From Values to Action: The Roles of Green Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Eco-Anxiety in Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Italian Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Nuanced Role of Eco-Anxiety

2.2. Green Self-Efficacy

2.3. Green Self-Identity, Eco-Anxiety, Green Self-Efficacy and Pro-Environmental Behaviour

2.4. Biospheric Values

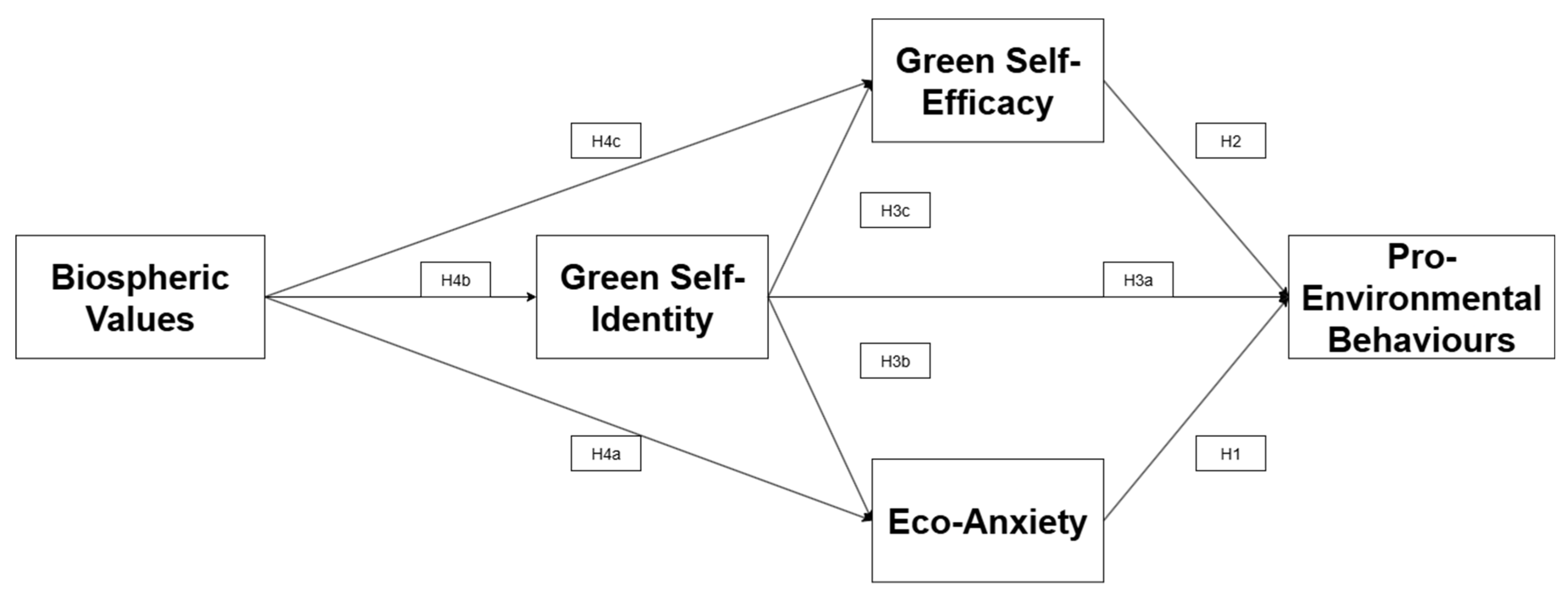

2.5. The Present Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Survey

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.3. Measures

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edo, G.I.; Itoje-akpokiniovo, L.O.; Obasohan, P.; Ikpekoro, V.O.; Samuel, P.O.; Jikah, A.N.; Nosu, L.C.; Ekokotu, H.A.; Ugbune, U.; Oghroro, E.E.A.; et al. Impact of Environmental Pollution from Human Activities on Water, Air Quality and Climate Change. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 874–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-009-15794-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmeier-Young, M.C.; Zhang, X. Human Influence Has Intensified Extreme Precipitation in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13308–13313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, A.; Califano, G.; Caracciolo, F.; Del Giudice, T.; Cembalo, L. Eco-Packaging in Organic Foods: Rational Decisions or Emotional Influences? Org. Agric. 2024, 14, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canova, L.; Capasso, M.; Bianchi, M.; Caso, D. From Motivation to Mediterranean Diet Intention and Behavior: A Combined Self-Determination Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Psychol. Health 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carfora, V.; Caso, D.; Sparks, P.; Conner, M. Moderating effects of pro-environmental self-identity on pro-environmental intentions and behaviour: A multi-behaviour study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Berger, S.; Byrka, K.; Brügger, A.; Henn, L.; Sparks, A.C.; Nielsen, K.S.; Urban, J. Beyond Self-Reports: A Call for More Behavior in Environmental Psychology. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosic, A.; Passafaro, P.; Molinari, M. Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Public Sphere: Comparing the Influence of Social Anxiety, Self-Efficacy, Global Warming Awareness and the NEP. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaludin, J. Pro-Environmental Behavior among University Students: Integrating Norm Activation and Planned Behavior Models. Ecocycles 2025, 11, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurišević, N.; Stojadinović, M.; Končalović, D.; Josijević, M.; Gordić, D. Students’ Perceptions of Air Quality: An Opportunity for More Sustainable Urban Transport in the Medium-Sized University City in the Balkans. Tehnika 2023, 78, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Nguyen, B.; Mutum, D.S.; Yap, S.-F. Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Value-Belief-Norm Theory: Assessing Unobserved Heterogeneity of Two Ethnic Groups. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Watsford, C.R.; Walker, I. Clarifying the Nature of the Association between Eco-Anxiety, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Ying, M.; Mehmood, S.A. The Interplay of Green Servant Leadership, Self-Efficacy, and Intrinsic Motivation in Predicting Employees’ pro-Environmental Behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Buscicchio, G.; Catellani, P. Proenvironmental Self Identity as a Moderator of Psychosocial Predictors in the Purchase of Sustainable Clothing. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquariello, R.; Bianchi, M.; Mari, F.; Caso, D. Fostering Local Seasonality: An Extended Value-Belief-Norm Model to Understand Sustainable Food Choices. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 120, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Yu, G. Media Coverage of Climate Change, Eco-Anxiety and pro-Environmental Behavior: Experimental Evidence and the Resilience Paradox. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 91, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; Blanchard, M.A.; Coussement, C.; Heeren, A. On the Measurement of Climate Change Anxiety: French Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale. Psychol. Belg. 2022, 62, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; der Werff, E.V.; Bouman, T.; Harder, M.K.; Steg, L. I Am vs. We Are: How Biospheric Values and Environmental Identity of Individuals and Groups Can Influence Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 618956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecina, M.L.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; López-García, L.; Díaz-Silveira, C. Eco-Anxiety and Trust in Science in Spain: Two Paths to Connect Climate Change Perceptions and General Willingness for Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnoli, G.M.; Tiano, G.; De Rosa, B. Is Climate Change Worry Fostering Young Italian Adults’ Psychological Distress? An Italian Exploratory Study on the Mediation Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty and Future Anxiety. Climate 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From Anger to Action: Differential Impacts of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Depression, and Eco-Anger on Climate Action and Wellbeing. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavani, J.-B.; Nicolas, L.; Bonetto, E. Eco-Anxiety Motivates pro-Environmental Behaviors: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study. Motiv. Emot. 2023, 47, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Csaba, B.; Nagy, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Dúll, A.; Rácz, J.; Demetrovics, Z. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Effic. Beliefs Adolesc. 2006, 5, 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Y.; Manh, T. Antecedents of Pro-Environmental Behaviors: A Study on Green Consumption in an Emerging Market. Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag. 2022, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menardo, E.; Brondino, M.; Pasini, M. Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Pro-Environmental Behaviours Scale (PEBS). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6907–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Faggi, V.; Castellini, G.; Manelli, I.; Magrini, G.; Galassi, F.; Ricca, V. Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Li, W.; Xiaoguang, L.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Sackey, N. Social Trust, Past Behavior, and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection: Evidence from China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media Use, Environmental Beliefs, Self-Efficacy, and pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.-M. Drivers and Interrelationships of Three Types of Pro-Environmental Behaviors in the Workplace. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1854–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S. Identity Salience and Role Performance: The Relevance of Symbolic Interaction Theory for Family Research. J. Marriage Fam. 1968, 30, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charng, H.-W.; Piliavin, J.A.; Callero, P.L. Role Identity and Reasoned Action in the Prediction of Repeated Behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1988, 51, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The Value of Environmental Self-Identity: The Relationship between Biospheric Values, Environmental Self-Identity and Environmental Preferences, Intentions and Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, E.P.; Carrete, L.; Arroyo, P. A Study of the Antecedents and Effects of Green Self-Identity on Green Behavioral Intentions of Young Adults. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannetti, L.; Pierro, A.; Livi, S. Recycling: Planned and Self-Expressive Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green Identity, Green Living? The Role of pro-Environmental Self-Identity in Determining Consistency across Diverse pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. Positive and Negative Antecedents of Purchasing Eco-Friendly Products: A Comparison Between Green and Non-Green Consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Binder, C.R. Determinants of Different Types of Positive Environmental Behaviors: An Analysis of Public and Private Sphere Actions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, M.; Guidetti, M.; Bianchi, M.; Cavazza, N.; Caso, D. Enhancing Intentions to Reduce Meat Consumption: An Experiment Comparing the Role of Self- and Social pro-Environmental Identities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 101, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M. The Role of Parental Identity in Experiencing Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1579893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nature Relatedness May Play a Protective Role and Contribute to Eco-Distress. Available online: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/epdf/10.1089/eco.2023.0004 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisah, T.; Ernestivita, G.; Kurniawan, A. Towards Sustainable Textile Practices: Exploring the Role of Green Self-Concept and Theory of Planned Behavior in Consumer Behavior. GRENZE Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2025, 10, 2707–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Kosslyn, S.M. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-90077-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wicklund, R.; Gollwitzer, P. Symbolic Self-Completion, Attempted Influence, and Self-Deprecation. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 2, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Czellar, S. Where Do Biospheric Values Come from? A Connectedness to Nature Perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions Predict Policy Support: Why It Matters How People Feel about Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Barnett, J. ‘Will Polar Bears Melt?’ A Qualitative Analysis of Children’s Questions about Climate Change. Public Underst. Sci. 2020, 29, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C.J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S.D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When Worry about Climate Change Leads to Climate Action: How Values, Worry and Personal Responsibility Relate to Various Climate Actions. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating Environmental Concern in the Context of Psychological Adaption to Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, Norms, and Intrinsic Motivation to Act Proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, C.-K. A Moderator of Destination Social Responsibility for Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behaviors in the VIP Model. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaningsih, E.S.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Hamdan, H.; Marlapa, E.; Shiratina, A. Towards Green Behavior: Egoistic And Biospheric Values Enhance Green Self-Identities. J. Manaj. 2023, 27, 449–470. [Google Scholar]

- Azadi, Y.; Yaghoubi, J.; Gholamrezai, S.; Rahimi-Feyzabad, F. Farmers’ Adaptation Behavior to Water Scarcity in Western Iran: Application of the Values-Identity-Personal Norms Model. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.; Van Der Werff, E.; Steg, L. Values at Work: Understanding How Individual and Perceived Organisational Values Relate to Employees’ Motivation and pro-Environmental Behaviour at Work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 103, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Kim, W. Decoding Pro-Environmental Behaviors in China through Values and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Asian J. Public Opin. Res. 2025, 13, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher Westland, J. Lower Bounds on Sample Size in Structural Equation Modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A-Priori Sample Size for Structural Equation Models References—Free Statistics Calculators. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/references.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Curcio, C.; Capasso, M.; Pasquariello, R.; Caso, D.; Donizzetti, A.R. Validation of the Integrated Pro-Environmental Behaviours Scale (I-PEBS). Sustainability 2025, 17, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markle, G.L. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Does It Matter How It’s Measured? Development and Validation of the Pro-Environmental Behavior Scale (PEBS). Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; Cicia, G. Explaining Consumer Purchase Behavior for Organic Milk: Including Trust and Green Self-Identity within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, B.L.; Stahlmann, A.G. Which Character Strengths Are Focused on the Well-Being of Others? Development and Initial Validation of the Environmental Self-Efficacy Scale: Assessing Confidence in Overcoming Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior. J. Well-Being Assess. 2019, 3, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, G.; Pileri, J.; Luciani, F.; Gennaro, A.; Lai, C. Insights into Eco-Anxiety in Italy: Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale, Age and Gender Distribution. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior: How to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To Parcel or Not to Parcel: Exploring the Question, Weighing the Merits. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling and More. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. A General Method for Estimating a Linear Structural Equation System. ETS Res. Bull. Ser. 1970, 1970, i-41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M.C.; Tröger, J.; Hamann, K.R.S.; Loy, L.S.; Reese, G. Anxiety and Climate Change: A Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale in a German-Speaking Quota Sample and an Investigation of Psychological Correlates. Clim. Change 2021, 168, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Lombardi, G.S.; Ciabini, L.; Zjalic, D.; Di Russo, M.; Cadeddu, C. How Can Climate Change Anxiety Induce Both Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Eco-Paralysis? The Mediating Role of General Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Climate Anxiety: Psychological Responses to Climate Change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4192-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R.; Laurenti, R.; Mehdi, T.; Binder, C.R. Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Comparison of University Students and Staff from Diverse Faculties at a Swiss University. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, S.; Schulze Heuling, L. Exploring the role of identity in pro-environmental behavior: Cultural and educational influences on younger generations. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1459165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. Environmental behavior in a private-sphere context: Integrating theories of planned behavior and value belief norm, self-identity and habit. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 148, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-T.; Hsieh, M.-H. Environmental Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, and the Emergence of Green Opinion Leaders: An Exploratory Study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Pro-Environmental Behavior on Electric Vehicle Use Intention: Integrating Value-Belief-Norm Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The Relationship between Corporate Environmental Responsibility, Employees’ Biospheric Values and Pro-Environmental Behaviour at Work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Uggento, A.M.; Piscitelli, A.; Ribecco, N.; Scepi, G. Perceived Climate Change Risk and Global Green Activism among Young People. Stat. Methods Appl. 2023, 32, 1167–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maran, D.A.; Begotti, T. Media Exposure to Climate Change, Anxiety, and Efficacy Beliefs in a Sample of Italian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, K.; Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K.; Ishii, K. Cultural Variability in the Link Between Environmental Concern and Support for Environmental Action. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pro-environmental behaviours | 3.10 (0.50) | 1 | ||||

| 2. Green self-identity | 3.62 (0.82) | 0.58 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. Green self-efficacy | 5.57 (1.73) | 0.48 ** | 0.51 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Eco-anxiety | 1.41 (0.49) | 0.32 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.31 ** | 1 | |

| 5. Biospheric Values | 4.22 (0.72) | 0.38 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.12 ** | 1 |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| β | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eco-Anxiety → Pro-Environmental Behaviours | 0.14 * | 0.13 | [0.01, 0.51] |

| Green Self-Efficacy → Pro-Environmental Behaviours | 0.31 *** | 0.18 | [0.22, 0.84] |

| Green Self-Identity → Pro-Environmental Behaviours | 0.57 *** | 0.21 | [0.62, 1.44] |

| Green Self-Identity → Eco-Anxiety | 0.25 *** | 0.07 | [0.10, 0.40] |

| Biospheric Values → Eco-Anxiety | 0.02 | 0.07 | [−0.11, 0.17] |

| Green Self-Identity → Green Self-Efficacy | 0.48 *** | 0.07 | [0.37, 0.64] |

| Biospheric Values → Green Self-Efficacy | 0.11 * | 0.06 | [0.01, 0.25] |

| Biospheric Values → Green Self-Identity | 0.44 *** | 0.07 | [0.35, 0.62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pasquariello, R.; Donizzetti, A.R.; Curcio, C.; Capasso, M.; Caso, D. From Values to Action: The Roles of Green Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Eco-Anxiety in Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Italian Context. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156838

Pasquariello R, Donizzetti AR, Curcio C, Capasso M, Caso D. From Values to Action: The Roles of Green Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Eco-Anxiety in Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Italian Context. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156838

Chicago/Turabian StylePasquariello, Raffaele, Anna Rosa Donizzetti, Cristina Curcio, Miriam Capasso, and Daniela Caso. 2025. "From Values to Action: The Roles of Green Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Eco-Anxiety in Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Italian Context" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156838

APA StylePasquariello, R., Donizzetti, A. R., Curcio, C., Capasso, M., & Caso, D. (2025). From Values to Action: The Roles of Green Self-Identity, Self-Efficacy, and Eco-Anxiety in Predicting Pro-Environmental Behaviours in the Italian Context. Sustainability, 17(15), 6838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156838