Intergenerational Differences in the Perception of the Assumptions of Individual Organizational Management Models in the Context of Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Promoting mental health and well-being (goal 3.4),

- Promoting sustainable development, a culture of peace, and non-violence (goal 4.7),

- Ensuring decent work, especially for young people and people with disabilities (goal 8.5),

- Ensuring equal pay for work of equal value (goal 8.5),

- Protecting labor rights (goal 8.8),

- Promoting safe working environments, especially for migrants and people in precarious employment (goal 8.8),

- Promoting and strengthening the inclusion of all people, regardless of age, gender, disability, race, ethnic origin, nationality, religion, economic status, or other factors (goal 10.2),

- Reducing violence in all its forms (goal 16.1),

- Ensuring flexible, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making processes at all levels (goal 16.7).

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Organizational Management Models

2.2. Gerational Cohorts in the Labor Market

3. Materials and Methods

- Identification of the level of work experience in organizations representing the management models distinguished by Laloux among generational cohorts currently active in the labor market.

- Verifying the dependency between work experience in organizations representing the distinguished management models and generational cohort affiliation.

- Identifying factors that define the human-centered direction of change in organizational management, based on the personal experiences of generational cohorts currently active in the labor market.

- Evaluation of specific characteristics of the distinguished organizational management models by generational cohorts currently active in the labor market, and projection for Generation Alpha to forecast trends.

- Conducting a test of dependency between the rating of the distinguished organizational management models and generational cohort affiliation.

- Conducting a test of dependency between the rating of specific characteristics of the distinguished organizational management models and generational cohort affiliation.

- Preparing a summary of generationally dependent characteristics based on test results, presented by generational cohort.

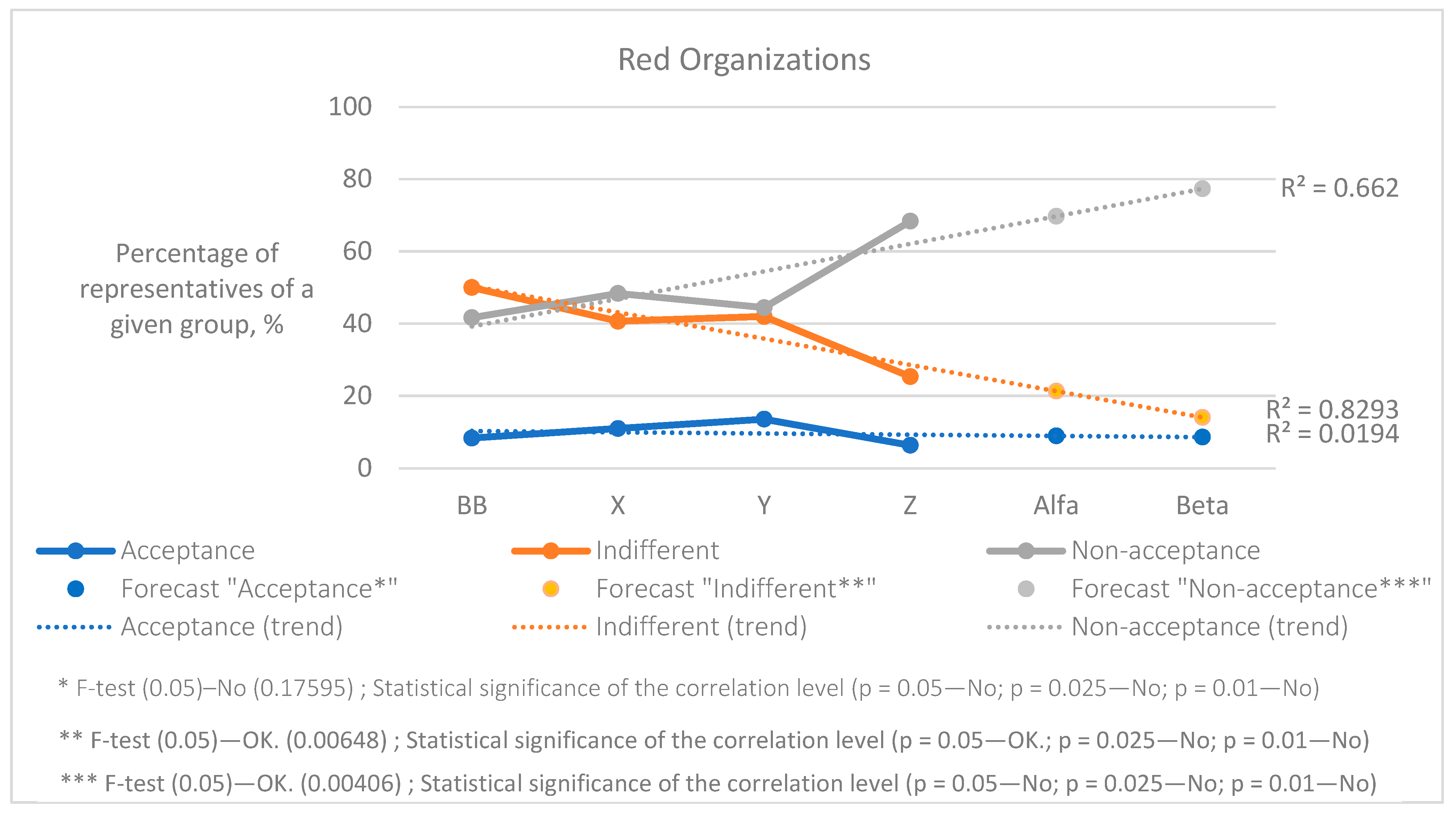

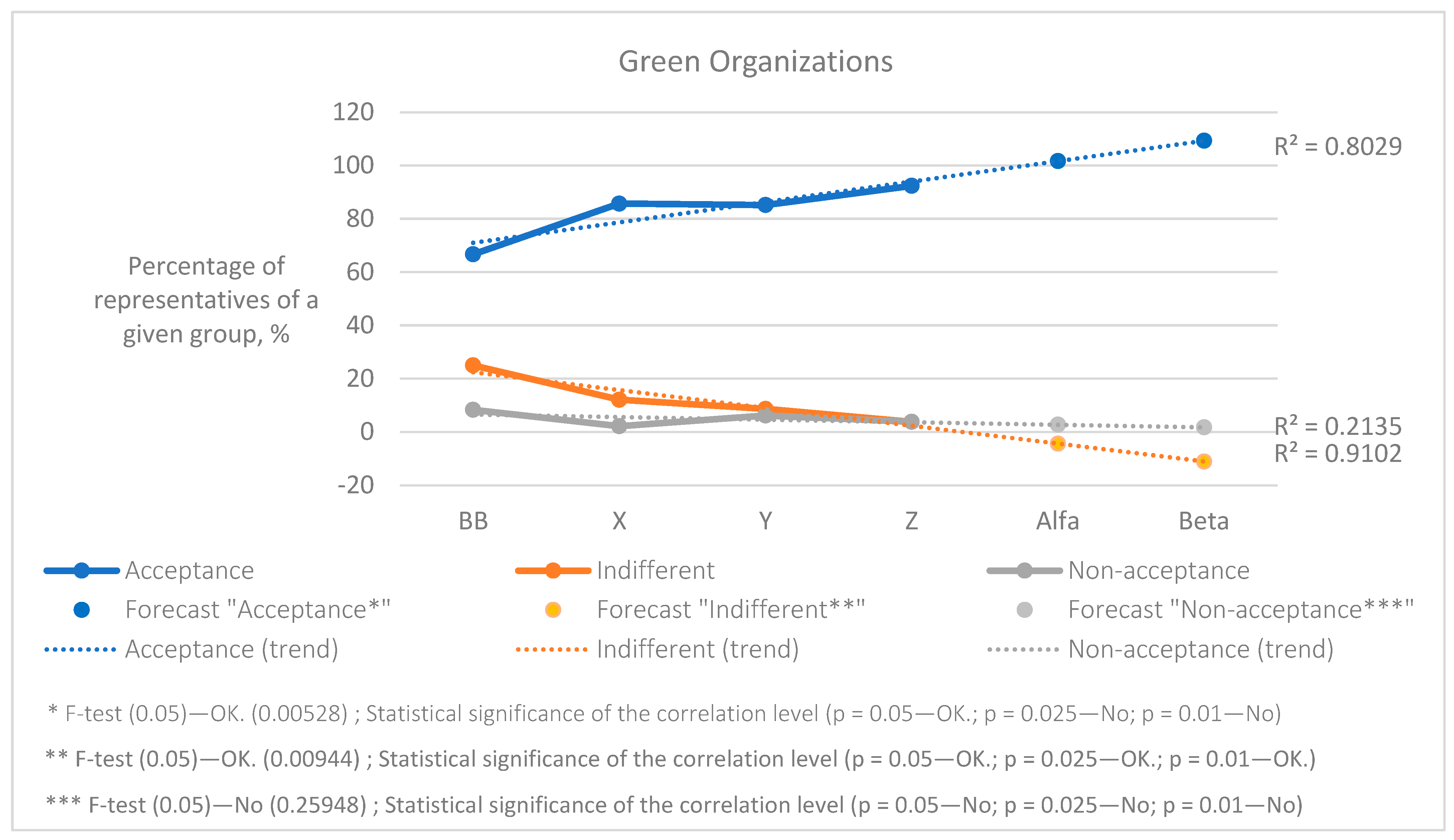

- Determining the level of acceptance of organizational management models that support the concept of sustainable development among employees currently active in the labor market.

- Identifying trends in the acceptance of organizational management models that support the concept of sustainable development among employees currently active in the labor market.

4. Results

4.1. Work Experience

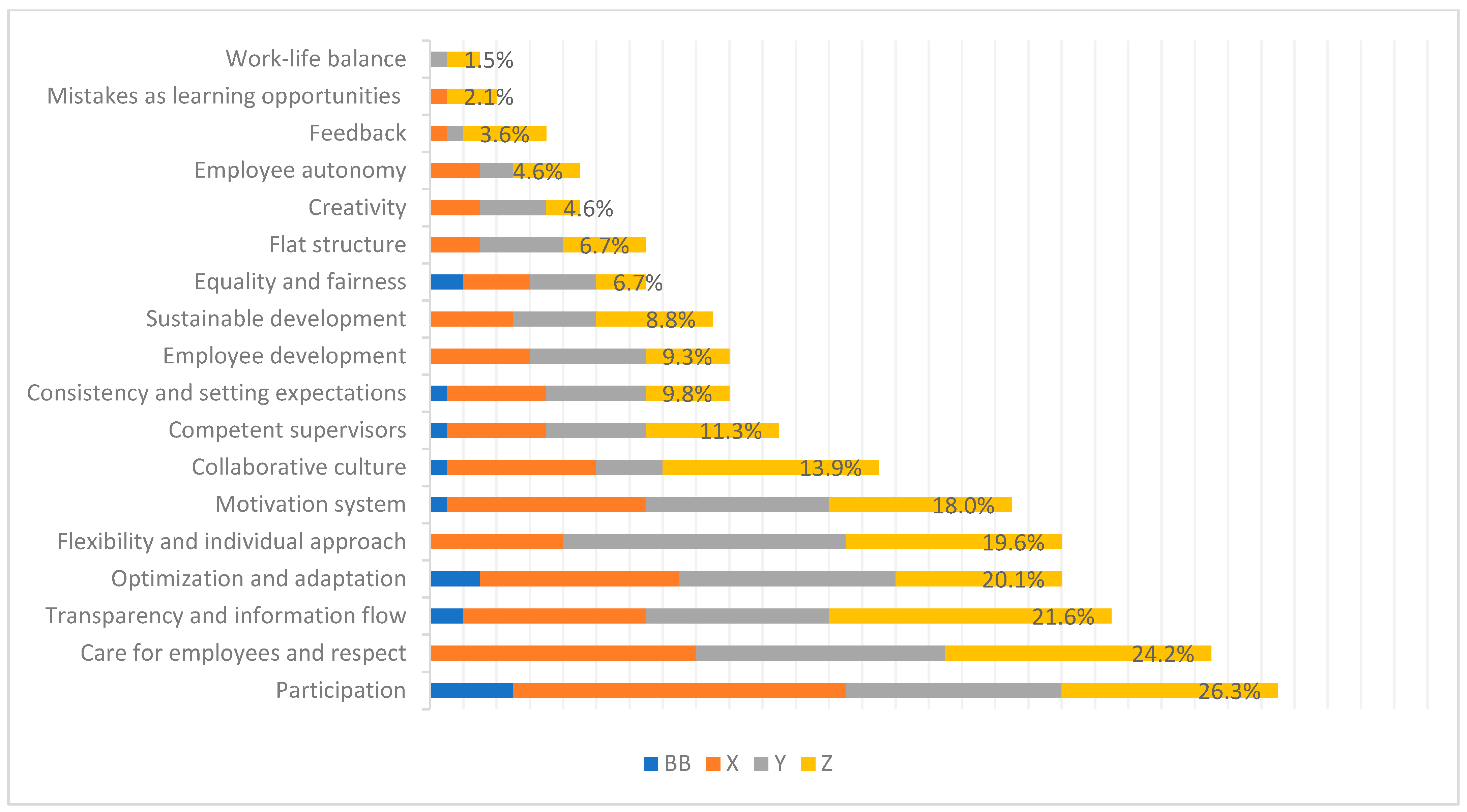

4.2. Proposed Changes in Management Styles

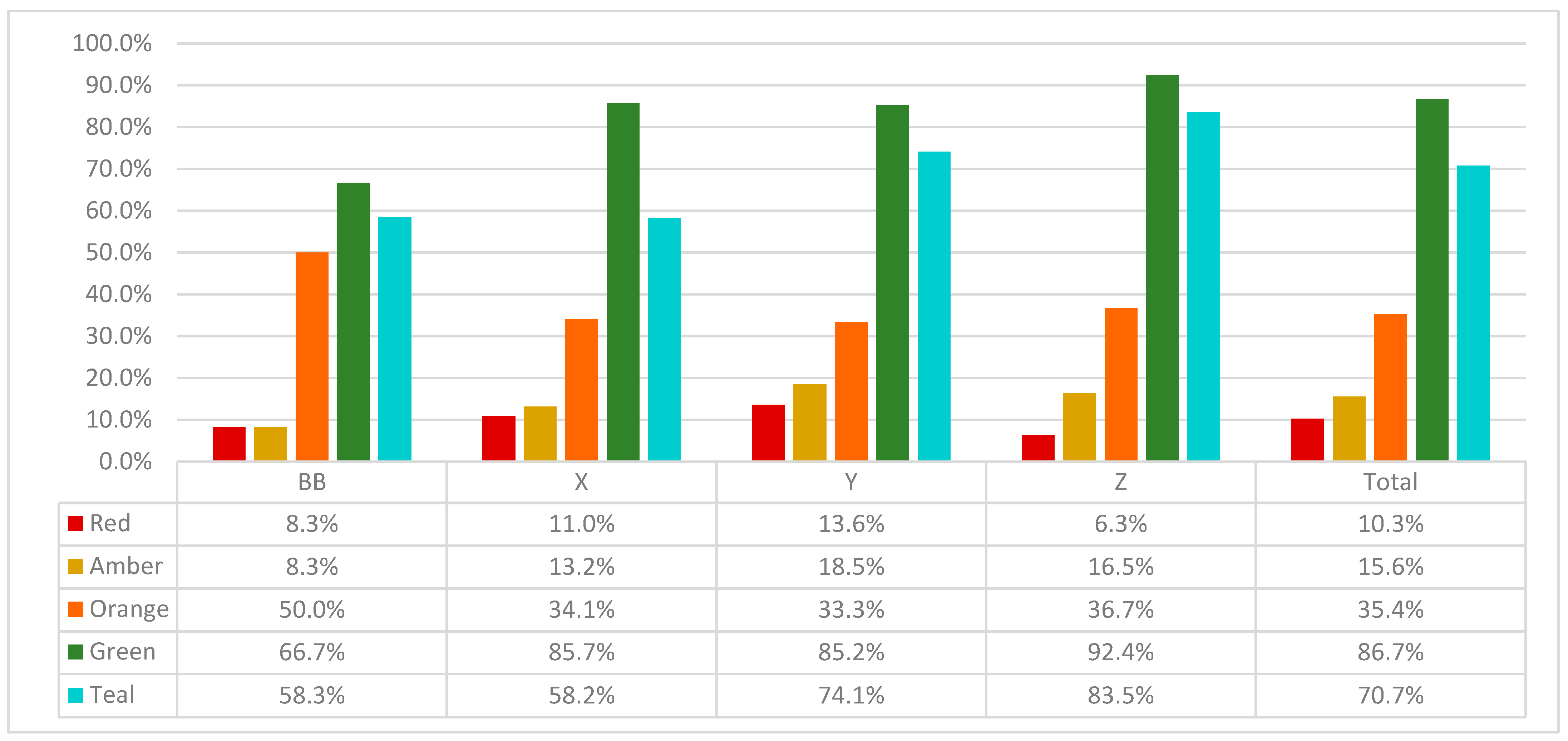

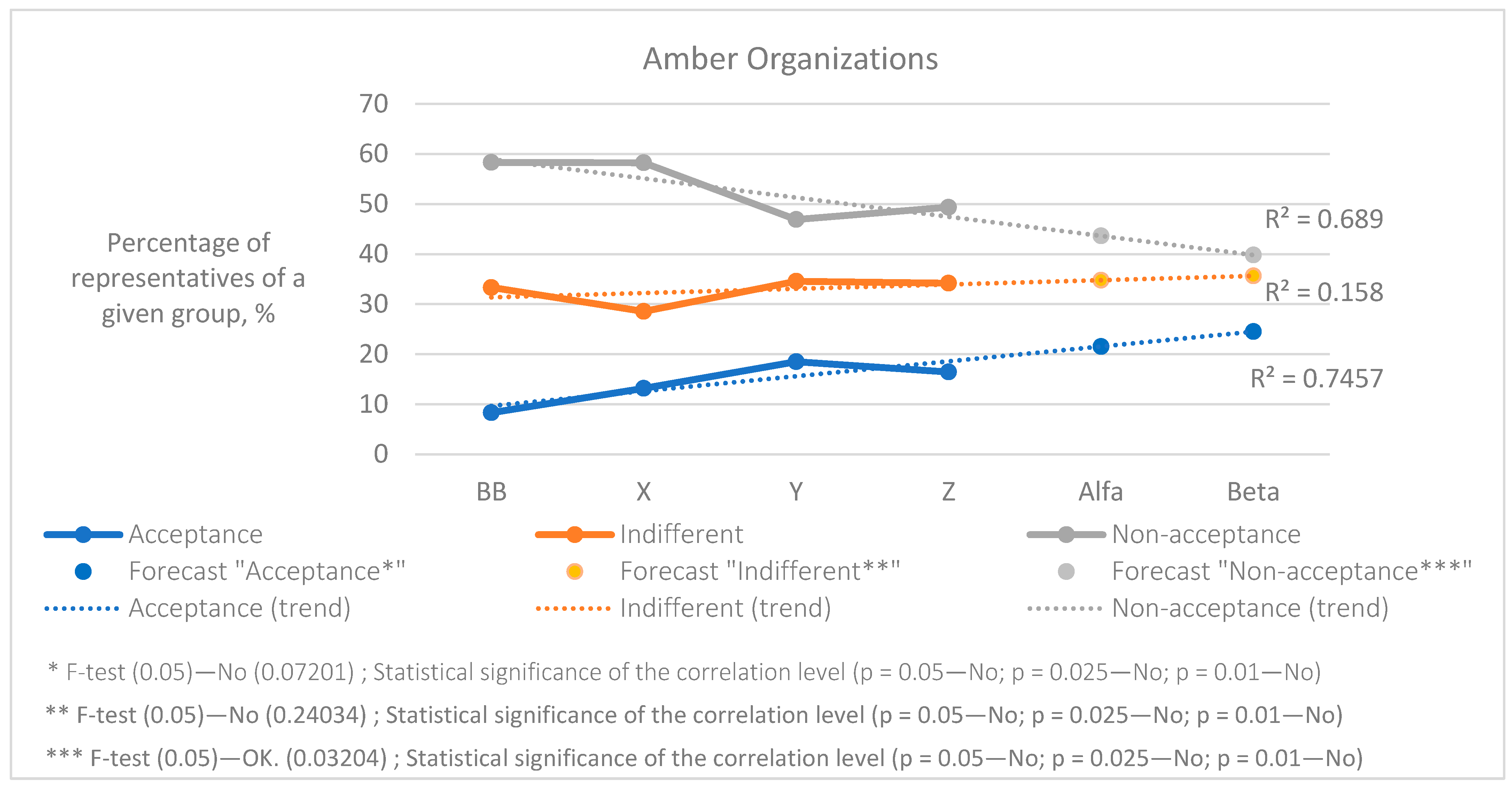

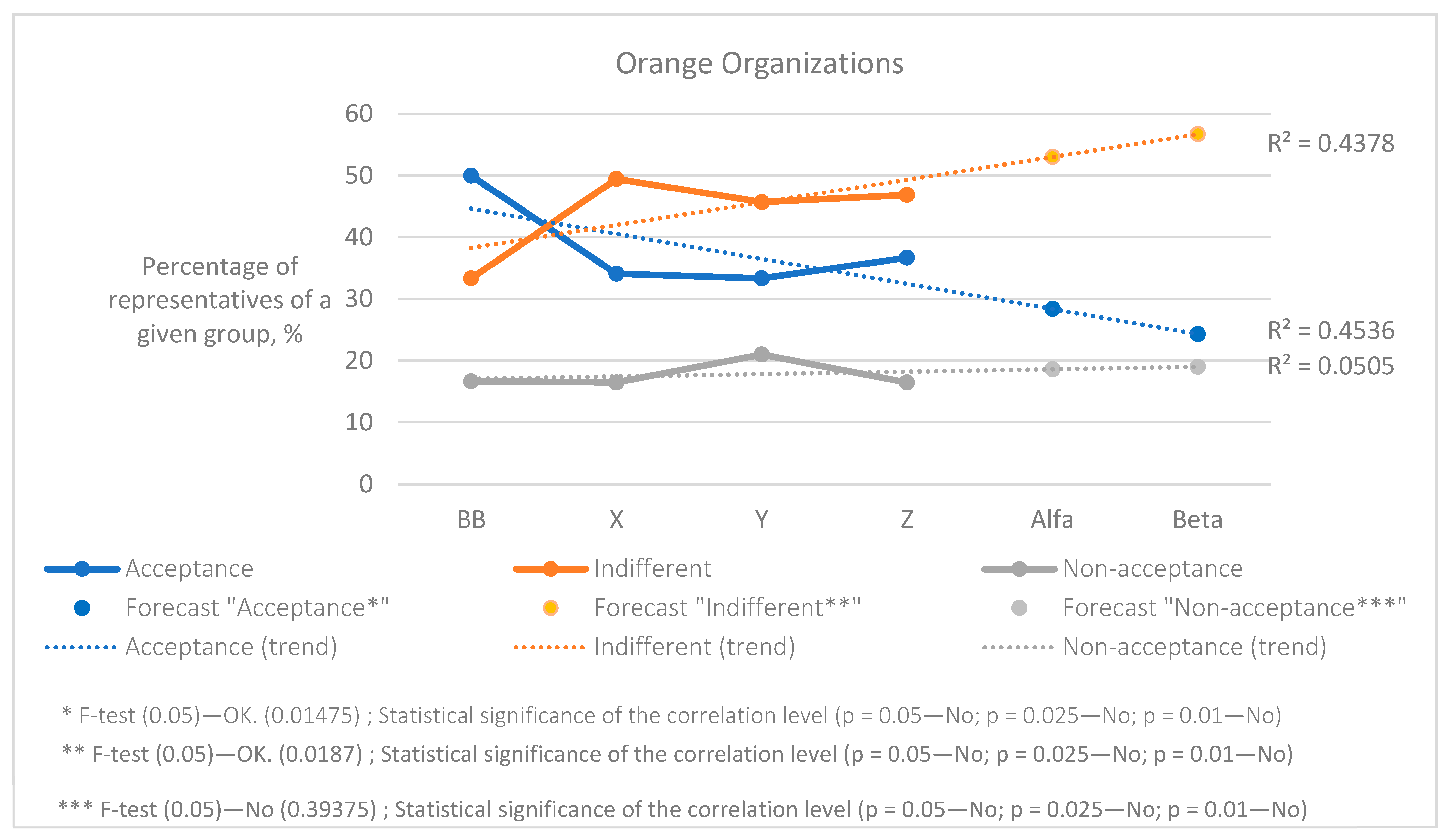

4.3. Acceptance of Organizational Management Models

4.4. Acceptance of Specific Features of the Tested Models

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammirato, S.; Felicettia, A.M.; Linzalone, R.; Corvello, V.; Kumar, S. Still our most important asset: A systematic review on human resource management in the midst of the fourth industrial revolution. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liboni, L.B.; Cezarino, L.O.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Oliveira, B.G.; Stefanelli, N.O. Smart industry and the pathways to HRM 4.0: Implications for SCM. Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 24, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J.; de Witte, M. Finally in Business: Organising Corporate Social Responsibility in Five. In Management Models for Corporate Social Responsibility; Jonker, J., de Witte, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloux, F. Reinventing Organizations, 10th ed.; Nelson Parker: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; pp. 13–36+337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Thoumrungroje, A.; Suprawan, L. Investigating M-Payment Intention across Consumer Cohorts. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bu, H.; Sun, H. The Impact of On-the-Job Consumption on the Sustainable Development of Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Qenaat, B.; Taj, S.; Khan, Z.U.; Khan, M.M.; Rabnawaz, M.; Yawar, R.B. Toward inclusive growth: Technology in development economics through the lens of bibliometric analysis. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S. Sustainability as a driver for corporate economic success: Consequences for the Development of Sustainability Management Control. Soc. Econ. 2011, 33, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Scavarda, L.F.; Vidal, G.; de Mattos Nascimento, D.L.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. A taxonomy of critical factors towards sustainable operations and supply chain management 4.0 in developing countries. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 34, 744–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.M.; Uruburu, Á.; Jain, A.K.; Ruiz, M.A.; Gómez Muñoz, C.F. The Path towards Evolutionary—Teal Organizations: A Relationship Trigger on Collaborative Platforms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, S. Industry 5.0—A Human-Centric Solution. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akundi, A.; Euresti, D.; Luna, S.; Ankobiah, W.; Lopes, A.; Edinbarough, I. State of Industry 5.0—Analysis and Identification of Current Research Trends. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.M.; Mende, M.; Grewal, D.; Parasuraman, A. The Fifth Industrial Revolution: How Harmonious Human–Machine Collaboration is Triggering a Retail and Service [R] evolution. J. Retail. 2022, 98, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation; Breque, M.; De Nul, L.; Petridis, A. Industry 5.0–Towards a Sustainable, Human-Centric and Resilient European Industry; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M. Przynależność do kohorty pokoleniowej jako determinanta korzystania z BLIK-a. Bank I Kredyt 2023, 54, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- De Smet, A.; Mugayar-Baldocchi, M.; Reich, A.; Schaninger, B. Gen What? Debunking Age-Based Myths About Worker Preferences. 2023. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/gen-what-debunking-age-based-myths-about-worker-preferences#/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Trzcionka, M. Turkusowa organizacja: żywy organizm. In Wybrane Aspekty Przemian Gospodarczych w Polsce; Geise, M., Oczki, J., Piotrowski, D., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2018; pp. 138–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Muñoz, C.F.; Moreno Romero, A. Progressing toward Teal Organizations: An Assessment of Organizational Innovation in the Spanish Public Administrations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowska, B. Teal Organizations: Literature Review and Future Research Directions. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 27, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, J. Does teal suit everyone? Psychosocial factors affecting work attractiveness in an organisation with a horizontal structure. Soc. Inequalities Econ. Growth 2020, 62, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, G.; Dechter, E.; Ivancic, L. Conformity and adaptation in groups. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2023, 212, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, M. Współczesne modele (kolory) zarządzania. Eur. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygadło, A. Sense of subjectivity and employee engagement in contemporary self-managing organizations. Relacje. Stud. Z Nauk Społecznych 2018, 5, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin-Skorecka, K.; Motała, D.; Boguszewska, K. Generation Z is not ready for work in teal organization. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Poznańskiej Ser. Organ. I Zarządzanie 2023, 87, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Edmondson, A.C. Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bańkowska, M. From Amber to Teal: Perspectives of library administration changes in the context of vocational colleges. Nowa Biblioteka. Usługi Technol. Inf. I Media 2020, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, J. Analysis of Selected Factors of the Motivation System of Employees for Professional Involvement in the Organizations of the Silesian Voivodeship. Humaniz. Pr. 2017, 4, 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Blikle, A.J. Doktryna Jakości. Rzecz o Turkusowej Samoorganizacji, 3rd ed.; OnePress: Gliwice, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ziębicki, B. Organizations without “Bosses”-Modern Fashion or a New Management Paradigm? Humaniz. Pr. 2017, 4, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Holwek, J. Let’s drop this turquoise trend. How beautiful practice becoming mode and even ideology. Coach. Rev. 2018, 10, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopej-Tomaszycka, M.; Hopej, M. Organizational structures in turquoise organizations. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śląskiej Ser. Organ. I Zarządzanie 2018, 130, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, R.; Rzepka, A.; Borowiecki, R.; Olesińki, Z. Energy Efficiency in the Industry 4.0 Era: Attributes of Teal Organisations. Energies 2021, 14, 6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummelstedt, C. The Role of Hierarchy in Realizing Collective Leadership in a Self-Managing Organization. Syst Pr. Action Res 2022, 36, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiecki, R.; Olesinski, Z.; Rzepka, A.; Hys, K. Development of Teal Organisations in Economy 4.0: An Empirical Research. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiluk, A. On the Way to Turquoise Organizations and Turquoise Leadership. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2022, 158, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL Khoury, M.; Jaouen, A.; Sammut, S. The liberated firm: An integrative approach involving sociocracy, holacracy, spaghetti organization, management 3.0 and teal organization. Scand. J. Manag. 2024, 40, 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarska, A.M.; Iwko, J. The Aspects of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Job Candidates’ Recruitment and Selection Processes in a Teal Organization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaszewska-Zajbert, E.; Sokołowska-Durkalec, A. Coaching as an Instrument for Support of Turquoise Organization Model. Przedsiębiorczość I Zarządzanie 2018, 8, 617–629. [Google Scholar]

- Kozina, A.; Pieczonka, A. “Turquoise Approach” to Managing Organizational Conflicts. Mark. I Zarządzanie 2018, 1, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagala, M.; Babčanová, D. Preferences of Generations of Customers in Slovakia in the Field of Marketing Communication and Their Impact on Consumer Behaviour. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.; Paraboni, A.; Matsushita, R. Adapting the National Financial Capability Test to Address Generational Differences in Cognitive Biases. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Kroenke, A. The generation of the future. Can and how can Generation Alpha change the labour market? Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Humanit. Zarządzanie 2024, 25, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrindle. Understanding Generation Alpha; McCrindle Research: Norwest, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F.; Hofmeister, A. Baby Boomers of different nations: Identifying horizontal international segments based on self-perceived age. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, M. Young people from the Z and Alpha generations as a task for educators, i.e., about the need to “catch a wave”. Kwart. Nauk. Fides Ratio 2020, 4, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Kłos, M. Pokolenie Y—Prawdy i mity w kontekście zarządzania pokoleniami, „Marketing i Rynek”, Nr. 5/2014, ss. 923–929. 2014. Available online: https://www.pwe.com.pl/czasopisma/marketing-i-rynek/numery-czasopisma/marketing-i-rynek-nr-052014,p1626926434 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Mahapatra, G.P.; Bhullar, N.; Gupta, P. Gen Z: An Emerging Phenomenon. NHRD Netw. J. 2022, 15, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidhani, S.; Lokesh Arora, L.; Sharma, B.K. Understanding the Attitude of Generation Z towards Workplace. Int. J. Manag. Technol. Eng. 2019, 9, 2804–2812. [Google Scholar]

- Changing Generations. Available online: https://mccrindle.com.au/app/uploads/images/GenZGenAlpha.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- McCrindle. The Generations Defined. Navigating the New Landscape of Employees and Consumers; McCrindle Research: Norwest, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Trancoso, T. From Risk to Reward: Understanding the Influence of Generation Z and Personality Factors on Sustainable Entrepreneurial Behaviour. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2024, 23197145241271467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleśna, A. Three Generations X, Y, and Z and their Expectations of a Prospective Employer Related to CSR. Przegląd Organ. 2018, 4, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generation Name | Birth Years 1 | Social Events 2 | Typical Technology 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baby Boomers | 1946–1964 | Moon landing (1969) | Transistor radio, TV, cassette tapes |

| Generation X | 1965–1980 | Stock market crash (1987) | VCR tapes, personal computers (PC), Walkman |

| Generation Y | 1981–1996 | Onset of terrorism (11 September 2001) | Internet, e-mail, SMS, DVD, PlayStation, Xbox, iPod |

| Generation Z | 1997–2009 | Global financial crisis (2008) | Google, Wikipedia, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, iPhone, Spotify |

| Generation Alpha | 2010–2025 | COVID-19 pandemic (2020) | iPad, Instagram, FaceTime, Siri, Apple Watch, TikTok, smart speakers |

| Characteristic | Share in the Research Sample [%] |

|---|---|

| Generational cohort | |

| Generation X | 34.60 |

| Generation Y | 30.80 |

| Generation Z | 30.04 |

| Baby Boomers (BB) | 4.56 |

| Gender (p 1 = 0.11262) | |

| Female | 69.20 |

| Male | 30.80 |

| Education (p 1 = 0.36954 2) | |

| Higher education | 62.74 |

| Secondary education | 26.62 |

| Doctorate | 5.32 |

| Vocational education | 4.18 |

| Primary education | 0.76 |

| No formal education | 0.38 |

| Employment status (p 1 < 0.00001 3) | |

| Employed | 75.67 |

| Unemployed | 10.27 |

| Employer | 7.22 |

| Occasional work | 6.84 |

| Red Organizations | Amber Organizations | Orange Organizations | Green Organizations | Teal Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian management | Stability of operating principles | Management by objectives | Participation | Self-management |

| Punishment for mistakes | Promotion based on seniority | Meritocracy | Feedback | Collaboration and servant leadership |

| Organizational effectiveness based on the manager | Lack of creativity | Individual competition | Interpersonal relationships | Open access to information and flexibility |

| Lack of coherence in operations | Resistance to change | Creativity aimed at performance improvement | Flat organizational structure | Mistakes as opportunities for learning and growth |

| Lack of long-term planning | Extensive organizational structure | Prioritizing goals over personal needs | Sustainable development | Trust and mutual respect |

| Parameter | Red Organizations | Amber Organizations | Orange Organizations | Green Organizations | Teal Organizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work experience [share of respondents] | 19.77% | 19.39% | 28.52% | 25.10% | 24.71% |

| Partial work experience [share of respondents] | 27.38% | 30.80% | 40.30% | 34.60% | 30.42% |

| Mean experience rating 1 | 3.30 | 3.24 | 2.69 | 1.88 | 2.01 |

| p-value: chi-square test (α = 0.05) for the assessment of experiences by generational affiliation | 0.47543 | 0.24878 | 0.97781 | 0.07725 2 | 0.26095 2 |

| Model Acceptance | Chi-Square Test (α = 0.05) | |

|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Is the Acceptance Dependent on Generation (p < α)? | |

| Red organizations | 0.06647 | - |

| Amber organizations | 0.79409 | - |

| Orange organizations | 0.90387 | - |

| Green organizations | 0.08427 * | - |

| Teal organizations | 0.00962 | Yes |

| Characteristic | Mean Rating | Chi-Square Test (α = 0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Is the Acceptance Dependent on Generation (p < α)? | ||

| Red organizations | |||

| Authoritarian management | 3.46 | 0.37520 | - |

| Punishment for mistakes | 3.61 | 0.00007 | Yes |

| Lack of coherence in operations | 4.09 | 0.40851 1 | - |

| Organizational effectiveness based on the manager | 2.89 | 0.11063 | - |

| Lack of long-term planning | 3.83 | 0.66554 | - |

| Amber organizations | |||

| Stability of operating principles | 2.99 | 0.03786 | Yes |

| Promotion based on seniority | 3.71 | 0.32935 | - |

| Lack of creativity | 3.63 | 0.38380 | - |

| Resistance to change | 3.67 | 0.44251 | - |

| Extensive organizational structure | 3.41 | 0.00204 | Yes |

| Orange organizations | |||

| Management by objectives | 2.85 | 0.03017 | Yes |

| Meritocracy | 1.76 | 003168 2 | Yes |

| Individual competition | 3.42 | 0.08648 | - |

| Creativity aimed at performance improvement | 2.84 | 0.01059 | Yes |

| Prioritizing goals over personal needs | 2.98 | 0.21204 | - |

| Green organizations | |||

| Participation | 1.63 | 0.60162 2 | - |

| Feedback | 1.61 | 0.00459 2 | Yes |

| Interpersonal relationships | 1.56 | 0.10471 2 | - |

| Flat organizational structure | 1.65 | 0.76811 2 | - |

| Sustainable development | 2.02 | 0.16831 | - |

| Teal organizations | |||

| Self-management | 2.89 | 0.00001 | Yes |

| Collaboration and servant leadership | 2.11 | 0.04681 | Yes |

| Open access to information and flexibility | 1.95 | 0.29890 2 | - |

| Mistakes as opportunities for learning and growth | 1.91 | 0.00008 | Yes |

| Trust and mutual respect | 1.57 | 0.03926 2 | Yes |

| Characteristic | Baby Boomers | Generation X | Generation Y | Generation Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punishment for mistakes | 3.42 | 3.31 | 3.40 | 4.20 |

| Stability of operating principles | 2.92 | 3.35 | 2.91 | 2.66 |

| Extensive organizational structure | 3.50 | 3.30 | 3.30 | 3.66 |

| Management by objectives | 2.58 | 2.93 | 2.91 | 2.73 |

| Meritocracy | 1.75 | 1.95 | 1.89 | 1.43 |

| Creativity aimed at performance improvement | 2.33 | 2.80 | 2.86 | 2.92 |

| Feedback | 2.00 | 1.81 | 1.60 | 1.32 |

| Self-management | 3.50 | 3.35 | 2.78 | 2.37 |

| Collaboration and servant leadership | 2.58 | 2.33 | 2.10 | 1.80 |

| Mistakes as opportunities for learning and growth | 2.42 | 2.22 | 1.91 | 1.47 |

| Trust and mutual respect | 1.75 | 1.70 | 1.63 | 1.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sytnik, I.; Franke, E.; Stopochkin, A. Intergenerational Differences in the Perception of the Assumptions of Individual Organizational Management Models in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156776

Sytnik I, Franke E, Stopochkin A. Intergenerational Differences in the Perception of the Assumptions of Individual Organizational Management Models in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156776

Chicago/Turabian StyleSytnik, Inessa, Eryk Franke, and Artem Stopochkin. 2025. "Intergenerational Differences in the Perception of the Assumptions of Individual Organizational Management Models in the Context of Sustainable Development" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156776

APA StyleSytnik, I., Franke, E., & Stopochkin, A. (2025). Intergenerational Differences in the Perception of the Assumptions of Individual Organizational Management Models in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 17(15), 6776. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156776