Corporate Social Responsibility as a Buffer in Times of Crisis: Evidence from China’s Stock Market During COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

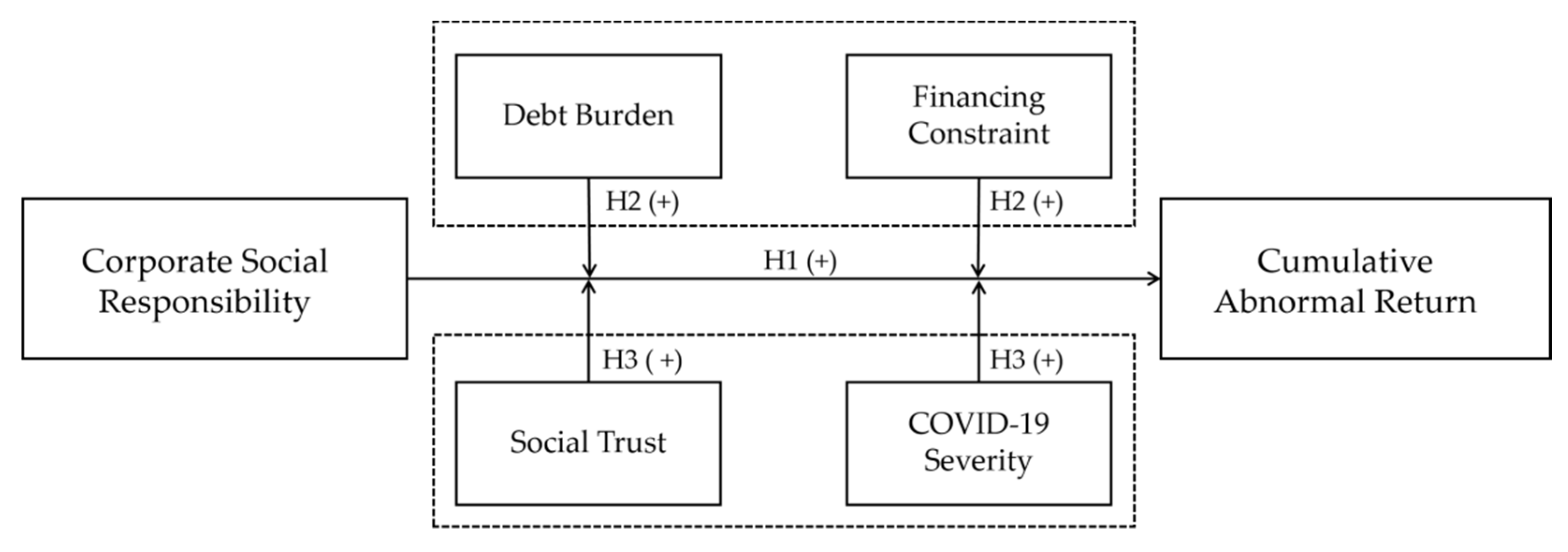

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Techniques, Sample Selection, and Data Sources

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Basic Regression Results

4.2.1. The Buffering Effect of CSR on COVID-19 Shocks

4.2.2. Comparison of Subgroups Based on Level of Over-Indebtedness

4.2.3. Comparison of Subgroups Based on the Degree of Financing Constraints

4.3. Cross-Sectional Analysis

4.3.1. Regional Trust Levels

4.3.2. Regional Severity of COVID-19

4.4. Analysis of Differences in the Role of Sub-Dimensional CSR

4.5. Robustness Tests

4.5.1. Change CSR Definition

4.5.2. Change Event Window

4.5.3. Change Grouping Method

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Chinese-Context Insights

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Guo, J.; Wang, H. Corporate social responsibility, financing constraints and corporate financialization. J. Financ. Res. 2020, 2, 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Xiao, T.; Chen, X. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate finance constraints. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 38, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y. Stakeholder pressure, corporate social responsibility and corporate value. Chin. J. Manag. 2016, 13, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, G.; Doellgast, V.; Baccaro, L. Corporate social responsibility and labour standards: Bridging business management and employment relations perspectives. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2018, 56, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. Corporate social responsibility, market evaluation and surplus information content. Account. Res. 2011, 11, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Demers, E.; Hendrikse, J.; Joos, P.; Lev, B. ESG didn’t immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but investments in intangible assets did. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2021, 48, 433–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beddewela, E.; Fairbrass, J. Seeking legitimacy through CSR: Institutional pressures and corporate responses of multinationals in Sri Lanka. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Vieira, E.T. Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights from oil companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. CSR-based political legitimacy strategy: Managing the state by doing good in China and Russia. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, E.; Nirino, N.; Leonidou, E.; Thrassou, A. Corporate venture capital and CSR performance: An extended resource based view’s perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. A bibliometric and thematic analysis of the reputation-performance relationship within the triple bottom line framework. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2025, 31, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, A.; Krumay, B. The good, the bad, and the successful-How corporate social responsibility leads to competitive advantage and organizational transformation. J. Change Manag. 2013, 13, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Fang, Y. An empirical study on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A panel data analysis from stakeholder perspective. China Ind. Econ. 2008, 1, 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ursic, D.; Cestar, A.S. Crisis management and CSR in Slovenian companies: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, D.; Visentin, G. CSR in times of crisis: A systematic literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinot, J. Changing the Economic Paradigm: Towards a Sustainable Business Model. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Xiao, X.; Cheng, X. The effect of social responsibility on corporate risk: An analysis based on China’s economic environment. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2016, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.W.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferriani, F.; Natoli, F. ESG risks in times of COVID-19. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2020, 28, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T.; McDonald, B. Management disclosure of risk factors and COVID-19. Financ. Innov. 2023, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garel, A.; Petit-Romec, A. The resilience of French companies to the COVID-19 crisis. Finance 2021, 42, 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, K. The “Masking effect” of social responsibility disclosure and the risk of crash of listed companies: A DID-PSM analysis from Chinese stock market. J. Manag. World 2017, 11, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Masulis, R.W.; Reza, S.W. Agency problems of corporate philanthropy. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 592–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva Abadía, J.M.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. Corporate social responsibility as a strategic opportunity for small firms during economic crises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 172–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.; El Ghoul, S.; Gong, Z.; Guedhami, O. Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Yamada, K. When the Japanese stock market meets COVID-19: Impact of ownership, China and US exposure, and ESG channels. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 74, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wiersema, M.F. Stock market reaction to CEO certification: The signaling role of CEO background. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y. COVID-19 outbreak and financial performance of Chinese listed firms: Evidence from corporate culture and corporate social responsibility. Front. Public. Health 2021, 9, 710743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Y. Kindness is rewarded! The impact of corporate social responsibility on Chinese market reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ. Lett. 2021, 208, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y. Restart economy in a resilient way: The value of corporate social responsibility to firms in COVID-19. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garel, A.; Petit-Romec, A. Investor rewards to environmental responsibility: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 68, 101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and firm value: A signaling theory perspective. J. Econ. Dev. 2025, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Liu, X. Research on several major financial issues from the perspective of corporate social responsibility based on stakeholder theory. Wuhan Univ. J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2009, 6, 794–799. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetta, D. Can we Trust Trust? In Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations; Gambetta, D., Ed.; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Zhou, Z. Female executives, trust environment and corporate social responsibility information disclosure: Empirical evidence based on A-share listed companies voluntarily disclosing social responsibility reports. J. Audit. Econ. 2015, 30, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Scrivens, K.; Smith, C. Four Interpretations of Social Capital: An Agenda for Measurement; OECD Statistics Working Papers: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Evan, W.M. Corporate governance: A stakeholder interpretation. J. Behav. Econ. 1990, 19, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, R. An empirical study of corporate social responsibility and its impact on corporate social capital in China. China Soft Sci. 2009, 11, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X. Does corporate social responsibility affect social capital? A study on the regulatory role based on market competition and legal system. China Soft Sci. 2018, 2, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Yin, K. Research on corporate social responsibility issues from the perspective of stakeholders. China Soft Sci. 2012, 2, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Luo, W.; Xiao, W. Corporate social responsibility behavior and consumer response: Moderating consumers’ individual characteristics and price signals. China Ind. Econ. 2007, 3, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Z. An empirical study on the impact of CSR on corporate reputation and customer loyalty. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2010, 13, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, C. Resiliency of environmental and social stocks: An analysis of the exogenous COVID-19 market crash. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, N.P. Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2007, 42, 683–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. Is ethical money financially smart? Nonfinancial attributes and money flows of socially responsible investment funds. J. Financ. Int. 2011, 20, 562–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, V.; Ibrushi, D.; Zhao, J. Reconsidering systematic factors during the Covid-19 pandemic-The rising importance of ESG. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiordelisi, F.; Galloppo, G.; Lattanzio, G. Where does corporate social capital matter the most? Evidence From the COVID-19 crisis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 47, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ye, Y. Rethinking capital structure decision and corporate social responsibility in response to COVID-19. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 4757–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnitzki, D.; Hall, B.H.; Hottenrott, H. Patents as Quality Signals? The Implications for Financing Constraints on R&D. SSRN Electron. J. 2014, 25, 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, R.; Khan, M.; Kaleem, M. Skilled managers and capital financing decisions: Navigating Chinese firms through financing constraints and growth opportunities. Kybernetes 2023, 53, 4381–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Financing constraints and firm-level responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: International evidence. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 59, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Jing, T. Does social responsibility reporting reduce the cost of corporate equity capital? Empirical evidence from Chinese capital market. Account. Res. 2013, 9, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; He, J.; Dou, H. Who is more over-indebted: State-owned or non-state-owned enterprises? Econ. Res. J. 2015, 50, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, X.; Lu, D.; Yu, Y. Financing constraints, working capital management and corporate innovation sustainability. Econ. Res. J. 2013, 48, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Latest! Pneumonia of Unknown Cause Was Found in Wuhan! Hospital Person: At Present, It Cannot Be Concluded That It Is a SARS Hot Broadcast. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_5392576 (accessed on 31 December 2019).

- Follow/1 Case Died, and He Was Seriously Ill7 Cases! Wuhan Reported an “Unknown Pneumonia” Situation Condition. Available online: https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_5493080 (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Zhong Nanshan: Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia “Affirms Human-to-Human Transmission”. Available online: https://www.caixin.com/2020-01-20/101506465.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Wuhan Announced Overnight: The Passage from Han Is Temporarily Closed, and It Has Fully Entered a Wartime State! Available online: https://finance.sina.com.cn/stock/zqgd/2020-01-23/doc-iihnzhha4259812.shtml (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Harford, J.; Klasa, S.; Walcott, N. Do Firms Have Leverage Targets? Evidence from Acquisitions. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.; Denis, S.; McKeon, B. Debt Financing and Financial Flexibility Evidence from Proactive Leverage Increases. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2012, 25, 1897–1929. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.; He, Y. A study of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and stock returns in times of crisis. Theory Pract. Financ. Econ. 2021, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| CAR | Cumulative abnormal return, derived using market model |

| CSR | Social responsibility investment, equal to the CSR scores of 2019 from the professional evaluation system of Hexun’s Social Responsibility Report for Listed Companies |

| Size | Firm size, equal to natural logarithm of the book value of total assets |

| Lev | Level of debt, equal to ratio of total debt divided by total asset |

| ROA | Return on assets, equal to net income divided by total assets |

| BM | Book-to-market ratio, equal to total assets divided by market value |

| Tobin | Tobin’s Q |

| Top | Shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder |

| Inddirector | Percentage of independent board members of a company |

| Director | Size of directors, equal to natural logarithm of the total number of directors |

| Dual | If the chairman of board and CEO are the same person, take 1, otherwise take 0 |

| SOE | Nature of property rights, state-owned enterprises take 1, non-state-owned enterprises take 0 |

| Inv_lev | Industry leverage ratio, equal to the median leverage ratio in the industry |

| Growth | Firm growth, equal to total asset growth rate |

| Fata | Fixed asset ratio, equal to net fixed assets divided by total assets |

| Age | Firm age, equal to 2019 minus year the firm was founded |

| Elev | Firms with excessive debts take 1, otherwise take 0 |

| FC | Firms with high financing constraints take 1, otherwise take 0 |

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | 2477 | −0.008 | 0.114 | −0.201 | −0.035 | 0.465 |

| CSR | 2477 | 19.819 | 9.033 | −3.760 | 21.340 | 36.500 |

| Size | 2477 | 22.573 | 1.330 | 19.186 | 22.416 | 26.366 |

| Lev | 2477 | 0.443 | 0.196 | 0.060 | 0.433 | 0.995 |

| ROA | 2477 | 0.029 | 0.091 | −0.705 | 0.034 | 0.258 |

| BM | 2477 | 0.711 | 0.255 | 0.121 | 0.721 | 1.220 |

| Tobin | 2477 | 1.717 | 1.066 | 0.820 | 1.386 | 8.246 |

| Top | 2477 | 0.350 | 0.146 | 0.090 | 0.328 | 0.721 |

| Inddirector | 2477 | 0.378 | 0.054 | 0.333 | 0.364 | 0.571 |

| Director | 2477 | 8.479 | 1.658 | 4.000 | 9.000 | 17.000 |

| Dual | 2477 | 0.266 | 0.442 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | 0.0014 *** | 0.0009 ** |

| (5.23) | (2.27) | |

| Size | 0.0135 *** | |

| (5.81) | ||

| Lev | −0.0406 *** | |

| (−2.62) | ||

| ROA | 0.0231 | |

| (0.48) | ||

| BM | −0.0347 ** | |

| (−2.08) | ||

| Tobin | −0.0026 | |

| (−0.77) | ||

| Top | −0.0516 *** | |

| (−3.27) | ||

| Inddirector | −0.0556 | |

| (−1.27) | ||

| Director | −0.0024 * | |

| (−1.72) | ||

| Dual | 0.0112 ** | |

| (1.99) | ||

| _cons | −0.0368 *** | −0.2283 *** |

| (−6.17) | (−5.14) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES |

| n | 2477 | 2477 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.049 | 0.062 |

| Change in Adj-R2 | -- | 0.013 *** |

| F-statistics | 27.30 *** | 7.95 *** |

| (1) Elev = 0 | (2) Elev = 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | 0.0001 | 0.0014 ** |

| (0.27) | (2.37) | |

| Size | 0.0177 *** | 0.0155 *** |

| (4.96) | (3.88) | |

| Lev | −0.1047 *** | −0.0820 ** |

| (−3.11) | (−2.34) | |

| ROA | 0.0346 | 0.0014 |

| (0.62) | (0.02) | |

| BM | −0.0329 | −0.0357 |

| (−1.56) | (−1.30) | |

| Tobin | −0.0029 | −0.0015 |

| (−0.64) | (−0.30) | |

| Top | −0.0409 * | −0.0670 *** |

| (−1.90) | (−2.78) | |

| Inddirector | −0.0607 | −0.0528 |

| (−1.01) | (−0.80) | |

| Director | −0.0010 | −0.0038 * |

| (−0.53) | (−1.76) | |

| Dual | 0.0101 | 0.0122 |

| (1.27) | (1.48) | |

| _cons | −0.3074 *** | −0.2382 *** |

| (−4.58) | (−3.32) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES |

| Test for coefficient | −0.0013 *** | |

| difference (p-value) | (0.005) | |

| n | 1256 | 1221 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.055 | 0.064 |

| F-statistics | 3.56 *** | 6.61 *** |

| (1) FC = 0 | (2) FC = 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | 0.0006 | 0.0015 *** |

| (0.83) | (2.88) | |

| Size | 0.0137 *** | 0.0151 *** |

| (4.68) | (3.38) | |

| Lev | −0.0145 | −0.0583 *** |

| (−0.65) | (−2.68) | |

| ROA | 0.0039 | 0.0275 |

| (0.04) | (0.59) | |

| BM | −0.0717 *** | −0.0039 |

| (−2.83) | (−0.17) | |

| Tobin | −0.0022 | −0.0030 |

| (−0.38) | (−0.72) | |

| Top | −0.0455 ** | −0.0443 * |

| (−2.08) | (−1.87) | |

| Inddirector | −0.0845 | −0.0226 |

| (−1.32) | (−0.38) | |

| Director | −0.0030 | −0.0018 |

| (−1.49) | (−0.88) | |

| Dual | −0.0004 | 0.0242 *** |

| (−0.06) | (2.74) | |

| _cons | −0.1973 *** | −0.3103 *** |

| (−3.63) | (−3.38) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES |

| Test for coefficient | −0.0009 * | |

| difference (p-value) | (0.056) | |

| n | 1238 | 1239 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.053 | 0.078 |

| F-statistics | 4.19 *** | 7.03 *** |

| (1) Trust = 0 | (2) Trust = 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | 0.0004 | 0.0019 *** |

| (0.82) | (2.95) | |

| Size | 0.0180 *** | 0.0080 ** |

| (5.44) | (2.40) | |

| Lev | −0.0772 *** | 0.0044 |

| (−3.58) | (0.20) | |

| ROA | 0.0548 | −0.0275 |

| (1.09) | (−0.31) | |

| BM | −0.0255 | −0.0449 * |

| (−1.04) | (−1.91) | |

| Tobin | −0.0029 | −0.0030 |

| (−0.64) | (−0.59) | |

| Top | −0.0779 *** | −0.0236 |

| (−3.78) | (−0.93) | |

| Inddirector | −0.0594 | −0.0511 |

| (−1.00) | (−0.76) | |

| Director | −0.0035 * | −0.0014 |

| (−1.87) | (−0.65) | |

| Dual | 0.0143 * | 0.0064 |

| (1.89) | (0.75) | |

| _cons | −0.2917 *** | −0.1526 ** |

| (−4.63) | (−2.39) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES |

| Test for coefficient | −0.0015 ** | |

| difference (p-value) | (0.049) | |

| n | 1322 | 1153 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.071 | 0.046 |

| F-statistics | 7.27 *** | 3.81 *** |

| (1) COVID = 0 | (2) COVID = 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | −0.0001 | 0.0014 ** |

| (−0.13) | (2.00) | |

| Size | 0.0073 | 0.0170 *** |

| (1.32) | (4.44) | |

| Lev | −0.0646 * | −0.0188 |

| (−1.82) | (−0.80) | |

| ROA | 0.0219 | −0.0243 |

| (0.18) | (−0.28) | |

| BM | −0.0075 | −0.0696 ** |

| (−0.19) | (−2.35) | |

| Tobin | −0.0060 | −0.0026 |

| (−0.89) | (−0.42) | |

| Top | 0.0082 | −0.0577 ** |

| (0.21) | (−2.17) | |

| Inddirector | 0.1057 | −0.1020 |

| (0.91) | (−1.49) | |

| Director | −0.0003 | −0.0022 |

| (−0.10) | (−0.95) | |

| Dual | 0.0432 ** | 0.0115 |

| (2.48) | (1.24) | |

| _cons | −0.1809 * | −0.2849 *** |

| (−1.86) | (−3.59) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES |

| Test for coefficient | −0.0015 * | |

| difference (p-value) | (0.099) | |

| n | 452 | 895 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.055 | 0.054 |

| F-statistics | 1.60 | 4.87 *** |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | CAR | |

| CSR_A | 0.0012 * | ||

| (1.93) | |||

| CSR_B | −0.0012 | ||

| (−0.64) | |||

| CSR_E | 0.0012 * | ||

| (1.90) | |||

| Size | 0.0136 *** | 0.0153 *** | 0.0147 *** |

| (5.79) | (6.62) | (6.53) | |

| Lev | −0.0391 ** | −0.0471 *** | −0.0468 *** |

| (−2.47) | (−3.12) | (−3.11) | |

| ROA | 0.0222 | 0.0776 ** | 0.0633 * |

| (0.42) | (2.08) | (1.66) | |

| BM | −0.0346 ** | −0.0389 ** | −0.0380 ** |

| (−2.07) | (−2.31) | (−2.26) | |

| Tobin | −0.0024 | −0.0028 | −0.0029 |

| (−0.73) | (−0.86) | (−0.87) | |

| Top | −0.0522 *** | −0.0463 *** | −0.0471 *** |

| (−3.30) | (−2.92) | (−2.98) | |

| Inddirector | −0.0533 | −0.0569 | −0.0594 |

| (−1.22) | (−1.30) | (−1.35) | |

| Director | −0.0024 * | −0.0024 * | −0.0024 * |

| (−1.70) | (−1.71) | (−1.74) | |

| Dual | 0.0106 * | 0.0113 ** | 0.0118 ** |

| (1.89) | (2.00) | (2.10) | |

| _cons | −0.2307 *** | −0.2453 *** | −0.2385 *** |

| (−5.20) | (−5.53) | (−5.41) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES |

| n | 2477 | 2477 | 2477 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.061 | 0.059 | 0.061 |

| F-statistics | 8.22 *** | 7.06 *** | 7.31 *** |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | 0.0008 * | 0.0010 *** | 0.0009 ** |

| (1.92) | (3.10) | (2.06) | |

| _cons | −0.2274 *** | −0.2680 *** | −0.2135 *** |

| (−5.08) | (−7.25) | (−4.17) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES |

| n | 2477 | 2477 | 2477 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.061 | 0.069 | 0.069 |

| F-statistics | 7.95 *** | 7.95 *** | 7.95 *** |

| (1) Elev = 0 | (2) Elev = 1 | (3) FC = 0 | (4) FC = 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | CAR | CAR | CAR | |

| CSR | 0.0002 | 0.0020 *** | −0.0004 | 0.0017 *** |

| (0.35) | (2.82) | (−0.57) | (2.74) | |

| _cons | −0.3664 *** | −0.2398 ** | −0.1673 *** | −0.2706 ** |

| (−4.30) | (−2.50) | (−2.73) | (−2.16) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Test for coefficient | −0.0018 *** | −0.0021 * | ||

| difference (p-value) | (0.003) | (0.054) | ||

| n | 826 | 825 | 825 | 826 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.056 | 0.066 | 0.044 | 0.079 |

| F-statistics | 3.56 *** | 6.01 *** | 4.19 *** | 7.03 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, D.; Hu, S.; Wang, H. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Buffer in Times of Crisis: Evidence from China’s Stock Market During COVID-19. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146636

Huang D, Hu S, Wang H. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Buffer in Times of Crisis: Evidence from China’s Stock Market During COVID-19. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146636

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Dongdong, Shuyu Hu, and Haoxu Wang. 2025. "Corporate Social Responsibility as a Buffer in Times of Crisis: Evidence from China’s Stock Market During COVID-19" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146636

APA StyleHuang, D., Hu, S., & Wang, H. (2025). Corporate Social Responsibility as a Buffer in Times of Crisis: Evidence from China’s Stock Market During COVID-19. Sustainability, 17(14), 6636. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146636