Abstract

In the 2021 summit, ASEAN leaders acknowledged the ocean as an essential driver of economic recovery post pandemic, leading to the ASEAN Declaration on the Blue Economy for the responsible management of marine resources. As an ASEAN nation with a long history in the fishing sector, Indonesia then actively spread this concept across the region. The hegemony theory of Gramsci, which considers the interaction of a nation’s material resources, ideational influence, and institutional strategy, is further used to assess Indonesia’s leadership dynamics in the ASEAN to obtain consensus-based power. In this study, Joko Widodo’s speeches from 2023 are taken out and coded to determine the narrative that Indonesia constantly reinforces. With thematic analysis, speech data is processed to generate keywords such as unity, cooperation, and shared responsibilities, which Indonesia often uses to advance its regional agenda. By aligning member states’ interests with regional goals, Indonesian governance creates common ground for a blue economy and emphasizes how the sea is an integral source of opportunity for the region’s position as the Epicentrum Of Growth. Instead of pushing countries to agree with directives, Indonesia effectively advocates for regional agreements and ASEAN-led structures through the blue economy framework, with the ABEF emerging at its 2023 ASEAN chairmanship deliberations.

1. Introduction

For many years now, Indonesia has been recognized as an archipelagic nation gifted with plenty of resources from nature. According to the National Marine Reference Data, which were released in 2018, Indonesia has a marine water area of 640,000,000 hectares, as its territory is geographically encircled by waterways and oceans. The oceans provide vitality to the world’s ecosystems that keep the world habitable for mankind to live in, and it has vast resources as well as the ability to foster growth in the economy. The way we regulate and utilize resources is critical to humanity’s existence and limiting global issues in the coming decades. However, the oceans continue to be threatened, and it is most likely due to widespread fish exploitation, acidifying oceans, and marine debris. As a result, taking advantage of the ocean’s entire potential has been recognized as crucial for long-term economic growth and wellbeing [1]. In taking advantage of this, one of the ways Indonesia takes advantage of is the production of fishing. For instance, in 2022, Indonesian fishert production totaled 24.85 million tons, with 7.99 million tons coming from fishing and 16.87 million tons from aquaculture. Compared to the 21.87 million tons of production in 2021, the total quantity grew by 13.63% [2]. Given this prosperity, Indonesia must put into practice an initiative that would enhance the country’s fisheries sector in a manner that is sustainable. In this instance, the blue economy provides an outlook for enhancing the economy and at the same time preserving the ocean and its ecosystem [3].

In 2012, the Rio+20 Conference introduced the concept of a blue economy. It bases itself on the idea that strong and thriving marine ecosystems are more effective and essential to the viability of ocean-based economies. From there, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) launched the Blue Growth Initiative (BGI), which aims to safeguard aquatic biodiversity and advance sustainable catch fisheries throughout the Asia–Pacific region [4]. Indonesia, a significant maritime nation, mostly depends on its oceans for economic expansion. As evidenced by the Djuanda Declaration, the country has prioritized the maritime industry since achieving their independence. Indonesian national regional plans started to incorporate the blue economy as a sustainable sector, with the National Long Term Development Plan (RPJPN) 2005–2025 emphasizing the sustainable use of maritime resources. When it comes to actualization, the productivity and significance of the fishing industry in Indonesia offer the greatest potential chances for the country’s blue economy. With an 8.2 percent share, Indonesia is the globe’s second-largest producer behind China thanks to its highly productive fisheries, and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for this sector in 2021 was 2.77 percent [5].

Fisheries have long played a significant role in the Indonesian economy, contributing to both increased national income and food security by ensuring nutritional sufficiency. As part of the aspects of blue economy initiatives, sustainable fishery practices must be implemented to support the integration of the blue economy framework into national policy. To further support integration in the region, Indonesia established cooperation with surrounding countries through an association body, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In 2021, a declaration was put forward by the ASEAN leaders on the blue economy at the 38th ASEAN Summit, which initially aimed to provide inclusive post-pandemic economic recovery for the ASEAN population. The declaration signified the reaffirmation of the ASEAN’s will to spearhead regional collaboration concerning the blue economy, with Indonesia being equally committed [6].

At its core, the blue economy is an approach that brings together environmental preservation and economic growth. The blue economy concept, which produces commodities along with ecological regulations, evolved as an initial step in accomplishing zero-waste industrialization [7]. The blue economy is defined by the European Commission [8] as all activity related to water and the seas. This suggests that in order for ocean resources to be looked after, human conduct ought to be controlled in a way that preserves the ecosystem of the seas and protects stable economic production. The ethical and responsible utilization of ocean resources for economic expansion, employment opportunities, and the overall wellness of the marine biosphere is embodied in this approach. The goal of a blue economy is to regulate conflicting interests and enable optimal growth across marine space without pushing economic interests ahead of societal or environmental considerations [9].

Studies on the blue economy, those related to its application in Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia, have been carried out several times by researchers. A broad discussion of the opportunities for implementing the blue economy in Indonesia can be seen from studies by Sari and Muslimah and Darajati [3,10], which discussed regulations for each fishery sub-sector to realize the marine economy as a support for the national economy. Developing from there, the marine industry has become a strong economic factor, explored in more studies, such as those carried out by Hartono et al., Nasution, and Zulkifli et al. [11,12,13].

Not only does the blue economy focus on economic problems, but, at the same time, it ensure that ocean resources, research on sustainable development, and the management of oceans are progressively discussed, as seen in studies by Medina and Enggriyeni and Aprilia and Mulyanie [7,14]. Drawing a link between the blue economy and social issues, Fudge et al. [15] conducted research suggesting that marine environments are critical to human welfare in a number of ways. Their research backs up the idea that political and cultural contexts should receive more attention, since marine industry growth is not managed in an approach that may have a detrimental impact on their impressions regarding regional wellbeing. Therefore, in the expanding marine sector, the blue economy concept is thought to be a suitable course.

In an increasingly developing blue economy concept, there is indeed the need for and importance of international cooperation for the effective implementation of the concept. Recognizing the institutionalization of cooperation as crucial in the notion, research by Lukaszuk [16] analyzed European Union and ASEAN acts as primary models of the two major global maritime areas. A study by Geng et al. [17] drew attention to the fact that broadening economic activity while lessening environmental impact is necessary for inclusive growth in Asia and emphasized the function of the Asian Cooperation Dialogue (ACD) in promoting inter-Asian connectedness. Southeast Asian waters wield a massive amount of biodiversity in their natural resources, so the potential for a vibrant blue economy is especially high in Southeast Asia. Recognizing the high potential for a blue economy in the Southeast Asia region, Gamage [18], Hananto et al., Setiawan, and Setiawan and Wahyudi [19,20,21] discussed the capabilities of the blue economy in the ASEAN specifically. In this case, the ASEAN, as a regional association body, is one of the important players for its member states to carry out negotiations and cooperation regarding the potential wealth of marine resources they have.

Yet, despite the increasing global focus on the blue economy, there remains a significant gap in understanding regarding the relationships between the ASEAN and its member states in implementing this concept. While Prayuda and Sary [22] analyzed Indonesia as one of the ASEAN member states in the strategy for implementing a blue economy, their study did not fully explore the broader dimensions of ASEAN cooperation as it is focused solely to the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). Given the increasing regional emphasis on sustainable fishery governance in economic development, there is a critical need to examine how Indonesia navigates its role within the ASEAN to promote the blue economy. This paper aims to investigate the power dynamics of Indonesia’s participation in the ASEAN in shaping regional blue economy initiatives. The study will explore Indonesia’s leadership strategies, assessing how its engagement affects regional outcomes. By doing so, this research seeks to provide a fresh understanding of Indonesia’s position in the ASEAN’s blue economy discourse and its implications for regional economic and environmental governance.

2. Materials and Methods

Academics and institutional bodies have given many interpretations to the concept of the blue economy. Despite some degree of similarity across the various definitions, the World Bank [23] said that there is no universally recognized definition of the phrase “blue economy”. However, as for the World Bank, they identify it as the preservation of the health of ocean ecosystems through the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic development and better livelihoods. It is believed that the blue economy necessitates pursuing the growth of oceanic sectors in an integrated manner while keeping track of the impact they have on the wellbeing of the ocean.

From then on, the idea developed and was incorporated into laws and policies so that countries could put it into practice. In connecting to Indonesia, the “blue economy” is defined as an approach to promote sustainable ocean governance and the preservation of ecosystems in order to drive economic growth by means of community involvement, efficient use of resources, and reducing waste, as stated in Article 14 Paragraph 1 of Law Number 32 Year 2014 related to the Sea. Yet, regardless of distinctions in explaining the concept, each of the interpretations include the urgency of balancing the need to use marine resources for development while reducing, or even eradicating, the possibility of negative impacts to the ocean.

This study employs a qualitative research design to analyze Indonesia’s role in the ASEAN’s blue economy initiatives through the lens of Gramsci’s hegemony theory. Within the notion, the depiction of power goes above military strength in arms by incorporating both tangible and intangible means. Historically, Gramsci views ideas and material circumstances to have always been interconnected and mutually influential. The theory of hegemony highlights the impact of social views by using ethical consensus that is closely linked to global power structures. The Gramscian theory focuses on a form of hegemony that manifests in accords and the recognition of ideas that are ultimately reinforced by institutions and material factors that are formed by social power [24].

To further understand how Indonesia has advanced its leadership in the region, a combination of thematic analysis and literature review is applied. The primary data consist of relevant speeches by Joko Widodo (now-former president) from regional and global forums in 2023, as well as the ASEAN leaders’ speeches from the ASEAN Blue Economy Forum 2023. These speeches were sourced from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) of Indonesia and the recorded meeting of the ASEAN Blue Economy Forum 2023, which was taken from the official YouTube account of the National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) of Indonesia. A thematic analysis was conducted to identify patterns in discourse and policy framing in Widodo’s and the ABEF speakers’ speeches. The speech records were transcribed and then coded based on three categories of materiality, ideas, and institutionalism, derived from Gramsci’s theory of hegemony as an analytical lens.

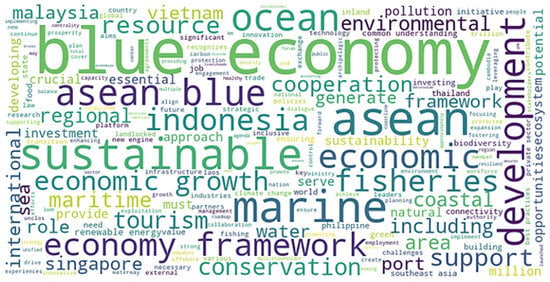

Once the dataset has been defined by themes related to Indonesia’s diplomatic strategy in the ASEAN, its patterns of repetitive keywords are then identified in pinpointing narratives that Indonesia often uses in advancing regional dialog. All speeches relevant to themes of blue economy inclusion were used in the thematic analysis to identify patterns in discourse and policy framing. Through an analysis of significant speeches, we demonstrates how Indonesia promotes itself as a driver for economic cooperation, strategic regional influence, and ocean governance. The themes highlight the unifying role of the sea and the necessity of collaboration for sustainable regional growth. Table 1 will show a thorough summary of Widodo’s speech, displaying key phrases that are often mentioned in his speech, while Figure 1 contains a word cloud visualization of remarks from the ABEF speakers. To note, word cloud visualization depicts keywords in which the dimension of each word corresponds to the frequency with which it appears throughout the dataset. For reference, the Supplementary File contains the entire dataset, which includes a thorough classification of thematic components.

Table 1.

Patterns show in keywords and phrases based on data of speeches by Joko Widodo.

Figure 1.

Word cloud visualization of patterns shown in key quotes by speakers based on data of ABEF 2023.

To complement the speech’s data in providing contextual support for the analysis, secondary data in the form of policy reports and the academic literature were collected through publications, including reports and policy briefs from the ASEAN Secretariat, the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MOFA/KKP), BAPPENAS, and peer-reviewed journal articles on blue economy frameworks in Southeast Asia. Analytical findings were then compared against the ASEAN declarations and Indonesian policy documents to ensure alignment with formal blue economy initiatives, cross-referencing it with policy documents. With the use of the concept and theory as a lens, the study will further look at Indonesia’s power dynamics within the ASEAN, as an actor that directly engaged with the issue discussed.

Recurring themes of Widodo’s speeches (Table 1) and speaker’s speeches at the ABEF 2023 (Figure 1) were then analyzed to further validate Indonesia’s leadership strategies. Speeches were evaluated using thematic analysis to detect patterns of interpretation within data, revealing the underlying narratives that shape Indonesia’s role in the ASEAN. These findings demonstrate that Indonesia’s blue economy leadership is reinforced through a combination of material strength, persuasive narratives, and institutional leverage. Discussion will address on the identified keywords and phrases that form the key elements of the thematic analysis, with comprehensive data from the speeches available in Supplementary File. By integrating qualitative content analyses with theoretical insights, this study systematically examines Indonesia’s leadership role in the ASEAN’s blue economy agenda.

3. Theoretical Framework

Indonesia, as a nation of islands, with oceans covering the majority of its landmass, has yet to be able to optimally utilize its maritime resources and capacities. An innovative approach to the blue economy is regarded as a valuable new engine for enhancing economic growth while also protecting the marine ecosystem. Questionnaire data for the FAO’s 1995 Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) further demonstrate Indonesia’s attention to advance sustainable fisheries. Attending the 2023 Committee on Fisheries (COFI) international meeting, Sakti Wahyu Trenggono, Minister of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, believed that Indonesia’s marine and fisheries sector would play a significant role in providing the world’s food demands, with the implementation of blue economy initiatives through its fishery production [25].

Oceans are global in nature; hence, issues pertaining to them are likewise global in scope. The entire approach must be transformed in order to optimize innovative improvements to inclusive and sustainable marine resource management. By far, the ASEAN makes up part of Indonesia’s inner circle priority of foreign policy, and Indonesia’s approach to pushing influence through the institution was through initiatives that represented their progress in democratization [26]. By considering both the ideological concept and the cultural values that impact the development of the blue economy in the area, a deeper understanding of the interplay between Indonesia’s material and immaterial resources may be measured.

Using the hegemony theory by Gramsci, the power structure of Indonesia in the ASEAN can be explored through three elements. Hegemony entails the incorporation of dialog into an integrated ideology and institutions that demonstrate the ethical supremacy of ruling ones. In the words of Gramsci, the emergence of a hegemonic culture that molds the views, values, and practices of society is another way that those who rule keep their hold on power, complementing economic dominance and armed force [27]. It posits that power is maintained through a combination of material dominance, ideological leadership, and institutional structures. Through reinforcing the prevailing ideology, this hegemonic culture is spread through a variety of institutions using material resources to gain ethical power.

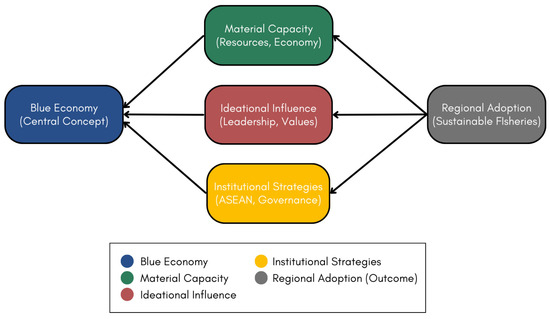

The dynamic of the three main elements of materiality, ideas, and institutions reinforces the consent-based power of hegemony theory. Materiality can be seen as a tangible component of a country’s resources, as in Indonesia’s economic and resource-based leadership in the blue economy. Material power is subsequently transformed into a consensual and a cooperative system, with ideological approaches rooted in the shared values of interest, including the narratives Indonesia promotes in the ASEAN. To formalize the hegemon’s leadership, therefore, institutions came into play in creating a mechanism to ensure that shared values are practiced and decisions are reached with consent, through which Indonesia integrates the blue economy policies within the ASEAN frameworks [28]. As seen in Figure 2 below, in order to establish a dominant position toward embracing sustainable fisheries as a vital part of the regional blue economy, the three factors cooperate.

Figure 2.

Analytical framework: Indonesia’s blue economy leadership in ASEAN through Gramsci’s hegemony theory.

3.1. Material Capacity

Indonesia’s waterways include some of the world’s richest fisheries and marine biodiversity, which directly boosts the country’s economy and food security. Right after China, Indonesia is the second-largest seafood producer worldwide, with fisheries contributing 2.7 percent of its GDP in 2021 [5]. Reported from KKP [29] statistical data, the total volume of Indonesian fishery production in 2023 reached 24,737,618 tons, and it has been increasing since. Furthermore, economically, Indonesia is the biggest country in Southeast Asia, and in the past few years, it has effectively drawn international spotlight as a shining star in Asia, transforming the economy into a strong rising-power country [30].

When it comes to the blue economy, Widodo said that his nation had the richest underwater ecosystem. He also reaffirmed that all of Indonesia’s marine areas must prioritize the sustainable blue economy as part of their goal. Following that, Indonesia needs to make good use of these resources to raise people’s standard of living while preserving the environment and ethical manufacturing. As per BAPPENAS, the country’s maritime resources are expected to provide an astounding USD 30 trillion in economic output by 2030. On top of that, the World Bank calculated that Indonesia’s ocean economy, wherein marine construction and manufacturing are its two main sectors, is worth around USD 280 billion yearly [9,31].

The growth of Indonesia’s ocean economy has assisted in the nation’s economy growth since the Asian financial crisis of 1997, making it an economic powerhouse in Southeast Asia and an upper middle-income nation as of 2019. Among the ASEAN nations, Indonesia produced the most value added from maritime transportation of passengers and freight in 2015, with a combined worth just above USD 4 billion [9]. Yet, despite the anticipated value of the blue economy, Indonesia’s use of ocean economies remains limited to traditional business sectors. Even so, the blue economy is expanding swiftly over time. The blue economy surged at a rate of 10.5 percent each year until 2020, considerably faster than the roughly 5 percent national growth average. This suggests a huge potential if investments are effectively set up, which also corresponds with the Indonesian 2045 Vision, where the contribution of the blue economy is predicted to reach 12.45 percent of national GDP by 2045 [9,32].

In spearheading the ASEAN blue economy agenda, Indonesia makes sure regional efforts support its own objectives in creating sustainable strategies in the maritime industry. Indonesia’s dedication to maritime security structures, such as measures to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, further indicates its ability to preserve regional waters and the ASEAN’s shared resources. By taking the lead in combating IUU fishing with Task Force 115, Indonesia has demonstrated to the world its commitment to ending sea good trafficking in Indonesian waters. They additionally implemented the Integrated Maritime Intelligent Platform to employ intelligence tools to assist Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance (MCS) in exposing more diverse forms of illegal fishing. Moreover, Indonesia was the first country in the ASEAN to share its Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) data with the Global Fishing Watch. [32,33,34]. Through these instances, Indonesia has demonstrated its commitment and ability to build infrastructure that will support its marine agenda going forward.

3.2. Ideational Influence

The presence of Indonesia within the ASEAN is closely connected to the country’s past regional leadership, even portrayed as the de facto leader of the association. As the self-described “natural leader” or “primus inter pares” of the ASEAN, Indonesia has continuously contributed a significant amount to the Southeast Asian region [35]. Being one of the founding states of the ASEAN and as the largest region, Indonesia has long engaged in preserving regional stability and cohesion since the establishment. The process of implementing the blue economy concept is also an important reminder that Indonesia continues to maintain its reputation as a pioneer of the concept that forms the ideational basis of the ASEAN.

Maintaining the ASEAN’s autonomy in regional situations has long been a key component of Indonesia’s foreign policy and its role within the association. As an outgrowth of its internal politics, Indonesia, for instance, has worked toward human rights in the ASEAN for the last few decades [36]. Corresponding to that, environmental matters have gradually become a topic in this role. As a facet of its leadership efforts in the ASEAN, Indonesia is viewed as an environmentally aware nation pursuing sustainable methods. This was also seen in the 2022 G20 Presidency, where Indonesia showed leadership and a high commitment to various strategic issues, one of which was environmental management. In the Climate Sustainability Working Group (CSWG), the discussions included strengthening action and partnerships for sustainable marine initiatives [37].

As a major maritime power, Indonesia has long given priority to its marine industries, focusing on improving structures and advancing diplomacy through the Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF) model. Through the incorporation of blue economy ideas into its vision, Indonesia strives to achieve sustainable growth in its fishery sector. This approach is one of the important pillars in its long-term economic growth strategy, especially as it creates added value from Indonesia’s marine resources [38]. As the holder of the 2023 ASEAN chairmanship, Indonesia is committed to delivering the ASEAN Blue Economy Framework as one of the economic goals of 2023. With the given ideas under consideration, Indonesia has prospered in developing sustainable marine industries and the blue economy as a foundation for the ASEAN’s ongoing economic integration [39].

Indonesia nurtures a sense of regional identity based on the ASEAN’s common maritime legacy and economic situation. As every ASEAN member country is connected by oceans, Indonesia framed the blue economy as central to the ASEAN’s sustainable development, emphasizing that healthy oceans and sustainable marine industries are essential to regional prosperity. Highlighting the sea as an anchor for the ASEAN’s goals in economic leadership, Indonesia promotes ASEAN-wide cooperation on maritime connectivity under the theme Epicentrum of Growth. By effectively aligning the national vision with the ASEAN’s objectives and values, this cultural framework places Indonesia as the region’s natural leader and the blue economy as a natural continuation of the ASEAN’s maritime culture to build upon concrete cooperation.

3.3. Institutional Strategies

Formal institutions like the ASEAN are essential in giving member states formal regulations and a legal framework to govern their interactions. The institutional structure of the ASEAN provides a solid basis for its member states to cooperate on regional concerns, including ecological and socioeconomic matters [40]. Although Indonesia’s lobbying is framed structurally by the ASEAN’s formal institutions, ASEAN values also play a significant role in furthering the agenda of the blue economy. The ASEAN Way, specifically, promotes consensus-building and acknowledges the sovereignty of member states. Through these informal means, Indonesia could push the idea of the blue economy without seeming to impose its will on its national laws.

The ASEAN Way refers to the concepts and rules that govern interactions among ASEAN member countries. Using consensus to make decisions and the nonviolent resolution of conflicts are two examples of these concepts [41]. The key to the ASEAN’s administration is reaching a consensus among its member states. This consensus is built on the understanding that the regional interests are interconnected with the national interests of each member state [42]. This principle has been a ‘way’ for the ASEAN and its member states ever since the Bangkok Declaration including Indonesia. Through the ASEAN Way, Indonesia’s emphasis on collective agreement ensures that its leadership in the region is framed as cooperative rather than domineering.

Academics and leaders in Indonesia have turned to the notions of “ASEAN centrality” and the ASEAN being the “cornerstone” of Indonesian foreign policy repeatedly to influence the perception of Indonesia’s place in the ASEAN both locally and globally. Indonesia, through the ASEAN, has been attempting to lessen security competition in order to create a setting that is favorable to economic development. This strategy is in line with Indonesia’s foreign policy, which uses free-active politics to help shape the country’s international identity [43]. By emphasizing consensus through the ASEAN Way, Indonesia respects the sovereignty of other ASEAN members, building trust and facilitating voluntary cooperation instead of top-down directives. President Joko Widodo also emphasized that Indonesia prioritizes and respects the value of equality among ASEAN countries in Southeast Asia. The implementation of the value of equality is said by the President of the Republic of Indonesia to be a key factor in strengthening unity in the region, especially in facing global challenges [44].

The ASEAN Charter officially set the chairmanship of the ASEAN to be rotated annually, and Indonesia took over as chair once more in 2023, after last occupying the position in 2011. Chairmanship not only confers significant status to the state serving as chair for the year, but it also gives the state a chance to set prioritize and implement policy decisions on behalf of all members of the ASEAN bloc [45]. Even prior to its 2023 chairmanship, Indonesia was considered to be able to steer the ASEAN towards changes that strengthen the organization’s institutional framework and increase its prominence in the region’s political sphere [46].

Building an additional emphasis on post-COVID-19 regional recovery, Indonesia further stressed the growing importance of the blue economy as part of its plan. Utilizing procedures centered around ocean governance, the ASEAN recognized the oceans as important engines of economic growth, as indicated in the 2021 Declaration of the Blue Economy. With the assistance of the Economic Research Institute for the ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), the BAPPENAS hosted the initial ASEAN Blue Economy Forum (ABEF) on 2 to 4 July 2023 under Indonesia’s chairmanship, bringing together policymakers and academics to shape regional blue economy initiatives. The discussion board represented a major step in the completion of the ASEAN Blue Economy Framework, which was approved by ASEAN leaders at the 43rd ASEAN Summit [47]. With this, Indonesia, through the BAPPENAS, when it was assigned as chair, spearheaded ideas for developing blue economy cooperation by building a framework that had been agreed upon by ASEAN member states as a fulfillment of the mandate of the 2021 Declaration.

4. Discussion

4.1. Framework Dynamics and Regional Adoption of Sustainable Fisheries

In keeping with Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, power by consent arises when institutions, ideas, and materiality intersect to form a legitimate leadership structure. The aforementioned findings make this interaction apparent in the context of Indonesia’s power dynamics in the ASEAN, especially with regard to its maritime vision. Indonesia ensures that its leadership in the region is viewed as both natural and necessary by fostering alignment and collaboration through the combination of its institutional influence, ideas, and material qualities.

Indonesia’s position as chairman of the ASEAN in 2023, especially, plays a leading role in ensuring the development of the blue economy in the region. Once it was assigned as chair, Indonesia managed to take the opportunity to build hegemony in the ASEAN by incorporating elements of power. Indonesia’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs, during the chairmanship, said in the Plenary Session of the 43rd ASEAN Summit that ASEAN leaders appreciated Indonesia’s chairmanship of the ASEAN in 2023 and considered that Indonesia produced many achievements even in difficult situations. The statement also mentioned the ASEAN’s recognition of Indonesia’s role in developing the maritime agenda and that the blue economy is a new source of sustainable development in the region [48]. This can be an attestation to the consent that Indonesia received, making the hegemon legitimized and accepted wholly from the surrounding regional countries during its leadership.

4.2. Material Resources: Transforming Material Dominance into Shared Values and Regional Leadership

Through its president, Indonesia further restated emphasis on materiality, emphasizing the strategic and economic importance of the sea and growth as critical components of the ASEAN’s regional influence. As every ASEAN member country is connected by oceans, Indonesia framed the blue economy as central to the ASEAN’s sustainable development, emphasizing that healthy oceans and sustainable marine industries are essential to regional prosperity. During the First Summit of the Archipelagic and Island States (AIS) Forum, President Widodo underlined his maritime connectivity narrative with phrases on the line of “Laut bukanlah pemisah antar daratan tapi laut justru pemersatu antar daratan. Laut justru perekat dan penghubung antar daratan”, which translates to “The sea is not a divider between land, but the sea is actually a uniter between land. The sea is actually the glue and connection between land” [49]. With material assets of rich biodiversity and fishery output inherent to an archipelagic state, he promotes broad trends such as cooperation, security, and shared responsibility, all of which are critical for building regional integration. This notion of the sea (laut) as a unifier appears as a trend that is often brought up in ASEAN summits, with partner countries highlighting the potential of navigating challenges into an opportunity for development.

In a similar pattern, President Widodo, as conveyed in the ASEAN Leaders Meeting with the ASEAN Business Advisory Council (ABAC) 2023, stated that “the economic potential of our region is very large with an economy growing above the world average” [50]. The blue economy, a key engine of economic expansion, promotes sustainable development in the marine industry to establish interrelated economic activity. As pointed out by Widyasanti of the Indonesian Ministry of Economics at the ABEF 2023, “Blue economy can provide interconnection from inland to oceans… a new engine of economic growth”, [51]. This emphasizes how important the blue economy is in creating an inclusive, innovative, and resilient economic structure that fosters prosperity both nationally and regionally. Along with its leadership position, Indonesia continues to invite collaboration, formulating a joint agenda to ensure the region’s position as the Epicentrum of Growth.

Other countries have expressed their support for Indonesia’s leadership in driving the blue economy forward. Cambodia, through Heng Sarith, recognized Indonesia’s efforts, stating “Cambodia fully support Indonesia’s theme for 2023, as in mirror epicenter of growth, recognizing the private total of blue economy play in driving economic development, ensuring economic security and resilience of the region. We firmly believe that the blue economy hold the key to unlocking a new era of sustainable growth, innovation, and prosperity for ASEAN and its people”. Similarly, the Philippines acknowledged Indonesia’s influence, suggesting that its initiatives serve as an inspiration for other nations, as noted by Quintana: “Actually, I was very inspired by the launching of the Indonesian Blue Economy Roadmap … I will definitely report that to the Philippines and share the publication that was distributed earlier”, [51]. Indonesia’s regional leadership, as one of the ASEAN’s founding states, effectively adjusted its material dominance into shared values of member states. These endorsements demonstrate that ASEAN member states view Indonesia’s leadership as instrumental to working together to implement the blue economy as a regional priority.

4.3. Ideational Influence: Framing Blue Economy Priorities Through Consensus and ASEAN Identity

By means of its positions in the ASEAN, especially during its 2023 chairmanship, Indonesia was able to effectively deliver the blue economy to the regional agenda, enhancing its ideological dominance. Monoarfa of the BAPPENAS further pointed out the commitment of Indonesia “to deliver the ASEAN Blue Economy Framework as one of priority economic deliverables in 2023… a continuation of the ASEAN leaders declaration on blue economy in Brunei Darussalam in 2021 as a collective effort of ASEAN member states to mitigate the impact of COVID-19” [51]. Narratives of cooperative habits and sense of shared responsibility brought up by Indonesia in the ASEAN forums underline efforts of regional integration. In the 43rd ASEAN Summit Plenary Session, Jokowi used his session to stress the magnitude of current global challenges, indicating that the main key to facing them is ASEAN unity and centrality. He stated “ASEAN’s direction is clear, to become the epicentrum of growth and has great resources to achieve this. But ASEAN must be able to work harder, be more unified, be braver and be more agile” [52]. When the frequency of words used in his speech is analyzed, the word “cooperation” appears 25 times, whereas “collaboration” is mentioned 12 times. This trend underscores Widodo’s demand for members to prioritize concrete cooperation in order to produce effective collective efforts in addressing shared responsibilities.

Equipped with the narrative of the sea as a crossroads, Indonesia further highlights the rich biodiversity of the area as the main force driving cooperation. As long as the region is still bound together by water, the concept of shared responsibility serves as an engine for concrete collaboration in this area. Considering the growing environmental degradation of marine habitats, regional collaboration is essential to improve the stability and long-term viability of ocean-based manufacturing sectors to set up a path of sustainable and inclusive growth for all. By leveraging ASEAN identity and vision, Indonesia leads by prioritizing regional maritime narratives through building consensus to push the blue economy forward.

Strong institutional support is crucial in order to convert concepts into workable policy. Indonesia places a strong emphasis on the value of inclusive participation, making sure that stakeholders from the public and corporate domains actively participate in decision-making processes. At the ABEF 2023, the UN Resident Coordinator of the Republic of Indonesia, Julliand, further underscored, “Involve everybody… It should not be a top-down approach. It has to be a bottom-up approach”, [51]. Through the inclusion of diverse stakeholders, institutions may adopt adaptable policies that will ensure the ongoing success of developing blue economy. The ASEAN Coordinating Council (ACC) assigned the High-Level Task Force on ASEAN Economic Integration (HLTF-EI) to oversee the creation of an ASEAN Blue Economy Framework as a follow-up to the Declaration on the Blue Economy. This framework intends to give the ASEAN community’s general principles and tactical guidance on the blue economy. By establishing a new value chain throughout the region and promoting ASEAN centrality, the framework will facilitate the shift in direction of the blue spirit [53]. Such a dynamic demonstrates Indonesia’s capacity to foster common ground among ASEAN nations, ensuring that the blue economy is viewed as an equal chance for progress rather than the enforced ambition of an individual state.

4.4. Institutional Strategies: Deploying Resources and Governance Structures to Advance Blue Economy Objective

Possessing full of fisheries and vast coastlines, Indonesia capitalizes on its material strength through institutional methods that turn its resource strengths into practical regional frameworks. Indonesia has been actively utilizing its capacity to progress towards a blue future, as indicated by Monoarfa of the BAPPENAS: “Under the G20 presidency, Indonesia successfully initiated the Global Blended Finance Alliance to mobilize new sources of development financing from non-government actors. Indonesia also launched the Blue Halo S Initiative to showcase a blueprint to tackle the finance gap… ASEAN can take the benefit from the global blended finance alliance for unlocking the economic potential of us” [51]. This tangible base strengthens its legitimacy, allowing Indonesia to portray itself as both a leader and supporter of sustainable marine practices in the ASEAN.

While Table S2 shows the comprehensive dataset of speech data, Figure 2 displays key words delivered by speakers based on data from their speeches at the ABEF 2023. The heavy use of the term “blue economy”, mentioned 65 times, alongside “sustainable”, “marine”, and “development” indicates the speakers often centered their talks on the environment and economy, coupled with the phrase “economic growth”. Another significant factor comes to be “Indonesia” and “ASEAN”, projected to focus on Indonesia’s leadership role in furthering the ASEAN-wide agenda for the blue economy. Furthermore, the ASEAN member states’ involvement in the forum points out the regional context of the discussions in promoting the ASEAN’s ambition to develop an integrated blue economy framework, with frequent mentions of “cooperation” and “connectivity”, implying a priority on regional policy integration and collaboration in governance.

To further demonstrate the significance of comprehending Indonesia’s institutional strategy for visualizing the ASEAN’s engagement in blue economy endeavors, a repeating subject in Widodo’s speech takes the form of the ASEAN as the Epicentrum of Growth. As mentioned in the ASEAN Leaders’ Interface with Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, narratives aim “to ensure that ASEAN is more responsive and resilient in facing challenges to be a center of growth and a safe, stable and democratic region. Collaboration between the Government and Parliament must be strengthened to ensure that ASEAN becomes the Epicentrum of Growth” [54]. The line emphasized the commitment to further reinforce the ASEAN’s unity and centrality in the initiatives of economic development and sustainability for its stability. At center stage, ASEAN platforms are recognized as the norm-setting tool for integrating the blue economy into the regulatory discourse of the ASEAN region.

By ensuring that ASEAN member states are engaged in concrete cooperation to harness the whole potential of their maritime resources through the blue economy, in the 43rd ASEAN Summit, Widodo further underlined the importance of the framework of unity within member states. To be more precise, he narrates it as “the world’s oceans are too vast to sail alone. On our journey (onwards) there will be other ships, ASEAN partners’ ships. Let us together realize equal and mutually beneficial cooperation to sail together towards the Epicentrum of Growth” [55]. With the growing view of the sea as a unifier, the ASEAN is further portrayed as the sea’s vessel, where each nation plays an integral role in steering the region toward shared prosperity.

Statements reinforcing the ASEAN’s central role also come from other member states that expressed strong support for collaboration and reaffirmed the association’s role as the primary institution for advancing the blue economy. Laos recognizes that a collective commitment comes from a joint initiative across the region, especially through knowledge-sharing, as stated by Douangchak: “It is highly recommended ASEAN member states should continue to exchange lessons learned, experience and best practices on blue economy development in the future”. In the same context, Malaysia, through Lukman bin Ahmad, highlighted the necessity of engagement between stakeholders in developing national and regional blue economy strategies: “Despite several issues that we are facing now, such as economic structure, human capital, laws and regulation, we will come up with our blue economic blueprint … we will embark a study this year which will involve all stakeholders, including local and international. For that, we expect to get cooperation from all of us here today, especially Indonesia” [51].

Indonesian governance allows a consensus on the blue economy, harmonizing member states’ interests with regional ecological and economic targets. By underscoring that the sea is a shared space of opportunity, Indonesia further drew on the ASEAN’s vision towards positioning the region as the epicentrum of growth. Its leadership played a key role in shaping a unified view for cooperation, reflecting that the ASEAN countries may address collective issues by utilizing effective actions and working together. The remarks further emphasize the ASEAN’s significance in bringing together efforts to increase regional economic resilience and ensure that the blue economy remains an inclusive and sustainable engine of growth for all member states.

4.5. Outcome: Regional Adoption of Sustainable Fisheries

The ability of Indonesia to uphold its hegemony in the region relies significantly on the dynamics and the interplay across all three elements of power within Gramsci’s theory of hegemony. Collectively, each of these variables have implications for the region’s blue economy endorsement in the ASEAN, which entails developing a thorough strategy that integrates resources, goals, and mechanisms to promote a sustainable fishery sector. While ideology reinforces the framework that generates a shared agenda when its institutional strategies bring in means to enforce actions and set up norms, Indonesia’s material capacity encourages credibility to secure conformity. This ensures that the blue economy is more than a national mission, a regionally integrated initiative promoting participation and shared growth across ASEAN member states. Indonesia is able to portray its agenda as advantageous for the area by taking on the role of a collaborative leader as opposed to a controlling leadership.

Gramsci here emphasizes the significance of consent in contrast to conceptions of pure coercion, which makes the theory valuable in describing how hegemony and global systems persist without the presence of an ongoing force. Legitimation based on common values and interests is the foundation of Indonesia’s ethical–political leadership. The speeches demonstrate a calculated and strategic usage of the overarching themes of cooperation and ASEAN centrality to underline the regional role in the blue economy. This continuous narrative demonstrates Indonesia’s commitment to regional leadership, emphasizing unity and centrality as essential drivers for sustainable economic growth in the fishery sector through the blue economy. Recognizing Indonesia’s regional relevance requires an alignment between its material strengths, ideational influence, and institutional approach. At the end of Indonesia’s 2023 chairmanship, empirical results of tangible deliberations showcased its ability to lead the regional bloc effectively.

Through the ABEF 2023, in-depth talks on sustainable marine resource management and business prospects across the bigger picture of the blue economy were fostered by the three-day forum. Realizing the value of a structured strategy, Indonesia spearheaded the way by releasing the Blue Economy Roadmap, proving its commitment and determination to lead this endeavor. The roadmap, which outlined key goals and practical steps for sustainable sea management, acted as a guide for ASEAN nations. As also noted by Pierra Tortora of the OECD Sustainable Ocean for All Program, “Indonesia launched today the Indonesia Blue Economy Roadmap… forming the basis for the framework,” [51,56]. With that, along with ASEAN members, the OECD took note of Indonesia’s leadership in expanding the blue economy, acknowledging its contribution in pushing global discourse on sustainable marine governance. On top of that, during the 22nd meeting of the AEC Council, Indonesia further organized a plenary Special Retreat Session on Sustainability Initiatives to examine the ASEAN Blue Economy as the region’s new growth engine [57]. By enabling stakeholders to coordinate their perspectives and contributions, such dialogs assisted in defining regional goals that had a substantial impact on the framework’s final draft. Its formal approval as a regional model for the blue economy was made achievable in large part by Indonesia’s leadership in directing these talks.

Recognizing the blue economy’s critical role, ASEAN leaders unanimously supported its development during the Republic of Indonesia’s chairmanship. Under the tagline ASEAN Matters: Epicentrum of Growth and throughout discussion in the ABEF 2023, the framework’s acceptance demonstrates a shared dedication to a blue future. As stated in the Chairman’s Statement at the 43rd ASEAN Summit, the ASEAN Blue Economy Framework aims to “elevate ASEAN’s collaborative efforts on blue economy in an integrated, cross-sectoral and cross-stakeholder approach that creates value-added and value-chain of resources from oceans, seas and fresh water in an inclusive and sustainable way, making blue economy a new engine for ASEAN’s future economic growth”. The milestone highlights the effective attempts by Indonesia to bring member nations together for deeper regional cooperation in the blue economy sector, as well as the ASEAN’s commitment to economic resiliency [58]. Additionally, Indonesia has taken the lead towards assisting ASEAN nations in marine affairs, including in establishing common IUU fishing policies, such as drafting the Guidelines for Preventing the Entry of Fish and Fishery Products from IUU Fishing Activities into the Supply Chain [32].

Rather than pressuring countries to comply with the policies, Indonesia thoroughly lobbies for regional frameworks and ASEAN-led structures, acknowledging the reciprocal advantages of a circular economy. As an example, Timor-Leste, a newly admitted member, has only begun to bridge its national policies with regional frameworks of the ASEAN. Nonetheless, Indonesia has set up a regional narrative that even new members of ASEAN accept by presenting the blue economy as a crucial structure for sustainability and economic resilience. As evidence of its endorsement of the ASEAN’s common vision, which Indonesia has actively molded, Timor-Leste is actively seeking to incorporate blue economy ideas into its national development plans, disregarding its small economy. To even speed up its transition to a sustainable fishery sector, the ASEAN Blue Economy Innovation project, supported by the Government of Japan and executed by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Indonesia, was developed to support creative thinking toward blue economy initiatives within the ASEAN [59].

Through the ASEAN Blue Innovation Challenge project, Timor-Leste expressed commitment to the blue economy’s potential to promote the nation’s future development. Hundreds of local entrepreneurs and creative thinkers applied to the Blue Economy Ideation Workshop to work together to figure out urgent issues impacting Timor-Leste’s coastlines and marine ecosystems. By setting an ideal example for being a maritime powerhouse, Indonesia enabled Timor-Leste to see the blue economy as a practical long-term development plan. Timor-Leste took advantage of ocean governance capacity-building initiatives led by Indonesia, which increased its regulatory and human resources for ecotourism and fishing-related sectors [60]. The blue economy was made a regional focus under Indonesia’s 2023 ASEAN Chairmanship, and the involvement of Timor-Leste with this agenda demonstrates Indonesia’s effective use of consensus-based leadership (Figure 3).

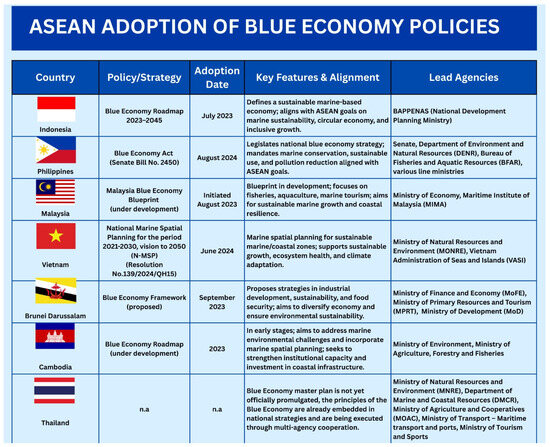

Figure 3.

The enforcement of blue economy policies in ASEAN governments.

The graphic above illustrates adopted blue economy policies throughout the ASEAN, with Indonesia setting the way by announcing its plan of action. The roadmap showcased its dedication to the endeavor, served as a reference for member nations, and acted as the foundation for the framework that followed. Following the ratification of the ASEAN Blue Economy Framework in 2023, member states started drafting their own blue economy plans in an attempt to integrate their national agendas. Albeit certain ones, such Thailand, have yet to endorse an official blue economy plan, the concepts of sustainable maritime governance are becoming more and more ingrained in the national policies of ASEAN countries. Nonetheless, taking into account Indonesia’s substantial impact in guiding the ASEAN towards an integrated blue economy approach, member nations, including Malaysia and Vietnam, took initiative by developing their own ocean management based on sustainability objectives [47,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76].

In alignment with the ASEAN chairman rotation regulations, as 2023 ended, Indonesia’s chairmanship concluded and was resumed by Laos in 2024. The programs and structures it created, however, still influence the regional plan of action and provide a solid basis for the next chairing nation to construct around. The summit and the blue economy framework provide a setting for continued partnership and interaction, guaranteeing that the ASEAN’s goal of a thriving and sustainable blue economy is a top priority. In 2024 with assistance from the Indonesian government, the Lao PDR’s Ministry of Industry and Commerce hosted the inaugural meeting of the ASEAN Coordinating Task Force on Blue Economy (ACTF-BE) in Vientiane, Laos, where key ASEAN officials gathered to push the endeavor. The forum addressed ACTF-BE governance as well as its contributions to the AEC Strategic Plan 2026–2030 and formulation of ASEAN’s Blue Economy Implementation Plan [77]. These deliberations not only indicate Indonesia’s lead in pushing ASEAN’s maritime agenda but also suggest the region’s dedication in collective targets on economic development, sustainable development, and stability across the region.

5. Conclusions

Jalesveva Jayamahe, “Our Glory is at the Seas”, is Indonesian Navy’s motto that keeps Indonesia committed to its objective of making maritime and fishery sectors advance through the blue economy. By integrating economic dominance, ideational narratives, and institutional mechanisms, Indonesia has positioned itself as the central driver of the ASEAN’s blue economy agenda. Rather than imposing unilateral policies, Indonesia fosters consensus-based leadership, ensuring that the ASEAN’s sustainable fishery initiatives are widely accepted. It therefore demonstrates Gramsci’s claim that legitimate hegemony rests on ideological alignment, which in this case enabled Indonesia to exercise its power in the ASEAN by obtaining consent instead of centering entirely on coercion. In doing so, as the study reveals, Indonesia’s chairmanship in 2023 was instrumental in formalizing the ASEAN Blue Economy Framework, setting the stage for continued regional cooperation in maritime sustainability. The blue economy framework is a groundbreaking approach to preserving the environment and resilience in the economy, as long as the ASEAN puts a high priority on it, ensuring the region’s role in sustainable development globally. The fulfillment of this vision will come down to member states’ shared commitment in synchronizing national policies with regional priorities and on its next chairmanship. As this study primarily focuses on Indonesia’s role, particularly during its 2023 chairmanship, it does not comprehensively examine the responses of other ASEAN member states, which may influence the long-term success of the initiative. Therefore, observing how other ASEAN nations embrace or reject Indonesia’s blue economy initiatives and measuring the success of the blue economy framework over time are suggested areas for further research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17156906/s1, Table S1. Data of Jokowi Widodo’s speeches at regional and global forums throughout 2023; Table S2. Table on data of Speaker’s speeches at ASEAN Blue Economy Forum 2023; Table S3. Word frequencies on speaker’s speech at ABEF 2023; Table S4. Word frequencies on Widodo’s speech at regional and global forums throughout 2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S. and R.A.P.; methodology, O.S. and R.A.P.; software, O.S. and R.A.P.; validation, R.A.P.; formal analysis, O.S.; investigation, O.S.; resources, O.S. and R.A.P.; data curation, O.S. and R.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S.; writing—review and editing, R.A.P.; visualization, R.A.P.; supervision, R.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC will be partly funded by our institution (BINUS University).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in https://kemlu.go.id/publikasi/pidato/pidato-presiden (accessed on 13 January 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASEAN | ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| ABEF | ASEAN Blue Economy Forum |

| ACC | ASEAN Coordinating Council |

| AEC | ASEAN Economic Community |

| ASWGFi | ASEAN Sectoral Working Group on Fisheries |

| ACD | Asian Cooperation Dialogue |

| BGI | Blue Growth Initiative |

| CSWG | Climate Sustainability Working Group |

| CCRF | Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries |

| COFI | Committee on Fisheries |

| ERIA | Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GMF | Global Maritime Fulcrum |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| HLTF-EI | High-Level Task Force on ASEAN Economic Integration |

| IUU | Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated |

| MOFA | Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

| MMAF/KKP | Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries |

| BAPPENAS | Ministry of National Development Planning |

| MCS | Monitoring, Control, and Surveillance |

| RPJPN | National Long Term Development Plan |

| SP-FAF | Strategic Plan of the ASEAN Cooperation in Food, Agriculture and Forestry |

| OECD | The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

References

- Pane, D. Blue Economy: Development Framework for Indonesiaʼs Economic Transformation; Ministry of National Development Planning: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rizky, M. KKP Targetkan Produksi Perikanan Capai 30,37 Juta Ton di 2023; CNBC Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20230221114342-4-415606/kkp-targetkan-produksi-perikanan-capai-3037-juta-ton-di-2023 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Sari, D.A.A.; Muslimah, S. Blue economy policy for sustainable fisheries in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 423, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Regional Initiative on Blue Growth|FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1238765/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Damanik, R. Proyek Strategis Ekonomi Biru Menuju Negara Maju 2045 Penulis Asisten Penulis; Laboratorium: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on the Blue Economy. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations. ASEAN.org. 2021. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/4.-ASEAN-Leaders-Declaration-on-the-Blue-Economy-Final.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Medina, D.; Enggriyeni, D. Implementation of the Blue Economy Concept in Sustainable Development of Indonesian Oceans (International Law and National Law Perspectives). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Interdisciplinary Conference on Environmental Sciences and Sustainable Developments (IICESSD) 2022, Palu, Indonesia, 7–8 November 2022; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Addamo, A.M.; Calvo Santos, A.; Guillén, J.; Neehus, S.; Peralta Baptista, A.; Quatrini, S.; Telsnig, T.; Petrucco, G. The EU Blue Economy Report 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Mumbai, India, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambodo, L.A.A.T. (Ed.) Indonesia Blue Economy Roadmap; Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Darajati, M.R. Ekonomi Biru: Peluang Implementasi Regulasi Di Indonesia. J. Soc. Gov. 2023, 4, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, B.; Rudiman, G.; Pardede, A.A.; Khaddafi, M. Implementation of Blue Economy as an Alternative for Sustainable Development Financing. Int. Conf. Health Sci. Green Econ. Educ. Rev. Technol. 2023, 5, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, M. The Potential and Challenges of the Blue Economy in Supporting Economic Growth in Indonesia: Literature Review. J. Budg. Isu Dan Masal. Keuang. Negara 2022, 7, 340–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zulkifli, R.; Ozora, E.; Ramadhan, M.A.; Kacaribu, J.P.; Mahendra, R. Indonesia’s Blue Economy Initiative: Oceans as the New Frontier of Economic Development. J. Perdagang. Int. 2023, 1, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprilia; Mulyanie, E. Implementasi Konsep Blue Economy di Indonesia sebagai Upaya Mewujudkan Sutainable Development Goals (SDgs) 14: Life Below Water. J. Ilm. Samudra Akuatika 2023, 7, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudge, M.; Ogier, E.; Alexander, K.A. Marine and coastal places: Wellbeing in a blue economy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 144, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaszuk, T. The European Union (EU) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—Fields for Cooperation and Convergence of Interests in the Blue Economy in the Twenty-First Century. In The South China Sea: The Geo-Political Epicenter of the Indo-Pacific? Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, B.; Wu, D.; Zhang, C.; Xie, W.; Mahmood, M.A.; Ali, Q. How Can the Blue Economy Contribute to Inclusive Growth and Ecosystem Resources in Asia? A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, R.N. Blue economy in Southeast Asia: Oceans as the new frontier of economic development. Marit. Aff. J. Natl. Marit. Found. India 2016, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hananto, P.W.H.; Trihastuti, N.; Prananda, R.R.; Pratama, A.A.; Rahayu, H.E.P. The Challenge of Blue Economy in ASEAN 2023: Climate Change and Regional Security. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1270, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A. Navigating Sustainable Development in ASEAN: A Comprehensive Review of the Blue Economy’s Essential Questions. BIO Web. Conf. 2023, 70, 06004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A.; Wahyudi, H. A Dataset Development for ASEAN’s Blue Economic Posture: Measuring Southeast Asian Countries Capacities and Capabilities on Harnessing the Ocean Economy. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1148, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayuda, R. Strategi Pengembangan Konsep Blue Economy Dalam Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Di Wilayah Pesisir. Indones. J. Int. Relat. 2020, 3, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Riding the Blue Wave: Applying the Blue Economy Approach to World Bank Operations; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099655003182224941/P16729802d9ba60170940500fc7f7d02655 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Febriani, R.; Hamdi, I. Soft Power and Hegemony: Gramsci, Nye, and Cox’s Perspectives. J. Filsafat 2024, 34, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humas DJPT. KKP Bawa Program Ekonomi Biru pada Sidang COFI ke-36; Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024; Available online: https://kkp.go.id/djpt/kkp-bawa-program-ekonomi-biru-pada-sidang-cofi-ke-36/detail.html (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Putra, B.A. Indonesia’s Leadership Role in ASEAN: History and Future Prospects. IJASOS-Int. E-J. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2015, 1, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McCarthy, D.R. The meaning of materiality: Reconsidering the materialism of Gramscian IR. Rev. Int. Stud. 2011, 37, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.W. Gramsci, Hegemony and International Relations: An Essay in Method. Millenn. J. Int. Stud. 1983, 12, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KKP. Produksi Perikanan, Statistik KKP. Available online: https://statistik.kkp.go.id/home.php?m=prod_ikan_prov#panel-footer-kpda (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Al-Haq, F.A. Sekretariat Kabinet Republik Indonesia|Indonesia Matters: Emerging Market to Economic Powerhouse. Sekretariat Kabinet. Available online: https://setkab.go.id/indonesia-matters-emerging-market-to-economic-powerhouse/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Julianto, F.; Rafitrandi, D.; Damuri, Y.R. Advancing Indonesia’s Blue Economy Agenda. CSIS Commentaries. April 2024. Available online: https://www.csis.or.id/publication/advancing-indonesias-blue-economy-agenda/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- OECD. Sustainable Ocean for All Series: Sustainable Ocean Economy Country Diagnostics of Indonesia; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/04/sustainable-ocean-economy-country-diagnostics-of-indonesia_289b179e/9bc36234-en.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kemensetneg, H. Presiden Apresiasi Kinerja Satgas Pemberantasan Pencurian Ikan di Perairan Indonesia; Kementerian Sekretariat Negara RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 29 June 2016; Available online: https://setneg.go.id/baca/index/presiden_apresiasi_kinerja_satgas_pemberantasan_pencurian_ikan_di_perairan_indonesia (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Leni, W. Atasi Illegal Fishing, KKP Kembangkan Pengawasan Berbasis Intelijen; Kontan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024; Available online: https://nasional.kontan.co.id/news/atasi-illegal-fishing-kkp-kembangkan-pengawasan-berbasis-intelijen (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Center, T.H. ASEAN BRIEFS Outlook on Indonesia’s Chairmanship in ASEAN: Will China’s Charm Offensive Undermine Consensus-Building Under ASEAN? 2022. Available online: https://www.habibiecenter.or.id/img/publication/a0b387ff652b2adc2c6627de61d96e67.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Emmers, R. Indonesia’s role in ASEAN: A case of incomplete and sectorial leadership. Pac. Rev. 2014, 27, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KLHK. Indonesia Tunjukkan Kepemimpinan dalam Pengelolaan Lingkungan dan Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim di Pertemuan G20 EDM-CSWG; Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 20 June 2022; Available online: https://ppid.menlhk.go.id/berita/siaran-pers/6594/indonesia-tunjukkan-kepemimpinan-dalam-pengelolaan-lingkungan-dan-pengendalian-perubahan-iklim-di-pertemuan-g20-edm-cswg (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- BAPPENAS. HLF MSP 2024: Indonesia Dorong Ekonomi Biru sebagai Sumber Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Inklusif dan Berkelanjutan; BAPPENAS: Jakarta, Indonesia, 4 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wiradji, S. Blue economy bodes well for ASEAN. The Jakarta Post. 5 July 2023. Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/business/2023/07/05/blue-economy-bodes-well-for-asean.html (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Sari, N.H.; Indrayani, I. The Impact of the ASEAN Way and We Feeling Concepts on Indonesia’s Involvement in Strengthening Regionalism. NEGREI Acad. J. Law Gov. 2022, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemensos. Getting to know The ASEAN Way; Ministry of Social Affairs Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 4 September 2023; Available online: https://kemensos.go.id/en/getting-to-know-the-asean-way (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kausikan, B. ASEAN’s Commitment to Consensus. Australian Institute of International Affairs. Available online: https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/aseans-commitment-to-consensus/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Pradana, R.A.; Darmawan, W.B. Indonesia-ASEAN Institutional Roles and Challenges in the Crisis of the Liberal Order. Intermestic J. Int. Stud. 2023, 7, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemenko PMK. Presiden Joko Widodo Buka KTT ASEAN Ke-43; Kementerian Koordinator Bidang Pembangunan Manusia dan Kebudayaan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 5 September 2023; Available online: https://www.kemenkopmk.go.id/presiden-joko-widodo-buka-ktt-asean-ke-43 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Siborutorop, J. Indonesia’s 2023 ASEAN Chairmanship: Challenges and Policies Taken. J. Ilmu Sos. Indones. 2024, 5, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, F. Chairmanship in ASEAN: Lesson Learned for Indonesia. J. Penelit. Polit. 2022, 19, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERIA. ASEAN Blue Economy Forum 2023: Harnessing Blue Potential for Sustainable Development; ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 4 July 2023; Available online: https://www.eria.org/news-and-views/asean-blue-economy-forum-2023-harnessing-blue-potential-for-sustainable-development (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Setkab, H. Para Pemimpin ASEAN Apresiasi Capaian Keketuaan Indonesia di Tengah Situasi Sulit; Sekretariat Kabinet RI: Jakarta, Indonesia, 3 September 2023; Available online: https://setkab.go.id/para-pemimpin-asean-apresiasi-capaian-keketuaan-indonesia-di-tengah-situasi-sulit/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia. Pidato Pembukaan Yang Mulia Joko Widodo Presiden Republik Indonesia KTT Ke-1 AIS Forum; Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 11 October 2023; Available online: https://kemlu.go.id/publikasi/pidato/pidato-presiden/pidato-pembukaan-yang-mulia-joko-widodo-presiden-republik-indonesia--ktt-ke-1-ais-forum?type=publication (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia. Pidato Pembukaan Yang Mulia Joko Widodo Presiden Republik Indonesia Pertemuan Pemimpin ASEAN dengan Dewan Penasihat Bisnis ASEAN (ABAC); Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://kemlu.go.id/publikasi/pidato/pidato-presiden/pidato-pembukaan-yang-mulia-joko-widodo-presiden-republik-indonesia-pertemuan-pemimpin-asean-dengan-dewan-penasihat-bisnis-asean-(abac)?type=publication (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- BAPPENAS RI. ASEAN Blue Economy Forum 2023. YouTube. 3 July 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRnSJmWis3o (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia. Pidato Pembukaan Yang Mulia Joko Widodo Presiden Republik Indonesia Pada Sesi Pleno KTT ke-43 ASEAN; Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 5 September 2023; Available online: https://kemlu.go.id/publikasi/pidato/pidato-presiden/pidato-pembukaan-yang-mulia-joko-widodo-presiden-republik-indonesia-pada-sesi-pleno-ktt-ke-43-asean?type=publication (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ASEAN. ASEAN Maritime Outlook First Edition Catalogue-in-Publication Data; ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: www.asean.org (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia. Pidato Pembukaan Yang Mulia Presiden Joko Widodo ASEAN Leaders’ Interface with ASEAN Inter-Parliamentary Assembly; Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 10 May 2023; Available online: https://kemlu.go.id/publikasi/pidato/pidato-presiden/pidato-pembukaan-yang-mulia-presiden-joko-widodo-asean-leaders%E2%80%99-interface-with-asean-inter-parliamentary-assembly?type=publication (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia. Pidato Penutupan Yang Mulia Joko Widodo Presiden Republik Indonesia pada KTT Ke-43 ASEAN; Kementerian Luar Negeri Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 7 September 2023; Available online: https://kemlu.go.id/publikasi/pidato/pidato-presiden/pidato-penutupan-yang-mulia-joko-widodo-presiden-republik-indonesia-pada-ktt-ke-43-asean?type=publication (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ASEAN. The 22nd Meeting of the Asean Economic Community Council, Jakarta, Indonesia, 7 May 2023. ASEAN Secretariat. 2023. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Chairs-Media-Statement-AECC22-as-of-7-May-rv_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Bappenas RI. ASEAN Blue Economy Forum 2023 Highlights. YouTube. 13 July 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GJYQFsDusps (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ASEAN. Chairman’s Statement of the 43rd ASEAN Summit, Jakarta, Indonesia, 5 September 2023. ASEAN Secretariat. 2023. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/CHAIRMAN-STATEMENT-OF-THE-43RD-ASEAN-SUMMIT-FIN.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Okamoto, S. Celebrating the World Fisheries Da-Driving Innovation in Sustainable Fisheries in Southeast Asia. United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://www.undp.org/indonesia/blog/celebrating-world-fisheries-day-driving-innovation-sustainable-fisheries-southeast-asia (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Silva, C.; Unlocking Innovative Solutions for Blue Economy Development in Timor-Leste. UNDP. 30 April 2024. Available online: https://www.undp.org/timor-leste/press-releases/unlocking-innovative-solutions-blue-economy-development-timor-leste (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ARISE. Navigating Prosperity: Indonesia’s Blue Economy Roadmap Sails Towards Sustainable Growth and Marine Preservation for Current and Future Generations; ARISE+ Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 21 August 2023; Available online: https://ariseplus-indonesia.org/en/activities/perspectives/navigating-prosperity-indonesia-blue-economy-roadmap-sails-towards-sustainable-growth-and-marine-preservation-for-current-and-future-generations (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ERIA. The Development of ASEAN Blue Economy Framework. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia; ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 20 March 2020; Available online: https://www.eria.org/multimedia/unclassified/the-development-of-asean-blue-economy-framework# (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Hadiwinata, M. Indonesia: Beyond the Blue Economy; International Collective in Support of Fishworkers (ICSF): Chennai, India, 2024; Available online: https://icsf.net/samudra/indonesia-blue-economy-beyond-the-blue-economy/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Santoso, A. Bappenas expects blue economy road map to foster cooperation. Antara News. 4 July 2023. Available online: https://en.antaranews.com/news/287046/bappenas-expects-blue-economy-road-map-to-foster-cooperation (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ordoñez, J.V.D. Blue Economy Bill Passed. BusinessWorld Publishing. 19 August 2024. Available online: https://www.bworldonline.com/the-nation/2024/08/19/614980/blue-economy-bill-passed/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Senate of the Philippines. Senate Approves Blue Economy Act. Senate of the Philippines 19th Congress. 19 August 2024. Available online: https://legacy.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2024/0819_prib1.asp (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- MIMA. Initial Workshop on National Blue Economy Blueprint Development: Setting the Pathway for Malaysia; Maritime Institute of Malaysia (MIMA): Jakarta, Indonesia, 26 December 2023. Available online: https://www.mima.gov.my/news/initial-workshop-on-national-blue-economy-blueprint-development-setting-the-pathway-for-malaysia (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Mohamed, H.H. Blue Economy: Striking A Balance Between Economy and Ocean Conservation. Bernama Malaysian National News Agency. 23 December 2024. Available online: https://www.bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2376177 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- The National Assembly of Vietnam. Resolution National Marine Spatial Planning for the Period of 2021–2030 with a Vision Towards 2050. THƯ VIỆN PHÁP LUẬT. 28 June 2024. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Tai-nguyen-Moi-truong/Resolution-139-2024-QH15-National-marine-spatial-planning-for-the-period-of-2021-2030-623947.aspx# (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- UNDP. Charting the Course: 12 Lessons Drawn from Viet Nam’s Marine Spatial Planning Process; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 24 February 2025; Available online: https://www.undp.org/vietnam/publications/charting-course-12-lessons-drawn-viet-nams-marine-spatial-planning-process (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Viet Nam News. Blue Economy–the Gateway to Sustainable Development for Việt Nam. Viet Nam News. 10 April 2024. Available online: https://vietnamnews.vn/society/1653598/blue-economy-the-gateway-to-sustainable-development-for-viet-nam.html (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Poch, K.; Oum, S. Sustainable Blue Economy Development in Cambodia: Status, Challenges, and Priorities; Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2 August 2023; Available online: https://www.eria.org/research/sustainable-blue-economy-development-in-cambodia-status-challenges-and-priorities (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Brunei Darussalam–Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area. Working Together to Develop an Inclusive Blue Economy. Brunei Darussalam–Indonesia–Malaysia–Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA). 25 June 2024. Available online: https://bimp-eaga.asia/article/working-together-develop-inclusive-blue-economy (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kamis, A. The Blue Economy in Brunei Darussalam; Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://www.eria.org/uploads/The-Blue-Economy-in-Brunei-Darussalam.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ADB. A Road Map for Scaling Up Private Sector Financing for the Blue Economy in Thailand: Investment Report; Asian Development Bank (ADB): Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2023; Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/road-map-private-sector-financing-blue-economy-thailand (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ramli, I.M.; Waskitho, T. Blue Economy Initiatives in South-East Asia: Challenges and Opportunities; Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://www.eria.org/uploads/Blue-Economy-Initiatives-in-South-East-Asia.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- ASEAN. ASEAN Senior Officials Convened for the Inaugural Meeting of the ASEAN Coordinating Task Force on Blue Economy; The ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 11 August 2024; Available online: https://asean.org/asean-senior-officials-convened-for-the-inaugural-meeting-of-the-asean-coordinating-task-force-on-blue-economy/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).