A Study of Working Conditions in Platform Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Sample and Respondent Characteristics

5. Results

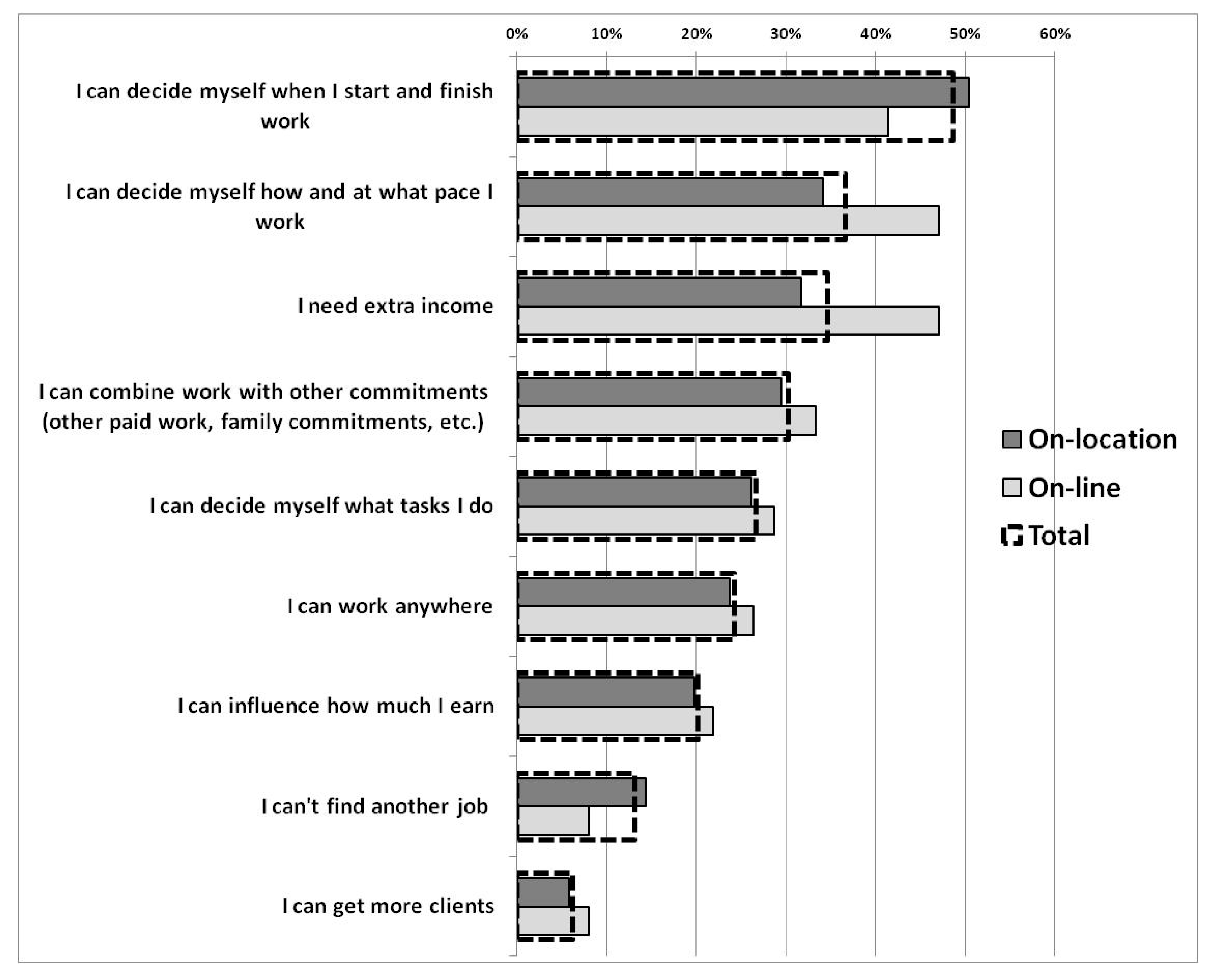

5.1. Motivations for Working Through Digital Platforms

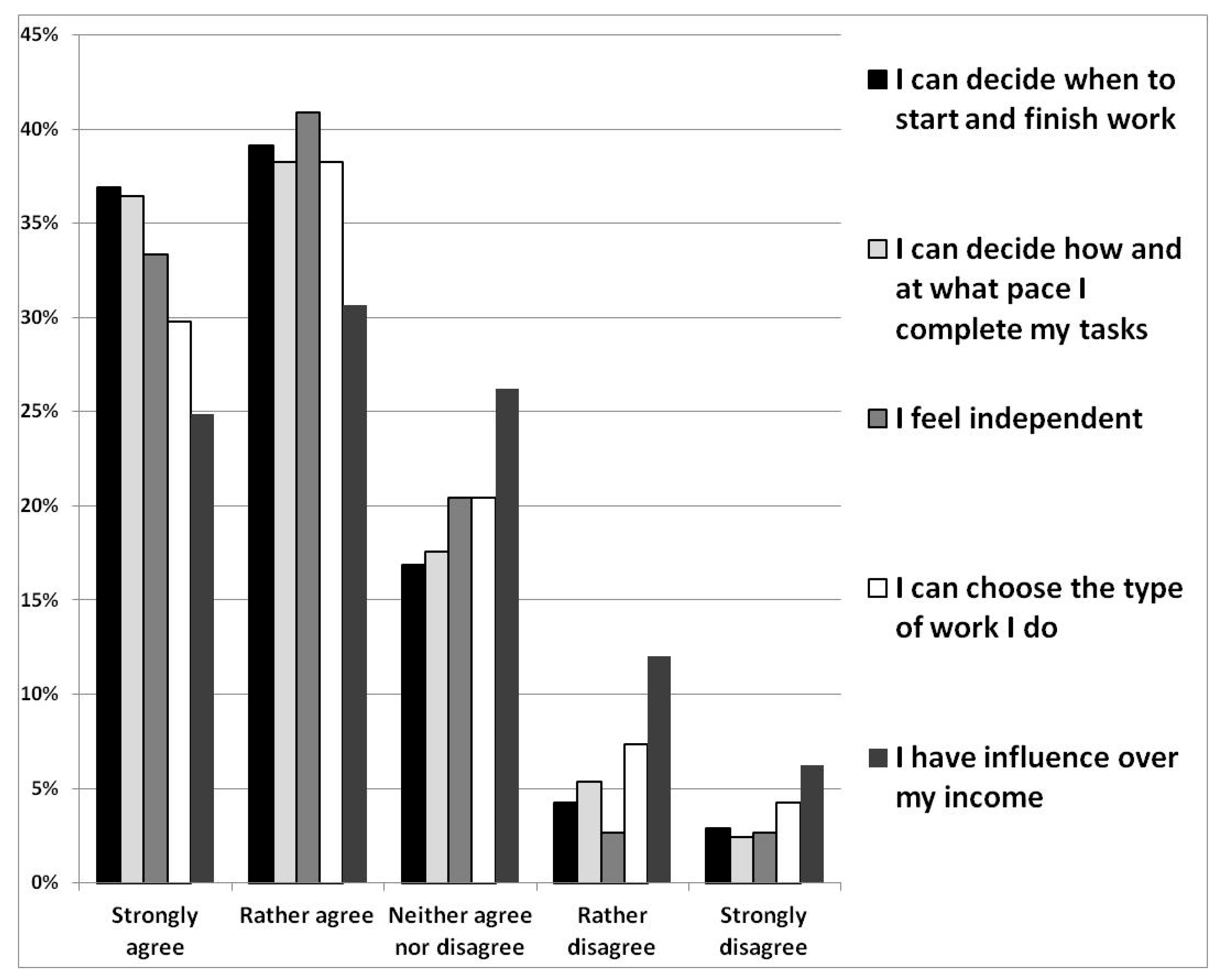

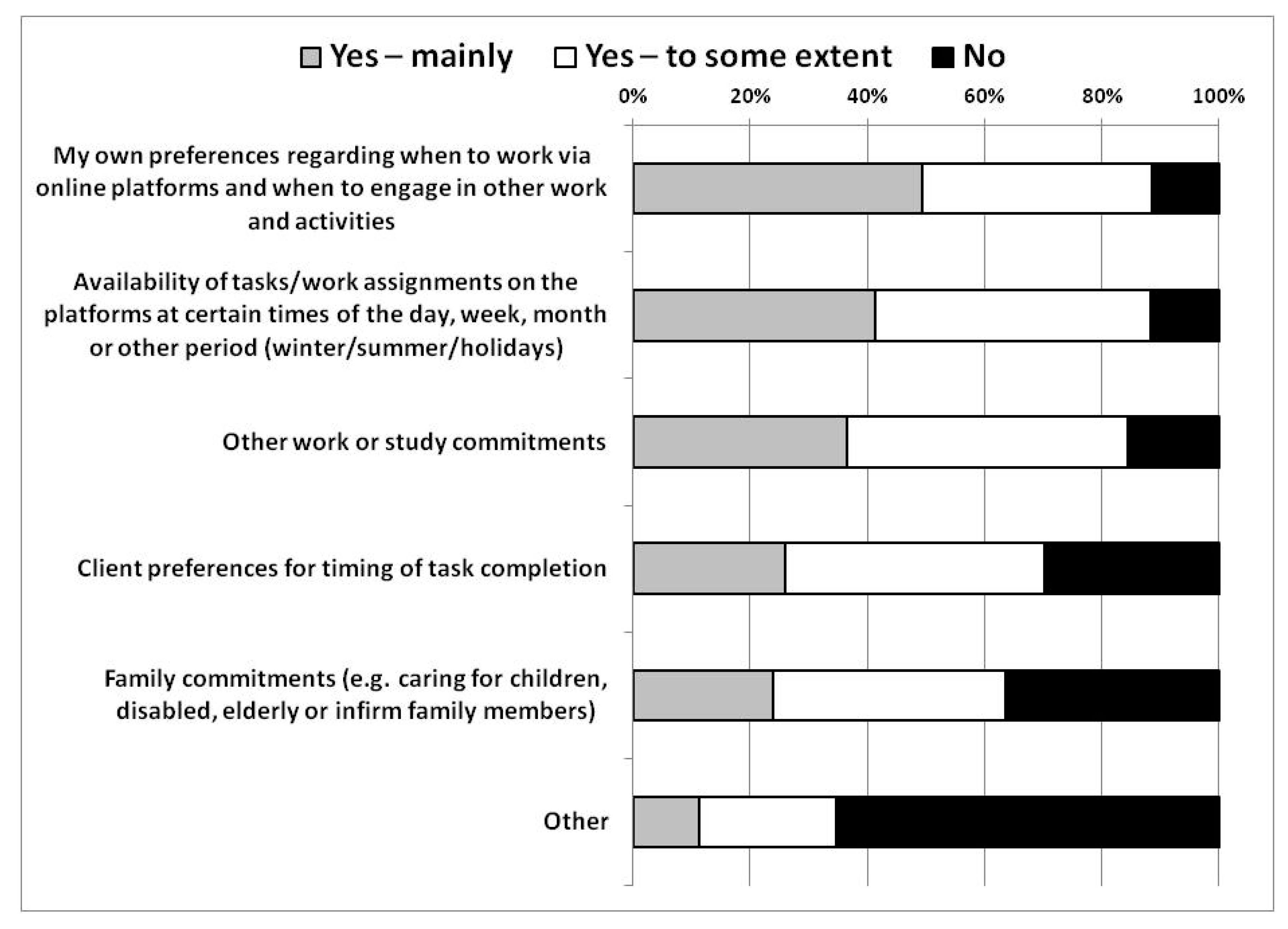

5.2. Autonomy in Task and Time Management

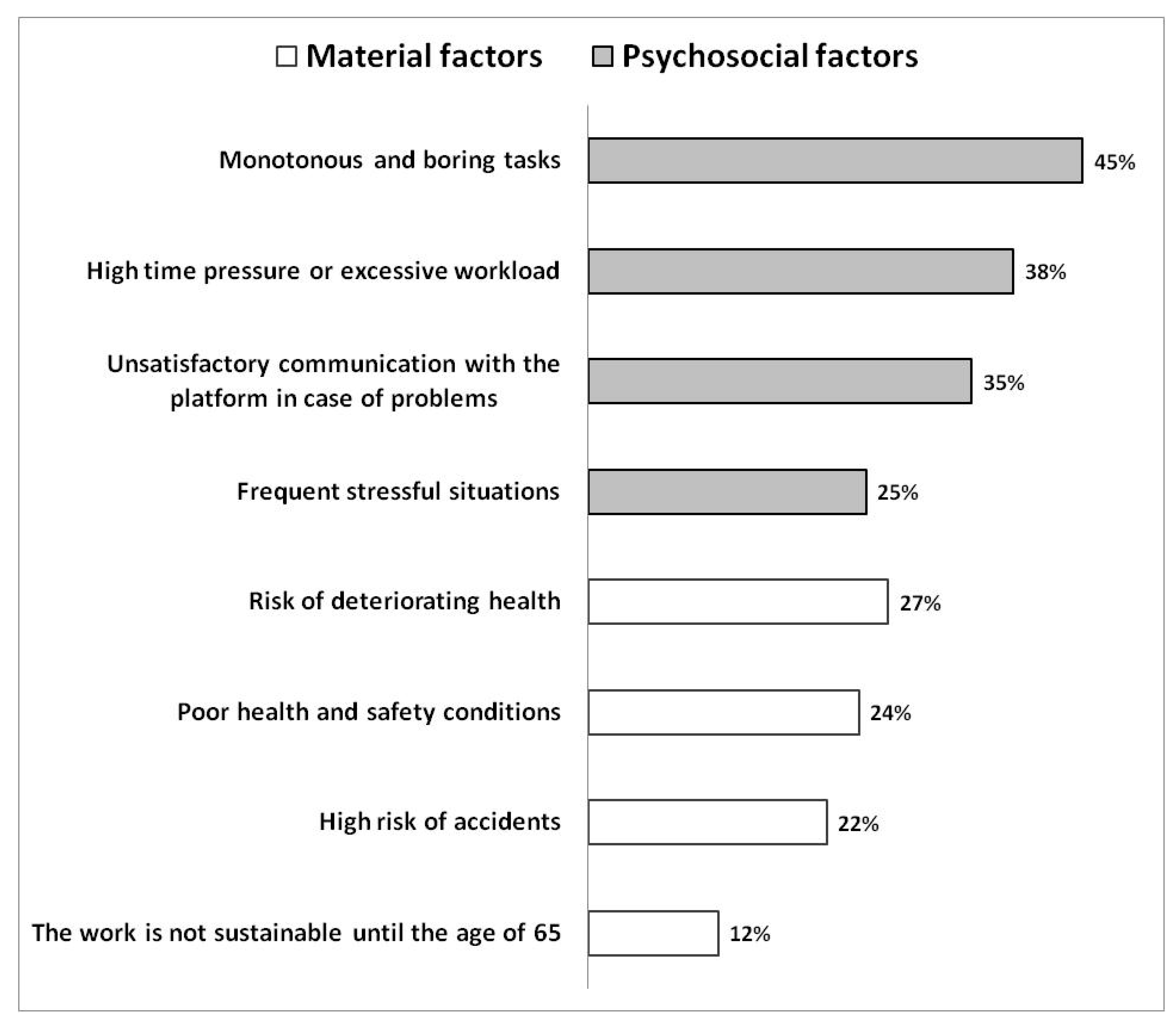

5.3. Workplace Safety and Health

5.4. Ratings of Selected Aspects of Working Conditions in Respondent Groups with Different Characteristics

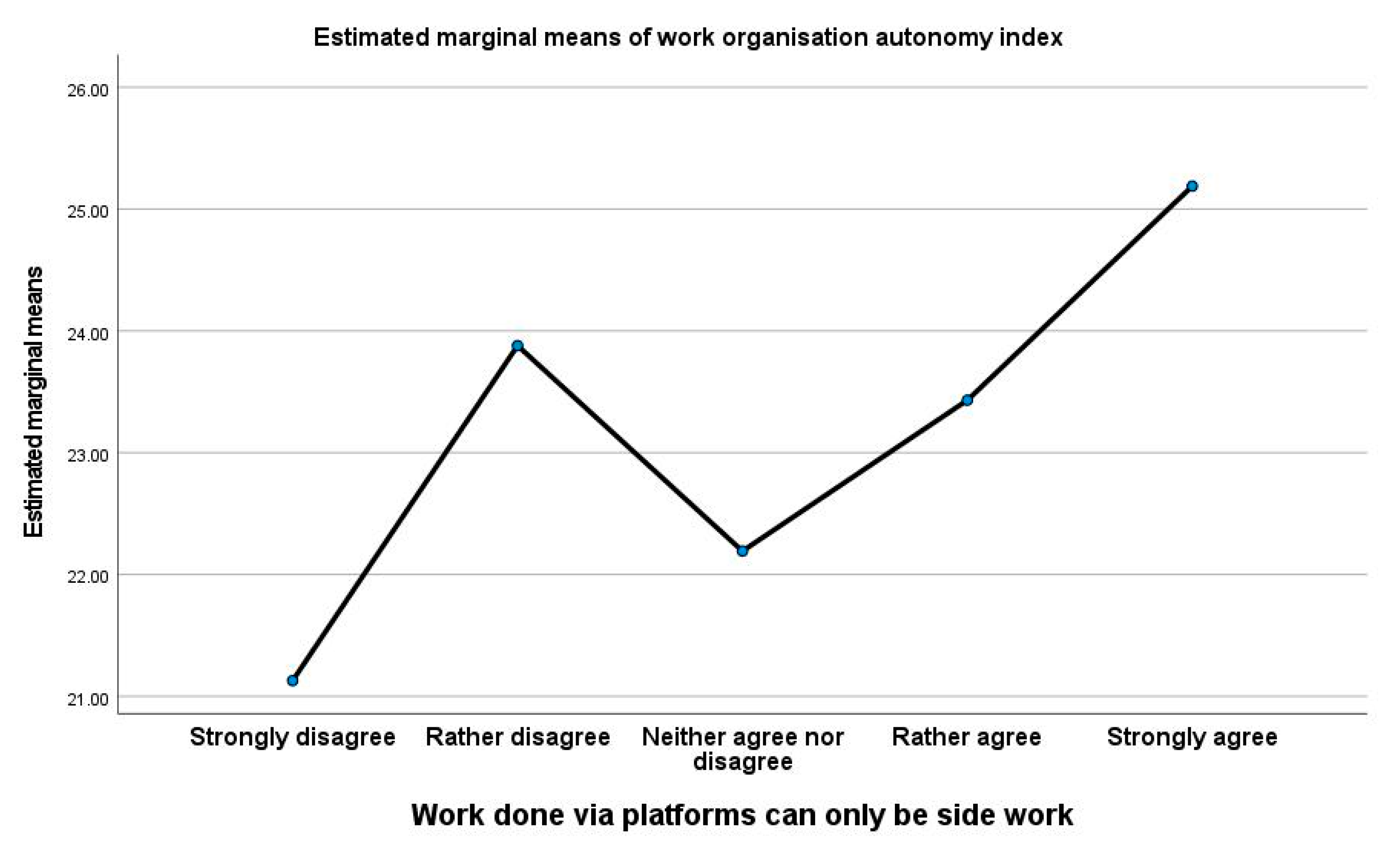

5.4.1. Assessment of Autonomy in Platform Work: Side vs. Primary Work

5.4.2. Autonomy Index

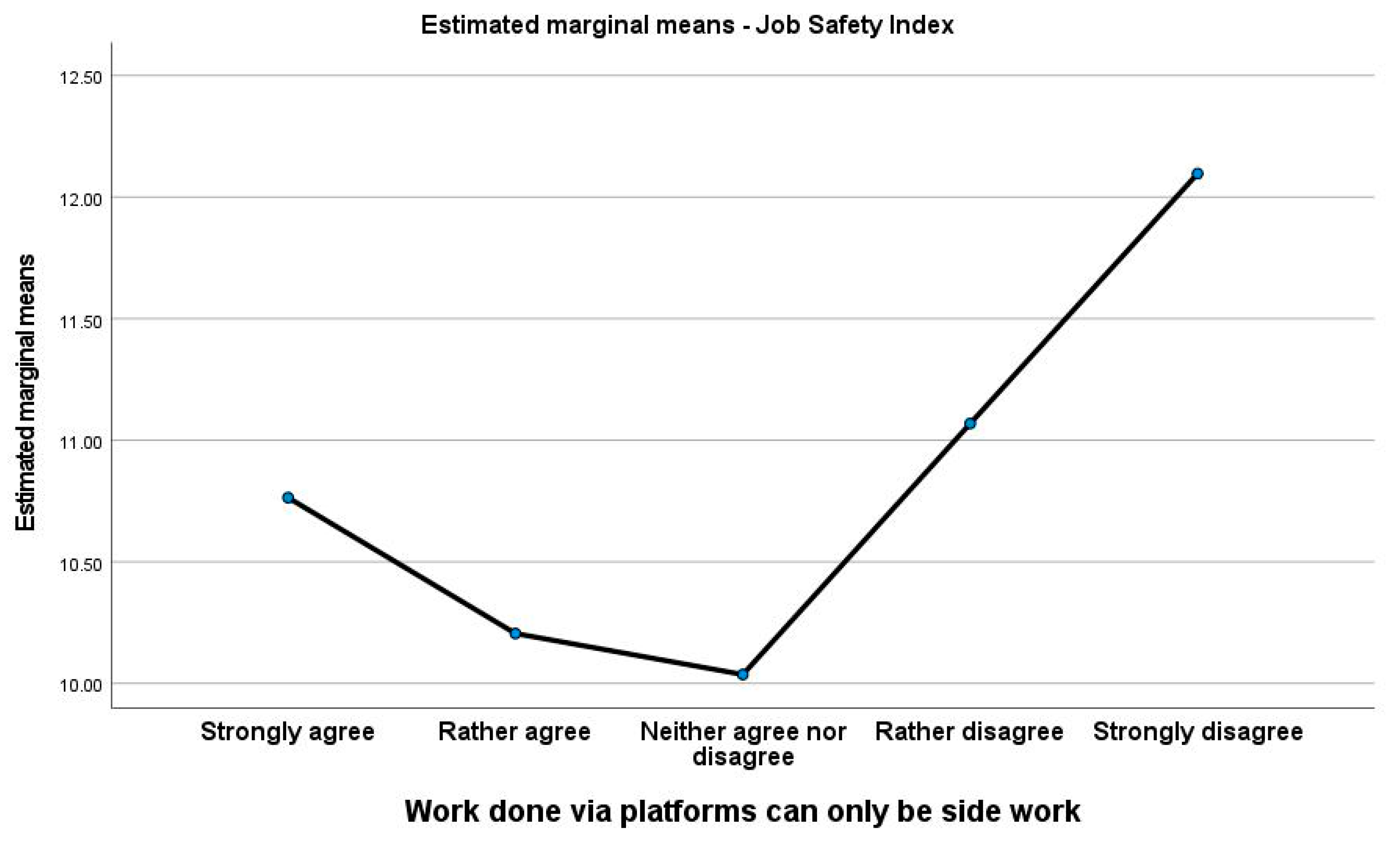

5.4.3. Health and Safety Ratings of Platform Work According to Preferences for Casual or Permanent Employment

- -

- My health may deteriorate if I continue this job for a longer period.

- -

- I can easily have an accident in this job.

- -

- I will be able to perform this job until I am 65 years old.

6. Discussion

7. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directive (EU) 2024/2831 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on Improving Working Conditions in Platform Work. Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/2831/oj/eng (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Khan, M.H.; Williams, J.; Williams, P.; Mayes, R. Caring in the Gig Economy: A Relational Perspective of Decent Work. Work Employ. Soc. 2023, 38, 1107–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, A.; Borkert, M.; Ferrari, F.; Heeks, R.; Wischmann, S. Towards Decent Work in the Digital Age: Introducing the Fairwork Project in Germany. Z. Arbeitswissenschaft 2021, 75, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, U.; Dhir, R.K.; Gobel, N. Digital Labour Platforms and Their Contribution to Development Outcomes. In The Elgar Companion to Decent Work and the Sustainable Development Goals; Moore, W.M., Scherrer, C., van der Linden, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 562–575. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, R. Sustainable Development in the Digital Economy: How Platform Exploitation Perception Influences Digital Workers’ Well-Being via Job Rewards and Job Security. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Platform Work: Maximising the Potential While Safeguarding Standards? Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2019/platform-work-maximising-potential-while-safeguarding-standards (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- EU-OSHA. Protecting Workers in the On-Line Platform Economy: An Overview of Regulatory and Policy Developments in the EU; European Risk Observatory Discussion Paper: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/sites/default/files/Protecting_Workers_in_Online_Platform_Economy.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Riso, S. Digital Age. Mapping the Contours of the Platform Economy; Eurofound: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kilhoffer, Z.; Rani, U.; Dhir, R.K. State-of-the-Art. Data on the Platform Economy (Deliverable No. 12.3); InGRID-2 Project: Leuven, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://www.inclusivegrowth.eu/files/Output/D12.3_EIND.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Pesole, A.; Urzí Brancati, M.C.; Fernández-Macías, E.; González Vázquez, I.; Biagi, F. Platform Workers in Europe (EUR 29275 EN); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC112157 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Urzí Brancati, M.C.; Pesole, A.; Fernández-Macías, E.; González Vázquez, I.; Biagi, F. New Evidence on Platform Workers in Europe: Results from the Second COLLEEM Survey (EUR 29958 EN); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC118570 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). On-Line Panel Survey of Platform Workers: Technical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/online-panel-survey-platform-workers-technical-report (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Berg, J.; Furrer, M.; Harmon, E.; Rani, U.; Silberman, M.S. Income Security in the On-Demand Economy: Findings and Policy Lessons from a Survey of Crowdworkers. Comp. Labor Law Policy J. 2016, 37. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2740940 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- De Groen, W.P.; Maselli, I. The Impact of the Collaborative Economy on the Labour Market. 2016. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2790788 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- de Groen, W.P.; Kilhoffer, Z.; Lenaerts, K.; Mandl, I. Employment and Working Conditions of Selected Types of Platform Work; Eurofound: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2018/employment-and-working-conditions-selected-types-platform-work (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Forde, C.; Stuart, M.; Joyce, S.; Oliver, L.; Valizade, D.; Alberti, G.; Hardy, K.; Trappmann, V.; Umney, C.; Carson, C. The Social Protection of Workers in the Platform Economy. European Parliament, Committee on Employment and Social Affairs. 2017. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/614184/IPOL_STU(2017)614184_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Huws, U.; Spencer, N.H.; Syrdal, D.S.; Holts, K. Work in the European Gig Economy: Research Results from the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy; Foundation for European Progressive Studies: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://feps-europe.eu/publication/561-work-in-the-european-gig-economy-employment-in-the-era-of-online-platforms/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). Artificial Intelligence, Platform Work and Gender Equality; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.; Furrer, M.; Harmon, E.; Rani, U. Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_645337.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Serfling, O. Crowdworking Monitor Nr. 1. Hochschule Rhein-Waal. 2018. Available online: https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Meldungen/2018/crowdworking-monitor.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Barcevičius, E.; Gineikytė-Kanclerė, V.; Klimavičiūtė, L.; Ramos Martin, N. Study to Support the Impact Assessment of an EU Initiative to Improve the Working Conditions in Platform Work: Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/454966ce-6dd6-11ec-9136-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- CIPD. To Gig or Not to Gig? Stories from the Modern Economy; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/to-gig-or-not-to-gig_2017-stories-from-the-modern-economy_tcm18-18955.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Hall, J.V.; Kreuger, A.B. An Analysis of the Labor Market for Uber’s Driver-Partners in the United States. NBER Working Paper No. 22843; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22843/w22843.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Berger, T.; Frey, C.B.; Levin, G.; Danda, S.R. Uber Happy? Work and Well-Being in the “Gig Economy”; Oxford Martin School: Oxford, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/201809_Frey_Berger_UBER.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Christie, N.; Ward, H. The Health and Safety Risks for People Who Drive for Work in the Gig Economy. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, A.; Stark, L. Uber’s Drivers: Information Asymmetries and Control in Dynamic Work. 2015. Available online: https://algorithmsatwork.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/rosenblat-stark-information-asymmetries-and-control-in-dynamic-work-cscw-2016.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Rosenblat, A.; Stark, L. Algorithmic Labor and Information Asymmetries: A Case Study of Uber’s Drivers. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 27. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/4892/1739 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Schörpf, P.; Flecker, J.; Schönauer, A.; Eichmann, H. Triangular Love-Hate: Management and Control in Creative Crowdworking. New Technol. Work Employ. 2017, 32, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; MacDonald, I.T. Modeling the Job Quality of ‘Work Relationships’ in China’s Gig Economy. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 855–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: The Role of Digital Labour Platforms in Transforming the World of Work; ILO Flagship Report: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_771749.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Tran, M.; Sokas, R.K. The Gig Economy and Contingent Work: An Occupational Health Assessment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e63. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5374746 (accessed on 14 July 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilhoffer, Z.; Rani, U.; Dhir, R.K.; Mandl, I. Study to Gather Evidence on the Working Conditions of Platform Workers; DG EMPL: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, F.G.; Benavides, F.R.; Serra, C.; Martinez, J.M.; Castaño, P. Associations Between Temporary Employment and Occupational Injury: What Are the Mechanisms? Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 416–421. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2078100 (accessed on 14 July 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huws, U. A Review on the Future of Work: On-Line Labour Exchanges or Crowdsourcing. OSHwiki. 2015. Available online: https://oshwiki.osha.europa.eu/en/themes/review-future-work-online-labour-exchanges-or-crowdsourcing (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Lee, M.K.; Kusbit, D.; Metsky, E.; Dabbish, L. Working with Machines: The Impact of Algorithmic and Data-Driven Management on Human Workers. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 1603–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Mohlmann, M.; Zalmanson, L. Hands on the Wheel: Navigating Algorithmic Management and Uber Drivers’ Autonomy. ResearchGate. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319965259 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Bérastégui, P. Exposure to Psychosocial Risk Factors in the Gig Economy: A Systematic Review. ETUI. 2021. Available online: https://www.etui.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Exposure%20to%20psychosocial%20risk%20factors%20in%20the%20gig%20economy-a%20systematic%20review-2021.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Pastuh, D.; Geppert, M. A ‘Circuits of Power’-Based Perspective on Algorithmic Management and Labour in the Gig Economy. Ind. Beziehungen 2020, 27, 179–204. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/253726/1/indbez-v27i2-05.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Graham, M.; Lehdonvirta, V.; Hjorth, I. Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy. Work Employ. Soc. 2019, 33, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurofound. European Working Conditions Telephone Survey (EWCTS). 2021. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/data-catalogue/european-working-conditions-telephone-survey-2021-0 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

| Study Source | Country/Scope | Methodology | Surveyed Aspects of Working Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CERIC, University of Leeds (2017) [16] | Global (AMT, Clickworker, etc.) | Online survey (1200 workers) | Motivation, working time, pay, job satisfaction, autonomy, stress, social protection |

| Ipsos-MORI, (2016–2017) [17] | 6 EU countries and Switzerland | Online + offline surveys, interviews | Flexibility, platform communication, client ratings, stress, health and safety, work–life balance |

| COLLEEM (JRC + DG EMPL, 2017) [10] | 14 EU countries | Online panel survey (32,409 respondents) | Income, motivation, autonomy, work environment, stress, deadlines, skill development |

| COLLEEM (JRC + DG EMPL, 2018) [11] | 16 EU countries | Online panel survey (38,022 respondents) | Pay, flexibility, monitoring, impact of ratings, social interaction, health risks |

| EIGE (2020) [12,18] | 10 EU countries | Online survey (4932 workers) | Work-life balance, low/unfair pay, discrimination, skill development, unpredictability |

| ILO (2015, 2017) [19] | 75 countries | Surveys + Skype interviews + Fair Crowd Work data | Wages, work availability, intensity, communication, social protection |

| Civey GmbH (2018) [20] | Germany | Online panel | Demographics, motivation, pay, satisfaction |

| EU study (2021) [21] | 9 EU countries | Mixed methods | Income unpredictability, autonomy, safety, isolation, job satisfaction |

| UK national survey (2016) [22] | United Kingdom | Survey (5019 respondents) | Working time, flexibility, control, job satisfaction, skill development, wellbeing |

| Multi-country study [15] | 8 EU countries | Semi-structured interviews (41 people) | Employment status, work intensity, taxation, environment, relationships, training |

| Uber + BSG (2014–2015) [23] | United States | Surveys (601 & 833 people) + admin data | Driver demographics, income, motivations |

| Uber—London (2018) [24] | United Kingdom | Telephone interviews (1001 drivers) | Income, working hours, motivation, flexibility, control, wellbeing |

| Couriers’ & drivers’ survey [25] | urban areas | Face-to-face interviews + online questionnaires | Work–life balance, risk awareness, safety responsibility, support from peers/supervisors |

| CERIC + EU project (2016–2017) [16] | 8 EU countries | interviews with experts (50) + survey (1200 workers) | Pay, flexibility, intensity, skill development, job insecurity |

| Forum-based analysis [26,27] | English-speaking | Post analysis (1350) + 7 interviews | Algorithmic management, driver evaluations, autonomy, and control |

| Creative crowdsourcing interviews (2015) [28] | Global | 20 face-to-face interviews | Working time, work-life balance |

| Work pressure survey (2020) [5] | China | Questionnaire, food delivery riders (9576) | Working time, work pressure, platform HRM practices |

| Job quality in the gig economy [29] | China | Questionnaire (500 gig economy workers) + 24 in-depth interviews | Salary and welfare, work enjoyment, work environment, health and safety, career development, work stress, |

| Area | Aspects Assessed |

|---|---|

| Motivations for working through digital platforms | Sense of independence Ability to choose start/end times, tasks, and the pace of work Influence over income |

| Autonomy in task and time management | Ability to reconcile personal and work life Long working hours (>10 h/day) Working evenings/nights/weekends |

| Workplace safety and health | Health risks Accident risk Task monotony Workload pressure; stress Contact with colleagues Work sustainability (until age 65) Information about risks |

| Such Work Can Only Be a Sideline → To What Extent Do You Agree with the Following Statements Regarding Your Work via the Platform: | Chi-Square Test (12, N = 450) | Goodman and Kruskal’s Measure of the Strength of the Relationship γ |

|---|---|---|

| I feel independent in this job. | 91.8; p < 0.001 * | 0.01; p = 0.9 |

| I have control over when I start and finish work. | 107.1; p < 0.001 * | 0.24; p < 0.001 * |

| I have a say in what kind of work I do. | 95.9; p < 0.001 * | 0.21; p < 0.001 * |

| I have control over how and at what pace I work. | 115.1; p < 0.001 * | 0.16; p < 0.01 * |

| I have influence over how much I earn. | 94.1; p < 0.001 * | 0.2; p < 0.001 * |

| I find it easy to balance work and private life. | 72.1; p < 0.001 * | 0.15; p < 0.05 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pawłowska, Z.; Ordysiński, S.; Pęciłło, M.; Galwas-Grzeszkiewicz, M. A Study of Working Conditions in Platform Work. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146536

Pawłowska Z, Ordysiński S, Pęciłło M, Galwas-Grzeszkiewicz M. A Study of Working Conditions in Platform Work. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146536

Chicago/Turabian StylePawłowska, Zofia, Szymon Ordysiński, Małgorzata Pęciłło, and Magdalena Galwas-Grzeszkiewicz. 2025. "A Study of Working Conditions in Platform Work" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146536

APA StylePawłowska, Z., Ordysiński, S., Pęciłło, M., & Galwas-Grzeszkiewicz, M. (2025). A Study of Working Conditions in Platform Work. Sustainability, 17(14), 6536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146536