The Analysis of Cultural Convergence and Maritime Trade Between China and Saudi Arabia: Toda–Yamamoto Granger Causality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

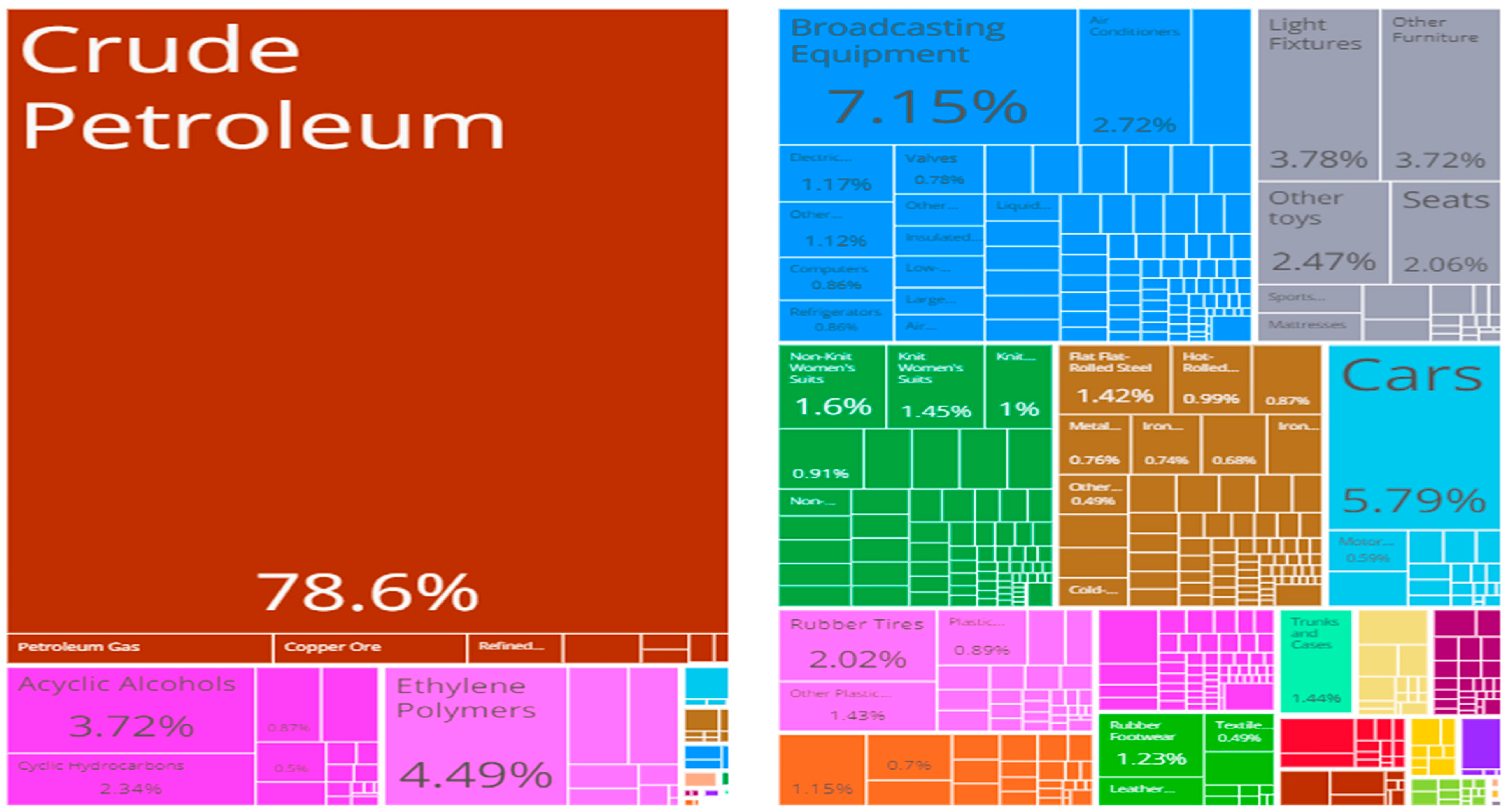

3. China–Saudi Arabia Trade Relationships: An Overview

4. Cultural Convergence and Trade: Dimensions and Drivers

4.1. Trade and Culture Dimensions

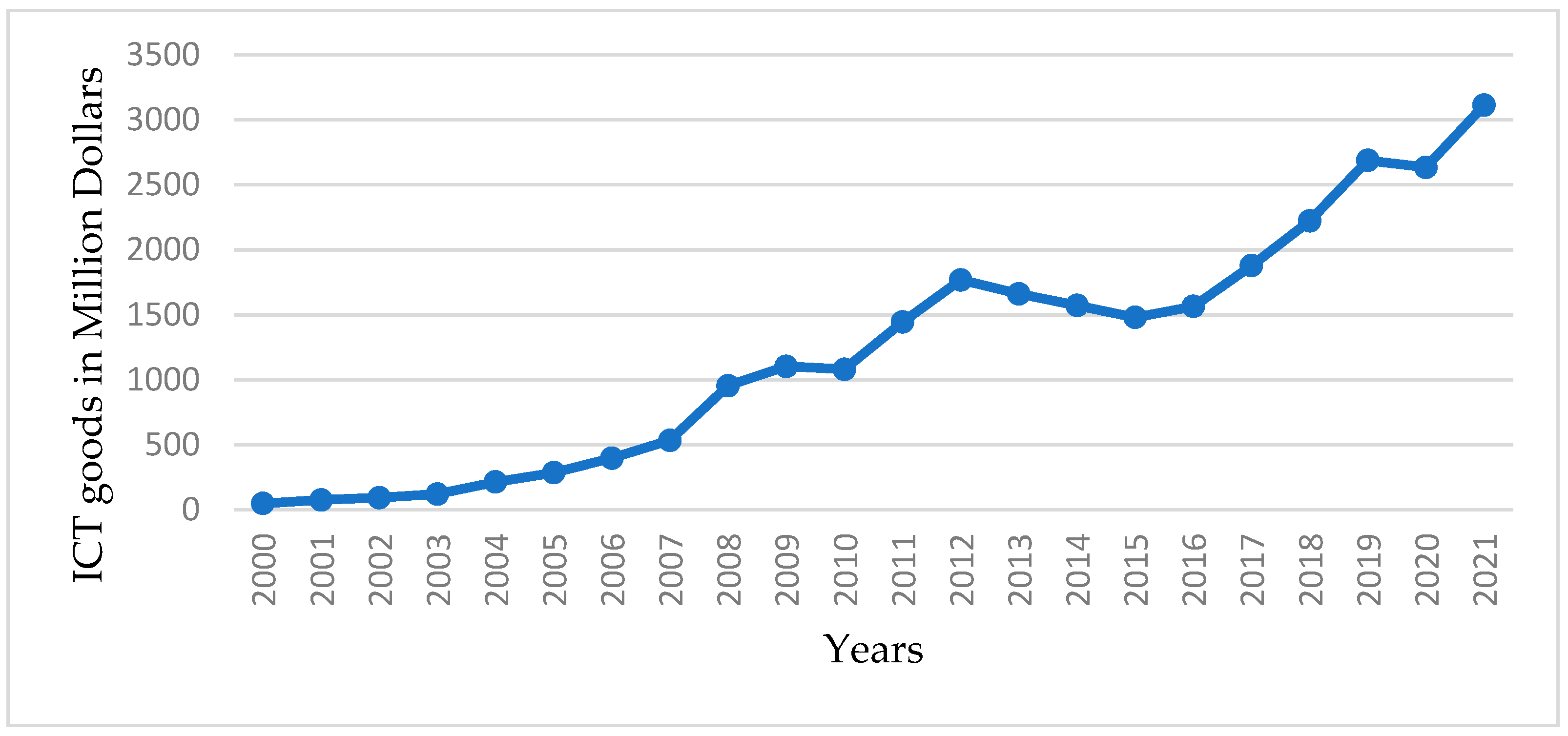

4.2. Creative and ICT Goods Trade as Drivers of Culture Convergence

5. Data and Econometric Methodology

5.1. Data

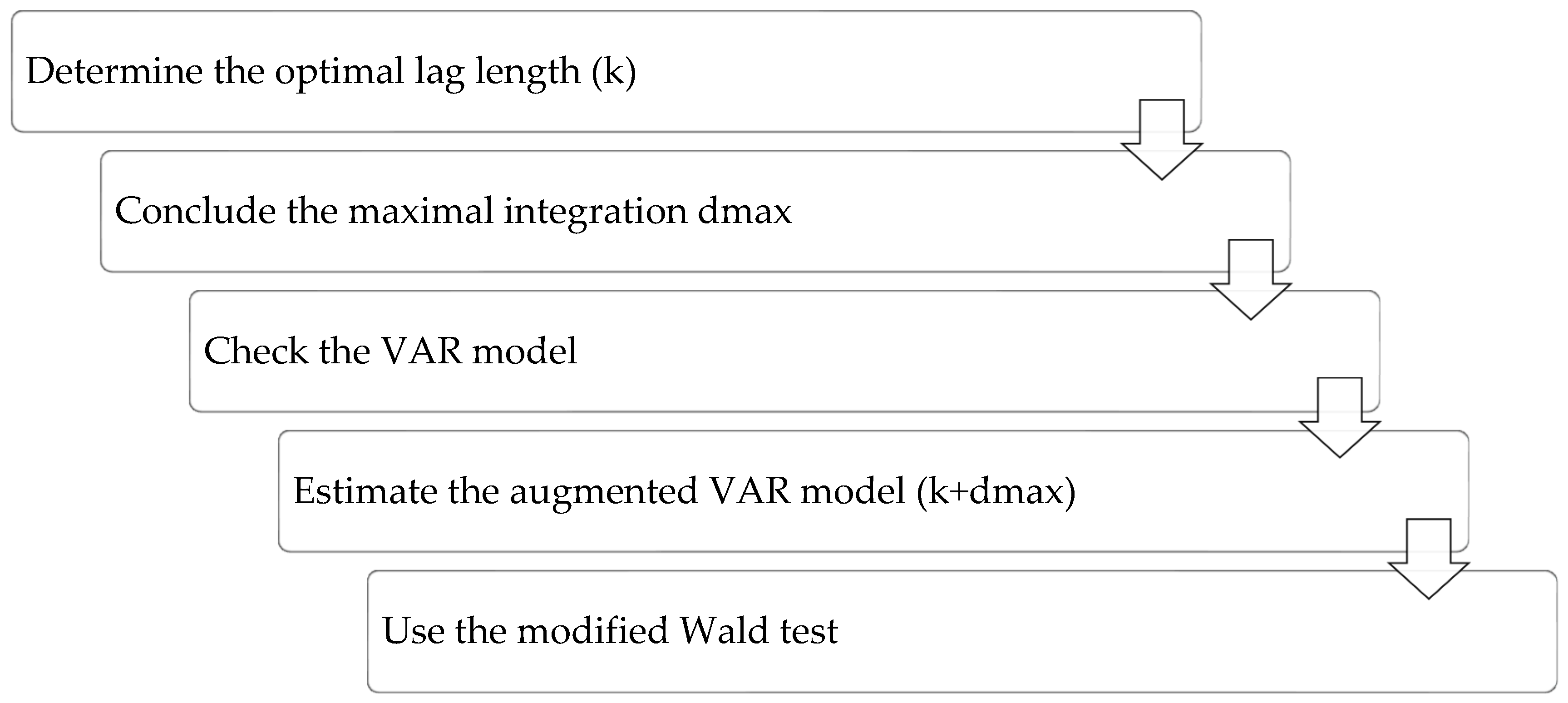

5.2. Methodology

6. Empirical Results and Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Toda–Yamamoto Model: Equations and Explanation

Appendix A.1. Mathematical Formulation

Appendix A.2. Step-by-Step Explanation

- -

- A constant term

- -

- A vector of lagged values (M)

- -

- A residual error term (γit)

Appendix A.3. Definitions of Variables

- MTt—Maritime Trade: Volume or value of maritime trade flows, typically in billions of USD.

- CREt—Creative Economy: Proxy for cultural and creative sectors (e.g., media, arts, advertising), often measured by output or employment in creative industries.

- ICTt—Information and Communication Technology: Indicator reflecting ICT infrastructure or usage, such as internet penetration, ICT exports, or digital readiness.

- POPt—Population: Total population size, included to control for demographic scale effects on trade demand and production.

- γit—Residual term: Captures unexplained shocks in the system not attributed to the included lagged variables.

References

- Zhong, Y.; Inglehart, R.F. China as Number One? The Emerging Values of a Rising Power; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade Development. World Investment Report 2021: Investing in Sustainable Recovery; International Trade Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Degang, S.; Abdrabou, A.A. The Development of China-Arab Cultural Exchanges: Opportunities and Challenges in the Belt & Road Era. BRIQ Belt Road Initiat. Q. 2021, 2, 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, N. The management of cross-cultural virtual teams. Eur. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2022, 6, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, A.; Dyer, J. How Cultures Converge: An Empirical Investigation of Trade and Linguistic Exchange; Department of Economics, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, C.; Maggioni, D. Does international trade favor proximity in cultural beliefs? Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2022, 12, 449–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C.; Harbison, F.H.; Dunlop, J.T.; Myers, C.A. Industrialism and industrial man. Int. Lab. Rev. 1960, 82, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Iapadre, P.L. Cultural products in the international trading system. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 381–409. [Google Scholar]

- Mornah, D.; MacDermott, R. Culture as a determinant of competitive advantage in trade. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. (IJBESAR) 2016, 9, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Si, Y.; Jiang, T. Challenges and countermeasures of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’ in the context of green development. Mar. Dev. 2023, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ktori, M. The Limassol Carnayo: Where Maritime and Intangible Cultural Heritage Converge. IKUWA6 2016, 616–629. [Google Scholar]

- Hiep, T.X.; Binh, N.T. The strait of Malacca (Malaysia) with its role in the network of maritime trade in Asia and East-West cultural exchange in the middle ages. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2020, 17, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cariou, P. Changing Demand for Maritime Trade; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sakita, B.M.; Helgheim, B.I.; Bråthen, S. Drivers, Barriers, and Enablers of Digital Transformation in Maritime Ports Sector: A Review and Aggregate Conceptual Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Transport Systems, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sakyi, D.; Immurana, M. Seaport efficiency and the trade balance in Africa. Marit. Transp. Res. 2021, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesu, E.K.; Sakyi, D.; Baidoo, S.T. The effects of seaport efficiency on trade performance in Africa. Marit. Policy Manag. 2024, 51, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Han, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, D.; Zhang, F. The influence of cultural exchange on international trade: An empirical test of Confucius Institutes based on China and the ‘Belt and Road’ areas. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 34, 1033–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musvver, A. China’s Trade Relations with Saudi Arabia: Performance and Prospects. Int. Aff. Glob. Strategy 2016, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvea, R.; Vora, G. Global trade in creative services: An empirical exploration. Creat. Ind. J. 2016, 9, 66–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorde, T.; Alleyne, A.; Trotman, C. International Trade in Cultural Goods: An Assessment of Caribbean Exports; MPRA: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Li, X.; Shen, A.; Zhou, K. Study on the Impact of 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative and Cultural Distance on China’s Forest Products Trade. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 107, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Lu, C.; Wang, Z. The roles of cultural and institutional distance in international trade: Evidence from China’s trade with the Belt and Road countries. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 61, 101234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Cheng, J.; Wu, Z. Evolution of the cultural trade network in “the Belt and Road” region: Implication for global cultural sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, K.H. An analysis of the effects of cultural, religious, and linguistic differences on international trade. J. East-West Bus. 2024, 30, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, K. The impact of trade liberalization on China–ASEAN trade relations along the belt and road: An augmented gravity model analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 71, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J. Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations; Atlantic Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, Z.; Mohsin, M.; Naeem, M.; Mushtaq, K.; Nazeer, M.A. Pakistan’s Economic and Trade Potential in Regional and Global Power Shifts: A Way Forward. J. Asian Dev. Stud. 2024, 13, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkin, P.; Chen, D.; Ke, J. China’s Energy Investment Through the Lens of the Belt and Road Initiative; King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (“KAPSARC”): Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Review of Maritime Transport 2023: Towards a Green and Just Transition; International Trade Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OEC World. Caricom. 2025. Available online: https://oec.world/en/data-sources/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Gu, B.; Liu, J. A systematic review of resilience in the maritime transport. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2025, 28, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insights, H. Country Comparison Tool; Hofstede Insights: Helsinki, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Han, W. Deepening cooperation between Saudi Arabia and China. King Abdullah Pet. Stud. Res. Cent. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Economic and Social Impact of Cultural and Creative Sectors; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Simoes, A.J.G.; Hidalgo, C.A. The Economic Complexity Observatory: An Analytical Tool for Understanding the Dynamics of Economic Development. In Proceedings of the Scalable Integration of Analytics and Visualization, Papers from the 2011 AAAI Workshop, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Toda, H.Y.; Yamamoto, T. Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J. Econom. 1995, 66, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziramba, E. Wagner’s law: An econometric test for South Africa, 1960–2006. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2008, 76, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Qayum, A.; Zaman, K.-U. Relationship between public expenditure and national income: An empirical investigation of Wagner’s law in case of Pakistan. Acad. Res. Int. 2012, 2, 533. [Google Scholar]

- Chiawa, M.; Torruam, J.; Abur, C. Cointegration and causality analysis of government expenditure and economic growth in Nigeria. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2012, 1, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ayad, H.; Belmokaddem, M. Financial development, trade openness and economic growth in MENA countries: TYDL panel causality approach. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2017, 24, 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Dembure, H.; Ziramba, E. Testing the validity of Wagner’s law in the Namibian context: A Toda-Yamamoto (TY) Granger causality approach, 1991–2013. Botsw. J. Econ. 2016, 14, 52–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, H.O.; Rambaldi, A.N. Monte Carlo evidence on cointegration and causation. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1997, 59, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Trade and Development. Statistics and Data. 2025. Available online: https://unctad.org/statistics (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Rambaldi, A.N.; Doran, H.E. Testing for Granger Non-Casuality in Cointegrated Systems Made Easy; Department of Econometrics, University of New England: Armidale, NSW, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D. Testing for Granger Causality. 2011. Available online: https://davegiles.blogspot.com/2011/04/testing-for-granger-causality.html (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Phillips, P.C.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhan, G. An evaluation of marine economy sustainable development and the ramifications of digital technologies in China coastal regions. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 82, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarala, R.M.; Vaara, E. Cultural differences, convergence, and crossvergence as explanations of knowledge transfer in international acquisitions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1365–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.; Abdulrahman, B.M.A.; Ahmed, S.A.K.; Abdallah, A.E.Y.; Elkarim, S.H.E.H.; Sahal, M.S.G.; Nureldeen, W.; Mobarak, W.; Elshaabany, M.M. The dynamic relationships between oil products consumption and economic growth in Saudi Arabia: Using ARDL cointegration and Toda-Yamamoto Granger causality analysis. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (s) | Purpose | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang. et al. [25] | Examine impact of trade liberalization on China–ASEAN trade under BRI. Analyzed moderating effects of cultural factors (language/religion). | Augmented Gravity Model framework. Analysis of international panel data (2012–2022) China–ASEAN nations. | Increased trade liberalization significantly enhances bilateral trade volumes between China and ASEAN. Shared language and religious beliefs amplify the positive effects of trade liberalization. |

| Liu et al. [22] | Examine the roles of cultural distance and institutional distance in China’s trade relationship with the Belt and Road (B&R) countries | Gravity model using bilateral trade data at product-level during 2002–2016 between China and 99 trading partners. | Cultural distance and institutional distance inhibit China’s bilateral trade with the Belt and Road and cultural exchange driven by the BRI eventually assisting unimpeded trade and deepening the cooperation |

| Chen et al. [23] | Does the cultural trade network contribute to the integration of cultural diversity into the global market? | A social network analysis methodology to analyze the cultural trade network and its temporal evolution among 66 countries in the Belt and Road region between 1990 and 2016 | The cultural trade network has promoted the integration of cultural diversity into the global market |

| Yeganeh [24] | The effects of cultural, religious, and linguistic differences on bilateral trade | Gravity model, using trade data for over 50 countries | Linguistic diversity hinders trade. But some differences in culture and religiosity can enhance international trade. |

| Mornah and MacDermott [9] | Which cultural aspects have a significant influence on bilateral trade performance or competitiveness? | Gravity model on trade data covering 59 countries and 29 years combined with the nine (GLOBE) culture dimensions, Population, GDP | Certain aspects of culture enhance bilateral trade performance/competitiveness. Performance Orientation, Future Orientation, Institutional Collectivism, Gender Egalitarianism, Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance improve bilateral trade performance while Assertiveness, Humane Orientation and In-Group Collectivism impair it. |

| Li, Han, Li, Wei, and Zhang [17] | The impact of cultural exchanges through Confucius Institutes on regional trade cooperation from three dimensions: improving cultural identity, reducing trade costs and sharing information | Gravity model and used trade data from the 64 countries along the line from 2004 to 2015 | The smaller the cultural distance, the stronger the promoting effects on the trade in BRI countries. |

| Xu et al. [21] | Examine the impact of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (CMSR) initiative and cultural distance on China’s forest product trade. | Used DID method based on quasi-natural experiments to evaluate the policy effects of the CMSR Initiative on forest product trade. Panel data on forest product trade between China and 78 countries from 1995 to 2017 | Cultural distance has a U-shaped relationship with China’s total forest product trade and exports. This means that as cultural distance increases, China’s forest product trade and exports show a trend of first decreasing and then increasing. |

| Year | Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Hatcheries | Seafood Processing | Sea Minerals | Ships, Port Equipment, and Parts Thereof | High-Technology and Other Manufactures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 3.467301 | 12.600405 | 0.006471 | 811.281141 | 153.652028 |

| 2013 | 2.990861 | 7.376872 | 0.059358 | 576.346918 | 163.693996 |

| 2014 | 3.080583 | 10.762019 | 0.017202 | 491.647604 | 241.932072 |

| 2015 | 2.392539 | 13.892134 | 0.020312 | 404.860056 | 223.800653 |

| 2016 | 4.055293 | 8.538384 | 0.021899 | 336.01063 | 154.762562 |

| 2017 | 5.984139 | 6.845285 | 0.024577 | 504.301851 | 155.511368 |

| 2018 | 7.273049 | 24.407227 | 0.034114 | 441.092557 | 139.604548 |

| 2019 | 8.028187 | 29.905686 | 0.087087 | 375.565235 | 198.171919 |

| 2020 | 2.625364 | 5.235185 | 0.035015 | 348.825931 | 308.776163 |

| 2021 | 2.49488 | 4.051819 | 0.029344 | 298.742034 | 324.811046 |

| Year | Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Hatcheries | Seafood Processing | Sea Minerals | Ships, Port Equipment and Parts Thereof | High-Technology and Other Manufactures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 0 | 0 | 0.287734 | 2.132082 | 45.629017 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0.0624 | 38.880435 | 30.264252 |

| 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.61933 | 54.411214 |

| 2015 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.09467 | 27.568955 |

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29.020062 | 39.545555 |

| 2017 | 0 | 0.053865 | 0 | 9.455668 | 49.540523 |

| 2018 | 0 | 0.034139 | 0 | 7.561958 | 59.65882 |

| 2019 | 0 | 0.041619 | 0 | 0.001373 | 75.726778 |

| 2020 | 0 | 0.019249 | 0 | 174.423879 | 65.905891 |

| 2021 | 0.20496 | 0.004821 | 0 | 151.220727 | 69.698455 |

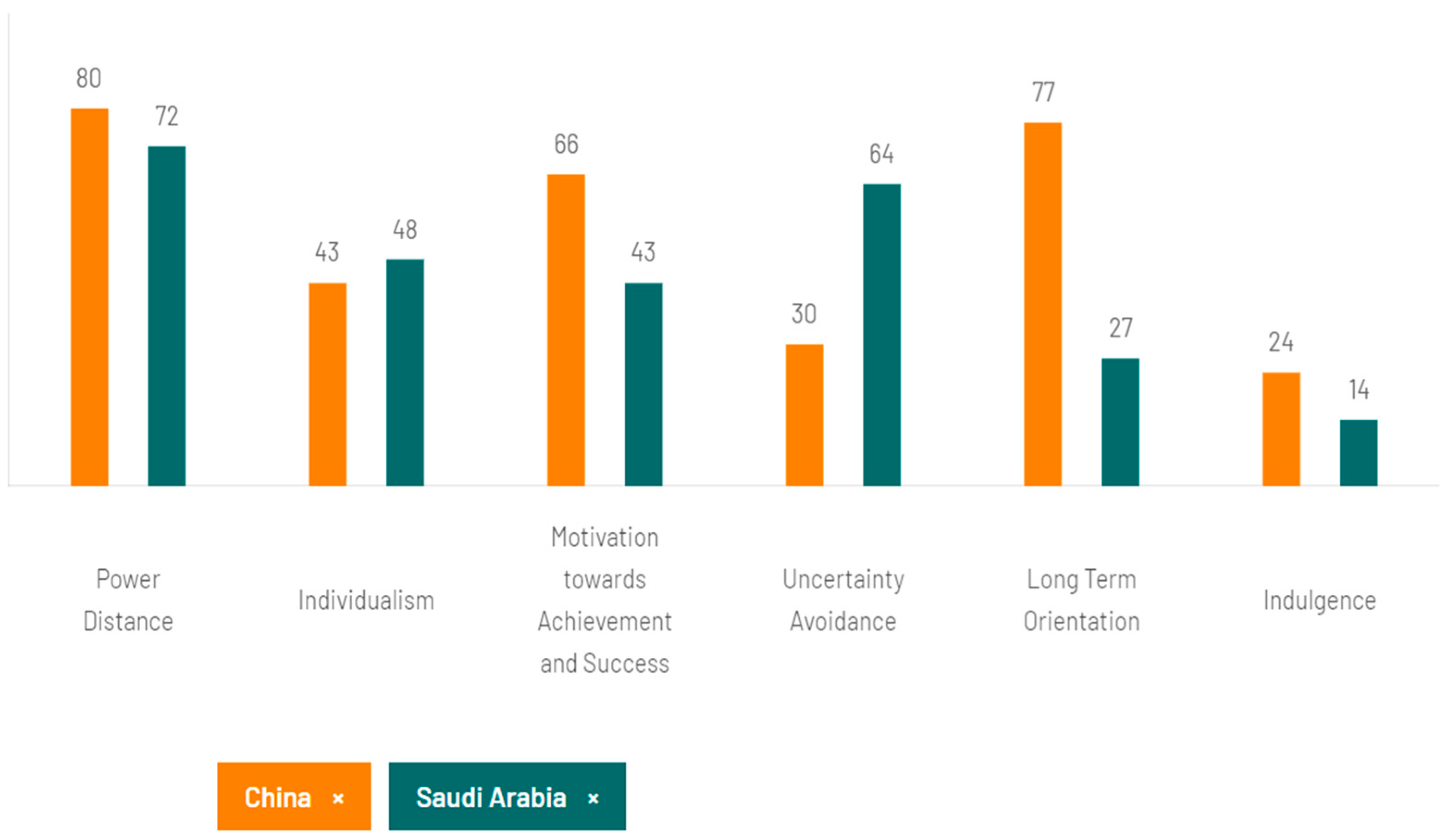

| Dimensions | Description | China | Saudi Arabia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Distance Index (PDI) | This dimension reflects the societal acceptance of inequality and the distribution of power. It describes how cultures perceive and tolerate disparities among their members, focusing on the degree to which individuals in less powerful positions within organizations and institutions recognize and endorse the uneven allocation of power. | With a Power Distance Index (PDI) of 80, China ranks high, indicating a societal acceptance of inequality. Relationships between subordinates and superiors are distinctly hierarchical, with little safeguard against the misuse of power by those above. Respect for formal authority and the belief in the potential for leadership and initiative are prevalent, while ambitions are expected to align with one’s social standing. | Saudi Arabia, with a PDI score of 72, shows a strong acceptance of structured hierarchies and centralized authority within organizations, reflecting societal acceptance of inherent inequalities. The culture endorses a clear hierarchical order that does not require justification, where subordinates anticipate directives and the ideal leader is viewed as a benevolent autocrat. |

| Individualism (IDV) | The Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV) dimension assesses whether a culture values personal independence and self-reliance or prioritizes group cohesion and interdependence. In individualistic societies, personal achievements and freedom are emphasized, while in collectivist cultures, the focus is on group goals, harmony, and mutual support. | China is characterized by a collectivist culture, indicated by a score of 43, emphasizing group over individual interests. This approach influences workplace dynamics, where decisions regarding hiring and promotions often favor those within a closer social circle, such as family. There is a generally low employee allegiance to colleagues, with a distinction between in-group cooperation and out-group detachment. Personal connections are prioritized above professional responsibilities and organizational objectives. | Saudi Arabia is mildly collectivist with a score of 48, emphasizing long-term commitment within groups such as family and extended relationships. Loyalty is highly valued, often superseding societal norms. The culture promotes strong, responsible relationships within groups, where personal offenses can lead to shame. In the workplace, relationships often mirror familial ties, with hiring and promotions favoring in-group members, and management focusing on group dynamics. |

| Motivation towards Achievement and Success | A society with a high score on this dimension prioritizes competition, achievement, and success, where being the best is the ultimate goal, beginning in education and persisting in the workplace. Conversely, a low score reflects a society valuing care for others and quality of life over individual achievements, where collective well-being and enjoying one’s work take precedence over competition. This distinction highlights the underlying motivations driving societal behavior: the pursuit of excellence versus the satisfaction in one’s endeavors. | With a score of 66, China places a strong emphasis on achievement and success. This cultural priority is evident in the willingness of individuals to forego personal time and family commitments for work opportunities, often working late hours and even relocating for better jobs. Education is also highly competitive, with students placing great importance on exams and rankings as measures of success. This drive for achievement permeates various aspects of Chinese society, prioritizing work and educational accomplishments over leisure. | With a score of 43, Saudi Arabia is identified as a society leaning more towards consensus, where there is a balanced emphasis on collective agreement and quality of life rather than on individual achievement and success. |

| Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI) | UAI measures a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. Societies with high UAI prefer clear rules and structures to manage unpredictability, seeking security in established norms. Conversely, cultures with low UAI are more adaptable, embracing change and uncertainty with ease, without the need for strict rules or predictable outcomes. | With a score of 30, China exhibits low Uncertainty Avoidance, indicating a society that is comfortable with ambiguity and pragmatic in its adherence to rules and laws. This flexibility in rulea-following allows for adaptability and entrepreneurship, characteristics seen in the prevalence of small-to-medium-sized, family-owned businesses. The Chinese language’s ambiguity reflects this comfort with uncertainty, challenging those from more literal cultures. This adaptability and entrepreneurial spirit are key to understanding China’s business landscape. | Saudi Arabia, with a score of 64 on Uncertainty Avoidance, shows a societal preference for structure and predictability. This indicates a culture with strict beliefs and behaviors, low tolerance for unconventional ideas, a significant need for rules, emphasis on hard work and punctuality, resistance to innovation, and a high value placed on security in motivating individuals. |

| Long-Term Orientation (LTO) | LTO assesses whether a society values long-term commitments and respect for tradition or prioritizes short-term gains and social norms. Cultures with a long-term orientation focus on future rewards, emphasizing perseverance, saving, and adaptability to changing circumstances. | With a score of 77, China is identified as a highly pragmatic culture, valuing adaptability, long-term planning, and resourcefulness. This pragmatism is reflected in a flexible approach to truth, based on context and time, and a focus on saving, investing, and perseverance towards long-term goals. | Saudi Arabia’s score of 27 in this dimension reflects its normative cultural orientation, emphasizing respect for traditions, a focus on absolute truths, and a preference for quick results over long-term savings. This indicates a society where traditional norms and immediate outcomes are prioritized. |

| Indulgence | This dimension measures the degree to which societies regulate or indulge in desires and impulses, influenced by upbringing. “Indulgence” signifies a society allowing relatively free gratification of basic human desires, while “Restraint” denotes societies where desires are strictly controlled. Cultures are thus categorized as either indulgent, showing leniency towards gratification, or restrained, emphasizing strict discipline and denial of gratification. | With a score of 24, China is classified as a Restrained society, indicating a tendency towards cynicism and pessimism. Unlike indulgent cultures, restrained societies place less value on leisure and more on controlling desires. Individuals in these societies often feel their behaviors are limited by social norms and view self-indulgence with skepticism. | Saudi Arabia, scoring 14 on this dimension, is markedly a Restrained society. This score reflects a cultural orientation that prioritizes strict control over desires and leisure, emphasizing the importance of adhering to social norms. Individuals in such societies often believe that self-indulgence is inappropriate, guided by a strong sense of restraint shaped by societal expectations. |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All creative goods | 1717 | 1826 | 1820 | 2246 | 1851 | 1925 | 1838 | 2777 | 3277 | 3378 |

| Design | 1375 | 1443 | 1516 | 1919 | 1559 | 1675 | 1581 | 2420 | 2889 | 2940 |

| Interior | 748 | 793 | 831 | 1111 | 841 | 826 | 747 | 1124 | 1498 | 1558 |

| Toys | 93 | 82 | 98 | 140 | 164 | 287 | 335 | 570 | 939 | 775 |

| Fashion | 481 | 502 | 525 | 611 | 517 | 508 | 464 | 676 | 410 | 491 |

| Art crafts | 120 | 120 | 129 | 168 | 125 | 142 | 131 | 162 | 191 | 186 |

| Visual arts | 149 | 198 | 128 | 116 | 127 | 79 | 76 | 123 | 122 | 132 |

| Sculpture | 146 | 194 | 125 | 111 | 123 | 77 | 74 | 120 | 118 | 125 |

| jewelry | 9 | 25 | 48 | 49 | 31 | 48 | 31 | 46 | 38 | 108 |

| New media | 45 | 47 | 31 | 27 | 26 | 15 | 39 | 56 | 55 | 104 |

| Video games | 19 | 19 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 29 | 43 | 44 | 93 |

| ICT Items | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1769 | 1662 | 1572 | 1480 | 1565 | 1879 | 2222 | 2688 | 2635 | 3114 |

| % World | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.36 |

| Computers and peripheral equipment | 343 | 303 | 286 | 183 | 181 | 220 | 227 | 300 | 299 | 384 |

| Communication equipment | 946 | 846 | 775 | 724 | 912 | 1154 | 1453 | 1666 | 1584 | 1968 |

| Consumer electronic equipment | 438 | 464 | 469 | 524 | 420 | 470 | 493 | 575 | 683 | 692 |

| Electronic components | 15 | 24 | 16 | 23 | 23 | 14 | 33 | 122 | 34 | 35 |

| Miscellaneous | 27 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 29 | 21 | 16 | 26 | 35 | 36 |

| Variables | Description | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Maritime Trade (MT) | The transport of goods overseas between two countries as the dependent variable. | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) |

| Creative Goods Export (CRE) | Creation, production, and distribution cycles that leverage creativity and intellectual capital, which is the main regressor. | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) |

| Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Goods | Computer and communications services (telecommunications and postal and courier services) and information services (computer data and news-related service transactions), which is the second regressor. | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) |

| Population (POP) | The whole number of people in a country, which is the third regressor. | World Bank |

| Variables | Level | First Difference | Second Difference | Order of Integration I(d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT | Adj t-Stat critical Prob. | −3.435659 | - | - | I (0) |

| −2.945842 | - | - | |||

| (0.0161) | - | - | |||

| CRE | Adj t-Stat critical Prob. | 0.013089 | −1.780727 | −2.689788 | I (2) |

| −2.945842 | −1.950687 | −1.951000 | |||

| (0.9537) | (0.0714) | (0.0087) | |||

| ICT | Adj t-Stat critical Prob. | 1.313362 | −0.708336 | −2.249313 | I (2) |

| −2.945842 | −1.950687 | −1.951000 | |||

| (0.9982) | (0.4027) | (0.0256) | |||

| POP | Adj t-Stat critical Prob. | −2.639918 | −1.872908 | −2.115859 | I (2) |

| −2.945842 | −1.950687 | −1.951000 | |||

| (0.0946) | (0.0631) | (0.0348) |

| Lag | Log L | LR | FPE | AIC | SC | HQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −1521.982 | NA | 6.71 × 1037 | 98.45045 | 98.63548 | 98.51077 |

| 1 | −1232.995 | 484.7520 | 1.52 × 1030 | 80.83840 | 81.76356 | 81.13998 |

| 2 | −1059.953 | 245.6077 | 6.42 × 1025 | 70.10668 | 72.37195 | 71.249520 |

| 3 | −921.173 | 161.1649 | 2.71 × 1022 | 62.78533 | 65.19073 | 63.56943 |

| 4 | −883.799 | 33.7571 | 9.41 × 1021 | 61.40637 | 64.55189 | 62.43173 |

| 5 | −682.713 | 129.7328 | 1.16 × 1017 | 49.46535 | 53.35099 | 50.73197 |

| 6 | −419.740 | 101.7959 * | 5.14 × 1010 * | 33.53161 * | 38.15738 * | 35.03950 * |

| MT | CRE | ICT | POP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lag 1 | 1400.438 | 321.4806 | 515.8616 | 855.9552 |

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | |

| Lag 2 | 455.0856 | 947.3936 | 144.9993 | 252.3924 |

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] |

| Cause | Wald Statistic Chi-Squared | Probability-Value (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| CRE → MT | 132.8747 | 0.0000 |

| ICT → MT | 97.47595 | 0.0000 |

| POP → MT | 73.80341 | 0.0000 |

| MT → CRE | 8.038658 | 0.0180 |

| ICT → CRE | 4.642749 | 0.0981 |

| POP → CRE | 19.95078 | 0.0000 |

| MT → ICT | 12.39070 | 0.0020 |

| CRE → ICT | 4.386837 | 0.1115 |

| POP → ICT | 3.105710 | 0.2116 |

| MT → POP | 5.049702 | 0.0801 |

| CRE → POP | 1.494005 | 0.4738 |

| ICT → POP | 0.732785 | 0.6932 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamed, N.M.A.; Binsuwadan, J.; Abdelkhalek, R.H.M.; Frega, K.A.-E.A. The Analysis of Cultural Convergence and Maritime Trade Between China and Saudi Arabia: Toda–Yamamoto Granger Causality. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146501

Mohamed NMA, Binsuwadan J, Abdelkhalek RHM, Frega KA-EA. The Analysis of Cultural Convergence and Maritime Trade Between China and Saudi Arabia: Toda–Yamamoto Granger Causality. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146501

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed, Nashwa Mostafa Ali, Jawaher Binsuwadan, Rania Hassan Mohammed Abdelkhalek, and Kamilia Abd-Elhaleem Ahmed Frega. 2025. "The Analysis of Cultural Convergence and Maritime Trade Between China and Saudi Arabia: Toda–Yamamoto Granger Causality" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146501

APA StyleMohamed, N. M. A., Binsuwadan, J., Abdelkhalek, R. H. M., & Frega, K. A.-E. A. (2025). The Analysis of Cultural Convergence and Maritime Trade Between China and Saudi Arabia: Toda–Yamamoto Granger Causality. Sustainability, 17(14), 6501. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146501