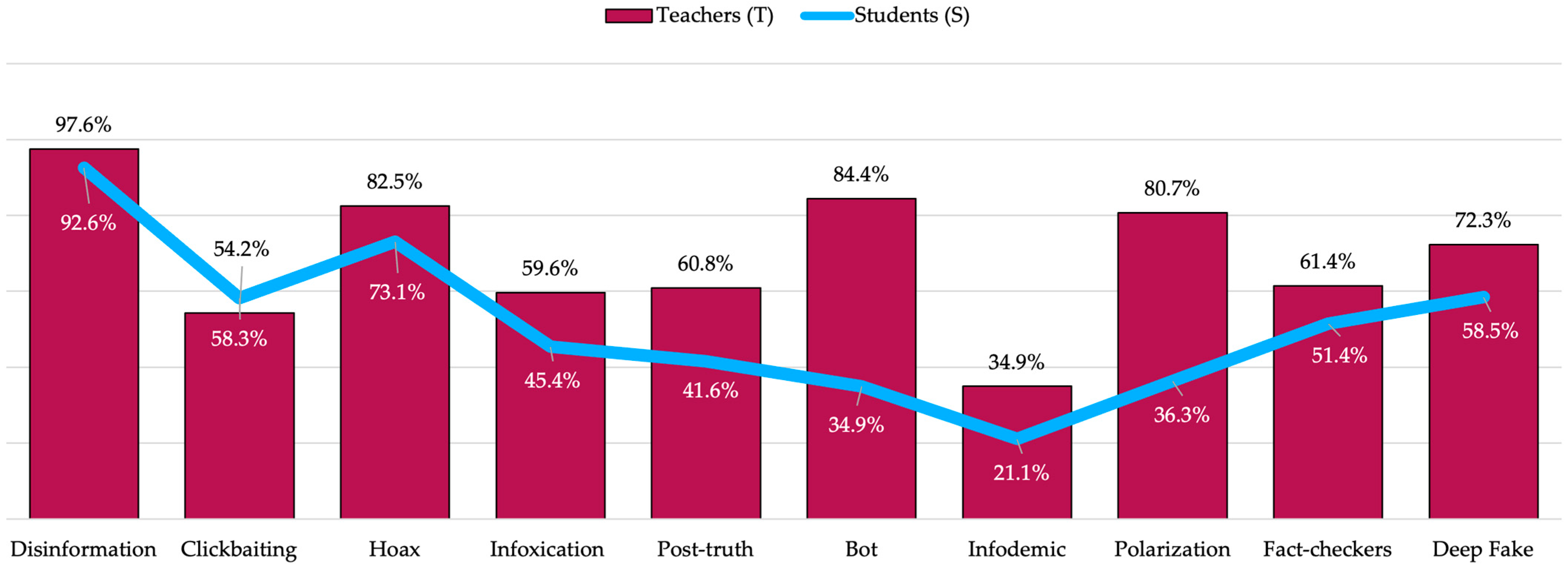

| V12: Recognition | Do you recognize the meaning of any of these words? | ||||||||

| - Fake new - Disinformation - Clickbaiting - Hoax | - Infoxication - Post-truth - Bot - Infodemic | - Polarization - Fact-checkers - Deep Fake | Yes/No | ||||||

| Why Do you Think Fake News or Disinformation is Created? | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | z | p ** | ||

| By mistake | G1 * | 34.1% | 39.9% | 19.1% | 5.3% | 1.7% | 2.236 | 0.025 |

| G2 | 27.1% | 38.6% | 26.5% | 7.2% | 0.6% | |||

| By malicious intent | G1 | 4.6% | 10.6% | 27.5% | 42% | 15.3% | 4.126 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 0% | 4.8% | 24.1% | 49.4% | 21.7% | |||

| Out of boredom | G1 | 9.6% | 17.5% | 31.5% | 32% | 9.4% | −1.935 | 0.053 |

| G2 | 12% | 16.9% | 36.7% | 30.1% | 4.2% | |||

| For fun | G1 | 7.6% | 13.7% | 32.5% | 34.7% | 11.6% | −1.545 | 0.122 |

| G2 | 4.8% | 13.3% | 43.4% | 36.7% | 1.8% | |||

| For political interests | G1 | 6.4% | 12.1% | 25.4% | 37.1% | 19% | 5.886 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 0.6% | 2.4% | 17.5% | 50.6% | 28.9% | |||

| For economic interests | G1 | 5.8% | 13.7% | 29.1% | 33.2% | 18.1% | 6.201 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 1.2% | 1.8% | 19.9% | 50% | 27.1% | |||

| What Would You Associate Fake News with? | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | z | p ** | ||

| Humor/Entertainment | G1 * | 32% | 24% | 26.7% | 12.1% | 5.2% | −1.257 | 0.209 |

| G2 | 38.6% | 16.9% | 34.3% | 7.8% | 2.4% | |||

| Information | G1 | 25.5% | 23.7% | 25% | 16.9% | 8.9% | −0.262 | 0.793 |

| G2 | 37.3% | 11.4% | 16.3% | 22.3% | 12.7% | |||

| Distrust | G1 | 14% | 13.7% | 27.8% | 26.1% | 18.5% | 3.070 | 0.002 |

| G2 | 10.8% | 6% | 26.5% | 32.5% | 24.1% | |||

| Manipulation | G1 | 9.1% | 9.9% | 19.7% | 30.1% | 31.1% | 6.622 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 2.4% | 0.6% | 15.1% | 28.3% | 53.6% | |||

| Gaining popularity | G1 | 11.2% | 9.1% | 21.9% | 29.0% | 28.8% | 1.820 | 0.069 |

| G2 | 6.6% | 2.4% | 21.1% | 44.6% | 25.3% | |||

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | z | p ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fact-checking practice | G1 * | 18.1% | 32.4% | 30.9% | 14.4% | 3.5% | −7.845 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 4.8% | 17.5% | 39.8% | 31.9% | 6.0% | |||

| Information verification | G1 | 14.8% | 25.1% | 38.3% | 14.4% | 7.3% | −7.841 | <0.001 |

| G2 | 6.6% | 12.7% | 30.1% | 22.3% | 28.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Escoda, A.; Carabias-Herrero, M. Practices and Awareness of Disinformation for a Sustainable Education in European Secondary Education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156923

Pérez-Escoda A, Carabias-Herrero M. Practices and Awareness of Disinformation for a Sustainable Education in European Secondary Education. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156923

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Escoda, Ana, and Manuel Carabias-Herrero. 2025. "Practices and Awareness of Disinformation for a Sustainable Education in European Secondary Education" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156923

APA StylePérez-Escoda, A., & Carabias-Herrero, M. (2025). Practices and Awareness of Disinformation for a Sustainable Education in European Secondary Education. Sustainability, 17(15), 6923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156923