Abstract

The measurement of national well-being has become central to both academic and policy debates, particularly within the framework of sustainable development. In this context, this study investigates the relationship between macroeconomic conditions and subjective well-being in Portugal. Using annual data from 2004 to 2022, we explore the effects of GDP per capita, unemployment, and inflation on the Global Well-Being Index (GWBI). Employing ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, the results indicate a significant positive relationship between GDP per capita and subjective well-being, while inflation is negatively associated. Contrary to expectations, the unemployment rate showed a positive and significant association with the GWBI. This counterintuitive result may reflect institutional buffering effects, such as social safety nets, strong family structures, or lagged responses in perceptions of well-being. Similar patterns were observed in other southern European countries with strong informal social support systems. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how economic indicators relate to perceived well-being, particularly in the context of a southern European country. The study offers relevant insights for public policy, including the alignment of macroeconomic management with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

1. Introduction

The growing interest in measuring national well-being beyond traditional economic indicators reflects a broader shift in development paradigms. Although indicators such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) remain fundamental to macroeconomic assessment, their limitations in capturing quality of life and subjective well-being have been widely recognised. This has led to the increasing integration of well-being indicators into policy agendas, particularly within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which call for more holistic approaches to economic and social progress.

Portugal presents a relevant case for analysing the macroeconomic determinants of subjective well-being. Over the last two decades, the country has experienced considerable economic volatility, marked by periods of crisis, austerity, and gradual recovery. These fluctuations have affected employment, price stability, and income levels—factors known to influence well-being. However, the extent to which these macroeconomic variables affect subjective perceptions of quality of life in the Portuguese context remains largely unexplored in the empirical literature.

This study aims to assess how GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and inflation influence subjective well-being in Portugal, as measured by the Global Well-Being Index (GWBI). The GWBI is a multidimensional index that captures material living conditions and quality of life in various domains.

The analysis is based on annual data from 2004 to 2022 and uses multiple linear regression to estimate the relationship between selected macroeconomic indicators and the GWBI. Diagnostic tests were applied to ensure the robustness of the model and evaluate its statistical assumptions.

The article is organised as follows: Section 2 presents a relationship between the theoretical background and the definition of the study hypotheses; Section 3 describes the data and analysis methods used; Section 4 discusses the results; Section 5 reflects on the conclusions in light of the literature and policy implications; and Section 6 concludes with a summary, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

In recent decades, the ability of macroeconomic conditions to affect the subjective well-being of populations has attracted growing interest. Traditional economic indicators, such as GDP, unemployment, and inflation, have proven insufficient to fully capture citizens’ quality of life, leading to the inclusion of subjective well-being metrics in sustainability agendas. Understanding the links between economic performance and subjective well-being is essential to promoting social sustainability and achieving the goals set by the UN’s 2030 Agenda [1]. In this context, the analysis of national well-being has gained importance in academic and political circles, with numerous studies investigating economic, social, and institutional factors [2].

The relationship between macroeconomic variables and well-being has been widely studied, revealing complex dynamics. Economic indicators such as GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and inflation rate are traditionally considered key metrics for assessing a country’s economic health and, by extension, the well-being of households and individuals. The analysis can also focus on the combined effect of the macroeconomic variables selected for the study of national well-being. Several studies have analysed various countries and concluded that, although GDP per capita and unemployment significantly influence well-being, the impact and importance of inflation are less consistent, suggesting that the impact of inflation on well-being may be influenced by other factors, such as the effectiveness of monetary policy or social support measures [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Per capita GDP is often used as an indicator of economic prosperity and standard of living. Recent studies have qualified the relationship between these variables. Stevenson and Wolfers [9] challenged the Easterlin Paradox (1974), which argues that once a certain level of income is exceeded, well-being does not increase with higher incomes, concluding that increases in GDP per capita do not always generate well-being on a national scale. Stiglitz, Sen, and Fitoussi [10] question the adequacy of GDP as an indicator of social progress, advocating multidimensional approaches. Similarly, Layard et al. [11] concluded that GDP per capita influences well-being, but at decreasing levels. This implies that, although increases in GDP per capita lead to increases in well-being, the incremental well-being obtained for each additional unit of income decreases as income levels increase. Stevenson and Wolfers [9] show that there is a positive relationship between GDP per capita and levels of well-being, even over longer periods, arguing that economic growth brings improvements in public services (education and health) or infrastructure, which contributes to well-being. In addition, several authors have concluded that in countries with higher GDP per capita, individuals report emotional well-being, associating economic prosperity with well-being [12,13,14,15,16].

The literature supports a positive relationship between GDP per capita and well-being [17,18,19,20,21,22]. Blanchflower [21] states that the relationship seems to be particularly strong in less developed countries, while in more developed economies there are diminishing returns. In the Portuguese context, research indicates a positive short-term relationship between income and well-being [20]. However, Welsch and Kühling [18] mention that GDP growth can have negative effects in specific circumstances, suggesting that the relationship may be more complex than initially assumed and potentially dependent on other economic and social factors. In this context, we aim to assess whether GDP per capita has a positive influence on the Global Well-Being Index (H1).

On the other hand, the relationship between unemployment and well-being has been characterised by more direct negative correlations [23,24]. Clark and Oswald [25] concluded that unemployment seriously reduces well-being, regardless of the effects of income. This reduction in well-being is attributed not only to loss of income, but also to loss of confidence in the economy and social and psychological impacts on society [26]. Knabe and Rätzel [27] assess the psychological costs associated with unemployment, with the impact going beyond the immediate loss of income, increasing the loss of self-esteem and unhappiness during unemployment. Helliwell and Huang [28] confirm that unemployment not only reduces well-being due to the loss of income but also has an impact on the creation of social stigma and mental health problems, especially in periods of high unemployment rates. Winkelmann and Winkelmann [29] investigate why unemployment leads to unhappiness, associating it with effects beyond the loss of income. These relationships are confirmed by Di Tella et al. [30] who explain that the psychological impact of unemployment goes beyond unemployed individuals, infecting and affecting the well-being of society in general, increasing fear and insecurity about the potential loss of employment and reducing the overall well-being index of a population.

The negative relationship between unemployment and well-being is strongly supported in the literature [18,21,22,31,32]. The magnitude of this effect is major, with studies indicating that the negative impact of unemployment is approximately 2.5 to 5 times stronger than that of inflation [31,32]. Welsch and Kühling [18] point out that unemployment exacerbates the negative impact of GDP decline on well-being. However, Rasiah et al. [19] point out contradictions, with some OECD countries showing a positive relationship, suggesting potential contextual factors that are worth considering. From the literature review, it is established that the unemployment rate negatively influences the Global Well-Being Index (H2).

Finally, inflation represents another economic variable with a complex influence on well-being. Easterlin [33] discusses broader economic conditions on society’s level of well-being beyond income, arguing that inflation can affect well-being indirectly by destabilising economic conditions and reducing real income and overall life satisfaction. Stutzer and Meier [34] evaluate how macroeconomic instability, for example, caused by a high inflation rate, can influence individual household decision-making and condition their well-being and decrease personal well-being. Therefore, inflation decreases purchasing power, affecting lower income households more and contributing to income inequality in the nation, showing a negative correlation with national well-being [35,36,37].

Several authors show a negative relationship between inflation and well-being [19,21,31,32]. However, the impact of inflation is consistently found to be weaker than that of unemployment [21,31,32]. Welsch and Kühling [18] suggest that the effect of inflation is neutral or weak, and Marton and Mojsejová [17] find no significant relationship. The data indicate that the impact of inflation is too weak to offset the negative effects of other economic factors, such as declining GDP and unemployment [18]. Thus, the inflation rate, especially when it is high, tends to have a negative influence on the Global Well-Being Index (H3).

Recent studies have increasingly highlighted the importance of integrating subjective well-being into national sustainability frameworks [38,39,40]. This integration allows for more holistic assessments of progress, aligning economic goals with societal well-being. In this context, analysing macroeconomic indicators through the lens of sustainable development has gained traction in policy and academic discourse. GDP per capita has a positive correlation with well-being, while the effects of unemployment and inflation are predominantly negative. This study aims to quantify the influence of key macroeconomic indicators on national well-being, offering insights into how economic growth strategies can be aligned with improvements in quality of life.

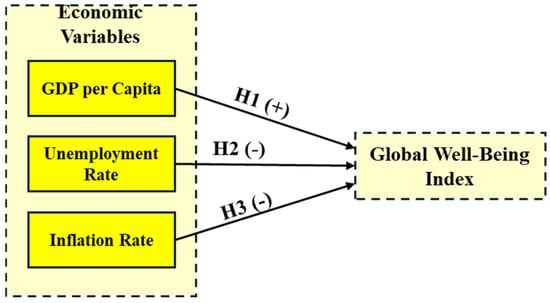

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed theoretical model, highlighting the expected relationships between the economic variables and the GWBI, explaining the theoretical directions of the relationships studied.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework. Source: Figure created by authors.

3. Materials and Methods

This study aims to assess the relationship between key economic indicators (GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and inflation rate) and national well-being, as measured by the GWBI in Portugal. The dependent variable is the Global Well-Being Index (GWBI), which reflects the evolution of the population’s well-being and is composed of “material living conditions” and “quality of life”, with Portugal’s value calculated based on a relative comparison with European reference countries for the period in question [41]. The index is broken down into different domains such as economic well-being; economic vulnerability; work and pay; health; work–life balance; education, knowledge and skills; social relations and subjective well-being; civic participation and governance; personal security; and the environment [41].

The independent variables included GDP per capita (in euros), the unemployment rate (percentage of the total labour force), and the inflation rate (annual percentage change in consumer prices). The study uses a quantitative methodology to examine the impact of selected macroeconomic indicators—GDP per capita, unemployment rate and inflation rate—on the Global Well-Being Index (GWBI) in Portugal from 2004 to 2022. This time interval was selected due to the availability of annual data on all variables, representing the only continuous period in which harmonised and validated data are accessible for the selected indicators. The data were collected from PORDATA, a statistical database with high methodological robustness that consolidates official national statistics from the National Statistics Institute (INE) and international statistics from Eurostat or the World Bank. All data series were standardised to annual values and checked for missing values and outliers using visual inspection and descriptive statistics. No imputation was needed.

To assess relationships, a multiple linear regression model was used, estimated with Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) [42]. Before model estimation, the time series were tested for stationarity using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. Diagnostic checks were performed, including variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis to detect multicollinearity and the Durbin–Watson statistic to assess autocorrelation. All variables were stationary, with VIF values well below the critical threshold of 5 and a Durbin–Watson value of 1.54 indicating moderate autocorrelation. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted for all statistical tests.

At the same time, to explore the associations between the GWBI and the selected economic indicators, a multiple regression analysis was performed to assess the unique contribution of each economic indicator in explaining the variation in well-being scores by evaluating the relative importance of each economic indicator on well-being, adjusting for intercorrelations between the independent variables. The regression model will be specified as follows:

Well-BeingIndext = β0 + β1(GDPpercapitat) + β2(UnemploymentRatet) + β3(InflationRatet) + Ɛt, where β0 is the intercept; β1, β2, β3 are the coefficients for GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and inflation rate, respectively; and Ɛt represents the error term. In addition, tests were carried out to assess the stationarity of the time series (ADF), residual autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson), and potential multicollinearity problems (VIF), the results of which are discussed in the Section 4.

Given the small sample size (n = 19), the choice of OLS was guided by its robustness in small-sample contexts and comparability with similar single-country studies. However, we acknowledge that the results should be interpreted with caution due to limited degrees of freedom. As the analysis is exploratory and based on a single-country time series, the findings should be interpreted as contextual patterns rather than generalised causal inferences.

To ensure the reliability of the regression model, standard diagnostic tests were performed. Unit root tests using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) method were applied to all time series. Residual diagnostics included the Anderson–Darling test for normality, the White test for heteroskedasticity, and the Durbin–Watson statistic for autocorrelation. All results are reported in Appendix A.

4. Results

This analysis aims to assess the association among the defined economic variables (GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and inflation rate) and the level of satisfaction and well-being of Portuguese society, measured by the GWBI, to confirm or refute the hypotheses previously defined. To analyse these hypotheses, data on the variables was used for the period between 2004 and 2022, as this is when the GWBI became available annually.

Table 1 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between the Global Well-Being Index (GWBI) and the selected macroeconomic indicators.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix between GDP per capita, unemployment rate, and inflation rate with GWBI for Portugal.

The linear regression model explains a significant proportion of the variation in the GWBI. As shown in Table 2, the model’s coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.7604) and adjusted R2 (0.7108) indicate good explanatory power, with a relatively low standard error (0.2251).

Table 2.

Model regression analysis.

The overall significance of the model is confirmed by the ANOVA results (Table 3). The F-statistic of 15.87 (p < 0.001) validates that the set of independent variables collectively explains variation in well-being.

Table 3.

ANOVA Table.

Table 4 displays the estimated regression coefficients. GDP per capita has a strong and statistically significant positive effect on the GWBI (β = 0.0095; p < 0.01). The coefficient for GDP per capita (0.0095) implies that an increase in income per person is associated with a 0.95-point increase in the GWBI, all else being held constant. Inflation is negatively associated with well-being (β = −1.42737; p < 0.05). The unemployment rate also shows a statistically significant positive coefficient (p < 0.05), which is unexpected and may reflect contextual factors such as institutional support or lag effects (β = 0.78381; p = 0.0327). This result suggests that the unemployment variable may not exert a consistent influence, possibly reflecting social support mechanisms or lags in perception.

Table 4.

Regression coefficients.

These findings collectively suggest that macroeconomic conditions—particularly income levels and inflation—are significant determinants of subjective well-being in Portugal. Regression analysis reveals a strong and statistically significant positive relationship between GDP per capita and the GWBI, indicating that increases in national income are associated with higher levels of perceived well-being.

As expected, inflation has a statistically significant negative coefficient, reinforcing its adverse effect on well-being. Surprisingly, the unemployment rate is positively and significantly associated with the GWBI (β = 0.7838; p = 0.033), a counterintuitive result that may reflect the influence of contextual factors such as social safety nets, institutional buffers, or delayed impacts on subjective perceptions.

The model explains 76.0% of the variation in the well-being index (R2 = 0.760) and 71.2% when adjusted for degrees of freedom (adjusted R2 = 0.712), which represents major explanatory power given the limited number of predictors. No multicollinearity problems were detected (VIF values: GDP = 2.00; unemployment = 1.80; inflation = 1.18), and the Durbin–Watson statistic of 1.54 indicates moderate positive autocorrelation—common in macroeconomic series—although not at a level that compromises the reliability of the model estimates (Table 5).

Table 5.

Model diagnostics summary.

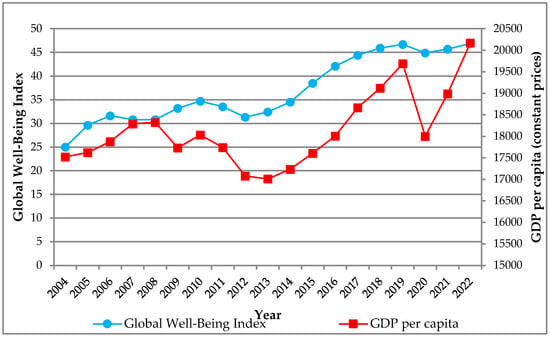

To visually support the statistical conclusions, Figure 2 shows the evolution of the GWBI and GDP per capita over time, showing a generally parallel trend and suggesting an inverse dynamic with inflation. These patterns are explored in more detail in the subsequent discussion.

Figure 2.

Index of GDP per capita and Global Well-Being Index in Portugal (2004–2022). Source: Author’s own calculations using data from PORDATA.

5. Discussion

The empirical results confirm the relevance of macroeconomic indicators as determinants of subjective well-being in Portugal. The validation of Hypothesis 1 reinforces the theoretical proposition that economic growth—measured by GDP per capita—has a strong and positive influence on the quality of life perceived by citizens. This conclusion is consistent with a vast body of literature suggesting that higher income levels improve access to resources, services, and opportunities, all of which are essential for life satisfaction and social sustainability [9,30].

Hypothesis 2, which predicted a negative relationship between unemployment and well-being, was not confirmed. In fact, the unemployment coefficient appears to be positive and statistically significant. This unexpected result may reflect the moderating role of specific sociocultural and institutional factors in the Portuguese context, such as strong family ties, informal support networks, and state-funded social protection mechanisms. These elements may mitigate the negative psychological and material consequences normally associated with unemployment. Previous research in southern European countries has observed similar buffering effects [43,44].

Hypothesis 3 is validated, confirming that inflation has a negative and statistically significant effect on well-being. Inflation tends to erode purchasing power, generate financial uncertainty, and reduce future expectations, which in turn can contribute to stress and dissatisfaction. This result is consistent with the idea that macroeconomic stability—particularly in terms of price levels—is a critical foundation for sustainable and inclusive development.

These findings suggest that the relationship between economic performance and subjective well-being is subtle and mediated by institutional and cultural contexts. While GDP growth and inflation dynamics behave as expected, the case of unemployment highlights the importance of considering the social infrastructure that interacts with macroeconomic realities [37,38]. Therefore, in the pursuit of social sustainability, policymakers must consider both structural economic factors and informal systems that shape individual and collective resilience.

Thus, according to the analysis carried out with the data collected for Portugal between 2004 and 2022, we can evaluate the hypotheses defined below:

H1.

GDP per capita has a positive influence on the Global Well-Being Index.

The positive relationship between income and society’s well-being and the country’s level of well-being is confirmed.

H2.

The unemployment rate negatively influences the Global Well-Being Index.

This is not confirmed by the data collected. This can be explained by periods of low unemployment rates or by the social support available in the country. These results may reflect a form of institutional cushioning through Portugal’s social security systems, or cultural adaptation mechanisms, identical to the results observed in Southern Europe (e.g., Italy, Spain), where family networks and informal economies mitigate the psychological impacts of unemployment.

H3.

The inflation rate, especially when it is high, has a negative influence on the Global Well-Being Index.

The negative relationship is confirmed by the regression, albeit very weakly, but the Portuguese inflation rates collected are quite low, except for the last year analysed. These findings align with the broader goal of integrating economic and social indicators in the design of sustainable development policies, particularly within Southern European countries sharing similar socio-economic dynamics.

The unexpected positive relationship between unemployment and subjective well-being may seem counterintuitive when contrasted with traditional economic theory, which posits that unemployment reduces individual satisfaction and quality of life. However, this conclusion is consistent with evidence from southern European contexts, where family structures, informal economies, and social protection systems can cushion the negative effects of unemployment. These findings are consistent with data from Italy and Spain, where subjective well-being remains stable even amid high unemployment rates, due to family and institutional buffers [30,40,45,46,47,48]. The Portuguese tradition of multigenerational families with strong support among their members and active social assistance programmes may mitigate the psychological costs of unemployment [49,50]. Furthermore, it is possible that subjective well-being is influenced by expectations and perceptions of social justice, and not just by the current employment situation. For policymakers, the findings suggest that promoting GDP growth must be balanced with macroeconomic stability and reinforced social support mechanisms to sustain population well-being.

6. Conclusions

This study fills a gap in the literature by examining macroeconomic influences on subjective well-being in the Portuguese context, reinforcing the importance of integrating economic and social policies to promote sustainability. By analysing data from Portugal between 2004 and 2022, it provides evidence that GDP per capita is positively associated with well-being, while inflation has a clear negative impact. Although the relationship between unemployment and well-being deviates from theoretical expectations, it underlines the importance of country-specific contexts and social safety nets and the role of public policies in this dynamic.

From a political perspective, these results underscore the need for a more holistic approach to economic planning—one that integrates well-being metrics into national and regional development frameworks. Promoting stable economic growth remains crucial, but equal attention must be given to mitigating the adverse social consequences of economic cycles, particularly through robust social safety nets and proactive employment policies. Policies should not only aim for macroeconomic balance but also improve quality of life through multidimensional strategies based on the principles of social sustainability.

These insights are especially relevant for countries with similar socioeconomic profiles and welfare structures and contribute to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). By integrating subjective well-being into the policy agenda, governments can promote more equitable, inclusive, and sustainable societies.

The article has some limitations, including the short period of time for which data on the variables studied are available (19 years), the small sample size, and the exclusion of institutional or cultural factors. Although the GWBI is a composite indicator, it may obscure specific trends in each domain.

Future research should explore these dynamics through longitudinal or panel data models and expand the scope of analysis to include additional variables such as income inequality, access to healthcare, educational attainment, and trust in institutions. Comparative studies between southern European countries may also offer a richer understanding of how common institutional characteristics influence the interaction between macroeconomic factors and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.T.; methodology, N.T.; software, N.T.; validation, N.T., L.P. and R.V.d.S.; formal analysis, N.T.; investigation, N.T.; resources, N.T.; data curation, N.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.T.; writing—review and editing, L.P. and R.V.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are publicly available and were obtained from the PORDATA database (https://www.pordata.pt/), which compiles official statistics from INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatística) and Eurostat. No individual-level or confidential information was used. As such, the study did not require ethical approval under institutional guidelines. All procedures followed academic standards of integrity and responsible research conduct.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Model Diagnostics

Table A1.

Results of Unit Root Tests (ADF).

Table A1.

Results of Unit Root Tests (ADF).

| Variable | Test Statistic | Critical Value (5%) | p-Value | Stationary at Level? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita | −0.87 | −3.04 | 0.797 | No |

| Unemployment rate | −2.98 | −3.08 | 0.036 | Yes |

| Inflation rate | −2.49 | −3.05 | 0.119 | No |

| GWBI | 3.74 | −3.19 | 1.000 | No |

Note: Tests conducted with intercept only (no trend), using optimal lag length selected via Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Caution is advised due to the limited number of observations (n = 19).

Table A2.

Residual Diagnostics.

Table A2.

Residual Diagnostics.

| Test | Test Statistic | p-Value | Assumption Met? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normality (Anderson–Darling) | 0.392 | 0.344 | Yes |

| Heteroskedasticity (White test) | 9.865 | 0.361 | Yes |

Note: Both tests confirm the adequacy of model assumptions, with no evidence of residual non-normality or heteroscedasticity.

References

- Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 10 May 2025).[Green Version]

- World Happiness Report. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).[Green Version]

- Aral, N.; Bakır, H. A spatial analysis of happiness. Panoeconomicus 2024, 71, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K. Effectuality of Happiness Index; SSRN: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. What can economists learn from happiness research? J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 402–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadjova, V.; Trajkov, A. Basic economic indicators and economic well-being. Horiz. Int. Sci. J. Ser. A Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022, 31, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frijters, P.; Beatton, T. The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 82, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, B.; Wolfers, J. Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox (No. w14282); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Revisited; OFCE: Paris, France, 2009; Volume 33, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Layard, R.; Mayraz, G.; Nickell, S. The marginal utility of income. J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 1846–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Well-Being for Public Policy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, G.; Nandedkar, T.; Kumar, A. Analyzing the Causal Relationship between Selected Macro-Economic Variables and Happiness Index: Empirical Evaluation from Indian Economy. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2023, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bublyk, M.; Feshchyn, V.; Bekirova, L.; Khomuliak, O. Sustainable Development by a Statistical Analysis of Country Rankings by the Population Happiness Level; COLINS: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2022; pp. 817–837. [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis, D.; Sun, Y.; Green, M.; Duncan, P. Does a relationship exist between GLOBE Study Leadership Behaviors and GDP per Capita and Happiness Indicators? Am. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 6, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, B.; Mojsejová, A. Macroeconomic Indicators and Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from the European Union. Stat. Stat. Econ. J. 2022, 102, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. How has the crisis of 2008–2009 affected subjective well-being? Evidence from 25 OECD countries. Bull. Econ. Res. 2016, 68, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasiah, R.R.V.; Habibullah, M.S.; Baharom, A.H. The economic antecedents of human well-being: A pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panel. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 1158–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, H.; Calapez, T.; Porto, C. Does the macroeconomic context influence subjective well-being in Europe and Portugal? The puzzling case of the 2008 crisis. Port. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 13, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchflower, D.G. Is Unemployment More Costly Than Inflation? NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, R.D.; MacCulloch, R.J.; Oswald, A.J. The macroeconomics of happiness. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2003, 85, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.; Dieguez, T.; Nunes, P. How unemployment may impact happiness: A systematic review. In Research Anthology on Macroeconomics and the Achievement of Global Stability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.; Graham, C. The economics of happiness. In Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.E.; Oswald, A.J. Unhappiness and Unemployment. Econ. J. 1994, 104, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. International Happiness: A New View on the Measure of Performance. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabe, A.; Rätzel, S. Quantifying the psychological costs of unemployment: The role of permanent income. Appl. Econ. 2011, 43, 2751–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Huang, H. New measures of the costs of unemployment: Evidence from the subjective well-being of 3.3 million Americans. Econ. Inq. 2014, 52, 1485–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, L.; Winkelmann, R. Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica 1998, 65, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, R.; MacCulloch, R.J.; Oswald, A.J. Preferences over Inflation and Unemployment: Evidence from Surveys of Happiness. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Bell, D.N.; Montagnoli, A.; Moro, M. The happiness trade-off between unemployment and inflation. J. Money Credit Bank. 2014, 46 (Suppl. S2), 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Bell, D.N.; Montagnoli, A.; Moro, M. The Effects of Macroeconomic Shocks on Well-Being; University of Stirling: Stirling, Scotland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A. Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutzer, A.; Meier, A.N. Limited self-control, obesity, and the loss of happiness. Health Econ. 2016, 25, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alesina, A.; Di Tella, R.; MacCulloch, R. Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 2009–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 1359–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, A. The Well-Being Cost of Inflation Inequalities. Rev. Income Wealth 2024, 70, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Duan, H.; Zhuang, M.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, B. Global effects of progress towards Sustainable Development Goals on subjective well-being. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Díaz, R.R.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Castillo, D. Contributions of subjective well-being and good living to the contemporary development of the notion of sustainable human development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voukelatou, V.; Gabrielli, L.; Miliou, I.; Cresci, S.; Sharma, R.; Tesconi, M.; Pappalardo, L. Measuring objective and subjective well-being: Dimensions and data sources. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2021, 11, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estatísticas Sobre Portugal e Europa. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28.0. Computer Software. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021.

- Gedikli, C.; Miraglia, M.; Connolly, S.; Bryan, M.; Watson, D. The relationship between unemployment and wellbeing: An updated meta-analysis of longitudinal evidence. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2023, 32, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Barrington-Leigh, C.P. Measuring and understanding subjective well-being. Can. J. Econ./Rev. Can. D’économique 2010, 43, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, F.; Rosina, A.; Sironi, E. On the changes of the intention to leave the parental home during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison among five European countries. Genus 2021, 77, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro-Egido, A.L.; Navarro, M.; Sánchez, A. Changes in subjective well-being over time: Economic and social resources do matter. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2009–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, P.; Agahi, O.; Beilmann, M.; Bettencourt, L.; Brazienė, R.; Edisherashvili, N.; Keranova, D.; Marta, E.; Milenkova, V.; O’hIggins, N.; et al. Subjective well-being of NEETs and employability: A study of non-urban youths in Spain, Italy, and Portugal. Politics Gov. 2024, 12, 7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, R.; Cárcaba, A.; González, E. Drivers of subjective well-being under different economic scenarios. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casquilho-Martins, I. The impacts of socioeconomic crisis in Portugal on social protection and social work practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleiras, J.; Carmo, R.M. The politics of social policies in Portugal: Different responses in times of crises. Soc. Policy Adm. 2024, 58, 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).