1. Introduction

The escalating global climate and ecological crisis necessitates innovative approaches to holistically sustainable urban living [

1]. Food production, traditionally associated with rural areas, is increasingly recognised as a crucial component of resilient cities [

2]. With the increasing impact of climate change on global food systems, cities must also adapt to ensure food security [

3]. One such adaptation is urban food growing (commonly known as urban agriculture in the literature), which involves cultivating food within urban spaces. As urban populations continue to rise, integrating food production into cityscapes becomes more essential for addressing this interplay between food security, climate change, and biodiversity loss.

Urban food growing initiatives help build resilience to a range of socio-economic and environmental pressures by improving food security and public health while building social capital, and promoting circular economy principles [

4]. Urban food growing can be defined as food production in residential gardens or plots in urban or peri-urban areas including growing edible plants and crops, and rearing animals [

5]. It offers numerous advantages, including improved health outcomes, mental well-being, ecosystem benefits, and enhanced social interactions [

4]. It also promotes biodiversity, encourages pro-environmental behaviours, and reduces food miles, thus lowering carbon footprints [

6]. Socially, urban food growing initiatives foster community cohesion by bringing people together and encouraging collective action towards shared goals [

7].

In various historical and geographically diverse contexts, community growing is characterised by practices deeply rooted in cultural traditions, such as community orchards, community farms, and shared gardens [

8]. They served as vital conduits for transmitting indigenous knowledge, reinforcing social cohesion, and embodying spiritual connections to the land leading to environmental protection. For example, the communal management of medicinal herb gardens in some African communities, as documented by Niñez (1987) [

9], preserved traditional healing practices and facilitated intergenerational knowledge exchange. Similarly, the multi-strata home gardens of Southeast Asia often cultivated plants with symbolic significance, integrating cultural beliefs into daily practices [

10]. In the Andean region, the communal labour required for terrace farming, as noted by Altieri and Toledo (2011) [

11] in their discussions of Latin American agroecology, reinforced social bonds and reflected a collective understanding of sustainable land management. These examples underscore the historical role of community food growing, amongst places where people live and work, as a cultural cornerstone, weaving together ecological, social, and cultural dimensions of community life while also providing additional benefits of nutritional value and improved physical and mental health. Despite their diverse forms and contexts, these initiatives share the goal of empowering communities to take ownership of their food systems, leading to healthier urban environments.

Contemporary urban settings in the UK see these initiatives manifest in different forms, including allotments, city farms, rooftop gardens, and terrace farming. The Friends of the Earth (2020) [

12] report demonstrates that investing £5.5 billion in improving adequate green infrastructure could yield a £200 billion benefit in physical health and well-being. This is further evidenced by research carried out by the Institute for Sustainable Food at the University of Sheffield, 2020 [

13], which found that converting 10% of a city’s green spaces into fruit and vegetable patches could supply 15% of the local population with their ‘five a day’. Consequently, community growing initiatives have gained prominence as a sustainable solution for enhancing food security, improving public health, and fostering community cohesion [

14]. In the UK, such allotments pose certain drawbacks, including cost, waiting lists, and restrictions, making them less accessible to some urban residents, particularly those in low-income communities [

15]. Projects such as Incredible Edible Todmorden [

16] have demonstrated the potential of using public spaces for growing food, fostering local pride, and encouraging community involvement. Similarly, Lambeth’s Eat Off Your Street campaign [

17] introduced edible garden carts into unused urban spaces, promoting community cohesion and informal food sharing. While these models have been successful in raising awareness and promoting food growing in urban areas, they are more often implemented by volunteer groups who do not necessarily live on the streets where the initiatives are based.

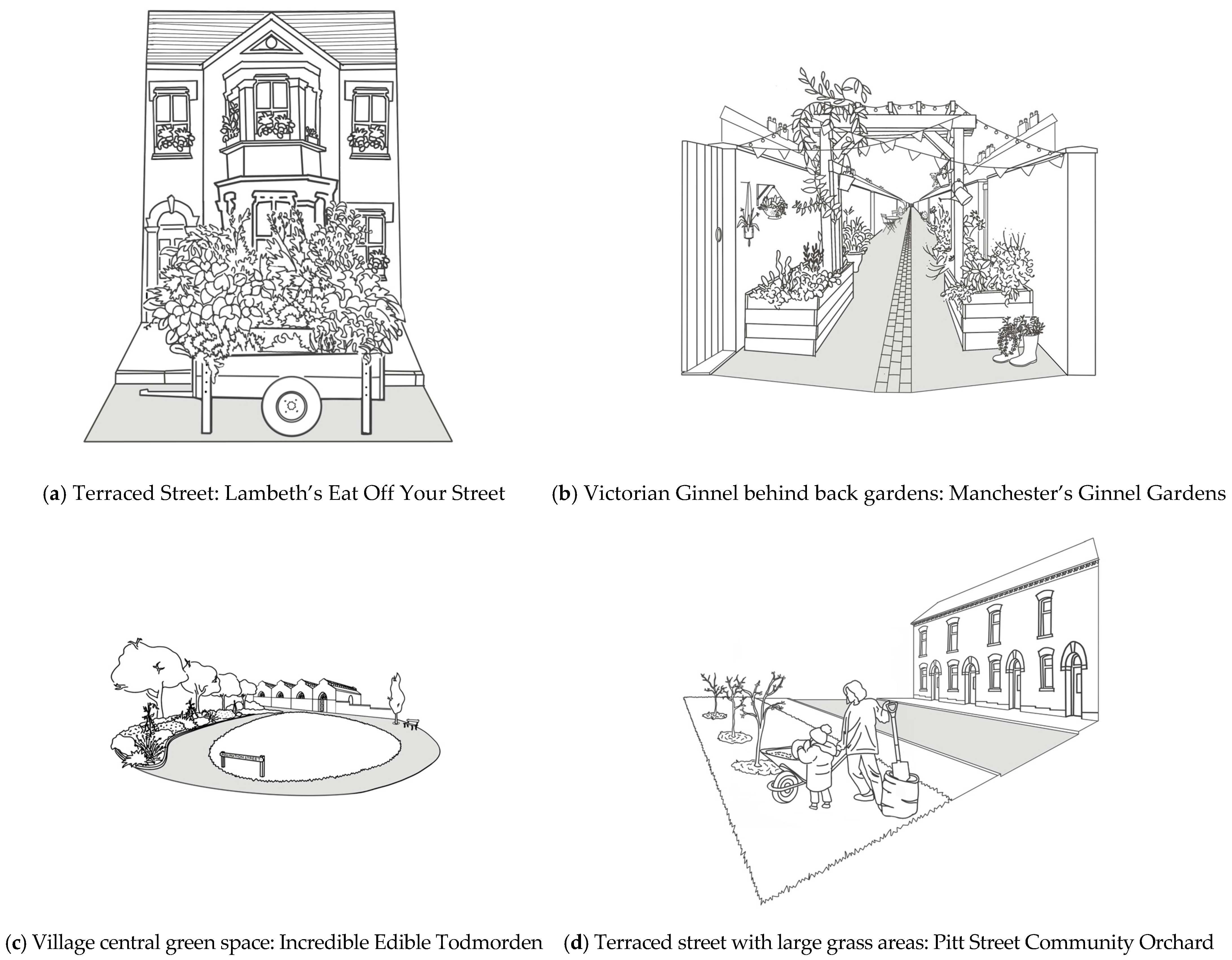

Figure 1 below highlights some examples of types of spaces in different street types, based on precedents, that could be Edible Streets.

This study introduces the concept of “Edible Streets” that addresses these challenges by embedding food production into everyday urban environments, enhancing visibility, accessibility, and local participation. It is an inclusive form of community food growing, where people who live/work on a street would grow food together. Defined as a mechanism to integrate community food production on publicly owned and publicly accessible land on streets by using underused urban areas bordering urban streets. The edible plants are visible to anyone walking in the street and are easy to access by occupants of the street for maintenance and harvesting—making it easier to participate in food production. The hypothesis is that Edible Streets can not only overcome the limitations of existing community food-growing models but also enhance community engagement.

The Broken Plate Report, 2021 [

19] highlights that people living in more deprived local areas have easy and increased access to unhealthy food in their neighbourhood and limited access to fresh, highly nutritious food. These deprived areas are defined as ‘food deserts’ [

20]. Enabling an improved sense of security in local food growing, tackles the UK’s heavy reliance on international food supply chains [

21]. Whilst Oxford doesn’t fall under the ‘food desert’ category, some parts of the city still present a matter of concern [

22]. According to the Indices of Deprivation [

23], 29% of children in Oxford are living below the poverty line with a nutritionally inadequate diet, characterised by a limited intake of fruits and vegetables. Research shows that children’s diets can be improved by being involved in growing and cooking food [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Yet, this remains inaccessible to some due to a lack of green infrastructure, resulting in a greater reliance on imported, processed foods. Further, over 21% of Oxford’s population is made up of university students [

28]. Their transient existence in a place means a lack of willingness to engage in local community projects on an individual level, especially food growing, as they finish their studies and leave the city, just when it is harvesting season. At the same time, emerging evidence confirms that university students are acquiring poor-quality diets [

29]. This study contributes to the existing knowledge by exploring how public street spaces in the UK can be transformed into accessible food-growing environments for people who live/work there. This can address food insecurity and seamlessly include growing activities into everyday life. Unlike traditional community gardens or allotments, Edible Streets support the repurposing, by the local community, of underutilised public spaces along frequently travelled paths, increasing visibility and inclusivity.

Barton in Oxfordshire was selected as the site for the Edible Streets study due to several factors that reflect the need for accessible, community-driven food-growing initiatives, particularly in urban, deprived areas. A report on food poverty in Oxfordshire highlighted Barton as one of the two most deprived areas in Oxford with limited access to fresh vegetables and fruits [

30]. By introducing the Edible Streets project in Barton, underused green spaces, such as grass verges and alleyways, can be transformed into accessible growing spaces that the entire community can interact with daily and learn from each other. Therefore, Barton represents an ideal testbed for the Edible Streets study in Oxford, offering an opportunity to create a model for urban food growing that addresses food accessibility, promotes health and well-being, and fosters social cohesion in a way that is feasible for deprived urban communities. One of the main results of the Edible Streets study was to develop a “How-to” guide [

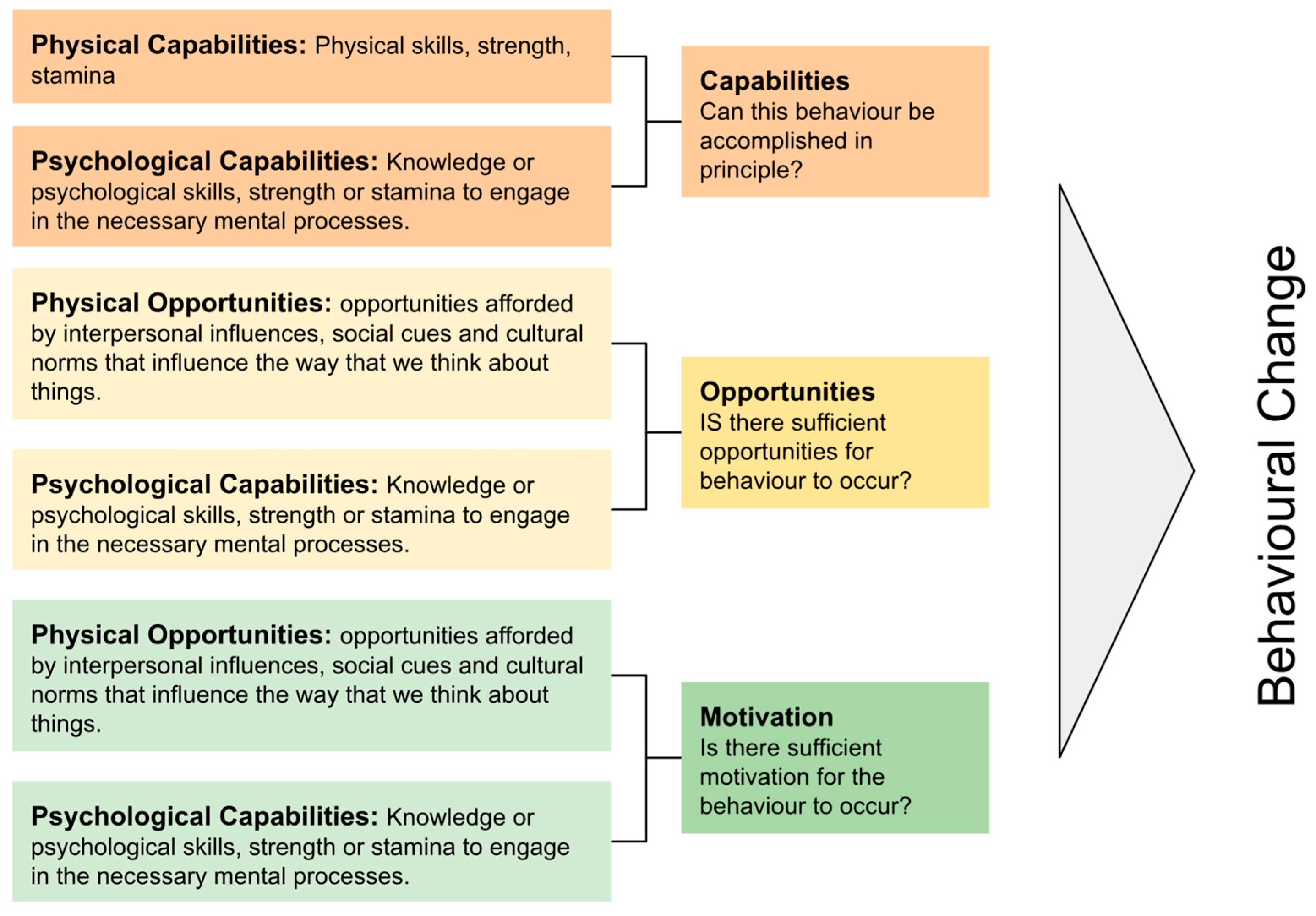

18] to help communities implement Edible Street initiatives within their residential areas. The present study identified key target groups (stakeholders) within the community that are most likely to benefit from or contribute to Edible Streets projects. The main aim of this paper is to gain an understanding of the target population’s drivers and barriers (using the COM-B model of behaviour change (capabilities, opportunities, and motivations)) [

31,

32] regarding food growing in public urban spaces in streets. The COM-B model offers a structured and evidence-based framework to explore factors influencing behaviour, making it particularly suitable for understanding how and why residents engage with public urban spaces and community-based food production. In the urban good-growing literature, COM-B has been used by Samangooei to understand the motivations of barriers for individuals to cultivate edible plants on buildings [

32]. By assessing the primary drivers for community interest, the study aimed to uncover the factors that inspire residents to participate in Edible Streets projects. Additionally, it evaluated the barriers that may hinder the implementation of these initiatives.

This research makes key contributions to the field of regenerative urban development and community food systems by presenting Edible Streets as a novel approach to urban greening, emphasising inclusive, street-level food growing led by residents who live/work in the street. It applies the COM-B Behaviour Change Model to analyse the capabilities, opportunities, and motivations influencing community engagement in food growing, offering new behavioural insight in this context. The study advances both conceptual understanding and practical implementation strategies for community-led urban growing within the broader sustainability agenda.

3. Results

Participants were numbered from 1 to 35 and the stakeholder groups were numbered from 1 to 3 (

Table 4).

The participants in this study ranged in age from 18 to 90 years old, with the most represented age group being 36–55 years, comprising 38.7% of respondents. This was followed by the 65–75 age group (19.4%), and both the 50–60 and 56–65 groups at 12.9% each. Smaller proportions were noted in the 18–25, 26–35, 60–70, and 80–90 brackets, reflecting a skew towards middle-aged and older adults. In terms of gender, the majority of respondents were female (77.4%), while 16.1% were male, and 3.2% identified as non-binary. One participant did not report their gender. Most participants lived in Barton (48.4%), followed by Marston (35.5%), with smaller groups residing in Headington (6.5%), Northway (6.5%), Cowley/Blackbird Leys (3.2%), and Burlipton (3.2%). This indicates a strong concentration of responses from Barton and Marston, two areas with distinct community profiles within Oxford. The majority of respondents (71%) lived in semi-detached houses, with 16.1% living in terraced housing, 9.7% in flats, and 6.5% in detached houses. Some participants provided more specific classifications, such as “end of terrace”, which were grouped accordingly. Regarding outdoor space, 83.9% of participants reported having access to a private or community garden, while 16.1% did not. In terms of housing tenure, 51.6% of respondents owned their homes, and 48.4% were renters or lived in council housing.

According to the 2021 Census data, Barton shows a slightly higher proportion of residents in the older age brackets compared to the Oxford average [

36]. Conversely, the survey data presents a less representative picture of the broader Oxford population. The overwhelming female majority, comprising 89% of respondents, significantly deviates from the typically balanced gender distribution observed in the city and the UK as a whole, introducing a substantial gender bias. The age distribution, while capturing a segment of the working-age population, primarily those aged 36–55, under-represents younger and older demographics. According to the 2021 Census, Oxford has a relatively young population, with a significant student presence, which is not reflected in the survey sample [

36].

The data collected was initially organised into 47 codes that captured the various drivers and barriers highlighted by the participants (

Figure 4). In the first round, these codes were developed inductively from the data by the researcher (K.G.), allowing the themes to emerge naturally from participants’ responses. A second round of coding was then conducted using the COM-B Model as a deductive framework to review and verify the authenticity and relevance of the initial codes. This dual approach ensured both grounded insight and theoretical alignment. These codes were then categorised into capabilities, opportunities, and motivations based on the COM-B Model [

31]. The codes under each category of the COM-B Model provided insight into the drivers and barriers of the participants to the implementation of the Edible Streets project in their streets. Theme selection was based on relevance rather than frequency, reflecting the small sample size and the importance of capturing the full breadth of participant experiences. The thematic framework and coding decisions were reviewed by co-researchers (M.Se. and M.S.), who validated the alignment of codes and themes with the COM-B framework. These drivers and barriers were studied to strategise the future implications of the project, for example, the development of the How-to Guide and the application and licensing model. To ensure the validity of the analysis, triangulation was employed, cross-checking emerging themes across resident participants, stakeholders, and secondary research to confirm consistency and strengthen the credibility of the findings.

3.1. Drivers

3.1.1. Fostering a Sense of Belonging and Community (n = 25)

The data showed that a key driver behind creating Edible Streets is rooted in the potential to foster community bonds and enhance local engagement [

37,

38,

39]. Participants highlighted that such initiatives could significantly “build community relationships and hopefully improve the local area by (having) more people committed to a joint project” (Participant 34). Beyond the social benefits, “planting and growing builds resilience in the community”, (Participant 16); participants also highlight that engaging in these activities helps them develop skills and knowledge that contribute to their community’s ability to adapt and thrive.

Ideas around the different activities that could potentially accompany Edible Street projects like “have(ing) a kind of local place where people can take food from their gardens, and then it can either be free food there, or it can be a place to buy and sell food, (promoting) sharing within the community” (Participant 1), were discussed by the participants. This highlighted the need for activity-based public engagement. This not only “attracts more people that means more socialising” (Participant 11), but also empowers individuals by allowing them to grow fresh produce and share it with their neighbours, as highlighted by Participant 9: “…I’m growing it fresh, knowing that I’m growing it myself and I’m contributing to making more fresher foods (available) to the community and I can share (it) around with neighbours”. Such events would facilitate food sharing within the community, allowing residents to support each other. Group 2 also emphasised the importance of Edible Streets being a community-driven project, highlighting the contribution of such initiatives in bringing people together and creating networks thus improving the resilience within communities.

3.1.2. Healthy Lifestyle (n = 28)

One of the primary drivers is access to fresh produce. Growing food locally ensures that community members have access to fruits and vegetables that are fresher and more nutritious than those bought from stores as well as easily accessible, helping alleviate food deserts [

40]. Participant 8 highlighted the superior quality of homegrown produce, noting that “anything homegrown is better than not having any vegetables at all or what you buy in the shops”. This access to fresh produce can significantly enhance the nutritional intake of community members, promoting better health.

Another driver is the positive impact on mental and physical health. Gardening and growing food provide a form of exercise, which is beneficial for overall well-being. Participant 16 emphasised that “Exercise- some form of movement and activity- helps with mental health”. This physical activity, combined with the satisfaction of growing one’s own food, can reduce stress and improve overall mental health [

41]. Additionally, being outdoors and connecting with nature enhances overall well-being. Participant 26 noted the dual benefits of “enhancing well-being through growing plants for food together; enhancing well-being by being outdoors, in and with nature”. Participant 21 also emphasised the importance of “connecting people with nature and their space”, suggesting that such interactions can strengthen community bonds and personal well-being. Group 3 discussed the importance of growing food within communities promoting healthy eating habits, and spreading knowledge about food, especially within the younger demographic. The group highlighted how this could improve the relationship with food among children and youngsters.

3.1.3. Environmental Drivers (n = 16)

Participant 22 emphasised that such initiatives “could help people see that moving to nature positive and climate friendly cities can be beneficial in many ways” showcasing the potential for improved quality of life. Participant 1 also highlighted that growing food locally can “reduce food waste and reduce the transporting of food and wasting fuel”, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation. “Revitalising misused or degraded areas of the neighbourhood”, (Participant 30) can breathe new life into these spaces, making them more attractive, functional, and environmentally friendly. “It would be great if trees were planted along all residential streets even if it would mean that concrete would have to be dug up and parking spaces sacrificed” (Participant 31). These comments link with environmental psychology research showing that connecting with nature can increase pro-environmental behaviour [

42].

Edible Streets also foster community connections with nature. Participant 21 mentioned that “Connecting people with nature and their space would be lovely for children” providing them with opportunities to engage with nature and learn about food production. Participant 18 added, “Children could climb them (trees). This would also provide a play area as well since the local play equipment was removed”. This kind of connection with nature from a young age creates a sense of belonging and protectiveness towards the environment [

43].

Moreover, the introduction of this green infrastructure would support biodiversity and attract wildlife. Participant 11 highlighted how “grow(ing) in sections of lawn, shrubs and trees is good to attract wildlife like birds, foxes and bees” Participant 25 emphasised the importance of “residents being involved in creating green spaces, increasing green connectivity”, that supports wildlife without the use of harmful pesticides leading to a better connection between growing food and eating. Green infrastructure on residential streets “will attract pollinating insects as well. So, it is good for bees and bugs” (Participant 5). Group 1 from the stakeholder workshops also pointed out the value addition of the Edible Streets initiative towards local wildlife from having fruit or nut trees.

3.2. Barriers

3.2.1. Knowledge and Skill Gaps (n = 29)

Many participants expressed concerns about their own and others’ gaps in knowledge and skills related to gardening and food production. As Participant 17 noted, “It’s important to give people proper instruction on how to grow and what to do when it comes to gardening and growing, how long does it take to grow, types of plants, combinations of plants and seasonality of plants”. This indicates a need for education and guidance on the basics of growing food. During the workshops with other stakeholders, concerns regarding knowledge and understanding of sustainable practices, such as the use of natural pesticides (Group 1) and composting (Group 2), and addressing local concerns about soil contamination (Group 2) were also raised.

Participants discussed their lack of familiarity with the practical aspects of growing and using produce. Participant 8 highlighted that “a lot of people don’t know how to use the fruit and vegetables that they can grow”, pulling focus on the lack of familiarity with practical aspects of using the produce. Residents expect produce to be as convenient as shop-bought produce, deterring them from participating in these projects, as they might find the reality of gardening and harvesting less appealing. Community leaders also pointed out the lack of experience in gardening, crop rotation, and pest control, which may limit their ability to successfully manage these areas (Group 2; Group 3).

Participant 9 explained, “…making sure to tell them about the sunlight, the importance of sunlight, watering, how many times they should water”, stressing the importance of education on plant care. Proper information on these aspects can build participants’ confidence and commitment to growing food. Participants also discussed another critical gap in knowledge that exists in the younger generations noting, “My daughter was surprised to find out that garlic is essentially a root and grows under the ground” (Participant 20). Educating children on where food comes from “…learning about plants, what’s edible beyond what’s familiar, especially for children” (Participant 26). It can help mitigate hesitations around growing food and sustainability. These findings indicate the importance of information sharing infrastructure, for example signage with QR codes.

3.2.2. Ownership and Responsibility (n = 15)

Participants discussed security and safety concerns as significant barriers to engaging with a project like Edible Streets. Vandalism was highlighted as one of the most prominent concerns, evidenced by Participant 13, who noted that “the biggest problem with community planters is vandalisation–younger generations destroy and abuse the planters”. This issue is often rooted in a lack of information about the purpose and value of similar projects. As Participant 16 observed, “Vandalisation is a problem that comes from lack of education and information—it leads to demoralised people, and avoid(ing) taking ownership of the planters”, highlighting the hesitations of communities in taking ownership and responsibilities of such projects. Creating awareness using social media and other forms of engagement within the community was suggested as a path to mitigating the risks of vandalism, as discussed by Participant 9 “if you create that awareness within the community, possibly put it in a social media page like maybe Facebook or something, just to let people know, let them know that there’s this program going on”. Concerns about teenagers “hanging out” or homeless individuals occupying newly developed areas, deterring participation, were also raised by Group 3.

Establishing ownership and responsibility for the project is another crucial aspect that was discussed as a barrier to getting involved in an Edible Street. Participant 26 highlighted that the neighbourhood needs to come together to establish “How to do this in a way where there is shared ownership and responsibility, but also in a way that people can contribute in a way that works for them”. While this project aims to promote collective stewardship, Group 3 highlights the reluctance from residents to take ownership, especially in underutilised spaces, as their previous experience was that “People seem keen to join talks and film nights and discussions, but less keen to put in any work”.

Safety considerations were also discussed as a barrier to Edible Streets. Participant 16 also talks about physical restrictions like injury, limited mobility, and accessibility by saying “Restrictive movement due to injury does not allow (me) to get involved with gardening as it requires (me) to pick up heavy things and bend a lot”. This shows the importance of designing accessible and safe systems that accommodate various physical needs, thereby fostering broader participation.

3.2.3. Sustaining Long-Term Commitment (n = 18)

“Sustaining a regular commitment, so that this goes beyond the initial excitement of getting started”. (Participant 26) highlights the challenge of maintaining interest and engagement beyond the initial interest. This requires ongoing effort and planning to keep the community motivated and involved. As highlighted by previous events such as wildflower preparation and sowing and bulb planting, there has been minimal involvement from local residents (Group 3). This also shows the importance of Edible Street interventions that can grow with minimal maintenance and involvement, such as planting perennial edibles like herbs and fruit trees.

Securing the necessary permissions and licences from local councils can also be a time-consuming and challenging process. Participant 28 highlighted the extensive effort it took for them to secure permissions for another community project, noting that it took “a lot of work to persevere, with many emails and meetings” before they could start growing. Moreover, Participant 5 mentioned that there have been instances where “they tend to mow everything when they come around to mow the grass” furthering the sense of unwillingness to participate. Participants find it deeply discouraging when time and resources are invested in planting, only for them to be subsequently removed by these mowing activities. This highlights the importance of developing an application model for Edible Streets similar to applying for the installation of skips or the construction of drop kerbs, for example.

Investment in terms of both time and money was also discussed as a major barrier, as questioned by Participant 9, “where are you going to get all the money from to be able to invest to grow food in the community?”. Funding is important for the creation of Edible Street interventions. Participant 1 further emphasises the time commitment acting as a barrier by saying “Families are very busy, so just having the time to share your food or the time to organise the logistics of it could be quite challenging for people with children and people who’ve got busy jobs”. Moreover, transient populations, such as university students, often initiate projects but leave before seeing them through, leading to declining upkeep (Group 1).

Location and accessibility are crucial for the success of Edible Streets. However, ensuring that enough people are committed to maintaining these spaces can be challenging. “Getting enough people together to do it. Ensuring all members of the community looked after the space”. (Participant 34) highlights the barrier of location and accessibility for long-term commitment. Stakeholder group 2 also highlights the importance of promoting stewardship within the community, and the lack of communication avenues, especially if the Edible Streets span a larger area.

Projects like Edible Streets need strategic planning, securing funding, and fostering strong community leadership and engagement. Participants viewed it as a deterring factor as it is “hard to maintain motivation. Funding and long-term programming is needed to keep it alive” (Participant 14).

3.2.4. Climate and Context Concerns (n = 7)

Weather conditions, water accessibility, location, and soil quality present significant barriers to the success of Edible Streets. Participant 13 noted that “during winters it is difficult to maintain and grow anything in the gardens”, highlighting the need for knowledge of choosing to grow crops that cope in the different seasons. Additionally, Participant 1 pointed out the challenge of inconsistent food production, saying “it might not be very consistent because you might have loads of food at one time and then not very much food at others, so you can’t really sort of get into a routine”. This shows that knowledge of preserving produce is also key to community growing.

Water accessibility is another critical issue; as Participant 15 pointed out, it cannot be “expect(ed) people walk long distances or use their own water supply with rising prices”. Therefore, ensuring convenient access to free water sources, such as rainwater collection as part of the Edible Street designs, is essential. The soil condition and composition were also highlighted as a barrier to engaging in growing activities. Participant 15 mentions that “Planting uses lots of compost” as the soil in certain areas lacks the correct nutrient composition to be able to sustain growing edible plants. Water access during droughts, pollution from nearby urban areas, and soil quality, present logistical hurdles for the initiative as highlighted by Group 2 and Group 3. Ensuring access to water, especially in the face of rising costs and unreliable natural sources like the Barton Brook, is a critical issue according to Group 2. Studies have shown strategies for reducing pollution on edible plants in streetscapes, such as ensuring they are positioned away from areas where car exhaust fumes are most concentrated [

44].

Participant 18 also emphasised the “need for some oversight and responsibility taken by a group to make sure the land and plants were maintained” and protected against pests, as “apple trees in our garden were nearly destroyed by pests the year before last”. Animals attacking the plants also raised concerns among the participants “protecting it from birds and snails and whatever else is about” (Participant 7) is a substantial barrier and consideration that the community would need to pay attention to. Group 2 also raises concerns about contamination from pets, such as cat or dog waste, in planting beds. Furthermore, balancing the aesthetic expectations of the community with sustainable, eco-friendly green spaces is vital in preventing backlash from residents who may prioritise “tidy” appearances of verges and their streets (Group 2; Group 3).

To highlight the richness and depth of the qualitative data, selected participant quotes are used throughout this section to illustrate key themes and provide contextual nuance following the guidance on best qualitative reporting [

45]. These examples are not exhaustive but are chosen to reflect the diversity and significance of perspectives shared during the interviews, surveys, and workshops. To provide a clearer overview of the findings,

Table 5 below summarises the key drivers and barriers to Edible Streets linked to their corresponding participant responses.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the drivers and barriers to implementing Edible Streets as a community-led initiative, using the COM-B model of behavioural change [

31] as a framework to explore how capability, opportunity, and motivation influence community participation, policy, and governance (

Figure 5). The results showed that Edible Streets have significant potential to transform urban environments into nature-positive and climate-friendly spaces, offering a range of social, environmental, and health benefits to communities [

46]. The study revealed that participants were generally enthusiastic about the project’s potential to enhance social cohesion, improve health outcomes, and support environmental sustainability. However, identified challenges such as accessibility, maintenance, and sustaining community engagement, if left unaddressed, could make participation seem overwhelming for some. Through the lens of the COM-B model, these findings indicate that while the motivation to engage with Edible Streets was strong among participants, barriers in capability (e.g., knowledge of gardening techniques) and opportunity (e.g., lack of access to tools, water, and community infrastructure) may hinder widespread adoption. Triangulation was employed to strengthen the validity and comprehensiveness of the findings, integrating data from individual participants, stakeholder workshops, and secondary research. This multi-source approach enabled a more nuanced understanding of the barriers and drivers associated with the Edible Streets initiative.

Findings suggest that Edible Streets promote healthier lifestyles and mental well-being, with access to fresh produce and opportunities for physical activity positively impacting overall health. Long-term health benefits, such as improved nutrition from fresh fruits and vegetables, were highlighted [

47,

48], while gardening was noted as moderate exercise accessible even to those with limited mobility [

49]. Additionally, Edible Streets transform urban spaces into nature-positive environments, enhancing biodiversity, reducing waste, improving air quality, and creating wildlife habitats. By utilising underused spaces like grass verges, these initiatives contribute to climate change mitigation [

1] and improve neighbourhood environmental quality [

50]. However, environmental factors, such as weather, water access, and soil quality, complicate implementation. Rising water costs make relying on residents’ supplies impractical, emphasising the need for accessible public water sources [

51]. Poor soil quality or access to nutrient-rich soil can also limit success [

52]. These barriers highlight the importance of addressing logistical, educational, and environmental concerns to ensure the success of Edible Streets initiatives.

A key driver identified through community engagement was the potential of Edible Streets to foster social cohesion, strengthening local engagement through collaborative projects and community resilience [

33,

53]. By creating communal growing spaces, these initiatives provide platforms for sharing knowledge, fostering social networks, and bridging cultural divides, ultimately transforming urban areas into vibrant, interactive environments that promote collective well-being and reduce social isolation [

54,

55]. Additionally, engaging with nature through food growing has well-documented mental health benefits, such as reduced stress, lower anxiety, and improved psychological well-being [

56]. While social cohesion serves as a strong motivator, long-term commitment remains a significant barrier. Initial enthusiasm can wane without sustained community involvement, leading to neglected spaces and abandoned projects [

57]. Participant 26 captured this challenge, stating, “Sustaining a regular commitment, so that this goes beyond the initial excitement of getting started”, while Stakeholder Group 1 pointed out that transient populations, such as university students, often initiate projects but fail to maintain them over time. To address this challenge and allow social interactions, the Edible Streets model employs a three-level engagement framework to distribute responsibility and encourage sustained participation. Level 1 consists of core community members who take primary responsibility for the intervention, ensuring its ongoing care and development. Level 2 includes residents who regularly interact with and contribute to the space, helping with maintenance and benefiting from its produce. Level 3 comprises passers-by who, although not directly involved in upkeep, enhance the project’s visibility and provide natural surveillance, reinforcing a shared sense of ownership. This multi-tiered structure promotes a sense of belonging and collective ownership, vital for long-term engagement. The leader and active street residents sustain motivation, while passers-by contribute to awareness and support. This model helps build resilience and a culture of cooperation.

Participants highlighted the educational benefits of Edible Streets, emphasising how exposure to nature and learning about food production can instil a sense of responsibility and protectiveness toward the environment, and promote pro-environmental behaviour [

50,

52]. Education and collaboration are key drivers of the initiative, as they foster community engagement and the sharing of knowledge and skills. These combined benefits make Edible Streets a powerful tool for creating strong, connected, and environmentally conscious communities. Participant 20 emphasised the importance of early education, sharing, “My daughter was surprised to find out that garlic is essentially a root and grows under the ground”, while Stakeholder Group 2 viewed Edible Streets as an opportunity to build local resilience and stewardship. However, a barrier hindering full participation is the lack of knowledge and skills required to engage in Edible Streets projects. Many community members expressed uncertainty about what to grow, how to grow it, or how to engage neighbours and navigate land permissions. This lack of experience often leads to hesitation and concerns about taking full responsibility without adequate training [

32]. Furthermore, a lack of knowledge on utilising harvested produce emphasises the need for education on food preparation and preservation, which could enhance community involvement [

7,

58]. Participants highlighted the need for education on various aspects of food production. Participant 17 emphasised the importance of proper guidance, stating, “It’s important to give people proper instruction on how to grow and what to do when it comes to gardening… combinations of plants and seasonality of plants”. This concern was mirrored by Stakeholder Group 2, which raised issues related to the lack of understanding surrounding sustainable practices such as composting and soil contamination. The absence of accessible educational resources, such as a comprehensive guide on gardening and community organisation, also contributes to these barriers. Developing such resources, like the “How-to Guide” [

18], was crucial for addressing these gaps and supporting participants by providing practical and social skills necessary for success. This guide assists in overcoming the barriers related to education and collaboration, further driving the positive impacts of Edible Streets.

Logistical factors, including access to land and navigating legal processes, also pose significant obstacles. Many participants reported confusion regarding land ownership and permissions, which discouraged engagement due to perceived bureaucratic hurdles [

54]. The COM-B model [

31] highlights that opportunity is a critical factor in facilitating engagement; when barriers like these remain unaddressed, they can deter participation. The implications of legal frameworks are critical to overcoming these barriers. In the UK, the Right to Grow movement advocates for ensuring that urban residents have the legal right to grow food in public spaces. This movement promotes policies that make vacant or underused urban land accessible for food production. Edible Streets aligns with the goals of this movement by utilising public spaces, such as footpaths and verges, to create communal growing areas. These spaces can contribute to food security, environmental sustainability, and social cohesion, thus embodying the Right to Grow principle. However, the lack of clear legal frameworks for public land use remains a barrier. To address this, the Edible Streets team, along with the Oxfordshire County Council is developing an application process and licensing model for Highways adopted public land, particularly focused on footpaths and grass verges, to make it easier for communities to access land for food growing. This application and licensing system will simplify the process for communities to gain permissions for using these public spaces, eliminating bureaucratic obstacles and ensuring that residents have the opportunity to participate in Edible Streets projects. By clarifying land access and legal rights, this application and licensing model will support the sustainability and success of Edible Streets, empowering communities to engage with urban food growing and create thriving, productive spaces in the heart of their neighbourhoods.

The barriers to Edible Streets are addressed using the COM-B model’s components of capability, opportunity, and motivation. The creation of a comprehensive “How-to Guide” effectively addresses the capability barrier by providing participants with essential knowledge and practical skills in gardening, community organisation, and food preservation. The application process and licensing model, being developed in collaboration with Oxfordshire County Council, directly addresses the opportunity barrier by streamlining the process for accessing public land, particularly footpaths and verges, for urban food growing. By reducing bureaucratic hurdles, this model enables communities to utilise underused spaces, fostering wider participation in urban food-growing initiatives. Motivation is promoted through the initiative’s potential to improve mental health, strengthen social networks, and enhance environmental sustainability that drives community engagement. Additionally, the three-level engagement model cultivates a sense of collective ownership and responsibility, sustaining long-term participation. The study also contributes to international discourse on urban food growing by offering a scalable model that builds upon existing initiatives such as Incredible Edible Todmorden. Unlike traditional urban gardening projects, Edible Streets emphasises the structured use of public land, the application of the COM-B framework to urban policy and governance, and the participatory approach that incorporates three levels of users. A follow-up evaluation is being carried out to identify the long-term sustainability and impact of the Edible Streets interventions, focusing on how the three-tier engagement framework performs over time and how licensing and educational resources influence participation. The team is also supporting the implementation of additional Edible Streets projects.

4.1. Significance of the Research

This study advances the understanding of ‘Edible Streets’ as a promising approach for integrating green spaces in areas where one lives and works, aligning with UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2023. By prioritising food-producing plants, Edible Streets also addresses SDG 2—Zero Hunger [

2], advancing towards higher nutritional intake in the community, while sustainable and resilient growing practices contribute to SDG 13 (climate action) by introducing green infrastructure to help mitigate climate change, promote biodiversity, help reduce waste, and improve air quality [

1,

50]. Additionally, Edible Streets contribute to SDG 11 (sustainable and resilient communities) by acting as an instrument to create social cohesion and involving the community in designing and building their own surroundings promoting social resilience [

59]. The project promotes biodiversity conservation, sustainable use, and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits [

60] aligning perfectly with SDG 15 (life on land). Edible Streets also contribute to SDG 12 (Responsible production and consumption) by reducing food waste through local production and consumption, minimising packaging, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices [

2,

61].

Beyond Oxford, the Edible Streets model has broader national and international relevance. International case studies demonstrate that cities incorporating urban food production into planning policies see improved community resilience and environmental benefits. Additionally, Edible Streets aligns with smart city principles by leveraging underutilised spaces for multifunctional use, contributing to urban resilience and sustainability. This research offers an understanding of the specific environmental and social benefits of community-managed Edible Streets.

Built environment professionals have analysed residents’ experiences of residential streets and found that these spaces can be redesigned to create opportunities for connection to nature. This study identifies specific mechanisms and strategies that successfully fostered high levels of community participation in the Edible Streets project. It also synthesises the practical drivers and challenges of implementing the initiative into concrete recommendations for urban policy and planning for scalability. The findings offer a roadmap for policymakers, urban planners, and community groups to implement similar projects across the UK and internationally, demonstrating that Edible Streets is not just an innovative urban food-growing initiative but a holistic framework for sustainable, resilient, and inclusive cities. This study’s unique contribution lies in its investigation of a community-led model and its detailed analysis of local barriers and drivers supporting the development of practical implementation steps based on behavioural change models for actionable policy recommendations.

4.2. Future Research

This research is restricted to specific areas within the city of Oxford, and is focused on the local community and residents. While the insights gained are valuable, it is essential to recognise that different cities and communities may exhibit varied benefits and challenges. Future studies should consider replicating the research in diverse geographical locations to assess the transferability of the results given the potential of Edible Streets to contribute to sustainable urban development [

62].

A key area of focus is developing effective strategies to increase accessibility to information and knowledge about Edible Streets. The team has used the insights from the research to develop a comprehensive “How-to” guide, which is a critical step towards disseminating information. Knowledge sharing is essential for empowering communities to take ownership of their environments [

63]. A pilot project in a residential area in Oxford served as a valuable testing ground for implementing and evaluating Edible Streets initiatives [

64]. By monitoring changes in community well-being, environmental conditions, and social cohesion over time, researchers can gather valuable insights into the feasibility and effectiveness of the concept in a real-world setting. Developing a comprehensive application and licensing model is one of the next steps the team will take in realising the Edible Streets projects. This model should address issues such as property rights, liability, and community governance. Clear and equitable legal frameworks are crucial for facilitating community-led initiatives [

65]. By carefully considering these factors, it is possible to create a framework that supports community-led initiatives on publicly owned land, while protecting the interests of all stakeholders.