Enhancing Cultural Sustainability in Ethnographic Museums: A Multi-Dimensional Visitor Experience Framework Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Ethnographic Museums in Cultural Sustainability

2.2. Visitor Experience and Cultural Sustainability

2.3. The Application of the AHP Method in Cultural Studies

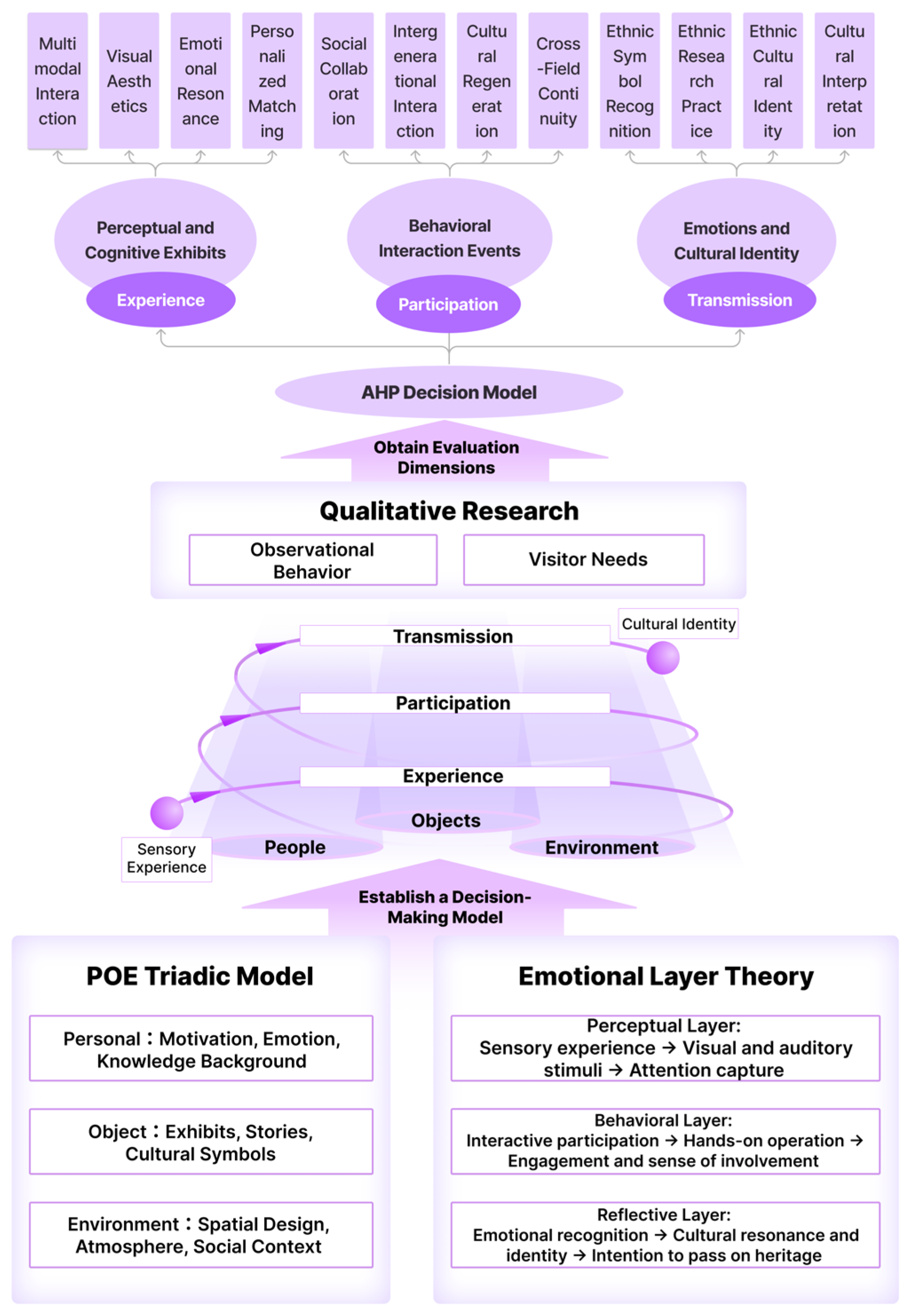

2.4. AHP Judgment Model Explanation and POE Theory

3. Materials and Methods

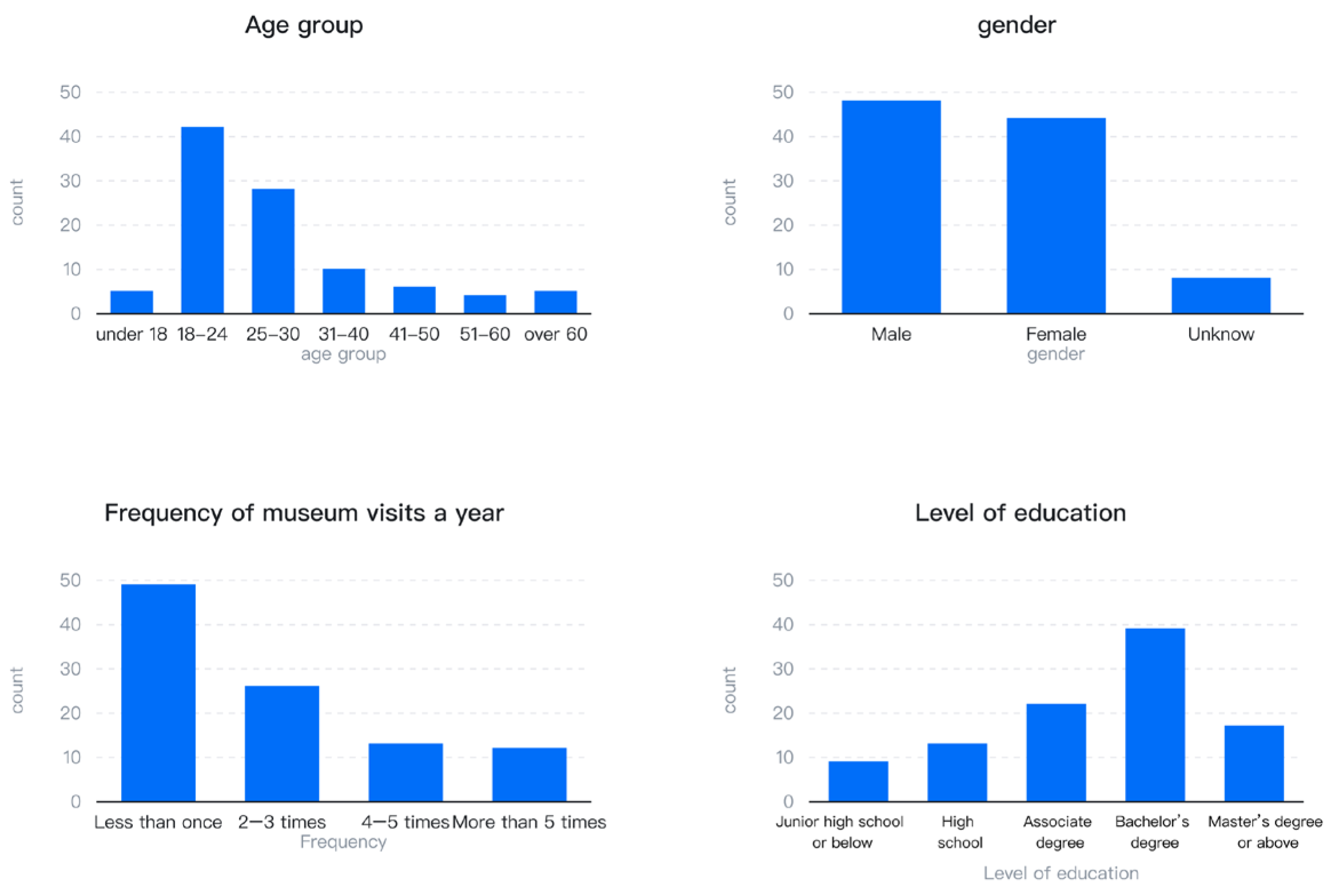

3.1. User Data Collection Objectives and Methods

3.2. Constructing an AHP Hierarchical Model

3.3. Hierarchical Single Ordering and Consistency Test Measurement

4. Results

5. Discussion

Implications and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schou, M.M.; Løvlie, A.S. The Diary of Niels: Affective engagement through tangible interaction with museum artifacts. In Proceedings of the Euro-Mediterranean Conference, Virtual Event, 2–5 November 2020; pp. 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, L.; Aaen, J.E.; Tranberg, A.R.; Kun, P.; Freiberger, M.; Risi, S.; Løvlie, A.S. Algorithmic ways of seeing: Using object detection to facilitate art exploration. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Calvi, L.; Vermeeren, A.P. Digitally enriched museum experiences—What technology can do. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2024, 39, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Lyu, R. Research on a User-Centered Evaluation Model for Audience Experience and Display Narrative of Digital Museums. Electronics 2022, 11, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeeren, A.P.; Law, E.L.-C.; Roto, V.; Obrist, M.; Hoonhout, J.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K. User experience evaluation methods: Current state and development needs. In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic conference on human-computer interaction: Extending boundaries, Reykjavik, Iceland, 16–20 October 2010; pp. 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Gockel, B.; Graf, H.; Pagano, A.; Pescarin, S.; Eriksson, J. VMUXE: An approach to user experience evaluation for virtual museums. In Proceedings of the Design, User Experience, and Usability. Design Philosophy, Methods, and Tools: Second International Conference, DUXU 2013, Held as Part of HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 21–26 July 2013; Proceedings, Part I 2. 2013; pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Walhimer, M. The Museum Experience Gap. Available online: https://www.museumplanner.org/the-museum-experience-gap/ (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Casas, B.; Duval, K.; Lord, N. Evaluating the Evaluators: Investigating Museum Survey and Research Practices. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/investigating-museum-survey-and-research-practices/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Chen, J. Factors Affecting Cultural Transmission in Museum Tourism: An Empirical Study with Mediation Analysis. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241273868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Xie, M.; Guo, Q. How do aesthetics and tourist involvement influence cultural identity in heritage tourism? The mediating role of mental experience. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 990030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.A.; Miao, F.S.; Liu, S. Study on the Impact of Perceived Interpretation Quality on Museum Experience: Based on the Theory of Interaction Ritual Chains and the Application of AR. J. Fudan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 62, 723–740. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, K. Digital Readiness and Innovation in Museums: A Baseline National Survey. Available online: https://knightfoundation.org/reports/digital-readiness-and-innovation-in-museums/ (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Nikolaou, P. Museums and the post-digital: Revisiting challenges in the digital transformation of museums. Heritage 2024, 7, 1784–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekosaari, M.; Pekkola, S. Pushing the Limits beyond Catalogue Raisonnée: Step 1. Identifying digitalization challenges in museums. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 8 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zou, Y.Y. Moments of Experience: A Visitor Study of Red Museum Communication. J. Commun. Rev. 2023, 76, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Q.; Li, Y.; Dong, S.Y. Museum Experience Design Based on Service Design Thinking and Method. Packag. Eng. 2021, 42, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, W. Digital Pathways for Sustainable Development of Museum Pedagogy as Visual Cultural Practices. Comun. Rev. Científica Comun. Educ. 2024, 78, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Y.; Chen, M. Digitalization in Chinese museums: A policy evolution perspective. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2025, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Selim, G. Ecomuseums in China: Challenges and Defects to the Existing Practical Framework. Heritage 2021, 4, 1868–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhong, Y.D.; Li, S.; Tourism, S.O. Evaluation system of forest park tourism resources for pro-poganda sciences based on Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2015, 35, 139–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, D.; van der Veer, G. APEC: A framework for designing experience. In Proceedings of the Spaces, Places Experience in HCI, Rome, Italy, 12–16 September 2005; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik, A.J.; Doering, Z.D.; Karns, D.A. Exploring satisfying experiences in museums. Curator Mus. J. 1999, 42, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qin, J. From digital museuming to on-site visiting: The mediation of cultural identity and perceived value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.Z.; Koo, J.J. The Impact of Online VR Museum Experience Characteristics on Visitor Satisfaction: A Case Study of Chinese Cultural Heritage Museums. Korea Inst. Des. Res. Soc. 2024, 9, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ch’ng, E. Evaluating the management of ethnic minority heritage and the use of digital technologies for learning. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; An, N. The Impact and Application of Virtual Museums from the Perspective of Immersive Experience: A Case Study of the Digital Dunhuang Museum in China. Asia-Pac. J. Converg. Res. Interchange 2023, 10, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrans, B. The future of the other: Changing cultures on display in ethnographic museums. In The Museum Time Machine; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 144–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. The Contemporary Expression of Ethnographic Collections in Ethnographic Museums. Museums 2017, 1, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, S.A. Museums, Diasporas and the Sustainability of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2178–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Jo, Y.; Kang, Y.; Lee, H.K. Interactive experiential model: Insights from shadowing students’ exhibitory footprints. J. Mus. Educ. 2023, 48, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Falco, F.; Vassos, S. Museum Experience Design: A Modern Storytelling Methodology. Des. J. 2017, 20, S3975–S3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, C. Indigenous curation, museums, and intangible cultural heritage. In Intangible Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ringas, C.; Tasiopoulou, E.; Kaplanidi, D.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Zidianakis, E.; Patakos, A.; Patsiouras, N.; Karuzaki, E.; Foukarakis, M.; et al. Traditional Craft Training and Demonstration in Museums. Heritage 2022, 5, 431–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoruso, G. Design for Cultural Cooperation. Interaction, Experience and Heritage Awareness. In Proceedings of the International Congress for Heritage Digital Technologies and Tourism Management-HEDIT2024, Valencia, Spain, 20–21 June 2024; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, P.; Dória, A.; Sousa, M. Interactivity for museums: Designing and comparing sensor-based installations. In Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT 2009: 12th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Uppsala, Sweden, 24–28 August 2009; Proceedings, Part I 12. 2009; pp. 612–615. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museums and Their Visitors, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, B.H.; Bizerra, A.F. Social participation in science museums: A concept under construction. Sci. Educ. 2024, 108, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijnheer, C.L.; Gamble, J.R. Value co-creation at heritage visitor attractions: A case study of Gladstone’s Land. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Conceptualizing the visitor experience: A review of literature and development of a multifaceted model. Visit. Stud. 2016, 19, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, H.; Noble, G. Museums, Health and Well-Being; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Omran, W.; Ramos, R.F.; Casais, B. Virtual reality and augmented reality applications and their effect on tourist engagement: A hybrid review. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2024, 15, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieck, M.C.T.; Jung, T. Value of Augmented Reality to enhance the Visitor Experience: A Case study of Manchester Jewish Museum. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2016, 7. Available online: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/603598/1/Short%20Paper%20AR%20MJM%20Enter%202016.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2016).

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Augmented Reality: Providing a Different Dimension for Museum Visitors. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality (AR and VR), Manchester, UK, 23 February 2018; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Trunfio, M.; Lucia, M.D.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Innovating the cultural heritage museum service model through virtual reality and augmented reality: The effects on the overall visitor experience and satisfaction. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.; Venkadeshwaran, K.; Goyal, U.; Shah, D.B.; Bhushan, B.; Barla, U.K.; Singh, D.P. Enhancing Educational Experiences in Museums through Ethnic Cultural Exhibitions. Evol. Stud. Imaginative Cult. 2024, 8, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake-Hammond, A.; Waite, N. Exhibition design: Bridging the knowledge gap. Des. J. 2010, 13, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Kim, S.; Zhou, T. Staging the ‘authenticity’of intangible heritage from the production perspective: The case of craftsmanship museum cluster in Hangzhou, China. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2015, 13, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, R. A museum in the taiga: Heritage, ethnic tourism and museum-building amongst the Orochen in northeast China. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Min, K. Analyzing the Relevance between the Display of Ethnic Intangible Cultural Heritage and Ethnic Communities: A Case Study of the Suoga Longhorn Miao Community in Guizhou, China. Korea Inst. Des. Res. Soc. 2024, 9, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Cultural communication in museums: A perspective of the visitors experience. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C. Research on narrative design of Shandong Museum. Acad. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, X.; Li, C.; Luo, Q.; Peng, S.; Tang, H.; Tang, R. Renovation of Traditional Residential Buildings in Lijiang Based on AHP-QFD Methodology: A Case Study of the Wenzhi Village. Buildings 2023, 13, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.Y.; Huang, X.L. Research on the Classification of Naxi Traditional Villages in Lijiang Based on the Cultural Heritage Value Evaluation. Sci. Technol. Ind. 2024, 24, 130–135. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.Y. On the Evaluation of Tourism Competitiveness of Ethnic Minority Populated Areas in Yunnan Employing AHP. J. Sichuan High. Inst. Cuis. 2011, 53–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.R.; Yao, Y.G.; Yin, H.G. Study on Evaluation and Optimization Strategy of Tourism Spatial Structure in Qiandongnan Prefecture. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2021, 43, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Models, Methods, Concepts & Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic books: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nigatu, T.F.; Trupp, A.; Teh, P.Y. A Bibliometric Analysis of Museum Visitors’ Experiences Research. Heritage 2024, 7, 5495–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, Z.D. Strangers, guests, or clients? Visitor experiences in museums. In Museum Management and Marketing; Sandell, R., Janes, R.R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M.; Salingaros, N.A.; MacLean, L. A Multimodal Appraisal of Zaha Hadid’s Glasgow Riverside Museum-Criticism, Performance Evaluation, and Habitability. Buildings 2023, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.K.A. In Through the Out Door: Creating the Right Way for a Museum Entry Experience. Ph.D. Thesis, John F. Kennedy University, Pleasant Hill, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Liu, S. Redefinition of Service Design Based on Typology and Psychological Field Theory. Art Des. 2020, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitgood, S. The anatomy of an exhibit. Visit. Behav. 1992, 7, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shangguan, T.M. Application of experience-based multimedia design in museum exhibitions—Take the exhibition of ancient Chinese costume culture. Art Des. 2023, 2, 27–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Research on interactive experiential intangible cultural heritage museum display design. Ind. Des. 2020, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de FSM Russo, R.; Camanho, R.J.P.C.S. Criteria in AHP: A systematic review of literature. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 55, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.; Ariffin, M.; Sapuan, S.; Sulaiman, S. Integrated AHP-TRIZ innovation method for automotive door panel design. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2013, 5, 3158–3167. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario, V.; Petrelli, D.; Nisi, V. Teenage Visitor Experience: Classification of Behavioral Dynamics in Museums. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CSHI), Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cesário, V.; Nisi, V. Designing with teenagers: A teenage perspective on enhancing mobile museum experiences. Int. J. Child-Comput. Interact. 2022, 33, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Jafari, A.; O’Gorman, K. Keeping your audience: Presenting a visitor engagement scale. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Deterding, S.; Kuhn, K.A.; Staneva, A.; Stoyanov, S.; Hides, L. Gamification for health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv. 2016, 6, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilic, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. Progress in Tourism Management: From the geography of tourism to geographies of tourism—A review. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. Current Situation Analysis and Development Strategy Research of Digital Museum in China under the Background of Internet. Oper. Res. Fuzziology 2025, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lan, C. Analysis of the current situation of digital exhibition and interaction in museums. Package Des. 2022, 2, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museum, L. 2023 Lanzhou Museum ‘Our Festival—Mid-Autumn Festival’ ‘Painting Museum—Painting Fans to Talk about Mid-Autumn Festival’ Social Education Activity. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/723462111_121107011?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Stylianou-Lambert, T.; Boukas, N.; Christodoulou-Yerali, M. Museums and cultural sustainability: Stakeholders, forces, and cultural policies. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2014, 20, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture as Source of Sustainable Development and Social Cohesion. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/culture-source-sustainable-development-and-social-cohesion (accessed on 20 July 2014).

| Dimension | Sensory Experience | Interactive Participation | Cultural Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|

| People (Personal Context) | Emotional resonance, interest, motivation, modes of interaction | Visitor communities, social sharing, intergenerational interaction | Cultural identity, learning and creativity |

| Objects (Physical Context) | Exhibit aesthetics, curatorial style, sense of immersion | Interactive devices, digital panels, creative workshops | Cultural symbols, intangible heritage craftsmanship |

| Environment (Social Context) | Spatial atmosphere, exhibition layout and guidance | Offline communities, educational activities, volunteer programs | Cultural dissemination, community collaboration, digital heritage transmission |

| Criteria | Code | Sub-Criteria | People | Objects | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | A1 | Multimodal Interactivity | Visitor engagement with digital devices | AR/VR equipment, tactile exhibits (e.g., bamboo, fabric) | Virtual gallery layout, sensory stimulation from interaction devices |

| A2 | Visual Aesthetics | Visitors’ visual impression of the museum | Aesthetic elements such as ethnic ribbon patterns, phoenix installations, and digital panels | Exhibit and signage design clarity, multilingual navigation system | |

| A3 | Emotional Resonance | Visitors’ emotional response to exhibits | Documentary scripts, interactive theater scripts, endangered language recordings | Immersive AV rooms, emotional ambiance created by lighting and sound | |

| A4 | Personalized Adaptability | Visitor age, interest-based visit pathways | AI recommendation algorithms, adaptive difficulty in interactive modules | Mobile UI adaptability, multi-scene switching logic | |

| Participation | B1 | Community Collaboration | Volunteer coordination skills, visitor collaboration willingness | Collaborative tools (e.g., shared whiteboards, digital task systems) | Offline workshop spaces, online community platforms (WeChat 8.0.61, rednote v8.93, TikTok 35.2.0, Bilibili 8.55.0) |

| B2 | Intergenerational Interaction | Willingness to transfer knowledge, learning motivation of visitors | Cultural knowledge learning kits | Family interaction zones, intergenerational event scheduling | |

| B3 | Cultural Regeneration | Visitor creativity, guidance from culture bearers | Pattern design kits, user-generated content sharing tools | Creation workshops, digital exhibition display zones | |

| B4 | Cross-Context Continuity | Visitor habits in using digital platforms | QR code devices, virtual identity systems | Entry points for online-offline linkage, sustained digital scenario design | |

| Transmission | C1 | Ethnic Symbol Recognition | Visitors’ ability to learn symbols, authority of interpreters | Q&A systems, pattern-matching games | Educational test zones, AI feedback correction interface |

| C2 | Ethnic Study Practices | Learner engagement persistence, willingness to cooperate with communities | Bamboo weaving kits, joint admission tickets | Intangible heritage workshop spaces, She village field visit routes | |

| C3 | Cultural Identity Alignment | Visitors’ sense of belonging, expression on social media | She language learning applets, virtual avatar dress-up modules | Cultural identity questionnaire zones, online community discussion boards | |

| C4 | Intergenerational Cultural Transmission | Youth knowledge articulation, elder digital adaptability | Oral history recording devices, VR teaching tools | Intergenerational task zones, digital skill training corners |

| Comparison Between Factor i and Factor j | Quantitative Value |

|---|---|

| Equally Important | 1 |

| Slightly More Important | 3 |

| Moderately More Important | 5 |

| Strongly More Important | 7 |

| Extremely More Important | 9 |

| Intermediate Values Between Two Adjacent Judgments | 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| Experience | Participation | Transmission | Eigenvector | Weight (%) | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | 1 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 0.491 | 16.378 | |

| Participation | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.617 | 53.896 | 0.005 |

| Transmission | 2 | 1/2 | 1 | 0.892 | 29.726 |

| Main Criteria | Sub-Criteria Code | Judgment Matrix | Eigenvector | Weight (%) | CR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience | A1 | 1 | 2 | 1/3 | 4 | 1.352 | 33.805 | 0.039 |

| A2 | 1/2 | 1 | 1/4 | 3 | 0.651 | 16.275 | ||

| A3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1.702 | 42.547 | ||

| A4 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/5 | 1 | 0.295 | 7.373 | ||

| Participation | B1 | 1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 2 | 0.644 | 16.107 | 0.01 |

| B2 | 2 | 1 | 1/2 | 3 | 1.109 | 27.714 | ||

| B3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1.863 | 46.582 | ||

| B4 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1 | 0.384 | 9.597 | ||

| Transmission | C1 | 1 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 2 | 0.734 | 18.362 | 0.015 |

| C2 | 2 | 1 | 1/2 | 3 | 1.147 | 28.668 | ||

| C3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1.73 | 43.245 | ||

| C4 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1 | 0.389 | 9.724 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruan, C.; Qiu, S.; Yao, H. Enhancing Cultural Sustainability in Ethnographic Museums: A Multi-Dimensional Visitor Experience Framework Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156915

Ruan C, Qiu S, Yao H. Enhancing Cultural Sustainability in Ethnographic Museums: A Multi-Dimensional Visitor Experience Framework Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156915

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuan, Chao, Suhui Qiu, and Hang Yao. 2025. "Enhancing Cultural Sustainability in Ethnographic Museums: A Multi-Dimensional Visitor Experience Framework Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156915

APA StyleRuan, C., Qiu, S., & Yao, H. (2025). Enhancing Cultural Sustainability in Ethnographic Museums: A Multi-Dimensional Visitor Experience Framework Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Sustainability, 17(15), 6915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156915