1. Introduction

The concept of inclusive tourism was formulated in the second decade of the 21st century on the basis of the concept of “inclusive development”, defined as follows by the UNDP [

1]: “

People are excluded from development because of gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, disability or poverty. Development can only be inclusive—and reduce poverty—if all groups of people contribute to creating opportunities, sharing the benefits of development and participating in decision-making”. Lawson [

2] adds that inclusive development requires an understanding of economic development in relation to place, politics and society, geared not only towards growth, but above all towards caring for people and the environment. Undoubtedly, economic growth is essential for inclusive growth, which is also a sustainable development goal.

Inclusive tourism boils down to ensuring that all people regardless of their physical and social limitations have access to and use of spaces, communities, land, hospitality, services, food, pathways and mobility, thereby contributing to social well-being and overall economic value. It is supposed to bring happiness to people, allow everyone without exception to use tourist attractions and enable participation in various tourist activities [

3].

Since this concept refers to a broad social aspect, many overlapping concepts can be found in the literature, including accessible tourism, tourism for the poor, social tourism, responsible tourism, integrated tourism, tourism without barriers, and tourism for all [

4]. However, the concept of inclusive issues seems to have a broad meaning; therefore in justified articles, this concept should be understood as involving related concepts.

Expanding the participation of marginalised host communities in the development of tourist destinations is the basis of the concept of inclusive tourism. The impetus for building this concept was empirical experience resulting from local initiatives on small and medium scales, which included new people and new places in tourism, taking social, spatial and economic integration into account [

5]. Therefore, inclusive tourism is part of a broader sustainable development strategy, in which social aspects are considered [

6].

Sustainable development and sustainable tourism cover practically all spheres of functioning of the modern world, including social inclusion and inclusive tourism [

7]. Sustainable tourism clearly emphasises social aspects, in addition to minimising negative impact of tourismification on the local natural environment and cultural heritage it also indicates the possibility of employing local residents in tourist services, striving for the development of the region and promoting local cultural products, as well as respect for natural resources and local communities.

Currently, an inclusive approach to the economy is a dominant topic in discussions on sustainable development. According to Bakker and Messerli [

8], inclusive growth can be achieved in the long term by increasing employment opportunities and producing goods and services, rather than just redistributing resources to the poor. It can therefore be assumed that inclusive growth is more beneficial for the tourism sector than public subsidies for tourism accessible to the poor. A study conducted in Ha Long Bay in Vietnam showed that despite the rapid development of tourism in this area, tourism has not contributed to inclusive economic growth at all [

9]. Robin Biddulph [

10] draws similar conclusions based on a study conducted in Siemp Reap, Cambodia. The results of this research indicate that an inclusive approach in business, based on the neoliberal model of economic growth, does not work in practice. It is limited to the economic dimension and is not linked to a policy agenda, such as efforts to overcome structural inequalities that are a barrier to development for the poor. On the other hand, the inclusion of the poor in the market economy can be a direct way out of poverty [

11]. This is indicated by the views of many researchers [

12,

13,

14].

When analysing the position of inclusive tourism in the concept of sustainable development, it is worth taking a closer look at the document called the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

15]. It is an action plan that was adopted by the UN member states in 2015. The adoption of the 2030 Agenda is an unprecedented event, as all 193 member states of the United Nations (UN) have committed to taking action to implement the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These objectives are focused on ensuring a decent life for all inhabitants of the world, peace and economic progress, while protecting the natural environment and combating climate change; therefore, they aim to combat the most important global challenges. The 2030 Agenda focuses on five key aspects (the so-called 5Ps): people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership.

The Sustainable Development Goals therefore cover a variety of areas and emphasise inclusion at different levels. Tourism itself is directly included in only three of the Sustainable Development Goals:

Goal 8.9. (8. Economic growth and decent work), promoting sustainable tourism based on creating new jobs and promoting local culture and products;

Goal 12.B. (12. Responsible consumption and production), based on developing and implementing tools for monitoring the impact of sustainable development on sustainable tourism;

Goal 14.7. (14. Marine life), focusing on increasing the economic benefits of small island developing states, including through sustainable tourism management.

It is known, however, that tourism has strong indirect connections and an influence on most of the goals of Agenda 2030. Tourism is, after all, a social, economic, spatial, cultural phenomenon. It draws from various areas of life and has major influence on them. The goals are global in nature and translate into those, among others, national, regional, industry, including tourism and social inclusion.

According to Scheyvens and Biddulph [

16], inclusive tourism is a concept that draws attention to the involvement of marginalised communities in the process of tourism offer creation and tourism consumption, as well as the ethical sharing of benefits associated with tourism development, with the participation of local communities [

17].

Inclusive tourism is undoubtedly linked to other concepts of sustainable tourism. Scheyvens and Biddulph [

16] attempted to define the concept of inclusive tourism in the context of sustainable tourism. In their view, the concept focuses on three pillars: economic, in which the economic benefits of tourism development should be appropriately distributed to marginalised communities; community involvement in tourism development planning; and an ethical relationship between production and consumption. Also Bakker et al. [

8] defined aspects of sustainable tourism in the concept of inclusive tourism, identifying three pillars growth of tourism opportunities, i.e., benefits to local people from tourism development; equitable access to the benefits of tourism development; and a pillar focusing on equity in tourism ensuring, among other things, that there are no differences in remuneration based on religion, gender or other individual characteristics.

The Sustainable Development Goals [

15] detail the tasks in each sphere of global functioning and, although nowhere directly stated, some of the goals in the concept of sustainable development can be linked to inclusive tourism.

Table 1 below comprises a list of the goals and tasks of the 2030 Agenda that can be considered from the point of view of inclusive tourism.

Tourism utilises various aspects and areas of life, e.g., infrastructure, transport. Among the tasks of the 2030 Agenda, attention has been repeatedly drawn to the aspect of social inclusion. The tasks emphasise, among others, the elimination of poverty, gender equality and social empowerment, easy access to environmentally friendly energy, full employment, building a sustainable technical and social infrastructure, development of an inclusive economy, eliminating social discrimination, exclusion and promoting equality.

Without social inclusion, we cannot talk about inclusive tourism; tourism is a multidimensional phenomenon, it draws from various areas of life, uses various areas of functioning of the community, regions in which it is implemented. For example, in Goals 11.2 and 11.7, attention was drawn to the issue of developing transport or recreational infrastructure, which should be adapted for people with special needs. Goals 8.5 and 10.2 emphasise equality in relation to employment, which translates into employment in the tourism industry. Goal 4.7 is to make all people aware and educate them that they have their rights, cannot be socially excluded and everyone, regardless of their specific needs and differences, can be a “citizen of the world”, identifying as a member of the global, tourist community.

The concept of inclusive tourism development allows for a constructive and critical approach to tourism [

18]. It is a holistic concept that focuses on reducing the gap between the poor and the rest of society; it implies greater participation in well-being of marginalised social groups [

8]. Observing the evolution of organised social tourism it can be noticed that the circle of beneficiaries is gradually widening: from low-income families, people with special needs, to vulnerable people (e.g., refugees) and groups discriminated against in a given society [

4,

19]. Crespi-Vallbona, Ortiz and Zuniga [

20] even highlighted the possibilities of including people demobilised after the internal conflict in Colombia in tourism by creating a sustainable tourism development model that promotes social inclusion.

2. Review of Key Bibliometric Studies

The topics of accessible, inclusive and sustainable tourism are gaining increasing attention among researchers. This growing interest is reflected not only in the expanding body of literature but also in the rising number of bibliometric studies analysing these fields. The evolving discourse on tourism accessibility, social inclusion and sustainability has been highlighted in recent research, emphasising their significance for both academic inquiry and practical implementation. The proliferation of bibliometric analyses further underscores the structured efforts to map key trends, research gaps and interdisciplinary connections within these domains.

In order to identify studies at the intersection of sustainable development and inclusive tourism, a literature review was conducted focusing on research that combines the concepts of inclusive tourism (or related terms) and sustainable tourism. Despite increasing academic attention to both topics separately, no bibliometric studies were found that explicitly analyse the interrelation between inclusive tourism and sustainable development. Therefore, the following section presents selected recent bibliometric studies focused either on sustainable tourism or on inclusive tourism and associated terms. Only the most recent and thematically relevant bibliometric works have been included, as they best reflect the current state of knowledge in these two distinct areas.

Research on sustainable tourism has been conducted for several decades, with significant changes dating back to the 1970s. Considering the extensive literature on the topic of sustainable tourism, numerous bibliometric studies have also been conducted. Due to the huge number of such studies, this article will be focused on highlighting the latest and most relevant bibliometric analyses from the point of view of the authors’ research. Agarwal et al. conducted a structural topic modelling of 3289 articles published between 1978 and 2022, identifying 25 key topics divided into macro-, meso- and micro-levels. In the study, they highlight significant publication milestones in 2006 and 2016, correlating with global sustainability initiatives and emerging research areas such as technology integration and individual sustainable behaviour [

21].

Similarly, Kapoor and Jain [

22] carried out a bibliometric analysis of 25 years of sustainable tourism literature, focusing on thematic developments and future research directions. Their findings reveal a shift from research on environmental and stakeholder impacts to contemporary issues such as community-based tourism, technological challenges and disaster risk management after 2015. They advocate for interdisciplinary approaches to addressing these evolving topics. Geng et al. [

23] used CiteSpace to map the intellectual structure of sustainable tourism research, identifying influential authors, institutions and networks. Their analysis underscores the dynamic nature of the field, with increasing emphasis on topics such as climate change adaptation, ecotourism and policy development. Kumar et al. [

24] explored a decade of progress in sustainable tourism using bibliometric methods, highlighting the growing trend in publications and citations. Their study allows to indicate diversification in research topics, including sustainable destination management, pro-ecological tourist behaviours and the integration of smart technologies to promote sustainability in tourism practices.

It is worth noting, however, that in numerous bibliometric studies on inclusive tourism and related concepts, important links are increasingly being demonstrated between inclusive tourism, sustainable tourism and sustainable development. These analyses reveal that inclusive tourism is not only an essential element of sustainable travel policies, but is also consistent with broader goals of equal access, social inclusion and environmental responsibility. The growing scholarly interest in this intersection emphasises the need for an integrated research approach taking the economic, social and environmental dimensions of tourism development into account.

In one such study by Qiao, Hou, Huang and Jia [

25], the authors present a bibliometric review of inclusive tourism research using the Web of Science database. Their findings indicate that inclusive tourism research has expanded over the past 16 years (2008–2023), but its overall volume remains limited. It is highlighted that Massey University and the University of Gothenburg are leading institutions in this field. In addition, international collaborations have developed, involving China, Japan and other countries. The inherent link between inclusive tourism and sustainable development is demonstrated in the study, especially with regard to reducing social exclusion and inequality. Similar conclusions were reached by Hernández Sales and López Sánchez [

26]. In their bibliometric analysis covering the 2000–2021 period, an increase was shown in the number of publications since 2018, especially in the fields of geography and economics. It was found that terms such as “inclusive tourism” and “sustainable tourism” are increasingly linked, suggesting a shift in research focus towards management and sustainable development. Henriquez et al. [

27], in their study on the same topic, using the Scopus database, mapped the progress of accessible tourism research by analysing 254 articles. According to this article, Australia has become a leading research centre. Furthermore, the role of new technologies is presented, such as of smartphones and virtual reality, in the development of accessible tourism. While sustainability is recognised, the direct relationship between accessible tourism and sustainable development remains unexplored. Similar conclusions were reached by Qiao et al. [

25], who identified six key research modules in accessible tourism based on a bibliometric analysis of 213 articles (2008–2020). The University of Technology Sydney emerged as the most productive institution. The growing interest in “experience” and “participation” in the field were noted, suggesting new directions for research.

Gulati, Duggal and Kumar [

28] focused on Scopus-indexed publications concerning accessible tourism (2000–2021). Using VOSviewer to visualise data, the authors identified key research trends, most frequently cited articles and keyword co-occurrences. From the study, it was concluded that accessible tourism research has been increasing in number in recent years. A fairly important work from the perspective of bibliometric studies is the article by Leiras and Caamaño-Franco [

29]. The authors analysed the terminology used in accessible tourism studies in 613 documents from the Scopus database (1984–2022). The authors found that in previous studies, the term “accessible tourism” was not consistently used but rather other related terms, which made it difficult to search for relevant literature. They identified four distinct phases of research development, emphasising the need for standardised terminology in future studies.

In conclusion, the absence of bibliometric analyses that jointly explore the relationship between sustainable tourism and inclusive tourism (or related terms) reveals a clear research gap. This intersection remains underexplored from a bibliometric perspective, highlighting the need for future studies to bridge these domains and examine their conceptual and practical synergies.

3. Research Objective and Methodology

The reviewed studies allow to indicate that accessible tourism research has grown significantly over the past two decades. The relevance of sustainable tourism and sustainable development in the context of accessibility has been acknowledged in many studies. However, none of the reviewed bibliometric analyses are explicitly focused on the direct relationships between these concepts. This gap underscores the need for a comprehensive study examining the interconnections between accessible tourism and sustainability, which will be the primary objective of the present research.

The aim of the research was expressed through the following research questions:

Q1. What are the most frequently studied themes in the literature on accessible tourism and sustainability?

Q2. What gaps exist in the current research on accessible tourism that need to be addressed to enhance understanding and practice?

Q3. What emerging trends can be identified in the recent studies of accessible tourism and its relationship with sustainability?

In the present study, a scoping review was used as the primary research method, which is a type of literature review that has gained recognition as a method for mapping existing knowledge within a given field. It typically involves a fairly comprehensive search of the literature related to a broad topic [

30]. Unlike a systematic review, which focuses on a narrowly defined research question and includes only pre-selected, quality-assessed studies, a scoping review covers a wider thematic scope and incorporates diverse study designs. Its purpose is not to critically appraise the included studies or to provide definitive answers, but rather to offer an overview of existing research and to identify knowledge gaps for future investigation [

31].

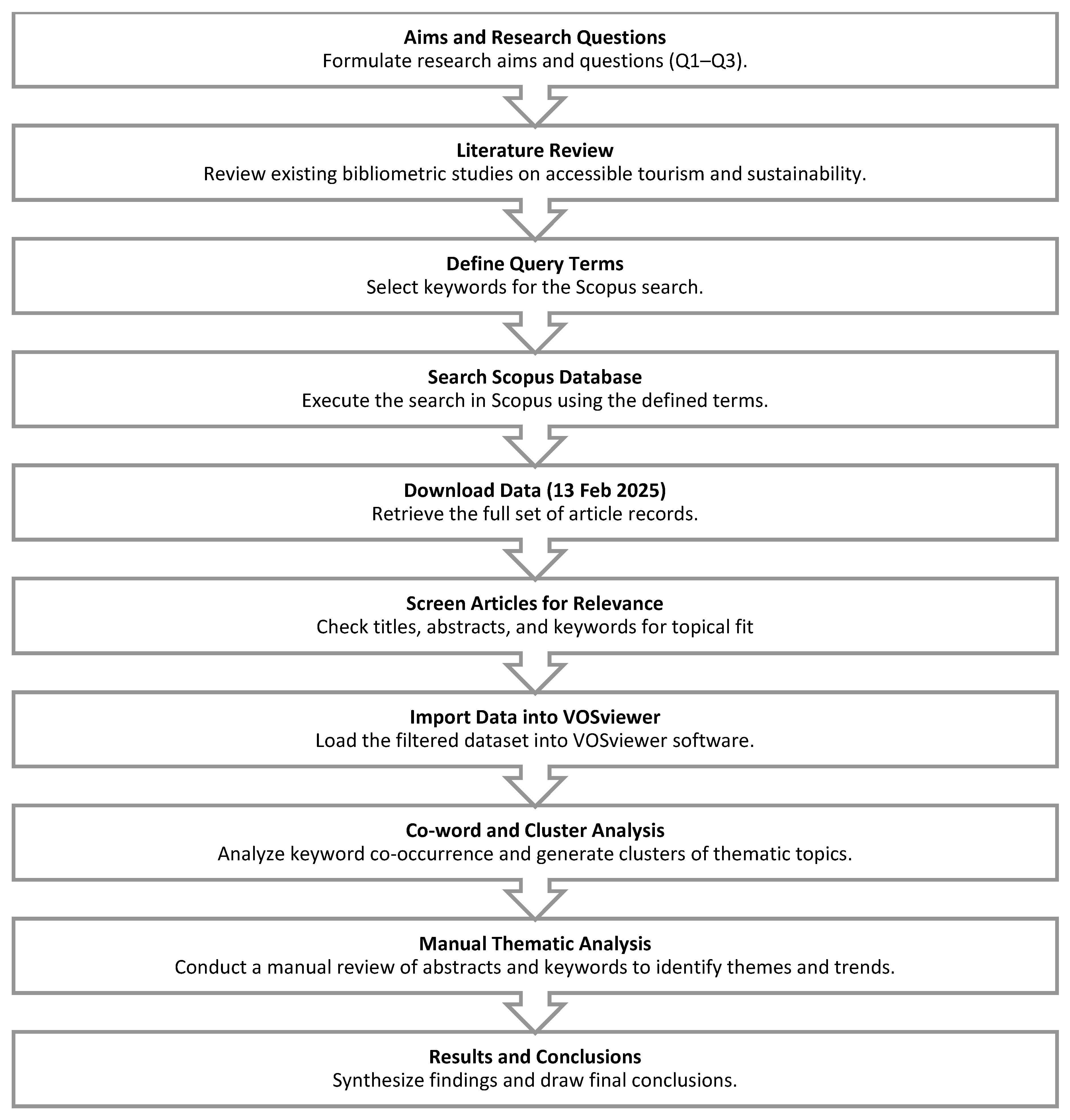

The methodological steps are illustrated in the

Figure 1 flowchart below and will be explained in detail in the sections that follow.

The research method used in this study involves a systematic thematic analysis of abstracts and themes from a curated selection of research articles. This qualitative approach is based on the direct engagement of researchers with texts, where they read, interpret and categorise key topics without the use of automated tools. By manually grouping themes, identifying conceptual connections and recognising emerging trends, this method provides a nuanced synthesis of knowledge from multiple sources. The analysis allows for the identification of dominant research areas and their connections, providing insight into broader academic discourse on the topic. An additional method used in this work was the analysis of authors’ keywords, which has become an important technique for mapping the intellectual framework of research areas. By examining the co-occurrence of keywords, co-word analysis uncovers connections between topics and tracks the progress of scientific development [

32].

The analysis included articles combining terms related to accessible tourism and sustainable development found in the Scopus Database using the following criteria: “sustainable development” OR “sustainable tourism” OR “sustainability” AND “inclusive tourism” OR “accessible tourism” OR “social tourism” OR “tourism for all” OR “tourism without barriers” OR “integrative tourism” or “universal tourism”—searching in abstracts, titles and keywords.

Scopus, as one of the largest and most prestigious bibliometric databases, provides valuable data for scientific analyses. With its extensive subject coverage, high-quality indexed sources and advanced citation metrics, research based on this database enables reliable assessment of scientific impact, identification of research trends and analysis of international academic collaboration [

33]. The choice of a single database—rather than merging data from multiple sources—is methodologically justified. It also eliminates the risk of data duplication and metadata inconsistencies that may arise when combining information from different platforms [

34].

The study was conducted in February 2025, and the dataset was downloaded on 13 February 2025. The final sample included 200 articles: 192 in English, 4 in Spanish, 1 in Ukrainian, 1 in Portuguese, 1 in German, and 1 in French. However, all articles included English-language titles, abstracts and keywords, which allowed for consistent analysis and ensured comparability across the dataset. All retrieved records were then screened for topical consistency with the study’s scope, and none were excluded, as each article proved relevant to the defined subjects.

The results selected from the database were entered into the VOSviewer programme to analyse the links of the obtained literature list for a given topic area. The software was used to observe the dependencies and relationships between the authors’ keywords. The analysis used the relationships between the co-occurrence links among the terms, which resulted in a map of the network of links, and also grouped the keywords into clusters showing the thematic coherence of related works. The clustering process in VOSviewer is based on a similarity measure known as association strength, which quantifies the relatedness between two items based on their co-occurrence patterns.

The similarity s

(ij) between two items i and j is calculated using the following formula:

where c

(ij) represents the number of co-occurrences of items i and j, and w

i and w

j refer to the total number of occurrences (or total co-occurrences) of each item. This metric is proportional to the ratio of the observed number of co-occurrences to the expected number under the assumption of statistical independence between the items. Once similarity values are calculated for all item pairs, VOSviewer uses a layout and clustering algorithm to place and group items in a two-dimensional space, with shorter distances and common cluster membership indicating higher similarity [

35].

4. Results

A total of 200 articles were analysed. The types of publications are shown in

Table 2. The largest group included articles from scientific journals.

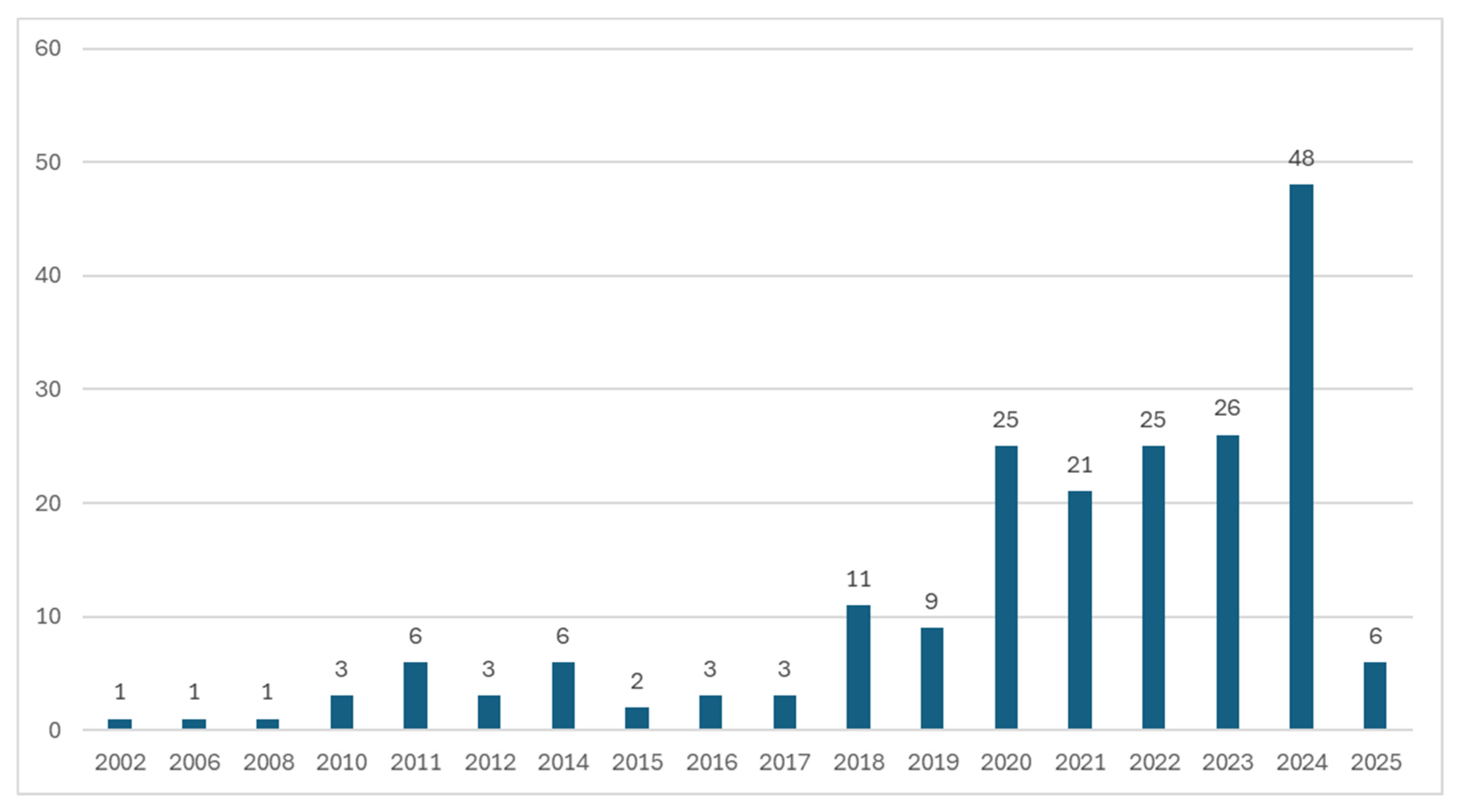

Although sustainable development theories include inclusivity as one of their key objectives, these terms have been explicitly linked in scholarly research only since 2002 (

Figure 2). A significant increase in the number of publications has been observed since 2020, with a particularly notable surge in academic output on this topic in 2024. In comparison, searching for the phrases “sustainable development” OR “sustainable tourism” OR “sustainability” in the Scopus database alone yielded over 763,000 documents published since the 1970s, and the phrases “inclusive tourism” OR “accessible tourism” OR “social tourism” OR “tourism for all” OR “tourism without barriers” OR “integrative tourism” or “universal tourism” yielded 964 documents, the oldest of which was published in 1953.

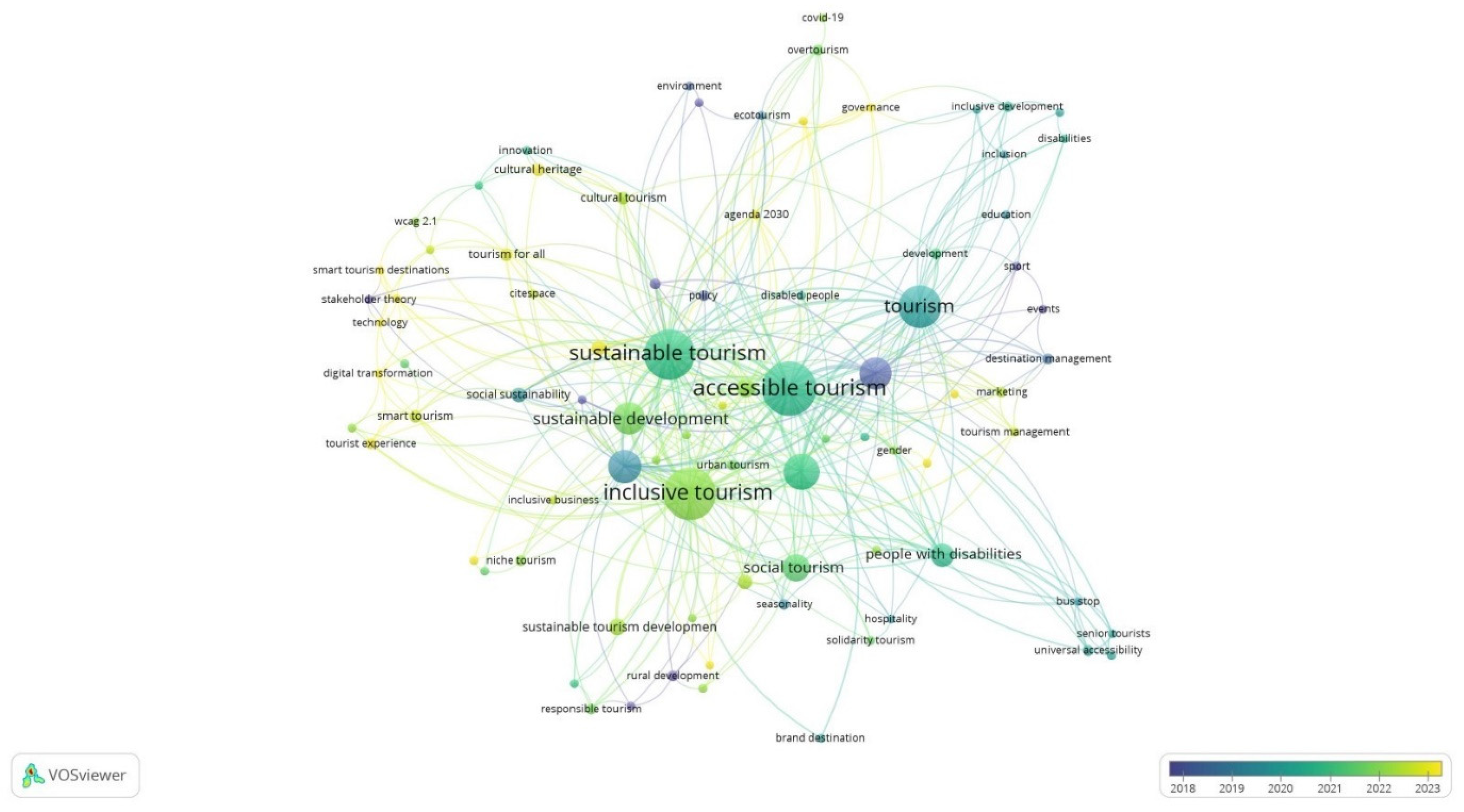

In

Figure 3, the keywords are shown as well as the relationships between them that emerged over the years in which the analysed articles were published. The keywords that appeared the earliest (in the years 2010–2018) include: accommodation, stakeholder theory, environmental management, tourism planning, universal design, events, sport, rural development. Whereas the keywords from articles recently published, i.e., in the years 2023–2025, are: tourism development, inclusive, smart tourism destinations, technology, tourist experience, digital transformation, visitor experience, Agenda 2030, co-creation.

The evolution of keywords over time reflects the changing research priorities in the field of tourism studies. In the 2010–2018 period, early studies were mainly focused on basic aspects, emphasising the structural and strategic dimensions of tourism development. In addition, topics such as events, sports and rural development highlighted the role of tourism in regional development and community engagement. In contrast, more recent studies (2023–2025) demonstrate a shift in research interests towards innovation, digitalisation and inclusiveness in tourism. Furthermore, the inclusion of the 2030 Agenda and co-creation suggests increasing emphasis on sustainable development, participatory approaches and global policy frameworks in tourism studies.

In VOSviewer, we extracted all author keywords from the dataset and applied a minimum occurrence threshold of three—meaning each term had to appear in at least three different articles to be included. This filter reduced the influence of one-off or highly idiosyncratic keywords, ensuring that only consistently used concepts—those truly representative of the field—were mapped. As a result, 85 keywords met this threshold and were analysed for co-occurrence; their network of connections is shown in

Figure 3. By choosing three occurrences as our cutoff, we strike a balance between capturing emerging themes and avoiding the noise introduced by very rare terms. Among the author keywords from the database of articles analysed in this study, which overlap with those from the SCOPUS search algorithm, the most frequently appearing terms in the network created by VOSviewer were as follows:

Accessible tourism—41 occurrences;

Inclusive tourism—39 occurrences;

Sustainable tourism—37 occurrences;

Sustainability—18 occurrences;

Sustainable development—17 occurrences;

Social tourism—13 occurrences;

Tourism for all—4 occurrences.

However, the terms “tourism without barriers”, “integrative tourism” and “universal tourism” did not appear in the network at all.

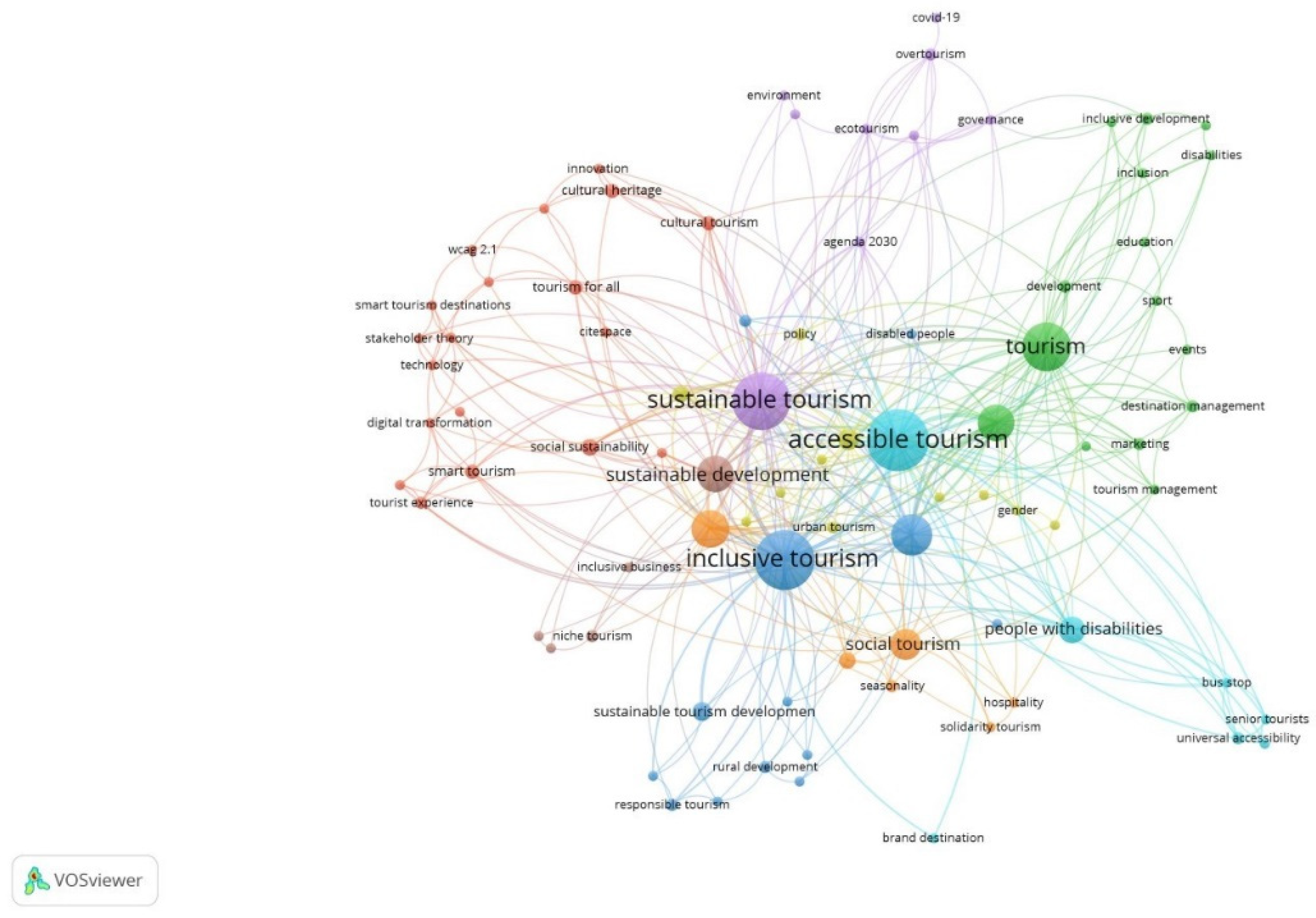

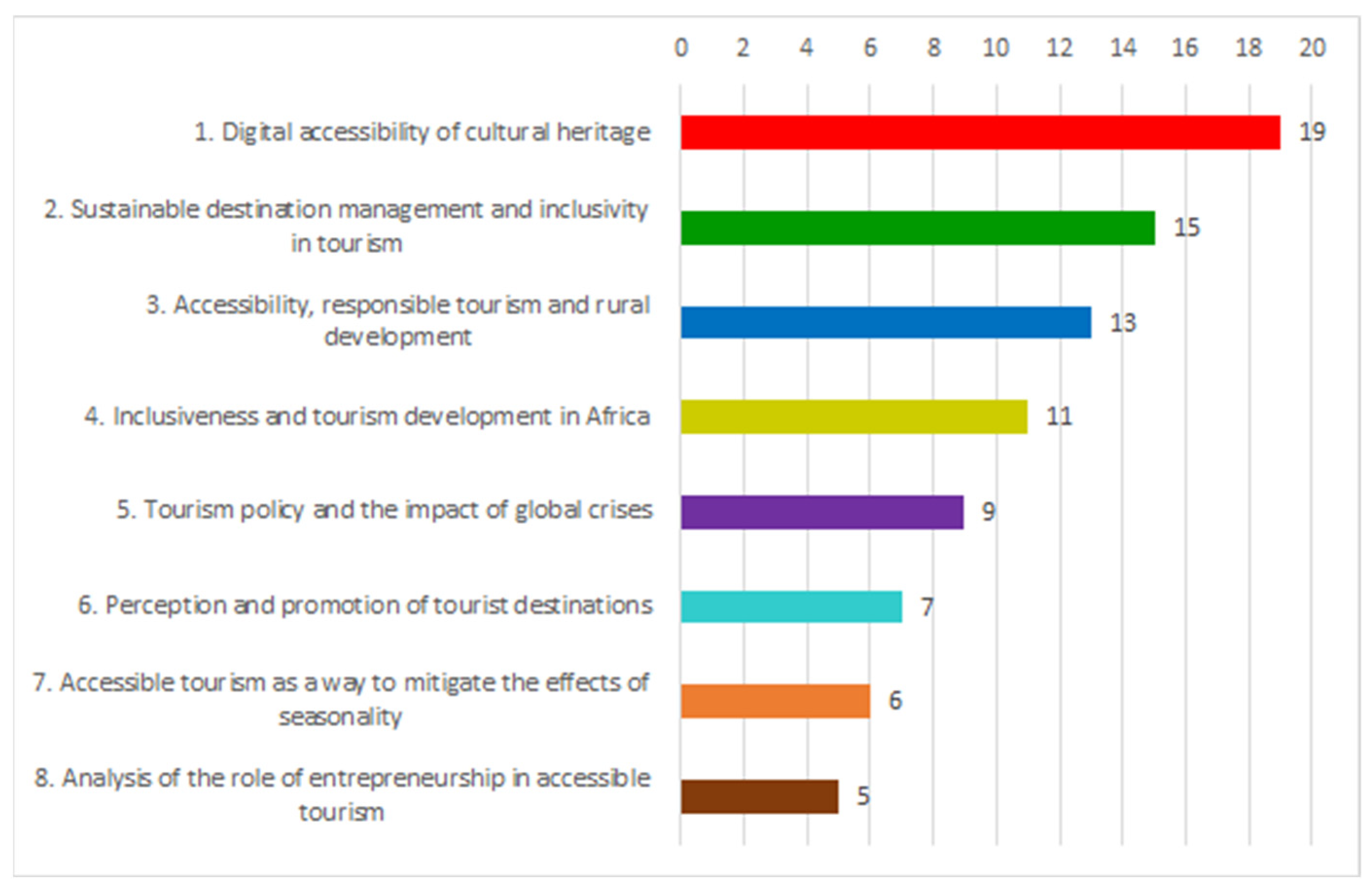

In VOSviewer, the software also grouped the keywords into clusters. The clustering process in the VOSviewer is based on a weighted and iterative algorithm that identifies groups of related terms within the network. For the 85 analysed keywords, clusters were formed under the assumption that each cluster within the network consists of at least five keywords. The clustering algorithm in the VOSviewer works by detecting patterns of co-occurrence between keywords, ensuring that closely related terms are grouped together. This helps to reveal thematic structures within the dataset, making it easier to identify major research trends and interconnections between concepts. The resulting clusters highlight different thematic areas in the analysed body of literature, facilitating a deeper understanding of how specific topics relate to one another [

33]. As a result of the clustering process in VOSviewer, eight clusters were formed. Their specific thematic focus and the colour scheme corresponding to those themes (as introduced in

Figure 4) are detailed in

Figure 5 which illustrates the colour coding used to identify each cluster within the overall network. A comprehensive list of all keywords included in each cluster is presented in

Table 3.

4.1. Cluster 1 (19 Items): Digital Accessibility of Cultural Heritage

Author keywords: accommodation, citespace, cultural heritage, cultural tourism, digital accessibility, digital transformation, experience design, global south, innovation, mobile applications, smart tourism, smart tourism destinations, social sustainability, stakeholder theory, technology, tourism for all, tourist experience, visitor experience, WCAG 2.1.

The review of topics and summaries of the analysed literature underlines the transformative impact of modern technologies on tourism, especially in the context of smart tourism. Researchers emphasise that sustainable smart tourism integrates digital solutions to improve both visitor experience and environmental responsibility. In research, it has been widely discussed as to how artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR) can contribute to increasing the accessibility of tourism experiences, effectively reducing physical barriers [

36]. However, these remain isolated examples, and the topic is still at an early stage of development in the literature. Isolated studies also point out that mobile applications play a key role in improving the accessibility of tourism services, offering personalised recommendations, e.g., regarding the selection of tourist routes and real-time assistance [

37]. There is a growing body of research—currently accounting for approximately 5% of the analysed articles—focused on inclusive and accessible tourism information delivery. Both the method of communication and the informational value provided to diverse tourist groups (including individuals with disabilities) are examined in these studies. A significant area of analysis involves the accessibility of tourism websites, particularly in accordance with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1.) Researchers assess how well tourism-related digital platforms accommodate users with visual, auditory, cognitive and motor impairments, ensuring equitable access to travel planning resources. Additionally, best practices are explored for designing inclusive tourism communication strategies that enhance user experience and promote universal accessibility [

38].

The importance of providing a barrier-free digital environment has also been a recurring theme in recent studies, emphasising the need for inclusive digital infrastructures. In current analyses, the potential is emphasised of virtual tourism and the metaverse in extending tourism beyond physical limitations, offering immersive experiences that can complement or even replace traditional travel. However empirical studies exploring these possibilities are still relatively scarce [

39]. In addition, authors highlight that AI, big data and algorithms have the potential to support the development of sustainable tourism, ensuring that the industry’s growth is aligned with environmental and social priorities, while meeting the diverse needs of stakeholders. According to some studies, the development of intelligent information systems represents a significant advancement in tourism management, providing new models for providing real-time data and improving traveller decision-making processes. Researchers also underline the growing role of digital entrepreneurship, noting how technology-based solutions allow businesses to respond more effectively to changing market requirements [

40].

4.2. Cluster 2 (15 Items): Sustainable Destination Management and Inclusivity in Tourism

Author keywords: co-creation, destination management, development, disabilities, disability, education, events, inclusion, inclusive development, marketing, SDGs, sport, tourism, tourism management, tourist destination.

Analysis of the reviewed literature highlights the growing importance of co-creation, destination management and development of inclusive tourism as key factors shaping contemporary tourism and event planning. This thematic area represents the largest proportion of the analysed studies, accounting for approximately 20% of the total. Research in this area allows to underscore the importance of integrating accessibility, sustainability and innovation in tourism strategies in order to increase destination competitiveness and promote social inclusion. Co-creation is identified as a driver of innovation in tourism and education, shifting from provider-centric models to user-driven engagement [

41]. In research, it is suggested that collaborative approaches, supported by technology and stakeholder involvement, enhance visitor experiences, foster sustainable development and align tourism strategies with SDGs [

16,

42]. Inclusive marketing strategies that leverage technology, mobile applications and AI-driven personalisation can further strengthen destination competitiveness, while ensuring socially responsible tourism growth. In studies on event management, it is highlighted that festivals and sports events, including parasport, play a crucial role in destination branding and competitiveness. Despite the growing interest in accessible tourism, the social legacy of disability sports events remains underexplored in tourism literature. Findings suggest that parasport can significantly enhance destination accessibility, making it more attractive to people with disabilities, families and ageing populations [

43,

44].

4.3. Cluster 3 (13 Items): Accessibility, Responsible Tourism and Rural Development

Author keywords: accessibility, disabled people, inclusive tourism, local communities, mountain tourism, natural protected areas, potential, responsible tourism, rural development, sustainable tourism development, tourism planning, tourists with disabilities, universal design.

Research on rural and nature-based tourism allows to emphasise its crucial role in sustainable tourism development, particularly in protected areas [

45,

46]. In 5% of analysed publications, various forms of tourism accentuated, including adventure tourism, national park tourism eco-tourism, and nature-based tourism, which are key in balancing economic growth and environmental conservation. Additionally, inclusive tourism and universal design are essential for improving accessibility in rural and green destinations, ensuring that tourists with disabilities and local communities can benefit from responsible tourism practices [

43]. In some publications, usually as case studies, projects are discussed for the development of accessible, innovative forms of tourism such as glamping, creative tourism, last-chance tourism, birdwatching, geotourism or geo-catching as particularly important for sustainable and inclusive tourism planning. These projects constitute about 3% of the reviewed corpus [

47,

48].

4.4. Cluster 4 (11 Items): Inclusiveness and Tourism Development in Africa

Author keywords: Africa, community-based tourism, gender, inclusive, inclusive tourism development, policy, regenerative tourism, sustainable development goals, tourism development, urban tourism, Zimbabwe.

The keywords in this cluster are interconnected in several ways that highlight the challenges and opportunities present in the region. Approximately 5% of the reviewed publications specifically focus on tourism development in African contexts. In many African countries, political instability poses significant obstacles to effective tourism development. Document analysis shows that in Sub-Saharan African cities, tourism is largely influenced by neoliberal development strategies. These approaches often compromise sustainable tourism practices because they tend to prioritise economic growth over social and environmental considerations [

49,

50].

The discourse on sustainable tourism development accentuates the need for strong governance and robust sustainable development institutions. These institutions are essential for establishing regulatory frameworks that support local engagement and the empowerment of marginalised groups, such as people with disabilities and women. Inclusive tourism policies can significantly contribute to promoting gender equality and ensure that tourism development is aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, in some publications, it has been underlined that while there are challenges in implementing inclusive tourism development in Africa, particularly in relation to gender and disability, there is significant opportunity for policy innovation and community engagement. By focusing on inclusiveness and collaboration, tourism can become a tool for sustainable development and empowerment across the continent [

51].

4.5. Cluster 5 (9 Items): Tourism Policy and the Impact of Global Crises

Author keywords: Agenda 2030, COVID-19, ecotourism, environment, environmental management, governance, overtourism, participatory planning, sustainable tourism.

The keyword cluster reflects the growing need to cope with crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, while rebuilding tourism in a sustainable and resilient way. Approximately 3% of the analysed publications address tourism in the context of crisis and post-crisis recovery. Analysis of the themes and abstracts shows that, according to the authors of some publications, crises pose both challenges and opportunities [

52,

53]. The COVID-19 pandemic confirmed a trend that began in 2001, marking a change in the perception of hospitality in Western societies, particularly due to overtourism. However, such disruptions can accelerate the transition to more sustainable tourism models, strengthening regenerative tourism as a response to post-crisis recovery. In selected publications, the importance of such an approach is noted, as it not only restores but also strengthens destinations for the future by promoting environmental protection, community engagement and long-term resilience [

54].

4.6. Cluster 6 (7 Items): Perception and Promotion of Tourist Destinations

Author keywords: accessible tourism, brand destination, bus stop, people with disabilities, perceptions, senior tourists, universal accessibility.

Analysis of the topics and abstracts of the examined articles confirms the existence of such a cluster. Accessible tourism research highlights the importance of universal accessibility in shaping the destination brand and promoting inclusive urban environments. Two articles feature research in which it is noted that bus stops, as key elements of public transport infrastructure, need to be accessible to disabled and elderly visitors through barrier-free spaces, tactile pavements, appropriate lighting and rest areas. Projects such as ACCES4ALL demonstrate the need for perception-based planning, where tourists’ opinions inform the development of age-friendly and inclusive transport systems [

52]. While universal design increases mobility and social inclusion, the results indicate that some technological features (e.g., QR codes, NFC) are perceived as less important by senior visitors. Integrating accessible urban infrastructure strengthens the competitiveness of the destination, reinforcing the role of universal accessibility in positioning cities as attractive and inclusive for all visitors [

55].

4.7. Cluster 7 (6 Items): Accessible Tourism as a Way to Mitigate the Effects of Seasonality/Fluctuations in Tourist Traffic

Author keywords: hospitality, seasonality, social tourism, solidarity tourism, sustainability, tourism policy.

In reviewed publications, the role is emphasised of accessible tourism in mitigating the effects of seasonality, ensuring year-round economic stability and inclusiveness [

56]. However, it should be noted that this topic is addressed only in isolated studies. Furthermore, tourism is a powerful driver of sustainable development, shaping territorial and environmental change, while supporting the social well-being of present and future generations [

57]. It serves as a bridge between economic growth, cultural and landscape protection and global values, such as peace, tolerance and intercultural dialogue. Effective governance and participatory planning are essential to counteract overtourism and ensure that tourism benefits local communities. By integrating sustainable development principles into tourism policies, stakeholders can create a balance between economic development and the protection of natural and cultural heritage. In line with the 2030 Agenda, this vision reinforces the role of tourism as a transformative force for a more just and ecologically responsible future [

58].

4.8. Cluster 8 (5 Items): Analysis of the Role of Entrepreneurship in Accessible Tourism

Author keywords: entrepreneurship, inclusive business, network, niche tourism, sustainable development.

The cluster generated by VOSviewer, verified through the analysis of abstracts and themes of the surveyed articles, underscores the intersection of entrepreneurship, inclusive business, networks, niche tourism and sustainable development in the tourism sector. A variety of tourism entrepreneurs are explored in the research within this cluster, including travel agencies, tour operators, hotels, museums, mountain huts, eco-farms and catering enterprises, emphasising their role in promoting sustainable tourism development [

59,

60,

61]. Each of these topics was represented by one to three publications. Social tourism enterprises and cross-border cooperation aimed at increasing the accessibility of tourism businesses are also examined [

62]. Furthermore, the results indicate that inclusive tourism organisations and stakeholders involved in heritage preservation and cultural tourism contribute to the expansion of niche tourism markets, reinforcing the significance of entrepreneurial networks in promoting sustainability and inclusiveness in the industry [

63].

4.9. Other Results from the Analysis of Topics and Abstracts

Studies on sustainable tourism development policy were the most numerous in the study group. In them, the problem was often presented on the basis of a case study on the development of a tourist destination or organisation. In several cases, the authors deliberated theoretical considerations and proposed development models based on document research or bibliometric analyses, e.g., [

20,

64].

Numerous studies have been focused on the development of inclusive tourism in a sustainable manner, with particular emphasis on Portugal and Spain. Following research on these countries, the state of inclusive tourism in African countries has been increasingly examined, e.g., [

48,

65].

The largest number of studies in the field of accessible and inclusive tourism regard people with mobility disabilities [

66]. In a slightly smaller but still significant number of studies, their authors examine the needs of older travellers, and individual studies concern groups such as people with dementia and autism [

67,

68]. In addition, increasing attention is being paid to travellers with special dietary requirements, whether due to health conditions or religious practices, such as halal tourism. These themes, however, are represented by only a few studies. A slightly larger, though still limited, number of publications (approximately 3%) involve the inclusion of women in the development of tourism, but researchers also emphasise the need to include other marginalised groups in tourism planning, such as people from the LGBTQ+ group [

69].

5. Discussion

The body of scholarly work combining inclusive tourism (or related terms) and sustainable development remains relatively limited. In contrast, bibliometric analyses focusing solely on sustainable tourism in the Scopus database have shown a significantly higher volume of publications, even when considering only the top 10 contributing journals and covering the period up to 2022 [

20]. This highlights the disparity in research output and underscores the need for further exploration at the intersection of these two fields.

In the study, an increase was found in publications linking inclusive tourism and its synonyms to sustainable development after the pandemic, reflecting a broader trend of regenerative tourism—a revival of tourism that not only restores pre-pandemic conditions but instead prioritises sustainability and inclusiveness. This pattern has also been observed by other researchers; however, the literature suggests that the strength of this association may depend on context. For example, Topaçoğlu and Uygur [

70] noted an increase in publications on disability and tourism in Turkish journals between 2005 and 2023.Although sustainability-related concepts were mentioned, their explicit link to sustainable development was only present in a limited number of studies.

The lack of co-occurrence between terms such as “tourism without barriers”, “integrative tourism” and “universal tourism” with keywords related to sustainable development may suggest that these concepts are either outdated, marginal in academic discourse, or insufficiently integrated into the dominant research streams. While these terms refer to similar or overlapping ideas as inclusive tourism, they appear less frequently in the literature—possibly due to the lack of standardised usage and their weaker alignment with widely accepted terminology. In the present study, dominance of the term “accessible tourism” was confirmed, aligning with the findings of Leiras and Caamaño-Franco [

29]. This term appears more often than “inclusive tourism” in relation to the topic of sustainable development. In Leiras and Caamaño-Franco’s research, the authors highlight the evolution of terminology related to accessible tourism, showing how different terms have been used across time, regions and academic contexts. They also emphasise the global spread of the concept. Similarly, in the current analysis, we revealed the prevalence of “Accessible Tourism” over other synonymous terms, while some related concepts did not appear at all in the examined network. This suggests ongoing discrepancies in the use of terminology within academic discourse, confirming that, as Leiras and Caamaño-Franco [

29] observed, the field lacks full standardisation in its key vocabulary.

Tourism is a social phenomenon that is part of sustainable development. Therefore, the importance of inclusion is indisputable, which is supported by bibliometric research showing significant links between the concepts of inclusive tourism (or related terms) and sustainable development. Inclusive tourism is becoming more and more important and its significance is increasingly indicated in the context of the global approach to tourism. By building a more inclusive and understandable society, it creates a more open and sustainable tourism sector.

In the academic literature, a conceptual misunderstanding occasionally arises, linking inclusive tourism with the “all-inclusive” model—travel arrangements in which tourists prepay for a comprehensive package that includes transportation, accommodation, meals, and organised tours. In reality, all-inclusive tourism often runs counter to the fundamental objectives of inclusive tourism. Over recent decades, sociological analyses have shown that all-inclusive resorts tend to form spatial and economic enclaves inaccessible to local populations, thereby restricting opportunities for local entrepreneurs to engage in and benefit from the tourism value chain. Furthermore, such models typically divert tourism-generated revenues to multinational hotel corporations and foreign travel intermediaries, rather than fostering local socio-economic development [

71,

72,

73,

74]. Tourist enclaves created by all-inclusive products may, in practice, become all-exclusive spaces, effectively marginalising local communities in developing destinations [

75,

76]. Tourism is often regarded as a sector with significant potential to foster inclusive business models, offering employment and income opportunities across an extensive value chain [

4,

77].

The first research question was focused on identifying the most frequently studied themes in the literature on accessible tourism and sustainability. The predominant theme in the analysed literature is destination management in the context of sustainable development and inclusive tourism (or related terms), with particular focus on exploring various models, methodologies and approaches. The topic was largely explored through case studies, providing in-depth insights into practical applications and contextual nuances of sustainable development and inclusive tourism in destination management. Many of these studies were specifically focused on African countries, shedding light on the unique challenges and opportunities related to sustainable development and inclusive tourism within this regional context. The data from the bibliometric analysis conducted by Ateş, Sunar and Kurt [

78] on sustainable tourism and its connection to destination management allows to confirm the increasing interest in these topics in recent years. Their findings highlight the growing focus on sustainability in tourism practices and the management of tourist destinations. The second most frequently addressed theme was the development of tourism with the inclusion of local communities. Within these studies, some of their authors underlined the significance of women in tourism development, while a few mentioned other marginalised groups, such as LGBTQ+ communities. Studies are beginning to emerge in which the impact of tourism on local environments from a gender perspective is being examined, as highlighted by Abellan Calvet et al. [

79]. Their research based on bibliometric methodology allows to reveal that tourism affects women and men differently, particularly in areas such as natural resource management, social dynamics and labour markets. For example, women are often more impacted by water scarcity due to tourism, and gender roles influence participation in tourism-related activities as well as job opportunities. However, such studies remain scarce, and in not all of them are these issues addressed within the broader context of inclusivity and sustainable development. The need for further research on LGBTQ+ communities in tourism is also recognised by Ong et al. [

80], who highlight the limited scope of existing studies. Their findings point to strong focus on critical perspectives, while practical insights into LGBTQ+ travel behaviours and experiences remain underexplored. The authors emphasise the importance of understanding these travellers’ needs to create safer, more inclusive tourism experiences, aligning with broader sustainability goals.

The second research question aimed to uncover the gaps in current research on accessible tourism that need to be addressed to enhance understanding and practice. One significant gap is the underrepresentation of certain marginalised groups. While much of the existing literature is focused on individuals with mobility impairments, little attention has been paid to communities such as those with cognitive disabilities, people living with dementia or individuals with special dietary requirements. In studies, policy recommendations are often highlighted, but there is a lack of research into the practical challenges of implementing these policies in diverse socio-economic contexts. This is particularly evident when it comes to rebuilding and revitalising tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic. Although many articles offer guidelines on how to approach this recovery, there is still a noticeable gap in examining the actual processes and outcomes of these efforts. Additionally, a research gap identified in the present analysis is the limited focus on ecotourism within the context of inclusive tourism. Inclusive tourism should align with ecotourism principles, encouraging tourists to be mindful of their environmental impact. Other bibliometric analyses on sustainable tourism, such as the study by Kumar et al. [

24], have allowed to emphasise the importance of integrating sustainable practices to minimise negative environmental impacts and promote responsible travel. However, this theme was notably absent in the publications combining inclusive and sustainable tourism that were examined by the authors of this study. Furthermore, no studies were found in which the growing influence of media in raising awareness about inclusive tourism would be examined within the broader context of sustainable development. This is particularly noteworthy given that, as highlighted by Agarwal et al., the expansion of global media, in the example of through over-the-top (OTT) platforms, has the potential to reach audiences worldwide, shaping perceptions and promoting more inclusive tourism practices [

21].

The third research question investigated the emerging trends in recent studies on inclusive tourism (or related terms) and its relationship with sustainability. Several key developments have been identified, reflecting a broader shift towards more inclusive, technology-driven and socially responsible tourism practices. There is a growing focus on technological integration, with the use of AI, big data, and mobile applications to enhance accessibility and sustainable practices. Digital accessibility has gained attention, particularly in ensuring tourism websites comply with standards such as WCAG 2.1. Virtual tourism and the metaverse are also being explored as complementary experiences, offering accessible alternatives to physical travel. The findings from the current analysis align closely with the results of the bibliometric study conducted by El Archi et al. [

81], in which the authors highlight the increasing integration of digital technologies in promoting sustainable practices within tourism, particularly through the use of smart tourism tools and big data to enhance destination management. Additionally, the role of inclusive entrepreneurship is increasingly recognised, with business practices and entrepreneurial networks supporting sustainable tourism. Researchers are expanding their focus on diverse tourist needs, addressing groups such as senior travellers, individuals with special dietary requirements and other marginalised communities. Finally, there is rising interest in crisis-driven adaptations, particularly in using tourism as a tool for resilience and regeneration post-crisis, with participatory approaches and governance promoting long-term sustainability. These trends reflect a broader shift towards more inclusive, technology-driven and socially responsible tourism practices.

6. Conclusions

The connection between the theme of sustainable development and inclusive tourism has emerged relatively recently. As a result, the number of academic publications on this subject remains limited. However, this topic is gaining increasing attention as an evolving research trend, reflecting the growing recognition of the need for more accessible and responsible tourism practices within the framework of sustainability.

The post-pandemic period has seen a noticeable increase in publications addressing the reconstruction of tourism in a sustainable way. Concepts such as regenerative tourism and initiatives aligned with Agenda 2030 have gained traction, emphasising the need for a more responsible and inclusive approach to tourism development.

Given the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), future research should extend beyond traditional areas of accessible tourism, which are often focused on travellers with disabilities or the inclusion of local communities in tourism development programmes. The need to explore other marginalised groups and address broader aspects of inclusivity is growing. This concerns, e.g., gender equality and social equity in tourism.

In recent studies, a link has been made between inclusive tourism and the “smart tourism” concept, highlighting the role of digital innovation and data-driven solutions in making tourism more accessible and equitable.

Moreover, in numerous trials, their authors underscore the importance of collaboration among all stakeholders in the sustainable development of tourism. A multi-sectoral approach, involving governments, businesses, local communities and travellers, is essential to ensure that tourism growth aligns with sustainability principles while fostering inclusivity on multiple levels. This is indicated by the recently published results of research on the accessibility of tourist attractions in historical cities inscribed on the UNESCO list, such as Krakow in Poland [

82], Jedah in Saudi Arabia [

83]. In the relatively underdeveloped Świętokrzyskie region (Poland), creating accessibility to tourist attractions for people with disabilities can bring economic benefits and also improve the perception of the region as a modern and inclusive place, ready to welcome all visitors, regardless of their disability [

84].

The adaptation of tourist attractions often encounters objective obstacles, which forces the use of innovative and unconventional solutions. Effective inclusivity involves adapting communication—channels, formats and tools—to people struggling with various accessibility barriers. Investment in modern technology is important for creating immersive and innovative cultural experiences [

85].

The analysed works provide indications for the practice of creating accessible tourism. The authors of the above-mentioned publications suggest the need to define minimum requirements for all tourist attractions (separate for buildings and for open spaces) that will allow for the service of people with physical and intellectual disabilities. In their opinion, it is also necessary to create a subsidy system for attractions with lower tourist traffic or located in historic buildings.

With regard to the competences of staff serving people with disabilities, there are postulates to introduce relevant specialisation’s, as well as postgraduate studies and certified training into the curricula of tourism faculties.

It is necessary to use new technologies in accessible tourism, both to remove physical barriers and to improve information activities and as a tool for sharing the tourist experience through the use of solutions such as augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR).

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

The study acknowledges several limitations—most notably the use of only Scopus resources, a limited reference scope, and the application of specific search terms—which may serve as a basis for future research. Further investigations could validate and extend these findings through data drawn from other academic databases, including Web of Science, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate.

One limitation of this study is the reliance on author-assigned keywords, which may be subject to a degree of subjectivity. Each author selects keywords based on their own perspective, which can lead to variability in terminology and thematic classification. Additionally, the number of keywords an author can assign is often restricted by the guidelines of the respective journal, potentially limiting the comprehensiveness of the keyword representation.

Another limitation may be interpretation of the concept of inclusive tourism, which has a complex structure, and in the literature, there are many conceptually similar and overlapping terms which cannot be unequivocally treated as synonyms of inclusive tourism.