ESG Performance and Economic Growth in BRICS Countries: A Dynamic ARDL Panel Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Perspective and Framework

2.2. Previous Empirical Literature

2.3. ESG Developments in BRICS Countries

2.3.1. Brazil

2.3.2. Russia

2.3.3. India

2.3.4. China

2.3.5. South Africa

2.4. ESG Performance Indicators in BRICS

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection Procedure

3.1.1. MSCI Framework for Computing ESG Country-Level Scores

3.1.2. The MSCI Scoring Procedure

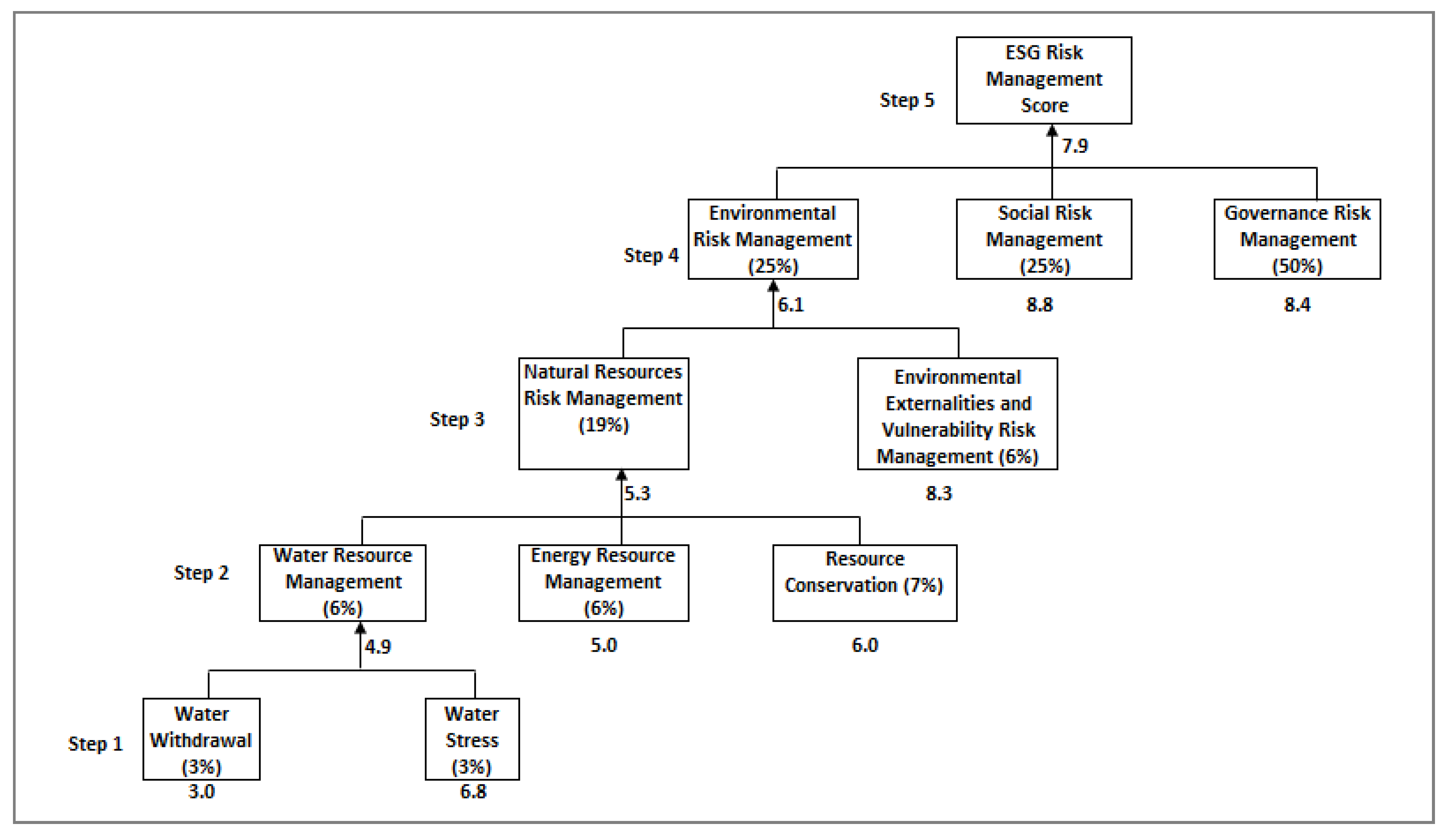

- Step 1: Water resource management: There are two indicators that constitute the 6% weight in total, namely water withdrawal (3%) and water stress (3%). The respective weights are then multiplied by the value of water withdrawal and water stress for a particular country in a given period (e.g., year) as provided in the database indicators available. For illustrative purposes, it is assumed that the weighted numeric score for water withdrawal (which should lie between 0 and 10) is 3.0 and that of water stress is 6.8, as shown in Figure 1.

- Step 2: The water resource management sub-factor score, which is 4.9, is determined by taking the simple average of these two scores under Step 1. Similar calculations are made for the numerical scores for the other sub-factors, i.e., resource conservation (6.0) and energy resource management (5.0).

- Step 3: The weighted average score of the three sub-factors (resource conservation, water resource management, and energy resource management) yields a score of 5.3 for the risk factor management score, or in this case, natural resources risk management. The environmental externalities and vulnerability risk is another risk factor within the environmental pillar, and its risk factor management score is computed in a similar manner (8.3).

- Step 4: The weighted average of the environmental externalities and vulnerability risk score with the natural resource risk management score yields the environmental risk management score of 6.1. Similar calculations are used to produce the social risk management score (8.8) and the governance risk management score (8.4).

- Step 5: The ultimate ESG risk management score (7.9) is computed as the weighted average of the environmental risk management, social risk management, and governance risk management scores.

3.2. The Empirical Model

- denotes the log of real GDP per capita for country at year ;

- represents the ESG country score for country at year ;

- represents the carbon emissions (CO2) score in metric tons per capita, serving an environmental proxy for country at year ;

- is the annual percentage inflation rate (consumer prices) for country at year ;

- represents net inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) as a percentage of GDP for country at year ;

- is the trade (sum of exports and imports over GDP) for country at year ;

- represents the error correction term (ECT) or drift term, variables with coefficients , are the model’s short-run coefficients, while are the long-run coefficients.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Panel Unit Root Tests

4.4. Cointegration Test

4.5. Optimal Lag Length

4.6. Estimation of the ARDL Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Galindo, L.S.; Samaniego, J. The Economics of Climate Change in Latin America and the Caribbean: Stylized Facts. Cepal Rev. 2010, 100, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribando, J.M.; Bonne, G. A New Quality Factor: Finding Alpha with ASSET4 ESG Data; Starmine Research Note; Thomson Reuters: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI). Annual Report 2018. Available online: https://d8g8t13e9vf2o.cloudfront.net/Uploads/g/f/c/priannualreport_605237.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Financial Outperformance; Smith School of Enterprise: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, B. Keeping Ethical Investment Ethical: Regulatory Issues for Investing Sustainably. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaye, M.A.; Ho, S.H.; Oueghlissi, R. ESG Performance and Economic Growth: A Panel Co-integration Analysis. Empirica 2022, 49, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Isaac, D.; Evaggelinos, K. Revisiting the National Corporate Social Responsibility Index. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GRI and Sustainability Reporting. 2019. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Tripathi, V.; Kaur, A. Socially Responsible Investing: Performance Evaluation of BRICS Nations. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020, 17, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Foreign Direct Investment Inflows. 2015. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.CD.WD (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Wentworth, L.; Oji, C. The Green Economy and the BRICS Countries: Bringing Them Together. Occas. Pap. 2013, 170, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, A.; Griek, A.; Jansen, C. Bridging the Gaps: Effectively Addressing ESG Risks in Emerging Markets; Sustainalytics: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.E.; Jones, C.I. Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output per Worker Than Others? Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 385–472. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.R.; Kitenge, E.; Bedane, B. Government Effectiveness and Economic Growth. Econ. Bull. 2017, 37, 222–227. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, W. A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policies; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, M. Green Growth. In The Handbook of Global Climate and Environment Policy; Falkner, R., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cracolici, M.; Cuffaro, M.; Nijkamp, P. The Measurement of Economic, Social and Environmental Performance of Countries: A Novel Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 95, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S.; Wares, A.; Orzell, S. The Relationship Between Social Progress and Economic Development; Methodological Report; Social Progress Index 2015. Available online: https://www.truevaluemetrics.org/DBpdfs/Metrics/SPI/Social-Progress-Index-2015-Methodology-Report.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Zhong, R. Country Environmental, Social and Governance Performance and Economic Growth: The International Evidence. Account. Financ. 2023, 63, 3911–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Kallis, G.; Martinez-Alier, J. Crisis or Opportunity? Economic Degrowth for Social Equity and Ecological Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtin, F.; De Serres, A.; Alexander, H. The Ins and Outs of Unemployment: The Role of Labour Market Institutions; OECD Economics Department Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Howarth, R. Sustainability, Well-Being, and Economic Growth. Mind. Nat. 2012, 5, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty, D.; Mandal, S. Estimating the Relationship Between Economic Growth and Environmental Quality for the BRICS Economies—A Dynamic Panel Data Approach. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 19–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G.; Romer, D.; Weil, D.N. A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. An African Success: Botswana. In Analytic Development Narratives; Rodrik, D., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Algarhi, A.; Karimazondo, L. Exploring the Link between ESG Performance and Economic Growth in the BRICS+ Countries: Evidence from a Nonlinear ARDL Approach. Telemat. Inform. 2024, 87, 102215. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidis, D.; Bouri, E.; Koulakiotis, A.; Mefteh-Wali, S. Does ESG Performance Predict Future Economic Activity? A Global Analysis. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2024, 87, 101001. [Google Scholar]

- Ererdi, E.; Güneren Genç, Y. Short-Term Costs and Long-Term Benefits of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Activities: Evidence from Emerging Markets. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sredojević, D.; Cvetanovic, S.; Gorica, B. Technological Changes in Economic Growth Theory: Neoclassical, Endogenous, and Evolutionary-Institutional Approach. Econ. Themes 2016, 54, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M.; Swan, T.W. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. J. Polit. Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. On the Mechanics of Economic Development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dong, Z.; Li, R. Revisiting Renewable Energy and Economic Growth—Does Trade Openness Matter? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 31727–31740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, P.; Van Den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Evolutionary Economic Theories of Sustainable Development. Growth Change 2001, 32, 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 1955, 45, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, T. Empirical Tests and Policy Analysis of Environmental Degradation at Different Stages of Economic Development; Working Paper WP238; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Green Growth and Developing Countries: A Summary for Policy Makers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Mendelsohn, M.A.; Eichenbaum, M. A Quantitative Review of the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production. N. Y. Rev. Books 2001, 48, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Crifo, P.; Forget, V.D. The Economics of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Firm-Level Perspective Survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2015, 29, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwartney, J.D.; Holcombe, R.G.; Lawson, R.A. Economic Freedom, Institutional Quality, and Cross-Country Differences in Income and Growth. Cato J. 2004, 24, 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M. Corruption’s Direct Effects on Per-Capita Income Growth: A Meta-Analysis. J. Econ. Surv. 2014, 28, 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Naidu, S.; Restrepo, P.; Robinson, J.A. Democracy Does Cause Growth. J. Polit. Econ. 2019, 127, 47–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemli-Ozcan, S. Does the Mortality Decline Promote Economic Growth? J. Econ. Growth 2002, 7, 411–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, M.; Forster, D.; King, K. Cost-Benefit Analysis for the Protocol to Abate Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground Level Ozone in Europe; Working Paper; AEA Technology: Oxon, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Halter, D.; Oechslin, M.; Zweimüller, J. Inequality and Growth: The Neglected Time Dimension. J. Econ. Growth 2014, 19, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D. Government, Geography, and Growth: The True Drivers of Economic Development. Foreign Aff. 2012, 91, 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Lissovolik, Y. ESG and the BRICS: Sustainability as a Platform for South-South Cooperation. Valdai Discussion Club Report. July 2021. Available online: https://valdaiclub.com (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Zhou, X.; Caldecott, B.; Harnett, E.; Schumacher, K. The Effect of Firm-Level ESG Practices on Macroeconomic Performance; Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment Working Paper 20-03; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğmuş, M.; Gülay, G.; Ergun, K. Impact of ESG Performance on Firm Value and Profitability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22 (Suppl. S2), S119–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis: A Survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeotti, M.; Lanza, A.; Pauli, F. Reassessing the Environmental Kuznets Curve for CO2 Emissions: A Robustness Exercise. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. Does increasing investment in research and development promote economic growth decoupling from carbon emission growth? An empirical analysis of BRICS countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, F. Does ESG Performance Boost Firm Value? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2594. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos, A. Social Protection for the Poor and Poorest: Concepts, Policies and Politics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Yakovlev, P. State capacity, sustainable development, and the G20’s emerging economies. World Dev. 2017, 98, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, L. Public Investment and Inclusive Growth in India. Econ. Political Wkly. 2020, 55, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nattrass, N. Class, Race, and Inequality in South Africa; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Rodríguez-Rosa, M.; Vicente-Galindo, P. Are Worldwide Governance Indicators Stable or Do They Change over Time? A Comparative Study Using Multivariate Analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B. Governance in BRICS: Governance Quality and Its Impact on Emerging Markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello, L.; Tiongson, E.R. Strengthening Governance for Investment and Growth in Emerging Markets. OECD Development Matters Blog. 26 April 2021. Available online: https://oecd-development-matters.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Victor, P.A. Managing Without Growth: Slower by Design, Not Disaster; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, R.H.; Levine, A.S.; Dijk, O. Interdependent Preferences and the Regulation of Competitive Relativism. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2005, 57, 391–405. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, J.K. Is Inequality Bad for the Environment? Res. Soc. Probl. Public Policy 2010, 18, 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Hasan, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder’s Value: An Event Study Analysis. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2014, 24, 961–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pontes, N. Europe Carmakers Linked to Amazon Destruction: Report DW. 16 April 2021. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/amazon-rainforest-european-car-manufacturers-linked-to-illegal-deforestation-says-report/a-57225234 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Shinde, M. Globalization, Environmental Law, and Sustainable Development in the Global South; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, T. Latin America: Gender Gap Index 2022 by Country. Statista, 1 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.A.C.; Queirós, A.S.S. Economic Growth, Human Capital and Structural Change: A Dynamic Panel Data Analysis. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1636–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azahaf, N.; Schraad-Tischler, D. Governance Capacities in the BRICS; Sustainable Governance Indicators; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Centre of Government Review of Brazil: Toward an Integrated and Structured Centre of Government; OECD Public Governance Reviews; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Noguti, V.; Yogui, R. ESG and the Circular Economy in Brazil. June 2021, pp. 1–3. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://ecoawordpress.usuarios.rdc.puc-rio.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ESG-and-the-Circular-Economy-in-Brazil-1.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjmgeLvgqiOAxXRr1YBHYrZMsIQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1G0BEP0xBsLb9GnvF9MGau (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Duarte, M. The Power of the Consumer in the New Face of Business—The Impact of ESG on the Business Environment, Consumption and Finance. Veja Magazine. Available online: https://veja.abril.com.br/insights-list/a-nova-face-dos-negocios-o-impacto-do-esg-no-ambiente-empresarial-no-consumo-e-nas-financas/ (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Arnell, N.W.; Lowe, J.A.; Challinor, A.J.; Osborn, T.J. Global and Regional Impacts of Climate Change at Different Levels of Global Temperature Increase. Clim. Change 2019, 155, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijevic, M.; Crespo Cuaresma, J.; Muttarak, R.; Schleussner, C.-F. Governance in Socioeconomic Pathways and Its Role for Future Adaptive Capacity. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Russian Federation 2013; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smorgunov, L.V. Inclusive Growth and Administrative Reform in the BRICS Countries. Public Adm. Issues 2018, 5, 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Transparency. Report Comparing G20 Climate Action and Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://www.climate-transparency.org (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Mitrova, T.; Yermakov, V. Russia’s Energy Strategy-2035: Struggling to Remain Relevant; IFRI: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, V. Peaking and Net-Zero for India’s Energy Sector CO2 Emissions: An Analytical Exposition; Council on Energy, Environment and Water: New Delhi, India, 2021; Available online: https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/ceew-study-on-how-can-india-reach-net-zero-emissions-target.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Civil Panda. Good Governance, Principles and Initiatives in India. 14 October 2022. Available online: https://civilpanda.com/good-governance-principles-initiatives-in-india/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Gupta, E.; Rangaswamy, A. The Importance of “ESG” and Its Application in India. Lexforti Legal J. 2021, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Inamdar, M.M.; Rachchh, M.A. Advent of ESG Ecosystem in India. Manag. Account. J. 2022, 57, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A. Preparing India for Extreme Climate Events: Mapping Hotspots and Response Mechanisms; Council on Energy, Environment and Water: New Delhi, India, 2020; Available online: https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/CEEW-Preparing-India-for-extreme-climate-events_10Dec20.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Schulz, M.S. Inequality, Development, and the Rising Democracies of the Global South. Curr. Sociol. Monogr. 2015, 63, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Panday, P.; Dangwal, R. Determinants of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) Disclosure: A Study of Indian Companies. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2020, 17, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. China in Focus: Lessons and Challenges; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/countries/china-people-s-republic-of.html (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Lu, M. Visualizing All the World’s Carbon Emissions by Country. Visual Capitalist. 8 November 2023. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Advancing the Green Development of the Belt and Road Initiative: Harnessing Finance and Technology to Scale up Low Carbon Infrastructure; World Economic Forum and PwC China, Insight Report; World Economic Forum (WEF): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Employment Outlook; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jütting, J.; de Laiglesia, J.R. Is Informal Normal? Towards More and Better Jobs in Developing Countries; OECD Development Centre, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Manion, M. Taking China’s Anticorruption Campaign Seriously. Econ. Polit. Stud. 2016, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). China’s Approach to Global Governance. 2023. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/china-global-governance/ (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). AIIB Launches Sustainable Development Bond Framework; Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: https://www.aiib.org/en/news-events/news/2021/AIIB-Launches-Sustainable-Development-Bond-Framework.html (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- World Bank. Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Akinbami, O.M.; Oke, S.R.; Bodunrin, M.O. The State of Renewable Energy Development in South Africa: An Overview. Alexandria Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5077–5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, F.; Steenkamp, A. Building an Inclusive Social Protection System in South Africa; OECD Economics Department Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; No. 1620. [Google Scholar]

- Government Communication and Information System (GCIS). Education: 1994–2016. South Africa 2016/17 Yearbook; Government Communication and Information System: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- The Presidency. Statement by President Cyril Ramaphosa at the Handover of the First Part of the State Capture Commission Report. In Media Statement; The Presidency: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, L. Health Infrastructure and Inclusive Growth in India. Econ. Political Wkly. 2020, 55, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Social Protection in South Africa and Brazil: Comparative Policy Review; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2022: BRICS Focus. 2023. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022 (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. Sustainable Development Report 2022; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MSCI (Morgan Stanley Capital International). MSCI ESG Government Ratings Methodology; MSCI ESG Research LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi, B. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L.; Chanda, A.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Sayek, S. FDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Local Financial Markets. J. Int. Econ. 2014, 64, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztein, E.; De Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.W. How Does FDI Affect Economic Growth? J. Int. Econ. 2013, 45, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrios, A.; Hall, S. Applied Econometrics: A Modern Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan-Ming, L.; Kuan-Min, W. How Do Economic Growth Asymmetry and Inflation Expectation Affect Fisher Hypothesis and Fama’s Proxy Hypothesis? J. Quant. Financ. Econ. 2017, 1, 428–453. [Google Scholar]

- Akinlo, O.O.; Olayiwola, J.A. Dividend Policy-Performance Nexus: PMG-ARDL Approach. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samargandi, N.; Fidrmuc, J.; Ghosh, S. Is the Relationship Between Financial Development and Economic Growth Monotonic? Evidence from a Sample of Middle-Income Countries; CESifo Working Paper No. 4743; CESifo: Munich, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, H.; Smith, R. Estimating Long-Run Relationships from Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.P. Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.; Shin, Y. An Autoregressive Distributed Lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration in Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century; The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Volume 4, pp. 371–413. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 6th ed.; Cenage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, D. Dimensional Analysis and Logarithmic Transformations in Applied Econometrics. Univ. Mass. Amherst Econ. Dep. Work. Pap. Ser. 2022, 339, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.K.; Goes, J. Dissertation and Scholarly Research: Recipes for Success; Dissertations Success LLC.: Seattle, WA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, H.; Shin, Y. Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, S.; Schneider, D.C. ARDL: Estimating Autoregressive Distributed Lag and Equilibrium Correction Models. Stata J. 2023, 23, 983–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Critical Values for Cointegration Tests in Heterogeneous Panels with Multiple Regressors. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999, 61, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. Testing for Panel Cointegration with Multiple Structural Breaks. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2006, 68, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 3rd ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftery, A.E. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. In Sociological Methodology; Marsden, P.V., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1995; Volume 25, pp. 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, K.; Nagy, D.K.; Rossi-Hansberg, E. The Geography of Development. J. Polit. Econ. 2018, 126, 903–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Crifo, P.; Diaye, M.-A.; Oueghlissi, R.; Scholtens, B. Sovereign Bond Yield Spreads and Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis of OECD Countries. J. Bank. Financ. 2019, 98, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delova-Jolevska, E.; Ilievski, A.; Jolevski, L.; Csiszárik-Kocsir, Á.; Varga, J. The Impact of ESG Risks on the Economic Growth in the Western Balkan Countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, S.S.; Bekun, F.V.; Barua, S. The role of environmental sustainability and institutional quality in the economic growth of MINT countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 25352–25362. [Google Scholar]

- Nathaniel, S.; Adeleye, N.; Hassan, S. Environmental quality and economic growth in G20 countries: A dual threshold analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Saud, S.; Sadiq, M.; Jamil, R. Environmental Emissions in G20 Nations: The Dynamics of Economic Growth, Globalization, and Capital Formation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 21541–21559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. Sustainability Disclosure for Container Shipping: A Textmining Approach. Transp. Policy 2021, 110, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ozturk, I.; Khan, A. Dynamic linkages between environmental regulation, ESG performance, and economic growth in G20 countries. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Narayan, S. Carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth: Panel data evidence from developing countries. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDESA (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs). Economic and Social Challenges and Opportunities; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/RECOVER_BETTER_0722-1.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Nyamongo, E.M.; Misati, R.N.; Kipyegon, L.; Ndirangu, L. Remittances, financial development and economic growth in Africa. J. Econ. Bus. 2012, 64, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshikoya, T.W. Macroeconomic Determinants of Domestic Private Investment in Africa: An Empirical Analysis. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1994, 42, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, S.; Bick, A.; Nautz, D. Inflation and growth: New evidence from a dynamic panel threshold analysis. Empir. Econ. 2013, 44, 861–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.J.; Haacker, M.; Lee, K.; Le Goff, M. Determinants and Macroeconomic Impact of Remittances in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Afr. Econ. 2010, 20, 312–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadebo, A.D.; Mohammed, N. Monetary policy and inflation control in Nigeria. J. Ecol. Sustain. 2015, 6, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, S.; Hoeffler, A.; Temple, J. GMM Estimation of Empirical Growth Models; C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers No. 3048; University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brueckner, M.; Lederman, D. Trade Openness and Economic Growth: Panel Data Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Economica 2015, 82, 1302–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burange, L.G.; Ranadive, R.R.; Karnik, N.N. Trade Openness and Economic Growth Nexus: A Case Study of BRICS. Foreign Trade Rev. 2019, 54, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hye, Q.M.; Wizarat, S.; Lau, W.Y. The Impact of Trade Openness on Economic Growth in China: An Empirical Analysis. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2016, 3, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchet, M.; Le Mouël, C.; Vijil, M. The Relationship between Trade Openness and Economic Growth: Some New Insights on the Openness Measurement Issue. World Econ. 2018, 41, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, M.; Teal, F. Productivity Analysis in Global Manufacturing Production; Economics Series Working Papers 515; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| ESG Dimension | Representative Studies | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | [57,59,60] | EKC observed in parts of BRICS; decoupling is not uniform |

| Social | [61,63] | Social investments support growth, but inequality moderate effects |

| Governance | [66,67] | Strong institutions enhance growth; BRICS show uneven governance performance |

| Counterarguments | [69,71,73] | ESG stringency may constrain growth in the short term |

| Variable (Code) | Description | Source(s) | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real GDP per capita (GDPpc) | A measure of a country’s economic output per person | World Development Indicators (WDIs) | |

| Country ESG score (ESG) | A measure of how well risks and concerns related to environmental, social, and governance issues are addressed in a country. | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), the World Inequality Database (WID), the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), Vision of Humanity (VOH), Transparency International (TI) | Positive and negative |

| Carbon emissions (CO2) | Carbon dioxide produced during the consumption of solid, liquid, and gas fuels and gas flaring | Climate Watch, World Development Indicators (WDIs), World Population Review | Positive and negative |

| Foreign direct investment (FDI) | An ownership stake in a foreign company or project from another country made by an investor, company, or government | World Development Indicators (WDIs), International Monetary Fund (IMF) | Positive and negative |

| Inflation (INFL) | The rate of increase in prices over a given period measured by the consumer price index. | World Development Indicators (WDIs), International Monetary Fund (IMF) | Positive and negative |

| Trade openness (OPEN) | The extent to which a country is engaged in the global trading system, measured as the sum of a country’s exports and imports as a share of that country’s GDP (in %). | World Development Indicators (WDIs) | Positive |

| ESG Rating | Country ESG Score Zone |

|---|---|

| AAA | |

| AA | |

| A | |

| BBB | |

| BB | |

| B | |

| CCC |

| Descriptive Statistics | lnGDPpc | ESG | CO2 | INFL | FDI | OPEN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Min | 6.63 | 3.26 | 0.883 | −0.732 | 0.205 | 22.11 |

| Max | 9.25 | 6.17 | 11.88 | 21.48 | 5.37 | 68.09 |

| Median | 8.73 | 4.72 | 6.08 | 5.18 | 2.07 | 46.52 |

| Mean | 8.47 | 4.71 | 5.60 | 5.98 | 2.29 | 44.25 |

| Std. dev | 0.761 | 0.672 | 3.79 | 4.04 | 1.24 | 11.99 |

| Variance | 0.579 | 0.452 | 14.36 | 16.28 | 1.55 | 143.7 |

| Skewness | −1.133 | −0.174 | 0.246 | 1.38 | 0.308 | −0.313 |

| Kurtosis | 2.93 | 2.72 | 1.59 | 5.72 | 2.15 | 2.04 |

| Jarque–Bera Chi(2) | 3.625 0.1632 | |||||

| Variables | lnGDPpc | ESG | CO2 | INFL | FDI | OPEN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnGDPpc | 1.0000 | |||||

| ESG | −0.6336 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| CO2 | 0.5950 *** | −0.3252 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| INFL | 0.0634 | 0.1549 | 0.2527 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| FDI | 0.1927 ** | −0.0760 | −0.1769 * | −0.0552 | 1.0000 | |

| OPEN | −0.0506 | 0.1015 | 0.5914 *** | 0.2762 *** | −0.1699 * | 1.0000 |

| Variables | Level | LLC | IPS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Statistic | p-Value | t-Statistic | p-Value | ||

| lnGDPpc | I(0) | −4.8504 | 0.0001 | −2.6389 | 0.0042 |

| ESG | I(1) | −5.4599 | 0.0000 | −5.6897 | 0.0000 |

| CO2 | I(1) | −2.2814 | 0.0113 | −2.6083 | 0.0045 |

| INFL | I(0) | −3.1436 | 0.0008 | −2.8737 | 0.0020 |

| FDI | I(0) | −1.9351 | 0.0265 | −2.0843 | 0.0186 |

| OPEN | I(1) | −2.865 | 0.0021 | −3.6849 | 0.0001 |

| Pedroni Test | Westerlund Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Statistic | p-Value | Hypothesis | Statistic | p-Value |

| Modified Phillips–Perron t | 2.5920 *** | 0.0048 | Some panels are cointegrated | 2.1082 ** | 0.0175 |

| Phillips–Perron t | 1.0064 | 0.1571 | : All panels are cointegrated | 1.0562 | 0.1454 |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | 1.0163 | 0.1547 | |||

| forval i = 1/5 { ardl lnGDPpc ESG CO2 INFL FDI OPEN if (cy == ‘i’), maxlag(1 1 1 1 1 1) matrix list e(lags) di } | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | lnGDPpc | ESG | CO2 | INFL | FDI | OPEN |

| Country 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Country 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Country 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Country 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Country 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Optimal lag | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Long-run | ||

| ESG | 0.167 ** | 0.0657 |

| CO2 | 0.126 ** | 0.0569 |

| INFL | −0.0303 *** | 0.00897 |

| FDI | 0.00747 | 0.0182 |

| OPEN | 0.0131 * | 0.00729 |

| Short-run | ||

| ECT | −0.105 *** | 0.0296 |

| D1.ESG | −0.00518 * | 0.00283 |

| D1.CO2 | 0.0735 ** | 0.0364 |

| D1.INFL | 0.00108 | 0.00174 |

| D1.FDI | 0.00180 | 0.00485 |

| D1.OPEN | −0.000432 | 0.000784 |

| Intercept | 0.754 *** | 0.232 |

| Countries | 5 | |

| Observations | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manjengwa, E.; Dunga, S.H.; Mncayi-Makhanya, P.; Makhalima, J. ESG Performance and Economic Growth in BRICS Countries: A Dynamic ARDL Panel Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146334

Manjengwa E, Dunga SH, Mncayi-Makhanya P, Makhalima J. ESG Performance and Economic Growth in BRICS Countries: A Dynamic ARDL Panel Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146334

Chicago/Turabian StyleManjengwa, Earnest, Steven Henry Dunga, Precious Mncayi-Makhanya, and Jabulile Makhalima. 2025. "ESG Performance and Economic Growth in BRICS Countries: A Dynamic ARDL Panel Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146334

APA StyleManjengwa, E., Dunga, S. H., Mncayi-Makhanya, P., & Makhalima, J. (2025). ESG Performance and Economic Growth in BRICS Countries: A Dynamic ARDL Panel Approach. Sustainability, 17(14), 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146334