Small-Scale Farming in the United States: Challenges and Pathways to Enhanced Productivity and Profitability

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- Retirement farms—those whose principal operators report that they are retired but farm on a small scale.

- ii.

- Off-farm occupation—here, farming is not the primary occupation of the principal operators. They include those whose operators do not consider themselves to be in the labor force.

- iii.

- Farming-occupation farms—here, the primary occupation of principal operators is farming. This one is further divided into two.

- ❖

- Low sales—farms generating GCFI of less than USD150,000.

- ❖

- Moderate sales—farms generating GCFI of between USD150,000 and USD349,999.

2. Challenges Facing Small-Scale Farms in the U.S.

2.1. Social Challenges

2.1.1. Off-Farm Work as a Challenge

2.1.2. Gender as a Challenge

2.1.3. Personal Challenges

2.2. Economic Challenges

2.2.1. Access to Farmland

2.2.2. Access to Credit and Capital

2.2.3. Competition from Corporations

2.2.4. Availability of Scale

2.2.5. Misconception of Import Substitution

2.3. Climate Change and Other Environmental Uncertainties

2.4. Institutional and Technological Challenges

2.4.1. Lack of Knowledge and Skills

2.4.2. Difficulties to Insure

2.4.3. Disadvantages in Technology Adoption

2.4.4. Alienation from Mainstream Agricultural Activities

2.5. Socio-Psychological Challenges for Small-Scale Farming in the US

- (i)

- Financial stress—small-scale farmers often operate on tight profit margins [14]. The combined pressures of unpredictable market prices and rising operational costs can lead to considerable stress and economic hardship for farmers.

- (ii)

- Social and emotional isolation—farmers often work for long hours alone. Several studies have found that farmers’ lack of social connection can have severe negative consequences for their mental well-being, leading to a greater risk of developing stress, anxiety, and depression [96].

- (iii)

- Limited access to healthcare—this mostly affects individuals in geographically isolated rural areas, where access to mental healthcare can be challenging [97]. Due to the stigma surrounding mental health concerns, farmers often hesitate to seek mental health assistance thereby increasing their levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.

- (iv)

- Identity and purpose—farmers often derive a strong sense of purpose and pride from their work. However, evolving societal perceptions and media misrepresentations pose a threat to this feeling of identity and purpose [98]. The falsified identity information can bring socio-psychological distress among the farming community [93,94].

- (v)

- Work–life balance and family strain—farm work demands can make it difficult for farmers to maintain a healthy work–life balance [99]. This can put a strain on relationships within farm families, leading to complex stresses that negatively affect their overall well-being.

- (vi)

- Competition and market access—small-scale farms struggle to compete with large-scale operations because of economies of scale and lack of resources [68]. This adds to their economic stress and uncertainty.

- (vii)

- Succession planning—small-scale farms are often characterized by multi-generational nature [22]. Thus, they are prone to tensions associated with farm management, decision making, and the farm’s transfer to the next generation.

3. Pathways for Enhancing Productivity and Profitability

3.1. Social Leveraging Opportunities

3.1.1. Lifestyle Farming

- i.

- Contribute significantly to the multifunctional transitions in the areas they invest in.

- ii.

- Pursue environmentally focused lifestyles and may engage in farm tourism.

- iii.

- Help maintain agricultural landscapes in the high-quality farmlands that are fragmented as a result of urban sprawls.

- iv.

- Their presence can create value-based linkages in their communities.

3.1.2. Local Food Movements and Social Capital

- i.

- Organizing information flow and resource utilization within their communities. These can influence farmer actions.

- ii.

- Promoting alternative models of farming and offering training opportunities to aspiring farmers [32].

- iii.

- Strengthening communities, enhancing trust, and fostering cooperation between producers and consumers [107].

- iv.

- Creating a virtuous cycle of social capital encourages communities to address local concerns [108].

3.1.3. Increasing Consumer Demand

3.1.4. Local Food Security Needs

3.2. Growing Consumer Interest in Healthy Foods

3.3. Leveraging Stewardship Ethics

3.3.1. Women in Agriculture

3.3.2. Youth and Beginner Farmers

3.3.3. Scale of Operations

3.4. Annexing Technology

3.5. Development of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture (UPA)

3.6. Marketing Strategies and Institutional Pathways

3.6.1. Direct Marketing

3.6.2. Value Addition

3.6.3. Food Safety Requirements

3.6.4. Product Labeling

3.6.5. Agrotourism

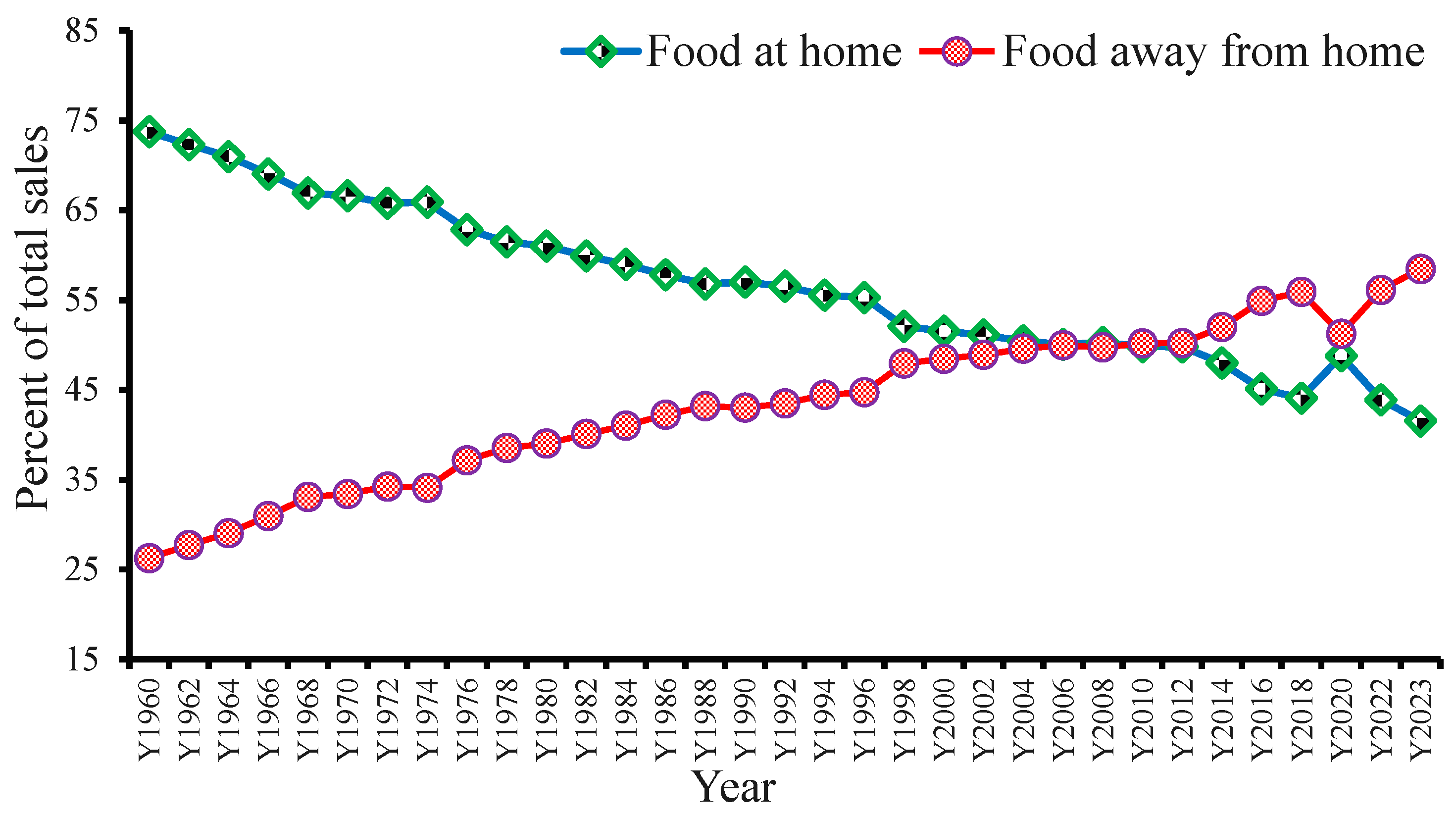

3.6.6. Food Away from Home Opportunities

3.6.7. Product and Farm Diversification

3.7. Regenerative and Organic Farming Opportunities for Small-Scale Farmers

3.8. Institutional Opportunities

3.8.1. Forming Cooperatives

3.8.2. Political, Economic, and Social Empowerment

3.8.3. Government Support Schemes

3.8.4. Land Grant University Extension and Research Services

3.9. Pathways to Ameliorate Socio-Psychological Stressors

- (i)

- Strong sense of community and belonging—small farms can be integral to strengthening local communities. Through local food systems, they foster a sense of belonging and connectedness among farmers and consumers [107]. Further, farmer networks offer opportunities to exchange information, share experiences, and build supportive relationships [83].

- (ii)

- Mental health awareness and support programs—many organizations, including federal, state and local government agencies, land grant universities, etc., are working to raise awareness about mental health challenges in farming communities [177]. They intend to achieve these by continuous development of specialized resources and support programs that address their unique needs [177].

- (iii)

- Connecting with nature—farming offers a direct connection to nature’s therapeutic benefits that have been associated with reduced stress, better mental health, and increased mindfulness and purpose [178].

- (iv)

- Direct marketing and local food systems—small farms thrive by directly marketing their products to consumers through farmers’ markets, CSA programs, and farm-to-table initiatives. These avenues often foster strong relationships and a sense of togetherness among community members [85].

- (v)

- Educational and research initiatives—recent years have seen increased efforts to address the lack of awareness and educational resources among small-scale farmers. Growing attention is being paid to farmer mental health research, driven by the need to understand their distinct challenges and design effective support solutions [177].

| Program | Description | How It Supports Small and Beginning Farms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct farm ownership loans | Provides loans of up to USD600,000 to purchase farmland or build structure | Enables small farmers to purchase land with minimum down payment and lower interest rates | [179] |

| Direct operating loans | Provides loans of up to USD400,000 to purchase equipment, seed, livestock, etc. | Enables starting and maintaining a farm by providing affordable startup capital and production costs | [179] |

| Guaranteed loans | Private loans guaranteed by USDA | Improves access to credit by reducing lender risk. | [179] |

| Down payment loan program | Provides loan to purchase land through FSA and private funding | Excellent tool for land access since it requires only 5% downpayment. | [179] |

| Federal crop insurance | Covers loss of yield, revenue, or quality for eligible crops | Provides income protection against natural disasters and price drops | [171,179] |

| EQIP (Environmental Quality Incentives Program) | Cost-share program to implement conservation practices | Covers a % of producer cost for practices like fencing, irrigation, cover crops, high tunnels, etc. | [180] |

| CSP (Conservation Stewardship Program) | Rewards ongoing stewardship and advanced conservation in lands | Pays annually for the maintenance and improvement of practices that promote continuous improvement | [180] |

| REAP (Rural Energy for America Program) | Loans and grants guaranteed to help farmers and rural small businesses | Provides farmers with an opportunity to implement energy efficiency projects on their farms. | [181] |

| VAPG (Value-Added Producer Grant) | Cost-share program that provides capital grants | Provides grants for value-added activities like generating new products, creating and expanding markets. | [181] |

| SNAP Healthy Incentives | Provides coupons, discounts, gift cards, bonus food items, or extra funds to purchase healthy foods. | Connects small farm producers to SNAP authorized retailers. Incentivizes fruit and vegetable farming | [182] |

| Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program | Provides low-income seniors with access to locally grown fruits, vegetables, honey, and herbs. | The use of farmers’ markets, roadside stands, and community support agricultural programs provide market for small producers. | [182] |

| WIC Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program | Provides locally grown fruits, vegetables, and herbs through farmers’ markets and roadside stands for WIC participants. | The use of farmers’ markets, roadside stands, and community support agricultural programs provide market for small producers. | [182] |

| The Patrick Leahy Farm to School Program | Increases the availability of local foods in schools. | Expands markets for small producers. Trains local producers on how to sell foods to local schools. | [182] |

3.10. Targeted Solutions for Small-Scale Farm Sustainability and Growth

4. Implications for Application, Policy Formulation, Research, and Extension

4.1. Enhanced Clarity on Definition of a Small Farm

4.2. Enhanced Product Marketability

4.3. Increased Awareness of Available Policies and Programs

4.4. Mechanisms to Provide Dependable Labor

4.5. Enhanced Risk Management and Business Planning Tools

4.6. Ensure Smallholder-Friendly Financing

- (i)

- Making collaterals flexible by, for example, using crop inventories;

- (ii)

- Developing mechanisms to easily identify borrowers, e.g., use of credit bureaus;

- (iii)

- Synchronizing loan repayment plans with agricultural seasonality;

- (iv)

- Encouraging them to take more risks by integrating weather-based insurance together with credit.

4.7. Recruitment of Younger Farmers

4.8. Linking Agricultural Production to Nutrition and Health

4.9. Promoting Pro-Small-Scale Farmer Value Chains

4.10. Investing in Agricultural Research, Technology, and Extension Services

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFN | Alternative Food Networks |

| BFRDP | Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program |

| CSA | Community Supported Agriculture |

| ERS | Economic Research Service |

| FAFH | food away from home |

| FAT | food at home |

| FSA | Farm Service Agency |

| FSMA | Food Safety Modernization Act |

| GCFI | Gross Cash Farm Income |

| NASS | National Agricultural Statistics Service |

| SARE | Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education |

| UPA | urban and peri-urban agriculture |

| U.S. | United States of America |

| USDA | U.S. Department of Agriculture |

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; ST/ESA/SER.A/423; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manono, B.O.; Moller, H.; Benge, J.; Carey, P.; Lucock, D.; Manhire, J. Assessment of soil properties and earthworms in organic and conventional farming systems after seven years of dairy farm conversions in New Zealand. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 43, 678–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2020. In Overcoming Water Challenges in Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Mehrabi, Z.; Jarvis, L.; Chookolingo, B. How much of the world’s food do smallholders produce? Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vávra, J.; Megyesi, B.; Duží, B.; Craig, T.; Klufová, R.; Lapka, M.; Cudlínová, E. Food self-provisioning in Europe: An exploration of sociodemographic factors in five regions. Rural. Sociol. 2018, 83, 431–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Thomson, K.J. Family Farming in the Enlarged EU: Concepts, Challenges and Prospects. In the 142nd EAAE Seminar, Proceedings of the ‘Growing Success? Agriculture and Rural Development in an Enlarged EU’, Budapest, Hungary, 29–30 May 2014; Corvinus University of Budapest: Budapest, Hungary, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Persello, C.; Tolpekin, V.A.; Bergado, J.R.; De By, R.A. Delineation of agricultural fields in smallholder farms from satellite images using fully convolutional networks and combinatorial grouping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groher, T.; Heitkämper, K.; Walter, A.; Liebisch, F.; Umstätter, C. Status quo of adoption of precision agriculture enabling technologies in Swiss plant production. Precis. Agric. 2020, 1327, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- György, K.T.; Lámfalusi, I.; Molnár, A.; Sulyok, D.; Gaál, M.; Domán, C.; Illés, I.; Kiss, A.; Péter, K.; Kemény, G. Precision agriculture in Hungary: Assessment of perceptions and accounting records of FADN arable farms. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2018, 120, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamirat, T.W.; Pedersen, S.M.; Lind, K.M. Farm and operator characteristics affecting adoption of precision agriculture in Denmark and Germany. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2018, 68, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Resources for Small and Mid-Sized Farmers. 2025. Available online: https://www.usda.gov/farming-and-ranching/resources-small-and-mid-sized-farmers (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Holland, R.; Khanal, A.R.; Dhungana, P. Agritourism as an alternative on-farm enterprise for small US farms: Examining factors influencing the agritourism decisions of small farms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, R.; Lardon, S.; Bonari, E.; Marraccini, E. Unraveling the contribution of periurban farming systems to urban food security in developed countries. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasswitz, T.R. Integrated pest management (IPM) for small-scale farms in developed economies: Challenges and opportunities. Insects 2019, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay-Palmer, A.; Santini, G.; Dubbeling, M.; Renting, H.; Taguchi, M.; Giordano, T. Validating the city region food system approach: Enacting inclusive, transformational city region food systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P. Five big questions about five hundred million small farms. In Proceedings of the Conference on New Directions for Smallholder Agriculture, Rome, Italy, 24–25 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giller, K.E.; Delaune, T.; Silva, J.V.; Descheemaeker, K.; Van De Ven, G.; Schut, A.G.; Van Wijk, M.; Hammond, J.; Hochman, Z.; Taulya, G.; et al. The future of farming: Who will produce our food? Food Secur. 2021, 3, 1073–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-ERS. Farm Economy: Farm Household Well-Being—Glossary. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being/glossary (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The state of family farms in the world. World Dev. 2016, 87, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A.; Madureira, L.; Dirimanova, V.; Bogusz, M.; Kania, J.; Vinohradnik, K.; Creaney, R.; Duckett, D.; Koehnen, T.; Knierim, A. New knowledge networks of small-scale farmers in Europe’s periphery. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, I.; Berges, R.; Piorr, A.; Krikser, T. Contributing to food security in urban areas: Differences between urban agriculture and peri-urban agriculture in the Global North. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iles, K.; Ma, Z.; Erwin, A. Identifying the common ground: Small-scale farmer identity and community. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 78, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariola, M.; Schwieterman, A.; Desonier-Lewis, G. What do local foods consumers want? Lessons from ten years at a local foods market. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2022, 11, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapsomanikis, G. Small farms big picture: Smallholder agriculture and structural transformation. Development 2015, 58, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, P. Food sovereignty and alternative paradigms to confront land grabbing and the food and climate crises. Development 2011, 54, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-ERS. Farm Economy: Farm Structure and Organization—Farm Structure and Contracting. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-structure-and-organization/farm-structure-and-contracting (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Krebs, A.V. The Corporate Reapers: The Book of Agribusiness; Essential Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen, D.A.; Smith, R.G. Confronting barriers to cropping system diversification. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 564197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, A.C.; Katchova, A.L. How economic conditions changed the number of US Farms, 1960–1988: A replication and extension of Gale (1990) to midsize farms in the United States and abroad. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2023, 45, 1400–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, M.P.; Feindt, P.H.; Spiegel, A.; Termeer, C.J.; Mathijs, E.; De Mey, Y.; Finger, R.; Balmann, A.; Wauters, E.; Urquhart, J.; et al. A framework to assess the resilience of farming systems. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Miranda, D.; Moreno-Pérez, O.; Arnalte-Mur, L.; Cerrada-Serra, P.; Martinez-Gomez, V.; Adolph, B.; Atela, J.; Ayambila, S.; Baptista, I.; Barbu, R.; et al. The future of small farms and small food businesses as actors in regional food security: A participatory scenario analysis from Europe and Africa. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 95, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, A.B. Farm entry and persistence: Three pathways into alternative agriculture in southern Ohio. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 69, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigford, A.A.; Hickey, G.M.; Klerkx, L. Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an agricultural innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions. Agric. Syst. 2018, 164, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, C. A growing number of young Americans are leaving desk jobs to farm. The Washington Post, 23 November 2017, p. 23. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/a-growing-number-of-young-americans-are-leaving-desk-jobs-to-farm/2017/11/23/e3c018ae-c64e-11e7-afe9-4f60b5a6c4a0_story.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Omobitan, O.; Khanal, A.R. Examining farm financial management: How do small US farms meet their agricultural expenses? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubela, H.J. Off-farm income: Managing risk in young and beginning farmer households. Choices 2016, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Quaicoe, O.; Asiseh, F.; Baffoe-Bonnie, A.; Ng’ombe, J.N. Small farms in North Carolina, United States: Analyzing farm and operator characteristics in the pursuit of economic resilience and sustainability. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2024, 46, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, R. Are Small Farms Sustainable by Nature?—Review of an Ongoing Misunderstanding in Agroecology. 2020. Available online: https://scholarworks.montana.edu/handle/1/17267 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Iles, K.; Ma, Z.; Nixon, R. Multi-dimensional motivations and experiences of small-scale farmers. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2021, 34, 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-NASS: Census of Agriculture. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/index.php#full_report (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Rosenberg, N.A. Farmers who don’t farm: The curious rise of the zero-sales farmer. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2017, 7, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, J.N.; Gouldthorpe, J.L. Small farmers, big challenges: A needs assessment of Florida small-scale farmers’ production challenges and Training needs. J. Rural. Soc. Sci. 2013, 28, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Wachenheim, C.J. Technology adoption among farmers in Jilin Province, China: The case of aerial pesticide application. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019, 11, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, C. The Invisible Farmers: Women in Agricultural Production; Rowman & Littlefield Pub Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, J.A. Women farmers in developed countries: A literature review. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Goetz, S.J.; Tian, Z. Female farmers in the United States: Research needs and policy questions. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-NIFA: Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program (BFRDP)—Program Information. Available online: https://www.nifa.usda.gov/grants/programs/beginning-farmer-rancher-development-program-bfrdp (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Mitchell, G.; Currey, R.C. Increasing participation of women in agriculture through science, technology, engineering, and math outreach methods. J. Ext. 2020, 58, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O. Effects of Irrigation, Effluent Dispersal and Organic Farming on Earthworms and Soil Microbes in New Zealand Dairy Farms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2014. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10523/5097 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Anyebe, O.; Sadiq, F.K.; Manono, B.O.; Matsika, T.A. Biochar Characteristics and Application: Effects on Soil Ecosystem Services and Nutrient Dynamics for Enhanced Crop Yields. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.L.; Getz, C. Farm size and job quality: Mixed-methods studies of hired farm work in California and Wisconsin. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.P.; Soto, I.; Eory, V.; Beck, B.; Balafoutis, A.; Sánchez, B.; Vangeyte, J.; Fountas, S.; van der Wal, T.; Gómez-Barbero, M. Exploring the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: A cross regional study of EU farmers. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo, A. How knowledge deficit interventions fail to resolve beginning farmer challenges. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, P. When farmers are pulled in too many directions: Comparing institutional drivers of food safety and environmental sustainability in California agriculture. In Social Innovation and Sustainability Transition; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Manono, B.O. New Zealand dairy farm effluent, irrigation and soil biota management for sustainability: Farmer priorities and monitoring. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1221636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.B.; Oberg, A.; Nelson, L. Rural gentrification and linked migration in the United States. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackoff, S.; Flom, E.; Polanco, V.G.; Howard, D.; Manly, J.; Mueller, C.; Rippon-Butler, H.; Wyatt, L.; Caceres, Y.; West, E.F.; et al. Building a Future with Farmers 2022: Results and Recommendations from the National Young Farmer Survey; Albany, N.Y., Ed.; National Young Farmers Coalition: Albany, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://youngfarmers.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/National-Survey-Web-Update_11.15.22-1.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dodson, C.B.; Ahrendsen, B.L. Farm and lender structural change: Implications for federal credit. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, C.; Morehart, M.; Kuethe, T.; Beckman, J.; Ifft, J.; Williams, R. Trends in US Farmland Values and Ownership. In Economic Information Bulletin No. 92; USDA Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/publications/44656/16748_eib92_2_.pdf?v=42118 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Campbell, J.; Riggs, A.N.; Montgomery, D. Using urban farmer perceptions of urban agricultural resources to inform extension programming: AQ methodology study. J. Appl. Commun. 2023, 107, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Hannah, C.; Guido, Z.; Zimmer, A.; McCann, L.; Battersby, J.; Evans, T. Barriers to urban agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 2021, 103, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Yadav, V.K. An integrated literature review on Urban and Peri-urban farming: Exploring research themes and future directions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi-Nezhad, M.; Salehi, R.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Winans, K.S.; Nabavi-Pelesaraei, A. An analysis of energy use and economic and environmental impacts in conventional tunnel and LED-equipped vertical systems in healing and acclimatization of grafted watermelon seedlings. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, A.R.; Omobitan, O. Rural finance, capital constrained small farms, and financial performance: Findings from a primary survey. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, T.G.; Christy, R.D. Structural changes in US agriculture: Implications for small farms. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, L.; De Wit, M.M.; DeLonge, M.S.; Calo, A.; Getz, C.; Ory, J.; Munden-Dixon, K.; Galt, R.; Melone, B.; Knox, R.; et al. Securing the future of US agriculture: The case for investing in new entry sustainable farmers. Elem. Sci. Anth 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, B.B.; Key, N.; Hadrich, J.; Bauman, A.; Campbell, S.; Thilmany, D.; Sullins, M. Opportunities to support beginning farmers and ranchers in the 2023 Farm Bill. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 44, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, S.; Rhyne, M.; Dery, N. Lessons learned from advocating CSAs for low-income and food insecure households. J. Rural. Soc. Sci. 2008, 23, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Grasswitz, T.R.; Yao, S. Efficacy of pheromonal control of peachtree borer (Synanthedon exitiosa (Say)) in small-scale orchards. J. Appl. Entomol. 2016, 140, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, L. The city in the country: Growing alternative food networks in Metropolitan areas. J. Rural. Stud. 2008, 24, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, L.A.; Lutz, B.; Doyle, M.W. Climate and direct human contributions to changes in mean annual streamflow in the South Atlantic, USA. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 7278–7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, A. Predicting the interaction between the effects of salinity and climate change on crop plants. Sci. Hortic. 1998, 78, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O.; Khan, S.; Kithaka, K.M. A Review of the Socio-Economic, Institutional, and Biophysical Factors Influencing Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Climate Smart Agricultural Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa. Earth 2025, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walthall, C.L.; Hatfield, J.; Backlund, P.; Lengnick, L.; Marshall, E.; Walsh, M.; Adkins, S.; Aillery, M.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Ammann, C.; et al. Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States: Effects and Adaptation; USDA Technical Bulletin 1935: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; p. 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, A.S.; Newton, P.; Gil, J.D.; Kuhl, L.; Samberg, L.; Ricciardi, V.; Manly, J.R.; Northrop, S. Smallholder agriculture and climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagata, L.; Sutherland, L.A. Deconstructing the ‘young farmer problem in Europe’: Towards a research agenda. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 38, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, P.; Galli, F.; Moreno-Pérez, O.M.; Chiffoleau, Y.; Grando, S.; Karanikolas, P.; Rivera, M.; Goussios, G.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Brunori, G. Disentangling the diversity of small farm business models in Euro-Mediterranean contexts: A resilience perspective. Sociol. Rural. 2023, 63, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, N.A.; Stankovics, P.; Jarvis, R.M.; Morris-Trainor, Z.; de Vries, J.R.; Ingram, J.; Mills, J.; Glikman, J.A.; Parkinson, J.; Toth, Z.; et al. Have farmers had enough of experts? Environ. Manag. 2022, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.; Roberts, R. A Historical Examination of Food Labeling Policies and Practices in the United States: Implications for Agricultural Communications. J. Agric. Educ. 2022, 63, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, A.; Swisher, M.E.; Chase, C.A.; Irani, T.; Ruiz-Menjivar, J. The Roots of First-Generation Farmers: The Role of Inspiration in Starting an Organic Farm. Land 2023, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.A. Expanding technical assistance for urban agriculture: Best practices for extension services in California and beyond. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2011, 1, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarthe, P.; Laurent, C. Privatization of agricultural extension services in the EU: Towards a lack of adequate knowledge for small-scale farms? Food Policy 2013, 38, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J.C.; Keay, J. Farming practices, knowledge, and use of integrated pest management by commercial fruit and vegetable growers in Missouri. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2018, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaensen, L.; Rutledge, Z.; Taylor, J.E. The future of work in agri-food. Food Policy 2021, 99, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, O.M.; Arnalte-Mur, L.; Cerrada-Serra, P.; Martinez-Gomez, V.; Adamsone-Fiskovica, A.; Bjørkhaug; Brunori, G.; Czekaj, M.; Duckett, D.; Hernández, P.A.; et al. Actions to strengthen the contribution of small farms and small food businesses to food security in Europe. Food Secur. 2024, 16, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.; Gandorfer, M. Adoption of digital technologies in agriculture—An inventory in a European small-scale farming region. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annosi, M.C.; Brunetta, F.; Monti, A.; Nati, F. Is the trend your friend? An analysis of technology 4.0 investment decisions in agricultural SMEs. Comput. Ind. 2019, 109, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, S.; Gravely, E.; Mosby, I.; Duncan, E.; Finnis, E.; Horgan, M.; LeBlanc, J.; Martin, R.; Neufeld, H.T.; Nixon, A.; et al. Automated pastures and the digital divide: How agricultural technologies are shaping labour and rural communities. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 68, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelpfennig, D.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. 92. Precision agriculture adoption, farm size and soil variability. In Precision Agriculture’21; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 19 July 2021; pp. 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M. Barriers and Drivers Underpinning Newcomers in Agriculture: Evidence from Italian Census Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Miller, S. The impacts of local markets: A review of research on farmers markets and community supported agriculture (CSA). Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Mission, E.G.; Fuaad, A.A.; Shaalan, M. Nanoparticle tools to improve and advance precision practices in the Agrifoods Sector towards sustainability-A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, A.J.; Lim, J.I.; Zhang, Y.; Shelle, G. Factors influencing farmers’ use of adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. J. Agromed. 2023, 28, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett-Wright, D.; Malin, C.; Jones, M.S. Mental health in farming communities. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2023, 61, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iles, K.; Nixon, R.; Ma, Z.; Gibson, K.; Benjamin, T. The motivations, challenges and needs of small- and medium-scale beginning farmers in the midwestern United States. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2023, 12, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stain, H.J.; Kelly, B.; Lewin, T.J.; Higginbotham, N.; Beard, J.R.; Hourihan, F. Social networks and mental health among a farming population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nason, E.E.; Blankenship, A.S.; Benevides, E.; Stump, K. The role of social work in confronting the farmer suicide crisis: Best practice recommendations and a call to action. Soc. Work. Public Health 2023, 38, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, A.M.; Lundy, L.K.; Park, T.D. Glitz, glamour, and the farm: Portrayal of agriculture as the simple life. J. Appl. Commun. 2005, 89, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Gosselin, H.; Grisé, J. Are women owner-managers challenging our definitions of entrepreneurship? An in-depth survey. J. Bus. Ethics 1990, 9, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.L. Hobby farming in America: Rural development or threat to commercial agriculture? J. Rural. Stud. 1986, 2, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.; Stock, P. Repeasantisation in the United States. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 58, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S. Local Food Sales Continue to Grow through a Variety of Marketing Channels. In Amber Waves: The Economics of Food, Farming, Natural Resources, and Rural America; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2021/october/local-food-sales-continue-to-grow-through-a-variety-of-marketing-channels (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- McFadden, D.T. “What Do We Mean by “Local Foods”? Choices.” Quarter 1. 2015. Available online: http://choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/community-economics-of-local-foods/what-do-we-mean-by-local-foods (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Li, T.; Ahsanuzzaman; Messer, K.D. Is This Food “Local?” Evidence from a Framed Field Experiment. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 45, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyson, T.A.; Guptill, A. Commodity agriculture, civic agriculture and the future of US farming. Rural. Sociol. 2009, 69, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-ERS. Farming and farm income. In Ag and Food Statistics: Charting the Essentials; USDA Economic Research Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Glowacki-Dudka, M.; Murray, J.; Isaacs, K.P. Examining social capital within a local food system. Community Dev. J. 2013, 48, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.C.; Lamie, D.; Stickel, M. Local foods systems and community economic development. In Local Food Systems and Community Economic Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 4–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, J.; Woods, T. Placing community supported agriculture in local food systems. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2024, 22, 2318936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssell, S.; Lankoski, L. The sustainability promise of alternative food networks: An examination through “alternative” characteristics. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.A.; Khanal, B.; Messer, K.D. Are consumers no longer willing to pay more for local foods? A field experiment. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2024, 53, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Malone, T. The role of collective food identity in local food demand. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2021, 50, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, M.; Fry, M. Growing local food movements: Farmers’ markets as nodes for products and community. Geogr. Bull. 2024, 56, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, W.; Pino, G. Do US citizens support government intervention in agriculture? Implications for the political economy of agricultural protection. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, U.; Kneafsey, M.; Kay, C.S.; Doernberg, A.; Zasada, I. Sustainability impact assessments of different urban short food supply chains: Examples from London, UK. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzembacher, D.E.; Meira, F.B. Sustainability as business strategy in community supported agriculture: Social, environmental and economic benefits for producers and consumers. Br. Food J. 2019, 21, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasmanaki, E.; Mangioros, V.; Fytopoulou, E.; Tsantopoulos, G. The practices of small and medium-sized agricultural businesses affecting sustainability and food security. J. Glob. Bus. Adv. 2020, 13, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.E.; Keane, C.R.; Burke, J.G. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health Place 2010, 16, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.; Bell, A.; Saherwala, A.; Lewis, S.; Rybarczyk, G.; Wetzel, R. Assessing the existence of food deserts, food swamps, and supermarket redlining in Saginaw: A small, racially segregated mid-Michigan city. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2025, 14, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byker, C.J.; Misyak, S.; Shanks, J.; Serrano, E.L. Do Farmers’ Markets Improve Diet of Participants Using Federal Nutrition Assistance Programs? A Literature Review. Available online: https://scholarworks.montana.edu/handle/1/9517 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Sadler, R.C.; Gilliland, J.A.; Arku, G. Community development and the influence of new food retail sources on the price and availability of nutritious food. J. Urban Aff. 2013, 35, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J. A farmers’ market in a food desert: Evaluating impacts on the price and availability of healthy food. Health Place 2009, 15, 1158–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislen, L.; Woods, T.; Meyer, L.; Routt, N. Grasshopers Distribution: Lessons Learned and Lasting Legacy; College of Agriculture, Food, and Environment, University of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agc/pubs/SR/SR108/SR108.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Kraeger, P.; Phillips, R.G.; Lubin, J.H.; Weir, J.; Patterson, K. Assessing Healthy Effects between Local Level Farmer’s Markets and Community-Supported Agriculture and Physical Well-Being at the State Level. Sustainability 2024, 16, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teig, E.; Amulya, J.; Bardwell, L.; Buchenau, M.; Marshall, J.A.; Litt, J.S. Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: Strengthening neighborhoods and health through community gardens. Health Place 2009, 15, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, K.H.; Stephenson, T.J.; Mayes, L.; Stephenson, L. Nutrition knowledge and dietary habits of farmers markets patrons. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 23, 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R.A.; Hamel, Z.; GiarroccoZ, K.; Baylor, R.; Mathews, L.G. Buying in: The influence of interactions at farmers’ markets. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, L.; Norris, K.; Kolodinsky, J.; Nelson, A. The role of social cognitive theory in farm-to-school-related activities: Implications for child nutrition. J. Sch. Health 2013, 83, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA 2022 Census of Agriculture Highlights—Female Producers. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Highlights/2024/Census22_HL_FemaleProducers.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Trauger, A.; Sachs, C.; Barbercheck, M.; Brasier, K.; Kiernan, N.E. “Our market is our community”: Women farmers and civic agriculture in Pennsylvania, USA. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.B. Preserving the Family Farm: Women, Communityy and the Foundations of Agribusiness in the Midwest, 1900–1940. By Mary Neth (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995, xiii) and Transforming Rural Life: Dairying Families and Agricultural Change, 1820–1885. By Sally McMurry (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. xii). J. Soc. Hist. 1996, 29, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, M.C. Potential challenges for beginning farmers and ranchers. Choices 2011, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Fremstad, A.; Paul, M. Opening the farm gate to women? The gender gap in US agriculture. J. Econ. Issues 2020, 54, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.; Valentina, H.; Denis, N. Entry and Exit from Farming: Insights from 5 Rounds of Agricultural Census Data. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Meeting, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 2–6 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, C.; Stephens, H.; Weinstein, A. Where are all the self-employed women? Push and pull factors influencing female labor market decisions. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, S.; Stengel, E. Working households: Challenges in balancing young children and the farm enterprise. Community Dev. 2020, 51, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Segovia, M.S.; Palma, M.A.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Rainey, R.L. Do Consumers Support Beginning and Female Farmers? J. Agric. Appl. Econ. Assoc. 2023, 2, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, J.; Njuki, E.; Griffin, T. Precision Agriculture in the Digital Era: Recent Adoption on U.S. Farms; Economic Information Bulletin No. 248; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavoss, M.; Capehart, T.; McBride, W.D.; Effland, A. Trends in Production Practices and Costs of the U.S. Corn Sector; Economic Research Report 294 (ERR-294); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=101721 (accessed on 25 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ruemenapp, M.A. America’s changing urban landscape: Positioning Extension for success. J. Hum. Sci. Ext. 2017, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’sullivan, C.A.; Bonnett, G.D.; McIntyre, C.L.; Hochman, Z.; Wasson, A.P. Strategies to improve the productivity, product diversity and profitability of urban agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2019, 174, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M.V. The Rise of Urban Agriculture: A Cautionary Tale-No Rules, Big Problems. Wm. Mary Bus. L. Rev. 2013, 4, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, T.; Dawodu, A.; Mangi, E.; Cheshmehzangi, A. Exploring current trends, gaps & challenges in sustainable food systems studies: The need of developing urban food systems frameworks for sustainable cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Hou, Y.; Lim, R.B.; Gaw, L.Y.; Richards, D.R.; Tan, H.T. Comparison of vegetable production, resource-use efficiency and environmental performance of high-technology and conventional farming systems for urban agriculture in the tropical city of Singapore. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feenstra, G.; Hardesty, S. Values-based supply chains as a strategy for supporting small and mid-scale producers in the United States. Agriculture 2016, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. Financial viability of an on-farm processing and retail enterprise: A case study of value-added agriculture in rural Kentucky (USA). Sustainability 2020, 12, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivarnik, L.F.; Richard, N.L.; Wright-Hirsch, D.; Becot, F.; Conner, D.; Parker, J. Small-and Medium-Scale New England Produce Growers’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Implementation of On-farm Food Safety Practices. Food Prot. Trends 2018, 38, 156–170. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption, a Proposed Rule; FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA): Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, L. Contested terrain: The ongoing struggles over food labels, standards and standards for labels. In Labelling the Economy: Qualities and Values in Contemporary Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ./Rev. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, R.A.; MacDonald, J.M.; Korb, P. Small Farms in the United States Persistence Under Pressure. In Economic Information Bulletin Number 63; Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, M.C.; Mohamad, A.A.; Chin, C.H.; Ramayah, T. The Impact of Natural Resources, Cultural Heritage, and Special Events on Tourism Destination Competitiveness: The Moderating Role of Community Support. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 3, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Bellia, C.; Giurdanella, C.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S. Digital influencers, food and tourism—A new model of open innovation for businesses in the Ho. Re. Ca. sector. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okrent, A.M.; Elitzak, H.; Park, T.; Rehkamp, S. Measuring the Value of the US Food System: Revisions to the Food Expenditure Series; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- USDA-ERS. Data Products, Ag and Food Statistics: Ag and Food Sectors and the Economy. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/ag-and-food-sectors-and-the-economy (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Valencia, V.; Wittman, H.; Blesh, J. Structuring markets for resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Power, B.; Bogard, J.R.; Remans, R.; Fritz, S.; Gerber, J.S.; Nelson, G.; See, L.; Waha, K.; et al. Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: A transdisciplinary analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e33–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany-McFadden, D. Horticulture, Organics and Small Farm Provisions in the Farm Bill. 2009. Available online: https://webdoc.agsci.colostate.edu/DARE/ARPR/ARPR%2009-01.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Coon, J.J.; Easley, M.J.; Williams, J.L.; Hambrick, G. Farmer perceptions of regenerative agriculture in the Corn Belt: Exploring motivations and barriers to adoption. Agric. Hum. Values 2025, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCanne, C.E.; Lundgren, J.G. Regenerative agriculture: Merging farming and natural resource conservation profitably. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Cramer, S. Transforming to a regenerative US agriculture: The role of policy, process, and education. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R.; Biklé, A.; Archuleta, R.; Brown, P.; Jordan, J. Soil health and nutrient density: Preliminary comparison of regenerative and conventional farming. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, A. An overview of global organic and regenerative agriculture movements. In Organic Food Systems: Meeting the Needs of Southern Africa; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2020; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.; Greene, C.; Skorbiansky, S.R.; Hitaj, C.; Ha, K.; Cavigelli, M.; Ferrier, P.; McBride, W. US Organic Production, Markets, Consumers, and Policy, 2000–2021. 2023. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/333551?v=pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Liu, X.; Ibrahim, M. Brand Name Effect of Organic Farming for Small-Scale Farms. 2015. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/230012?v=pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Manono, B.O.; Gichana, Z. Agriculture-Livestock-Forestry Nexus: Pathways to Enhanced Incomes, Soil Health, Food Security and Climate Change Mitigation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Earth 2025, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeycutt, C.W.; Morgan, C.L.; Elias, P.; Doane, M.; Mesko, J.; Myers, R.; Odom, L.; Moebius-Clune, B.; Nichols, R. Soil health: Model programs in the USA. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šūmane, S.; Miranda, D.O.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Czekaj, M.; Duckett, D.; Galli, F.; Grivins, M.; Noble, C.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Toma, I.; et al. Supporting the role of small farms in the European regional food systems: What role for the science-policy interface? Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallander, S.; Smith, D.; Bowman, M.; Claassen, R. Cover Crop Trends, Programs, and Practices in the United States; EIB-222; US Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deines, J.M.; Guan, K.; Lopez, B.; Zhou, Q.; White, C.S.; Wang, S.; Lobell, D.B. Recent cover crop adoption is associated with small maize and soybean yield losses in the United States. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.; Cowan, T. Farm Bill Primer: Support for Local Food Systems. Congressional Research Service Report No. IF11252. 2018. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF11252.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Hightower, L.S.; Brennan, M.A. Local Food Systems, Ethnic Entrepreneurs, and Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 Annual Meeting (No. 149696), Washington, DC, USA, 4–6 August 2013; Agricultural and Applied Economics Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, P.; Christenson, J.A. The Cooperative Extension Service: A National Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.K.; Kime, L.F. Programs to Encourage Small Farmers to Consider Entrepreneurial Options. Zesz. Nauk. Wyższej Szkoły Ekon.-Społecznej Ostrołęce 2016, 23, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.; Rocker, S.; Phillips, H.; Heins, B.; Smith, A.; Delate, K. The importance of social support and communities of practice: Farmer perceptions of the challenges and opportunities of integrated crop–livestock systems on organically managed farms in the northern US. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, C.; Eschbach, C.; Shelle, G. Addressing farm stress through extension mental health literacy programs. J. Agromedicine 2022, 27, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, E.L.; Liamputtong, P. Community gardening and health-related benefits for a rural Victorian town. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Farm Service Agency. Farm Service Agency Resources. Available online: https://www.fsa.usda.gov/resources (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Programs & Initiatives. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- USDA Rural Development. All Rural Development Programs. Available online: https://www.rd.usda.gov/programs-services/all-programs (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- USDA Food and Nutrition Service. FNS Nutrition Programs. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/programs (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Boys, K.A.; Fraser, A.M. Linking small fruit and vegetable farmers and institutional foodservice operations: Marketing challenges and considerations. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 34, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, J.D.; Hinrichs, C.C. Moving local food through conventional food system infrastructure: Value chain framework comparisons and insights. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Benjamin, T.; Guan, W.; Feng, Y. Food Safety Education Needs Assessment for Small-Scale Produce Growers Interested in Value-Added Food Production. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.commonmarket.coop/sustainability/farming-for-the-future/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Katchova, A.L.; Ahearn, M.C. Dynamics of farmland ownership and leasing: Implications for young and beginning farmers. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2016, 38, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.sare.org/grants/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Niewolny, K.L.; Lillard, P.T. Expanding the boundaries of beginning farmer training and program development: A review of contemporary initiatives to cultivate a new generation of American farmers. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2010, 1, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P. Is it time to take vertical indoor farming seriously? Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, I.; Borges, J.A.; Machado, J.A. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand the intention of small farmers in diversifying their agricultural production. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 49, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tool | Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Price Loss Coverage | Provides payments when the effective price for a covered commodity falls below its effective reference price | [179] |

| Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program | Offers financial support to producers of non-insurable crops to protect against natural disasters. Can cover specialty crops. | [179] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manono, B.O. Small-Scale Farming in the United States: Challenges and Pathways to Enhanced Productivity and Profitability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156752

Manono BO. Small-Scale Farming in the United States: Challenges and Pathways to Enhanced Productivity and Profitability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156752

Chicago/Turabian StyleManono, Bonface O. 2025. "Small-Scale Farming in the United States: Challenges and Pathways to Enhanced Productivity and Profitability" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156752

APA StyleManono, B. O. (2025). Small-Scale Farming in the United States: Challenges and Pathways to Enhanced Productivity and Profitability. Sustainability, 17(15), 6752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156752