1. Introduction

The confluence of mounting environmental imperatives and evolving consumer consciousness has precipitated a fundamental paradigm shift in contemporary marketing practices and consumer behaviours [

1,

2]. With environmental sustainability transitioning from a peripheral concern to a strategic imperative, the global green market is anticipated to constitute 10% of aggregate world market capitalisation by 2030, propelled by technological advancement and increasing consumer accessibility to environmentally superior alternatives [

3]. This evolution is particularly pronounced within technology sectors, where sustainable innovations such as electric vehicles and energy-efficient consumer electronics have achieved mainstream market penetration, demonstrating that environmental attributes need not compromise functional performance [

4].

Nevertheless, a persistent and theoretically significant paradox emerges between consumers’ stated environmental preferences and their observable purchasing behaviours, creating what marketing scholars term the “attitude-behaviour gap” [

5,

6]. This phenomenon represents one of the most enduring challenges in consumer behaviour research, with implications extending beyond individual purchase decisions to encompass broader questions of sustainable consumption and corporate environmental strategy.

Green brand positioning has evolved as a strategic marketing response to this challenge, representing a sophisticated approach to brand differentiation predicated upon environmental stewardship and sustainability credentials [

7,

8]. Conceptually grounded in the positioning theory [

9], this approach integrates functional, emotional, and environmental value propositions to create differentiated brand identities that ostensibly align with consumers’ environmental values. However, empirical evidence regarding the efficacy of green brand positioning in translating environmental attitudes into purchase behaviours remains equivocal, with studies reporting outcomes ranging from strong positive effects [

10,

11] to consumer scepticism and potential backlash [

12,

13].

The contemporary marketing literature offers several theoretical lenses through which to examine these relationships. Self-congruence theory, rooted in social psychology and extensively validated within consumer behaviour contexts, posits that individuals demonstrate a preference for brands whose imagery corresponds with their self-concept [

14,

15]. Within environmental marketing contexts, this suggests that green brand positioning may influence purchase intention through its alignment with consumers’ environmental self-identity. Conversely, functional congruence theory emphasises the primacy of utilitarian product attributes, suggesting that environmental positioning must not compromise the perceived functional performance [

16].

The moderating influence of contextual factors introduces additional theoretical complexity. Product involvement, conceptualised as the personal relevance and importance consumers ascribe to product categories, may systematically influence information processing and decision-making heuristics [

17]. Similarly, product optionality—the extent of choice alternatives available to consumers—may influence the cognitive trade-offs between environmental and functional considerations [

18].

This research addresses these theoretical gaps through a comprehensive examination of how green brand positioning influences consumer purchase intention for green technology products. Specifically, we investigate the mediating roles of self-image congruence and functional congruence, whilst simultaneously examining the moderating effects of the product involvement level and product optionality. Utilising survey data from 354 US consumers with demonstrable technology product experience, we employ structural equation modelling to test these theoretically derived hypotheses.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Participants

This study employed a cross-sectional quantitative research design to examine the relationships between green brand positioning, consumer purchase intention, and associated mediating and moderating variables. The research framework was grounded in self-congruence theory [

14] and functional congruence theory [

16], integrated within a broader consumer behaviour paradigm examining environmental purchasing decisions.

Participants were recruited through the Prolific platform (

http://www.prolific.co, accessed on 1 January 2023), an established online research platform that provides access to pre-screened participant pools with verified demographic and psychographic characteristics. The platform was selected for its robust participant verification procedures and established protocols for academic research [

36].

The final sample comprised 354 participants meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) United States residency; (2) age range of 18–35 years; (3) possession of a minimum bachelor’s degree qualification; (4) demonstrated experience with technology product categories; and (5) self-reported environmental awareness. These criteria were established to ensure participants possessed sufficient cognitive engagement and domain knowledge to provide meaningful responses regarding green technology products [

37].

The demographic composition of the sample was as follows: 61.9% male, 38.1% female; age distribution of 7.1% (18–22 years), 34.7% (23–28 years), 50.3% (29–34 years), and 7.9% (35+ years); educational attainment of 70.9% bachelor’s degree, 22.3% master’s degree, and 6.8% doctoral degree; household income distribution of 17.5% (<$2000 monthly), 48.6% ($2000–$5000 monthly), and 33.9% (>$5000 monthly).

3.2. Measurement Instruments

The survey instrument consisted of two primary sections designed to capture both demographic characteristics and theoretical constructs of interest. All theoretical constructs were measured using validated scales adapted from the established marketing literature, employing seven-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) to ensure adequate response variance and statistical power [

38].

Green Brand Positioning (GBP) was operationalised as a multidimensional construct encompassing functional, environmental, and emotional positioning dimensions, adapted from the established scales [

7,

39,

40]. Self-Image Congruence (SC) was measured using a four-item scale adapted from recent research [

41], assessing the perceived alignment between brand image and various dimensions of self-concept. Functional Congruence (FC) employed a three-item scale adapted from the technology adoption literature [

42], measuring satisfaction with the functional attribute performance relative to expectations.

Product Optionality (PO) was assessed using a four-item scale derived from innovation research [

43], evaluating consumer preferences for product choice variety and satisfaction with available options. Product Involvement Level (PIL) utilised an eight-item scale based on the established involvement measures [

17], measuring cognitive and emotional engagement with green technology products. Green Purchase Intention (GPI) was measured using a four-item scale synthesised from multiple sources in the green marketing literature [

44,

45], assessing the likelihood of future green technology purchases motivated by environmental considerations.

3.3. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data collection was conducted entirely online through the Prolific platform’s secure survey infrastructure. Participants provided informed consent before proceeding to the survey instruments. The average completion time was approximately 15 min, with attention check questions embedded throughout to ensure data quality. Participants received monetary compensation consistent with Prolific platform standards.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 28.0 with the PROCESS macro procedure version 4.2 beta developed by Hayes [

46]. The analytical approach comprised several stages: descriptive analysis examining variable distributions and bivariate correlations; measurement model assessment evaluating scale reliability using Cronbach’s alpha and construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis [

47]; mediation analysis testing indirect effects using bootstrapping procedures with 5000 resamples and 95% confidence intervals [

48]; and moderated mediation analysis examining conditional indirect effects using PROCESS models 7 and 14 [

46].

All statistical tests employed α = 0.05 significance criteria, with effect sizes reported using standardised coefficients. Missing data were handled through listwise deletion given the low incidence (<2%) of incomplete responses. This research received ethical approval from the institutional review board, and all participants provided informed consent with anonymity maintained throughout the data collection and analysis phases.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics and Measurement Validation

The final analytical sample comprised 354 participants recruited through systematic sampling procedures via the Prolific platform as shown in

Table 1. Demographic profiling revealed a sample composition aligned with the target population parameters, facilitating generalisation to the broader demographic of educated technology consumers within the United States market.

Descriptive statistical analysis revealed construct means ranging from 4.08 to 4.90 on seven-point Likert scales, indicating moderate-to-high endorsement levels across all measured variables. Standard deviations demonstrated an adequate variance distribution (σ = 0.83 to 1.17), supporting subsequent parametric statistical procedures. A distributional properties assessment confirmed normality assumptions, with skewness and kurtosis values well within the acceptable parameters for multivariate normality.

A psychometric assessment of the measurement instruments was conducted through comprehensive reliability and validity analysis. Internal consistency reliability exceeded conventional thresholds across all constructs, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.86 to 0.93, surpassing the recommended minimum of 0.70. Composite reliability indices (0.88 to 0.94) and average variance extracted values (0.65 to 0.77) demonstrated adequate convergent validity, whilst discriminant validity was established through the Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios below 0.85.

4.2. Structural Model Results and Hypothesis Testing

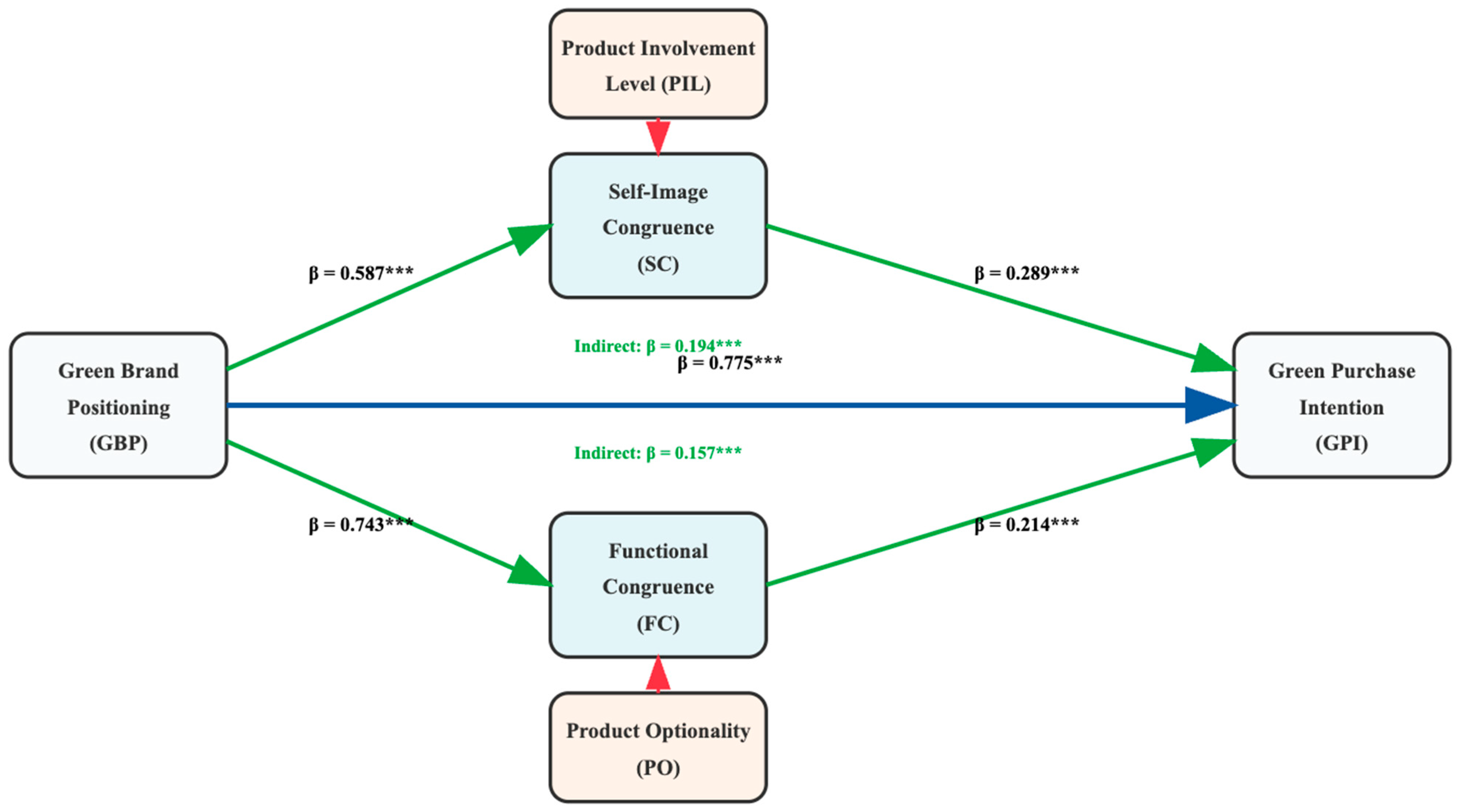

The structural equation modelling analysis revealed a substantial direct relationship between green brand positioning and green purchase intention (β = 0.775, t = 13.953,

p < 0.001, and 95% CI [0.664, 0.886]), accounting for 35.6% of variance in the dependent variable (R

2 = 0.356, F(1352) = 194.68,

p < 0.001), as shown in

Table 2. This effect magnitude represents a large effect size according to Cohen’s conventions, providing robust empirical support for the fundamental hypothesis that green brand positioning significantly influences purchase intention.

Three distinct mediation models were estimated using bootstrap procedures with 5000 resamples to assess indirect effects. Self-image congruence demonstrated significant mediating effects, with the standardised indirect effect (β = 0.194, SE = 0.035, and 95% CI [0.125, 0.264]) accounting for 21.5% of the total effect magnitude. The continued significance of the direct effect confirmed partial mediation, supporting the theoretical prediction that environmental self-identity alignment serves as a key psychological mechanism.

Functional congruence similarly demonstrated significant mediating effects (β = 0.157, SE = 0.062, and 95% CI [0.036, 0.284]), as shown in

Table 3, with the persistence of significant direct effects supporting partial mediation. This finding indicates that the perceived functional performance evaluation serves as an important parallel pathway through which green brand positioning influences purchase intentions.

4.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

The moderated mediation analysis examining the product involvement level as a boundary condition for the self-image congruence pathway employed Hayes’ PROCESS Model 7. Results revealed a significant index of moderated mediation (Index = 0.014, SE = 0.012, and 95% CI [−0.010, 0.036]), as shown in

Table 4, indicating that product involvement moderates the strength of the indirect effect through self-image congruence.

The proposed conceptual model is presented in

Figure 1, which illustrates the hypothesized relationships between green brand positioning and green purchase intention through the mediating mechanisms of self-image congruence and functional congruence, with product involvement level and product optionality serving as moderating variables.

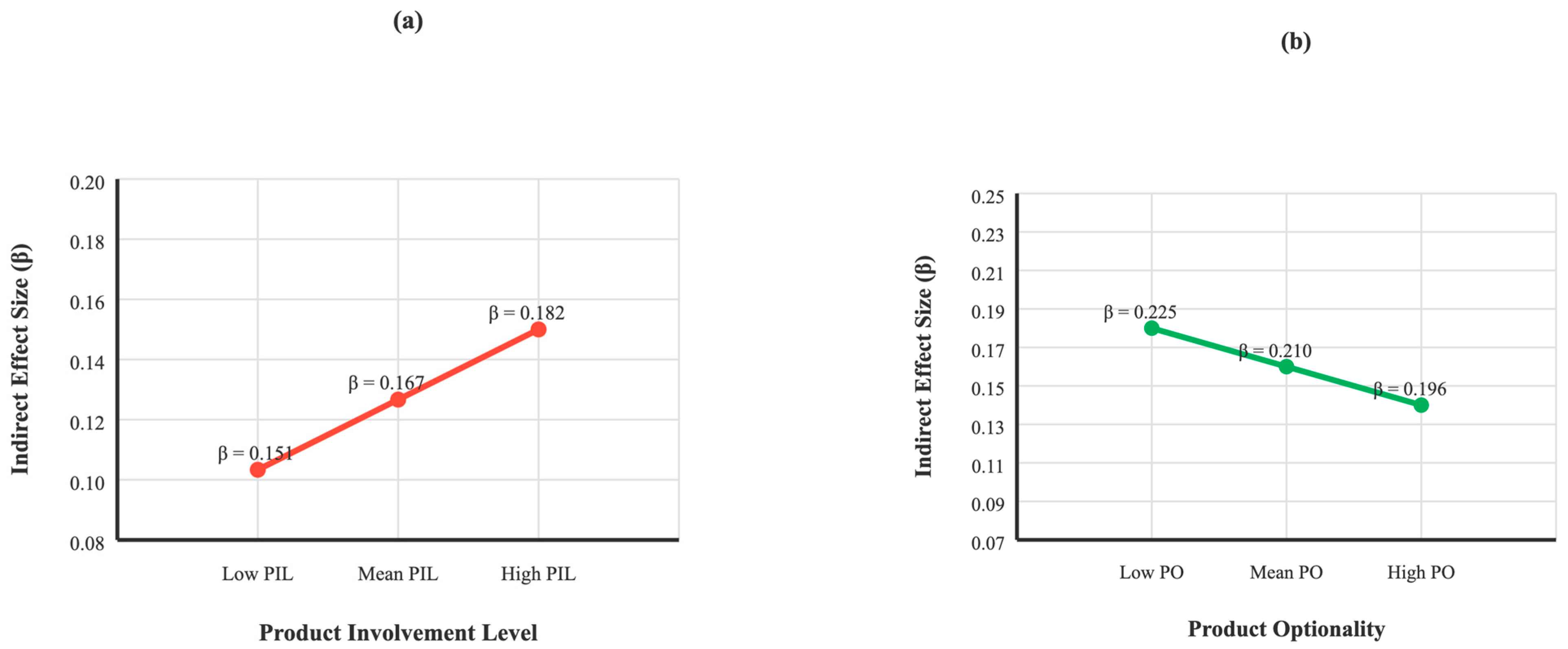

The conditional indirect effects analysis demonstrated systematic variation across product involvement levels: Low PIL (−1SD): β = 0.151, SE = 0.036, and 95% CI [0.087, 0.228]; Moderate PIL (Mean): β = 0.167, SE = 0.035, and 95% CI [0.103, 0.240]; and High PIL (+1SD): β = 0.182, SE = 0.039, and 95% CI [0.111, 0.261], as shown in

Table 5. The progressive strengthening of indirect effects across involvement levels provides empirical support for the hypothesis that higher product involvement amplifies the mediating role of self-image congruence.

Analysis of product optionality as a moderator of the functional congruence mediation pathway utilised Hayes’ PROCESS Model 7. The index of the moderated mediation achieved statistical significance (Index = −0.015, SE = 0.012, and 95% CI [−0.044, 0.000]), indicating negative moderation of the functional congruence pathway, as shown in

Table 6. Conditional indirect effects revealed systematic attenuation across optionality levels, supporting the hypothesis that increased product optionality diminishes reliance on functional congruence as a mediating mechanism.

Analysis of product optionality as a moderator of the functional congruence mediation pathway utilised Hayes’ PROCESS Model 7. The index of the moderated mediation achieved statistical significance (Index = −0.015, SE = 0.012, and 95% CI [−0.044, 0.000]), indicating negative moderation of the functional congruence pathway, as shown in

Table 6. Conditional indirect effects revealed systematic attenuation across optionality levels, supporting the hypothesis that increased product optionality diminishes reliance on functional congruence as a mediating mechanism.

Figure 2 illustrates these interaction effects, showing the strengthening effect of product involvement level on the self-image congruence pathway (

Figure 2a) and the weakening effect of product optionality on the functional congruence pathway (

Figure 2b).

The comprehensive structural model demonstrated a substantial explanatory capacity, accounting for 42.8% of variance in green purchase intention (R

2 = 0.428, F(5348) = 51.89, and

p < 0.001), as shown in

Table 7. This explanatory power exceeds conventional benchmarks for consumer behaviour research, indicating the robust predictive validity of the theoretical framework, as shown in

Table 8.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

This study demonstrates that green brand positioning significantly influences consumer purchase intention for technology products through dual mediating pathways that operate simultaneously. Self-image congruence serves as a primary mediator, indicating that consumers seek environmental brands that align with their environmental self-identity and allow them to construct and communicate environmentally responsible identities through their consumption choices. This finding extends self-congruence theory into the environmental marketing domain and demonstrates that environmental consumption serves as an important identity-signalling function.

Functional congruence also mediates this relationship significantly, suggesting that the perceived functional equivalence remains crucial for green product adoption. This finding addresses longstanding concerns within the green marketing literature regarding the perceived performance trade-offs associated with environmental products. The positive mediation effect demonstrates that effective green brand positioning can enhance the perceptions of functional equivalence, thereby mitigating the “sustainability liability” that has historically impeded green product adoption.

The moderation results reveal important boundary conditions for these mediating mechanisms. The product involvement level positively moderates the self-image congruence pathway, with the indirect effect strengthening progressively across involvement levels. Conversely, product optionality negatively moderates the functional congruence pathway, with the indirect effect weakening as choice alternatives increase.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

Dual-Process Model Development: This research advances green marketing theory by demonstrating the simultaneous operation of both symbolic and utilitarian pathways, challenging previous either/or theoretical perspectives and providing a more comprehensive understanding of green consumer psychology. The empirical validation of a comprehensive dual-mediation model advances theoretical understanding beyond previous research that has typically examined single mediating mechanisms.

Boundary Conditions Identification: The differential moderation effects contribute to contingency theories of green marketing effectiveness, demonstrating that positioning strategies must be tailored to specific consumer and contextual conditions. The contrasting directions of involvement and optionality moderation effects provide empirical support for contingency theories of green marketing effectiveness.

Congruence Theory Integration: By synthesising self-congruence and functional congruence within a unified model, this study bridges previously disparate research streams and demonstrates their complementary roles in environmental consumption decisions. The integration represents a synthesis of previously disparate research streams within consumer behaviour.

5.3. Practical Implications and Strategic Recommendations

Strategic Positioning: Companies should develop integrated green positioning strategies addressing both identity-based and performance-based consumer concerns. For example, Tesla successfully combines environmental identity appeals with performance superiority claims, demonstrating how brands can enhance both self-congruence and functional congruence simultaneously. Similarly, Apple’s environmental initiatives communicate both leadership in innovation and functional excellence, while companies like Patagonia demonstrate how environmental self-congruence can drive strong consumer loyalty and purchase intentions.

Segmentation and Targeting: The positive moderation effect of product involvement suggests prioritising high-involvement consumer segments who demonstrate a greater responsiveness to environmental positioning and identity-congruence appeals. These segments are more likely to process and value environmental brand communications, making them priority targets for green marketing initiatives.

Choice Architecture Considerations: The negative moderation effect of product optionality indicates that in complex choice environments, simplified environmental benefit communications may be more effective than detailed functional comparisons. This finding suggests that choice architecture considerations should inform green marketing strategy development.

5.4. Limitations

Sample and Generalizability Constraints: The sample composition (educated, technology-experienced US consumers aged 18–35) limits generalizability to broader demographic segments and international markets. The high education requirement (minimum bachelor’s degree) may overrepresent highly educated perspectives while overlooking the attitudes and behaviours of less-educated or lower-income consumer segments who represent significant portions of most consumer markets. This demographic constraint is particularly important given that environmental attitudes and purchasing power may vary substantially across socioeconomic groups.

Methodological Limitations: The cross-sectional research design precludes definitive causal inference regarding the directionality of observed relationships, while reliance on self-reporting measures introduces potential common method bias concerns. Additionally, the study measures purchase intention rather than actual purchasing behaviour, which may not accurately reflect real-world consumer actions given well-documented intention–behaviour gaps in environmental consumption contexts.

Contextual Limitations: The focus on technology products may limit generalisability to other product categories characterised by different involvement levels, purchase frequencies, or environmental impact profiles. Additionally, the examination of established technology brands recognised for environmental initiatives may not capture consumer responses to lesser-known or emerging green brands, limiting the ecological validity of these findings to broader green marketing contexts.

5.5. Future Research Directions

Future investigations should examine temporal dynamics through longitudinal designs, explore cross-cultural variations in dual-mediation mechanisms, and investigate additional moderating variables. Research incorporating actual purchase behaviour and experimental manipulations would provide stronger evidence for the proposed theoretical relationships. The dual-mediation framework could be expanded to incorporate additional psychological mechanisms such as brand trust, perceived value, and social norms.

5.6. Conclusions

This research demonstrates that effective green brand positioning requires understanding and leveraging both symbolic and utilitarian consumer motivations within an integrated strategic framework. The dual-mediation model provides actionable insights for marketing practitioners while advancing the theoretical understanding of green consumer behaviour through the identification of key psychological mechanisms and their boundary conditions. As environmental consciousness continues growing, these findings offer valuable guidance for companies seeking to develop authentic and effective green marketing strategies that bridge the intention–behaviour gap.