Abstract

In the current era of a dynamic environment, organizations need to continuously innovate and transform to remain competitive. Digital transformation is an essential driver across organizations, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), reshaping organizational agility. This research examines the interconnection among knowledge sharing, digital transformation, open innovation, organizational agility, and transformational leadership. A quantitative research design was employed, using an online survey with data collected from 543 participants selected through a stratified random sampling from SMEs in China. Data were analyzed by utilizing partial least squares structural equation modeling. The results include a significant impact of knowledge sharing on digital transformation, digital transformation on open innovation, and open innovation on organizational agility. Additionally, digital transformation and open innovation were found to significantly mediate the relationship between knowledge sharing and open innovation and organizational agility. Moreover, transformational leadership significantly moderated the impact of digital transformation on open innovation. The model explained 67.7% of the variation in organizational agility. The research provides a holistic model for SMEs aiming to leverage information sharing, technological integration, and leadership practice to improve flexible and innovative systems, contributing to theoretical understanding and practical solutions to sustainable resilience.

1. Introduction

In the current era of accelerated technological change and dynamic business environments, organizations need to continually evolve and innovate to ensure competitiveness and sustainability [1]. The increasing speed of technological disruption is revolutionizing conventional business models, demanding intelligence-driven, collaboration-oriented, and adaptive organizational designs [2]. Managing this digital change is both essential and challenging, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which often face resource constraints [3,4].

Although there is a growing interest in studying digital transformation, several research gaps remain [5]. First, there is scant knowledge on the role of open innovation and knowledge sharing in enabling organizational agility, especially under the influence of transformational leadership [6]. Second, few studies examine these relationships in SMEs, more so in emerging economies where organizations face technological disruption and resource scarcity [4,6]. This study aims to fill these gaps by proposing and examining a comprehensive model that incorporates knowledge sharing, open innovation, organizational agility, and transformational leadership within the context of SMEs.

Digital transformation refers to the complete integration of digital technologies into all aspects of an organization, radically changing its operational processes, value delivery, and customer engagement [7,8]. However, successful digital transformation requires not only the adoption of technology but also a cultural transformation, where collaboration, innovation, and responsiveness are valued [9]. It is considered one of the major factors of competitiveness and sustainability in today’s knowledge economy [10].

In today’s knowledge-driven economy, firms are becoming increasingly dependent on knowledge, and therefore, knowledge sharing has become a critical high-performance practice essential for their survival [11]. Knowledge sharing is a key high-performance indicator, encompassing the dissemination of knowledge, competencies, and expertise across organizational units [12]. Additionally, it enhances collaboration, accelerates decision-making, and fosters innovation, enabling firms to respond to dynamic market changes [13,14]. Moreover, facilitating effective knowledge sharing enables firms to build strategic flexibility and adaptive capabilities, which are essential for navigating technological disruptions. Furthermore, open innovation enables the combination of internal and external knowledge, enhancing an organization’s capacity through the involvement of stakeholders like customers, partners, and competitors [15]. This collaborative approach strengthens a firm’s ability to develop novel solutions, shorten innovation cycles, and remain responsive to evolving technological and market dynamics [16]. In digital transformation, open innovation is critical in fostering adaptability and unlocking new pathways for traditional R&D through collaborative initiatives [17].

Organizational agility refers to a firm’s ability to rapidly sense, interpret, and respond to changes in its external environment [18,19]. Structural flexibility, a learning-oriented culture, and an adaptive strategic posture characterize it [20]. Agility enables firms to navigate uncertainty, seize emerging opportunities, respond to digital disruption with speed and precision, and maintain sustainable competitive advantage [21,22]. In the banking sector, for instance, agility enables the bank to introduce new products quickly, simplify operations, and become more responsive to customers [23].

Transformational leadership plays a moderating role, strengthening the link between open innovation and organizational agility. Transformational leaders establish trust, motivation, and a shared vision, leading employees to embrace change and exceed expectations [24]. Such leadership ensures the alignment of individual and organizational goals, fostering innovation and agility in addressing dynamic and volatile business environments [25,26,27].

Rooted in the above considerations, our research proposes an integrated model to explore the connections between knowledge sharing and open innovation in developing organizational agility, with transformational leadership serving as a moderator during digital transformation [28]. The study addresses the following research goals:

- (1)

- To explore the relationship between knowledge sharing, digital transformation, open innovation, and organizational agility.

- (2)

- To investigate the individual and serial mediating roles of digital transformation and open innovation in the relationship between knowledge sharing and organizational agility.

- (3)

- To test the moderating role of transformational leadership in the relationship between digital transformation and open innovation.

This study examines Chinese SMEs, which are vital to economic growth, contributing to over 79% of employment, 60% of GDP, 68% of trade, and 50% of taxation [29,30]. As they are significant, SMEs need strategies for managing technology disruption. This research contributes both theoretically and practically. Theoretically, it integrates the resource-based view [31], dynamic capabilities theory [32], and transformational leadership theory [33] to explain how leadership behavior and knowledge-based practices facilitate organizational agility through digital and open innovation processes. Additionally, it contributes to the context of emerging economies and SMEs, which require empirical evidence in the current era of digital transformation [34,35]. Lastly, it provides practical guidance to managers on how to strategically coordinate knowledge practices and leadership to foster innovation and agility in digitally transforming environments.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Support

This research is underpinned by an integrative theoretical framework founded on the resource-based view [31], dynamic capabilities theory [32], and transformational leadership theory [33]. Its goal is to clarify the interconnections among digital transformation, knowledge sharing, open innovation, organizational agility, and transformational leadership in the context of SMEs embracing digital transformation.

The resource-based view theory gives the underlying rationale for explaining how a firm’s internal resources, such as technological infrastructure and knowledge, can be utilized to gain a competitive advantage. It is those resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable that account for long-term organizational success, according to RBV [31]. Knowledge sharing is shown here as a strategic intangible asset enabling digital transformation by exchanging insights, knowledge, and best practices across organizational units [36]. In addition, digital transformation is also a capability development process depending on the firm’s capacity to combine and mobilize such knowledge assets to deliver enhanced efficiency, responsiveness, and innovation [6]. Therefore, RBV validates the correlation between knowledge sharing and digital transformation (H1) and digital transformation’s role as a mediator in the translation of knowledge into innovation (H5).

Though RBV succeeds in capturing the significance of firm-specific resources, it falls short in capturing the dynamism of fitting into rapidly changing environments. This shortfall is compensated for by the dynamic capabilities theory [32], which focuses on the capacity of a firm to sense opportunities and threats, seize opportunities, and reshape its resource base to ensure competitiveness in uncertain environments [37]. The DCT is employed in this study to explain organizational agility and the utilization of open innovation [38]. Open innovation allows companies to recombine internal and external sources of knowledge and thereby enhance their dynamic capabilities to innovate and respond rapidly to technological discontinuities and market changes [39]. Organizational agility, which is the ability to sense and react to change rapidly, is a higher-order dynamic capability that depends on innovation and knowledge processes. Therefore, the DCT validates the postulated sequences of digital transformation to open innovation (H2), open innovation to organizational agility (H3), and the serial mediating route from knowledge sharing to agility through digital transformation and open innovation (H6).

Complementing these resource- and capability-based approaches is transformational leadership theory, which accounts for the role of leadership behavior in organizational change and innovation [40]. Transformational leaders motivate, intellectually stimulate, and empower followers to accept change and strive for shared goals [33]. Transformational leadership in digitizing companies promotes experimentation, openness, and the culture of trust, precursors to successful innovation [41,42]. This leadership approach improves the performance of digital initiatives by linking employees’ behavior to the strategic goals of innovation and agility [43]. Transformational leadership is suggested in this research to play a mediating role in the association between digital transformation and open innovation, improving the degree to which digital innovations are implemented in terms of collaborative innovation (H7). Transformational leaders have the capacity to minimize resistance towards change, facilitate cross-functional working, and prompt active employee participation in digital innovation projects.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Knowledge Sharing and Digital Transformation

Knowledge sharing is crucial to organizations’ digital transformation [44]. It facilitates the dissemination of information and knowledge, which is necessary for effective technology integration [45]. Knowledge-based theory posits that organizational knowledge is one of the resources for innovation and transformation [46]. We believe that digital transformation means using new technologies and incorporating collective knowledge to advance technological integration into processes [47]. Knowledge sharing has been shown to improve an organization’s readiness for digital technology [48]. Moreover, sharing knowledge creates a constructive attitude toward transformation, as experimentation and adoption of new technology can occur [36,49].

Effective knowledge sharing, such as technical guidance, enables alignment of digital strategies with operational goals, allowing firms to bridge silos and promote cross-functional working [12]. In addition, knowledge sharing encourages the development of a state of mind in a direction towards being digital, a requirement for an organization to transition towards a more digitally intensive environment [7]. Research conducted by Guo et al. [50] found that effective knowledge sharing in an organization promotes a less turbulent transformation in a direction towards being digital, with workers inclined towards offering helpful information regarding technological innovation. Furthermore, it is reported that an organization with a high level of information dissemination can effectively overcome complexity in a digital transformation [4]. Hence, we suggest the following:

H1:

Knowledge sharing significantly and positively affects digital transformation.

2.2.2. Digital Transformation and Open Innovation

Digital Transformation is a key enabler of open innovation because it allows businesses to leverage internal and external knowledge resources to improve their innovation activities [3,4,5]. By utilizing digital technologies like artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and the IoT, companies obtain new competencies, foster experimentation, and speed up the creation of novel products, services, and business models [51]. By combining digital platforms, companies encourage collaboration across various boundaries, hence speeding up the processes of idea generation, experimentation, and scaling innovations [52,53].

In a context where technology evolves at a high speed, digital transformation enables firms to open up their innovation ecosystems so that they can co-create value along with partners, customers, and stakeholders [54,55]. This implies that digital transformation not only enables internal process effectiveness but also opens up fresh avenues for decentralized as well as collective innovation approaches [56]. Moreover, Xu et al. [57], using a sample of A-Share-listed companies in China, observed a significant influence of digital transformation on firm open innovation. Jing and Qu [58] also showed a significant connection with digital transformation in the A-Share-listed firms in China. A recent study by Yun et al. [59] reported this relationship in the context of Germany, Japan, and South Korea. Hence, we suggest the following:

H2:

Digital transformation is significantly and positively affecting open innovation.

2.2.3. Open Innovation and Organizational Agility

Open innovation is essential to organizational agility in today’s rapidly changing business world [60]. By leveraging external and internal knowledge, organizations can respond quickly to technological changes, changing customer requirements, and competition [61]. Open innovation enables quicker ideas, quicker solutions, and increased flexibility that are essential to build agility [62]. Furthermore, it allows companies to operate beyond internal boundaries with external partners like customers, suppliers, and competitors [63]. It also enhances learning capacity, which provides more opportunity for sensing and responding to disruption, and resource reconfiguration, the essence of agility [60].

Dynamic capability theory [32] highlights the fact that the ability of an organization to integrate and reconfigure competencies is essential for competitive advantage in dynamic environments. Considering this perspective, open innovation enhances such capabilities, as it fosters continuous exploration and exploitation of new knowledge and resources [64,65]. Furthermore, studies also showed a significant link between open innovation and organizational agility in different contexts. For instance, Urresta-Vargas et al. [66] reported this among Colombian manufacturing companies, and Salmerón et al. [67] observed it in industrial exporting companies. Hence, we suggest the following:

H3:

Open innovation significantly and positively affects organizational agility.

2.2.4. Digital Transformation as Mediator

The resource-based view theory posits that firms use internal resources like technology and knowledge to attain competitive advantage [31]. Considering this perspective, digital transformation is at the heart of knowledge sharing, as it offers the infrastructure, platforms, and tools necessary for knowledge sharing across organizations [68,69]. It supports the transfer of insights and best practices by adopting new technologies for quicker and more effective knowledge integration. Hence, digital transformation is increasingly a key mediator linking different constructs [70].

Furthermore, dynamic capabilities theory emphasizes that companies need to adjust their capabilities to evolving environments [32]. In this respect, digital transformation enhances a firm’s capacity to sense and respond to new opportunities, playing a key mediating role in the translation of shared knowledge into innovation. Digital organizational processes and technology adoption facilitate innovation and rapid growth for an organization [71]. Knowledge sharing, facilitated by digital tools, becomes a dynamic force driving reconfiguration and innovation [72]. Furthermore, digital transformation bridges open innovation and knowledge sharing, as it allows organizations to integrate knowledge from outside and to collaborate better with partners, customers, and competitors [72,73]. Research shows that organizations that have advanced digital tools transition to novel solutions better by closing knowledge gaps and facilitating collaboration [74]. Hence, we suggest the following:

H4:

Knowledge sharing indirectly influences open innovation through digital transformation.

2.2.5. Open Innovation as Mediator

Digital transformation generates agility in an organization by generating new processes and new solutions [75,76]. Rapid adaptability in a changing environment in a marketplace is a function of capacities developed through digital technology. As per studies, through new products, new service offerings, and new forms of business, an organization, through digital transformation, can become adaptable [77,78]. Innovation through digital technology enables an organization with tools and processes to become flexible and sensitive to changing environments in an external environment. Innovation in an organization is a mediator between transformation and agility [79].

With digital transformation, an organization can introduce new technology, develop its innovation capacity, and then improve its agility and rapid decision-making [51,60,74]. Innovation enables an organization to re-strategize and realign its strategies with changing marketplace environments, enabling its agility in a competitive environment [80]. With digital platforms, organizations can innovate and adapt rapidly in a changing business environment [80]. Hence, we suggest the following:

H5:

Digital transformation indirectly influences organizational agility through open innovation.

2.2.6. Serial Mediation of Digital Transformation and Open Innovation

Knowledge sharing is an enabler of open innovation and digital transformation, and in return, both contribute to organizational agility [6]. Sharing knowledge empowers workers in an organization to collaborate and pool each other’s expertise and utilize digital technology that empowers them for digital transformation [28]. The sharing of knowledge aids in the effective absorption of new tools and processes, and such tools and processes become a part of digital transformation [81]. In return, such an impact is extended toward open innovation by imparting information to workers to develop new goods, services, and methodologies.

Sequential mediation of open innovation and digital transformation most applies to organizational agility. Digital transformation empowers organizations with tools and capabilities for rapid innovation, and innovation, in return, empowers them to become flexible and adaptable in changing environments [82]. Together, a connection between knowledge sharing, digital transformation, and innovation forms a loop for continuous improvement and adaptability, and through such, organizations become even more agile. For example, organizations with a shared environment for information empower them with digital competencies; through such, organizations become capable of developing responsiveness towards change in the environment [83]. Therefore, such a sequence of knowledge sharing towards agility through digital transformation and innovation is well established. Through such, each of them empowers an organization to develop a flexible and adaptable organization [84].

H6:

Knowledge sharing indirectly influences organizational agility through the sequential mediation of digital transformation and open innovation.

2.2.7. Transformational Leadership as Moderator

For a long time, transformational leadership has been considered to have a significant impact in terms of energizing and inspiring workers toward transformation and driving innovation [85]. It is considered most relevant in driving digital transformation, as it inspires workers towards innovation and transformation towards new technology [43,86]. Transformational leadership theory [87] emphasizes that visionary leaders who promote innovation and individualized consideration exert direct influence on organizational change initiatives.

Transformational leaders in digital transformation and open innovation have a paramount moderating effect by shaping a culture fostering experimentation, risk-taking, and cross-border collaboration [40]. By fostering a culture that is open, reliable, and innovative, transformational leaders enhance the impact of digital transformation on open innovation, thereby enhancing the capacity of the organization to innovate and succeed in ever-changing markets [42,75]. A study by Ting et al. [88] observed a significant but negative moderation impact of transformational leadership on knowledge management and firm innovative performance in Malaysian companies. Following the above arguments and empirical evidence, we suggest the following:

H7:

Transformational leadership and digital transformation interaction significantly influence open innovation.

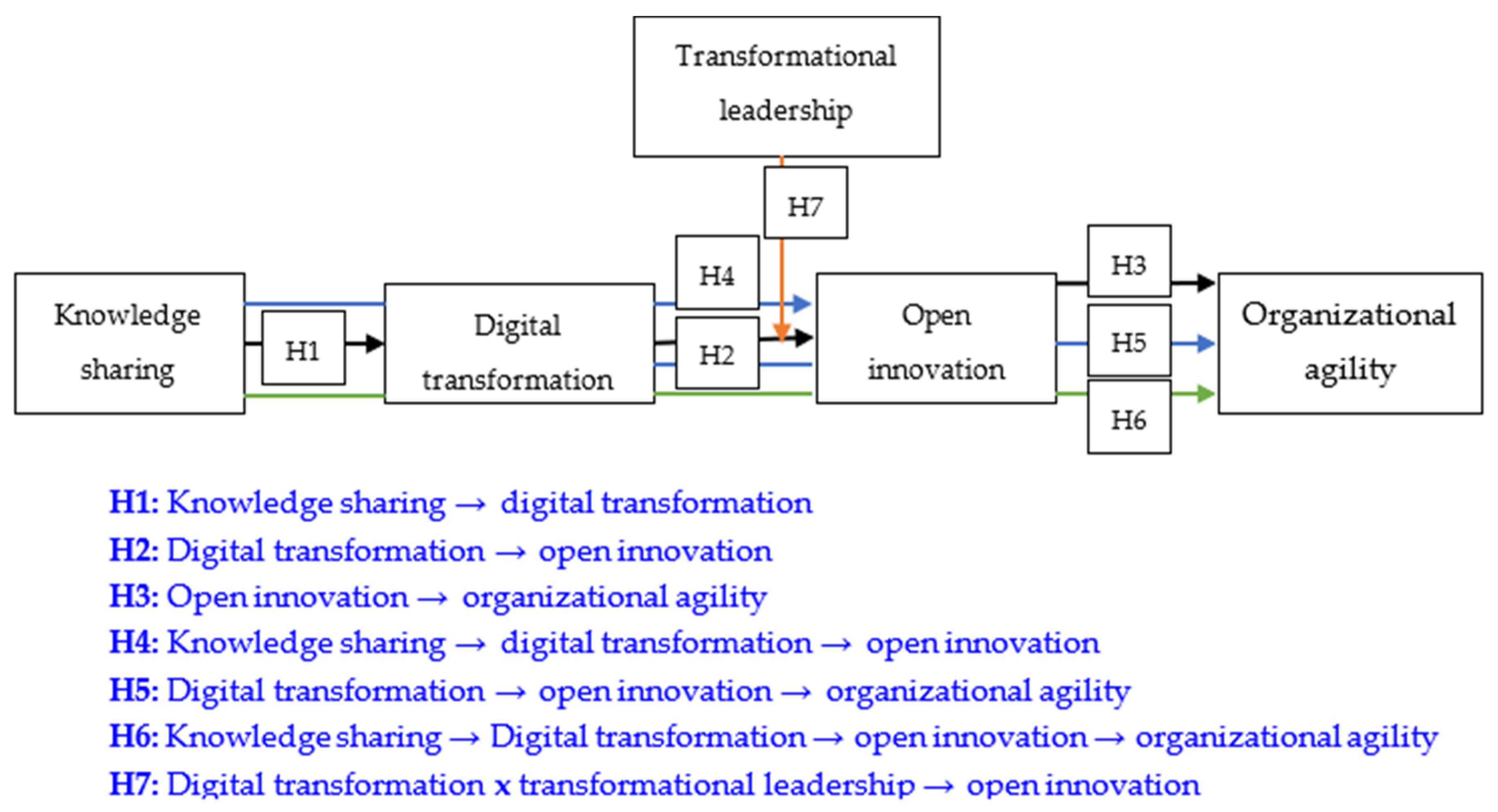

Figure 1, given below, illustrates the study assumption. In particular, black, blue, and green arrows show direct, mediation, and moderation relationships, respectively.

Figure 1.

The proposed model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

We adopt a quantitative study design to examine relations between transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, digital transformation, open innovation, and organizational agility in SME settings. We chose this research design because it offers precise, measurable, and statistically analyzed data that enables the testing of complex relationships between constructs [89]. Additionally, the design facilitates replicability, thereby increasing the reliability and validity of the findings [90].

To minimize biases, we took several precautions. First, a time-lagged multi-wave survey collected independent and dependent variables at different points in time to reduce common method bias [91,92]. Second, when designing the questionnaire, we ensured anonymity, promised confidentiality, and assured participants that there were no right or wrong answers, thereby minimizing evaluation apprehension and social desirability bias [30].

The study sampled SME managers and employees in Jiangsu Province, China, who were involved in knowledge sharing, digitalization activities, and leadership. Stratified random sampling ensured sample representativeness and diversity [93]. Strata were characterized by three dimensions: department (operations, IT, HR, marketing, R&D), management level (senior managers, middle managers, employees), and firm size (small or medium SMEs). The stratification captured diverse perceptions, enabling the results to be more generalizable and valid [29].

3.2. Data Collection

Five hundred and forty-three valid responses were collected through an online survey from January to March 2023. Electronic media, especially WeChat and QQ, were used to distribute questionnaires and ease respondents’ use. Two follow-up reminders were sent for high response rates. Out of 543 participants, a majority were male (326), and 217 were female. Additionally, 33, 280, 180, and 50 held diplomas/other, bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees, respectively. Moreover, 85, 220, 150, and 88 had a monthly salary < 6000, 6000–10,000, 10,000–15,000, and over 15,000, respectively.

Key enterprise characteristics were also captured in the study for those firms in the sample, predominantly based on SMEs. The responding companies spanned different industries, including manufacturing (e.g., Zhenjiang Longshun Company, Zhenjiang Chemical Industry Company; Everbright Materials Technology Changzhou Co., Ltd.; clean energy: Changzhou Trina Solar; textiles: Changzhou Starlight Textiles; healthcare: People’s First Hospital, Zhenjiang, Jiangben Hospital; and logistics: Zhenjiang Port Group). Approximately 65% of these enterprises were classified as small (fewer than 100 employees), with the remaining 35% as medium-sized (100–300 employees). Firm age distribution indicated that 31% were younger than five years, 43% had operated between 5 and 15 years, and 26% were over 15 years old. Geographically, most firms were in Zhenjiang, Changzhou, Nanjing, Suzhou, and Yangzhou—economic hubs within Jiangsu. Regarding digital maturity, 36% of firms reported being in early digital stages, 44% at intermediate levels, and 20% as digitally mature. Many enterprises maintained active collaborations with local universities, suggesting a strong regional ecosystem for innovation, digital transformation, and knowledge exchange.

3.3. Measurements

A 5-point Likert scale was used to rate the items. Knowledge sharing was measured using a 4-item scale adapted from Fischer [94] and Oliveira [95]. A sample item is “Our organization encourages knowledge sharing.” Digital transformation was measured using a 4-item scale adapted from AlNuaimi et al. [75]. A sample item is “Our organization strives to digitalize everything possible.” A 5-item scale adapted from Hung and Chou [96] was used to measure the open innovation. A sample item is “Our organization welcomes ideas from internal and external sources, like customers, and employees, to drive innovative ideas and innovation.” For assessing a moderator (transformational leadership), an 8-item scale was adapted from Altunoğlu et al. [41] and Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Metcalfe [97]. A sample of that is “Our organization’s leader, like immediate bosses, clearly communicates vision and goals.” A dependent variable (organizational agility) was measured using a 5-item scale adapted from Ly [26]. A sample item is “Our organization quickly adapts processes and activities to respond to dynamic changes”.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

In this study, the consent of all respondents was obtained in an informed manner for the conduct of the survey. Respondents understood the objective of the study well, volunteered to participate in a survey, and had the freedom to withdraw at any time at no penalty. Respondents were assured of anonymity, that responses would not be compromised, and that information collected would not disclose respondents’ anonymity, to protect respondents’ confidentiality. The use of respondents’ information for the purpose of research alone assured compliance with proper ethics in practice in research.

Respondents’ contribution to the survey was purely voluntary, and respondents were free to withdraw from the study at will. Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained in advance, and such approval guaranteed compliance with high ethical standards in the conduct of the study. Confidentiality of all responses was guaranteed; no information capable of identifying them was collected and revealed.

3.5. Data Analysis

The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized using SmartPLS 4.2 since it is suitable for complex models with several latent variables and effects. First, it handles such complexity well, even with small sample sizes, thus ensuring statistical power [90,98]. Second, PLS-SEM does not make strict distributional assumptions, and is thus appropriate for real organizational data that might not be normally distributed [99]. Third, PLS-SEM is extensively applied in theory development and exploratory studies where the objective is to predict important target constructs and examine intricate path relationships [100].

Structural model assessment tests hypothesized constructs’ relations through path coefficients. Model explanatory power is measured in terms of values of R2, and predictive explanatory power is measured in terms of Q2 statistics [101,102]. Tests for mediation analysis verify whether digital transformation and open innovation mediate between knowledge sharing and organizational agility. Tests for moderation analysis evaluate transformational leadership in modulating the relationship between digital transformation and open innovation [102].

4. Analysis of Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of Measurement Model

Metrics such as factor loading, Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and variance inflation factor (VIF) are suggested in testing a measurement model. Factor loading portrays the intensity of the relation between a construct and its items, with high values portraying high ties. Our item loading value is retained between 0.717 and 0.912 (see Table 1), while a suggested cutoff to accept the item loading is 0.70 [99]. CR tests are used for constructs’ internal consistency, and AVE tests for its convergent validity; their suggested cutoffs were 0.70 and 0.50, which are retained [99]. VIF tests are used for items’ multicollinearity, with high VIF values portraying concern for collinearity. Our work VIF is retained below 3.33, a suggested cutoff [99].

Table 1.

Assessment of reliability and convergent validity.

Discriminate validity is a significant constituent of SEM’s measurement model and confirms that discrete constructs actually vary with one another. Two tests for checking discriminant validity are the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) and Fornell–Larcker criteria, which are widely used these days when employing PLS-SEM for an analysis [91]. In the Fornell–Larcker criterion, when the square root of the AVE of a construct is larger in value compared to its relation with other constructs, then its discriminant validity is assured. The HTMT ratio is a relatively new tool, and a value less than 0.85 and 0.90 indicates discriminant validity [103,104] (see Table 2). In Table 2, values in diagonals represent the square root of AVE, and off-diagonal values represent constructs’ relation with one another. For instance, for DT, its square root of AVE is 0.814, larger in value with regard to its values with other constructs, such as KS at 0.797, OA at 0.869, OI at 0.853, and TL at 0.822.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity analysis using Fornell–Larcker and Heterotrait–Monotrait criteria.

4.2. Evaluation of Structural Model

Structural model analysis is an effective tool for testing hypothesized relations between constructs in a research model. By testing overall, direct, indirect, and moderation effects, researchers can confirm whether proposed relations in hypotheses have supporting information in the data. In such a case, information gained through analysis of a structural model describes the intensity and significance of such relations and about the mechanisms and interactions in a model by providing direction, intensity, and statistical significance, beta coefficients, t-value, and p-value reports about each relation, and values for R2 report about explanatory value in a model [105] (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the structural model.

The study observed a significant impact of knowledge sharing on digital transformation (β = 0.671, t = 33.296); hence, H1 is supported. It validates that companies’ drive towards digital transformation is a key driving force for knowledge sharing. It validates studies citing effective knowledge exchange as an essential driver for technological acceptance and creation [106,107].

The findings showed a significant impact of digital transformation on open innovation (β = 0.102, t = 3.812), validating H2. According to the output, digital transformation positively impacts open innovation, supporting that companies can use digital tools and platforms to conduct increasingly participative and dynamic processes of innovation [108]. The study also found a significant impact of open innovation on organizational agility (β = 0.811, t = 45.486), hence confirming H3. Open innovation helps a company become an agile one through its ability to react in a timely manner to external stimuli and demand in the marketplace [109].

Additionally, all three indirect effect hypotheses (H4, H5, H6) have significant beta values, t-values, and p-values supporting them [110]. H7 supported that transformational leadership significantly and negatively moderated the impact of digital transformation on open innovation (β = −0.138, t = 5.691). The significant moderation impact reveals leadership in driving technological change and innovation in an organization.

Table 3 illustrates that knowledge sharing, digital transformation, open innovation, and the moderation of transformational leadership combined explained 67.7% of organizational agility changes, which is considered acceptable, as it is above the cutoff of 0.10 [99]. Additionally, the effect size (f2) used to measure the strength of the connection between variables showed a large effect of knowledge sharing on digital transformation (f2 = 0.821) [91]. Our research showed a predictive relevance value such as Q2DT = 0.301 > 0 cutoff, which further assures that the model has substantial relevance.

4.3. Evaluation of Mediation Effect

In SEM, mediator effects refer to a way in which a variable (mediator) describes the relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable [111].

Our research employed a confidence interval approach to prove the mediation of digital transformation and open innovation. In particular, results supported H4, reflecting the indirect impact of knowledge sharing on open innovation via digital transformation (β = 0.068, t = 3.813, C.I = 0.035–0.106). The indirect effect 95% confidence interval is 0.035 to 0.106, and it is statistically significant since it does not contain zero [112]. This suggests that digital transformation strongly promotes knowledge sharing and innovation. The result confirms that the sharing of internal knowledge enables the adoption and implementation of digital technologies to improve the firm’s open innovation capability.

Furthermore, the study also showed a significant indirect impact of digital transformation on organizational agility via open innovation (β = 0.083, t = 3.798, C.I = 0.042–0.129), hence supporting H5. The effect’s confidence interval is 0.042 to 0.129, an indication of statistical significance. It implies that open innovation enables organizations to respond adaptively and agilely to technological advancements. Digital transformation by itself does not assure agility; its impact grows by innovative practices, triggering collaboration and rapid ideation. This supports the assertion that open innovation is essential to capitalize on digital assets to generate agility [62,66].

Moreover, findings prove a serial mediation of digital transformation and open innovation between knowledge sharing (β = 0.055, t = 3.816, C.I. = 0.029–0.086), hence supporting H6. The 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect is between 0.029 and 0.086, which does not cover zero, and this demonstrates its statistical significance. This route shows that knowledge sharing intensifies digital transformation, which leads to open innovation and organizational agility. The findings are consistent with innovation capability models, in which innovation and strategic tech integration translate internal knowledge into adaptive results [84].

4.4. Discussion

This study highlights how knowledge sharing, digitalization, open innovation, and transformational leadership enable organizational agility in SMEs. The findings contribute to the existing literature on knowledge management, digitalization, open innovation, leadership, and dynamic capabilities.

Specifically, knowledge sharing emerges as a foundational driver, influencing digital transformation [44] and, consequently, fostering open innovation [3,4,5] and organizational agility [68,69]. These findings align with the resource-based view, which focuses on intangible resources for competitive reasons [31]. It enables the spread of skills and expertise among units, facilitating digital adoption and the integration of technologies [3,34]. Earlier research suggests that strong knowledge-sharing cultures help organizations seize digital opportunities and overcome technological inertia [12,72].

The study finds that digital transformation enhances open innovation, supporting open innovation theory [113]. Emerging digital technologies help firms to cross boundaries, facilitate collaboration, and involve external actors like customers and suppliers. This enhances innovation capabilities, increases absorptive capacity [114], and speeds up product development. This finding highlights that virtual environments increase productivity and support co-creation of knowledge and joint innovation [115].

The findings demonstrate a strong correlation between open innovation and organizational agility, with the implication that firms that trade external knowledge adapt better to changing markets. This validates dynamic capabilities theory [37], in which agility reflects the ability of a firm to sense, seize, and reconfigure resources during periods of environmental change. Firms enhance their ability to adapt to technological upheavals, consumer shifts, and competition by adopting external knowledge [116]. This indicates that agility is a strategically designed competence, supported by digital and open innovation [67,117].

The integration of advanced technologies enables the development of novel processes, products, and services, strengthening an organization’s ability to maintain a competitive advantage [118]. The study validates the assertion that digital transformation acts as a catalyst for innovation, not only enhancing operational efficiency but also fostering a more participatory and dynamic approach to innovation. Furthermore, the study highlights the interplay between open innovation and organizational agility, demonstrating that it is essential to organizational agility in today’s rapidly changing business world [60]. It further infers that by leveraging external and internal knowledge, companies can respond quickly to technological changes, changing customer requirements, and competition [61].

The study also underscores the mediating role of digital transformation and open innovation in linking knowledge sharing to organizational agility. Sequential mediation analysis reveals that knowledge-sharing practices indirectly enhance agility by supporting digital adoption and innovation processes, forming a continuous cycle of improvement and adaptability [51]. This insight advances the existing literature by demonstrating that organizations that prioritize knowledge exchange are better positioned to leverage digital technologies and innovation as mechanisms for sustaining agility in evolving market landscapes [54,55]. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how knowledge-sharing cultures create long-term competitive advantages through enhanced technological adaptability and innovation-driven agility [119].

The study highlighted that transformational leadership is critical in driving digital transformation, as it persuades employees to innovate and adapt to change in the culture [43,86]. The findings imply that while transformational leadership is vital in enabling digital change [85], excessive influence may dampen the decentralized and collaborative dynamics essential to open innovation [88]. In this respect, firms should aim for leadership approaches that complement, not overshadow, their digital capabilities.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Theoretical Implications

Our research has contributed to the knowledge-based view [31], dynamic capabilities view [32], and transformational leadership theory [87], and to the literature on knowledge management, open innovation, transformational leadership, and organizational agility, considering the context of digital transformation.

First, the results extend the scope of the knowledge-based view [31,46] by proving that knowledge sharing is a supporting mechanism and a strategic facilitator of digital transformation and open innovation [12,72]. Past studies have tended to study these constructs in isolation [120,121]; our proposed framework integrates them to demonstrate how knowledge sharing triggers digital transformation abilities, which subsequently facilitate organizations to reach out for and co-create knowledge outside, thereby achieving open innovation. This situates knowledge as a static asset and a dynamic catalyst for change and flexibility [28].

Second, this research contributes to the existing body of literature on open innovation by providing empirical validation of the mediating impact of digital transformation. This connection has been frequently proposed in conceptual discussions, yet infrequently tested with empirical models [3,4,5]. Earlier literature (e.g., Berenznoy et al. [72] and Singh et al. [120]) has underscored the significance of investigating internal enablers for open innovation. By locating digital transformation as the mediating construct by which knowledge sharing translates into open innovation, this research fills that void and offers a more processual appreciation of how innovation unfolds in knowledge-rich and digitally advanced environments [76].

Third, our findings also enhance the scope of dynamic capabilities’ theoretical framework [32] by demonstrating how companies develop agility through an evolutionary process of capabilities, knowledge sharing, digital integration, and collaborative innovation [38,39]. This insight adds to the theoretical concept of dynamic capabilities as higher-order routines and empirical understanding of processes through which they emerge and strengthen one another.

Fourth, the findings enrich the literature on transformational leadership by validating its moderating role in the relationship between digital transformation and open innovation. Despite being popularly associated with change in organizations and individuals, minimal scholarly work has given thought to its boundary-spanning capabilities as it supports innovation during the digital era [122]. The study offers more critical knowledge on how leadership’s role enhances digital absorptive capacity and cross-boundary cooperation, especially under the pressures of digital transformation [75,86]. It enhances leadership theory by incorporating insights from the domains of innovation and technology management, underscoring the necessity for comprehensive perspectives in forthcoming research [42].

Lastly, the proposed serial mediation model between knowledge sharing and organizational agility through digital transformation and open innovation is a rare contribution to the innovation management and organizational agility literature. In contrast to extant models that conceptualize the constructs linearly, our model emphasizes their interdependence and sequential order of capabilities. Such a formulation is another strong contribution to the current debate on how companies can convert their intangible assets to become agile, resilient, and innovation-oriented in fast-paced environments [123,124].

5.1.2. Practical Implications

There are several actionable insights from our research, which are given below.

First, companies, SMEs in particular, are suggested to promote a culture of knowledge sharing in a systematic manner, which enables free-flowing communication across firm levels and functions. This requires investment in collaborative technology (e.g., communication tools, intranet platforms, and knowledge management systems) that supports formal and informal knowledge exchange. Additionally, SMEs are suggested to consider implementing an incentive system that motivates employees to contribute, reuse, and share organizational knowledge assets.

Second, findings suggest that firms can benefit from strategic investments in digital infrastructure that improve the integration and utilization of shared knowledge. Emerging technologies, like artificial intelligence, cloud-based platforms, and real-time analytics, facilitate decision-making, enable rapid configuration of operations, and enhance open innovation collaboration with external partners. Aligning these emerging technologies with the innovation goals of SMEs helps extend ideation beyond organizational boundaries and strengthen the innovation ecosystem.

Third, the results suggest that the formation and fostering of leadership are essential elements of digital transformation strategies. It is recommended that managers who demonstrate transformational leadership behaviors, comprising a clear digital vision, fostering psychological safety, and empowering teams, are better able to drive digital change and motivate employees towards innovation, even in uncertain situations. Creating training and development that builds such capabilities develops conditions that favor experimentation and agility.

Last, organizations are suggested to consider organizational agility a dynamic capability that necessitates ongoing reinforcement and evaluation. Managers are advised to constantly and periodically scan in-house procedures, labor flexibility, and innovation networks in order to stay ahead of the competition. Agility needs to be considered a continuous process to conform to changing technology and market conditions.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Our work is not without limitations. One key constraint is its reliance on a quantitative survey-based approach conducted within SME settings. While this method captures broad patterns, it may not sufficiently reflect the intricate, context-specific mechanisms through which knowledge sharing fosters innovation and agility. The absence of qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews or case studies, limits the study’s ability to provide a richer, more nuanced understanding of the underlying processes. Future research should incorporate mixed-method approaches to offer deeper insight into how digital transformation unfolds across diverse organizational contexts.

Another limitation arises from the study’s sectoral focus on industrial SMEs, which, while knowledge-intensive, may not be representative of other industries where digital transformation encounters distinct structural and operational challenges. For example, education, healthcare, and technology sectors may exhibit different dynamics in leadership, collaboration, and agility. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings remains uncertain. Future research should extend the investigation across multiple industries to determine whether the observed relationships hold in varying organizational environments.

Furthermore, the study primarily positions transformational leadership as a moderating factor. Yet, other leadership styles, such as servant or transactional, may also play significant roles in shaping digital transformation and innovation. While transformation leadership is widely recognized for fostering adaptability and vision-driven change, leadership effectiveness is often contingent on organizational culture and strategic goals. Future studies should undertake comparative analyses of different leadership styles to ascertain their relative influence on knowledge sharing, innovation adoption, and organizational agility.

Moreover, the research omitted control variables from the structural equation model. Although we took this approach to prioritize the conceptual framework’s focal constructs, we recognize that the exclusion of controls (e.g., firm size, industry type, and digital maturity) could restrict the validity of causal inference. Future research should address the inclusion of relevant control variables to reduce contextual variation and enhance model estimation robustness.

Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design limits its ability to capture the evolving nature of organizational agility. Agility is not a static attribute but a dynamic capability that develops over time in response to technological advancements and market fluctuations. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine how agility co-evolves with digital transformation and whether sustained knowledge-sharing practices enhance an organization’s adaptive capacity in the long run. Furthermore, investigating mediating and moderating variables, such as organizational culture, employee engagement, and technological readiness, would provide a more holistic view of the factors driving successful digital transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and Y.Z.; Data curation, A.B. and S.D.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z.; Investigation, A.B. and Y.Z.; Methodology, S.D.; Project administration, Y.Z.; Resources, Y.Z.; Software, A.B. and S.D.; Supervision, Y.Z.; Writing—original draft, A.B. and S.D.; Writing—review & editing, A.B. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is not supported by any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendation of the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct by the American Psychological Association (APA). Additionally, the study was approved by the ethical committee of the School of Management at Jiangsu University, China, with ethical approval number JU-ECSM-23-0022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests or conflicts of interest.

References

- Navimipour, N.J.; Charband, Y. Knowledge sharing mechanisms and techniques in project teams: Literature review, classification, and current trends. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zighan, S. Disruptive Technology from an Organizational Management Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Business Analytics for Technology and Security (ICBATS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 16–17 February 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Arancibia, J.; Hochstetter-Diez, J.; Bustamante-Mora, A.; Sepúlveda-Cuevas, S.; Albayay, I.; Arango-López, J. Navigating Digital Transformation and Technology Adoption: A Literature Review from Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yu, M.; Chen, P. Navigating Digital Transformation and Knowledge Structures: Insights for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 16311–16344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Prügl, R. Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.; Bou Zakhem, N.; Baydoun, H.; Daouk, A.; Youssef, S.; El Fawal, A.; Elia, J.; Ashaal, A. Toward Digital Transformation and Business Model Innovation: The Nexus between Leadership, Organizational Agility, and Knowledge Transfer. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Antunes Marante, C. A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: Insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1159–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ghrbeia, S.; Alzubi, A. Building micro-foundations for digital transformation: A moderated mediation model of the interplay between digital literacy and digital transformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adobor, H.; Kudonoo, E.C. Antifragility and organizations: An organizational design perspective. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2025, 46, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacavém, A.; de Bem Machado, A.; dos Santos, J.R.; Palma-Moreira, A.; Belchior-Rocha, H.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Leading in the Digital Age: The Role of Leadership in Organizational Digital Transformation. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R. A conceptual model of knowledge sharing. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2020, 10, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silfia, A.; Purwono, R.; Herachwati, N. Knowledge Sharing: Antecedent and Consequences Literature Review. RSF Conf. Ser. Bus. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnik, N.; Yadav, A.; Sahana, B.; Kandhari, H.; Banerjee, S. A survey of analyzing organizational performance and survival employing the management of knowledge. Multidiscip. Rev. 2023, 6, e2023ss089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.P. Emerging technologies: Factors influencing knowledge sharing. World J. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalicchio, A.; Ardito, L.; Savino, T.; Albino, V. Managing knowledge assets for open innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Sánchez-García, E.; Marco-Lajara, B. Open Innovation Strategies for Effective Competitive Advantage; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, H.; Xiao, J. How organizational agility promotes digital transformation: An empirical study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumkale, İ. Organizational Agility. In Organizational Mastery: The Impact of Strategic Leadership and Organizational Ambidexterity on Organizational Agility; Kumkale, İ., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, S.; Enggarsyah, D.T.P. Absorptive capacity, organizational creativity, organizational agility, organizational resilience and competitive advantage in disruptive environments. J. Strategy Manag. 2025, 18, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Kim, S.W. The Impact of IT Capabilities on Organizational Agility with the Moderating Effect of Organizational Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 30915–30935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abro, Q.-U.-A.; Laghari, A.A.; Yin, J.; Qasim, M.; Hussain, A.; Soomro, A.; Hisbani, F.; Ashraf, A. Obligation to Opportunity: Exploring the Symbiosis of Corporate Social Responsibility, Green Innovation, and Organizational Agility in the Quest for Environmental Performance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, S.; Salehi, M.; ArminKia, A.; Novakovic, V. The mediating effect of innovative performance on the relationship between the use of information technology and organizational agility in SMEs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probojakti, W.; Utami, H.N.; Prasetya, A.; Riza, M.F. Building Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Banking through Organizational Agility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, N.A.; Mann, L. Transformational leadership and shared values: The building blocks of trust. J. Manag. Psychol. 2004, 19, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Akdemir, M.A.; Kara, A.U.; Sagbas, M.; Sahin, Y.; Topcuoglu, E. The Mediating Role of Green Innovation and Environmental Performance in the Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, B. The Interplay of Digital Transformational Leadership, Organizational Agility, and Digital Transformation. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 4408–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, K.; Agina, M.F.; Khairy, H.A.; Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Farrag, D.A.; Abdallah, R.M. The effect of electronic human resource management systems on sustainable competitive advantages: The roles of sustainable innovation and organizational agility. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Dong, M.; Guo, H.; Peng, W. Empowering resilience through digital transformation intentions: Synergizing knowledge sharing and transformational leadership amid COVID-19. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2024, 38, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Siddiqui, F.; Magni, D. Senior management’s sustainability commitment and environmental performance: Revealing the role of green human resource management practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8965–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Siddiqui, F.; Wu, Q. The effect of environmental ethics and spiritual orientation on firms’ outcomes: The role of senior management orientation and stakeholder pressure. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership: Good, better, best. Organ. Dyn. 1985, 13, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, V.A.; Lin, C.-Y. Exploring the Determinants of Digital Transformation Adoption for SMEs in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Omoush, K.; Lassala, C.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. The role of digital business transformation in frugal innovation and SMEs’ resilience in emerging markets. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2025, 20, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsaeed, R.H.; Yousaf, Z.; Grigorescu, A.; Samoila, A.; Chitescu, R.I.; Nassani, A.A. Knowledge Sharing Key Issue for Digital Technology and Artificial Intelligence Adoption. Systems 2023, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jabri, M.A.; Shaloh, S.; Shakhoor, N.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Obeidat, B.Y. The impact of dynamic capabilities on enterprise agility: The intervening roles of digital transformation and IT alignment. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedimoghadam, M.; Mira da Silva, M.; Amaral, M. Organizational capabilities for digital innovation: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. The Role of Transformational Leadership in Organizational Innovation. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2025, 18, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunoğlu, A.E.; Şahin, F.; Babacan, S. Transformational leadership, trust, and follower outcomes: A moderated mediation model. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 370–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Chow, C.; Wu, A. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachugu, E. The Role of Transformational Leadership on Digital Innovation and Performance in Large Organizations. J. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 7, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X. Examining the influence of knowledge transfer and dynamic capabilities on enterprise digital transformation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H.K. Knowledge Sharing among Employees in Organizations. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2019, 8, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hummel, J.T.; Nandhakumar, J. A Knowledge-Based Perspective on Digital Transformation. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2023, 2023, 18402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewapatarakul, D.; Ueasangkomsate, P. Digital Organizational Culture, Organizational Readiness, and Knowledge Acquisition Affecting Digital Transformation in SMEs from Food Manufacturing Sector. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241297405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwogwugwu, N.O. Digital Literacy, Creativity, Knowledge Sharing and Dissemination in the 21st Century. In Digital Literacy, Inclusivity and Sustainable Development in Africa; Asamoah–Hassan, H., Ed.; Facet: London, UK, 2022; pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Yin, H.; Liu, X. Coopetition, organizational agility, and innovation performance in digital new ventures. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.M. Digital Transformation and Innovation: Driving Business Growth. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 10, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Chi, M.; Li, Y. Collaborative innovation capability in IT-enabled inter-firm collaboration. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 2364–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Qalati, S.A.; Tajeddini, K.; Wang, H. The impact of artificial intelligence adoption on Chinese manufacturing enterprises’ innovativeness: New insights from a labor structure perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 849–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Mu, X.; Tao, N.; Yin, S. The coupling mechanism of the digital innovation ecosystem and value co-creation. Adv. Environ. Eng. Res. 2023, 4, 013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohman, M.K.; Dawson, G.S.; Desouza, K.C. Digitalization and Sustainability: Advancing Digital Value; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Rodriguez, K.L.; Moran-Murillo, P.N.; Ríos-Gaibor, C.G. Transformación digital y su impacto en estrategias y herramientas tecnológicas en la administración moderna. Multidiscip. Collab. J. 2024, 2, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xingtong, C.; Chen, J. Effect of digital transformation on open innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Qu, G. How to promote open innovation in restricted situations? Digital transformation perspective. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 4615–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Koo, I.; Sadoi, Y.; Pyka, A. Open innovation and digital transformation in the automotive industry: A comparative analysis of South Korea, Japan and Germany. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Z.P. Importance of Agility and Innovation Potential in Business: Transforming Organizational Structures and Processes. In Business Transformation in the Era of Digital Disruption; Taherdoost, H., Drazenovic, G., Madanchian, M., Khan, I.U., Arshi, O., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Arnett, D.B.; Hou, L. Using external knowledge to improve organizational innovativeness: Understanding the knowledge leveraging process. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, S.; Demir, R.; Eldridge, S. A microfoundational view of the interplay between open innovation and a firm’s strategic agility. Long Range Plan. 2024, 57, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, A.-K.; Hagedoorn, J. Implications of Open Innovation for Organizational Boundaries and the Governance of Contractual Relations. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 34, 400–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Iwao, S. Pure Dynamic Capabilities to Accomplish Economies of Growth. Ann. Bus. Adm. Sci. 2016, 15, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo Fernandez, J.C.; Martinez Moreno, O.C.; Rodriguez Arias, C.A. Capacidades dinámicas: Reflexión teórica desde el campo de la estrategia. Publ. Investig. 2023, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urresta-Vargas, D.; Carvajal-Vargas, V.; Arias-Pérez, J. Dismissing uncertainties about open innovation constraints to organizational agility in emerging markets: Is knowledge hiding a perfect storm? Manag. Decis. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmerón, J.P.; Valle, R.S.; Molina-Castillo, F.-J. Beyond borders: Unraveling the tapestry of export performance through business model innovation, open innovation, and organisational agility. Technovation 2025, 144, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokter, H.; Astrid Heidemann, L. Q&A. How Do Digital Platforms for Ideas, Technologies, and Knowledge Transfer Act as Enablers for Digital Transformation? Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2017, 7, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayaka, S.P. Knowledge co-creation in the digital age: Social Science research as a catalyst. Sri Lanka J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 46, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Qinghao, W.; Liu, J. Nonlinear nexus among business environment, digital transformation and ESG performance of private enterprises in China: New insights from mediation-threshold models. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Galati, F.; Gastaldi, L. The digitalization of the innovation process. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereznoy, A.; Meissner, D.; Scuotto, V. The intertwining of knowledge sharing and creation in the digital platform-based ecosystem. A conceptual study on the lens of the open innovation approach. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 2022–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, K.; Josserand, E.; Schweitzer, J.; Logue, D. Knowledge collaboration between organizations and online communities: The role of open innovation intermediaries. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1293–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Impact of Digital Technologies on Organizational Change Strategies: A Review. Res. J. Bus. Econ. 2024, 2, 01–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNuaimi, B.K.; Kumar Singh, S.; Ren, S.; Budhwar, P.; Vorobyev, D. Mastering digital transformation: The nexus between leadership, agility, and digital strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, Y. The use of data-driven insight in ambidextrous digital transformation: How do resource orchestration, organizational strategic decision-making, and organizational agility matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 196, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.R.D.O.; Gonçalo, C.R.; Santos, A.M. Digital transformation with agility: The emerging dynamic capability of complementary services. RAM. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2022, 23, eRAMD220063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, B.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Jalal, A.; Suboktagin, S.; Elboughdiri, N. Sustainable food systems transformation in the face of climate change: Strategies, challenges, and policy implications. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, S.; Nakagawa, K. The interplay of digital transformation and collaborative innovation on supply chain ambidexterity. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riel, A.; Messnarz, R.; Woeran, B. Democratizing innovation in the digital era: Empowering innovation agents for driving the change. In Proceedings of the Systems, Software and Services Process Improvement: 27th European Conference, EuroSPI 2020, Düsseldorf, Germany, 9–11 September 2020; pp. 757–771. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, L.T. Organisational ambidexterity and supply chain agility: The mediating role of external knowledge sharing and moderating role of competitive intelligence. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2016, 19, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, J. How digital transformation enhances corporate innovation performance: The mediating roles of big data capabilities and organizational agility. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, A.; Keswani, B.; Mohanty, S.K.; Mohapatra, A.G.; Nayak, S.; Akhtar, M.M. Synergizing Knowledge Management in the Era of Industry 4.0: A Technological Revolution for Organizational Excellence. In Knowledge Management and Industry Revolution 4.0; Wiley-Scrivener: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 39–85. [Google Scholar]

- Marjerison, R.K.; Andrews, M.; Kuan, G. Creating sustainable organizations through knowledge sharing and organizational agility: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saefullah, A.; Hidayatullah, S.; Fadli, A.; Candra, H. The impact of transformational leadership on energy innovation: A review from the viewpoint of the consumer. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2024, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgiseven, E.B. Transformational and Digital Leadership for Digital Transformation in the Digital Age. In Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management for Complex Work Environments; Belias, D., Rossidis, I., Papademetriou, C., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. Transformational leadership theory. In Organizational Behavior 1; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 361–385. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, I.W.K.; Sui, H.J.; Kweh, Q.L.; Nawanir, G. Knowledge management and firm innovative performance with the moderating role of transformational leadership. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 2115–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehalwar, K.; Sharma, S.N. Exploring the distinctions between quantitative and qualitative research methods. Think India J. 2024, 27, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Qalati, S.A. Linking managerial ties and organizations sustainability outcomes via knowledge management and business model innovation: The role of environmental turbulence. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qalati, S.A.; Fan, M. Effects of sustainable innovation on stakeholder engagement and societal impacts: The mediating role of stakeholder engagement and the moderating role of anticipatory governance. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2406–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasius, J.; Brandt, M. Representativeness in Online Surveys through Stratified Samples. Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 2010, 107, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C. Motivated to share? Development and validation of a domain-specific scale to measure knowledge-sharing motives. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2024, 54, 861–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Curado, C.M.M.; Maçada, A.C.G.; Nodari, F. Using alternative scales to measure knowledge sharing behavior: Are there any differences? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-P.; Chou, C. The impact of open innovation on firm performance: The moderating effects of internal R&D and environmental turbulence. Technovation 2013, 33, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimo-Metcalfe, B.; Alban-Metcalfe, R.J. The development of a new Transformational Leadership Questionnaire. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2001, 74, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Badwy, H.E.; El-Bardan, M.F. Career Proactivity Unleashed: Charting the Path to Sustainable Success Through the Art of Self-Regulated Learning. J. Employ. Couns. 2025, 62, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Yoon, H.J. Personality psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, H.; Rahman, A.; Azim, J.A.; Memon, W.H.; Qian, L. Structural equation model of young farmers’ intention to adopt sustainable agriculture: A case study in Bangladesh. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hancock, G.R. A structural equation modeling approach for modeling variability as a latent variable. Psychol. Methods 2024, 29, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q. Impact of digital transformation in agribusinesses on total factor productivity. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2024, 27, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ygnacio, M.A.C. Digital transformation in universities: Models, frameworks and road map. Int. J. Electron. Gov. 2024, 16, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautela, S. Open innovation and new product development: Major themes and research trajectories. J. Manag. Hist. 2024, 30, 686–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budur, T.; Demirer, H.; Rashid, C.A. The effects of knowledge sharing on innovative behaviours of academicians; mediating effect of innovative organization culture and quality of work life. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2024, 16, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Qi, Y.; Hao, S. Enhancing innovation performance of SMEs through open innovation and absorptive capacity: The moderating effect of business model. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 2907–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cricchio, J.; Di Minin, A. The rise of open innovation in Chinese academia: A systematic review of the literature. RD Manag. 2024, 55, 899–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasnacht, D. Open Innovation as a Basis. In Open and Digital Ecosystems; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Minhaj, S.M.; Khan, M.A. Dimensions of E-Banking and the mediating role of customer satisfaction: A structural equation model approach. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2025, 36, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W.; Appleyard, M.M. Open Innovation and Strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 50, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-S.; Tseng, C.-W. Digital transformation anxiety: Absorptive capacity, dynamic capability, and digital innovation performance. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 734–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, B.; Piccarozzi, M.; Abbate, T.; Codini, A. The Role of Open Innovation and Value Co-creation in the Challenging Transition from Industry 4.0 to Society 5.0: Toward a Theoretical Framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Adner, R. What Firms Make vs. What They Know: How Firms’ Production and Knowledge Boundaries Affect Competitive Advantage in the Face of Technological Change. Organ. Sci. 2011, 23, 1227–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Zhiying, L.; Ma, C. Direct and configurational paths of open innovation and organisational agility to business model innovation in SMEs. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egodawele, M.; Sedera, D.; Bui, V. A Systematic Review of Digital Transformation Literature (2013–2021) and the development of an overarching apriori model to guide future research. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.03867. [Google Scholar]

- Marhraoui, M.A.; Manouar, A.E. Towards a new framework linking knowledge management systems and organizational agility: An empirical study. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.08182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Busso, D.; Kamboj, S. Top management knowledge value, knowledge sharing practices, open innovation and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Pereira, M.S.; Sá, J.C.; Powell, D.J.; Faria, S.; Magalhães, M. Digital Culture, Knowledge, and Commitment to Digital Transformation and Its Impact on the Competitiveness of Portuguese Organizations. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J. Viewing Digital Transformation through the Lens of Transformational Leadership. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2021, 31, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Çemberci, M. Understanding the relationships among knowledge-oriented leadership, knowledge management capacity, innovation performance and organizational performance. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 2819–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Masood, A. Impact of digital leadership on open innovation: A moderating serial mediation model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).