Abstract

This study examined the impact of entrepreneurship education in sustainability on entrepreneurial intention using the theory of planned behavior (TPB). The MEMORE macro was used to analyze within-subject mediation and enabled us to examine how entrepreneurial intention is affected by changes in the factors of the theory of planned behavior (attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control). The survey follows a questionnaire-based, pre-test-post-test design (the research involved 271 business administration students in Athens). A paired sample t-test was used to analyze changes in attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention before and after education. The results indicated that after the entrepreneurship course in sustainability, students indicated a significant positive change in entrepreneurial intention, attitude, and perceived behavioral control. MEMORE macro indicated that only the change in perceived behavioral control positively influenced the increase in entrepreneurial intention levels. Based on these findings, entrepreneurship education in sustainability enhances students’ entrepreneurial intentions by increasing their perceived behavioral control. As a result, students’ confidence and knowledge regarding sustainable entrepreneurship are fundamental to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial mindsets. This study emphasizes the importance of integrating targeted pedagogical approaches that enhance perceived behavioral control in sustainable entrepreneurship education by equipping students with practical knowledge and skills to overcome psychological barriers. The use of the MEMORE macro highlights this study’s innovation, uncovering new relationships between the examined variables.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship research has dedicated substantial attention to studying entrepreneurial intentions [1]. One of the most widely used analytical frameworks in studying entrepreneurial intentions is the theory of planned behavior (TPB). According to this theory, intentions are mainly determined by three key factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Individuals’ decisions regarding entrepreneurial endeavors can be shaped by these three elements. An individual’s attitude toward entrepreneurship can be interpreted as an assessment of whether they believe starting a business is feasible and desirable. Positive attitudes about entrepreneurship are characterized by feelings of personal efficacy and belief in its potential rewards. Subjective norms represent the perceived social pressure to engage or not engage in entrepreneurial activity. An individual’s entrepreneurial ambitions can be influenced by the opinions and expectations of significant others, such as family, friends, and peers [2]. Perceived behavioral control refers to how an individual perceives the ease or difficulty of conducting entrepreneurial behavior. In this context, it refers to one’s ability to overcome obstacles, obtain resources, and overcome the challenges of starting a business [3,4,5].

A factor that enhances entrepreneurial intention and the factors of the theory of planned behavior is entrepreneurship education. In recent years, entrepreneurship education has been examined in relation to its effects on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention: attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Education plays a critical role in shaping individuals’ mindsets, reinforcing positive beliefs about entrepreneurship, and improving perceived entrepreneurial capacities [4,6,7].

The purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of entrepreneurship education in sustainability on entrepreneurial intention by using the theory of planned behavior. In spite of the fact that existing literature acknowledges that entrepreneurship education can positively impact entrepreneurial intentions, studies addressing sustainability education within the theory of planned behavior framework are scant [5]. It is unclear whether the changes in entrepreneurial intention following entrepreneurship education in sustainability are directly related to the shifts in the factors of the theory of planned behavior. While previous studies have acknowledged entrepreneurship education’s positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions, it is not clear whether these changes in intentions are connected to changes in the components of the theory of planned behavior. To address this gap, our research employs a pre-test–post-test design and uses the MEMORE macro in order to gain new insights into the specific mechanisms that promote entrepreneurship through sustainability education.

Based on the purpose of the study, the following research questions are proposed:

- “Does sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education affect students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship?”

- “Does participation in sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education shape students’ perceptions of social expectations and support (i.e., subjective norms)?”

- “Does sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education affect students’ perceived behavioral control in starting a business?”

- “Does sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education affects students’ entrepreneurial intentions?”

- “Does the sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education influence students’ entrepreneurial intentions through its impact on their attitudes, subjective norms, and/or perceived behavioral control”?

Despite the growing emphasis on entrepreneurship as a source of economic development and sustainability, it is imperative for the Greek economy to foster entrepreneurial activity among university graduates. Sustainability should be effectively incorporated into entrepreneurship education as global challenges demand more socially and environmentally conscious solutions. This study contributes both theoretical insight and practical implications for curriculum development in higher education, with particular relevance to enhancing entrepreneurial dynamism in Greece.

2. Theoretical Background

Entrepreneurship has played an important role in economic development and innovation globally, and its role is growing as new ideas and business models reshape industries. In understanding what motivates individuals to pursue entrepreneurial paths, Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior plays an integral role, as it offers a framework for analyzing factors (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) that influence entrepreneurial intentions [8,9]. One of the most influential sources enhancing all of these factors is entrepreneurship education. Education in entrepreneurship is essential for cultivating entrepreneurial intentions and equipping individuals with the tools necessary to navigate the complexities of business [5,6,7,10,11].

In entrepreneurship courses, real-life case studies, simulations, business plan exercises, and guest lectures from successful entrepreneurs demonstrate the relevance and excitement of starting a company. Students who become aware of the value of entrepreneurship, such as job creation, innovation, and personal autonomy, are more likely to develop favorable attitudes toward becoming entrepreneurs themselves [7,10,12,13]. Entrepreneurship education in sustainability increases students’ awareness of environmental and social challenges, and may encourage them to consider entrepreneurship as a way to address issues such as climate change and resource depletion [14,15,16,17]. Values-driven perspectives may further enhance students’ intrinsic motivation and perception of entrepreneurship as a meaningful career path. Entrepreneurship education in sustainability affects attitudes toward sustainable entrepreneurship in a positive way [18].

Several aspects of entrepreneurship education contribute to the positive effect of subjective norms. In the first place, the education system fosters a peer culture that values entrepreneurial behavior by putting students in environments where entrepreneurship is discussed and encouraged, for example, through group projects, incubators, and mentorship programs [2]. Subjective norms are increased when students interact with like-minded peers. Furthermore, education introduces students to mentors—successful entrepreneurs, social innovators, and sustainability leaders—who serve as role models. By exposing students to these figures through classroom activities, networking events, and case studies, they can change their perceptions of what is socially acceptable [7]. As students enter sustainability-focused entrepreneurship programs, they are more likely to meet peers, mentors, and role models who value social and environmental responsibility [14,19]. Entrepreneurial role models can have powerful social influences on students, reinforcing the perception that entrepreneurship is a worthwhile pursuit and is supported by society [2,15]. Sustainability-focused projects strengthen students’ understanding of entrepreneurship’s social value and legitimacy, further strengthening subjective norms [2,20].

Entrepreneurship education has a significant impact on perceived behavioral control, especially in the context of sustainability. An individual’s perception of their ability to engage in entrepreneurial activities is referred to as their perceived behavioral control [7]. Students enrolled in sustainable entrepreneurship courses gain critical knowledge and skills that increase their confidence in launching and managing sustainable businesses. In the entrepreneurship process, students who gain knowledge and understand sustainable practices, such as environmental regulations, green technologies, and social entrepreneurship models, feel more capable of succeeding. Students who are aware of the available resources, including funding options, sustainable business networks, and mentorship opportunities, are more likely to perceive fewer barriers to entrepreneurship and gain the self-confidence they need [14,17]. Acquiring knowledge about sustainable businesses (eco-friendly business models and sustainable supply chains) [7,15] equips students with the skills needed to make informed decisions. This knowledge also fosters a proactive, innovative mindset [21,22], which is essential for addressing the challenges of sustainable entrepreneurship in an ever-evolving landscape [23,24]. When students learn how to conduct business plans, market research, develop financing strategies, navigate real-world obstacles, and understand legal frameworks, they are more likely to think of themselves as able to start their own company [15]. A knowledge-based approach demystifies the entrepreneurial process, reduces uncertainty, and lowers psychological barriers. In knowing the steps involved in starting a business, individuals feel less anxious and more in control [5]. Ultimately, these factors contribute to strengthening students’ entrepreneurial intentions and preparing them for success in sustainable business ventures [7,11,14,15,17].

In this study, the implemented course was focused on entrepreneurship education in sustainability. Entrepreneurship education in sustainability nurtures future leaders who balance profit with environmental responsibility [14,22,25]. The main focus of the course has been on teaching how to think and act like entrepreneurs by developing entrepreneurial knowledge, skills, and mindsets. Through a combination of theory and real-world application, the course cultivated an entrepreneurial mindset for solving sustainability problems. Students learned about entrepreneurial ventures through experiential learning, mentorship, and the analysis of case studies [23,26].

The duration of this course is thirteen weeks. Lessons last three hours per week, with two hours of lectures and one hour of practical deepening. Lectures are focused on theoretical topics, utilizing relevant books, articles, talks by entrepreneurs active in sustainable business practices —such as circular economy models, green technology, and ethical supply chains—as well as CEOs in multinational companies leading sustainability initiatives. As part of the deepening groups, students work in teams to create business plans, applying their knowledge to practice. These actions positively shape students’ subjective norms, influencing how they perceive sustainable business as a social expectation. To enhance the understanding of each educational unit, parallel assignments are prepared. The purpose of the course is to create, through team spirit, a microenvironment that fosters a strong sense of collaboration and a new circle of peers with shared interests and to strengthen students’ business knowledge, skills, and attitudes, with the goal of encouraging entrepreneurial initiatives and entrepreneurial intentions focused on sustainability. As a result of this course, students will be motivated to create their own sustainable businesses, will be equipped with all the critical skills and knowledge to launch their own sustainable ventures, to understand the needs and opportunities of the market, to identify and manage threats, and to think creatively and critically. The educational program aligns with the European Commission’s guidelines for effective entrepreneurship education and constantly adapts to new market data. Educating students in this way strengthens their self-confidence and their ability to operate in business effectively and methodically [27].

In order to understand the complexity of sustainable entrepreneurship, the course placed an emphasis on experiential learning. Students were not only required to take part in lectures but also engaged in immersive activities that mirrored the challenges faced by businesses that are focused on sustainable development [26]. Through business simulations, students were asked to develop solutions to environmental issues (for example, reducing carbon emissions and reducing waste) at the same time as navigating competitive and regulatory pressures. These simulations provide a safe environment to experiment, fail, adapt, and innovate [28].

The sustainability venture creation project provided students with the opportunity to develop mission-driven business ideas. Among these projects were those that focused on solving specific sustainability problems (like food waste, energy inefficiency, or ocean plastic) through the development of scalable, viable business models [20]. Throughout all activities, innovation was a common theme. In this course, students developed an innovation mindset that balanced creativity with feasibility and urgency with long-term impact. A mentorship program supported this process by pairing students with entrepreneurs. Mentorship is widely recognized as a means to improve entrepreneurial confidence and decision making. Their practical advice and real-life insights bridged the gap between theory and application, especially in sustainability-focused ventures [26].

Furthermore, students learned how entrepreneurs are tackling global challenges such as climate change, renewable energy, and circular design through real-world case studies. Case-based learning enhances students’ strategic thinking skills and their understanding of real-world complexity [14,22,26]. The case studies illustrated that ethical, sustainable business is not only possible, but increasingly necessary. Group projects and workshops were all part of the highly interactive learning environment. Guest lectures were performed on emerging trends such as regenerative business models and sustainable digital innovation [20]. Using entrepreneurial tools and environmental insight, the process cultivated both competence and consciousness—preparing the next generation of leaders for complex global challenges through innovative, sustainable ventures [26].

As part of courses on sustainable entrepreneurship, students also learn about green technologies, environmental regulations, sustainable supply chains, and circular economy models. Students are empowered by this specialized knowledge to pursue entrepreneurial ideas aligned with sustainability principles. Due to global issues, entrepreneurship is becoming increasingly challenging, and understanding sustainability and social responsibility helps students feel more confident and capable of becoming entrepreneurs, which improves perceived behavioral control [11,14,17,19,21,22].

Entrepreneurship education in sustainability is effective in cultivating the psychological and cognitive foundations for entrepreneurial behavior. This study examined the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in sustainability using the theory of planned behavior. By gaining theoretical insight, practical experience, and access to real-world resources, students feel more in control of the entrepreneurial process. Having a greater sense of control increases their self-efficacy as well as reduces perceived risks, leading them to form stronger entrepreneurial intentions. The application of knowledge in sustainable entrepreneurship education supports future entrepreneurs in managing complexity, driving innovation, and pursuing profitable ventures that contribute to ethical business practices, protection of the environment, and social impact. In order to prepare students to become confident, competent, and committed entrepreneurs, educators should tailor entrepreneurship education to address all three dimensions of the theory of planned behavior [9].

3. Materials and Methods

This study examined the impact of entrepreneurship education (in sustainability) on entrepreneurial intention, taking into consideration the factors of the theory of planned behavior (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) using quantitative methods. We employed a questionnaire-based approach that used a 7-point Likert scale to capture student attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intentions. A pre-test–post-test design was used to measure these key variables before and after the entrepreneurship course. To establish a baseline for further analysis, participants were asked to complete pre-course questionnaires. After completing the 13-week course, post-course questionnaires (with the same questions as the pre-course questionnaires) were distributed to the students who had completed the pre-course version. The questionnaire used in this study is based on the theory of planned behavior and the entrepreneurial intention framework [29]. It is a validated and widely used instrument that has been directly adopted from previous studies [5,27]. Specifically, 3 items were used to measure attitude toward entrepreneurial intention, 3 items were used for subjective norms, 5 items were used for perceived behavioral control, and 4 items were used for entrepreneurial intention.

A total of 271 students (157 women, 114 men) participated in the study, providing an adequate sample size for statistical analysis. All participants were students at a public university in Athens, enrolled in the business administration department, and had taken the course on Entrepreneurship in Sustainability. Their ages ranged as follows: 256 individuals were between 18 and 24 years old, 6 were between 25 and 34, 5 were between 35 and 44, and 4 were between 44 and 54. The principal component analysis (PCA) method was used to verify the factor structure and ensure data adequacy. Bartlett’s test of sphericity and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measurements were used to verify the suitability of the data. To evaluate the changes in the measured factors, paired sample t-tests were used. As a result of the entrepreneurship course, differences in attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intentions were examined. The MEMORE macro was used to investigate causal relationships between the theory of planned behavior factors and entrepreneurial intentions. This statistical tool analyzes mediation effects, demonstrating whether changes in the theory of planned behavior factors can influence changes in entrepreneurial intention [30]. MEMORE provided a deeper understanding of the causal pathways connecting the independent and dependent variables. This approach provided a better understanding of the impact of education.

Using a combination of PCA, reliability and adequacy testing, t-test, and MEMORE enhanced the validity and reliability of this study. Statistical analysis provided a framework, allowing us to draw conclusions about entrepreneurship education in sustainability and its impact on student outcomes (examined factors). This methodology serves as a strong foundation for understanding the complex interplay between entrepreneurship education in sustainability, the theory of planned behavior, and entrepreneurial intentions.

4. Results

In order to analyze the correlation structure between the examined variables, the principal component analysis (PCA) method was used. The PCA method was chosen because the questionnaires have been extensively examined in previous studies regarding their factor structure and reliability [26,31]. In the questionnaires before and after entrepreneurship education, the KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were used (KMO = 0.880, x2 = 2988, p < 0.01 (for the questionnaire before education), KMO = 0.912, x2 = 2932, p < 0.01 (for the questionnaire after education)) to determine whether the sample data were suitable for further analysis. For the first questionnaire, the principal component analysis retained four components with eigenvalues greater than 1. The first component had an eigenvalue of 6.674, explaining 44.49% of the variance. The second component’s eigenvalue was 2.185, contributing to a cumulative explained variance of 59.06%. The third and fourth components had eigenvalues of 1.783 and 1.026, bringing the total cumulative variance explained to 70.95% and 77.79%, respectively. For the second questionnaire, the analysis identified three principal components that met this criterion. The first component had an eigenvalue of 7.399 and accounted for 49.33% of the variance. The second component had an eigenvalue of 1.841, contributing to a cumulative explained variation of 61.60%. The third component’s eigenvalue was 1.467, bringing the cumulative variance explained to 71.38%. The fourth component had an eigenvalue below 1 (0.805) and was not retained. The weight of each of the four components before and after entrepreneurship education (attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention) is presented in Table 1. The two measurements, before and after entrepreneurship education, were made on the same sample of respondents.

Table 1.

Principal component analysis before and after education.

Cronbach’s Alpha results for each component were above 0.8. More specifically, before education, Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient for attitude was 0.804 (three questions); for subjective norms, it was 0.890 (three questions); for perceived behavioral control, it was 0.876 (five questions); and for entrepreneurial intention, it was 0.950 (four questions). After education, Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient for attitude was 0.817 (three questions); for subjective norms, it was 0.847 (three questions); for perceived behavioral control, it was 0.891 (five questions); and for entrepreneurial intention, it was 0.939 (four questions).

An analysis of a paired samples t-test was used to assess the changes in entrepreneurial intention and the factors of the theory of planned behavior. We examined whether aspects of the respondents changed after learning about entrepreneurship. The results indicated that after the entrepreneurship course in sustainability, there was a positive change in entrepreneurial intention, in perceived behavioral control, and in attitude (Table 2).

Table 2.

Paired samples t-test.

To assess the impact of the course on students’ attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention, a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted. The results indicated a statistically significant improvement in entrepreneurial attitude from pre- to post-course, F(1, 270) = 5.26, p = 0.023, η2 = 0.019, suggesting a small effect size. Descriptive statistics indicated that mean attitude increased from (M = 5.123, SD = 1.111) before the course to (M = 5.244, SD = 1.059) after the course. There was no significant difference between pre-course (M = 5.278, SD = 1.479) and post-course scores (M = 5.269, SD = 1.054), F(1, 270) = 0.009, p = 0.924, η2 = 0.000, indicating that the course did not significantly affect students’ subjective norms. Furthermore, results indicated a significant increase in perceived behavioral control from pre-course (M = 4.010, SD = 1.139) to post-course (M = 4.280, SD = 1.082), F(1, 270) = 23.56, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.080, indicating a moderate effect of the course on students’ perceived behavioral control. Finally, the results indicated a significant increase in entrepreneurial intention from pre-course (M = 4.572, SD = 1.674) to post-course (M = 4.786, SD = 1.499), F(1, 270) = 10.45, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.037, indicating a small to moderate effect of the course on students’ entrepreneurial intentions.

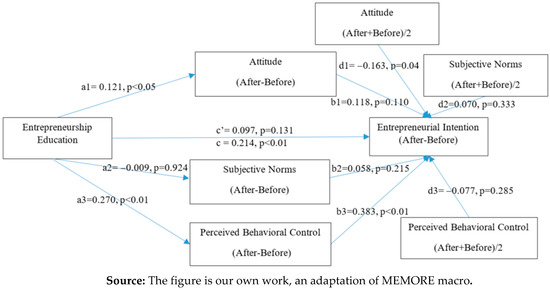

Figure 1 illustrates the statistical model for the effects (direct and indirect) of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention through the changes of the factors (of the theory of planned behavior). The results were exported using the MEMORE macro [30]. According to the following model, entrepreneurship education (x) causes a statistically significant total effect on (y), (entrepreneurial intention), (c = 0.214, p < 0.01) and a direct effect (c′ = 0.097, p = 0.131). According to the above, the total effect matches the paired samples t-test. According to MEMORE, entrepreneurial intention (after–before) is used as the difference scores, and X (predictor) is constant (entrepreneurship education) for all the components. If the predictor does not change, then the total effect is the mean difference, which is precisely what the paired t-test captures.

Figure 1.

MEMORE macro.

It is shown that there is no direct, statically significant change in subjective norms (a2 = −0.009, p = 0.924). However, there are statistically significant and positive changes in attitude (a1 = 0.121, p <0.05) and perceived behavioral control (a3 = 0.270, p <0.01). The change in attitude (b1 = 0.118, p = 0.110) and the change in subjective norms (b2 = 0.058, p = 0.215) did not have a statistically significant direct impact on the change in entrepreneurial intention. On the other hand, the change in perceived behavioral control (b3 = 0.383, p < 0.01) had a statistically significant effect on the change in entrepreneurial intention. Education only has an indirect effect on the change in entrepreneurial intention through the change in perceived behavioral control (a3 * b3 = 0.104, 95% CI [0.056, 0.159]), since the confidence interval does not include 0. The indirect effects of education, through the effect of attitude (a1 * b1 = 0.0142, 95% CI [−0.007, 0.0567]) and the effect of subjective norms (a2 * b2 = −0.0005, 95% CI [−0.017, 0.012]), are not statistically significant, as the confidence interval includes 0 [29,30].

Based on the analysis above, our findings indicate that entrepreneurship education directly affected entrepreneurial intention, attitude, and perceived behavioral control. However, the MEMORE macro indicates that the changes in entrepreneurial intention are only caused by the changes in behavioral control. These findings highlight the novelty of this research, as they indicate that the change in entrepreneurial intention, following an entrepreneurship course, is only caused by a single factor of the theory of planned behavior.

According to these findings, the positive change in perceived behavioral control after the course is crucial to shaping positive entrepreneurial intentions. An individual’s perception of his or her ability to overcome challenges and effectively manage entrepreneurial tasks directly impacts his or her intentions to pursue entrepreneurship. The focus on perceived behavioral control emphasizes the importance of empowering students with the knowledge and skills they need to reduce psychological barriers associated with entrepreneurship, including the fear of failure and uncertainty. Entrepreneurship education programs that enhance students’ perceived behavioral control are likely to have a greater impact on their entrepreneurial intentions.

5. Discussion

In this study, we examined how sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education affects university students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Our approach examined the impact of a structured educational intervention on the psychological drivers of entrepreneurial intentions. The results of the pre-test–post-test study indicated a statistically significant increase in entrepreneurial intention, in attitude toward entrepreneurship, and in perceived behavioral control (PBC) after the course. With the use of the MEMORE macro, this study was able to analyze within-subject mediation across repeated measures. The results indicated that only the positive changes in perceived behavioral control significantly affected the positive change in entrepreneurial intention after the course. The intervention (education) targeted the core components of the theory of planned behavior. The results indicated that the course provided both knowledge and practical experience in sustainability-focused entrepreneurship, which reduced students’ uncertainty and enhanced their confidence in their entrepreneurial skills. This psychological reinforcement explains the significant positive change in perceived behavioral control, which in turn affected the increase in entrepreneurial intention. As a result of real-life case studies, exposure to successful sustainable entrepreneurs, and collaborative business planning, students were able to envision themselves in a variety of entrepreneurial roles. Through direct engagement with sustainable business principles such as the circular economy, ethical production, and green innovation, students can contextualize abstract knowledge and internalize it as actionable sets. Through this experiential learning approach, they were able to enhance their understanding as well as their sense of competence and control over entrepreneurial decisions [5,26].

Furthermore, a positive change in students’ attitudes was observed. The course brought out the social value of sustainable entrepreneurship, the ethical dimension of innovation, and the long-term benefits of responsible business, which likely led to this change. Students learned that entrepreneurship could contribute to solving environmental and social problems, as well as being a valuable economic activity. In this way, entrepreneurship was reframed as a career path aimed at achieving a purpose, which led to more positive evaluations and a stronger sense of emotional engagement with entrepreneurship. Consequently, key entrepreneurial variables improved statistically significantly as a result of addressing cognitive (knowledge-based) and emotional (confidence, motivation) factors [5,26].

The educational intervention did not significantly change subjective norms, probably because it was influenced by individual-level determinants of intention, for example, knowledge acquisition, skill development, and perceptions of self-efficacy, but not perceived expectations or approval of others. The results indicated that students’ social reference groups were not directly engaged by the course, and existing societal expectations regarding entrepreneurship were not actively challenged. As part of improving subjective norms, entrepreneurship education should engage more students’ social context by including more distinguished mentors, guest speakers, and respected entrepreneurs. A business idea presentation or pitch event that involves peers, family, or the community can enhance perceived social support. It is also important to emphasize the societal value of entrepreneurship, especially in sustainability, in order to reinforce social support and value for such paths [26].

Entrepreneurial intention was not significantly influenced by improved attitudes toward entrepreneurship. The change in attitude was minimal, which may help explain why it did not significantly influence entrepreneurial intention. The change in perceived behavioral control (PBC) directly influences the change in intention after the course [26]. The results support the idea that perceived behavioral control plays a key role in influencing entrepreneurial intention through education. Perceived behavioral control incorporates both self-efficacy and perceived ease or difficulty of starting a business, suggesting that students gained practical knowledge and skills to reduce psychological barriers [5,24]. Sustainable entrepreneurship education prepares students not only to succeed in today’s markets but also to contribute to societal progress. Innovative approaches to addressing ecological and social challenges may require the development of entrepreneurs who are capable and committed to sustainability [18,32].

6. Conclusions

Sustainable entrepreneurship education is a topic of increasing interest in the entrepreneurship education community [11,18]. According to our findings, university-level courses focused on sustainable entrepreneurship can significantly improve students’ entrepreneurial intentions, attitudes toward entrepreneurship, and perceived behavioral control [5]. The MEMORE macro provided robust empirical evidence that increased perceived behavioral control after the course affected entrepreneurial intention change. Students’ self-perceptions play a crucial role in determining their entrepreneurial ambitions. Through knowledge, tools, and exposure to sustainable-driven entrepreneurial challenges, students gain confidence and perceived capability that will help to turn intentions into action. The course not only raised awareness about sustainability and entrepreneurship but also enhanced students’ belief in their own agency and readiness to engage in entrepreneurial activities [14].

Despite their academic nature, these findings have broader implications. Educators and policymakers need to recognize sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education as a strategic and effective framework for equipping students with valuable skills for the unstable future [24]. In a world that is focused on sustainability, it is essential to equip students with the mindset, skills, and confidence to lead innovative solutions. It is important to incorporate sustainability principles into entrepreneurship education in order to prepare graduates to contribute meaningfully to economic, social, and environmental well-being [32]. According to the findings of this study, curriculum designers and educators should consider key factors when developing entrepreneurship education programs in sustainability. In particular, the course significantly improved students’ entrepreneurial attitude, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intentions, but not their subjective norms. It is important to note that only changes in perceived behavioral control were significantly associated with increases in entrepreneurial intention. In order to strengthen students’ perception of their ability to manage and control entrepreneurial behavior, entrepreneurship programs should emphasize building these skills.

A variety of practical experiences can enhance perceived behavioral control, including team-based business plans, simulations, and mentorship from successful, sustainable entrepreneurs. A community engagement strategy beyond the classroom environment may be required to influence subjective norms. It is therefore important that institutions that aim to reproduce this course emphasize curriculum features that develop students’ skills and confidence in entrepreneurial action, as these are critical drivers of entrepreneurial intent and, ultimately, sustainable innovation [27].

A longitudinal study of sustainability entrepreneurship education would be beneficial in the future. It would help examine whether increased entrepreneurial intentions and perceived behavioral control lead to actual entrepreneurial activity or influence career choices. Furthermore, comparative studies exploring different pedagogical approaches (e.g., experiential learning, project-based work, and mentoring integration) could shed light on effective teaching methods for sustainability in entrepreneurship education. Additionally, we did not explore possible subgroup differences, such as gender or prior entrepreneurial exposure or working experience, that might moderate the effects of sustainability-focused entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions. In this study, it is important to note that we examine entrepreneurial intention, not real behavior. Our evaluation is based on self-reported perceptions, so we do not have objective data that indicate what leads to subsequent entrepreneurial actions or career progression. No further differentiation was made regarding the sample based on additional demographic or background information, such as the participants’ prior entrepreneurial experience, their previous fields of study, or their socioeconomic background. Such details could provide a more nuanced perspective on the observed effects. This study was conducted at a specific public university in Athens within a particular department. The findings might not be generalizable to students at other universities, in other countries, or in other academic disciplines. To improve the validity and reliability of the results, it may be possible to improve the methodological approach. Expanding the sample size would enhance the statistical power of the study and improve generalizability. A broader and more diverse sample would enhance the robustness of our results.

A more comprehensive understanding of how and why these educational experiences shape entrepreneurial outcomes could be gained by investigating the interplay between other psychological and contextual mediators, such as opportunity recognition, environmental consciousness, and emotional engagement. Overall, this study confirms the transformative potential of sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship education. Boosting the psychological factors of students and their entrepreneurial intentions, such programs foster the next generation of entrepreneurs who are both capable and committed to shaping a more sustainable and equitable world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; methodology, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; software, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; validation, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; formal analysis, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; investigation, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; resources, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; data curation, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; writing—review and editing, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; visualization, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; supervision, A.G.S.; project administration, P.A.T. and A.G.S.; funding acquisition, P.A.T. and A.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is exempt from ethical review due to its anonymous, risk-free, and educational nature, as determined by the Institutional Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all identifiable human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sahinidis, A.G.; Tsaknis, P.A.; Gkika, E.; Stavroulakis, D. The Influence of the Big Five Personality Traits and Risk Aversion on Entrepreneurial Intention. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Kavoura, A., Kefallonitis, E., Theodoridis, P., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustofa, A.; Murtini, W.; Sawiji, H. Effect of Subjective Norms Mediation to Entrepreneurship Intention at Entrepreneurship Learning in School. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2018, 5, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashari, H.; Abbas, I.; Abdul-Talib, A.N.; Mohd Zamani, S.N. Entrepreneurship and sustainable development goals: A multigroup analysis of the moderating effects of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability 2021, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P.A.; Sahinidis, A.G.; Kavoura, A.; Kiriakidis, S. The Differential Effects of Personality Traits and Risk Aversion on Entrepreneurial Intention Following an Entrepreneurship Course. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; McNally, J.J.; Kay, M.J. Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneur-ship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in pre-dicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.B.; Stimpson, D.V.; Huefner, J.C.; Hunt, H.K. An attitude approach to the predic-tion of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship. Theory Pract. 1991, 15, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, H.; Fanea-Ivanovici, M.; Sarango-Lalangui, P. The influence of sustainability education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 390–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G., Jr. Toward a theory of entrepreneurial careers. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1995, 19, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahrani, A.A. Promoting sustainable entrepreneurship in training and education: The role of entrepreneurial culture. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 963549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresch, D.; Harms, R.; Kailer, N.; Wimmer-Wurm, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Techno-Log. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Trancoso, T. The green seed: The influence of pro-sustainable orientation on social entrepreneurship in higher education students. Ind. High. Educ. 2024. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Babar, M.; Mehmood, H.S.; Xie, R.; Guo, G. The environmental values play a role in the development of green entrepreneurship to achieve sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomski, V.G.; Tavares de Souza Junior, A.V.; Lavarda, C.E.F.; Simão Kaveski, I.D.; Slomski, V.; Frois de Carvalho, R.; Fontes de Souza Vasconcelos, A.L. Environmental factors, personal factors, and the entrepreneurial intentions of university students from the perspective of the theory of planned behavior: Contributions to a sustainable vision of entrepreneurship in the business area. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, N.; Mahmood, N.; Mehmood, H.S.; Rashid, O.; Liren, A. The integrated role of personal values and theory of planned behavior to form a sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, F.; Jones, O.; Jayawarna, D. Promoting sustainable development: The role of entrepreneurship education. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 841–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploum, L.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Omta, O. Toward a validity framework for entrepreneurship competence: Bridging the gap between entrepreneurial and sustainable entrepreneurship competence. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, T.; Blok, V.; Wesselink, R. Learning apart and together: Towards an integrated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Hulsink, W. Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, A.; Marques, C.; Ferreira, J.J. The role of entrepreneurship education and training pro-grammes in advancing entrepreneurial skills and new ventures. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D. The sustainable entrepreneur: Balancing people, planet and profit. Entrep. Innov. Exch. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, L. Entrepreneurship education and sustainable development goals: A literature review and a closer look at fragile states and technology-enabled approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P. Shaping Entrepreneurial Intention: The Role of Personality and University Entrepreneurship Programs. A Comparative Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of West Attica, Aigaleo, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D. Entrepreneurship: From Opportunity to Action; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and Cross–Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.K. Moderation analysis in two-instance repeated measures designs: Probing methods and multiple moderator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 9781529630008. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq, M.I.; Sarwar, H.; Aftab, J.; Franzoni, S.; Raza, A. Accomplishing sustainable performance through leaders’ competencies, green entrepreneurial orientation, and innovation in an emerging economy: Moderating role of institutional support. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).