1. Introduction

Robust, accountable, and transparent governance systems are essential for the long-term protection and resilience of large and complex ecosystems. The governance of complex ecosystems across spatial and institutional scales (i.e., ‘multi-scalar systems’) is sometimes referred to as ‘polycentric governance’, comprising multiple, interdependent decision-making centres [

1] and different governance domains that operate across several nested scales. These complex systems are increasingly disrupted by global challenges such as climate change impacts and political uncertainty, and there are few frameworks available that can monitor and evaluate the health and impact of these systems [

1].

This paper first outlines and then reflects on the stepped methodological process employed to design and implement an evaluative framework to comprehensively analyse and better understand decision-making in large polycentric governance systems [

2,

3,

4]. Given relatively few cases of systemic governance analysis at the wider ecosystem level, we seek to be transparent about our experience. We reflect on the multi-pronged approach we took to engage actors in a process of building a shared language and knowledge base about policy, planning and programme health and reform priorities. We do this to offer a theoretically grounded methodological innovation that the stewards of complex systems might consider when establishing initiatives to assess and improve governance system health. Our objective is to support the stewards of complex ecosystems through a repeatable, deliberative approach that provides opportunities to nudge governance systems towards better outcomes. Our paper is structured as follows. We begin by outlining the most salient aspects of healthy or good governance, which underpins our work. This leads into our methodology, followed by the results arising from its application. We then provide our conclusive remarks and ideas for future use of the methodology developed in this project.

1.1. ‘Healthy’ or ‘Good’ Governance

By ‘governance’ we refer to the structures and processes through which individuals and institutions interact in a complex decision-making system [

5]. This includes a myriad of mechanisms and processes operating at multiple scales that affect the outcomes or consequences of complex environmental decision-making. The ecological and administrative boundaries of multi-scalar contexts are often overlapping or mismatching, while issues of policy fragmentation, siloed approaches to decision-making, limited coordination, and power and knowledge imbalances, hinder the ability of governance systems to flexibly respond to dynamic socio-economic change [

6].

‘Good governance’ or a ‘healthy governance system’ can be characterised by several system attributes such as transparency, accountability, fairness, inclusion, and the effectiveness of decision-making processes to achieve positive societal and sustainability outcomes across multiple domains [

2,

5]. Such system attributes affect governmental, corporate, group and individual policy-making, influencing combined social norms and structures, processes, plans and cultures, and ultimately moderating societal or system outcomes [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Ideally, good governance is underpinned by careful collaborative policy and planning, where success is highly dependent on the social context, collaboration methods and incentive structures [

9,

10]. The social infrastructure underpinning collaborative governance is its ‘social capital’ and is embedded within its relational and normative foundations [

11,

12]. Strong social capital can improve governance systems through inclusive and participatory processes which enable stakeholders and rights holders to reflect and deliberate on environmental challenges [

13,

14]. Deliberation moves beyond merely expanding opportunities for public participation in governance, to providing discursive settings which invite discussion and reflection [

15]. It emphasises reasoned, inclusive, and reflective public discourse as the foundation for legitimate and collective decision-making [

16]. In reference to environmental governance, positive deliberation about system health is also likely to contribute to ecological reflexivity, intended as the capacity of socio-ecological ecosystems to recognise change, reflect on the implications of change and adapt to change through learning [

17].

Establishing good (or healthy) governance across various tenures and jurisdictions is critically important for effectively managing large landscape-scale conservation areas, and should involve state actors, communities, non-government organisations, industries, Indigenous people and others acting together at different scales to equitably address management challenges [

18]. The consideration of management effectiveness has been at the heart of protected area governance for well over a decade [

19] and has been central to GBR governance e since the first GBR Outlook Report in 2009 [

20]. Since 2009, the Reef Authority has prepared a comprehensive Outlook Report every five years. This Report is developed under amendments to the

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975 to provide an assessment of reef health. The Outlook Report is accompanied by an independent assessment of the effectiveness of GBR management [

20], using the IUCN-WCPA framework. This assessment includes consideration of the extent to which conservation goals and objectives are being met, together with an evaluation of how well GBR values are being protected [

21]. Although the assessment is undertaken independently, evidence for each indicator includes information assembled and discussed by GBR management staff with the independent assessors [

18,

19].

Because we sought to involve a much wider range of participants (beyond managers) in the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) process, and because our focus is on exploring the health of wider polycentric and multi-domain governance systems rather than the impact of more specific management actions, we chose to apply a broad Governance Systems Analysis (GSA) approach that was developed specifically for the GBR (See

Section 2.1). The GSA approach has been based on extensive theory development and method testing.

This now globally published, tested and applied methodological approach creates structured opportunities to examine more contextual issues and for diverse theories of change and voices to be heard. We assert that application of the GSA provides deeper insights into management effectiveness within a much broader governance system. Further, reviewed literature suggests that collaborative, deliberative approaches to the assessment of complex governance systems can address challenges in relation to cross-scale partnerships, power asymmetries that hinder equitable participation, and can provide better ways to integrate the diverse knowledges needed for effective governance [

15,

22].

Involving stakeholders and significant rights holders in the M&E of complex ecologically focused governance systems also addresses the need for the development of more public accountability and trust-building; genuine stakeholder and Indigenous engagement; and opportunities for co-ownership of, and commitment to, M&E processes and outcomes [

23,

24]. Heeding diverse voices across various governance jurisdictions from local to global scales can amplify efforts and modify trajectories, as each brings a different perspective to the detection and resolution of potential problems [

25,

26]. Despite this, methods to realise collaborative and deliberative governance in M&E are rare [

1,

27,

28,

29]. As we discuss below, our research seeks to address this gap through an M&E framework underpinned by a collaborative and participatory approach.

The purpose of this paper then is to outline our approach to the analysis and M&E of complex governance systems in some replicable detail. The approach combines reflexive and interactive processes for engaging stakeholders and Indigenous people with the intention of identifying strengths and weaknesses of current governance arrangements. Results from such an inclusive approach can indicate where and how structural and functional shifts are needed to ensure governance goals and objectives are being met. At the same time, it can create opportunities to re-evaluate and modify actions and strategies where needed [

30]. Our approach is rooted in inclusive dialogue and participatory processes involving diverse actors in the GBR and its catchment and, as such, potentially have a deep and meaningful understanding of its governance.

1.2. The Great Barrier Reef Context

The GBR is one of the world’s greatest natural wonders and one of the most awe-inspiring places on Earth. Composed of more than 3000 individual reefs and 900 islands, this incredibly complex ecosystem is home to thousands of species of fish, coral, molluscs, sea turtles, and birds, and supports iconic marine species such as dugongs, manta rays, and whale sharks [

31,

32]. Over 70 Traditional Owner (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) clans share a deep cultural, spiritual, and economic connection to the GBR, going back in time over thousands of years [

29]. Major industries such as tourism, agriculture, and fisheries are supported by the GBR, making it a significant economic asset and a much-treasured social and cultural icon [

33].

The GBR was World Heritage listed in 1981 in recognition of its Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) as one of the most remarkable places on earth [

34]. Australia has a duty under the World Heritage Convention to ‘identify, protect, and conserve’ the GBR’s OUV [

35]. Such duty is of paramount importance especially as the GBR is facing severe, multiple, and interconnected threats to its resilience and survival. These are primarily due to anthropogenic climate change impacts, but also those related to deteriorating water quality, dredging, coastal development, impacts of industries, inconsistent governance and enforcement issues [

33,

36].

Governance of the GBR is complex, as it comprises many government and non-government entities, all operating at various spatial and temporal scales, each with their own goals and objectives that variously work together to achieve mutual outcomes. Sometimes the consequences of decision-making within one part of the governance sub-system (e.g., a specific governance domain such as fisheries management) influences the outcomes of another, especially where priorities differ. For example, the failure of one component (e.g., restoration of riparian vegetation) to deliver its intended outcomes (e.g., healthy coastal ecosystems) needs to be understood within the broader GBR governance system context (e.g., development pressures in the catchment) [

37].

One important domain within the GBR governance system relates to the Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan (the Reef 2050 Plan), which was jointly released by the Australian and Queensland governments in March 2015 [

38]. The Reef 2050 Plan was created to address key threats identified through the GBR Strategic Assessment Report 2013 and the GBR Coastal Zone Strategic Assessment Report 2013 [

18]. The Reef 2050 Plan was designed to be a living document, and, to date,, has undergone two formal reviews since its first release. The Reef 2050 Plan is Australia’s overarching integrative framework aimed at protecting the GBR’s OUV and improving its resilience through several goals and objectives focused on GBR health, including its governance [

39]. The Plan directly stresses the importance of governance, with a major Plan objective being that ‘governance systems

are inclusive,

coherent, and

adaptive’ [

39].

To be

inclusive implies that all relevant stakeholders, rights holders and Traditional Owners should be part of the decision-making processes related to GBR management. Although a long-held aspiration for many Traditional Owners, inclusivity in decision-making is a relatively recent development [

40]. To facilitate effective responses to actions and objectives outlined in the Reef 2050 Plan, an independent Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Steering Group developed a Traditional Owner-led Implementation Plan. This complimentary plan has enabled a more inclusive approach to Traditional Owner-led vision building; one in stark contrast to the usual government-led decision-making approach [

41]. A GBR Traditional Owner Taskforce has since been established to provide a strong and representative voice to achieve Traditional Owner aspirations for the Reef, capacity-building through and within the Implementation Plan, and coordination of monitoring and evaluation of Plan actions [

40].

To avoid conflict or the repetition of efforts, promote alignment of policies and regulations and encourage cross-sectoral collaboration between GBR actors, the wider GBR governance system fundamentally needs to be

coherent. As such, a multi-tiered approach to GBR management is crucially important to enable diverse actors at multiple scales opportunities to collaborate and influence each other in collective management endeavours [

37]. Governance systems must also be

adaptive to the dynamic and constantly changing environmental and socio-economic conditions impacting the GBR. Adaptability allows for flexibility in management approaches and for adjustments and redress where issues arise. For example, in relation to prioritising adaptive approaches in the governance of the GBR, McHugh et al. [

42] have previously suggested adopting a ‘reflexive governance’ approach; one focussed on governance structures being responsive and inclusive to improve the effectiveness of efforts aimed addressing climate challenges.

Although governance system health is a critically important component of the Reef 2050 Plan, the active assessment and monitoring of system governance remains ad hoc. This is despite governance being identified as a critical monitoring gap [

43] and, as such, an investment priority by the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program (RIMReP). RIMReP was established to track progress against the Reef 2050 Plan goals and objectives [

44]. Resolving this gap is crucial for achieving resilience and conservation outcomes for the GBR, due to the multi-level, polycentric system of governance integrating global, national, state, and local actors, along with Indigenous groups and other rights holders, multiple stakeholders, scientific and government bodies, industry, and communities [

44].

1.3. Complexities and Challenges of GBR Governance

Within the context of the GBR and its catchment, there are many occasions where key actors such as industry, community groups, government agencies, land holders and Traditional Owners cooperate to achieve shared goals [

35]. On occasions, however, the multiple actors involved have different priorities and objectives, sometimes resulting in different (and potentially negative) consequences for different parties [

45].

The GBR governance system is characterised by inconsistencies in policy development, implementation and enforcement across multiple system domains. This is due to the interconnected and often overlapping responsibilities of diverse actors and institutions [

46]. These actors involve state, regional, and local governments, in addition to Indigenous institutions, industries, and non-governmental organisations such as conservation groups. Such multi-layered context is often affected by issues of fragmentation which often leads to conflicting policies and inefficiencies [

47]. Such issues include, for example, variable enforcement standards, resource constraints, and differing accountability mechanisms. These issues are equally embedded within the overarching impacts of anthropogenic climate change, from coral bleaching to extreme weather events, which increase the urgency for adaptive approaches to governance monitoring even further [

48].

The Reef 2050 Plan recognises and aims to integrate and resolve these issues. However, policy responses are often fragmented and disconnected from long-term outcomes, especially where interested parties are siloed, preventing collaboration [

47,

49]. In turn, a lack of a dedicated and long-term governance monitoring system to address progress of the Reef 2050 Plan further constrains optimal governance [

4].

Assessment and monitoring of the Reef 2050 Plan’s governance system creates a systematic approach that can clearly pinpoint aspects of governance that are progressing well, as well as highlighting areas for improvement. The health of the Reef 2050 Plan governance system refers to how well the policies, programmes, instruments and other activities involved with GBR management interact and impact on key outcomes for delivery through the Plan. In our view, the Reef 2050 Plan governance system would be considered ‘healthy’ through the achievement of intended outcomes across different spatial and temporal scales.

2. Methodology

This project’s action-based methodology was epistemologically framed by post-positivism [

50] and practically framed by deliberative action, appreciative inquiry and a highly collaborative approach. This was achieved through a multi-method programme of research over three years (2022–2024), as characterised in

Figure 1 below.

In alignment with the participatory ethos of this research design, the appreciative inquiry approach provided a constructive framing to the investigation, encouraging collective problem-solving and resulting in the development of a shared vision [

51]. The project benefitted from the contributions of members of the existing Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Steering Group. The overall work was also guided by an independently chaired Project Steering Committee and a Project Technical Working Group. The Project Steering Committee comprised fifteen individuals including the independent chair; one person from Griffith University; staff from state and Commonwealth marine park management agencies; and staff from the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. The Committee met regularly to provide strategic advice and review project progress. There were three Technical Working Group members drawn from State and Commonwealth agencies who supported the research team in developing the monitoring framework [

4].

The assessment was the culmination of analysis of data from the literature; practice case studies; two rounds of in-depth interviews and several focus group discussions with key informants including Traditional Owners. The analysis was also informed by Technical Working Group and Steering Committee review [

4]. Specific steps are presented here in two major phases: (1) developing the framework (achieved through reviewed literature; GBR governance network mapping; analysis of key actor interviews and focus group discussions; Technical Working Group and Steering Committee inputs; applying a theory of change; finalising the framework); and (2) applying the framework (secured through the application of multiple lines of evidence; data assessment; data visualisation and reporting) to benchmark the Reef 2050 Plan governance system [

4].

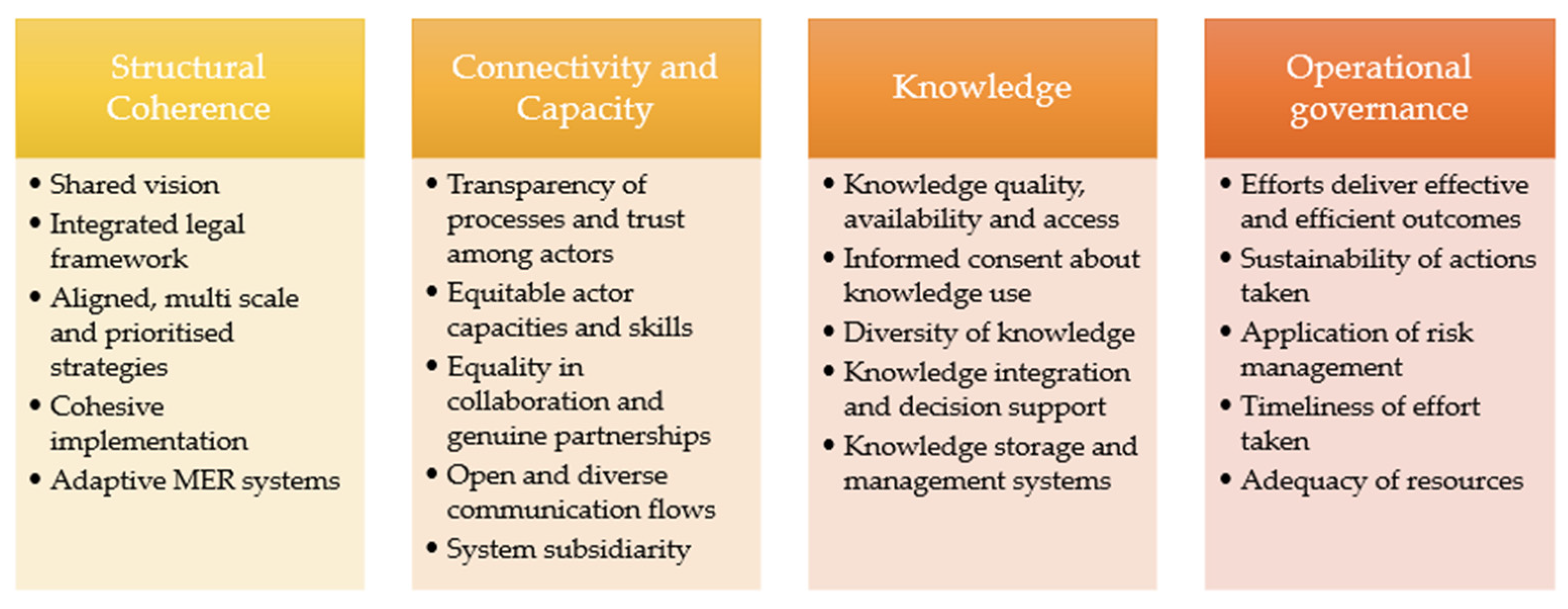

2.1. Developing the Framework

The framework was developed in a number of stages (i.e., literature review, key actor interviews, network mapping and focus group discussions). It builds on the GSA method to systematically assess risk management in large, polycentric governance systems to support system improvement [

52]. This theoretically informed and empirically tested method is generally used to analyse the many components of complex governance systems, applying theoretically sound evaluative criteria with the aim to support continuous improvement in such systems. Initially developed and trialled in the GBR between 2012 and 2016, the GSA approach has previously been used experimentally to identify and analyse the multiple governance domains contributing to the overall health of the GBR governance system [

45]. Although developed with the GBR in mind, the GSA has since been applied internationally; for example, in relation to analysing the governance of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Japan and Indonesia by Morita et al. [

53]. In our case, GSA was selected as (i) it had been specifically developed and trialled over several years within the GBR context; (ii) our literature review continued to point to GSA as being the most robust approach available for the deliberative analysis of complex governance systems.

2.1.1. Literature Review

Between February and March 2023, we reviewed a broad range of literature to provide a global overview of monitoring and evaluation frameworks relevant to the assessment of complex reef governance systems. Our focus was the identification of key characteristics (attributes) grouped thematically into four clusters of attributes that could describe and monitor the governance system associated with the development, delivery and review of the Reef 2050 Plan [

4]. Results of this review revealed that:

The assessment and monitoring of governance health (at a range of scales) is of global interest;

Application of a robust governance monitoring system is critical to ensure that Reef 2050 Plan outcomes are achieved in ways that benefit the GBR and all of its ecological, social, cultural and economic values.

Academic and grey literature were further reviewed to explore dimensions of each attribute. This included the exploration of formal reports and policy documents related to the Reef 2050 Plan governance system. Vella et al. [

4] provides in-depth detail of this reviewed literature.

2.1.2. Key Actor Interviews to Inform Framework Design

Twenty-one key informants were interviewed to learn from their perspectives about what was important to include in a governance monitoring framework for the Reef 2050 Plan. Interviewees were specifically targeted based on their experience and expertise in contributing to the development and implementation of the Reef 2050 Plan, and included peak body and industry representatives, government and non-government organisations, researchers, and seven Traditional Owner members of the Reef 2050 Reef Traditional Owner Steering Group. Interview analysis highlighted many similarities found in the reviewed literature, including:

The fact that multiple benefits could be accrued from building a collective understanding of complex governance systems such as those underpinning the Reef 2050 Plan, including the development of shared participation in, and responsibility for continuous improvement of the system;

The possibility that many whole-of-system benefits could be gained from the application of a monitoring framework to evaluate complex, interconnected governance systems;

That there was value in identifying system attributes which could be used to create the scaffolding needed for the development of the monitoring framework.

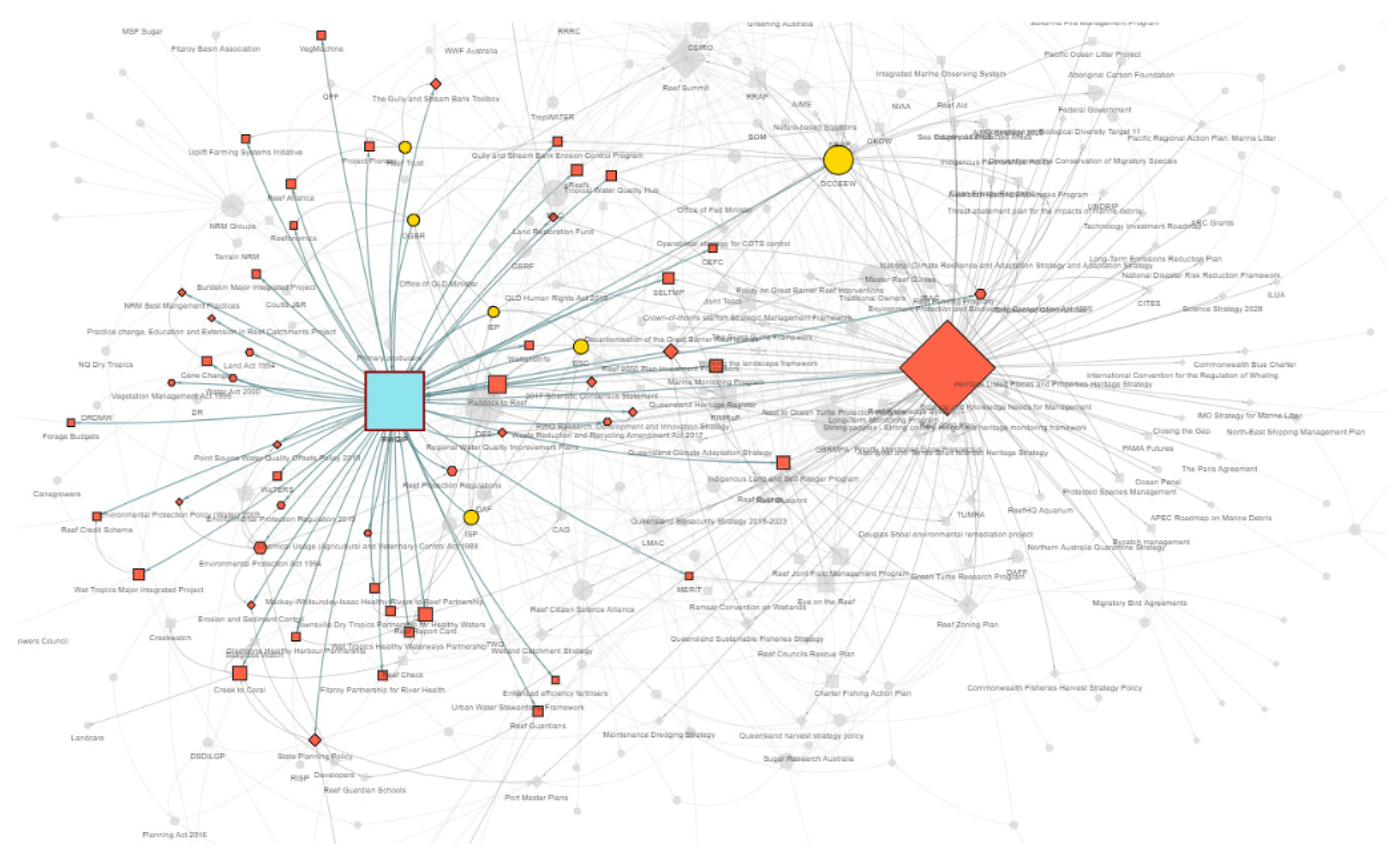

2.1.3. Reef Governance Network Mapping

More than 300 interconnected, nested and layered instruments (e.g., funding programmes, legislative actions, policies, formal partnerships) affecting action within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system were identified through systematic mapping of GBR actors (e.g., land managers, universities, industry), institutions and regulatory arrangements. The project team used the igraph and visNetwork software packages in the ‘R’ programming language for this purpose, based on functionality and accessibility. (R is open source and scripts are saved in text-based formats.) (See

Figure 2 below). These maps helped the team and other actors explore and better understand governance connectivity and linkages underpinning the Reef 2050 Plan governance system [

50].

2.1.4. Focus Groups to Refine Framework Design

To optimise inclusive collaboration, targeted actors with a wealth of GBR knowledge and experience were approached from a wide range of institutions and groups (peak bodies, industry, researchers, etc.) to participate in in-depth focus group discussions about the emerging framework. Detailed contributions from a wide cross-section of GBR Traditional Owners were also obtained through the Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Steering Group.

To ensure the framework developed was robust, we developed a Stakeholder Engagement Plan to support both the previously mentioned and targeted one-on-one interviews and the focus groups with experienced GBR actors. The first round of interviews, conducted with twenty-one participants, focused on interviewees’ experience in developing and implementing the Reef 2050 Plan. Perceptions of the Reef 2050 Plan governance system were also visualised through a mapping exercise to identify how different actors viewed various elements of the system. Next, the focus groups in Brisbane and Cairns (sixteen participants) gathered GBR expert perspectives on the monitoring framework being developed by the project team.

2.1.5. Application of a Theory of Change

We applied ‘theory of change’ thinking to illustrate how and why a desired change may occur through governance improvement. This process helped us to articulate underlying assumptions associated with possible chains of events (causal links and consequences) arising from potential actions that could be applied to system improvement [

54]. We began by articulating the context for multi-scale decision-making processes within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system [

55]. We next considered both the strategic cohesion and connectivity within the system, and how knowledge is transmitted to make decisions. We also considered how to effectively use diverse knowledge sets (including the incorporation of Traditional Owner views) for mutual outcomes, as well as the capacity of the system to implement effective action. Finally, we incorporated the use of targeted monitoring, evaluation, and learning processes into the theory of change process [

56]. These steps reinforced the need for clarity about assumptions and the willingness of all actors to learn in order to focus on specific elements of transformation and change within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system [

55,

57]. It enabled us to gain an overall perspective of potential impacts and outcomes through considering ‘if’ things were to change, ‘then’ what would happen, leading to ‘impact’. This allowed us to then consider how various system improvements could contribute to more ‘transformation and change’.

2.1.6. Finalising the Framework

Results from the literature review, governance mapping, and the first round of in-depth interviews, together with advice and guidance from the focus groups, the Steering Committee and Technical Working Group, provided the structure for a preliminary monitoring framework. The results of all of these integrated processes helped us to finalise the clusters and associated attributes. Appreciative inquiry approaches guided the process, which enabled us to focus on strengths rather than deficits of the governance system [

58]. As a more specific methodological note, it should be mentioned that, in the development of the framework, all interviews were recorded for analysis upon obtaining consent from participants. The first round of interviews were summarised in interview notes, which were then coded and analysed using NVivo12 to identify and interpret patterns and divergences in data [

59].

In summary, the key steps leading to the development and refinement of the governance systems attribute and cluster framework are outlined in

Figure 3.

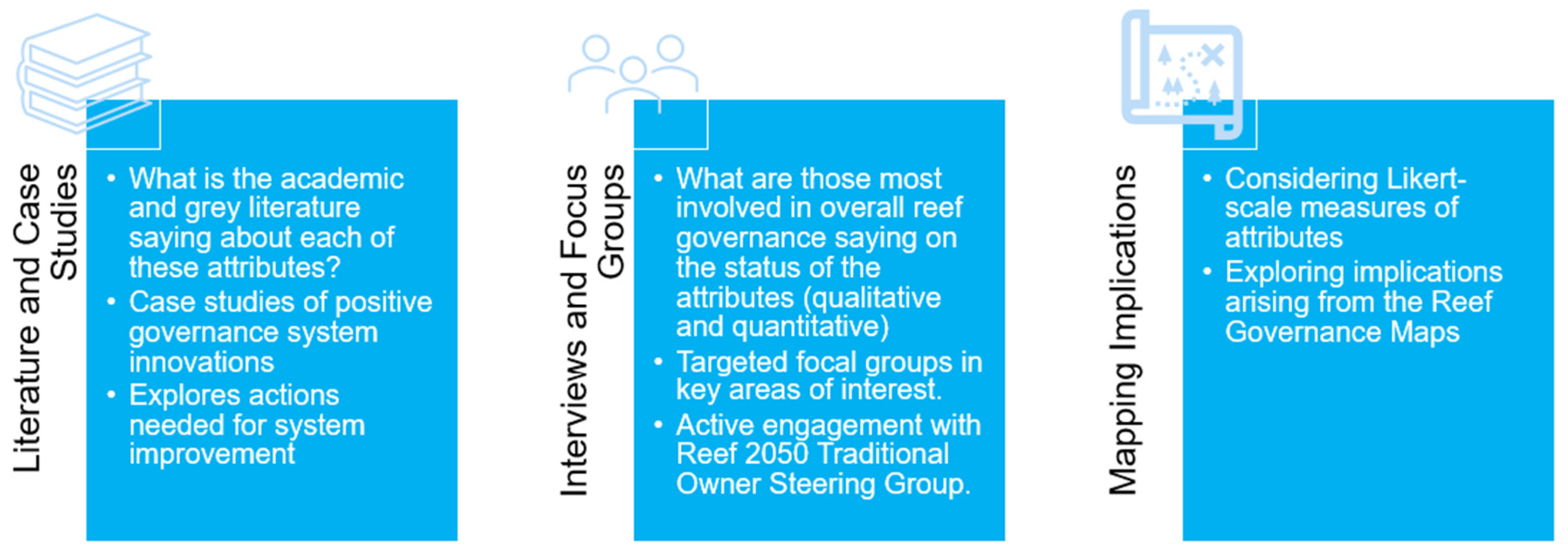

2.2. Populating the Framework Using Multiple Lines of Evidence

To populate the data needed for qualitative assessment of each of our identified governance system attributes, we explored a wide range of data and evidence derived from multiple sources as shown in

Figure 4 below. Initially, international and Australian academic literature together with GBR-focused reports, policies, and consultancy documents were scanned. For each attribute, we also described a GBR-related case study to illustrate its importance within the context of the Reef 2050 Plan governance system. We then again invited deliberation of each attribute with GBR experts through twenty in-depth interviews; three focus group discussions; and through the Steering Group and Technical Working group. As part of this process, conversations were again held with members of the Reef Traditional Owners Steering Committee. In relation to the interviews, participants were selected for their broad experience of Reef 2050 Plan. Interviewees were drawn from Australian and Queensland Governments, research institutions, non-governmental organisations, and consultants from a range of service delivery providers. Commonly, these mature and experienced officers had held relevant roles across several different types of organisations.

During the interviews participants used a Likert scale to rate each attribute (from healthy to unhealthy) and provided narratives to support their scores. Focus group participants were invited to review a draft consolidated evaluation derived from interviews, case studies and reviewed literature, and to discuss findings of the benchmark. For the second round of interviews we recorded scores (for each attribute of the monitoring framework) and narrative data. De-identified scores and narratives were tabulated in a spreadsheet. Scores were summarised using basic statistical functions and plots; narrative data was analysed through a manual coding system to identify the main messages from the interview narratives. Methodological reflections were also recorded. A similar analytical approach was adopted in relation to focus group workshop data. In this case, the notes from two researchers attending the workshops were combined and summarised to gather key insights and information from the workshop participants

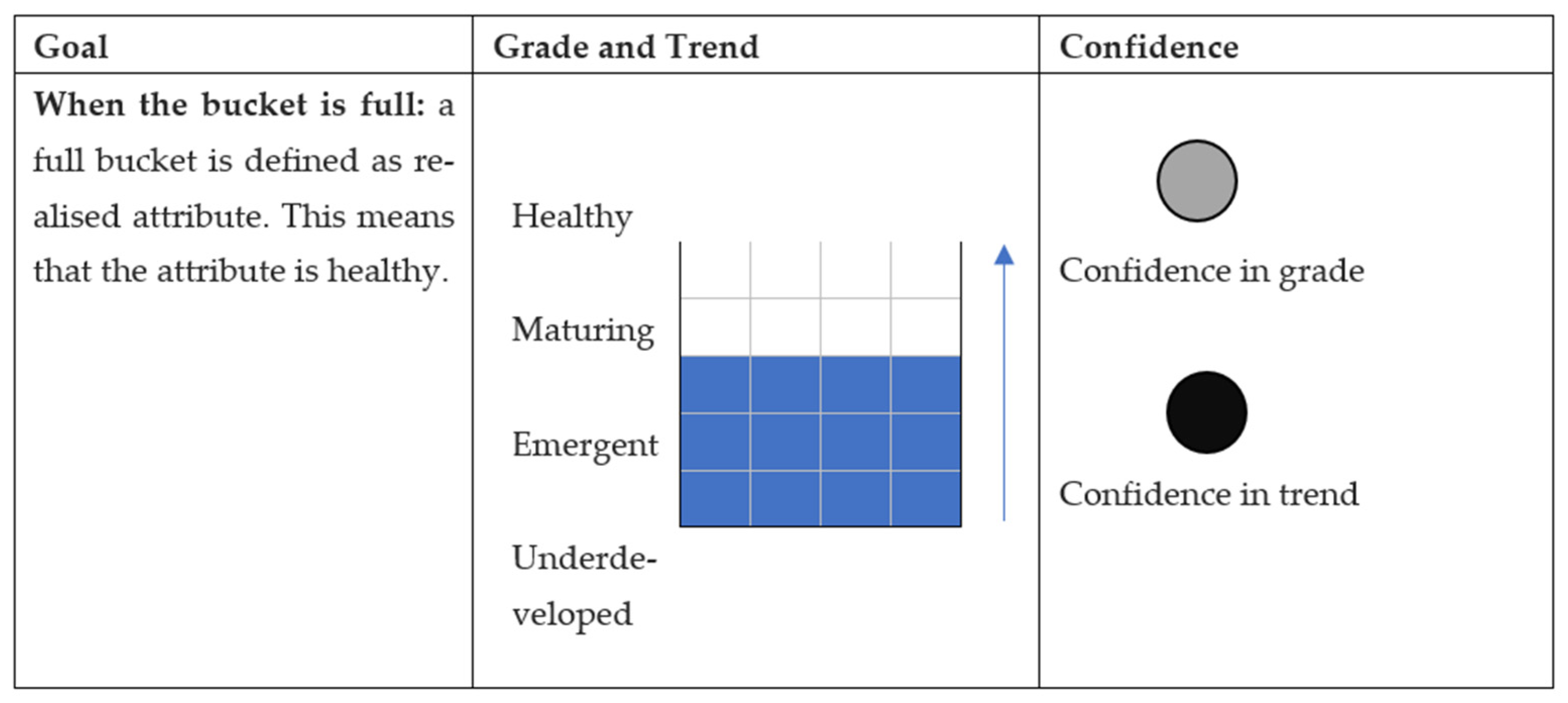

2.3. Data Visualisation and Reporting

The topic of data visualisation and reporting generated considerable conversations among Steering Committee and Technical Working group members. These discussions confirmed that a rich text-based, qualitative assessment was a useful outcome, although they also acknowledged that it was important to describe and communicate relationships between attributes, and to provide a visual representation of the strength of each attribute. Discussions also indicated that this style of reporting enables: (a) results to reach a broad audience; (b) rapid interpretation of findings in briefing notes and summary documents; and (c) provides trend data by comparing attributes over time.

4. Discussion

Improving governance has the potential to resolve a myriad of issues in large-scale, social-ecological systems [

60] and ideally involves a variety of actors participating in decision-making across different jurisdictions and spatial scales [

18]. Opportunities for reflexivity through inclusive deliberation enables the governance of social-ecological systems to respond to reflection on its performance [

17]. In Australia, as van Bommel [

6] noted, collaborative approaches to governance system improvement are emerging but are not yet routinely embedded in research, perhaps due to challenges such as institutional barriers, issues with coordinating between multiple parties, and managing differing expectations [

61]. Collaborative approaches to long term monitoring and evaluation of governance systems are even rarer [

1]. Our research stands as an exception to this reality, as it is based on the development of a highly participatory research design to ensure that perspectives and knowledges of diverse groups were captured and integrated throughout all stages of the research process. We believe that deep, multi-actor participation in M&E of large polycentric governance systems provides all actors with a safe space to start a conversation about improving governance, and in doing so, moves the whole system towards a more deliberative and adaptive governance model. By deliberative governance we mean that opportunities exist for diverse individuals, groups, agencies, industries, rights holders and other actors to come together to discuss, reflect upon and act on pressing issues at play within the governance system [

13].

Within the GBR Marine Park, numerous advisory groups, committees and agreements, each focusing on a particular GBR issue or location, are already well established and have been functioning extremely well for several decades [

62]. However, there has yet to be a comprehensive deliberative process for assessing the wider effectiveness of the whole GBR governance system. As such, we believe that this paper makes significant methodological contributions to the concept of improving deliberative governance, by using inclusive and collaborative M&E processes for the assessment of a large polycentric governance system. We have borrowed from deliberative and collaborative research and practice approaches to develop a framework to monitor the governance health of the GBR Reef 2050 Plan, a complex and dynamic ecosystem where networks of interactions are managed through numerous agencies for different purposes (e.g., conservation, fisheries, tourism, traditional use), sometimes resulting in conflicting outcomes.

In particular, we focused on monitoring and reporting on the health of the governance system underpinning the Reef 2050 Plan to illustrate the progression of its objectives and goals. A comprehensive literature review investigated the global context of governance monitoring and evaluation, with implications for the GBR. Concurrently, to start shaping the form of the GBR governance monitoring framework, we gathered insights through interviews and focus group discussions with GBR governance experts and Traditional Owners. We next created a network map of GBR governance; and developed a clear theory of change to identify transformative pathways for a robust governance system. We then invited participants to visualise their understandings of the GBR governance system through an interactive mapping exercise to highlight the interconnections between key actors and policies.

Underpinning these activities was a collaborative philosophy emphasising inclusive, communicative, and participatory processes to solve complex problems and foster informed decision-making [

63]. Finally, we benchmarked the framework by exploring multiple lines of evidence, which included a second round of interviews, and a series of focus groups framed within an appreciative inquiry approach; in addition to the development of a result-based visualisation tool based on a ‘bucket’ concept to illustrate our results. This evaluative approach is independent of, but now well embedded within, the existing Reef 2050 Plan governance system, ensuring high levels of transparency and trust among all GBR actors.

Over the course of our research, we encountered a series of limitations, due to the nature of our research work. For example, we found that at times conversations about some aspects of governance were contentious, especially when broaching sensitive topics. We also found that some of our key informants, despite having a long involvement in GBR management, found it difficult to visualise various relationships and networks associated with different elements of GBR governance which they may not be familiar with. Indeed, some had quite a narrow view of ‘governance’ and of the wider system and were more likely to associate the term governance solely with specific institutional policies, plans strategies and procedures. The focus of our research, on the other hand, was to establish how well GBR actors were working together in implementing formal and informal instruments and activities within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system. We found one of the biggest challenges was indeed the need to build the capacity of, and communication across, many diverse system actors to develop a shared language about complex governance systems.

To resolve this issue, and to approach the topic of governance in more accessible terms, we were initially advised to refrain entirely from using the term ‘governance’ and use the term ‘collective capacity’ instead. However, as our first round of interviews revealed, the alternative terms suggested by management agencies like ‘collective capacity’ was not theoretically accurate and also could be somewhat confusing to key actors with long standing knowledge of governance issues. So, following deliberated advice from the GBR governance experts on the project’s Steering Committee, it was later agreed to consistently use the term ‘governance’ as it was more comprehensively suited to the focus of our analysis. Perhaps more importantly, the shared conversation about governance itself served to build a deep collective understanding of its meaning and importance.

Another limitation was in relation to how to measure governance system health, as previously developed rating scales and qualitative data were considered not appropriate in the context of our project. This was due to several reasons, for example, the potential for politically sensitive issues to arise when using ‘traffic light’ scoring/ranking systems, or difficulties in representing trends over time in the case of purely using qualitative data [

64]. After reviewing several options, and consulting with the Technical Working Group and the Steering Committee, it was decided to combine qualitative and quantitative analysis descriptors through an appreciative inquiry approach and a more positive language for representing scores with the concept of ‘buckets’ representing attribute grades. Mitigating the limitations, a crucial support system was provided by the project Steering Committee, with its independent Chair, and the Technical Working Group.

5. Conclusions

Robust deliberative approaches to analysing and reporting on large-scale, complex polycentric governance systems are rare. Our approach provides a clear pathway to develop and implement an approach to governance system evaluation that facilitates dialogue about the health of specific governance attributes, and which can be repeated consistently at regular intervals to show trends over time, even if a completely new team of assessors was to be appointed. To maintain this reliable and inclusive approach, we recommend that a regular benchmark and progress report be completed every two-to-three years, in line with key GBR reporting cycles. Importantly, the research team, the Reef 2050 Plan Executive Steering Committee (senior executives from state and Commonwealth government agencies with jurisdictional responsibility for the GBR), and other key GBR actors should continue to work together to co-design responses to the key governance systems weaknesses identified.

Although developed for the GBR, we believe our methodology is both cost-effective and adaptable to other governance systems globally. We demonstrated that our approach provided a safe place for diverse actors to reflect on multiple lines of evidence, develop a shared language and articulate value judgements on a range of topics pertaining to polycentric governance. Inspired by the international application of the GSA from which this work is adapted, e.g., Morita, Okitasari and Masuda [

53], and having successfully completed the first benchmark of our monitoring framework, we suggest that the latter can be applicable to assess the governance health of complex ecosystems well beyond the GBR.