Ethical Leadership and Its Impact on Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Role of Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Direct Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Sustainability Performance

2.2. The Direct Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Financial Performance

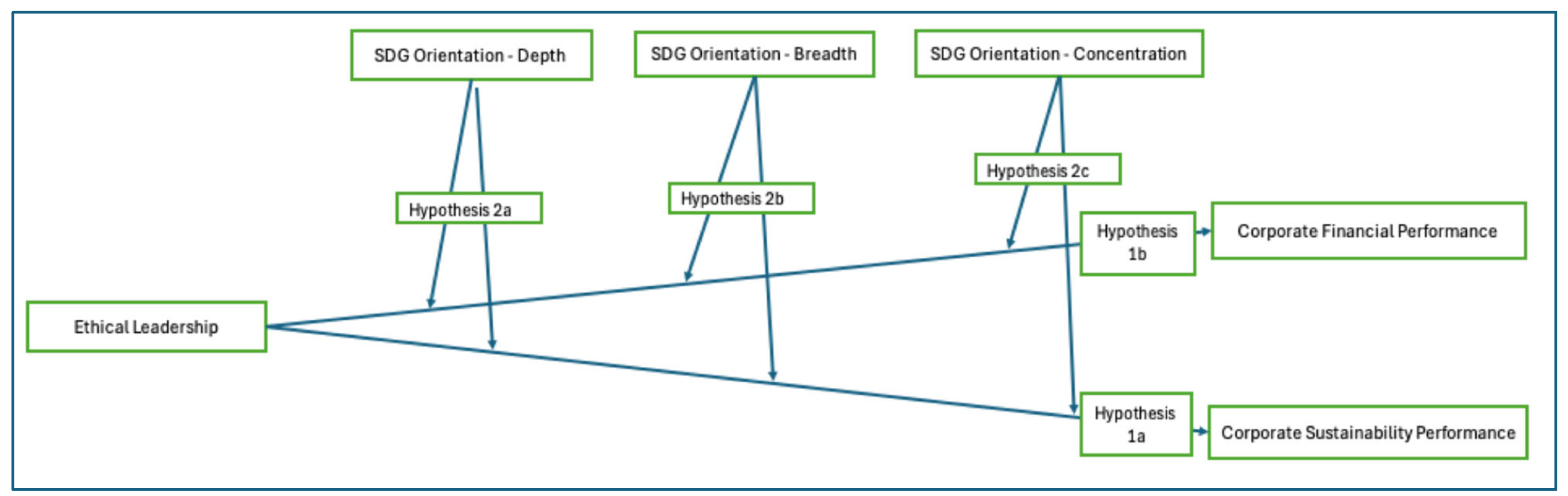

2.3. Moderation Effect of SDG Orientation

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source and Sampling Technique

3.2. Measure

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Firm Performance

3.2.2. Independent Variable: Ethical Leadership

3.2.3. Moderator Variable: Effectiveness of Non-Financial Information

| Variable | Measurement | Description | Recent Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobin’s Q | Market value of a firm’s assets divided by the replacement cost of those assets | Evaluate the market perception of a firm’s value relative to its assets | [16,17,21,29] |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | Percentage (%), net income divided by shareholders’ equity | Financial performance indicator reflecting profitability | [5,16,17,27] |

| Corporate sustainability performance (CSP) | Two different metrics from Refinitiv Eikon and Bloomberg | Rated from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates poor performance and 100 indicates high performance in sustainability-related activities | [28] |

| Ethical leadership | Data from CSRHub | Intangible asset that reflects a firm’s commitment to responsible management and corporate governance | [20,21] |

| Firm Size (FS) | Logarithm of total assets (US$ million) | Controls for resource availability and operational scale | [16,17,21] |

| Leverage | Net debt divided by total equity | Firm’s financial risk | [17,30] |

| Return on equity (ROE) | Dividing net income by shareholders’ equity | Firm’s ability to generate profit from its equity base | [31] |

| Research and Development (R&D) intensity | R&D expenses as a percentage of total sales | Firm’s focus on innovation and long-term growth | [16,17,21,32] |

| Selling, General, and Administrative (SG&A) expenses | Total of operating costs not directly tied to producing goods or services | Day-to-day operating costs not related to production of goods or services | [17,19] |

| Free Cash Flow | Cash generated after operating expenses and capital expenditures | Financial Flexibility | [33,34] |

Depth

Breadth

Concentration

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Estimation Procedures

4. Results and Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

4.2. Ethical Leadership and Firm Performance

4.3. The Moderating Role of SDG-Related Disclosures

4.3.1. Interaction of Ethical Leadership × Disclosure Depth

4.3.2. Interaction of Ethical Leadership × Disclosure Breadth

4.3.3. Interaction of Ethical Leadership × Disclosure Concentration

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Study

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Vocabularies for SDGs

| Sub-Category | Generic Category | Research Definitions | Vocabulary |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 1: No Poverty | Poverty | Refers to conditions of extreme poverty, social protection, and equal access to resources. Target 1.1 to 1.5: Eradicate extreme poverty, reduce vulnerability to climate-related events, and ensure social protection systems. | Poverty, extreme poverty, living in poverty, social protection, equal rights to economic resources, extreme events, income inequality, marginalized communities, social assistance, poverty eradication, social safety nets |

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | Hunger | Encompasses issues related to hunger, nutrition, sustainable food production, and agricultural productivity. Target 2.1 to 2.4: End hunger, ensure sustainable food systems, and improve nutrition. | Hunger, nutrition, end hunger, malnutrition, agricultural productivity, sustainable food production, livestock gene banks, food security, hunger relief, child malnutrition, sustainable agriculture, food accessibility |

| SDG 3: Good Health | Health | Covers general health and well-being, including maternal health, communicable diseases, and other health-related concerns. Target 3.1 to 3.9: Reduce maternal mortality, combat communicable diseases, and promote mental health. | Health, maternal mortality, neonatal mortality, communicable diseases, diseases epidemic, cancer, polio, alcohol, drug, road traffic accidents, reproductive health, health services, air pollution, health equity, universal healthcare, mental health, vaccination, healthcare access, epidemic response |

| SDG 4: Quality Education | Education | Focuses on access to education, early childhood development, and eliminating disparities in educational opportunities. Target 4.1 to 4.7: Ensure inclusive education, equal access, and skills for sustainable development. | Education, primary education, secondary education, childhood development, early childhood, equal access to education, ICT skills, gender disparities in education, literacy, numeracy, sustainable development, inclusive education, lifelong learning, teacher training, vocational training, education infrastructure, e-learning |

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Gender | Addresses gender equality, discrimination, violence against women, and reproductive rights. Target 5.1 to 5.6: Eliminate discrimination, end violence against women, and ensure full participation in leadership. | Gender equality, discrimination, violence against women, genital mutilation, domestic work, equal opportunities for leadership, reproductive rights, women’s empowerment, gender mainstreaming, gender pay gap, leadership parity, equal opportunities |

| SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation | Water | Deals with equitable access to clean water, sanitation services, and sustainable water management. Target 6.1 to 6.6: Ensure safe water, improve sanitation, and protect water-related ecosystems. | Access to clean water, sanitation services, hygiene management, sustainable water use, water quality, integrated water resources management, water scarcity, wastewater treatment, clean drinking water, sanitation facilities, water conservation, hygiene promotion |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | Energy | Covers the availability and accessibility of renewable and sustainable energy resources. Target 7.1 to 7.3: Ensure universal access to energy, improve energy efficiency, and increase renewable energy. | Energy, reliable energy services, renewable energy, energy efficiency, international support, solar energy, wind power, energy storage, energy grid, sustainable electricity, green technology |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | Work & Growth | Focuses on economic growth, decent work, and improved productivity. Target 8.1 to 8.8: Promote sustainable economic growth, full employment, and decent work for all. | Economic growth, GDP growth, domestic financial systems, economic productivity, resource efficiency, decent work, youth employment, forced labor, safe working environment, sustainable tourism, labor rights, employment opportunities, inclusive growth, productivity enhancement, decent wages, small enterprises |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Industry | Pertains to sustainable industrial development, infrastructure, and fostering innovation. Target 9.1 to 9.5: Develop sustainable infrastructure, support innovation, and promote inclusive industrialization. | Infrastructure, sustainable infrastructure, sustainable industrialization, access to financial services, resource-use efficiency, research and development, technological innovation, resilient infrastructure, industrial diversification, R&D investment, digital transformation |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | Inequality | Deals with addressing disparities in income, equal opportunity, and global financial regulations. Target 10.1 to 10.7: Reduce income inequality, empower marginalized communities, and ensure equal opportunities. | Inequality, income growth, social inclusion, equal opportunity, greater equality, regulation of global financial markets, voting rights, economic inclusion, marginalized groups, anti-discrimination policies, wealth distribution, social equity |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | Cities | Focuses on urban development, sustainable housing, and improved city infrastructure. Target 11.1 to 11.7: Ensure access to housing, improve urban planning, and enhance urban resilience. | City, human settlement, sustainable city, adequate housing, transport system, sustainable urbanization, cultural and natural heritage, disaster management, air quality, public space, affordable housing, resilient urban planning, smart cities, urban resilience, green spaces, public transportation |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Consumption | Encourages sustainable practices in consumption and the efficient use of resources. Target 12.1 to 12.8: Promote sustainable consumption patterns, reduce waste, and encourage resource efficiency. | Sustainable consumption, sustainable production, natural resources, food waste, chemicals, recycling, integrated report, sustainable practices, citizenship education, waste management, circular economy, sustainable supply chains, eco-friendly products, responsible sourcing |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | Climate | Focuses on addressing climate change, reducing greenhouse gases, and building resilience to natural disasters. Target 13.1 to 13.3: Strengthen resilience to climate change, integrate climate measures, and improve awareness. | Climate change, natural disaster, greenhouse gases, adaptation, mitigation, carbon neutrality, climate resilience, greenhouse gas reduction, climate adaptation strategies, emissions reduction |

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | Water Ecosystems | Pertains to marine ecosystems, ocean health, and reducing marine pollution. Target 14.1 to 14.7: Prevent marine pollution, manage coastal ecosystems, and conserve marine biodiversity. | Life below water, marine pollution, marine ecosystems, ocean acidification, overfishing, coastal ecosystem, illegal fishing, marine resource, sustainable fisheries, marine biodiversity, coastal protection, ocean conservation, marine protected areas |

| SDG 15: Life on Land | Land Ecosystems | Deals with terrestrial ecosystems, forest conservation, and combating desertification. Target 15.1 to 15.9: Conserve forest areas, restore ecosystems, and combat land degradation. | Life on land, forest, deforestation, desertification, mountain ecosystem, biodiversity loss, terrestrial ecosystem, wildlife trade, alien species, biodiversity, reforestation, habitat preservation, soil erosion control, wildlife protection, ecosystem restoration |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions | Governance | Focuses on promoting peaceful societies, combating corruption, and ensuring inclusive institutions. Target 16.1 to 16.10: Reduce violence, combat corruption, promote inclusive institutions, and ensure access to justice. | Peace, violence, freedoms, abuse, exploitation, justice, illicit arms, corruption, transparency, institution, developing countries in international organizations, legal identity, rule of law, anti-corruption measures, judicial independence, human rights advocacy, access to justice, legal reforms |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | Partnerships | Pertains to international cooperation, sustainable partnerships, and capacity building. Target 17.1 to 17.19: Strengthen global partnerships, enhance policy coherence, and improve international trade and financing for development. | Global partnership, domestic capacity improvement, trading systems, export support for developing countries, transparent imports, macroeconomic stability, policy coherence, partnerships, sustainable development indicators, technology cooperation, environmental technologies, long-term debt sustainability, cross-sectoral partnerships, development financing, multi-stakeholder initiatives, technology transfer, policy advocacy, international trade support |

References

- Awonaike, O.M.; Atan, T. Exploring the Interplay of Stakeholder Pressure, Environmental Awareness, and Environmental Ethics on Perceived Environmental Performance: Insights from the Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Ting, C.W.; Chang, T.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Yen, S.J. The impact of ethical leadership on financial performance: The mediating role of environmentally proactive strategy and the moderating role of institutional pressure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Ioannou, I. Stakeholders and corporate sustainability. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 589–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Influence of environmentally specific transformational leadership on employees’ green innovation behavior—A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, L. The influence of ethical leadership and green organizational identity on Employees’ green innovation behavior: The moderating effect of strategic flexibility. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Zafra-Gómez, J.L. Sustainable governance and corporate performance: The moderating role of disclosure strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis and redirection of research on the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Ann. Arbor. 2007, 1001, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, D.M.; Aquino, K.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Kuenzi, M. Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHares, A. Does Financial Performance Improve the Quality of Sustainability Reporting? Exploring the Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHares, A. Corporate governance mechanisms and R&D intensity in OECD courtiers. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 863–885. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tian, Y.X.; Han, M.H. Recycling mode selection and carbon emission reduction decisions for a multi-channel closed-loop supply chain of electric vehicle power battery under cap-and-trade policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 134060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHares, A. Corporate governance and cost of capital in OECD countries. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2020, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHares, A. Impact of corporate governance and social responsibility on credit risk. Front. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1588468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate social responsibility: An overview and new research directions: Thematic issue on corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firer, C.; Williams, S.M. Intellectual capital and traditional measures of corporate performance. J. Intellect. Cap. 2003, 4, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Society 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevoznic, F.M.; Dragomir, V.D. Achieving the 2030 Agenda: Mapping the Landscape of Corporate Sustainability Goals and Policies in the European Union. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C. Determinants of corporate borrowing. J. Financ. Econ. 1977, 5, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The cross-section of expected stock returns. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschey, M.; Weygandt, J. Amortization policy for advertising and research and development expenditures. J. Account. Res. 1985, 23, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.A.; Aljughaiman, A.A. Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Moderating Effect of CEO Characteristics. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Banker, R.D.; Janakiraman, S.N. Are selling, general, and administrative costs “sticky“? J. Account. Res. 2003, 41, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J. 2009, 9, 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bover, O. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Boechat, A.C. How Sustainable Leadership Can Leverage Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcă, V.; Bogdan, O.; Bunget, O.-C.; Dumitrescu, A.-C. Corporate Financial Performance vs. Corporate Sustainability Performance, between Earnings Management and Process Improvement. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, G. Evaluating Executives and Non-Executives’ Impact toward ESG Performance in Banking Sector: An Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Observation | Mean | SD | Max | Min | ROA | Tobin’s Q | CSP_R | CSP_B | Ethical Leadership | Depth (SDG) | Breadth (SDG) | Concentration (SDG) | Size | Leverage | RD Intensity | SG&A | Free Cash Flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 4200 | 5.31 | 1.523 | 0.241 | 9.451 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Tobin’s Q | 4200 | 1.712 | 0.724 | 0.013 | 8.567 | 0.571 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| CSP_R | 4200 | 56.65 | 15.18 | 94 | 13 | 0.421 *** | 0.389 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| CSR_B | 4200 | 56.65 | 15.18 | 94 | 13 | 0.421 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.121 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Ethical Leadership | 4200 | 45.86 | 12,34 | 90 | 23 | −0.284 *** | 0.323 *** | 0.129 *** | 0.129 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Depth (SDG) | 4200 | 0.346 | 0.125 | 0.745 | 0 | 0.129 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.074 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.229 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| Breadth (SDG) | 4200 | 0.332 | 0.214 | 0.781 | 0 | 0.199 *** | 0.376 *** | 0.647 *** | 0.887 *** | 0.274 *** | 0.721 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| Concentration (SDG) | 4200 | 0.168 | 0.365 | 0.893 | 0 | −0.213 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.431 *** | 0.571 *** | −0.248 *** | −0.585 *** | 0.820 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| Size | 4200 | 16.808 | 1.394 | 16.808 | 16.808 | 0.185 *** | 0.094 *** | 0.110 *** | 0.152 *** | 0.031 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.235 *** | 0.186 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| Leverage | 4200 | 0.226 | 16.101 | 0.226 | 0.226 | 0.008 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.311 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.019 *** | −0.007 *** | 1.000 | |||

| RD Intensity | 4200 | 0.012 | 0.042 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.365 *** | 0.220 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.675 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.246 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.060 *** | 0.002 *** | 1.000 | ||

| SG&A | 4200 | 0.055 | 0.086 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.231 *** | 0.145 *** | 0.411 *** | 0.121 *** | 0.065 *** | 0.122 *** | 0.152 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.184 *** | −0.011 *** | 0.092 *** | 1.000 | |

| Free Cash Flow | 4200 | 0.375 | 0.483 | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.296 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.775 *** | 0.148 *** | 0.172 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.278 *** | −0.045 *** | 0.197 *** | 0.121 *** | 1.000 |

| Baseline Model | Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Financial Performance | Corporate Sustainability Performance | Corporate Financial Performance | Corporate Sustainability Performance | |||||

| Variables | ROA | Tobin’s Q | CSP_R | CSP_B | ROA | Tobin’s Q | CSP_R | CSP_B |

| ROA(t−1) | 0.256 *** (0.045) | 0.231 * (0.031) | ||||||

| Tobin’s Q(t−1) | 0.191 *** (0.023) | 0.554 * (0.062) | ||||||

| CSP_R(t−1) | 0.474 *** (0.056) | 0.156 *** (0.038) | ||||||

| CSP_B(t−1) | 0.305 *** (0.039) | 0.121 ** (0.028) | ||||||

| Ethical Leadership | 0.296 *** (0.028) | 0.455 *** (0.037) | 0.363 *** (0.022) | 0.522 *** (0.038) | ||||

| Size | −0.261 *** (0.007) | −0.747 *** (0.0003) | −0.3464 *** (0.009) | −0.9189 *** (0.011) | −0.000161 (0.005) | 0.180 * (0.026) | 0.398 ** (0.043) | 0.271 ** (0.033) |

| Leverage | 0.110 * (0.021) | 0.328 *** (0.0037) | 0.201 *** (0.009) | 0.421 *** (0.011) | 0.190 * (0.025) | 0.428 (0.041) | 0.101 (0.023) | 0.0421 * (0.013) |

| RD Intensity | 0.141 * (0.017) | 0.213 * (0.023) | 0.441 * (0.036) | 0.1013 * (0.012) | 0.241 * (0.027) | 0.4313 * (0.039) | 0.541 * (0.046) | 0.2513 * (0.028) |

| SG&A | 0.379 * (0.033) | 0.257 * (0.021) | 0.143 * (0.021) | 0.722 *** (0.017) | 0.479 * (0.037) | 0.307 (0.032) | 0.343 * (0.024) | 0.222 (0.019) |

| Free Cash Flow | 0.026 *** (0.006) | 2.067 *** (0.215) | 0.078 * (0.012) | 0.395 (0.033) | 0.096 * (0.015) | 0.187 * (0.027) | 0.058 *** (0.008) | 0.533 *** (0.041) |

| Constant | 0.356 * (0.045) | 2.234 (0.156) | 3.155 (0.201) | 0.655 (0.071) | 0.556 * (0.062) | 1.134 (0.102) | 0.355 (0.049) | 0.655 *** (0.058) |

| Country | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 |

| Number of firms | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 |

| No of Instruments | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 |

| AR(1) | −0.148 (0.038) | −2.25 (0.024) | −2.13 (0.061) | −3.25 (0.005) | −0.118 (0.001) | −3.25 (0.004) | −4.03 (0.044) | −5.85 (0.014) |

| AR(2) | 2.28 (0.321) | 0.54 (0.642) | 0.011 (0.693) | 0.69 (0.451) | 4.18 (0.213) | 0.74 (0.744) | 0.611 (0.713) | 0.69 (0.655) |

| Hansen Test | 22.31 (0.358) | 12.80 (0.139) | 42.65 (0.749) | 35.57 (0.345) | 2.31 (0.358) | 2.80 (0.232) | 2.65 (0.846) | 6.57 (0.343) |

| Hansen Different Test | 2.01 (0.140) | 12.108 (0.313) | 20.48 (0.138) | 7.39 (0.125) | 3.01 (0.140) | 9.108 (0.435) | 0.48 (0.138) | 10.39 (0.422) |

| Sargan Test | 18.5 (0.274) | 16.4 (0.341) | 30.8 (0.667) | 21.1 (0.514) | 28.4 (0.242) | 22.8 (0.527) | 16.6 (0.433) | 33.2 (0.645) |

| Wald Test (χ2) | 44.3 (0.000) | 34.1 (0.000) | 28.8 (0.000) | 30.6 (0.000) | 53.1 (0.000) | 43.5 (0.000) | 38.2 (0.000) | 37.7 (0.000) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ROA | Tobin’s Q | CSP_R | CSP_B | ROA | Tobin’s Q | CSP_R | CSP_B | ROA | Tobin’s Q | CSP_R | CSP_B |

| ROA(t−1) | 0.326 ** (0.049) | 0.505 ** (0.051) | 0.385 * (0.043) | |||||||||

| Tobin’s Q(t−1) | 0.301 * (0.039) | 0.706 * (0.068) | 0.276 *** (0.041) | |||||||||

| CSP_R(t−1) | 0.624 ** (0.069) | 0.651 *** (0.049) | 0.211 ** (0.032) | |||||||||

| CSP_B(t−1) | 0.475 ** (0.053) | 0.714 *** (0.060) | 0.264 ** (0.053) | |||||||||

| Ethical Leadership | 0.358 * (0.033) | 0.527 ** (0.043) | 0.425 * (0.028) | 0.594 ** (0.044) | 0.548 ** (0.036) | 0.747 *** (0.049) | 0.491 ** (0.031) | 0.701 ** (0.050) | 0.582 ** (0.041) | 0.828 *** (0.053) | 0.454 ** (0.027) | 0.723 ** (0.055) |

| Disclosure Depth | 0.361 ** (0.030) | 0.185 * (0.019) | 0.1264 * (0.016) | 0.209 ** (0.027) | ||||||||

| Disclosure Breadth | 0.416 ** (0.059) | 0.251 ** (0.028) | 0.514 ** (0.061) | 0.395 * (0.046) | ||||||||

| Disclosure Concentration | 0.351 ** (0.046) | 0.205 * (0.034) | 0.534 ** (0.042) | 0.639 ** (0.048) | ||||||||

| Ethical Leadership × Depth | 0.334 * (0.025) | 0.383 ** (0.034) | 0.257 * (0.016) | 0.425 ** (0.031) | ||||||||

| Ethical Leadership × Breadth | 0.276 * (0.020) | 0.439 ** (0.035) | 0.363 * (0.025) | 0.397 ** (0.032) | ||||||||

| Ethical Leadership × Concentration | 0.427 ** (0.030) | 0.548 ** (0.043) | 0.384 ** (0.023) | 0.563 ** (0.041) | ||||||||

| Size | 0.096 ** (0.008) | 2.237 ** (0.239) | 0.148 * (0.015) | 0.465 ** (0.038) | 0.166 * (0.019) | 0.257 ** (0.031) | 0.128 * (0.011) | 0.096 ** (0.008) | 2.237 ** (0.239) | 0.148 * (0.015) | 0.465 ** (0.038) | 0.166 * (0.019) |

| Leverage | 0.260 ** (0.030) | 0.498 ** (0.045) | 0.171 * (0.027) | 0.1121 * (0.017) | 0.560 ** (0.040) | 0.898 ** (0.060) | 0.181 * (0.033) | 0.481 ** (0.044) | 0.658 ** (0.052) | 0.868 ** (0.069) | 0.191 * (0.021) | 0.491 ** (0.026) |

| RD Intensity | 0.311 * (0.031) | 0.5013 ** (0.044) | 0.611 ** (0.052) | 0.3213 * (0.029) | 0.611 ** (0.035) | 0.883 ** (0.051) | 0.851 ** (0.056) | 0.9213 ** (0.058) | 0.701 * (0.043) | 0.893 ** (0.055) | 0.761 ** (0.049) | 0.9113 ** (0.061) |

| SG&A | 0.549 ** (0.042) | 0.377 ** (0.034) | 0.413 * (0.027) | 0.292 * (0.022) | 0.3279 ** (0.035) | 0.777 ** (0.050) | 0.663 ** (0.044) | 0.512 ** (0.034) | 0.5179 ** (0.040) | 0.697 ** (0.046) | 0.673 ** (0.044) | 0.522 ** (0.031) |

| Free Cash Flow | 0.166 * (0.019) | 0.257 ** (0.031) | 0.128 * (0.011) | 0.603 ** (0.046) | 0.796 ** (0.064) | 0.387 ** (0.040) | 0.218 ** (0.026) | 0.865 ** (0.068) | 0.296 ** (0.023) | 0.317 ** (0.034) | 0.198 * (0.018) | 0.837 ** (0.050) |

| Constant | 0.626 ** (0.075) | 1.204 ** (0.118) | 0.425 ** (0.056) | 0.725 ** (0.067) | 0.626 ** (0.051) | 0.756 ** (0.059) | 3.325 ** (0.194) | 0.825 ** (0.090) | 0.216 ** (0.046) | 3.306 ** (0.234) | 0.625 ** (0.081) | 0.695 ** (0.060) |

| Country | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 | 4200 |

| Number of firms | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 |

| No of Instruments | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 | 67 |

| AR(1) | −0.138 (0.004) | −3.55 (0.006) | −4.23 (0.048) | −6.65 (0.016) | −1.178 (0.031) | −4.55 (0.016) | −6.53 (0.062) | −9.15 (0.020) | −1.298 (0.036) | −4.35 (0.020) | −6.93 (0.059) | −9.75 (0.020) |

| AR(2) | 4.38 (0.293) | 0.84 (0.814) | 0.711 (0.783) | 0.79 (0.725) | 4.28 (0.493) | 1.74 (0.811) | 0.261 (0.863) | 0.78 (0.515) | 4.38 (0.501) | 1.84 (0.813) | 0.251 (0.861) | 0.88 (0.519) |

| Hansen Test | 10.31 (0.438) | 10.80 (0.312) | 10.65 (0.916) | 14.57 (0.423) | 50.31 (1.425) | 40.80 (0.618) | 30.65 (0.864) | 24.57 (0.725) | 50.51 (1.431) | 40.60 (0.622) | 30.45 (0.861) | 24.77 (0.729) |

| Hansen Different Test | 11.01 (0.220) | 17.108 (0.515) | 8.48 (0.218) | 19.39 (0.502) | 30.01 (0.422) | 20.108 (0.313) | 32.48 (0.707) | 25.39 (0.802) | 30.21 (0.426) | 20.308 (0.316) | 32.68 (0.704) | 25.49 (0.805) |

| Sargan Test | 36.4 (0.322) | 30.8 (0.597) | 24.6 (0.503) | 41.2 (0.715) | 30.7 (0.602) | 28.4 (0.469) | 34.8 (0.673) | 33.2 (0.650) | 30.5 (0.605) | 28.8 (0.471) | 34.5 (0.676) | 33.5 (0.652) |

| Wald Test (χ2) | 61.1 (0.000) | 51.5 (0.000) | 46.2 (0.000) | 45.7 (0.000) | 67.8 (0.000) | 63.2 (0.000) | 49.1 (0.000) | 55.3 (0.000) | 69.3 (0.000) | 63.5 (0.000) | 50.1 (0.000) | 56.3 (0.000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlHares, A. Ethical Leadership and Its Impact on Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Role of Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156682

AlHares A. Ethical Leadership and Its Impact on Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Role of Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156682

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlHares, Aws. 2025. "Ethical Leadership and Its Impact on Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Role of Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156682

APA StyleAlHares, A. (2025). Ethical Leadership and Its Impact on Corporate Sustainability and Financial Performance: The Role of Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 17(15), 6682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156682