The Public Acceptance of Power-to-X Technologies—Results from Environmental–Psychological Research Using a Representative German Sample

Abstract

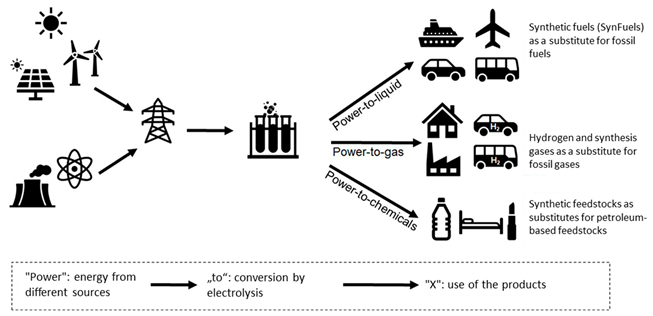

1. Introduction

1.1. Influencing Factors of the Acceptance of PtX

1.2. Who Is Accepting? Why Young People Are Central for the Energy System Transition

- 1.

- What is the current level of public knowledge regarding ptx technologies?

- a.

- Which characteristics or perceptions are associated with this perception?

- 2.

- To what extent are ptx technologies accepted by the public overall, and how do perceptions vary across different fields of application?

- a.

- What conditions must be met for ptx technologies to be accepted by the public (i.e., what constitutes conditional acceptance)?

- b.

- Which factors—technical, psychological, or socio-demographic—influence the public acceptance of ptx technologies? How do these factors differ across specific sectors such as mobility, industry, and chemical production?

- 3.

- In what ways do the acceptance levels and influencing factors differ between younger individuals and adults?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Approach and Construct Evaluation

3. Results

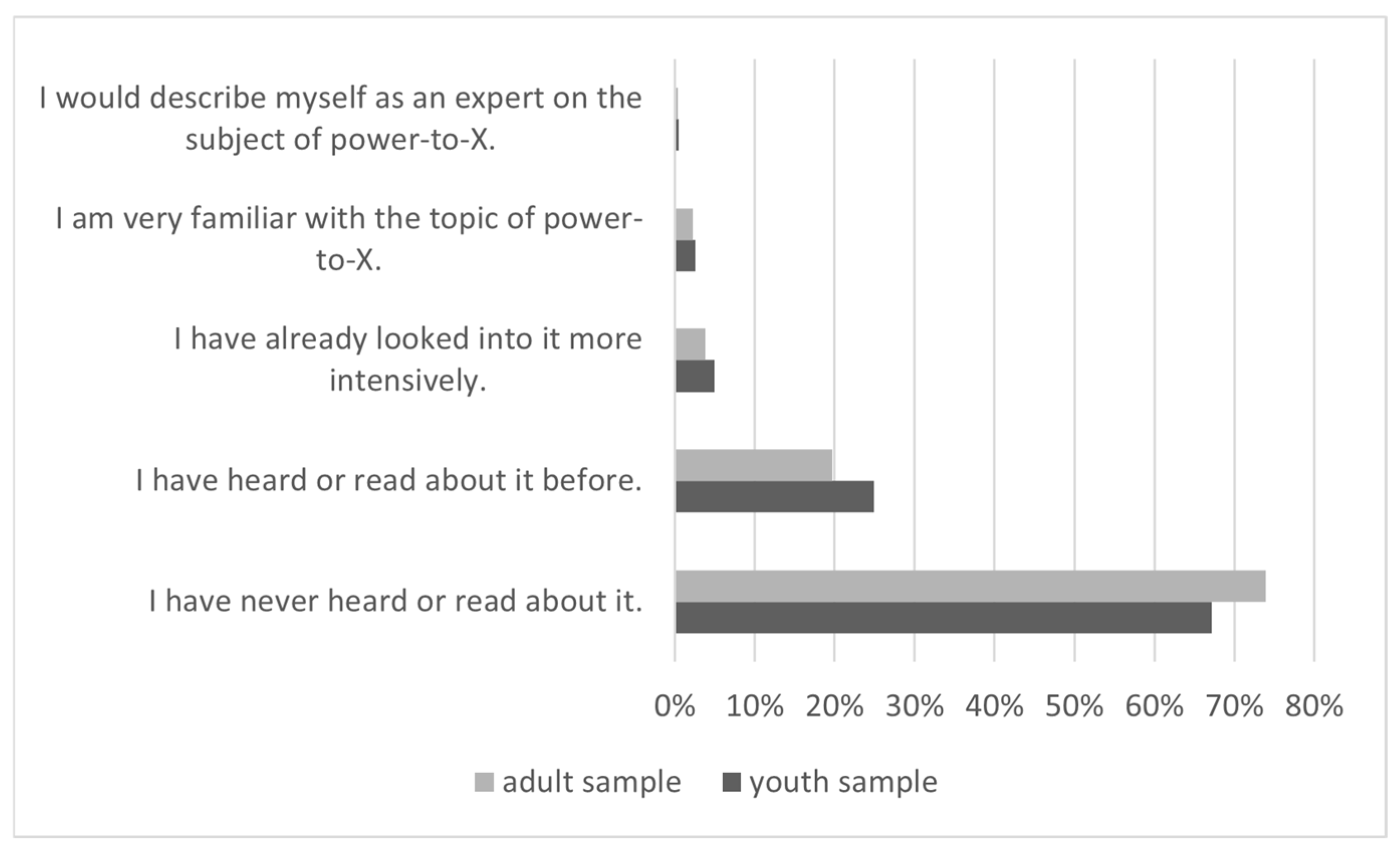

3.1. Prior Knowledge

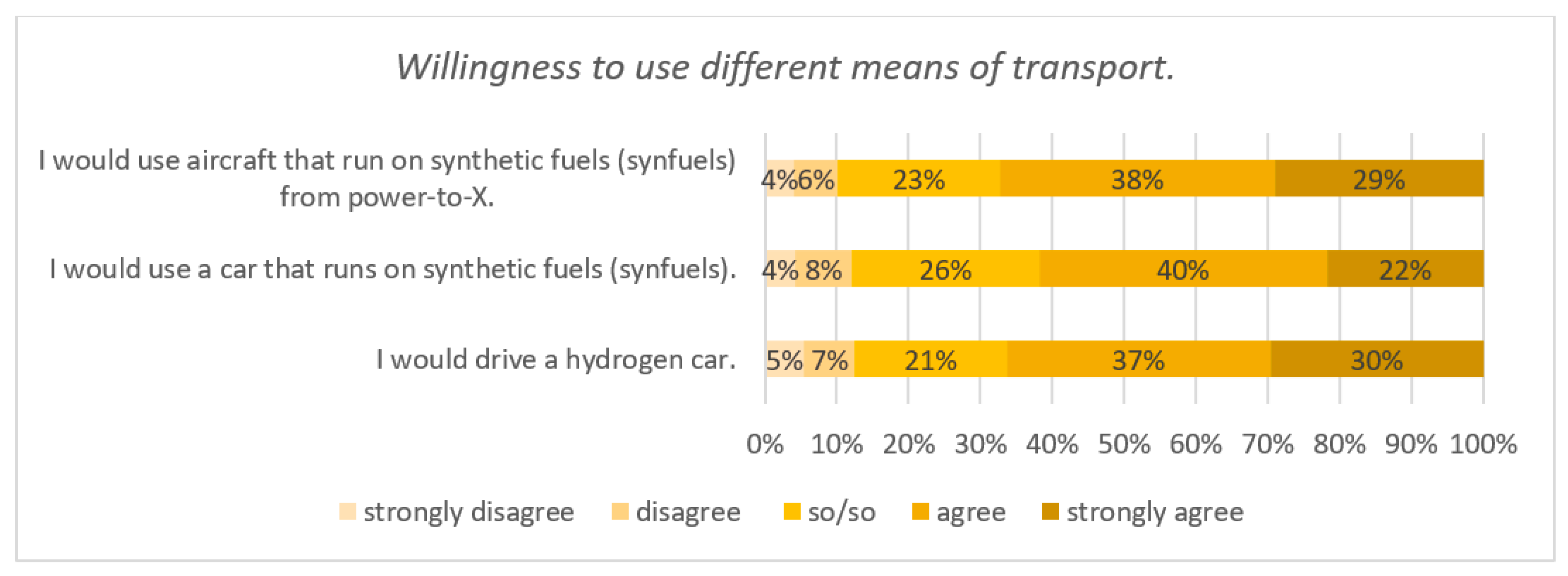

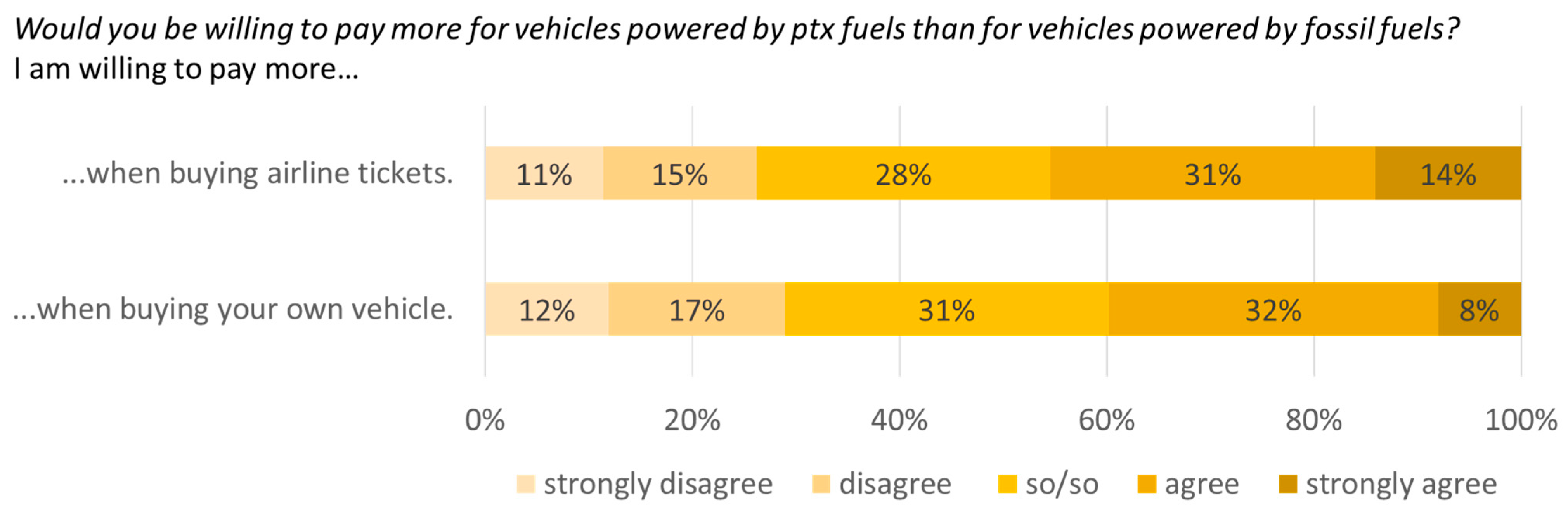

3.2. Level of Acceptance of PtX and Associative Perceptions

3.3. Conditional Acceptance of PtX

- “Green” hydrogen (i.e., hydrogen produced by using renewable energy sources) clearly received the highest level of acceptance here (mean value M = 4.29 for the youth sample and M = 4.39 for the adult sample on a scale of 1 = “do not agree at all” to 5 = “agree completely”; significant difference: t = −2.52, df = 2064, p < 0.05).

- Fossil fuels (youth sample: M = 2.27; adult sample: M = 2.39; significant difference: t = −2.21, df = 2021, p < 0.05) received low agreement, even in the case where the CO2 emissions were captured (youth sample: M = 2.84; adult sample: M = 2.93; difference was not significant: t = −1.671, df = 1936, p > 0.05). Thus, most agreement values of the youth were significantly lower.

- Only water that is not lacking elsewhere should be used (youth sample: M = 4.30; adult sample: M = 4.48; significant difference: t = −4.91, df = 2112, p < 0.001).

- Water is sufficiently available on site (youth sample: M = 4.25; adult sample: M = 4.45; significant difference: t = −5.57, df = 2100, p < 0.001).

- Compared to the two options above, the option “Water should be used from where it is cheapest” received lower agreement values (youth sample: M = 2.71; adult sample: M = 3.31; significant difference: t = −11.71, df = 2018, p < 0.001). Thus, again, the adults’ consent scores are significantly higher with respect to all options.

- Direct air capture (youth sample: M = 3.787; adult sample: M = 3.936; significant difference: t = −3.47, df = 1745, p < 0.001).

- Capture in industrial processes (youth sample: M = 4.02; adult sample: M = 4.18; significant difference: t = −3.94, df = 1982, p < 0.001). Here, too, the same picture emerged when comparing young people and adults: the adults’ approval ratings were significantly higher.

3.4. Influencing Factors of the General Acceptance of PtX Technologies

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.1.1. Current Level of Public Knowledge Regarding PtX

4.1.2. Public Acceptance of PtX: General Level, Factors, and Conditional Acceptance

4.1.3. Differences Between Youth and Adult Samples

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CCS | Carbon capture and storage |

| CCU | Carbon capture and utilization |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| M | Mean value |

| N | Sample size |

| PtX | Power-to-X |

| SD | Standard deviation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Scale | Item in German | Item in English | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior knowledge | Ich würde mein Vorwissen zum Thema Power-to-X wie folgt einordnen. | I would categorize my prior knowledge on the subject of power-to-x as follows: | ||

| General acceptance of power-to-x technologies | Grundsätzlich bin ich gegen Power-to-X-Technologien in Deutschland. | In principle, I am against power-to-x technologies in Germany. | ||

| Grundsätzlich lehne ich Power-to-X-Technologien ab. | In principle, I reject power-to-x technologies. | |||

| Prinzipiell bin ich ein *e Befürworter *in von Power-to-X-Technologien. | In principle, I am a supporter of power-to-x technologies. | |||

| Alles in allem unterstütze ich die Nutzung von Power-to-X-Technologien in Deutschland. | All in all, I support the use of power-to-x technologies in Germany. | |||

| Acceptance transport sector | Alles in allem unterstütze ich die Nutzung von Power-to-X-Technologien im Verkehrssektor in Deutschland. | All in all, I support the use of power-to-x technologies in the transport sector in Germany. | ||

| Acceptance industrial/energy sector | Alles in allem unterstütze ich die Nutzung von Power-to-X-Technologien im Energiesektor in Deutschland. | All in all, I support the use of power-to-x technologies in the energy sector in Germany. | ||

| Acceptance chemical sector | Alles in allem unterstütze ich die Nutzung von Power-to-X-Technologien im Chemiesektor in Deutschland. | All in all, I support the use of power-to-x technologies in the chemical sector in Germany. | ||

| Ecological impact of power-to-x technologies | Im Allgemeinen entlastet die Nutzung von Power-to-X-Technologien die Umwelt. | In general, the use of power-to-x technologies relieves the environment. | ||

| Power-to-X-Technologien tragen zum Kampf gegen den Klimawandel bei. | Power-to-x technologies contribute to the fight against climate change. | |||

| Power-to-X-Technologien tragen dazu bei, fossile Ressourcen wie Mineralöl und Erdgas einzusparen. | Power-to-x technologies help to save fossil resources such as mineral oil and natural gas. | |||

| Power-to-X-Technologien tragen zur Verringerung der CO2-Emissionen bei. | Power-to-x technologies help reduce CO2 emissions. | |||

| Power-to-X-Technologien tragen dazu bei, die Abhängigkeit von fossilen Ressourcen und deren Kosten zu reduzieren. | Power-to-x technologies help reduce dependence on fossil resources and their costs. | |||

| Fair value creation | Die Nutzung von Power-to-X wird sich positiv auf Deutschland als Wirtschaftsstandort auswirken. | The use of power-to-x will have a positive impact on Germany as a business location. | ||

| Die Nutzung von Power-to-X wird einen positiven Beitrag zur Entwicklung von meiner Region leisten. | The use of power-to-x will make a positive contribution to the development of my region. | |||

| Von der Realisierung von Power-to-X werden am Schluss alle profitieren. | In the end, everyone will benefit from the realization of power-to-x. | |||

| Das Verhältnis von Kosten und Nutzen bei Power-to-X wird in Deutschland fair verteilt sein. | The cost-benefit ratio for power-to-x will be fairly distributed in Germany. | |||

| Environmental awareness | Ich glaube, die Umweltprobleme werden immer gravierender. | I think environmental problems are becoming more and more serious. | ||

| Ich denke, der Mensch sollte in Harmonie mit der Natur leben, um eine nachhaltige Entwicklung zu erreichen. | I think human beings should live in harmony with nature to achieve sustainable development. | |||

| Ich glaube, wir tun nicht genug, um die knappen natürlichen Ressourcen vor der Übernutzung zu bewahren. | I think we are not doing enough to save scarce natural resource from being used up. | |||

| Ich denke, der Einzelne trägt Verantwortung für den Umweltschutz. | I think individuals have the responsibility to protect the environment. | |||

| Personal innovativeness | Wenn ich von innovativen Produkten und Technologien höre, suche ich nach Möglichkeiten, diese auszuprobieren. | When I hear about innovative products and technologies, I look for ways to try them out. | ||

| In meinem Umfeld gehöre ich zu den ersten, der/die die neuen Produkte und Technologien ausprobiert. | Among my colleagues, I am one of the first to try out new products and technologies. | |||

| Im Allgemeinen scheue ich mich davor, innovative Produkte und Technologien auszuprobieren. (Excluded as described in the method section) | In general, I am reluctant to try out innovative products and technologies. (Excluded as described in the method section) | |||

| Ich experimentiere gerne mit innovativen Produkten und Technologien. | I like to experiment with innovative products and technologies. | |||

| Social norm | Die meisten Menschen, die mir wichtig sind, sind der Meinung, dass ich nachhaltige Produkte kaufen sollte. | Most people who are important to me think I should buy sustainable products. | ||

| Wenn ich ein nachhaltiges Produkt kaufe, möchte ich das tun, was für mich wichtige Menschen von mir erwarten. | When buying a sustainable product, I wish to do what people who are important to me want me to do. | |||

| Wenn ich ein nachhaltiges Produkt kaufe, dann würden die meisten Menschen, die mir wichtig sind, auch ein nachhaltiges Produkt kaufen. | If I buy a sustainable product, then most people who are important to me would also buy a sustainable product. | |||

| Menschen, deren Meinung ich schätze, würden es vorziehen, dass ich ein nachhaltiges Produkt kaufe. | People whose opinions I value would prefer that I buy a sustainable product. | |||

| An welche Personen hast du bei der Beantwortung der letzten Fragen gedacht? (offene Frage) | What people did you think of when answering the last questions? | |||

| Personal norm | Aufgrund meiner eigenen Prinzipien fühle ich mich verpflichtet, ein nachhaltiges Produkt zur Reduzierung der Kohlenstoffemissionen zu kaufen. | Because of my own principles I feel an obligation to purchase a sustainable product to reduce carbon emissions. | ||

| Wenn ich ein Produkt kaufe, fühle ich mich moralisch verpflichtet, ein nachhaltiges Produkt zu kaufen, unabhängig davon, was andere Menschen tun. | If I buy a product, I feel morally obligated to buy a sustainable product, regardless of what other people do. | |||

| Ich fühle mich verpflichtet, bei Kaufentscheidungen die Umweltfolgen der Produkte zu berücksichtigen. | I feel obligated to take the environmental consequences of products into account when making purchasing choices. | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | Wie viel Kontrolle hast Du darüber, inwiefern Du Dich nachhaltig verhältst? | How much control do you have over how you behave in a sustainable way? | ||

| Für mich ist nachhaltiges Verhalten... | For me, sustainable behavior is... | |||

| Wie schwierig ist es für Dich, Dich nachhaltig zu verhalten? | How difficult is it for you to behave sustainably? | |||

| Conditional acceptance | Wasserstoff ist ein zentraler Grundstoff im Power-to-X-Prozess. Welche Energiequellen sollen genutzt werden, um den Wasserstoff zu erzeugen? | Hydrogen is a central basic material in the power-to-x process. Which energy sources should be used to generate the hydrogen? | ||

| Erneuerbare Energien (z. B. Wind, Sonne). | Renewable energies (e.g., wind, solar). | |||

| Fossile Brennstoffe (z. B. Kohle, Erdöl), das dabei entstehende CO2 (Kohlenstoffdioxid) entweicht in die Atmosphäre. | Fossil fuels (e.g., coal, petroleum), the resulting CO2 (carbon dioxide) escapes into the atmosphere. | |||

| Fossile Brennstoffe, das dabei entstehende CO2 wird abgeschieden und gespeichert. | Fossil fuels, the resulting CO2 is captured and stored. | |||

| Durch die Spaltung von Methan unter hohen Temperaturen, sog. Methanpyrolyse. | By splitting methane under high temperatures, so-called methane pyrolysis. | |||

| Wasserstoff wird aus Wasser gewonnen. Woher soll das benötigte Wasser im Power-to-X-Prozess stammen? | Hydrogen is obtained from water. Where should the water needed in the power-to-x process come from? | |||

| Das verwendete Wasser soll nicht an anderer Stelle (z. B. als Trinkwasser) fehlen. | The water used should not be lacking elsewhere (e.g., as drinking water). | |||

| Das verwendete Wasser sollte an dem Ort, wo es benötigt wird, in ausreichender Menge vorhanden sein. | The water used should be available in sufficient quantity at the place where it is needed. | |||

| Es sollte Wasser von dort genutzt werden, wo es am billigsten ist. | Water should be used from where it is cheapest. | |||

| Als nächstes wird in der Prozesskette für die Umwandlung des Wasserstoffs in andere Stoffe Kohlenstoff benötigt. Wie soll dieser Kohlenstoff gewonnen werden? | Next, carbon is needed in the process chain for the conversion of hydrogen into other substances. How is this carbon to be obtained? | |||

| Der dafür benötigte Kohlenstoff soll direkt aus der Luft entnommen werden (sogenanntes Direct Air Capture). | The carbon required for this is to be taken directly from the air (so-called direct air capture). | |||

| Es sollte Kohlenstoff verwendet werden, der in der Industrie als Abfallprodukt anfällt. | Carbon should be used, which is a waste product in industry. | |||

| Semantic differential | Welche Attribute verbindest du mit Power-to-X? | What attributes do you associate with power-to-x? | ||

| umweltbelastend | umweltschonend | environmentally harmful | environmentally friendly | |

| Innovativ | rückständig | innovative | backward | |

| Wirtschaftlich | unwirtschaftlich | economical | uneconomical | |

| flächenschonend | flächenintensiv | space-saving | land intensive | |

| sauber | dreckig | clean | dirty | |

| gesundheitsschädlich | gesundheitsförderlich | harmful to health | beneficial to healthy | |

| wettbewerbsfähig | nicht wettbewerbsfähig | competitive | not competitive | |

| national | international | national | international | |

| gefährlich | ungefährlich | dangerous | harmless | |

| zuverlässig | unzuverlässig | reliable | unreliable | |

| sicher | unsicher | safe | unsafe | |

| sinnvoll | nicht sinnvoll | Reasonable | not useful | |

References

- Schnuelle, C.; Thoeming, J.; Wassermann, T.; Thier, P.; von Gleich, A.; Goessling-Reisemann, S. Socio-technical-economic assessment of power-to-X: Potentials and limitations for an integration into the German energy system. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausfelder, F.; Dura, H.E.; Bareiß, K.; Schönleber, K.; Hamacher, T. (Eds.) Roadmap des Kopernikus-Projektes “Power-to-X”: Flexible Nutzung erneuerbarer Ressourcen (P2X) [Roadmap of the Kopernikus Project “Power-to-X”: Flexible use of Renewable Resources (P2X)]; Lehrstuhl für Erneuerbare und Nachhaltige Energiesysteme: Frankfurt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, I.; Schweizer-Ries, P.; Hildebrand, J. Participation Strategies—the Silver Bullet for Public Acceptance? In Vulnerability, Risk and Complexity: Impacts of Global Change on Human Habitats; Kabisch, S., Kunath, A., Schweizer-Ries, P., Steinführer, A., Eds.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2012; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Roddis, P.; Carver, S.; Dallimer, M.; Norman, P.; Ziv, G. The role of community acceptance in planning outcomes for onshore wind and solar farms: An energy justice analysis. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vögele, S.; Rübbelke, D.; Mayer, P.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Germany’s “No” to carbon capture and storage: Just a question of lacking acceptance? Appl. Energy 2018, 214, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Oltra, C.; Boso, À. Towards a cross-paradigmatic framework of the social acceptance of energy systems. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.; Molin, E.J.; Steg, L. Psychological factors influencing sustainable energy technology acceptance: A review-based comprehensive framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Innovation: An Introduction to the Concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emodi, N.V.; Lovell, H.; Levitt, C.; Franklin, E. A systematic literature review of societal acceptance and stakeholders’ perception of hydrogen technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 30669–30697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönauer, A.-L.; Glanz, S. Hydrogen in future energy systems: Social acceptance of the technology and its large-scale infrastructure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 12251–12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häußermann, J.J.; Maier, M.J.; Kirsch, T.C.; Kaiser, S.; Schraudner, M. Social acceptance of green hydrogen in Germany: Building trust through responsible innovation. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos-Romero, A.; Cordoves-Sánchez, M.; Cisternas, C.; Sáez-Ardura, F.; Rodríguez, I.; Aledo, A.; Boso, Á.; Prades, J.; Álvarez, B. Green Hydrogen and Social Sciences: Issues, Problems, and Future Challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.A.; de Vries, G.; Molin, E.J. A positive Shift in the Public Acceptability of a Low-Carbon Energy Project After Implementation: The Case of a Hydrogen Fuel Station. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovell, M.D. Explaining hydrogen energy technology acceptance: A critical review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 10441–10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. A normative decision-making model of altruism. In Altruism and Helping Behavior: Social, Personality and Developmental Perspective; Rushton, J.P., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. Contextual and Psychological Factors Shaping Evaluations and Acceptability of Energy Alternatives: Integrated Review and Research Agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, D.; Demski, C.; Becker, S.; Pidgeon, N. The relationship between justice and acceptance of energy transition costs in the UK. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft, M.B.; Schuitema, G.; Thøgersen, J. Responsible technology acceptance: Model development and application to consumer acceptance of Smart Grid technology. Appl. Energy 2014, 134, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Rethinking Nimbyism: The Role of Place Attachment and Place Identity in Explaining Place-Protective Action. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaka, B.; Lindberg, K.; Kienast, F.; Hunziker, M. How landscape-technology fit affects public evaluations of renewable energy infrastructure scenarios. A hybrid choice model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovation: A Cross-Cultural Approach; The Free Press: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrenkind, B.; Brendel, A.B.; Nastjuk, I.; Greve, M.; Kolbe, L.M. Investigating end-user acceptance of autonomous electric buses to accelerate diffusion. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 74, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heek, J.; Arning, K.; Ziefle, M. Differences between laypersons and experts in perceptions and acceptance of CO2-utilization for plastics production. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 7212–7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arning, K.; Offermann-van Heek, J.; Ziefle, M. What drives public acceptance of sustainable CO2-derived building materials? A conjoint-analysis of eco-benefits vs. health concerns. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Quenzel, Q. Jugend 2019-18. Shell Jugendstudie: Eine Generation Meldet Sich Zu Wort [Shell Youth Study: A Generation Speaks Out]; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, J.; Bellmann, E. Invisible Kids: Eine Akzeptanzuntersuchung Zu Power-to-X-Technologien Bei Jugendlichen [Invisible Kids: An Acceptance Study on Power-to-X Technologies among Young People]. In Akzeptanz Und Politische Partizipation in Der Energietransformation; Fraune, C., Knodt, M., Gölz, S., Langer, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 323–351. [Google Scholar]

- BMU; UBA. Zukunft? Jugend fragen! Umwelt, Klima, Politik, Engagement—Was Junge Menschen Bewegt [Future? Ask Youth! Environment, Climate, Politics, Commitment—What Moves Young People]; Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit und Umweltbundesamt Bundesministerium für Umwelt: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). Definition of Youth. 2013. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Kortsch, T.; Hildebrand, J.; Schweizer-Ries, P. Acceptance of Biomass Plants–Results of a Longitudinal Study in the Bioenergy-Region Altmark. Renew. Energy 2015, 83, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arning, K.; van Heek, J.; Ziefle, M. Acceptance Profiles for a Carbon-Derived Foam Mattress. Exploring and Segmenting Consumer Perceptions of a Carbon Capture and Utilization Product. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: Using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Terry, D.J.; Masser, B.M.; Hogg, M. A Integrating social identity theory and the theory of planned behaviour to explain decisions to engage in sustainable agricultural practices. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Linzenich, A.; Arning, K.; Offermann-van Heek, J.; Ziefle, M. Uncovering attitudes towards carbon capture storage and utilization technologies in Germany: Insights into affective-cognitive evaluations of benefits and risks. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 48, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An r package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawilowsky, S.S.; Blair, R.C. A more realistic look at the robustness and type II error properties of the t test to departures from population normality. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Razavi, P.; Karakislak, I.; Hildebrand, J. German Media Discourses and Public Perceptions on Hydrogen Imports: An Energy Justice Perspective. Energy Technol. 2024, 2301000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) National Hydrogen Strategy Update—NHS 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Hydrogen/Downloads/national-hydrogen-strategy-update.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Kortsch, T.; Händeler, P. Explaining sustainable purchase behavior in online flight booking—Combining value-belief-norm model and theory of planned behavior. Gr. Interakt. Org. 2024, 55, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tan, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Gao, W. Willingness of Chinese households to pay extra for hydrogen-fuelled buses: A survey based on willingness to pay. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1109234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhao, J. Willingness to pay for heavy-duty hydrogen fuel cell trucks and factors affecting the purchase choices in China. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 24619–24634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.; Powalla, O.; Kortsch, T.; Rau, I. Strombasierte Flugtreibstoffe aus erneuerbaren Energien als Baustein einer nachhaltigen Luftfahrt? [Electricity-based aviation fuels from renewable energy sources as a building block of sustainable aviation?]. Energ. Tagesfr. 2021, 71, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, G. How positive framing may fuel opposition to low-carbon technologies: The boomerang model. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 36, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, G. Public communication as a tool to implement environmental policies. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2020, 14, 244–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaunbrecher, B.S.; Bexten, T.; Wirsum, M.; Ziefle, M. What is Stored, Why, and How? Mental Models, Knowledge, and Public Acceptance of Hydrogen Storage. Energy Proced. 2016, 99, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arning, K.; Offermann, J.; Engelmann, L.; Gimpel, R.; Ziefle, M. Between financial, environmental and health concerns: The role of risk perceptions in modeling efuel acceptance. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1519184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.; Sadat-Razavi, P.; Rau, I. Different Risks—Different Views: How Hydrogen Infrastructure is Linked to Societal Risk Perception. Energy Technol. 2024, 2300998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, H.L.; Skiple, J.K.; Gregersen, T.; Derempouka, E.; Skjold, T. In the green? Perceptions of hydrogen production methods among the Norwegian public. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 97, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBA (Ed.) 25 Jahre Umweltbewusstseinsforschung im Umweltressort. Langfristige Entwicklungen und aktuelle Ergebnisse [25 Years of Environmental Awareness Research in the Department of the Environment. Long-Term Developments and Current Results]. Dessau-Roßlau. 2021; Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/5750/publikationen/2021_hgp_umweltbewusstseinsstudie_bf.pdf. (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Langer, K.; Decker, T.; Roosen, J.; Menrad, K. A qualitative analysis to understand the acceptance of wind energy in Bavaria. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hienuki, S.; Hirayama, Y.; Shibutani, T.; Sakamoto, J.; Nakayama, J.; Miyake, A. How Knowledge about or Experience with Hydrogen Fueling Stations Improves Their Public Acceptance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovell, M.D.; Walton, A. Identifying informed beliefs about hydrogen technologies across the energy supply chain. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 31825–31836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.; Peterson, N. Motivating Action through Fostering Climate Change Hope and Concern and Avoiding Despair among Adolescents. Sustainability 2016, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, F.; Stede, J. The EU sustainable finance taxonomy and its contribution to climate neutrality. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2021, 14, 128–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PtX-Hub. PtX.Sustainability—Dimensions and Concerns. Towards a Conceptual Framework for Standards and Certification. 2021. Available online: https://ptx-hub.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/PtX-Hub-PtX.Sustainability-Dimensions-and-Concerns-Scoping-Paper.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2024).

| Youth Sample | Adult Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 1123 | 1134 |

| Age [Years] | ||

| M | 21.53 | 51.84 |

| SD | 2.51 | 14.91 |

| Range | 16–25 | 26–87 |

| Gender [%] | ||

| Male | 38.74 | 47.88 |

| Female | 60.91 | 51.85 |

| Diverse/non-binary | 0.36 | 0.27 |

| Scale (No. of Items) | Youth Sample | Adult Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha | M | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

| Prior knowledge (1) | 1.44 | 0.74 | - a | 1.35 | 0.69 | - a |

| Public acceptance of ptx technologies (4) | 3.85 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 3.87 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| Ecological impact of ptx technologies (5) | 3.85 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 3.90 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| Fair value creation (4) | 3.63 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 3.69 | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| Environmental awareness (4) | 4.18 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 4.24 | 0.72 | 0.82 |

| Personal innovativeness (3) | 3.13 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 2.94 | 0.74 | 0.87 |

| Social norm (4) | 3.18 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 2.99 | 1.01 | 0.89 |

| Personal norm (3) | 3.56 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 3.45 | 1.02 | 0.93 |

| Perceived behavioral control (3) | 3.34 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 3.36 | 0.73 | 0.77 |

| Sectoral PtX Acceptance | Total Sample | Youth Sample | Adult Sample | Group Comparisons (Youth vs. Adult) 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p | |

| General | 3.86 | 0.77 | 3.85 | 0.73 | 3.87 | 0.80 | −0.83 | 2008 | 0.405 |

| Mobility sector | 3.93 | 0.86 | 3.89 | 0.85 | 3.98 | 0.88 | −2.25 | 1990 | 0.024 |

| Industry sector | 3.97 | 0.86 | 3.93 | 0.83 | 4.01 | 0.88 | −2.05 | 2007 | 0.041 |

| Chemistry | 3.89 | 0.92 | 3.82 | 0.93 | 3.98 | 0.90 | −3.88 | 1881 | <0.001 |

| Predictor | Total Sample | Youth Sample | Adult Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior knowledge | −0.07 *** | −0.11 *** | −0.04 n.s. |

| Ecological impact | 0.51 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.54 *** |

| Fair value creation | 0.13 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.15 *** |

| Environmental awareness | 0.10 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.04 n.s. |

| Personal innovativeness | 0.08 *** | −0.04 n.s. | 0.11 ** |

| Social norm | −0.13 *** | −0.06 n.s. | −0.19 *** |

| Personal norm | −0.03 n.s. | −0.02 n.s. | −0.03 n.s. |

| Perceived behavioral control | −0.05 * | −0.09 ** | −0.02 n.s. |

| Age | −0.01 n.s. | 0.01 n.s. | 0.02 n.s. |

| Gender 1,2 | 0.07 *** | 0.05 n.s. | 0.10 *** |

| R2 | 41.1% | 39.4% | 44.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hildebrand, J.; Kortsch, T.; Rau, I. The Public Acceptance of Power-to-X Technologies—Results from Environmental–Psychological Research Using a Representative German Sample. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6574. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146574

Hildebrand J, Kortsch T, Rau I. The Public Acceptance of Power-to-X Technologies—Results from Environmental–Psychological Research Using a Representative German Sample. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6574. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146574

Chicago/Turabian StyleHildebrand, Jan, Timo Kortsch, and Irina Rau. 2025. "The Public Acceptance of Power-to-X Technologies—Results from Environmental–Psychological Research Using a Representative German Sample" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6574. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146574

APA StyleHildebrand, J., Kortsch, T., & Rau, I. (2025). The Public Acceptance of Power-to-X Technologies—Results from Environmental–Psychological Research Using a Representative German Sample. Sustainability, 17(14), 6574. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146574