1. Introduction

Urbanization, as a key driver of socio-economic development [

1], has reshaped landscapes and influenced public health. With the growing urban population, individuals’ needs have shifted from basic physiological requirements to physical and mental well-being. This has led to the development of urban green spaces and parks, which aim to restore mental and emotional energy [

2,

3,

4]. However, the health implications of these landscape transformations, particularly in the context of tourism, remain underexplored.

In China, short-distance city tours and local leisure tourism have emerged as key drivers of economic internal circulation [

5], while urban tourism landscapes, enriched by natural and humanistic settings, not only reshape cultural perceptions but also alleviate modern life pressures [

6,

7]. Tourism activities, offering experiences beyond daily routines, are increasingly shaped by tourists’ needs for physical and mental well-being [

8]. While these landscapes promote emotional expression and stress relief, the mechanisms through which they enhance health remain poorly understood, particularly in the context of varying urbanization levels [

9,

10].

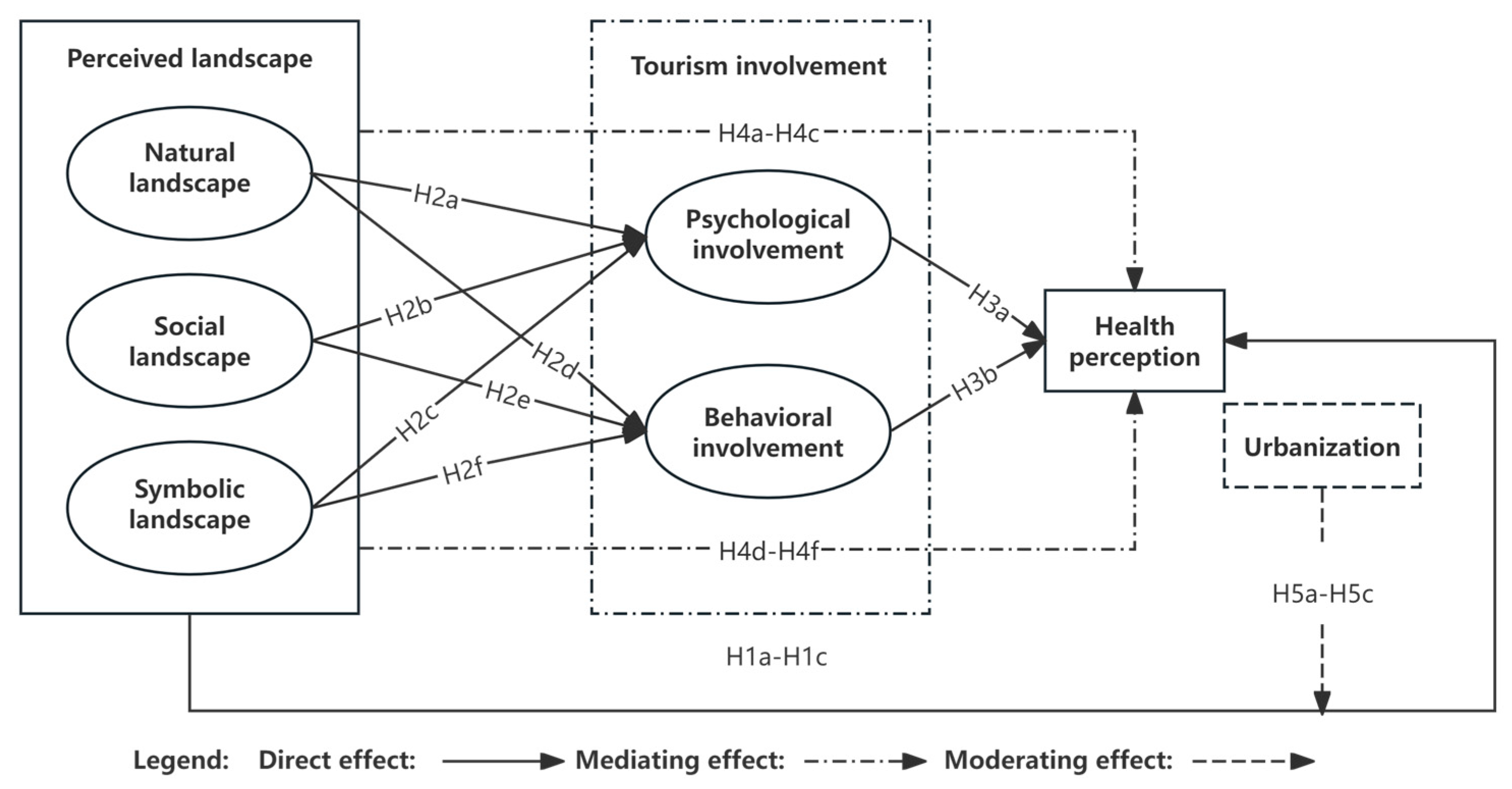

This study aims to explore how tourism landscapes promote physical and mental health in the context of urbanization. Specifically, it constructs a model based on therapeutic landscape theory and tourism involvement theory to examine the impact of natural, social, and symbolic landscapes on tourists’ health perceptions. Additionally, it investigates the mediating role of tourism involvement and the moderating effect of urbanization levels on these relationships. By doing so, the study seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of the health-promoting mechanisms of tourism landscapes under varying urbanization conditions.

With the rapid development of tourism, the socio-cultural structure of tourist destinations is undergoing profound changes, with the “localization of tourists” becoming an important phenomena, which reflects the gradual integration of tourists into local societies through long-term stays or frequent visits [

11]. Building upon this phenomenon, contemporary tourism demonstrates enhanced tourist–place interactions, wherein the travel process itself constitutes both adaptation to local contexts and innovation of cultural practices [

12]. Consequently, tourists’ destination perceptions—including landscape appraisal and cultural interpretation—have intensified to unprecedented levels, thereby justifying our primary reliance on tourist-sourced data collection.

In this study, the subjective health perception of tourists is used as an observational variable to investigate the health-promoting effects of tourist landscapes. The study analyzes how tourism landscapes act on tourists to produce health effects and explores the role of urbanization in health-promotion mechanisms. Theoretically, this study examines how therapeutic landscapes enhance tourists’ physical and mental health, explores the mutual development model of urbanization and tourist well-being, and contributes to providing a theoretical basis for modeling the health effects of urbanization, enriching therapeutic landscape theory and tourism involvement theory. This study integrates theories from health geography and tourist behavior studies, facilitating cross-disciplinary research innovation and providing a reference model for interdisciplinary studies in tourism research. Practically, the findings provide a scientific basis for the sustainable development of tourist destinations, emphasizing the enhancement of tourists’ health and well-being through landscape design and urban planning.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Therapeutic Landscape and Tourists’ Health Perception

The concept of therapeutic landscapes, introduced by health geographer Gesler (1992), refers to settings renowned for fostering physical, psychological, and spiritual healing, encompassing natural, social, and symbolic environments [

13] (

Table 1). Early research prior to 2004 predominantly conceptualized healing as an inherent landscape characteristic [

14]. A shift occurred when Conradson (2005), in his study of therapeutic encounters in rural England, progressively realized that healing landscapes have relational attributes as a way to heal through complex interactions between individuals and their wider social–physical environments. Subsequent research expanded this perspective through frameworks like “Healing Set” (Foley, 2011) [

15], “Empowering Place” (Duff, 2011) [

16], and “Healing Mobility” (Gatrell, 2013) [

17], highlighting the dynamic interplay of natural, social, and symbolic dimensions [

13,

18].

Therapeutic landscapes, as a framework guiding “health tourism,” “wellness tourism,” and “ecotourism,” offer a fresh perspective for understanding the significance of tourism. A systematic review of recent studies reveals that Huang et al. (2022), employing therapeutic landscape theory across spatial, temporal, and social dimensions, found that the therapeutic meaning of daily life in tourism emerges from dynamic interactions among the environment, routines, tourists, and destinations [

19]. Craik’s study (2023) found that health benefits emerge from the dynamic interplay of multiple therapeutic spaces, where individual facilities are reconfigured through their interactions, flows and temporal connections [

20]. He Qing (2023) further explored how therapeutic landscapes facilitate engaged and meaningful well-being, comprehensively examining the place–health relationship [

21]. Wang et al. (2024) identified tourists’ physical health as an outcome of the combined effects of sensory experiences and other factors [

22].

However, existing studies often homogenize therapeutic landscapes as a whole, with limited systematic analysis of their natural, social, and symbolic dimensions. The characteristic distinctions among these landscape types remain understudied. Current research predominantly employs qualitative methods like interviews and content analysis, while quantitative approaches are scarce. Moreover, as therapeutic landscape theory originated in the West, studies in Eastern contexts—particularly China, with its rich cultural traditions and distinct landscape configurations—are still nascent. This study therefore focuses on examining the unique characteristics and health-promoting mechanisms of therapeutic landscapes in the Chinese context.

Table 1.

Three dimensions of therapeutic landscape.

Table 1.

Three dimensions of therapeutic landscape.

| Dimension | Key Characteristics |

|---|

Natural

Landscapes | - -

Interaction with natural/built environments induces therapeutic effects [ 23]. - -

Natural activities: green space wandering, forest hiking [ 24], park relaxation [ 25]. - -

The built environment includes wellness resorts and spa facilities [ 26]. - -

Nature immersion promotes overall health. - -

The built environment also facilitates healing experiences.

|

Social

Landscapes | - -

Emerge through human interactions in therapeutic settings [ 27]. - -

Tourist motivations: seasonal comfort [ 27], wellness [ 28], rehabilitation [ 29]. - -

Shared activities (gardening, Tai Chi, dancing) enhance social connections.

|

Symbolic

Landscapes | - -

Derived from place-based symbolic meanings [ 27]. - -

Health effects through cultural interpretations (longevity culture, TCM, yin–yang philosophy) [ 30, 31]. - -

Encompasses rituals, values, meaning creation and symbolic objects (e.g., wind–rain bridges) [ 32]. - -

The symbolic environment shapes tourists’ experiences and well-being.

|

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: Natural landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on tourists’ health perceptions.

H1b: Social landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on tourists’ health perceptions.

H1c: Symbolic landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on tourists’ health perceptions.

2.2. Therapeutic Landscape and Tourism Involvement

Involvement theory, rooted in psychological self-involvement and social judgment theory [

33], refers to the degree of personal relevance an individual assigns to an object, activity, or experience based on their needs, values, and interests [

34]. In consumption research, “consumption involvement” emerged in the mid-1960s [

35], while “leisure involvement” gained attention in the late 1980s [

36]. Although involvement is closely linked to psychological states, its manifestation is often assessed through observable behaviors, leading to its classification into behavioral involvement (observable actions) and psychological involvement (subjective engagement) [

37]. Within the context of therapeutic landscapes, this study examines tourism involvement through two dimensions:

Tourism behavioral involvement—the intensity of time and effort tourists invest in engaging with therapeutic landscapes.

Tourism psychological involvement—tourists’ emotional and cognitive identification with therapeutic landscapes.

Existing research primarily explores tourism psychological involvement in relation to destination image, satisfaction, revisit intention, tourist behavior, and motivation. However, studies on tourism behavioral involvement remain scarce. Furthermore, while tourism involvement has been examined in rural, sports, and virtual tourism contexts, health tourism—particularly therapeutic landscapes—has received limited attention.

Therapeutic landscapes provide multisensory experiences [

38], including visual, auditory, and tactile stimuli, which encourage active participation. For instance, natural landscapes rich in negative oxygen ions may prompt health-enhancing activities such as walking, tai chi, or meditation. Tourists often emulate others’ behaviors to assimilate into the destination, reinforcing their engagement. Additionally, symbolic landscapes are interpreted through cultural lenses [

39], fostering connections with intangible elements and tangible elements. For instance, they explore longevity culture by meeting centenarians and experience “yin and yang balance” through the sensations of sand therapy.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: Natural landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on psychological involvement in tourism.

H2b: Social landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on psychological involvement in tourism.

H2c: Symbolic landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on psychological involvement in tourism.

H2d: Natural landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on behavioral involvement in tourism.

H2e: Social landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on behavioral involvement in tourism.

H2f: Symbolic landscape perception has a significantly positive influence on behavioral involvement in tourism.

2.3. Tourism Involvement and Health Perception

Current research on therapeutic landscapes predominantly examines the mechanism of action of local rehabilitation, ignoring the potential influence of internal factors. However, internal factors also have an impact on tourists’ health perceptions, such as personality optimism [

27]. Most studies have tended to disregard the exploration of behavioral endogenous factors. Consequently, there is a pressing need for further research on the relationship between internal factors and health perception, with a particular emphasis on the integrated perspective of psychological and behavioral internal factors.

The higher the psychological involvement of tourists the easier it is for them to engage in tourism activities, facilitate deeper interactions with the destination, actively participate in the experience, and better realize their health recovery needs [

40,

41]. Landscapes with high therapeutic potential (e.g., rivers, mountains) stimulate sensory engagement, promoting mental alertness and relaxation [

42].

Deep involvement in tourism heightens interest and place identity. With greater behavioral involvement, tourists’ connection to the destination strengthens, and their understanding of the destination’s rehabilitation attributes, such as its natural, social, and symbolic landscapes, deepens. Highly involved tourists invest more in planning and participating in tourism, perceiving the health effects of the environment more keenly [

43].

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: Tourism psychological involvement has a significant positive effect on tourists’ health perception.

H3b: Tourism behavioral involvement has a significant positive effect on tourists’ health perception.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Tourism Involvement

Recent tourism research has begun exploring tourism involvement as a mediator between tourism perceptions and tourism experience outcomes. While some studies have examined its mediating role between therapeutic landscape perceptions and health perceptions, this remains an underdeveloped area of inquiry, particularly regarding the combined psychological and behavioral dimensions of involvement.

Zhang (2021) argue that “therapeutic experiences” are a crucial resource for the exchange and interaction between tourists and destinations, and can elucidate the process of health promotion [

27]. However, these experiences are predominantly described in psychological terms, with little consideration of the crucial role of behaviors. When tourists perceive therapeutic landscapes (natural, social, and symbolic), they develop both psychological identification with these landscapes’ therapeutic properties and willingness to invest resources in related activities. This dual process of psychological and behavioral involvement subsequently influences health perceptions through varying degrees of engagement.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a: Tourism psychological involvement mediates the relationship between perceived natural landscape and perceived health.

H4b: Tourism psychological involvement mediates the relationship between perceived social landscape and perceived health.

H4c: Tourism psychological involvement mediates between perceived symbolic landscapes and health perceptions.

H4d: Tourism behavioral involvement mediates between perceived natural landscapes and perceived health.

H4e: Tourism behavioral involvement mediates between perceived social landscape and perceived health.

H4f: Tourism behavioral involvement mediates the relationship between perceived symbolic landscapes and perceived health.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Urbanization

Urbanization is a multifaceted process intertwined with socioeconomic development, shifts in land use, transformations in the built environment, and evolving lifestyles [

41]. These changes profoundly reshape human interactions with local landscapes [

44,

45], with significant implications for health and well-being [

45]. Although the nexus between urbanization and health has been widely examined, scholarly perspectives remain divided [

46]. On one hand, urbanization is often critiqued for its adverse effects, including environmental degradation, resource overconsumption, and widening urban–rural disparities. On the other hand, cities concentrate social resources—such as healthcare, education, and employment—that can elevate health awareness and outcomes. This is evident in tourism contexts, where urban infrastructure enhances visitor experiences [

47].

However, existing studies predominantly adopt macro- or meso-level analyses, relying on official annual data, while neglecting the micro-level influence of perceived urbanization on individual health. This gap is particularly salient in tourism research, where subjective perceptions shape the meaning and value ascribed to landscapes [

48]. As tourism is temporary and heterogeneous, tourists are unable to longitudinally assess urbanization’s progression and are limited to the impact of urbanization at a certain point in time. Their health perceptions are inevitably shaped by immediate, personal encounters with urbanized spaces. Therefore, there is a need to explore the impact of urbanization on personal health from the perspective of tourists’ perceptions.

Urbanization can negatively impact natural landscapes but also reshapes urban spaces and enhances management for better natural landscapes in tourist areas, benefiting tourists’ health. First, it speeds up development of artificial landscapes like green spaces and parks. Second, anthropogenic and orderly ecological restoration and reconstruction can effectively improve the state of urban natural landscapes [

49,

50]. Third, urbanization is conducive to improving residents’ quality and health awareness, enhancing the maintenance of local landscapes, and promoting sustainable development of natural landscapes, providing stable and lasting health benefits.

Notably, destinations renowned for therapeutic attributes—such as Sanya’s winter retreats for elderly migrants [

27] or Bama’s recuperative enclaves for ailing visitors [

29]—cultivate supportive social ecosystems that amplify health perceptions. Urbanization facilitates this by fostering niche communities [

51,

52]. Shared identities and mutual support among tourists—whether through neighborly camaraderie, illness-based solidarity, or collective place attachment—co-construct healing experiences [

30,

53].

Symbolic landscapes, though vulnerable to rapid urbanization, also undergo reinvention. Urbanization reconfigures their meanings, aligning them with contemporary health narratives. For example, Dong wind and rain bridges, good fortune and the avoidance of bad luck [

32], centenarians, who symbolize the culture of longevity [

19], and Xinjiang sand therapy, which promotes the “balance of yin and yang” [

31], reflect dynamic reinterpretations of tradition. Urbanization reinforces the connection between symbolic landscapes and tourists’ health perceptions, prompting cultural reinterpretations that enrich their meaning [

39]. Furthermore, urbanization enhances symbolic communication, enabling diverse audiences to decode health-related metaphors embedded in landscapes.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a: Urbanization positively moderates the relationship between perceived natural landscape and tourists’ perceived health.

H5b: Urbanization positively moderates the relationship between perceived social landscapes and tourists’ health perceptions.

H5c: Urbanization positively moderates the relationship between perceived symbolic landscapes and tourists’ health perceptions.

Overall, we conducted five sub-studies to test our research model (

Figure 1) and hypotheses. In exploring the mechanism of how the perceived therapeutic landscape (natural, social, symbolic) influences tourists’ health perception, this study introduces tourism involvement (tourism psychological involvement and behavioral involvement) to test its potential mediating role. Based on existing theoretical and empirical studies, we propose the following hypotheses in order: Firstly, we propose the direct effect of perceived therapeutic landscape on tourists’ health perception (H1a–H1c). Secondly, we propose the effect of perceived therapeutic landscape on tourism involvement (H2a–H2f) to explore the antecedent path of the mediating variable. We also propose the effect of tourism involvement on health perception (H3a–H3b) to explore the consequent path of the mediating variable. Finally, the hypothesis of the mediating role of tourism involvement (H4a–H4f) is proposed to form a complete logical chain of hypotheses, aiming to explore two possible paths of realization of the perceived therapeutic landscape affecting tourists’ health perception: the direct influence path and the mediating influence path through tourism involvement. Additionally, the hypothesis of the moderating effect of urbanization on the relationship between perceived therapeutic landscape and tourists’ health perception has been proposed (H5a–H5c).

3. Research Methodology

Adopting a quantitative research approach, this study examines the effects of therapeutic landscapes on tourists’ physical and psychological well-being within urbanization contexts. Data were collected via a structured questionnaire comprising six sections. The first five sections employed a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), while the sixth gathered demographic details: ① Therapeutic Landscape Perception Scale—Adapted from Gesler’s (1992) framework [

13] and refined by Huang and Xu (2018) [

28], this 13-item scale evaluates tourists’ perceptions of natural, social, and symbolic landscapes (

Table A1). ② Tourism Involvement Scale—Assessed through psychological (adapted from Zaichkowsky’s RPII, 1994) [

34] and behavioral engagement (time, expenditure, and effort invested), this scale includes 7 items (

Table A2). ③ Tourist Health Perception Scale—Based on Anthony Capon’s (2017) General Health Scale and Universal Health Needs [

54], this 9-item measure accounts for both biophysical and psychosocial health dimensions. Tourist health perception is measured through 9 specific indicators in different dimensions such as physical condition, physical fitness, psychological state, and relationship management (

Table A3). ④ Urbanization Perception Scale—Modified from Li et al. (2023) [

32], this 11-item scale captures subjective evaluations of urbanization across domains such as population growth, economic development, employment, infrastructure, spatial expansion, and green space availability (

Table A4). ⑤ Recreational and Health Activity Preferences—This explores visitors’ motivations, frequency of visits, duration of stay, preferred leisure facilities, and information sources regarding Lintong’s tourist offerings. ⑥ Demographic Information—This includes gender, age, education, occupation, monthly income, and place of origin.

3.1. Research Area

This study adopts Wu’s (2001) Recreational Belt Around Metropolis (ReBAM) model [

55] to analyze Xi’an’s urban recreation zones, which are categorized into three spatial tiers: ① near-city recreation zone (5–20 km from the Bell Tower, ≤0.5 h by public transport), covering Xi’an’s urban core; ② peri-urban recreation zone (20–50 km, 0.5–1.5 h), serving as a transitional leisure space; ③ far-suburban zone (50–100 km, 1.5–2.5 h), extending into the broader Guanzhong region. With a resident population of 13.07 million, Xi’an exhibits robust demand for suburban tourism. This study takes Lintong District, a suburban recreation area in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, as the study area (

Figure 2).

The development of tourism in Lintong can be divided into two stages. The first is the sightseeing tourism stage (1979–2013), initiated by the 1979 Terracotta Warriors exhibition, during which tourism became a regional economic pillar. The second is the health and wellness tourism stage, (2013–2025), including experiential tourism marked by Tang Culture and vacation tourism represented by hot springs. Infrastructure such as Angsana Xi’an Lintong, Lintong Sanatorium, and Hongde Recreation Base has solidified Lintong’s identity as a wellness destination. The Industrial Development and Layout Plan of Lintong District (2025–2035) further integrates culture, tourism, and healthcare, positioning Lintong as a national-level recreation hub. This area’s spatial representativeness and developmental trajectory align closely with the study’s objectives, offering critical insights into urbanization’s interplay with leisure and health tourism.

3.2. Data Collection

This research purposely chose the tourists visiting Lintong as the survey object, using both online and offline approaches to collect data, and offline came to collect data near Lintong’s tourist spots and hot spring hotels, which was done in order to be able to make sure that the tourists had experienced the therapeutic landscape of the tourist destination. Before the formal research, a pre-survey was conducted online in January 2024, and 30 valid questionnaires were collected. Adjustments were made to the questionnaire based on feedback, simplifying challenging questions for scientific and standardized research. The main research ran from May 14th to 25th, 2024, using Questionnaire Star online and random sampling offline.

The prevailing methodological standards suggest calculating the minimum required sample size by multiplying the total questionnaire items by a factor of 5. Our survey instrument comprised 46 measurement items, yielding 342 responses. After removing the invalid responses (incomplete answers, wrong answers, no change in answers), 304 valid responses were left, with a valid response rate of 88.9%, which satisfactorily meets and surpasses this established criterion (46 items × 5 = 230, minimum threshold).

Table 2 shows that 46.1% were males, while 53.9% were females; 62.8% were between 21 and 40 years old; and 66.1 % were well-educated, with Bachelor’s degrees or higher. The public prefers hot spring hotels, accounting for 53.5%, followed by sanatoriums, accounting for 16.5%, regarding their preferences for recreational and healthcare institutions. Most people visited Lintong for the first time, 44.7%, while 34.9% visited three times or more; 41.9% stayed in Lintong for two days or more, followed by one day, 26.7%. Of the respondents, 43.2% traveled with family or relatives, while 30% traveled with friends.

3.3. Measurement Model

Currently, there are two widely used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approaches: Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) and Partial Least Squares-based Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The former is based on covariance, while the latter is based on variance (partial least squares). In this study, PLS-SEM was used to analyze the data for the following main reasons:

(1) CB-SEM and PLS-SEM are equally effective for developing and analyzing structural relationships, though CB-SEM has more stringent data requirements, while PLS-SEM is more lenient [

56]. PLS-SEM can effectively analyze partial questionnaire items and is well-suited for small sample sizes and non-normal distributions [

57]. The PLS-SEM approach demonstrates superior construct reliability and validity, as evidenced by its higher average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) values compared to CB-SEM [

56]. This approach aligns well with the data collected in this study.

(2) The methodological choice between CB-SEM and PLS-SEM hinges on distinct research goals: CB-SEM serves as the optimal approach for confirmatory theory testing, while PLS-SEM proves more effective for exploratory prediction and theoretical advancement [

56]. PLS-SEM is suitable for exploratory theoretical research, as it aids in uncovering novel causal relationships and predicting complex variable interactions within a model [

58]. Given the study’s exploratory goals to examine the mediating role of tourism involvement and the moderating effect of perceived urbanization level, along with the testing of five sets of hypotheses, PLS-SEM provides an appropriate analytical framework for investigating these complex intricate relationships.

3.4. Common Method Variance

Common Method Variance (CMV) refers to the artificial covariance between the independent and dependent variables due to the same data source, measurement environment, and the characteristics of the measurement items. In this study, the Harman one-way test was used. According to the criterion that the variance of the eigenvalues of a single factor should not exceed 50% [

59], exploratory factor analysis was conducted using SPSS 27, which resulted in an explanatory rate of the first principal component factor of 17.131%, which was by the criteria for determining the criterion, thus indicating that the data in this study did not have standard severe method variance.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study is based on therapeutic landscape theory and tourism involvement theory, integrating methodologies from health geography, tourist behavior studies, sociology, management, and other interdisciplinary fields. It focuses on tourists in Lintong District to explore the relationship between therapeutic landscapes and individual health benefits. By introducing tourism involvement as a mediating variable and urbanization as a moderating variable, the study delves into how therapeutic landscapes in tourist destinations promote individual health against the backdrop of urbanization. The specific discussions and conclusions are as follows:

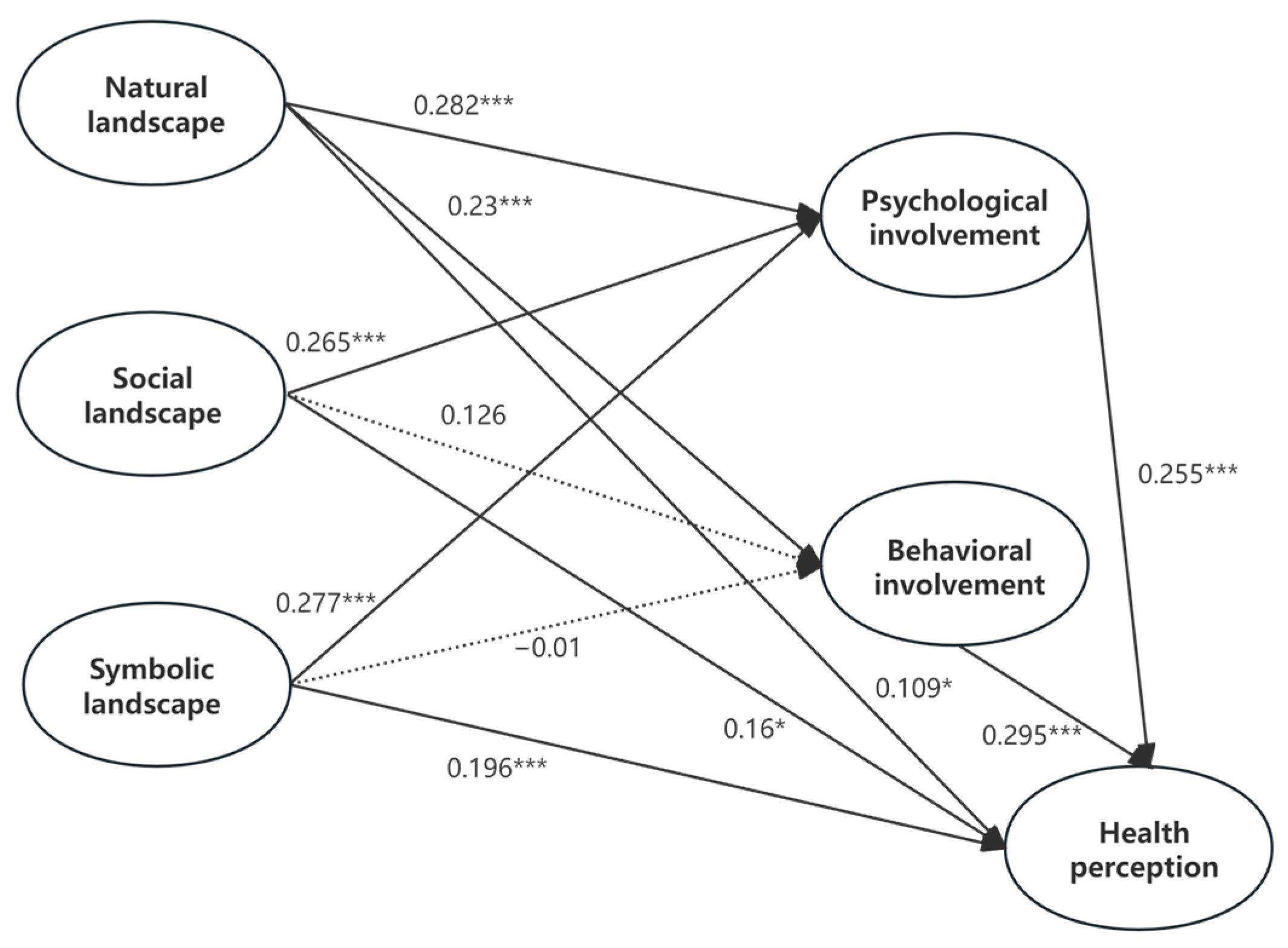

(1) This study constructs a model of the impact of therapeutic landscapes on individual health in the context of urbanization. The influence of therapeutic landscapes on individual health is the result of three dimensions working together. Specifically, the optimization of natural landscapes, the development of social landscapes, and the deepening of symbolic landscapes all have significant positive effects on individual health perception, which aligns with the findings of Zhang et al. [

27]. Natural landscapes have the most pronounced impact on individual health benefits because elements such as good air quality, clear water bodies, and rich flora and fauna serve as foundational conditions for promoting health. Immersion in natural landscapes allows individuals to experience relaxation, comfort, and joy, thereby enhancing their well-being. Social landscapes provide a safe and comfortable living environment, enabling individuals to reconstruct social relationships through interactions with destinations, residents, and other tourists, thereby alleviating stress from daily life. In an inclusive, friendly, and welcoming social atmosphere, individuals compensate for the lack of social connections in their everyday lives. Symbolic landscapes emphasize the deep connection between people and places. When individuals immerse themselves in local tourism activities and landscapes, they are more likely to generate positive associations and gain beneficial health experiences [

30]. The impact of therapeutic landscapes on individual health is essentially a dynamic and interactive process between people and places, where individuals establish emotional connections and perceive health benefits through deep engagement with the landscapes.

(2) Tourism involvement positively moderates the relationship between natural landscapes, social landscapes, symbolic landscapes, and individual health. Psychological involvement in tourism plays a fully mediating role, while behavioral involvement plays a partially mediating role. This finding supports the research of Huang Jie et al. [

41], further emphasizing the role of tourism involvement in individual health perception. A high level of involvement activates individuals’ desire to explore landscapes, prolongs their stay in these spaces, and strengthens their interaction with the landscapes. Additionally, highly involved individuals are more likely to overcome the barriers of being strangers. They are more willing to spend time and energy immersing themselves in the local social atmosphere, forming strong connections through deep social interactions. By enhancing place identity and self-efficacy [

36], they alleviate social alienation and improve individual health perception. Finally, regarding the relationship between the third type of therapeutic landscape (symbolic landscapes) and individual health, tourism involvement—particularly psychological involvement—demonstrates the most significant mediating effect. This finding corroborates Chen et al.’s research, which posits that tourists interpret and evaluate destination-based symbolic landscapes through the lens of their own cultural values [

39]. Such interpretation encompasses both intangible cultural connotations and tangible physical representations. Furthermore, by differentiating and analyzing the distinct mediating roles of psychological versus behavioral involvement in tourism, this study provides a more nuanced extension of prior research. Symbolic landscapes, which involve meaning-making and atmosphere-creation, enable highly engaged tourists to connect isolated symbolic nodes (e.g., individual landmarks) to broader cultural representations of leisure and slow living. Deep engagement encourages them to internalize external aesthetic elements as personal value perceptions, thereby enhancing psychological well-being. The meaning tourists ascribe to symbolic landscapes fosters emotional resonance, bridging intangible health-related significance with tangible destination features. This process elevates individual mental health, explaining why psychological involvement plays a more pronounced mediating role in the context of symbolic landscapes.

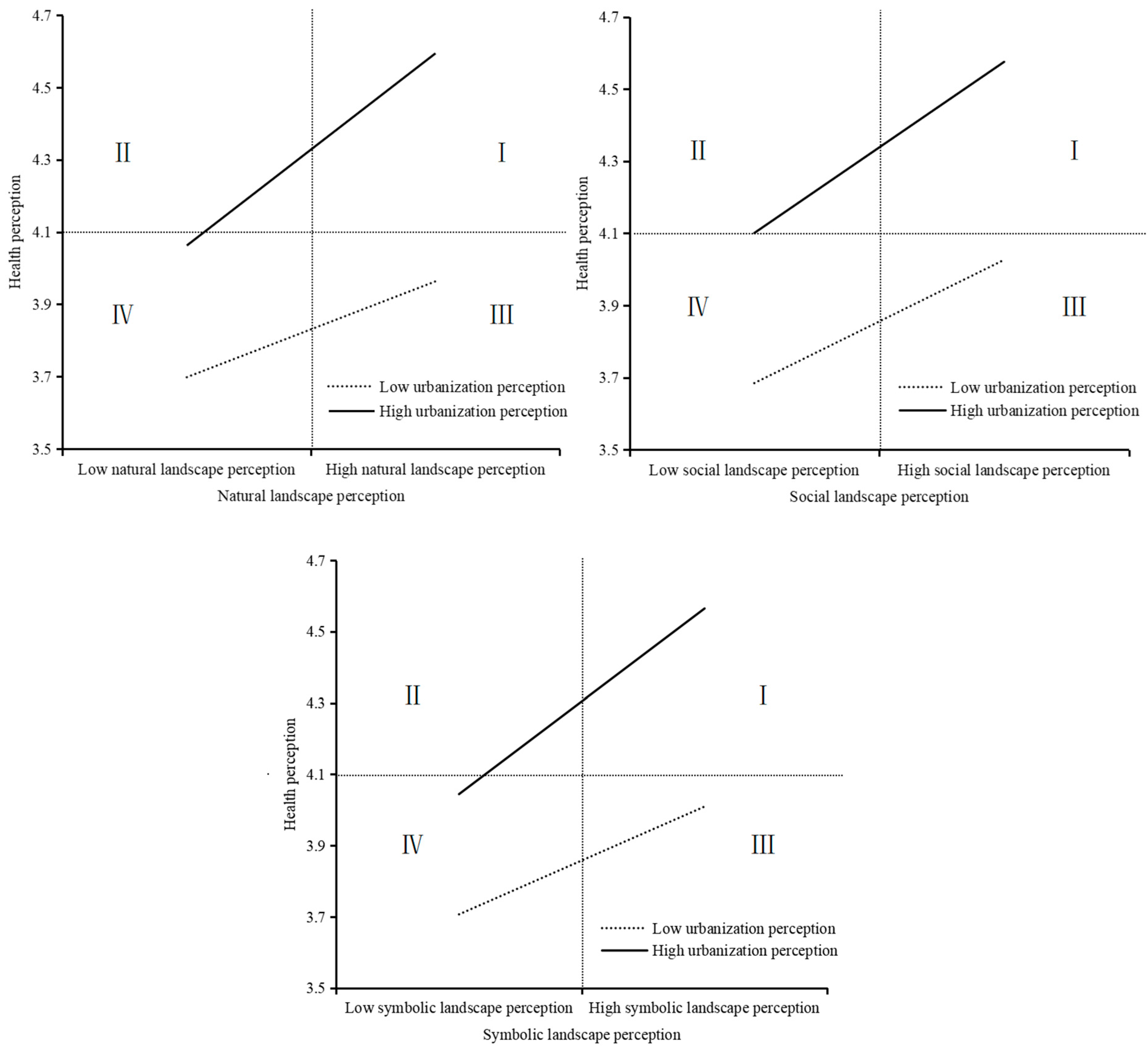

(3) Urbanization moderates the relationship between therapeutic landscape perception and health perception. When tourists perceive a high level of urbanization, it strengthens the positive impact of therapeutic landscape perception on health perception. Compared to symbolic landscapes, high urbanization has a more pronounced positive effect on natural and social landscapes. The higher the level of urbanization, the more it sustains the positive relationship between natural landscape transformation and health perception. On the one hand, due to population surges and large-scale rural-to-urban migration, urban population density and consumption continue to rise. The accelerated growth of resource consumption encourages individuals to value the organic connection between health and the environment [

65]. On the other hand, the higher the urbanization level of an individual’s residential area, the greater their preference for natural landscapes. Interacting with natural landscapes becomes an important way to reduce stress and improve mood [

66,

67]. Under the same level of urbanization perception, individuals with high social landscape perception perceive greater health benefits than those with low natural landscape perception. A positive and supportive social environment creates an emotional network where tourists can interact with other tourists and residents, gaining opportunities for learning, recreation, and creative activities [

54]. This helps balance the pressures of work and family responsibilities, thereby improving mental health [

68]. Some scholars argue that urbanization processes influence landscape patterns, ultimately leading to shifts in urban culture and individuals’ perception of landscape value. Wellness tourism brands and traditional Chinese medicine health culture jointly shape tourists’ health experiences and sense of belonging in Lintong. The unique longevity culture resonates with tourists’ inner pursuits, evoking emotional connections and enabling them to achieve psychological and spiritual well-being.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Firstly, this study constructs a model of urbanization for tourists’ perceived health, framing urbanization as a tool for enhancing individual health perception through place-based promotion. It advances understanding of human–land relationships while introducing tourism-related variables as a mediator between therapeutic landscapes and health outcomes. Unlike prior work on emotional bonds [

69,

70], this study distinguishes psychological (full mediator) and behavioral (partial mediator) involvement, highlighting the former’s critical role in health perception. This study complements this gap in the literature on tourism involvement.

Secondly, this study extends therapeutic landscape theory to Eastern contexts. While predominantly applied qualitatively in Western settings [

28,

71,

72], this study applies therapeutic landscape theory to health tourism in the Chinese context and quantitatively analyses the effective pathways for individuals to gain health perceptions from places, which provides a new research perspective for the multi-level and diversified development of therapeutic landscape theory.

Finally, this study enriches therapeutic landscape theory by demonstrating that urban tourism landscapes—comprising natural, social, and symbolic dimensions—exert differential effects, with symbolic landscapes (e.g., culturally imbued wellness motifs) more strongly shaping health perceptions. Eastern symbolic landscapes, reflecting distinct health cultures, provide new avenues for cross-cultural health tourism research.

5.2. Practical Implications

Rational planning of landscape construction. Destinations should formulate corresponding policies and planning schemes to identify and cater to individual landscape preferences, thereby enhancing the quality of landscape construction in a targeted manner. It is essential to scientifically integrate landscape elements—ensuring harmony among natural scenery, cultural features, and social ambiance—to showcase the richness and complexity of the destination’s landscapes. This approach aligns landscape development with tourists’ travel motivations and behaviors, ultimately optimizing their restorative experience. This not only applies to the Chinese context, but also provides an important reference for international destinations to utilize therapeutic landscapes for sustainable tourism development. International tourism destinations should adopt a localized approach to designing therapeutic landscapes and adopt engaged design to allow tourists to co-create meaning.

Boost tourist involvement. Since psychological involvement fully mediates health perceptions, destinations must enhance engagement through interpretive landscapes, recreational programming, and therapeutic signage. Low participation diminishes health benefits even in high-quality landscapes.

Adopt sustainable spatial planning. Urbanization’s dual effects—rapid urbanization development promotes therapeutic landscape changes to meet the needs of modern tourists on the one hand, but on the other hand, it may negatively affect natural and cultural ecosystems—require balanced landscape design: prioritize natural/social landscapes, which show stronger health linkages than symbolic ones; implement human–nature symbiosis principles [

32] to mitigate ecological damage; optimize spatial functions to support both tourist needs and ecosystem preservation. From a global perspective, therapeutic landscape planning should be incorporated as a key component in achieving sustainable tourism development goals. It is crucial to strike a balance between landscape planning and environmental conservation amidst rapid urbanization processes.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between therapeutic landscapes and individual health benefits within the context of Lintong District, several limitations in research scope, methodology, and depth should be acknowledged, warranting further exploration in future studies.

First, this study focuses on Lintong District as a case study, examining therapeutic landscapes and their health benefits from an Eastern cultural perspective and a small-scale geographical setting. Consequently, the findings may have limited generalizability. Future research should expand the scope by incorporating comparative studies across different cultural and geographical contexts, including both domestic and international case sites. Such an approach would allow for an analysis of similarities and differences in how various types of therapeutic landscapes influence individual health perceptions, thereby enhancing the theoretical depth and practical significance of the research. Additionally, the conceptualization of “health perception” involves subjective and culturally specific interpretations of therapeutic landscapes, which necessitates further in-depth exploration in subsequent studies.

Second, given the increasing societal pressures leading to rising mental health issues such as anxiety and depression among younger populations, the demographic scope of health tourism is gradually expanding, showing a trend toward younger participants. Accordingly, this study primarily surveyed individuals aged 21–40, aligning with current social trends and ensuring response accuracy. However, excluding older adults—who constitute a major participant group in health tourism—may limit the applicability of the findings. Future research should include a broader age range to yield more representative results.

Finally, this study separately examines natural, social, and symbolic landscapes. Further research should investigate their synergistic effects to develop a more comprehensive understanding of therapeutic landscapes.