Abstract

In an era where sustainable development is increasingly a core strategic issue for businesses, how top management, as the architects of corporate strategy, can achieve a synergy of economic, social, and environmental benefits through internal management mechanisms to promote corporate sustainability is a central focus for both academia and practice. This study aims to explore how Executive Cognitive Flexibility (CF) influences Firm Performance and to uncover the mediating effects of Non-market Strategy. We use panel data from Chinese A-share listed companies between 2016 and 2022 to examine and empirically analyze this mechanism. Our findings indicate that CF has a positive impact on Firm Performance. This relationship is realized through the pathway of Non-market Strategy, specifically manifesting as a reduction in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and an increase in Corporate Political Activity (CPA). Further analysis reveals that the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is differentially influenced by internal and external environmental contexts. The findings of this study provide important practical insights and policy recommendations for companies on cultivating executive cognitive flexibility, optimizing non-market strategies, and enhancing firm performance in various internal and external environments.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the integration of the global economy is accelerated, techno-logical innovation is accelerated, geopolitical and macroeconomic fluctuations are more intensive, and more grave sustainability concerns like global warming, resource deficiencies, and expanding social responsibility severely impact enterprise survival and sustainable development [1]. Although integration trends persist, anti-globalization views and growing trade tensions have resulted in the spectacular growth in world trade significantly decelerating. As per a UNCTAD report, global trade volume declined by approximately USD 1.5 trillion during 2023, falling 5% year-on-year. Amidst the external drags, enhancing and sustaining firm performance has become a core necessity for all organizations worldwide, including Chinese companies, to survive and thrive amidst turmoil. Company performance is not only a simple measure of a company’s health and management effectiveness but also critical to its adaptability, creativity, and competitiveness in a complex and dynamic environment. In-depth examination of company performance can allow companies to know their strengths and weaknesses precisely, optimize resource allocation and decision-making effectiveness, and thus formulate more promising and sustainable strategies to achieve long-term value creation and sustainable competitive advantages under a tougher competitive market and an uncertain external world. Therefore, enhancing company performance in a complicated and dynamic setting has become an unavoidable mission for scholars and practitioners.

In such a scenario, executive cognitive flexibility becomes increasingly vital, becoming a key requirement for firms to achieve greater performance under turbulent conditions. Cognitive flexibility, as a core cognitive style, refers to the executive’s ability to use diverse problem-solving strategies in a versatile way when encountering complex changes in the internal and external environment in order to effectively synthesize heterogeneous information, break through fixed cognition patterns, and dynamically adjust decision-making procedures [2]. This capacity compels businesses to quickly respond to trends in the marketplace, streamline internal operational effectiveness, and encourage ongoing innovation and expansion through impact on organizational culture and allocation of resources [3]. A timeless illustration is how, during the 1980s, General Electric’s legendary CEO, Jack Welch, precisely exemplified Upper Echelons Theory’s fundamental premise by utilizing his cognitive flexibility in the face of a rapidly developing market and internal inefficiency. It holds that corporate strategy and performance are significantly influenced by the CEO’s personal and cognitive styles. As a principal member of GE’s “upper echelon,” Welch’s unique “cognitive filter” allowed him to move beyond traditional thinking and intensely feel the new paradigm of globalization and efficiency supremacy. Based on high cognitive flexibility, he dropped the traditional “big and overarching” idea and introduced the “Be Number One or Number Two” business philosophy. He aggressively sold or closed over 200 money-losing businesses and rolled more than 40 business units into fewer than 20. All these restructuring actions were difficult decisions that Welch made based on his own cognition and values. These adaptive strategies, triggered by Welch’s cognitive flexibility, ultimately drove GE to radical restructuring and consistent growth. This supports the argument of Upper Echelons Theory: a top executive’s profound cognition influences the foundation for formulating adaptive strategies so that a company can attain consistent competitive advantage and growth in dynamic environments. However, existing literature is still lacking in an extensive and systematic examination of the inherent mechanisms through which executive cognitive flexibility acts, particularly on firm performance, particularly its dynamic impact channels in complex and unpredictable environments.

In the scenario of an increasingly complex and unstable global business landscape, traditional market rivalry is increasing, forcing companies to seek differentiated advantages and strategic resources through non-market channels [4]. This is the trend of business today. As pursuing economic benefits, non-market forces such as regulations and policies, social tendencies, popular opinion, and increasingly intense environmental problems are progressively supporting their power over corporate operational sustainability and long-term stability. Particularly in China’s unique socialist market economy system, its ever-improving legal and regulative environment, complex social ecology, and emphasis on ecological civilization construction and high-quality development make non-market forces profoundly affect corporate operations and performance. Executive cognitive flexibility here not only influences their keen insight into market opportunities but also has a considerable influence on their perception, interpretation, and response to non-market opportunities and challenges. More importantly, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Corporate Political Activity (CPA), being two of the key components of non-market strategy, largely rely upon the strategic ability and flexibility of executives in order to be effectively implemented. Executive cognitive flexibility enables them to more sensitively respond to potential environmental threats, social norms, and government opportunities in the non-market environment and nimbly change CSR investments and CPA strategies to better accommodate the specific needs of the Chinese market. This versatility not only creates new strategic space for enhancing the performance of companies but, above all, allows companies to build sustainable, environmentally friendly, socially responsible, and well-governed competitive powers, thereby propelling long-term sustainable value creation. Therefore, with non-market strategy as a key mediating variable between executive cognitive flexibility and firm performance, there can be a more comprehensive and detailed explication of the complex mechanisms through which executive cognitive flexibility influences enterprise sustainable development, giving birth to richer theoretical implications and practical recommendations on grasping the determinants of firm performance in China.

Despite existing research having focused on the impact of executives on firm performance, it has primarily concentrated on entrepreneurial identity [5], executive heterogeneity [6], and executive compensation [7] on firm performance. Furthermore, only a small number of studies have examined the impact of executive cognition on firm performance [8], but these have been conducted in static environments, lacking an exploration of the mechanisms through which executive cognition, particularly executive cognitive flexibility, influences firm performance in dynamic environments.

In brief, to address the research gap on the mechanisms by which executive cognitive flexibility influences firm performance, this paper, using data of Chinese A-share listed firms for 2016–2022, develops an executive cognitive flexibility index via text analysis and tests its effect on firm performance empirically. Meanwhile, under the “cognition–behavior–performance” paradigm, non-market strategy is proposed as a mediating variable. The paper proves that executive cognitive flexibility has a positive effect on firm performance, and non-market strategy mediates between them. Particularly, executive cognitive flexibility improves firm performance by decreasing the taking of social responsibility and escalating corporate political activity.

In comparison to current literature, the research findings of this paper can be primarily illustrated as below: Firstly, there is limited current research on executive cognitive flexibility. Based on an empirical study, the paper identifies that executive cognitive flexibility has a positive impact on business performance, and, at the same time, non-market strategy would take an intermediary variable, namely, operating under the mechanism of two modes: corporate social responsibility and political activity. Secondly, there is an imperative guide value for the management practice of corporations. This study stresses that there is great significance for executive cognitive flexibility development, which could help executives achieve an integrated and future-visionary vision of the market, as well as the non-market environment, making corporations grasp strategic opportunities. Meanwhile, there is an introduction and explanation of non-market strategic channels, which have an advantage for corporations to explore and capitalize benefits of non-market opportunities, achieving differentiation advantages based on building a non-market strategic system for core business.

The research paper is as below: The literature of executive cognitive flexibility and firm performance is elaborated, and defects of the theory of existing research are mentioned in the second part, based on upper echelon theory and stakeholder theory, etc. In the third part, based on existing research, a research framework is established based on upper echelon theory and stakeholder theory, etc. Executive cognitive flexibility impacts on firm performance are elaborated, and the mechanistic channels of non-market strategies, i.e., the above-mentioned two channels of corporate social responsibility and corporate political activities, are examined. The research approach of sample selection and variable measurement is elaborated in the fourth part. Empirical results analysis of descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, multiple linear regression analysis, robust checking, and heterogeneity analysis of sample data is provided in the fifth part. Directions for future research and recommendations for companies to strengthen executive cognitive flexibility to promote development are provided in the abstract of the sixth part of the paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Executive Cognitive Flexibility

Cognition, the very root of psychological study, is the mental functioning and perceptual capacity by which human individuals receive, process, and interpret stimulation from the external world, including perception, memory, reasoning, and language. For management, March and Simon [9] initially elaborated upon the theory of cognition, where they assumed that managers’ choices of behavior or design of strategy of day-to-day functioning are founded on cognitive assumptions of their own. Such cognitive assumptions include the manager’s fundamental assumptions about what is ahead, management’s perception and interpretation of alternative options, and overall assessment of consequences that could potentially follow for each alternative.

As a core component of executive function, cognitive flexibility implies, on the one hand, the ability to sense and decipher messages of the environment, and on the other hand, to perform and modify strategies in reply [10]. Those having superior cognitive flexibility are able to cleverly modify their behavior under dynamic rules and conditions, come up with alternative solutions to problems, and select the most appropriate sequence of events for the circumstances. On that basis, Cui et al. [11] posit that cognitive flexibility involves the two most salient dimensions. The first is cognitive switching, which involves the perception of change of the external environment, reconsideration of problems under new conditions, provision of diverse interpretations, and rapid switching of point of view for new adaptive responses. The other is strategic fit, which involves having access to a knowledge store to select and utilize the most adaptive and appropriate strategies and plans for different situations. Therefore, cognitive flexibility enables consideration of ideas from different perspectives and facilitates their thinking and performance to remain sensitive to environment- and task-related ambiguity. People with high cognitive flexibility are less prone to cognitive fixation but, instead, unwittingly have a tendency to seek new information as a means of redirecting their attention to produce fresher responses according to situational contingencies [12]. On that literature basis, executive cognitive flexibility is characterized as the ability of high-level managers to perceive and accommodate environmental change by varying their cognitive structures, behavioral responses, and strategic choices flexibly to meet changing situational demands.

Existing research on the measurement of executive cognitive flexibility has primarily focused on primary data, mainly through surveys and experiments. Firstly, studies often use survey scales; for instance, Kiss et al. [13] measured executive cognitive flexibility using 12 items from a cognitive flexibility scale. Secondly, some scholars have also adopted experimental methods to measure executive cognitive flexibility. Peterson et al. [14] stimulated participants with both images and text to investigate their cognitive style preferences. However, primary data measurement methods have several shortcomings. While survey scales can directly reflect an individual’s self-perception, they are susceptible to cognitive biases and struggle to capture dynamic changes in real-world situations. Experimental research, though capable of exploring causal relationships, is limited by artificially simulated environments, which restricts the external validity and situational generalizability of the results, and is typically constrained by smaller sample sizes. Due to these limitations of primary data measurement, employing secondary data to measure executive cognitive flexibility can handle larger and longer-span samples, enhancing the universality and robustness of the research, and more authentically reflecting executives’ cognitive characteristics and dynamic changes in actual operations. In terms of secondary data measurement, it mainly involves extracting keywords from corporate annual reports to gauge managerial cognition [15].

2.2. The Influence of Executive Cognition on Firm Outcomes

Executive cognition, according to upper echelon theory, is generally known as a primary antecedent of business strategic choice and eventually firm performance [16]. Firstly, from the view of science, there has been comparatively wide discussion on executive cognition’s effect on firms under static environments. For instance, Schwenk [17] employed behavioral decision theory in testifying to the effect of executive cognitive bias on corporate policy; Amason and Sapienza [18] believed executive cognitive conflict affects corporate strategy making; Tallon [19] also investigated executive cognition and executive cognition’s association with firm growth by examining the opinions of information technology among 133 executives; and Devine et al. [20] studied executive cognition’s effect on firm performance under the backdrop of culture. However, under dynamic environments, study is not the norm, and is mostly represented by executive risk cognition analysis [21]. This also reflects that current studies are mostly still on the effect of executive cognition on firms under static environments, and without a comprehensive study on multilayered executive cognition under dynamic environments. Times today are filled with high global economic uncertainty, iterative technology, and emerging market competition. Firms’ issues are no longer individual, predictable situations, but also uncertain, vague, and complicated dynamic situations. Executive cognition under dynamic environments is, therefore, of specific urgency and necessity to be studied. Executive cognitive flexibility is indeed an executive cognitive attribute widely applied to dynamic environments, which is of utmost importance to be comprehensively studied. Executive cognitive flexibility is needed in dynamic environments so that executives are empowered with the added authority of flexibility, foresight, and quickness of updating cognition. How their cognitive characteristics mold corporations’ strategic adjustment, re-allocation of resources, and final performance under sustained change is central to explaining corporate long-perduring resilience, as well as long-run competitiveness. Neglecting dynamic factors can cause an incomplete explanation of the executive cognition role and draw boundaries of the guiding value of effects utilized.

Secondly, in mechanism analysis, research has largely unfolded from the perspective of market factors. This is primarily reflected in the path mechanisms of competitive dynamics [22], market demand [23], market pricing [24], and supply chain [25]. From the perspective of non-market factors, executive cognition’s impact on firms is reflected at the ESG level [26,27], but these studies often remain at a superficial examination of non-market factors’ influence, failing to deeply analyze how executive cognition influences firm performance through specific non-market strategic actions. Due to this, existing research is still insufficient in exploring the deeper mechanism of how executive cognitive flexibility drives firms to adopt specific non-market strategic actions, thereby affecting firm performance. In-depth research in this area can not only fill theoretical gaps but also provide a crucial theoretical basis and practical guidance for enterprises to formulate more forward-looking and adaptive strategies in a complex and volatile global business environment.

From the above literature review, even though executive cognition has attracted broad attention with its own influences on firm performance, there exist the following research gaps for future study: Firstly, for the measurement of executive cognitive flexibility, existing research has mainly depended on primary data, suffering from the issue of small sample bias. Hence, there is the absence of objective, large-sample, and dynamic measurements for such an important executive personality. Secondly, upon executive cognition’s influence upon firms, existing literature has mainly depended on static analysis of the environment without a large-scale study of executive cognition (specifically executive cognitive flexibility) as to its influences upon firm performance under dynamic environments. Thirdly, upon analysis of the mechanism of executive cognition’s influences upon firm performance, existing research has mainly depended on the market-factor view with comparatively much less attention upon non-market forces. Even such studies involving non-market forces remain surface-oriented in nature of influences, without exploring deeply as to executive cognition’s influences upon firm performance based upon discrete non-market strategic behaviors.

In summary, this paper employs a text analysis method to measure executive cognitive flexibility and, under the “cognition–behavior–performance” logical framework, analyzes the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance and the mediating role of non-market strategy in this pathway.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Executive Cognitive Flexibility and Firm Performance

Upper echelons theory posits that organizational strategy execution within a firm reflects the unique values and cognitive bases of a firm’s senior managers directly [28]. With internal and external environments faced by firms growing more turbulent and intricate—such as mounting concerns and issues on sustainability—senior managers are plagued by bounded rationality. This means that they simply cannot absorb all available internal and external information. Instead, they are guided by selective interpretations of the environment, an interpretive capacity that reaches comprehension of economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Such readings themselves are strongly informed by their own histories, experiences, and psychological dispositions, which in turn exert a major impact on firm performance. Here, cognitive flexibility can be seen as a key managerial way of thinking, which can be expressed in the sensitivity and responsiveness of managers to the external world (either market, social, or environmental). Specifically, executive cognitive flexibility is the process through which a management team can change their style of thinking and method of making decisions by alternating between two modes of cognition in response to the demands of a decision-making task when faced with a dynamic and complex situation [29]. The gimmick is for executives to recognize the existence of multiple alternatives in a situation and be prepared to adapt accordingly. This adaptability enables decision-makers to quickly react to change within the external environment, with resulting decisions enabling corporate profitability.

Executive cognitive flexibility’s impact on firm performance can be explained by two main behavioral mechanisms. First, managers with greater cognitive flexibility are better at proactively sensing and capturing market opportunities [30]. Their ability to process dynamic and intricate information enables them to recognize valuable cues that underpin strategic redirection. As market circumstances shift, they can rapidly change strategic priorities to take advantage of emerging opportunities, which manifests as a more responsive allocation of capital, technology, and human resources to the most favorable business initiatives, thus improving the return on investment. A traditional example is the case of Netflix, where the cognitive flexibility of its executives greatly enhanced the firm’s performance. Early in the 21st century, faced with the emergence of internet streaming, Netflix executives, leveraging their high level of cognitive flexibility, acutely sensed this market opportunity. They did not hold on to their conventional DVD rental business but rather exhibited the capacity to flexibly revise their mindset and strategy. They aggressively shifted from physical rentals to internet streaming services and incessantly invested in original content. This ability to rapidly sense, adapt, integrate information, and redistribute resources during environmental shifts allowed Netflix to effectively capture market initiative, eventually growing into a global streaming giant and drastically improving its firm performance.

Second, cognitively flexible executives are also more effective at rapidly identifying environmental threats and internal organizational problems, facilitating timely corrective actions [31]. Acting as a “cognitive radar,” this flexibility enables decision-makers to effectively integrate disparate information from both the external environment (scanning for opportunities) and internal systems (monitoring for weaknesses). This dual focus allows the firm to preemptively mitigate potential risks and maintain its adaptive capacity and competitive advantage [32], ultimately fostering performance growth. In summary, by enhancing a firm’s adaptability to external change, promoting the capitalization of market opportunities, and enabling the avoidance of potential risks, executive cognitive flexibility serves as a positive driver of firm performance. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Executive cognitive flexibility is positively correlated with firm performance.

3.2. The Mediating Role of Non-Market Strategies

In the complicated and dynamic business world of today, firm performance is not only achieved by conventional market competition strategies; non-market influences and, thus, derived non-market strategies also have an important role to play. Non-market strategies refer to the methods that firms take to deal with non-market environmental problems—such as political, social, legal, technological, and cultural problems—through interactions with the government and media, among other organizations. Non-market strategies can provide favorable external circumstances for firms, thus obtaining a competitive advantage and improving performance. As stated by the resource-based view [33], the limited nature of a firm’s resources makes their allocation in strategic action paramount. Since senior managers are the final decision-makers regarding the allocation of corporate resources, their cognitive flexibility has a direct bearing on how they perceive, evaluate, and strategically allocate resources. Managers with greater cognitive flexibility are not only able to astutely grasp market trends but also go beyond the extent of conventional market competition, looking into and analyzing potential opportunities and threats within the non-market environment in a holistic manner. Cognitively flexible executives are better able to recognize that a firm’s long-term competitive advantage does not only originate from effectively marshaling market resources, but also from gaining and leveraging scarce, valuable, and inimitable non-market resources through non-market channels. Consequently, these executives will, guided by their astute observation and strategic judgment of the external environment, more effectively and timely allocate resources between market and non-market strategies to enhance firm performance. Such a holistic resource allocation strategy helps firms possess distinctive advantages that market strategies cannot easily imitate. Corporate non-market strategies generally cover two main areas: corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate political activity. Among them, CSR means those strategies taken by companies beyond economic and legal requirements, beginning with the stakeholder approach, by establishing good relationships and fulfilling their expectations of corporate conduct [34]. Corporate political activity means those actions taken by companies to affect government policies, regulations, or decisions in a manner beneficial to their own operations and growth. Essentially, executives’ cognitive flexibility helps them to thoroughly sense the non-market context and, according to that perception, strategically deploy limited resources, thus indirectly contributing to firm performance.

3.2.1. The Mediating Path of Corporate Social Responsibility

Pfeffer [35] suggests that an individual’s behavioral motivation stems from their attitudes and cognitions toward things. Thus, corporate social responsibility behaviors are ultimately influenced by top managers’ cognitions. In the context of the separation of ownership and control, executives may tend to overly focus on short-term profits, potentially sacrificing the long-term interests of shareholders and other stakeholders to prioritize company resources for achieving their own short-term goals [36]. This short-sighted tendency often leads firms to allocate resources to market strategies that can generate direct benefits in the short term, thereby reducing their assumption of social responsibility [37].

From the stakeholder theory perspective, firms, while pursuing their own development, must manage and balance the needs and expectations of various groups of stakeholders. Not only does this relate to a firm’s legitimacy and reputation, but it also directly influences its ability to acquire and preserve essential resources. When there is a lack of resources and stress from managers for immediate outcomes, managers’ cognitive flexibility is imperative. It enables chief executives to make a more rational and enlightened cost–benefit assessment [38], evaluating the real impact of various CSR investments on varied stakeholders (for example, shareholders, staff, buyers, communities) and contrasting their long-term value potential with immediate benefits. Cognitively flexible chief executives can quickly notice and react to changes in the outer environment, adjusting their resource strategy accordingly. For executives who are more cognitively flexible, they can better distinguish CSR activities of low salience to the main firm strategy or with short-run potential for substantial overall benefit. These can be thought of as having the potential to engender resource dispersal or even harmful influence on overall operational efficiency in the short term, especially under conditions of resource restraint [39]. Thereby, in the context of resource constraints and legitimate concern for short-term performance, cognitive flexibility at an executive level allows managers to perform cost–benefit analysis better. Such leads to a strategic CSR investment framework alignment in directing resources to places that yield more tangible and measurable overall benefits. This restructuring of resources does not occur in the short term, but rather it is evidence of flexible revision of executives’ way of thinking and decision-making style, demonstrating their effective strategic allocation of limited resources under the complex environment. This allows the company to effectively cope with short-term troubles yet continue to maintain core competitiveness when building long-term sustainable development.

By pruning selectively investments in seemingly “cost-center” social responsibility initiatives, businesses can free up more valuable capital and invest it in production and operations with more concrete and measurable short-term returns. As an example, in its early years, Tesla allocated scant capital to traditional advertising and certain social responsibility initiatives but invested money in electric vehicle R&D, battery technology, and Gigafactory construction. These concentrated investments of resources can enormously increase the efficiency of a firm’s operations, kill wasteful expenditures, and enhance core business orientation in the short term. This profitable redeployment and careful skidding of resources were primary reasons for the firm’s better bottom-line performance, which enabled it to achieve profitability goals earlier in the very competitive market situation.

3.2.2. The Mediating Path of Corporate Political Activity

Corporate political activity, as one of the significant non-market actions, is regarded as a resource-seeking behavior [40]. It is supposed to help companies deal with complex external environments by searching, acquiring, and using scarce resources effectively and thereby removing inherent bottlenecks, as well as gaining competitive advantages. Resources companies invest in political activities have strong connections with top managers’ perceptions [41]. Institutional theory, from an institutional theory point of view, is all about organizational response, adaptation to, and change of their institutional context in a bid to gain legitimacy and vital resources. Institutional theory, in particular, contends that organizational action does not rest exclusively on rational choice or efficiency but is largely influenced by the social, political, and cultural norms, rules, and beliefs embedded in its environment. To survive and develop, organizations must conform to the legitimate expectations of the external environment and buffer these institutional pressures by experiencing isomorphic changes, such as mimicking successful organizational forms or practices. However, executive cognitive capacity, and, more particularly, cognitive flexibility, enables not only the passive acceptance and learning from the institutional environment but also the active sensing and exploitation of gaps or opportunities in the institutional web. They are even capable of shaping and reshaping institutional rules through being politically involved so as to achieve a desired competitive stake. In such a system, managers who have greater cognitive flexibility demonstrate high performance in bargaining and strategic use of such complex institutional environments. Managers who have high cognitive flexibility can sense acutely and investigate intensively subtle shifts in the political environment, identify at once budding trends in policies, regulations, and power structures, and, thus, reveal latent institutional threats or opportunities. This cognitively flexible approach allows managers to think multidimensionally in the face of high uncertainty, foresee the potential impact of different political strategies, and determine the optimal timing of the most appropriate political actions. For instance, they are able to recognize industry threats or opportunities caused by specific policy changes and construct political coalitions ahead of time to coincide with strategic changes. Through this type of strategic, proactive political action, managers are able to get ahead of competitive resource wars and power struggles and, in doing so, secure more policy support, scarce resources, and strategic partnership possibilities for their firms.

In a competitive and uncertain environment, firms can establish good relationships with external stakeholders such as government departments and industry associations through effective political activity, securing crucial resources, including policy support, financial subsidies, tax incentives, market access, and strategic cooperation. This directly or indirectly enhances the firm’s revenue and profitability. Existing research shows that firms with stronger political activity support can receive more positive media coverage, which not only helps enhance their public image but also creates more opportunities for resource acquisition [42]. Furthermore, active political activity can also promote breakthroughs in corporate innovation, for example, by securing government R&D funding and participating in industry standard setting, thereby helping firms gain a competitive advantage in technology R&D and market expansion. Tsai [43] points out that firms with strong political activity can leverage resource allocation advantages to accelerate innovation processes, thereby significantly enhancing their market competitiveness and profitability. Therefore, cognitive flexibility, by improving managers’ political sensitivity and adaptability, promotes the more effective use of political activity by firms to acquire resources, reduce risks, and enhance their market position. Through the effective use of political activity, firms can create more opportunities in a complex economic environment, thereby promoting the improvement of their financial performance.

Based on this, we propose:

H2.

Non-market strategies mediate the relationship between cognitive flexibility and firm performance.

H2a.

Corporate social responsibility mediates the relationship between cognitive flexibility and firm performance.

H2b.

Corporate political activity mediates the relationship between cognitive flexibility and firm performance.

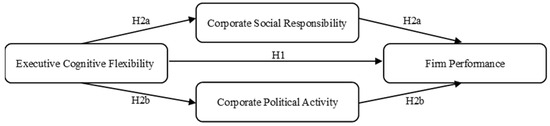

In summary, there is a conceptual model of “Executive Cognitive Flexibility–Non-Market Strategies–Firm Performance,” as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model diagram.

4. Research Design

4.1. Data Sources and Sample Selection

This paper uses a panel dataset of Chinese A-share listed firms between 2016 and 2022 to test our hypotheses empirically. Data for our major variables were collected from a number of authoritative databases. Data for the construction of the executive cognitive flexibility index were retrieved from the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section of firm annual reports, which were collected from the WIND database, the official websites of the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, and Juchao Information Network (www.cninfo.com.cn). Data on corporate social responsibility (CSR) were collected from the dedicated CSR module in the CSMAR database. Data for corporate political activity and all the other firm-level financial and governance variables were also collected from the CSMAR database.

To construct the final sample, we applied the following screening criteria:

- (1)

- Exclusion of Financial and Public Utility Firms: We removed companies from the financial and public utility sectors. These sectors operate under unique business models, distinct accounting standards, and highly specific regulatory environments. Their differing competitive dynamics and governance structures could potentially obscure the true relationship between executive cognition, non-market strategies, and firm performance.

- (2)

- Exclusion of ST and *ST Designated Firms: We excluded firms that were labeled as ST (Special Treatment) or *ST (Particular Transfer), i.e., under the threat of being delisted. The purpose of this exclusion was to rid our analysis of the confounding effects of severe financial distress.

- (3)

- Exclusion of Firms with Significant Missing Data: Any observations with missing values for executive cognitive flexibility, firm performance, non-market strategies (CSR and CPA), or any control variables were excluded from the analysis. This ensures the robustness of our results across all observed variables.

Despite these necessary sample exclusions, our final dataset comprises 13,586 unbalanced panel data samples, which is still broad and broadly representative. By removing some industries like finance and public utilities, the remaining sample still covers a broad distribution of Chinese A-share listed companies over various core sectors, including manufacturing, information technology, real estate, and wholesale and retail. This broad coverage ensures that our research results represent typical patterns found in the majority of companies. The large sample size in this way leaves us with sufficient statistical power for this study to easily identify significant relationships among variables.

4.2. Model Specification and Variable Definition

To test our hypotheses, we follow the causal steps approach and specify a series of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models with industry and year fixed effects.

First, to test the direct effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance (H1), we estimate the following model:

TobinQi,t = α0 + α1CFi,t + α2∑Controli,t + Year + Ind + εi,t

In Model (1), TobinQ represents firm performance, CF represents executive cognitive flexibility, Control represents the selected control variables, Year represents year fixed effects, and Ind represents industry fixed effects. Through OLS regression of Model (1), the primary focus is on the coefficient α1.

Next, to test the mediating role of non-market strategies (H2a and H2b), we construct the following models:

CSRi,t = β0 + β1CFi,t + β2∑Controli,t + Year + Ind + εi,t

CPA i,t = β3 + β4CFi,t + β5∑Controli,t + Year + Ind + εi,t

TobinQi,t = γ0 + γ1CFi,t + γ2CSRi,t + γ3∑Controli,t + Year + Ind + εi,t

TobinQi,t = γ4 + γ5 CFi,t + γ6CPA i,t + γ7∑Controli,t + Year + Ind + εi,t

These models define CSR as corporate social responsibility and CPB as corporate political behavior; all other variables remain consistent with Model (1). Using OLS regression, Model (2) primarily focuses on coefficient β1, while Model (3) centers on coefficient β4. For Model (4), we examine coefficients γ1 and γ2, and for Model (5), we look at coefficients γ5 and γ6. Models (2) and (4) are designed to verify the mediating role of corporate social responsibility, whereas Models (3) and (5) aim to verify the mediating effect of corporate political behavior. Specifically, if β1, γ1, and γ2 are all significant in Models (2) and (4), this indicates that CSR acts as a mechanism through which executive cognitive flexibility enhances firm performance, though it may not be the sole mechanism. The same logic applies to the mediating effect of CPB in Models (3) and (5).

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

Firm Performance (Tobin’s Q): Tobin’s Q is defined as the ratio of a company’s stock market value to the replacement cost of its capital. It is more than just an indicator that measures a firm’s current asset value and its ability to generate sufficient returns from new investments. More importantly, it can transcend short-term accounting data to comprehensively capture the market’s holistic expectations and assessment of a firm’s future growth potential, innovation capabilities, brand reputation, and unique intangible assets. This includes, for instance, government relations and social capital accumulated through its non-market strategies [44].

4.2.2. Independent Variable

Executive Cognitive Flexibility (CF): Following the research of Deng [15], textual analysis is conducted on the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section of listed companies’ annual reports. The MD&A describes the company’s operating performance during the reporting period and its outlook for future development, directly or indirectly reflecting the direction and focus of managers’ attention. Since cognitive flexibility is the ability of managers to capture changes in the external environment and promptly adjust cognitive strategies, it is reflected by capturing keywords related to the perception of the external environment. Python 3.11 is used to count the frequency of keywords related to external environment perception, and this count is divided by the total number of characters in the annual report text (in thousands of characters). To ensure consistent dimensionality, the resulting ratio is multiplied by 100.

4.2.3. Mediating Variables: Non-Market Strategies

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Following Hu and Li [45], we measure the quality and credibility of CSR reporting, rather than just its existence. CSR is an index calculated as the average of two binary indicators: (1) a value of 1 if the firm’s CSR report has been independently audited by a third party, and 0 otherwise; and (2) a value of 1 if the report explicitly references the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, and 0 otherwise. This measure captures the firm’s commitment to standardized and verifiable CSR practices.

Corporate Political Activity (CPA): In China’s distinctive market environment, a company’s ability to forge and maintain strong ties with the government is paramount for its survival and growth. These connections often become crucial conduits for acquiring vital resources. Charitable donations, in this context, transcend mere fulfillment of social responsibility; they are a strategic non-market investment. Their purpose is to cultivate positive interactions with the government, thereby securing essential resources and competitive advantages for the enterprise [46]. Consequently, this study quantifies corporate political behavior by using the ratio of charitable donations to total assets, a methodology adopted from Cheng and Geng [47]. To ensure consistent dimensionality, the resulting ratio is multiplied by 1000.

4.2.4. Control Variables

This paper introduces six control variables: Asset Growth, Gross Profit, Liquid Ratio, TOP1 (shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder), Der (debt-to-equity ratio), and Board (executive team size).

All models include Year and Industry fixed effects to account for unobserved factors that vary over time and across industries.

The main variables and their definitions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definitions.

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the key variables. For executive cognitive flexibility, the values range from 0.000 to 1.030, with a mean of 0.240 and a standard deviation of 0.070, indicating a notable degree of variation across the sample firms. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) exhibits even greater dispersion, with a range of 0 to 2 and a standard deviation of 0.345. This suggests significant heterogeneity in the level of social responsibility engagement among firms. The range of values for corporate political behavior is between 0.000 and 16.090, indicating a certain gap in corporate political actions.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 presents the variable correlation coefficient matrix. The results show that all correlation coefficients between variables in the matrix are less than 0.7. Simultaneously, TobinQ is significantly positively correlated with executive cognitive flexibility (CF) and corporate political activity (CPA), and significantly negatively correlated with corporate social responsibility (CSR). Executive cognitive flexibility (CF) is significantly negatively correlated with corporate social responsibility (CSR) and significantly positively correlated with corporate political activity (CPA). These results are consistent with our expectations.

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis.

5.2. Baseline Regression

Table 4 shows the findings of the OLS regression analysis examining the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance. We report the findings stepwise to illustrate the stability of our results.

Table 4.

Benchmark regression results.

Column (1) presents a parsimonious specification featuring just our independent variable, executive cognitive flexibility (CF), but no control variables. The coefficient for CF is positive and statistically significant (α = 1.0357, p < 0.01), offering initial support for a positive link between executive cognitive flexibility and firm performance.

Column (2) reports the results for our complete specification as outlined in Model (1), with the complete set of control variables and year and industry fixed effects. The coefficient on executive cognitive flexibility (CF) is still positive and highly significant (α1 = 0.8486, p < 0.01). This offers strong empirical confirmation of Hypothesis 1 in that executives with higher cognitive flexibility are indeed linked to better firm performance.

This implies that executive cognitive flexibility not only indicates managers’ profound awareness of the external environment’s complexity and uncertainty but also their capacity for effective decision-making, strategy adjustment, and resource allocation optimization in the face of changing circumstances. In dynamic environments, executives with cognitive flexibility have the capacity to promptly detect and respond to external changes, flexibly combine information and insights from different sources, and then make decisions that favor the company’s growth and firm performance.

The findings for our control variables are generally in line with previous literature. Both Gross Profit and Liquidity Ratio are positively and significantly related to firm performance, which supports the expectation that greater profitability and higher short-term solvency lead to better firm valuation. In contrast, Ownership Concentration (TOP1) and Board Size are negatively and significantly related to firm performance. The negative coefficient on TOP1 is possibly due to the entrenchment effect, in that a dominant, largest shareholder might make decisions that benefit private interests at the cost of firm value. The negative impact of board size supports theories of group dynamics, which argue that larger boards tend to have slower decision-making processes, coordination problems, and diffusion of responsibility, all of which are harmful to firm performance.

5.3. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

To accommodate consideration of establishing baseline validity of estimates, as for criticism of endogeneity, various robustness checks were executed. Table 4 presents the findings.

(1) Addressing Endogeneity with Instrumental Variables (IV)

One of our main endogeneity issues is reverse causality, for which good-performing companies have resources to spare for hiring or building more cognitively flexible executives. To account for that, we use an IV 2SLS (two-stage least squares) regression. As the classical method used in the literature of strategic management and corporate finance, such as that of Dong et al. [48], including us, we use the one-period lag of the independent variable (CFt−1) of an instrument of the current executive cognitive flexibility (CFt). It is worth using a lag of a variable as an instrument because, by definition, they are correlated with their own current value (relevance) but have smaller chances of being correlated with the error term of the current period (exclusion restriction) because historical cognitive flexibility is impossible to be driven by future performance shocks.

Column (1) of Table 5 reports the 2SLS regression. Our first-stage results affirm the validity of the instrument. While the null hypothesis of underidentification of the model is rejected by the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM underidentification statistic of 0.000 (p = 0.000), its corresponding F-statistic, 194.07, is strongly bigger than the Stock-Yogo critical value for 10% maximal IV size, suggesting that our instrument is far, very far indeed, from being weak. In the second stage, the instrumented executive cognitive flexibility remains positive and significant. This means that even adjusting for its possible endogeneity, its positive effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance still persists, and as such, makes us even convinced of Hypothesis 1.

Table 5.

Robustness test results.

(2) Heckman Test

To address potential sample selection bias in the testing of the effect of executive cognitive flexibility on the performance of firms, we use the Heckman two-stage model. We estimate the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) in the first stage in a Probit model. In the second stage, we incorporate the IMR as a control variable into the conventional regression equation, which we use in the testing of the effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance. By incorporating the IMR into the model, we can remove potential selective bias that can hamper our research results. Regression outcome with the incorporation of the IMR is presented in Table 5, column (2). We notice that the regression coefficient of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance continues to be significantly positive, as is the situation without correcting for selection bias. This provides stronger assurance for the validity of our study results.

(3) Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

To overcome possible endogeneity due to self-selection bias, we adapted the method of Propensity Score Matching (PSM). For that, our sample is split into the group of high executive cognitive flexibility (the treatment group) and the group of low executive cognitive flexibility (the control group) along the executive cognitive flexibility median line. Then, propensity scores have been estimated based on Asset Growth, Gross Profit, Li-uid, TOP1, Der, and Board as controls and did 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching. Column (3) of Table 5 reports regression outcomes on the matched sample, where the regression coefficient of executive cognitive flexibility is still astonishingly positive at 1%, as is also for the regression results of the present study.

(4) Alternative Measure of the Dependent Variable

To ensure that our findings are not being pulled by a single measure of firm performance, we also conduct a robustness check based on an alternative measure. Instead of Tobin’s Q, based on market measures, which is an accounting-based measure commonly used, we employ Return on Assets (ROA) as an alternative accounting-based measure. Whereas Tobin’s Q reflects market perceptions, as well as future prospects, ROA reflects the firm’s historical operational efficiency of generating profit out of its asset base. By re-estimating our baseline model where ROA is being viewed as the dependent variable, we can study the generalizability of our findings. As can be seen from Column (4) of Table 5, the executive cognitive flexibility variable still has a positive and significant impact, and our main finding is also robust across different measures of performance.

(5) Controlling for Industry-by-Year Fixed Effects

Our baseline regression includes separate fixed effects for industries and for each year. To take into consideration potentially relevant, but otherwise unknown, time-varying shocks that might have extremely different effects across industries, however, an even stronger fixed-effects definition is used. We exclude the separate fixed effects for industries and for each year and include fixed effects for interactions of industries by years. This technique accounts for whatever otherwise unidentified heterogeneity is shared across all those firms belonging to each given pair of industry and year. Column (5), Table 5 reports results that show that the executive cognitive flexibility is still significant and unchanged, thereby affirming the robustness of our main result.

(6) Using a Lagged Dependent Variable

It is plausible that the effects of executive cognition on firm performance are not instantaneous and may manifest over time. To account for this possibility and to mitigate concerns about dynamic endogeneity, we re-estimate our model with the dependent variable (Tobin’s Q) lagged by one period. As reported in Column (6) of Table 5, the positive and significant association between executive cognitive flexibility and future firm performance persists. This result not only demonstrates the robustness of our findings but also suggests that the influence of executive cognition on performance is enduring.

5.4. Mechanism Test

We now test the mediating roles of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate political activity (CPA) in the relationship between executive cognitive flexibility and firm performance. The results are presented in Table 5.

5.4.1. The Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Table 6, columns (1) and (3), reveals that in Model (2), executive cognitive flexibility significantly reduces the undertaking of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (β1 = −0.4993, p < 0.01). This finding likely stems from the current Chinese context, where CSR requirements are often ambiguous, and ESG information disclosure is largely encouraged rather than mandated. Faced with limited resources and a volatile external environment, cognitively flexible executives, upon recognizing the importance of short-term financial returns, strategically choose to reduce the adoption of non-mandatory CSR initiatives. This allows them to reallocate finite resources toward core business activities that yield quicker economic benefits. In Model (4), cognitive flexibility remains significantly positively related to firm performance (γ1 = 0.7715, p < 0.01), while interestingly, CSR is significantly negatively related to firm performance (γ2 = −0.1543, p < 0.01). This combination of results further supports Hypothesis 2a. It indicates that executives, through their cognitive flexibility, influence the “behavioral” choice regarding CSR, which ultimately leads to an improvement in firm performance. This robustly validates the proposed “cognition–behavior–performance” logical chain.

Table 6.

Results of mediated effects test.

5.4.2. The Mediating Role of Corporate Political Activity (CPA)

Table 6, columns (2) and (4), reveals that in Model (3), executive cognitive flexibility significantly enhances the implementation of corporate political behavior (CPB) (β4 = 0.2316, p < 0.01). This suggests that when cognitively flexible executives “perceive” the bottlenecks arising from a rapidly changing external environment and the necessity of resource acquisition, their “behavior” involves actively identifying and leveraging various social resources. These resources include interpersonal networks, industry alliances, and government relationships, leading to swift political action. In Model (5), cognitive flexibility is significantly positively related to firm performance (γ5 = 0.7827, p < 0.01), and simultaneously, political behavior is also significantly positively related to firm performance (γ6 = 0.2845, p < 0.01). This dual significance provides strong support for Hypothesis 2b. It further clarifies that executives, through their cognitive flexibility, drive strategic political “behavior,” which in turn helps firms secure more external resources, gain a competitive edge, and ultimately improve firm performance. This thoroughly validates the “cognition–behavior–performance” logical framework.

5.5. Heterogeneity Test

In order to explore the boundary conditions of our main findings, we investigated whether the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance varies depending on the internal and external environment of the company.

5.5.1. Differences in Internal Firm Environment

(1) Differences in CEO Overseas Background

As representatives of top management, CEOs’ international experience may shape their cognitive structures, information processing styles, and strategic choice preferences [49], thereby influencing the mechanism through which executive cognitive flexibility affects firm performance. CEOs without an overseas background are often more adapted to the local business environment and have a deeper understanding of the domestic market compared to those with overseas backgrounds. Consequently, their cognitive flexibility may allow them to more swiftly perceive and grasp local market information and make quicker decisions and judgments. Based on this, this study examines whether the CEO has an overseas background (Oversea) as a contextual variable for heterogeneity analysis, assigning a value of 1 to firms where the CEO has an overseas background, and 0 otherwise. The regression results are presented in Table 7, columns (1) and (2). When the CEO has no overseas background, the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is significantly positive. However, for firms where the CEO has an overseas background, the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is not significant.

Table 7.

Internal Environment Heterogeneity Test Results.

(2) Differences in Firm Size

Firm size, being an organizational structural characteristic of utmost significance, may influence the channel by which executive cognitive flexibility influences firm performance via fluctuation in resources, organisational complexity, and market influence. Large firms, due to their enormous organisational breadth and multifaceted operations, need higher levels of macro-strategic direction and complex information processing capability from their top executives [50]. In these firms, cognitive flexibility might be of greater strategic value. Conversely, small firms, with their limited resources and flatter organizational structures, will be highly reliant on direct action and velocity of market response as drivers of performance and, therefore, can potentially have divergent paths to executive cognitive flexibility. Firm size is thus introduced into this paper as a factor to be examined. Based on Shen and Yin’s [51] work, the firm size is calculated by the natural logarithm of total assets. Large firms whose size is greater than the mean are assigned the value of 1; the rest are assigned 0. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 7 report the results. The impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is positive and significant in big firms. However, in small businesses, this effect is minimal. This implies that bigger companies require executives to demonstrate more macro-level regulation, as well as complex problem-solving abilities, where cognitive flexibility is the core element.

(3) Differences in Executive Concurrent Positions

Considering that high-level managers’ external relationships and potential conflicts of interest may significantly influence the application of their cognitive flexibility and its impact on firm performance, this paper introduces a context variable: whether DSSE simultaneously occupies offices in shareholder units for heterogeneity analysis. Where DSSE simultaneously occupies offices in shareholder units, it is threatened with dual agency relationships and multiple objective conflicts [52]. This dual commitment may lead to a diversion of executives’ strategic attention and cognitive effort in the process of strategic decision-making. That is, their decisions would be more obviously influenced by the specific interests of the shareholder unit, rather than by a sole motivation to maximize the aggregate interest of the firm. This potential entanglement of interests and mental bias could compromise the independence and effectiveness of executive cognitive flexibility in improving overall firm performance, essentially transforming the direct impact mechanism of cognitive flexibility on firm performance. We included Executive Concurrent Positions (IsCocurP) in further analysis in compliance with the research of Yan et al. [53]. This variable equals 1 if and only if any DSSE holds a position in a shareholder unit at the same time, and 0 otherwise. The estimated regression results presented in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 7 indicate that the net effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is significant when DSSE is not holding a concurrent position in shareholder units. Conversely, when DSSE holds positions in shareholder units at the same time, the main effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance vanishes. This implies that in those firms where DSSE do not hold simultaneous positions in shareholder units, executives are in a better position to apply their cognitive flexibility independently, concentrating on the shared interests of the firm.

5.5.2. Differences in External Firm Environment

(1) Differences in Market Status

Since a firm’s position in its industry is likely to influence its strategy and the latitude available for executive cognitive flexibility to operate, dominant market position firms tend to have more power, more valuable strategic assets, and better access to information [54]. This imbalance in resource endowment and power could provide executives with greater resource allocation discretion and greater strategic adjustment latitude and, hence, lead to a greater impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance. After the affirmation of the significant positive main effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance, this study also investigates the differentiating effect of market status. Following Meng et al. [55], we measured industry status as a percentage of the operating revenue of the firm to total operating revenue in the whole industry. We divided the sample into high and low industry status subgroups according to the median industry status for the purpose of regression analysis. The evidence, with Table 8, Columns (1) and (2), shows that for the group with high industry status, executive cognitive flexibility has a significant positive impact on firm performance at the 1% level. For the group with low industry status, however, this impact is insignificant. This suggests that firms with high industry status are able to reap more information resource benefits, so this executive cognitive flexibility can impact firm performance more directly.

Table 8.

External Environment Heterogeneity Test Results.

(2) Differences in Industry Pollution Attributes

Because the degree of industry pollution for a company is directly related to the environmental regulatory pressure, public scrutiny, and sustainability demands it faces [56], such external non-market influences may have a considerable influence on how executive cognitive flexibility leads to firm performance, especially sustainable performance. Therefore, this research introduces industry pollution level as a heterogeneity analysis contextual variable. Polluting industries tend to face stricter environmental controls, higher social obligations requirements, and stronger public scrutiny. Strategic choices and how well they perform in their non-market activities (e.g., corporate social responsibility expenditures and lobbying) place higher expectations on executives’ mental skills and adaptability. We speculate that in situations of stricter environmental limits, the process by which executive cognitive flexibility influences firm performance could be of a higher order or subject to some constraints. We split the sample between non-heavily polluting and heavily polluting sectors, according to the study by Guo Ye et al. [57]. The regression estimates are provided in Table 8, Columns (3) and (4). We found that the positive correlation between cognitive flexibility and firm performance is significant in non-heavily polluting sectors but not significant in heavily polluting sectors. This indicates that the positive correlation between cognitive flexibility and firm performance mostly occurs in non-heavily polluting sectors.

(3) Differences in Production Factors

Industries vary in their production factor input structures, especially their labor intensity. In non-labor-intensive firms, strategic adjustments and rapid responses to the external environment may be more critical, and executive cognitive flexibility could play a more direct strategic role. In contrast, labor-intensive firms might focus more on standardized processes, human resource management, and cost control in their production and management [58]. For these firms, the demand for executive cognitive flexibility might manifest more in adapting employee management and improving efficiency. This study introduces industry labor intensity as a contextual variable. Following the research by Yin et al. [59], sample firms are categorized into labor-intensive and non-labor-intensive based on their industry sub-codes. The regression results are shown in Table 8, columns (5) and (6). The results indicate that in non-labor-intensive industries, the impact of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is significantly positive. However, in labor-intensive firms, the effect of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is not significant. This suggests that executives in non-labor-intensive firms can flexibly adjust their cognitive frameworks, quickly absorb new information, and promptly reconfigure strategies to adapt to the external environment. Meanwhile, the standardized production and management in labor-intensive firms weaken the role of executive cognitive flexibility in firm performance.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. General Conclusions and Recommendations

When juxtaposed against the conditions of rising competition worldwide, growing uncertainty, and China’s dizzying economic evolution with an enhanced interest in sustainable development, companies are brought face-to-face with challenges far more complex than those of traditional market competition. Under such conditions, CEOs’ decision-making capability is brought into focus as the focal point of companies’ survival and development challenges. CEOs under such complex conditions would need to exhibit immense cognitive flexibility on their part to excel in rapidly fluctuating business conditions, complex multinational operational project undertakings, and ever-increasingly prominent environmental and social responsibility challenges. This study has drawn upon two basic theories: Upper Echelons Theory and non-market strategy literature. Upper Echelons Theory is concerned with executive individual characteristics that define a company’s strategic choices and performance. Non-market strategy literature, on the other hand, provides explanations of why companies must develop competitive advantages under political, social, and other non-market conditions. Based on an enormous panel database of Chinese A-share listed companies between 2016 and 2022, the present piece of work methodically and exhaustively examines the way executive cognitive flexibility influences firm performance along the root mediator of non-market strategies. It also makes efforts to delineate the boundary conditions of such an effect.

Our empirical analysis yields several key conclusions:

To begin with, executive cognitive flexibility is a positive predictor of firm performance. This result supports the key proposition of upper echelon theory, stressing that the psychological attributes of an executive are a key determinant of organizational performance. Executives who possess greater cognitive flexibility are more capable of dealing with environmental uncertainty, recognizing opportunities, and making successful strategic choices, which is reflected in increased corporate value.

Second, non-market strategies are an essential mediating mechanism in this link, but they do so through different and counterintuitive channels. In particular, we identify that cognitive flexibility improves firm performance by (a) strategically decreasing investment in expensive, high-quality corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, and (b) concurrently elevating participation in corporate political activity (CPA). This reveals a subtle dynamic of strategic resource allocation, with cognitively flexible executives seemingly making pragmatic compromises by diverting resources away from discretionary social expenditures towards political actions with more immediate and concrete returns.

Especially, the differences in the internal and external environments of a firm moderate the influence of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance. When viewed from the internal environmental level, the positive influence of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is stronger in firms with CEOs who do not have overseas backgrounds, implying that an in-depth knowledge of the local market aids cognitive flexibility to be effective. At the same time, this influence is also stronger in large firms, highlighting the fundamental role of macroeconomic strategic control and complicated information processing abilities in large firms. In addition, when executives do not hold concurrent positions in shareholder units, their cognitive flexibility has a more apparent positive influence on firm performance, suggesting the role of independence for cognitive flexibility to be effective. From the external environmental level, the positive influence of executive cognitive flexibility on firm performance is stronger in firms with greater market status, enjoying the advantages of superior information resources. In non-heavily polluting industries, the positive function of cognitive flexibility is also fully realized, implying that environments with lighter environmental regulations and public supervision are more favorable for its effectiveness. Lastly, in non-labor-intensive firms, executive cognitive flexibility’s facilitative influence on firm performance is also stronger because such firms depend more on strategic adaptation and quick reactions to the external environment.

Based on the above research findings, businesses should establish systematic mechanisms for executive cognitive flexibility development and utilization in order to promote sustainable corporate development. At the talent selection and team building level, organizations need to actively select and cultivate executives with high cognitive flexibility and build an organizational climate that encourages multidimensional thinking and balances short-term and long-term interests to address increasingly complex sustainability issues. At the strategic resource allocation level, firms need to deeply integrate market and non-market strategies. That is, they should invest resources in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives directly serving core business operations, namely, highlighting CSR projects with material, sustainable value. In doing so, they prevent the long-term damage resulting from the over-reduction of CSR initiatives. Meanwhile, companies should actively leverage political actions to access differentiated resources and policy support, facilitating green development, innovation, and sustainable transformation. This dual strategy enables dynamic optimization of resource allocation, so when firms pursue economic benefits, they simultaneously generate positive impacts on the environment and society. Moreover, firms should develop differentiated strategic implementation trajectories based on their executive team characteristics, firm size, market status, industry characteristics, production factors, and governance structures to achieve more vigorous and sustainable development: firms should attempt to build an executive team endowed with cognitive diversity and complementary experience to solve sustainable development issues from an integrated perspective; for large firms, investment in executive cognitive flexibility improvement should be made to effectively tackle complex sustainable development programs; firms with a superior market status should fully utilize their resource advantages to opportunistically grasp emerging green market opportunities; firms in high-polluting industries need to leverage executive cognitive flexibility to accelerate green transformation and circular economy conduct and ensure compliance; and firms with non-labor-intensive industries need to invest additional resources in strategic tasks supporting the effectiveness of executive cognitive flexibility, including sustainable technology R&D and innovation. Meanwhile, firms where executives hold concurrent positions need to build more rigorous conflict-of-interest screening and decision-making oversight mechanisms to ensure that executive cognitive flexibility can actually be transformed into long-term firm-level performance improvement and sustainable value creation.

Academically, this study makes the following two contributions: First, this study innovatively introduces executive cognitive flexibility to the field of corporate strategic management to address the shortage of current literature in examining the mechanisms between executive CF and firm performance. We are the first to construct and empirically test the “cognition–behavior–performance” theoretical model, revealing the indirect manner by which executive CF affects firm performance through its influence on non-market strategies (by making optimal investment in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in a strategic way and utilizing Corporate Political Activity (CPA) efficiently). This finding improves our understanding of how executive cognitive traits propel corporate non-market behaviors and their economic consequences for sustainable development. Second, this study meticulously explores the dual mediating mechanisms of corporate political activity and corporate social responsibility in non-market strategies. We not only validate the mediating role of non-market strategy between CF and firm performance, but, more importantly, reveal how, under the condition of resource scarcity and pursuing long-term sustainable development, executive CF drives firms to make strategic, rational reaction to CSR (rather than blind expansion of it, for avoiding resource wastage and enhancing efficiency), and how to effectively utilize CPA to attain policy favor and scarce resources, thereby creating integrated economic, social, and environmental value for the firm. This offers new knowledge on the complexity of non-market strategies and their contextual dependence in supporting corporate sustainable operations. Finally, the study also investigates internal and external environments’ differential moderating influences on the executive CF–firm performance link, providing finer-grained theoretical insight into the boundary conditions under which executive cognitive traits become operative in diverse contexts, particularly when confronting sustainable development issues and opportunities, thus enhancing the application of contextual factors in strategic management research.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Despite having made general contributions, the present study has some limitations that still need to be explored further. Firstly, as the present study is mainly based upon Chinese A-share listed companies, cross-national generalizability of results needs to be evidenced further. This is because national cultural differences potentially might have unique influences upon executive cognitive flexibility and firm strategic actions, and thus their bearing upon firm performance is unknown. Secondly, due to the limitation of the availability of data, the measurement of the present study mainly depends on textual analysis. While all efforts have been undertaken to employ rigor, textual sentiment or semantic analysis might not be capable of capturing the rich cognitive patterns embedded into executive decision-making behaviors appropriately. Hence, future research is advisable to conduct more integrated comparison analysis of firms across various countries and regions to determine the universality of results. Meanwhile, the measuring approach of the executive cognitive flexibility indicator is capable of being further developed, for instance, facilitated by big data models for better capturing executive dynamism or by using a qualitative–quantitative mixed methodology to reduce inaccuracies and poverty of the indicator.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G.; methodology, X.G. and L.T.; software, X.G. and Y.C.; formal analysis, X.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, X.G., L.T., Y.C. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References