The Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Development in Guided Role-Playing Simulations for Sustainable Pre-Service Teacher Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Need for Teacher Simulation

1.2. Impact of Proficiency and Interest on Simulation Outcomes

1.3. Research Questions

- Do different efficacy levels (high, middle, low) lead to distinct overall patterns of interest development during the simulation?

- Do efficacy levels differentially affect interest scores at each of the four phases of interest development?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Simulating Classroom Management

2.2. Role-Playing Simulation for Strategic Guidance

2.3. Engagement in Simulation

2.4. Design of Classroom Management Simulations

- Individual Interest I (emerging individual interest) transitions from situational interest to a more personal connection with the topic. The simulation design strategically creates meaningful and relevant connections between the content and the learner, fostering a personal inclination to further engage with the subject matter [65].

- Individual Interest II (well-developed individual interest) represents the culmination of this progression where the interest becomes a stable and enduring part of the individual’s preferences and drives consistent engagement over time. Simulation strategies in this phase involve sophisticated educational techniques, such as project-based learning and personalized tutoring, to deepen understanding and commitment to the topic [57,66,67].

| Phase of Interest Development | Situational Interest I (Triggered Situational Interest) | Situational Interest II (Maintained Situational Interest) | Individual Interest I (Emerging Individual Interest) | Individual Interest II (Well-Developed Individual Interest) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Psychological state resulting from short-term changes in cognitive and affective processing associated with a particular class of content. | Psychological state that involves focused attention to a particular class of content that reoccurs and/or persists over time. | Psychological state involving the beginning of a relatively enduring predisposition to seek re-engagement with a particular class of content over time. | Psychological state involving a relatively enduring predisposition to reengage a particular class of content over time. |

| Simulation design | Emotional appeal to users with vivid, visceral, and first-hand experience. Afford users novelty and exploration intention resulting in senses of presence, motivation, interest, or engagement. [55,61,62] | Require users to engage in learning activities continuously. Enhance the positive effect, focused attention, and exploration intention to further fulfill triggered situational interest. [63,64] | Organize the content to create meaningful connections between users and simulation. Present the content/tasks that users find relevant and meaningful to them Reinforce situational interest through new instructional events. [54,65] | Create understanding-conducive environments such as project-based learning, cooperative group work, and one-on-one tutoring [57,66,67]. |

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Guided Role-Playing Simulation

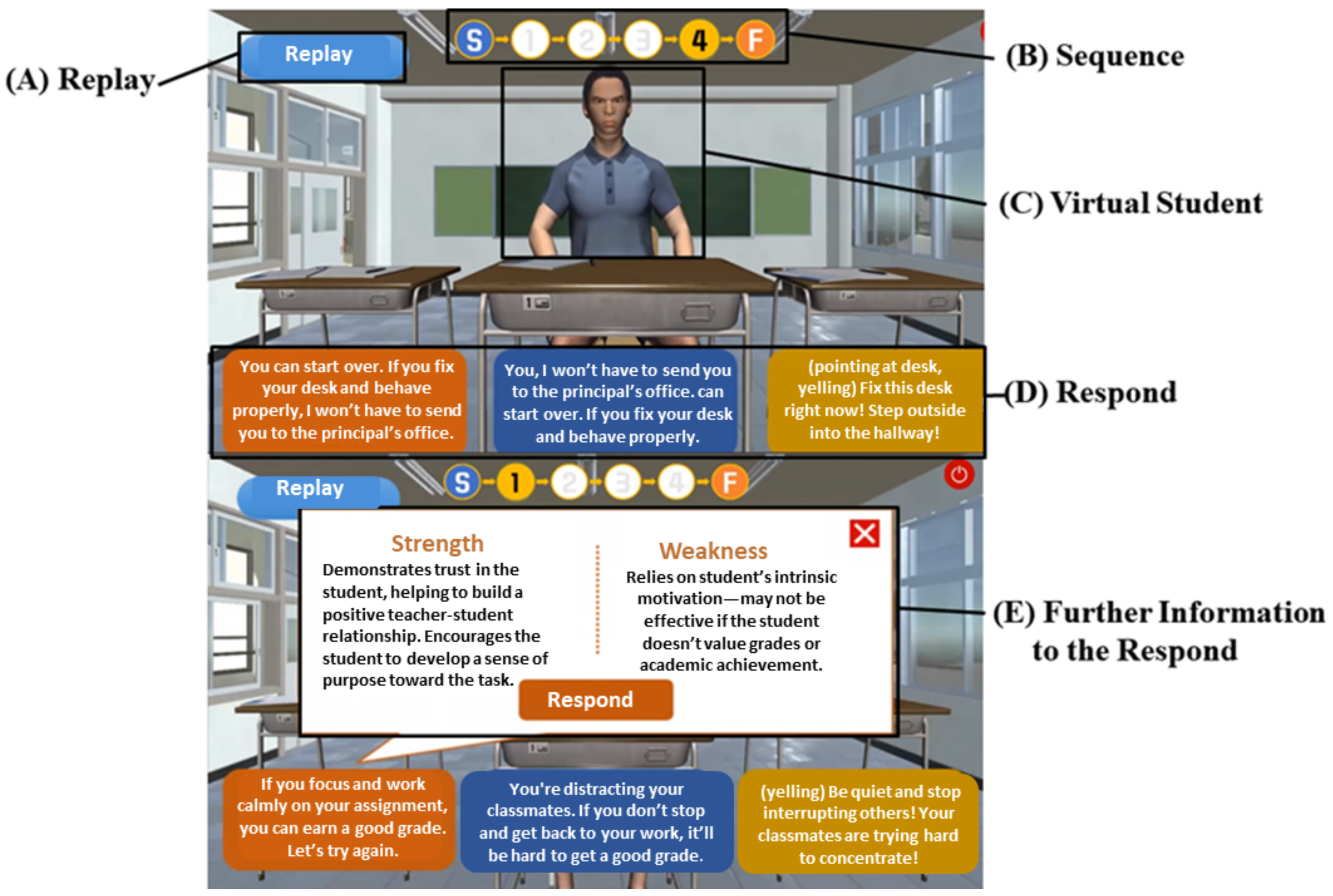

- Replay: Participants can observe the virtual student’s behavior and reactions using the replay menu (Figure 1A).

- Sequence: The simulation progresses through six sequences, starting with S (Start) and ending with F (Finish). The entire conversation between the participant and the virtual student follows four steps (indicated by 1, 2, 3, and 4 between S and F). The current sequence is indicated with an orange circle, allowing participants to intuitively see which part of the conversation they are in. For example, the conversation sequence in Figure 1 shows sequence 1 (Figure 1B).

- Virtual student: The virtual students verbally and physically respond to participants’ comments and questions. The virtual student avatar displays authentic student looks and gestures that provide contextual cues for the conversation (Figure 1C).

- Respond: Participants can choose one of the three responses developed based on DeJong et al. [21] and Lewis [68]. In Figure 1, the text in the brown box on the left reflects reward strategies, “You will get a good score if you do the assignment well. Let’s try again.” The text in the blue box in the middle reflects punishment strategies, “You won’t get a good score if you disturb other friends’ studies.” The text in the golden box on the right represents aggressive responses toward the virtual student, “(Yelling) Be quiet and don’t disturb your friends!” (Figure 1D).

- Further information to the response: When the participant selects one of the responses, additional information is provided, explaining the advantages and disadvantages of that response as a classroom management technique. For example, if the reward strategy is chosen, a pop-up message displays the advantages and disadvantages of the selected strategy (advantages: a positive relationship with the student can be maintained by demonstrating trust in the student and providing the student with a sense of purpose for the assignment; disadvantages: this may be ineffective if the student does not value scores since it focuses on student autonomy). This information helps participants reflect on whether their response is appropriate for the given simulated problem (Figure 1E).

3.4. Measures

- Triggered Situational Interest (TSI; 5 items): Focuses on spontaneous focused attention and affective reactions to the materials presented.

- Maintained Situational Interest (MSI; 5 items): Represents how meaningful the materials are and to what extent the triggered interest persisted.

- Individual Interest (EII; 7 items): Characterized by positive feelings, stored knowledge and stored value.

- Well-Developed Individual Interest (WII; 7 items): Indicates long-term stored knowledge and value.

3.5. Procedures

3.6. Reasarch Design and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Development

4.2. Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Among the Four-Phase of Interest Development

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Classroom Management Efficacy and Interest Development in a Guided Role-Playing Simulation

5.2. Patterns of Interest Development Within a Guided Role-Playing Simulation

5.3. Limitation

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poznanski, B.; Hart, K.C.; Cramer, E. Are teachers ready? Preservice teacher knowledge of classroom management and ADHD. Sch. Ment. Health 2018, 10, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Academic Surgical Administrators (Spaces4learning). 14 February 2019. Educators Report Growing Behavioral Issues Among Young Students. Available online: https://spaces4learning.com/Articles/2019/02/14/Student-Behavior.aspx (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Hyun, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, E.; Seo, C.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S. Development Research of a Step-by-Step Guidance Manual on Student Problem Behavior in Schools by Field Teachers. J. Res. Educ. 2024, 37, 173–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, G.; McGilloway, S.; Hyland, L.; Leckey, Y.; Kelly, P.; Bywater, T.; O’Neill, D. Exploring the effects of a universal classroom management training programme on teacher and child behaviour: A group randomised controlled trial and cost analysis. J. Early Child. Res. 2017, 15, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, C.; Lentillon-Kaestner, V.; Pasco, D. Students’ individual interest in physical education: Development and validation of a questionnaire. Scand. J. Psychol. 2021, 62, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidić, T. Student classroom misbehavior: Teachers’ perspective. Croat. J. Educ. 2022, 24, 599–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Han, I. Teachers’ Professional Development Needs for Student Behavior and Classroom Management: A Comparative Analysis of South Korea and Four OECD Countries Using PISA 2022 Data. J. Korean Teach. Educ. 2024, 41, 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council on Teacher Quality. NCTQ Teacher Prep Review 2014. Available online: https://www.nctq.org/publications/Teacher-Prep-Review-2014-Report (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Cohen, E.; Hoz, R.; Kaplan, H. The practicum in pre-service teacher education: A review of empirical studies. Teach. Educ. 2013, 24, 345–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadjanova, N. Effective classroom management techniques for curriculum of 21st century. Sci. Educ. 2020, 1, 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, A.; McKenna, J.W.; Haring, C.D. Behavior and classroom management: Are teacher preparation programs really preparing our teachers? Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 2017, 61, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Yoo, J.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, H.; Zeidler, D.L. Enhancing students’ communication skills in science classroom through socioscientific issues. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2016, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Hammerness, K.; McDonald, M. Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2009, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A. Situated learning theory and the pedagogy of teacher education: Towards an integrative view of teacher behavior and teacher learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieker, L.A.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Lignugaris/Kraft, B.; Hynes, M.C.; Hughes, C.E. The potential of simulated environments in teacher education: Current and future possibilities. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2014, 37, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdig, R.E.; Baumgartner, E.; Hartshorne, R.; Kaplan-Rakowski, R.; Mouza, C. (Eds.) Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Waynesville, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dalinger, T.; Thomas, K.B.; Stansberry, S.; Xiu, Y. A mixed reality simulation offers strategic practice for pre-service teachers. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, S.E.; Ford, D.; Vaughn, M.; Fulchini-Scruggs, A. Using Mixed Reality Simulation and Roleplay to Develop Preservice Teachers’ Metacognitive Awareness. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2021, 29, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahnke, R.; Blömeke, S. Novice and expert teachers’ situation-specific skills regarding classroom management: What do they perceive, interpret and suggest? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 98, 103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, B.; Fairbanks, S.; Briesch, A.; Myers, D.; Sugai, G. Evidence-based practices in classroom management: Considerations for research to practice. Educ. Treat. Child. 2008, 31, 351–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, R.; Mainhard, T.; Van Tartwijk, J.; Veldman, I.; Verloop, N.; Wubbels, T. How pre-service teachers’ personality traits, self-efficacy, and discipline strategies contribute to the teacher–student relationship. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Xu, X. Virtual reality simulation-based learning of teaching with alternative perspectives taking. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2544–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.A.; Sethares, K.A. The use of guided reflection in simulation-based education with prelicensure nursing students: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Educ. 2022, 61, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzberger, D.; Philipp, A.; Kunter, M. Predicting teachers’ instructional behaviors: The interplay between self-efficacy and intrinsic needs. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Parker, P.D.; Marsh, H.W.; Kunter, M.; Schmeck, A.; Leutner, D. Self-efficacy in classroom management, classroom disturbances, and emotional exhaustion: A moderated mediation analysis of teacher candidates. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousay, T.A.; Trujillo, N.P. An examination of gender and situational interest in multimedia learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S.; Renninger, K.A. The four-phase model of interest development. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 41, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.E.; Hirsch, S.E.; McGraw, J.P.; Bradshaw, C.P. Preparing pre-service teachers to manage behavior problems in the classroom: The feasibility and acceptability of using a mixed-reality simulator. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2020, 35, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pas, E.T.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Bradshaw, C.P. Coaching teachers to detect, prevent, and respond to bullying using mixed reality simulation: An efficacy study in middle schools. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S. Revisiting the conceptualization, measurement, and generation of interest. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 46, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.F.; Luo, G.; Luo, S.; Liu, J.; Chan, K.K.; Chen, H.; Zhou, W.; Li, Z. Promoting pre-service teachers’ learning performance and perceptions of inclusive education: An augmented reality-based training through learning by design approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 148, 104661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martindale, S.; Hook, J.; Carter, R. A collective interdisciplinary agenda for immersive storytelling: Editorial analysis. Convergence 2025, 31, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R.; Watt, H.M.; Richardson, P.W. Teachers’ classroom management self-efficacy, perceived classroom management and teaching contexts from beginning until mid-career. Learn. Instr. 2020, 69, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustandi, C.; Ibrahim, N.; Muchtar, H. Virtual reality based on media simulation for preparing prospective teacher education students. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. (IJRTE) 2019, 8, 399–402. [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy, M.; Boerst, T. Designing Simulations to Learn About Pre-service Teachers’ Capabilities with Eliciting and Interpreting Student Thinking. In Research Advances in the Mathematical Education of Pre-service Elementary Teachers; Stylianides, G.J., Hino, K., Eds.; ICME-13 Monographs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collum, D.; Christensen, R.; Delicath, T.; Johnston, V. SimSchool: SPARCing New Grounds in Research on Simulated Classrooms. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 18 March 2019; Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/207723/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Cohen, J.; Wong, V.; Krishnamachari, A.; Berlin, R. Teacher coaching in a simulated environment. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2020, 42, 208–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schussler, D.; Frank, J.; Lee, T.K.; Mahfouz, J. Using Virtual Role-Play to Enhance Teacher Candidates’ Skills in Responding to Bullying. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2017, 25, 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, T.; Cooper, J.T.; Snider, K. A Comparison of Role-play v. Mixed-Reality Simulation on Pre-Service Teachers’ Behavior Management Practices. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2024, 40, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.; Vogt, M.; Miller, C. Effects of an Avatar-Based Simulation on Family Nurse Practitioner Students’ Self-Evaluated Suicide Prevention Knowledge and Confidence. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2024, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif Green, J.; Levine, R.S.; Oblath, R.; Corriveau, K.H.; Holt, M.K.; Albright, G. Pilot evaluation of preservice teacher training to improve preparedness and confidence to address student mental health. Evid.-Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 5, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Millman, M.; Bernstein, L.; Link, N.; Hoover, S.; Lever, N. Effectiveness of an online suicide prevention program for college faculty and students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soneson, E.; Howarth, E.; Weir, A.; Jones, P.B.; Fazel, M. Empowering School Staff to Support Pupil Mental Health Through a Brief, Interactive Web-Based Training Program: Mixed Methods Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e46764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Ferguson, S. Virtual Microteaching, Simulation Technology & Curricula: A Recipe for Improving Prospective Elementary Mathematics Teachers’ Confidence and Preparedness. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2021, 29, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Leslie, N.; Leslie, H.S. A Whole New World Since COVID-19: Integrating Mursion Virtual Reality Simulation in Teacher Preparation and Practice. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 11 April 2022; Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/220973/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Hopper, S. The heuristic sandbox: Developing teacher know-how through play in simSchool. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 2018, 29, 77–112. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/174847/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Hersted, L. Reflective role-playing in the development of dialogic skill. J. Transform. Educ. 2017, 15, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S.; Alinier, G.; Crawford, S.B.; Gordon, R.M.; Jenkins, D.; Wilson, C. Healthcare simulation standards of best practiceTM The debriefing process. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 58, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.M.; Bradshaw, C.P. Examining classroom influences on student perceptions of school climate: The role of classroom management and exclusionary discipline strategies. J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 51, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, C.S. “I want to be nice, but I have to be mean”: Exploring prospective teachers’ conceptions of caring and order. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1998, 14, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfolk Hoy, A.W.; Weinstein, C.S. Student and teacher perspectives on classroom management. In International Handbook of Classroom Management, Research, Practice and Contemporary Issues; CEvertson, M., Weinstein, C.S., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 181–223. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefele, U. Interest, learning, and motivation. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 26, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotgans, J.I.; Schmidt, H.G. Interest development: Arousing situational interest affects the growth trajectory of individual interest. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parong, J.; Mayer, R.E. Learning science in immersive virtual reality. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S. The impact of virtual reality on curiosity and other positive characteristics. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S. Student interest and achievement: Developmental issues raised by a case study. In Development of Achievement Motivation; Wigfield, A., Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipstein, R.L.; Renninger, K.A. Putting things into words: The development of 12-15 year-old students’ interest for writing. In Writing and Motivation; Hidi, S., Boscolo, P., Lipstein, R.L., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knogler, M.; Harackiewicz, J.M.; Gegenfurtner, A.; Lewalter, D. How situational is situational interest? Investigating the longitudinal structure of situational interest. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Aflecht, G.; Jaakkola, T.; Pongsakdi, N.; Hannula-Sormunen, M.; Brezovszky, B.; Lehtinen, E. The development of situational interest during a digital mathematics game. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Richter, E.; Kleickmann, T.; Wiepke, A.; Richter, D. Classroom complexity affects student teachers’ behavior in a VR classroom. Comput. Educ. 2021, 163, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Borre-Gude, S.; Mayer, R.E. Motivational and cognitive benefits of training in immersive virtual reality based on multiple assessments. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2019, 35, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Lee, S.; Hsu, Y. The Roles of Epistemic Curiosity and Situational Interest in Students’ Attitudinal Learning in Immersive Virtual Reality Environments. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2023, 61, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roure, C.; Lentillon-Kaestner, V.; Méard, J.; Pasco, D. Universality and uniqueness of students’ situational interest in physical education: Acomparative study. Psychol. Belg. 2019, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidi, S. An interest researcher’s perspective: The effects of extrinsic and intrinsic factors on motivation. In Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation; Sansone, C., Harackiewicz, J.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 309–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volet, S.; Jones, C.; Vauras, M. Attitude-, group-and activity-related differences in the quality of pre-service teacher students’ engagement in collaborative science learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2019, 73, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, C.A. Self-regulated learning and college students’ regulation of motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 90, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R. Classroom discipline and student responsibility: The students’ view. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Adesope, O. Exploring the effects of seductive details with the 4-phase model of interest. Learn. Motiv. 2016, 55, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S. Interest development, self-related information processing, and practice. Theory Pract. 2022, 61, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Smith, J.L.; Priniski, S.J. Interest matters: The importance of promoting interest in education. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2016, 3, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettinger, K.; Lazarides, R.; Rubach, C.; Schiefele, U. Teacher classroom management self-efficacy: Longitudinal relations to perceived teaching behaviors and student enjoyment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 103, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J. Self-efficacy and interest: Experimental studies of optimal incompetence. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapp, A. Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: Theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learn. Instr. 2002, 12, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenbrink-Garcia, L.; Patall, E.A.; Messersmith, E.E. Antecedents and consequences of situational interest. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 83, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, J.S.; O’Callaghan, C. Journeying towards the profession: Exploring liminal learning within mixed reality simulations. Action Teach. Educ. 2019, 41, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

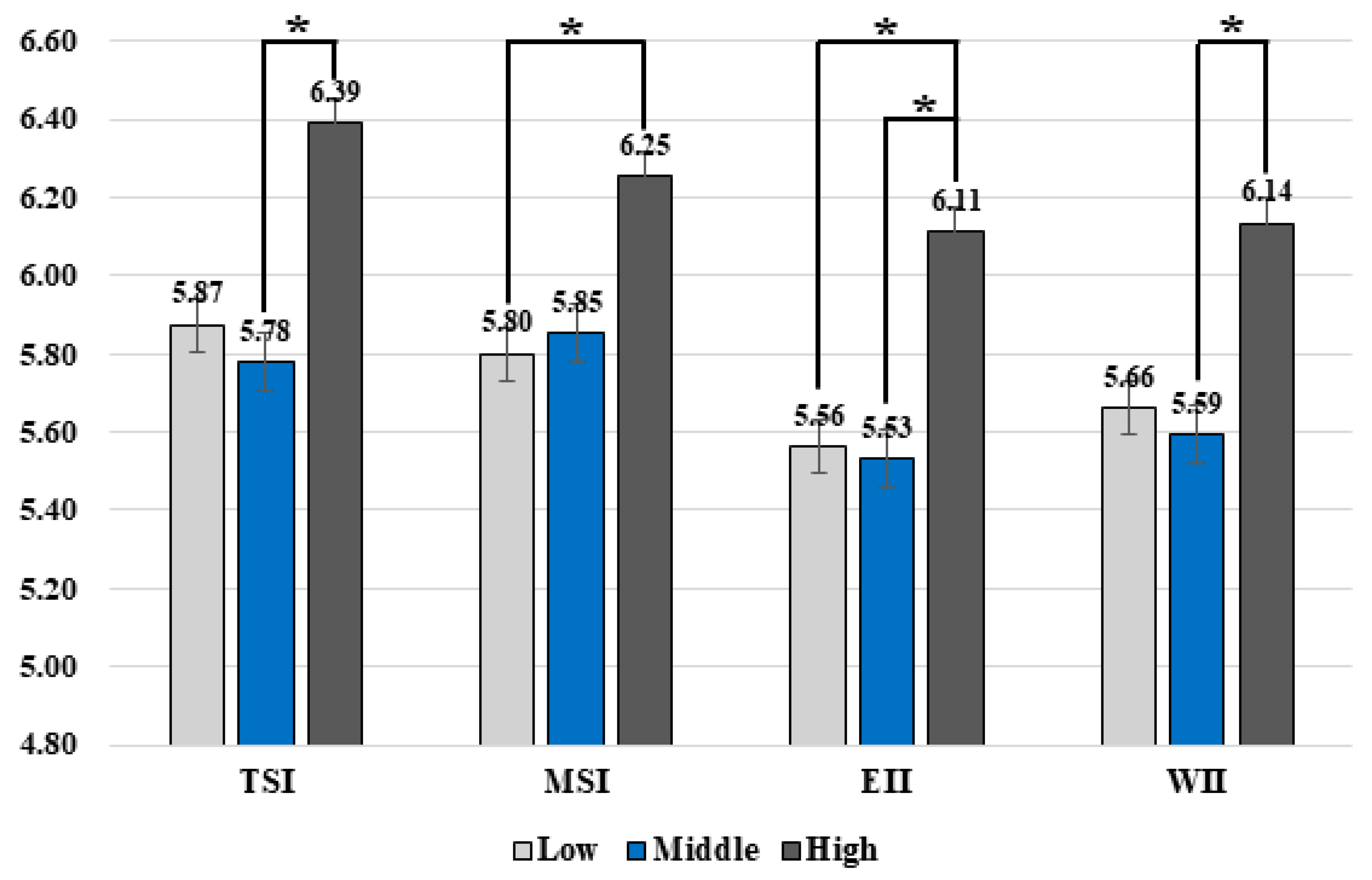

| Classroom Management Efficacy | Low (n = 19) | Middle (n = 19) | High (n = 19) | Total (N = 57) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest Development | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| TSI | 5.87 (0.75) | 5.78 (0.72) | 6.39 (0.74) | 6.01 (0.77) | |

| MSI | 5.80 (0.53) | 5.85 (0.48) | 6.25 (0.59) | 5.97 (0.56) | |

| EII | 5.56 (0.62) | 5.53 (0.67) | 6.11 (0.58) | 5.74 (0.67) | |

| WII | 5.66 (0.65) | 5.59 (0.34)1 | 6.14 (0.68) | 5.80 (0.62) | |

| Interest Development | (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I-J) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSI | Low | Middle High | 0.095 −0.516 | 0.924 0.107 |

| Middle | Low High | −0.095 −0.611 * | 0.924 0.046 | |

| High | Low Middle | 0.516 0.611 * | 0.107 0.046 | |

| MSI | Low | Middle High | −0.053 −0.453 * | 0.955 0.041 |

| Middle | Low High | 0.053 −0.400 | 0.955 0.080 | |

| High | Low Middle | 0.453 * 0.400 | 0.041 0.080 | |

| EII | Low | Middle High | 0.030 −0.579 * | 0.989 0.022 |

| Middle | Low High | 0.549 * 0.579 * | 0.031 0.022 | |

| High | Low Middle | 0.549 * 0.579 * | 0.031 0.022 | |

| WII | Low | Middle High | 0.069 −0.472 | 0.935 0.051 |

| Middle | Low High | 0.069 −0.541 * | 0.935 0.021 | |

| High | Low Middle | 0.472 * 0.541 * | 0.051 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ki, S.; Park, S.; Ryu, J. The Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Development in Guided Role-Playing Simulations for Sustainable Pre-Service Teacher Training. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146257

Ki S, Park S, Ryu J. The Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Development in Guided Role-Playing Simulations for Sustainable Pre-Service Teacher Training. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146257

Chicago/Turabian StyleKi, Suhyun, Sanghoon Park, and Jeeheon Ryu. 2025. "The Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Development in Guided Role-Playing Simulations for Sustainable Pre-Service Teacher Training" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146257

APA StyleKi, S., Park, S., & Ryu, J. (2025). The Effects of Classroom Management Efficacy on Interest Development in Guided Role-Playing Simulations for Sustainable Pre-Service Teacher Training. Sustainability, 17(14), 6257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146257