1. Introduction

The fortifications of the Kraków Fortress, built in the 19th century, are among the most important military monuments in Poland. Over the years, many of these facilities have deteriorated, creating a need for their revitalization. This process is complex, requiring the cooperation of various entities, including public administration, the private sector, and the local community. It is also a long-term and complex process, in which many stakeholders are involved, and various sources of financing are used. Public–private cooperation can be an effective form of implementing such projects, contributing to the protection of cultural heritage and the development of urban space. This is also facilitated by the amendment to the Revitalization Act, adopted on 29 July 2024, introducing changes regarding Special Revitalization Zones (SRZ). So, what legal, financial, social, and environmental consequences did this new amendment bring in the context of the revitalization of historic military facilities, using the example of the Kraków Fortress? This question is the starting point for analyzing the impact of legislative changes on revitalization processes.

2. Comprehensive Revitalization of the Kraków Fortress Facilities

2.1. Comparative Approach and International Context

Although the revitalization of the Kraków Fortress is a process strongly rooted in the local legal, social, and historical context, it is also worth relating it to international experiences in the field of protection and adaptation of military heritage. At the European level, there are many examples of successful revitalization processes of former fortifications, such as the Citadel in Antwerp (Belgium), the Vauban Fortresses in Neuf-Brisach (France), or the Fortifications in St. Petersburg (Russia). The literature emphasizes the importance of public–private partnerships and the integration of revitalization activities with urban policy, which is also reflected in the actions taken in Kraków.

Studies such as Adaptive Reuse of Military Heritage in Europe (Berti, 2021) [

1] and analyses of projects financed by EU programs such as Interreg or URBACT indicate that effective revitalization of defensive facilities requires:

transforming their functions from military to socio-cultural;

ensuring sustainable sources of financing;

a participatory approach involving the local community;

a strong educational and promotional component.

In comparison to these international projects, the revitalization of the Kraków Fortress shows both common features (e.g., adaptation to cultural functions, use of EU funds) [

2,

3,

4], as well as certain differences, such as the exceptionally dispersed nature of the fort complex in the urban space and close connection with the urban system of spatial planning and revitalization zones (SSR) [

5].

In light of international experiences and the revitalization of the Kraków Fortress, it is also worth noting the growing importance of sustainable tourism (ST) in the protection of cultural heritage (CH). Studies on iconic Chinese heritage sites such as the Great Wall and the Forbidden City show that ST practices significantly contribute to the preservation of CH by promoting positive visitor behavior, raising awareness, and ensuring long-term protection. These results emphasize that the integration of educational efforts, community participation, and sustainable development strategies emphasized in both Europe and Asia is essential to protect military and cultural heritage for future generations [

6].

2.2. Key Aspects of the Revitalization of the Kraków Fortress

In the context of the fortifications of the Kraków Fortress, we can consider various aspects of revitalization, such as:

Extension of the SRZ boundaries—which envisages the extension of the Special Revitalization Zones to include a larger part of the fortifications and adjacent areas, which aims to protect and revitalize these areas better. In October 2022, the Kraków City Council adopted Resolution No. XCVII/2644/22, designating a degraded area and a revitalization area. This resolution is part of the long-term program of the City of Kraków, covering the revitalization of three revitalization areas: “old” Nowa Huta, Kazimierz-Stradom, and Grzegórzki-Wesoła. These areas were indicated on the basis of a socio-economic diagnosis, which identified the occurrence of negative phenomena, such as social, economic, environmental, and technical problems [

6].

Financial support—which anticipates an increase in financial resources for the revitalization of fortifications, including the possibility of obtaining funds from the European Union and other external sources, and support for private investors involved in revitalization works. In the process of revitalization of the Kraków Fortress facilities, diverse sources of financing play a key role [

7,

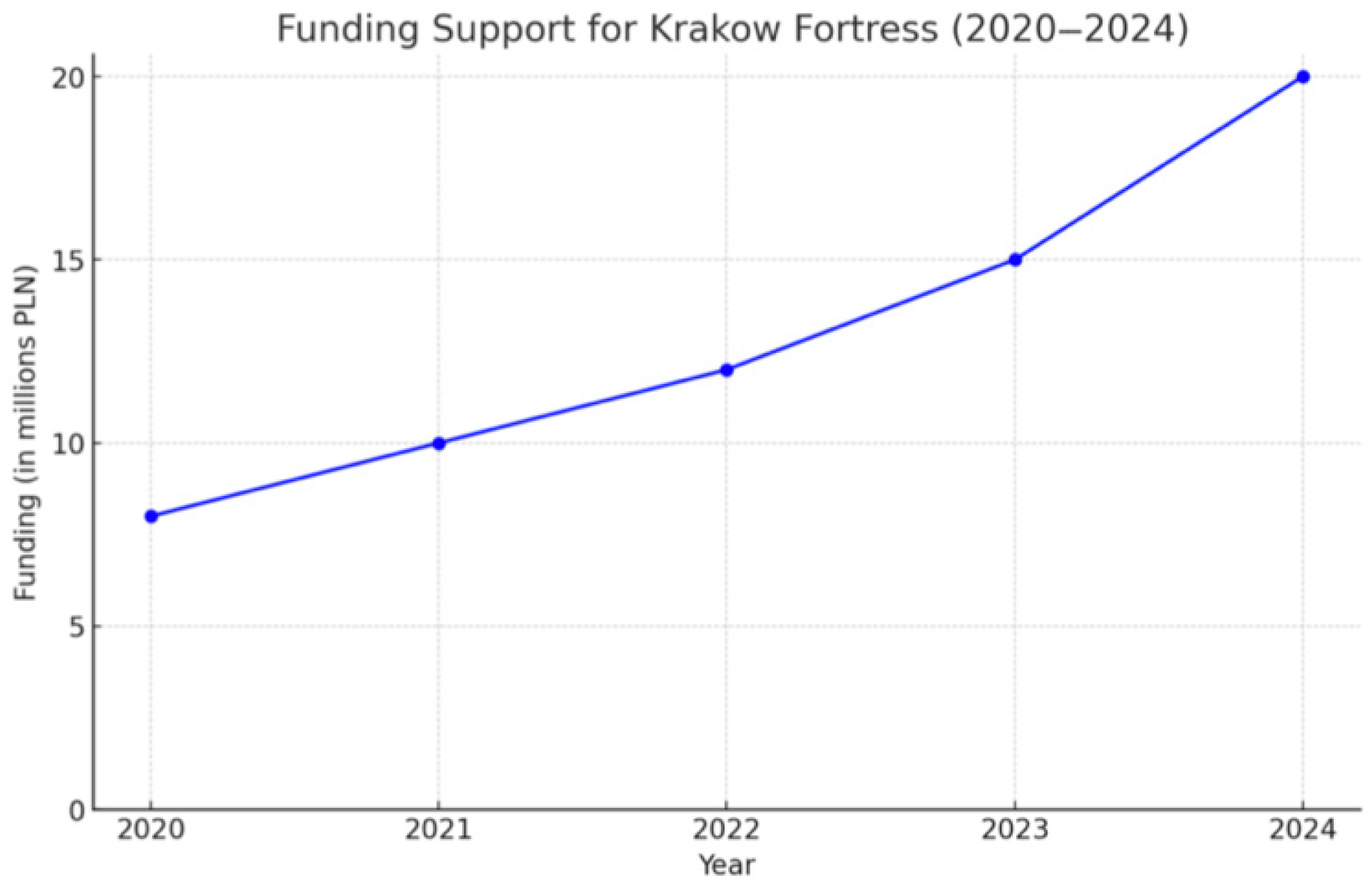

8]. In the years 2020–2024, numerous renovation and adaptation works were carried out in various forts that are part of the Kraków Fortress (

Figure 1). The issue of the value of adaptive reuse of fortification monuments has been widely discussed in the literature [

9]. The works included Fort 49 “Krzesławice”, Fort 51 “Rajsko”, Fort 52 “Borek”, and many others. These activities were aimed not only at renovating historic structures, but also at adapting them to new functions, such as cultural centers, museums, or recreational spaces.

Over the years 2020–2024, funds in the amount of over PLN 50 million were acquired [

10,

11]. The analyzed data show growing financial involvement in the revitalization of the fortress facilities, which reflects increased expenditures from various sources, such as EU funds, the budget of the Municipality of Kraków, and the Social Committee for the Renovation of Kraków Monuments (SKOZK).

Protection of cultural heritage—places great emphasis on the protection of the cultural and historical heritage of the Kraków Fortress. It introduces new regulations regarding the conservation and renovation of monuments, as well as the rules of conduct during construction and renovation works. Guidelines for the protection of cultural heritage apply to the conservation and revitalization of the Kraków Fortress. Documents such as the “Guidelines for the Management of the Historic Centre of Kraków” for the years 2023–2035, developed by the Department of Culture and National Heritage of the City of Kraków, contain recommendations aimed at preserving and developing the city’s cultural heritage. These guidelines are consistent with the strategic goals of Kraków, including the protection of material heritage and improving the quality of life of residents through the integration of local communities and the development of tourism [

12,

13].

Sustainable development—introduces the principles of sustainable development, which are to ensure harmonious cooperation between environmental protection, the interests of local communities, and the development of tourism and recreation in the area of the Kraków Fortress.

Social participation—strengthens the role of local communities in the revitalization process. The amendment provides greater involvement of residents and non-governmental organizations in planning and implementing revitalization projects.

Promotion and education—increases promotional and educational activities aimed at raising awareness of the historical and cultural value of the Kraków Fortress, as well as the importance of revitalization for the local community.

In the process of revitalizing the Kraków Fortress, a key role is played by numerous stakeholders: the city government provides financing and coordination, cultural institutions are responsible for new social functions, conservators protect the historical value, and public–private partnership enables obtaining additional funds and effective implementation of projects. Community involvement through consultations, NGO participation, and educational programs promotes the acceptance of activities and the durability of effects. Participatory planning increases transparency, supports the integration of residents, and gives the facilities new, locally rooted functions.

2.3. The Importance of Revitalizing the Kraków Fortress

The revitalization of Kraków forts, such as Fort 52 “Borek”, Fort 52a “Jugowice”, Fort 2 “Kościuszko”, Fort 49 “Krzesławice”, and Fort 31 “Św. Benedict”, is of particular importance both at the local level and in a broader, nationwide, or even European, context. The presented examples show how to effectively combine the protection of cultural heritage with a modern approach to sustainable development and the social needs of modern cities. Above all, these activities support the preservation of local identity and historical memory. Forts are no longer perceived as relics of the past, but as active social spaces, i.e., places for meetings, education, recreation, and culture. In this way, they regain their significance in the lives of residents, and at the same time, contribute to building a community and counteracting the phenomenon of social exclusion. Social integration around the common heritage is possible thanks to the creation of open public spaces that are also accessible to people with disabilities. From an ecological point of view, the revitalization of forts is an example of good practices in the field of adaptation of existing infrastructure. Instead of building from scratch, which would involve high resource consumption and carbon dioxide emissions, the focus was on modernizing existing facilities. Energy-saving solutions were used, such as LED systems, heat pumps, and photovoltaics. In addition, natural and local building materials and low-emission technologies were used. In many cases, biodiversity and rainwater retention were also taken care of, which shows that revitalization can be a tool for real environmental protection. It is also worth paying attention to the educational and culture-forming aspect of these investments. The spaces of former forts have been adapted for exhibition, museum, and workshop purposes. Places have been created where children, young people, and adults can learn about history, participate in cultural events, and develop their interests. The example of Fort 52a, where the Museum and Centre of the Scout Movement operates, or Fort 31, which is to have an educational function, shows that heritage can be a living tool for teaching values, history, and civic responsibility. The economic context is also important. Thanks to their cultural and educational functions, revitalized facilities attract visitors, generate income, create jobs, and revitalize the surrounding areas. The increase in tourist and social attractiveness has a positive impact on the local economy, supporting the development of services, gastronomy, and crafts. This approach, known in urban planning as regeneration through culture, is increasingly used in European cities as an effective method of counteracting spatial degradation. The cases of revitalization of Kraków’s forts are consistent with the assumptions of the urban policy promoted by documents such as Agenda 2030, the European Green Deal, or the New Leipzig Charter. They show that caring for monuments is not only an obligation resulting from regulations but can be a conscious choice that connects the past with the future. These projects can be a model for other cities in Poland and abroad to follow, where similar facilities are awaiting their “second life”. In this way, cultural heritage becomes not only a subject of protection but a real tool for shaping modern, sustainable, and inclusive urban spaces.

3. Detailed Analysis of Revitalization Works

This study is based on an interdisciplinary theoretical framework combining the concepts of cultural heritage, sustainable development, and urban revitalization. Based on the UNESCO definition of heritage as a public good and the principles of sustainable development set out in the UN Agenda 2030, the analysis examines how revitalized fortifications can serve social, environmental, and economic purposes. The revitalization of the Kraków Fortress is treated as a case of adaptive reuse in line with integrated urban development strategies. The methodology is based on a qualitative case study analysis of five forts. They were selected because they have extensive documentation and can represent different stages of revitalization, functional assumptions, and financing models. Data sources include official reports from municipal and national institutions (e.g., SKOZK, Kraków City Office), project documentation, EU funding records, and publicly available data on their locations. In addition, visual materials and technical specifications were used to assess ecological improvements and accessibility. This approach ensures transparency, comparability, and repeatability in similar urban heritage studies.

3.1. Fort 52 “Borek”

In 2022, the revitalization of the “Borek” [

14,

15] fort was completed (

Figure 2), which currently houses the “Kliny” Culture Club, the Podgórze Culture Center, and the Culture Center-Library of Polish Songs. It is an excellent example of adapting a historic facility while taking into account the principles of sustainable development. The revitalization process included not only restoring the former glory of the facility but also adapting it to contemporary social, cultural, and ecological needs. The total cost of the investment amounted to over PLN 24 million, of which almost PLN 10 million came from external sources, including EU funds and the Regional Operational Program of the Małopolska Province.

The scope of renovation works in the context of sustainable development consisted, among others, of preserving cultural heritage, including the renovation of the fort’s historic walls, while respecting the original building materials and construction techniques, as well as the reconstruction of architectural details and historic elements by historical documentation; completing missing parts of the building in accordance with conservation principles, in order to preserve the authenticity of the facility as much as possible; adaptation to contemporary needs, consisting of transforming the fort into a modern cultural center for the local community (adaptation works included providing multifunctional spaces for the organization of events, workshops, social meetings, and other cultural activities), and; creating common spaces, such as cafes, rest areas, and green areas, which facilitate the integration of the local community. The renovation of green areas around the facility was not omitted either. These works consisted of renovating the green areas around the fort, including planting new trees, shrubs, and plants to improve the air quality and microclimate. Creating walking and recreational paths for residents and visitors. The culmination of any revitalization of a historical facility should be its restoration, not only to perfect technical condition but also to revitalize the place in the social sphere. This is helped by education and promotion of the fort in the form of organizing workshops, exhibitions, and educational events promoting the idea of protecting cultural heritage. This is helped by the creation of an exhibition space, where the history of the fort and its significance in the history of Kraków are presented.

The effects of revitalization in the context of sustainable development can be summarized as follows:

The revitalized fort “Borek” has become a friendly space for residents, contributing to social integration;

The revitalization process has minimized the negative impact on the environment, owing to the use of ecological technologies;

The facility has not only retained its historical significance, but also gained a new function, responding to the needs of modern society;

A sustainable model of space management has been created, combining the protection of cultural heritage with care for the environment and the needs of the local community.

3.2. Fort 52a “Jugowice”

Fort 52a “Jugowice” (

Figure 3) in Kraków was officially opened after revitalization on 29 September 2023 [

16,

17,

18]. Works on transforming the ruined fort into the Museum and Center of the Scout Movement lasted several years and were supported by the National Fund for the Revalorization of Kraków Monuments. The total cost of the investment amounted to approximately PLN 31 million. Their distribution was as follows: funds from the Municipality of Kraków amounted to PLN 22.4 million, which is 73% of the costs, funds obtained from EU grants amounted to PLN 6.9 million, which is 23% of the total amount, while funds from the Social Committee for the Renovation of Kraków Monuments amounted to 4%, i.e., PLN 1.3 million.

The scope of the renovation works at Fort 52a Jugowice consisted primarily of restoring the historical architecture of the building. The brick and concrete walls were cleaned, reinforced, and preserved in accordance with conservation requirements. Architectural details such as vaults, cornices, and portals were renovated using traditional construction techniques, and the original appearance of the building was recreated while maintaining the authenticity of the materials. In addition, care was taken to restore the functionality of the interiors in the area of adapting the rooms to serve exhibition, educational, and conference functions. In accordance with the adaptation assumptions, modern air conditioning and ventilation systems were used, which are energy-efficient and neutral for the environment, and care was also taken to install sanitary and electrical infrastructure that meets modern ecological standards. The recultivation of the fort’s surroundings included the development of green areas around the fort, taking into account the natural landscape; planting native plant species supported the biodiversity of the local ecosystem; tidying up the existing moat and other defensive elements so that they would become an integral part of the recreational area; and adaptation to new functions, i.e., the creation of the Scout Movement Museum and Centre—a space promoting historical and cultural education—included the use of flexible internal solutions that allowed the space to be adapted to various activities (workshops, exhibitions, conferences).

In addition, the new extension harmoniously combines modern architecture with the historic character of the fort. It was designed with functionality and aesthetics in mind, taking into account the needs of the museum and education. The new facility includes spacious exhibition and conference halls and educational rooms, which are used both for the presentation of exhibits and the organization of workshops or meetings.

The facade of the new part refers to the original architecture of the fort, using materials and stylistic details characteristic of the original structure. Thanks to this, the new development harmonizes with the historic building, creating a coherent total. The interiors of the extension are modern, but retain an industrial character, which emphasizes the historical context of the place.

To sum up the aspects of sustainable development in the revitalization of Fort No. 52a, one can notice the care taken to protect cultural heritage, where the priority was to preserve the authenticity of the historic building, which allows the transfer of its historical value to future generations. It can be stated that the revitalization of the building is in line with the strategy of protecting the cultural heritage of Kraków, supporting local social identity, and tradition. It is also worth emphasizing that most of the fort buildings have extensive green areas around them, which is a result of their former function. Therefore, the use of these places around the fort promotes natural solutions that limit the effects of urbanization. The recultivation of greenery promotes the absorption of carbon dioxide, supporting the fight against local air pollution.

The effects of social integration and education are implemented in the facility in the form of meetings of the local community, which facilitates the development of social bonds and the implementation of educational programs in the Museum and the Scout Movement Center supporting the promotion of values based on the principles contained in the Scout Law and Promise. These principles are universal and aim to shape character, personal development, and an attitude of responsibility towards others and the world, among others, promoting the idea of sustainable development and ecology. When planning the revitalization of the facility, long-term use was not forgotten. The project provides for the financial self-sufficiency of the facility through the organization of cultural, educational, and recreational events, and the management model assumes minimizing operating costs through the efficient use of the facility’s resources.

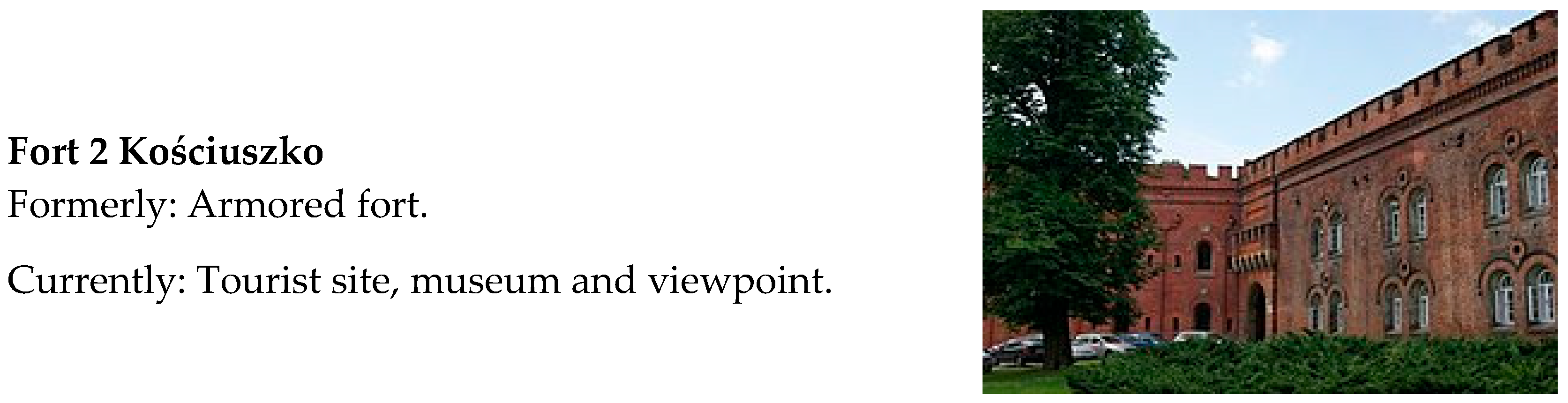

3.3. Fort 2 “Kościuszko”

The revitalization of Fort 2 “Kościuszko” in Kraków was completed in October 2024, after approximately 10 years of work (

Figure 4). The ceremonial opening of the renovated facility took place on 13 October 2024. These activities are an example of a comprehensive renovation project that takes into account the principles of sustainable development, i.e., care for the environment, social needs, and economic aspects. Fort “Kościuszko” [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], one of the most important and recognizable objects of the Kraków Fortress, gained new life thanks to its thoughtful adaptation for cultural, recreational, and educational purposes [

25]. The revitalization of Fort 2 “Kościuszko” in Kraków was an undertaking financed from various sources. The total cost of the investment amounted to approximately PLN 35 million. The main sources of financing included the Social Committee for the Renovation of Kraków Monuments (SKOZK), which provided co-financing in the amount of PLN 4.5 million from the National Fund for the Revalorization of Kraków Monuments. In addition, European Union funds were obtained from the Regional Operational Program of the Małopolska Province, PLN 13.5 million. The participant was the Budget of the Municipality of Kraków in the amount of about 17 million PLN; this part was financed from the municipality’s own funds. Thanks to these funds, it was possible to carry out revitalization works, including, among others, the discovery and protection of the relics of the bastions, the conservation of the historic walls, and the development of the area around the fort for recreational and leisure purposes.

The renovation works undertaken at Fort Kościuszko included activities aimed at reconstructing the historical structure of the building. Among other things, the original appearance of bastions I–III, which were destroyed during World War II and in the post-war years, was restored. Authentic building materials, such as stone and brick, were used for the works, consistent with the historical character of the building. In accordance with the conservation recommendations, care was taken to preserve architectural details, such as gun slots, casemates, and retaining walls. Relics of the fortifications, such as bastion walls, caponiers, artillery hangars, and posterns, were excavated, secured, and subjected to conservation. The works also included the construction of a glass roof over the courtyard of Bastion V. The roof consists of several dozen triangular panes with a built-in heating system. This structure does not distort the silhouette of the fort and provides additional space for meetings, events, and exhibitions. The interior of the bastion was cleaned of secondary cement plasters, which allowed the original brick walls to be exposed, in line with the original intention of the Austrian builders. As in the case of the previously described revitalizations, care was taken to develop the available areas around the fort. Park lighting was introduced, and the old walls were illuminated. Green recreational spaces were created, which are in line with the city’s strategy for the protection of biodiversity [

26]. New plantings typical of the local environment were made, which helps maintain ecological balance. In addition, the fortress moat was partially restored, which improved the aesthetic and hydrological values of the area. Adaptation for social and cultural purposes included the creation of exhibition spaces for cultural and educational activities, open to residents and tourists. In one of the bastions, a museum space was organized devoted to the history of the fort and the objects of the Kraków Fortress. The facility became a place for organizing artistic events, workshops, and historical education. Materials used in the renovation work were largely recycled or obtained locally, which reduced CO

2 emissions during transport.

The protection of cultural heritage in a socio-economic context takes on a new meaning, fulfilling functions that facilitate the integration of the local community and stimulate interest in the history and identity of a given region. The facility attracts tourists, and as a result, generates income for local businesses and supports the development of services related to culture and recreation. Long-term value is the use of pro-ecological solutions and adaptation to modern standards. The fort will maintain its functionality for decades to come. The investment combines the protection of monuments with care for the environment and the needs of residents, which makes it a model to follow in other renovation projects in Poland and Europe.

3.4. Fort 49 “Krzesławice”

Fort 49 “Krzesławice” in Kraków, part of the Kraków Fortress, has been the seat of the Fort 49 “Krzesławice” Youth Cultural Center since the mid-1990s (

Figure 5). Since then, revitalization works have been carried out there, aimed at restoring the facility to use and preserving its historical value [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Financing for these works comes mainly from the budget of the Municipality of Kraków. Additionally, the revitalization of the fort is supported by the National Fund for the Revalorization of Kraków Monuments, managed by the Social Committee for the Renovation of Kraków Monuments (SKOZK). In the SKOZK report from 2021, the fort was listed as a place of martyrdom from the period of World War II, which emphasizes its historical significance and the need for further conservation work. As part of the revitalization works carried out in recent years, among others, the partial reconstruction of the fortress moats with the bay of the front caponier and the development of the area around the moat and emergency shelters were carried out. In addition, the entrance doors to the main building were replaced, and the art room was renovated.

Thanks to these funds, Fort 49 “Krzesławice” has become a model example of adapting a former fortification to modern public utility purposes, serving as an educational and cultural facility for the local community.

3.5. Fort 31 “Św. Benedyk”

The revitalization of Fort 31 “St. Benedict” [

31] in Kraków is being carried out in stages (

Figure 6), and the total cost of the investment is estimated at approximately PLN 21.5 million. Within this amount, approximately PLN 3.7 million has been earmarked for conservation work on the facade and interior renovation. Additionally, PLN 935 thousand has been allocated for the development of design documentation, and approximately PLN 2.25 million for the performance of conservation work on the facade and interior renovation. The planned completion of the fort revitalization is the end of 2026.

Currently, work is underway to adapt the fort for educational purposes, which will be carried out by the Museum of Engineering and Technology. Further adaptation work is planned, including installation, flooring and interior finishing.

Contemporary revitalization activities carried out in the area of the former Kraków Fortress constitute one of the most comprehensive and inspiring examples of sustainable management of cultural heritage in urban space. The described cases of adaptation of forts—52 “Borek”, 52a “Jugowice”, 2 “Kościuszko”, 49 “Krzesławice”, and 31 “Św. Benedict”—is not only an expression of concern for the historical architectural substance, but also proof of the effective combination of monument protection with the needs of contemporary residents and ecological priorities.

In a broader context, it should be emphasized that all these investments are part of a long-term and strategic vision of the development of the former military infrastructure of the Kraków Fortress, the significance of which today goes far beyond its original defensive function. Built by the Austrians in the 19th century, the Fortress included dozens of forts located around the city, which eventually ceased to serve military functions and deteriorated. The contemporary revitalization of these facilities is a response to the need to reclaim historical spaces and incorporate them into urban life, in accordance with the idea of sustainable development and diversified, polycentric spatial planning. Each of the forts covered by the revitalization was given a unique, yet coherent function within the framework of urban policy, starting from local cultural centers, through museums, to educational places. Fort 52 “Borek” was transformed into a cultural center and the seat of a library, Fort 52a “Jugowice” became the seat of the Museum and Center of the Scout Movement, Fort 2 “Kościuszko” currently serves as a museum and tourist center, Fort 49 “Krzesławice” operates as a Youth Culture Center, and Fort 31 “St. Benedict” is to serve as an educational center under the auspices of the Museum of Engineering and Technology. Thus, each of these facilities responds to the local needs of the community, but all together create a dense network of places of cultural, educational, and social activity in various districts of Kraków. In parallel with the adaptation to new functions, advanced conservation activities were carried out, which allowed the preservation of original architectural features and, in many cases, the reconstruction of lost historical elements as well. In particular, attention was paid to the use of materials and techniques consistent with the original ones, which increases the authenticity of the facilities. In the case of Fort 2 “Kościuszko” or Fort 52a “Jugowice”, these activities were wide-ranging and included, among others, the reconstruction of destroyed bastions, casemates, and historical walls. The revitalization of the forts was also an opportunity to implement modern ecological solutions. In all cases, care was taken to install energy-saving installations, LED lighting, modern heating systems, and heat pumps were often used, as well as infrastructure for rainwater retention. Importantly, extensive green areas around the facilities were revitalized, plants supporting local biodiversity were planted, and, in some places, such as around Fort “Kościuszko”, even historical moats were renovated. In this way, former defensive spaces were transformed into publicly accessible recreational areas, integrating them with urban greenery. Another aspect that unites the revitalization of the forts discussed is the strong setting of these activities in a social and educational context. Workshops, cultural events, conferences, and activities promoting knowledge about the history of the region and the importance of cultural heritage are organized in the spaces of the revitalized facilities. Fort Jugowice holds a special place here, educating young generations in the spirit of social responsibility, patriotism, and respect for the environment, thanks to scouting activities. Fort “Krzesławice” also maintains an important function as a place of remembrance and historical reflection. It is worth noting that the revitalization of the facilities of the Kraków Fortress also has an economic dimension—by attracting tourists, organizing events, and creating new jobs, fortress investments support local economic development. In many cases, financing models have been developed that assume long-term self-sufficiency of the facilities, which reduces the burden on the city budget and promotes effective management of public space. In addition, revitalization activities undertaken within the former Kraków Fortress should be treated as a model example of a modern, integrated approach to managing historical space in the city. By combining the protection of cultural heritage, care for the natural environment, and real social needs, Kraków creates a system of dispersed but interconnected centers of urban life, which constitute an important part of the identity and functioning of the modern metropolis.

The results of the revitalization of the forts in Kraków show an effective combination of cultural heritage protection with the needs of contemporary residents and care for the environment. The facilities have gained new social, educational, and recreational functions, supporting the integration of local communities. Ecological technical solutions have been introduced, and greenery has been taken care of. Long-term management plans assume financial self-sufficiency of the facilities, low operating costs, and their permanent inclusion in the urban fabric. Thanks to this, the projects have real potential to permanently support the sustainable development of the city on many levels.

4. Sources of Financing for the Revitalization and Renovation of the Kraków Fortress Facilities

Revitalization and renovation of the forts of the Kraków Fortress is a complex process requiring significant financial outlays, which is based on diverse sources of financing. Due to their historical, cultural, and social significance, these projects involve both public and private funds. The main sources of financing for activities related to the renovation of the forts of the Kraków Fortress, such as public funds from the state budget, include: the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, which finances projects related to the protection of monuments, including renovation and conservation works of forts; the Monument Protection Fund, which supports projects related to the preservation and renovation of objects entered in the Register of Monuments, and; local government funds, which are based on financing from the resources of the Municipality of Kraków and from the resources of the Małopolska Province, which allocate funds for the revitalization of forts, especially those performing socio-cultural functions, as well as local programs, such as “Revalorization of Kraków Monuments”, which support works on the area of the Kraków Fortress. With such a large scale of revitalization of facilities, European funds are indispensable in the form of the Regional Operational Program of the Małopolska Province and the Infrastructure and Environment programs, which finance activities related to the protection of cultural heritage. This financing is supplemented by funds from the Public–Private Partnership (PPP), as an example of which is the previously mentioned Fort 51 “Rajsko”, as well as international foundations and grants such as the Princes Czartoryski Foundation or the Polish Cultural Heritage Foundation, which support the protection of monuments, and international organizations, such as UNESCO, which support projects of great cultural importance.

4.1. Criteria for Selecting Forts

The selection of forts for analysis was based on various criteria, such as: current revitalization status (completed, ongoing, planned), social functions after revitalization, sources of financing, and availability of public information about the activities carried out. Both facilities where the revitalization process has already been completed (e.g., Fort No. 52 “Borek”, Fort No. 52a “Jugowice”, Fort No. 2 “Kościuszko”) and those where work is still being carried out or planned (e.g., Fort No. 31 “St. Benedict”) were included in the analysis. The case of a fort transferred on lease, where the revitalization is carried out by a private entity (Fort No. 51 “Rajsko”), was also included. Not all revitalized forts in Kraków were included. The selection is a representative sample of facilities with different levels of work advancement, different purposes, and different financing models. The aim of this approach was to show a wide range of revitalization activities carried out in the city, without aiming at a full inventory of fortress resources.

Additionally, as part of the revitalization of the forts of the Kraków Fortress, mechanisms were implemented to ensure inclusiveness and equal access to the revitalized spaces. Key activities included:

Creation of publicly accessible and multifunctional spaces (e.g., workshop and exhibition rooms, local integration places);

Designing spaces friendly to all social groups, including children, youth, and seniors;

Organization of cultural, educational, and recreational events that promote active participation of various groups of residents.

In addition, public participation in the revitalization process was implemented mainly through:

Public consultations and information meetings with residents, organized by city institutions and facility operators (e.g., Podgórze Cultural Centre);

Involvement of local communities (e.g., scouts, cultural organizations, local community) in creating functional programs for forts;

Conducting social education aimed at promoting cultural heritage and the principles of sustainable development.

From the available information, it does not appear that there were any serious social conflicts during the consultations. The revitalization process was rather perceived as a positive action, strengthening local identity and opening up new opportunities for socio-cultural development.

Table 1 is a list of selected forts of the Kraków Fortress along with information on their revitalization and sources of financing:

A comparative analysis of the revitalization process of the Kraków Fortress forts with similar projects in European cities such as Antwerp (Belgium) or Neuf-Brisach (France) allows us to see key differences and similarities in the approach to financing and developing fortress spaces. In the case of Antwerp, the revitalization of the fortifications was largely based on an integrated approach of the city, using EU funds in combination with private investments and long-term urban planning. Neuf-Brisach, on the other hand, as a UNESCO site, benefits from strong international support and French funds earmarked for cultural heritage. In Kraków, despite the multi-source financing model (including EU funds, local government funds, and PPP), there is often a lack of cost standardization; the use of uniform units (e.g., revitalization cost per m2) would allow for a better comparison of the effectiveness of individual projects. Such data is unfortunately difficult to obtain, and, considering the long-term nature of the revitalization processes of fortress facilities, including not only frequent implementation delays, but also shifts and limitations of financial resources, changing design assumptions and modifications to the concept of the scope of renovation, as well as dynamically changing prices of labor and construction materials, their comparison becomes practically impossible. In the European context, Kraków, on the other hand, stands out for its intense social involvement in the revitalization process, which favors local integration and the durability of the socio-cultural functions of facilities.

The revitalization of the Kraków Fortress facilities has brought tangible socio-economic and environmental effects (

Table 2). The number of visitors has increased from 20,000 (2019) to over 75,000 per year (2024), which generates revenue from tourism and local services. Thanks to the new functions of the forts, approx. 120 jobs have been created in the culture and services sector. In terms of ecology, these projects have contributed to reducing energy consumption by over 30% compared to the state before modernization.

4.2. International Context of Revitalization of the Kraków Fortress

The revitalization and renovation of the Kraków Fortress forts is a complex and long-term process that requires significant financial outlays and the cooperation of many stakeholders. Transforming former military facilities into spaces of culture, education, and recreation is part of the broader trend of European strategies for the regeneration of military heritage [

32]. Such interventions not only restore the functional value of historical objects but also become a carrier of local identity and an instrument of social activation [

33]. The literature on the subject emphasizes that effective revitalization of military heritage is based on the use of diversified sources of financing, as well as integration with city and regional policies [

34,

35,

36]. This approach is in line with the UNESCO and ICOMOS guidelines on the protection of cultural heritage, which point to the need for social participation, sustainable use, and combining the conservation and development functions [

37].

In the theoretical approach, this process can be analyzed through the prism of several key concepts:

Integrated approach to revitalization (Integrated Urban Regeneration)—According to the approach presented by Couch, Fraser, and Percy [

38], revitalization should be an integrated process, combining social, economic, and spatial aspects. The participation of stakeholders and the diversification of financing sources, including public, EU, and private funds, are of key importance here [

39].

Theory of cultural heritage value—As indicated by Mason and Throsby [

40,

41], cultural heritage sites have both economic and intangible value (historical, symbolic, social). This value can be capitalized through revitalization activities that justify the involvement of public budget resources and EU funds.

Public–private partnership (PPP)—The PPP model, widely discussed by Hodge and Greve [

39], is an effective form of implementing infrastructure investments, also in the cultural sector. The revitalization of the Rajsko Fort in the PPP formula confirms the practical application of this theory. PPP allows for the transfer of risks and costs, as well as the introduction of innovative models of facility management.

Heritage Policy Theory

International studies, e.g., by Logan [

42] or Smith [

43], emphasize that heritage protection policies shape the choice of financing mechanisms. These mechanisms include, among others, structural funds, grants from international organizations (e.g., UNESCO), and local programs for the protection of monuments.

Mixed Funding Model—As noted by Licciardi and Amirtahmasebi [

2], effective heritage revitalization requires a financing model based on a combination of local, central, and international funds, which ensures flexibility and resistance to changes in the availability of funds.

In the case of the Kraków Fortress, a mixed model was used, including both public funds (state and local government), EU funds, and a private component in the form of public-private partnerships and civic initiatives, and foundations. Such differentiation is consistent with the hybrid approaches recommended in the literature [

35], which increase the resilience of revitalization projects to changing economic and political conditions. This study adopts a case study approach, analyzing specific examples of forts of the Kraków Fortress and their revitalization status and sources of financing. It is worth noting that while some interventions—such as Fort No. 52 “Borek” or Fort No. 2 “Kościuszko”—can be considered model due to their full functional integration with the urban structure, others—such as Fort No. 51 “Rajsko”—are still in the experimental phase and require further evaluation. In the international context, similar processes can be observed, for example, in Germany (the case of Koblenz Fortress), France (Vauban’s fortifications), or Italy (e.g., the complex of forts around Verona), where the adaptation of military facilities to new social functions is based on broad heritage revitalization strategies [

36]. In light of these examples, the actions taken in Kraków are in line with the European trend of regenerating military heritage, although they require further systemic support, including in the development of uniform standards for managing facilities and assessing their social and cultural impact.

5. Simulation of Future Financing for 2025–2030

Assuming the continuation of the revitalization activities undertaken in 2020–2024 for the previously described facilities, a financing model can be created for the next four facilities, taking into account the increase in costs and possible sources of funds (

Table 3 and

Figure 7).

Simulation assumptions:

Cost increase: Average cost increase by 5% per year as a result of inflation and the increase in the cost of materials;

Financing division: Financing proportions remain consistent with the trends described so far;

New facilities: We take into account the possibility of revitalizing new facilities on a scale similar to Forts 52 and 52a.

Estimated costs of future projects based on Fort 31 “St. Benedict,” i.e.,:

Planned costs: PLN 21.5 million (5% increase in costs per year);

Sources: Municipal Budget (70%), SKOZK (10%), EU (20%).

New objects of the Kraków Fortress (x3):

The key conclusions regarding the sources of financing are as follows:

Share of EU funds: High participation in projects (PLN 30.8 million), which indicates effective acquisition of external financial resources;

Role of the Municipality of Kraków: The largest share in financing, which shows the importance of the involvement of local authorities in the revitalization of historical monuments;

Significance of SKOZK: Although the financial share of SKOZK is relatively low (PLN 11.5 million), the organization plays a key role in obtaining funds for the renovation of historical buildings.

The financial forecasts also take into account cost overruns or unforeseen expenses by using several predictors:

Cost increases by 5% per year—the basic safeguard against budget underestimation is the assumption of an average annual increase in costs resulting from inflation and rising prices of construction materials and services. This approach provides a buffer for predictable market changes;

Diversified sources of financing—maintaining the proportion of financing (Municipality, EU, SKOZK) allows for greater flexibility in allocating funds in the event of the need for budget shifts or seeking additional external support;

Financial reserve (implicit buffer)—although it is not indicated directly in the table, budget surpluses resulting from rounding costs and the assumption of slightly higher costs for some facilities (e.g., PLN 29 million for facility 3) can act as a safety buffer;

Possibility of investment staging—in the event of significant cost overruns, projects can be implemented in stages, which gives time to obtain additional funds or adjust the investment schedule.

The simulation does not include scenarios with reduced EU funds after 2030, but the financial data were verified by reference to previously implemented revitalization projects, such as Fort 31 “St. Benedict” and Forts 52 and 52a. The basis for estimating future costs and financing proportions was an analysis of actual financial outlays from 2020–2024, including project documentation, budget reports, and data from financing institutions (Budget of the Municipality of Kraków, SKOZK, and EU funds). The verification was based on:

Analysis of cost trends (taking into account the average annual increase of 5%);

Maintaining an analogous structure of financing sources as in completed projects, which allowed for the unification of the estimation model;

Consultations with entities responsible for the management of public and EU funds, which confirmed the possibility of continuing a similar co-financing model.

By using empirical data and maintaining consistency with the current proportions of sources, reliable financial estimates for the years 2025–2030 were obtained.

The key conclusions from the simulation indicate the dominant role of the Municipality of Kraków in financing revitalization projects and the high effectiveness of obtaining EU funds. The model, based on empirical data and maintaining the current proportions of financing sources, allowed for a realistic estimation of costs until 2030. The limitation of the analysis is the assumption of the constant share of EU funds, despite the uncertainty about their availability after 2030. Additionally, not taking into account political or economic changes may affect the limited durability of the forecast. It is suggested that future studies extend the model with pessimistic variants (e.g., a decrease in EU funding) and apply it to facilities in other historical cities, which will enable its validation and possible adaptation. It is also important to monitor the costs and effectiveness of investment staging in the event of budget overruns. The model can be successfully replicated in other cities with historic fortification complexes or post-industrial facilities requiring revitalization, e.g., “Modlin Fortress”. However, this requires adaptation to local financial conditions, institutional structure, the availability of external funds, and the involvement of local governments.

6. Summary

The amendment to the Revitalization Act of 29 July 2024 introduced a number of changes aimed at streamlining revitalization processes in Poland. One of the key elements is to clarify the definition of a degraded area and a revitalization area, which is intended to better target remedial actions. The amendment also introduces changes in the area of municipal revitalization programs, in the form of a number of important amendments. In the context of the Kraków Fortress facilities, which are an important element of the city’s cultural heritage, the amendment may have a significant impact on their revitalization processes. Thanks to more precise regulations, municipalities have the opportunity to plan and implement remedial actions more effectively, taking into account the specificity of such historic buildings.

The new regulations had a direct impact on eliminating significant formal and administrative barriers that previously slowed down or even prevented project implementation.

The most important changes and legal solutions:

Simplification of the procedure for adopting Municipal Revitalization Programs. The amendment reduced the number of required opinions and agreements, shortening the time from the start of planning work to the adoption of the program. This allowed for faster inclusion of new facilities (e.g., Forts 52 and 52a) in revitalization plans and enabled earlier application for funds from external funds;

Increased flexibility in the use of planning tools. The possibility of local modification of the provisions of local spatial development plans for the purposes of revitalization was introduced without the need to completely change them. Thanks to this, formalities were reduced when changing the function of historic buildings, which was previously a serious obstacle, e.g., when adapting forts;

Introduction of a simplified procedure for acquiring real estate for revitalization purposes. Municipalities have gained broader possibilities for temporarily taking over degraded objects (e.g., forts in poor technical condition) by way of lease or tenancy, which allows for preparatory activities to be carried out before full takeover of ownership;

Improved inter-institutional cooperation. The amendment obligated public institutions (such as SKOZK, the Voivodeship Conservator of Monuments) to consider applications as part of revitalization processes more quickly. This contributed to better synchronization of activities and more effective acquisition of funding, including from EU funds;

Extension of the catalogue of eligible costs. Thanks to the amendment, more types of expenses (e.g., related to the preparation of technical documentation or archaeological works) can be co-financed from EU and national funds. As a result, the financial efficiency of projects has improved, as can be seen in the presented simulation.

The amendment to the act of 2024 removed a number of formal barriers that previously hindered revitalization on a larger scale. It was thanks to these changes that it was possible to create a realistic model for financing revitalization projects for the facilities of the Kraków Fortress in the 2025–2030 perspective, with the participation of local government funds, EU funds, and SKOZK.

An example of the application of the above regulations can be the fort “St. Benedict”, for which public consultations were conducted, and then a functional and utility program was developed, providing for the adaptation of the facility to an educational function. Currently, as mentioned, work is underway on the renovation and adaptation project of this fort. The article attempts to describe the activities related to the expansion of the SSR borders, financing, and progress of works on the revitalization of the Kraków Fortress in the context of the guidelines for the protection of the cultural heritage of the historic area of the city of Kraków. The article also describes activities aimed at harmonizing factors such as promotion, education, and social participation.

In addition, the amendment to the Revitalization Act of 29 July 2024 is a breakthrough in the management of the revitalization of historic buildings in Poland. Procedural improvements, extension of the catalogue of eligible costs, and increased planning flexibility have enabled more effective implementation of revitalization projects, especially in relation to complex and dispersed heritage structures, such as the Kraków Fortress.

Key conclusions:

The reform has created a real legal and financial framework for the comprehensive revitalization of historic buildings.;

An interdisciplinary approach (spatial planning, heritage protection, social participation) increases the effectiveness of interventions;

Revitalization can be a development stimulus in peripheral areas of cities, thanks to the use of forts as educational, recreational, and cultural spaces.

Limitations:

The new regulations require a high level of institutional competence at the level of local governments—not every commune has the appropriate human and financial resources;

Despite formal simplifications, the processes of consultation with monument conservators are still time-consuming and may slow down the implementation of projects;

There are still no detailed guidelines for the adaptation of defensive structures to contemporary functions; therefore, good practices and guides are necessary.

Suggestions for future research and replication:

Comparative analysis of the implementation of the amendment in other cities with similar defensive structures (e.g., Modlin Fortress, Przemyśl Fortress, Poznań Citadel);

Research on the impact of social participation on the acceptance and durability of revitalization projects of military structures.

Development of model standards for the adaptation of forts for cultural and educational functions for use by other local governments.

Monitoring the effectiveness of the new system over a period of several years, in terms of costs, implementation time, and socio-economic effects.

7. Practical Recommendations and Policy Implications

The revitalization of the Kraków Fortress offers valuable lessons for other cities with historic military structures. First, interdisciplinary coordination is essential; urban planners, conservation officers, NGOs, and local governments must collaborate from the outset. Second, ensuring early community participation helps build long-term social support, avoiding conflicts and strengthening the relevance of new functions. Third, cities should develop local revitalization standards that integrate cultural heritage with sustainability goals, based on the Kraków model. From a policy perspective, national authorities should provide technical and legal assistance to municipalities with less capacity, including model procedures and training. The development of national or EU-level guidelines for adaptive reuse of military heritage would further support consistent implementation. Finally, financial instruments should reward projects that combine heritage protection with climate goals and social inclusion. By adopting these recommendations, cities can transform neglected historical sites into inclusive, sustainable public assets, supporting both cultural continuity and local development.