Hidden Actors of Urban Sustainability: Waste Pickers in Istanbul

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Climate Crisis and Waste Pickers

3. Waste Pickers in Istanbul: “Can Subaltern Speak?”

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection Techniques

4.2. Data Analysis Techniques

5. Reading Through Verbal Narrative Structures

5.1. Open Coding

5.2. Axial and Theoretical Coding

“Sometimes I have friends, I stay with them. Sometimes I stay outside if the weather is nice. If not, I’ll go to my cousin’s. There are times when I go to my hometown.”Participant Z (Figure 4).

“I am comfortable, yes. I built it myself. Everybody who comes here does it themselves. There is always a touch. That’s why he owns it. Otherwise, it is difficult, sister.”Participant Z. (Figure 4).

“Especially on wide streets, you wait for cars. And they swear.”Participant X. (Figure 5).

“There is freedom in this job. They can work as they want and at the hours they want.”Participant X. (Figure 5).

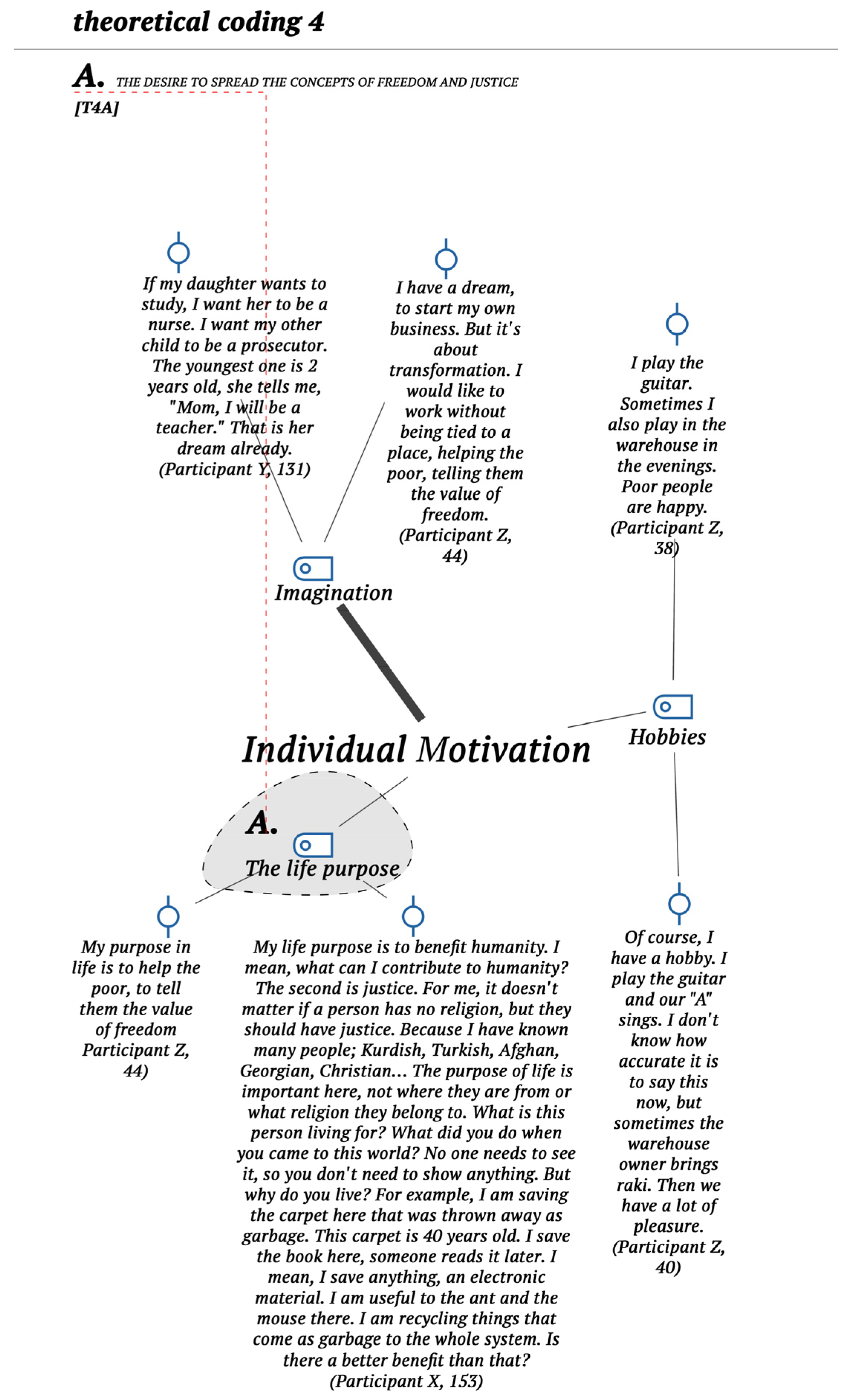

“My purpose in life is to help the poor, to tell them the value of freedom.”Participant X. (Figure 6).

“We finish work at 8:00 p.m. But sometimes we are late, no lie. Sometimes we stay until 10:00–11:00 p.m.”Participant Y. (Figure 7).

“Now, I have to give credit where it is due. I went through a lot of difficulties, but God knows this is my home now. I can live anywhere in Istanbul. You cannot, for example. If I say to you, Come and stay here, there is no way. You cannot. I think the real Istanbul belongs to waste pickers.”Participant X. (Figure 8).

“Sometimes I am like a car. I stop on red, I pass on green. You are something between a human and a car. Because your job is something with wheels on your back.”Participant Z. (Figure 8).

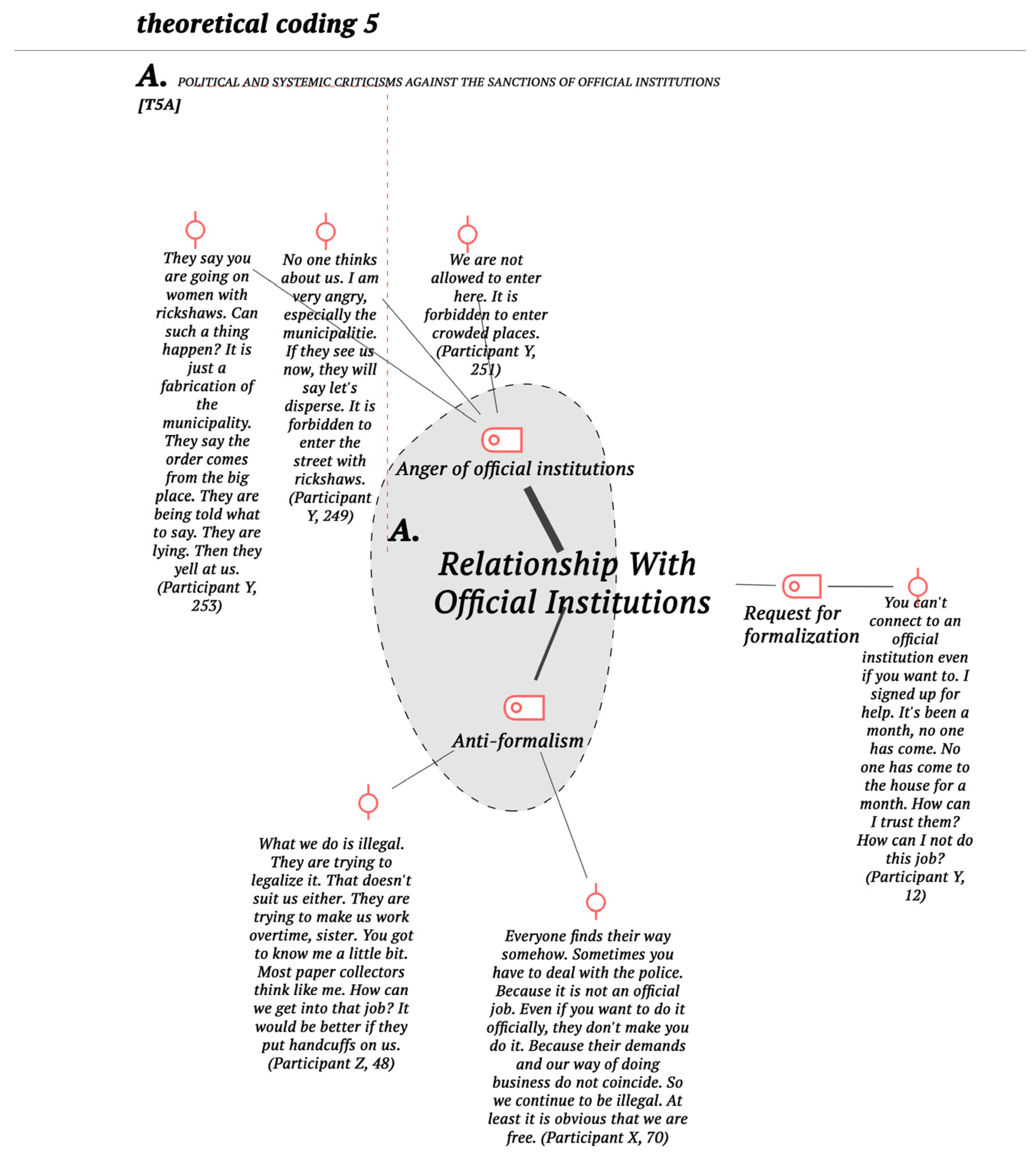

“No one thinks about us. I am very angry, especially with the municipality. If they see us now, they will say, let’s disperse. It is forbidden to enter the streets with rickshaws.”Participant Y. (Figure 9).

6. Reading Through Tactics of Producing Space

7. Conclusions

- Recognizing and legalizing nomadic lifestyles that are primarily in warehouses.

- Allowing selected spaces for warehouses to remain semi-structured and enabling users to decide on the organization and utilization of the space.

- Integrating waste collection into urban planning by ensuring warehouses are strategically placed where waste flow can be easily managed by waste pickers, considering the routes of waste collectors throughout the city, and after a joint decision-making process with waste collectors.

- Raising awareness among city dwellers about joining the fight for sustainability to combat marginalization.

- Educating local tradespeople to ensure materials such as paper, cardboard, plastic, and metal are kept in easily accessible locations.

- Establishing parallel communication channels with municipalities and supporting urban sustainability by ensuring bidirectional information flow.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gwebu, T.D. Population, Development, and Waste Management in Botswana: Conceptual and Policy Implications for Climate Change. Environ. Manag. 2003, 31, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V. Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buch, R.; Marseille, A.; Williams, M.; Aggarwal, R.; Sharma, A. From Waste Pickers to Producers: An Inclusive Circular Economy Solution through Development of Cooperatives in Waste Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.; Meegoda, J.N.; Ryu, S. Organic Waste Buyback as a Viable Method to Enhance Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management in Developing Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, M.M.; Juchelková, D. Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions: An alternative approach to waste management for reducing the environmental impacts in Myanmar. Environ. Eng. Res. 2019, 24, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velis, C.; Karl, C.V. Which Material Ownership and Responsibility in a Circular Economy? Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 773–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.M. Waste Pickers and Cities. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutberlet, J. Waste Picker Social Economy Organizations Addressing the Sustainable Development Goals. In Proceedings of the UNTFSSE International Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, 25–26 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sekubwa, B. The Role of Waste Pickers in Solid Waste Management for Sustainability in Developing Cities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Environmental Resilience and Livability in Cities—The Challenge of Climate Change, HERL 2022, Online, 20–21 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, J.; Corder, G.; Golev, A.; Lawson, L.; Ali, S. Global Review of Human Waste-Picking and Its Contribution to Poverty Alleviation and a Circular Economy. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 063002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mngomezulu, N.P.; Senekane, M.F. Methodology to Assess the Perception of Informal Waste Pickers on Being Integrated into the Waste Management System of the City of Ekurhuleni Municipality, Gauteng Province. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 16, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, C.J.; Blaauw, P.F.; Viljoen, J.M.; Swart, E.C. Exploring the Potential Health Risks Faced by Waste Pickers on Landfills in South Africa: A Socio-Ecological Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, J.-H.; Zapata, P.; De Azevedo, A.M.M.; Carenzo, S.; Charles, G.; Gutberlet, J.; Oloko, M.; Reynosa, J.P.; Campos, M.J.Z. Characteristics, challenges and innovations of Waste Picker Organizations: A Comparative Perspective Between Latin American and East African Countries. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, J.L.; Cano, N.S.d.S.L.; de Oliveira, J.F.D.; Rutkowski, E.W. How Much for an Inclusive and Solidary Selective Waste Collection? A Brazilian Study Case. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 985–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rincón, L.P.; De Arco-Canoles, O.D.C. Health and Working Conditions of Waste Pickers. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2021, 38, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, H.; Nalumu, D.J. Transforming Waste-Picking Landscape in Ghana: From Survival to Sustainable Enterprise. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibelli-Bianco, C.; Guimarães, J.P.S.; Yamane, L.H.; Siman, R.R. Education and Training: Key Solution to Self-Management and Economic Sustainability of Waste Pickers Organisations. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 40, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis-Filho, J.A.; Gutberlet, J.; Giarrizzo, T. Invisible Green Guardians: A long-term study on informal waste pickers’ contributions to recycling and the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 10, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senekane, M.F.; Mngomezulu, P.N. An Investigation of the Work Challenges Faced by Solid Waste Pickers in the City of Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality, Gauteng South Africa. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 17, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Guabiroba, R.C.; Jacobi, P.R.; Besen, G.R.; da Silva, M.A.V. Sustainability Performance Indicators: Improving Waste Picker Organizations in a Brazilian Region. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 3946–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, M.D.F.G.; Figueiredo, P.S.; Dantas, J. The socioeconomic Conditions of Waste pickers in Bahia, and an Evaluation of a Workforce Restructuring: A Multiple Case Study. Rev. Gest. Soc. E Ambient. 2017, 11, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Deus Chuquel da Silva, M.B.; Martins, B.R.; Simioni, F.J. Economic-Financial Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste Recycling in Brazil: A Case Study of a Recycling Cooperative. Fronteiras 2023, 12, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisolfi, V.; Chaves, G.d.L.D.; Siman, R.R.; Xavier, L.H. System dynamics applied to Closed Loop Supply Chains of Desktops and Laptops in Brazil: A Perspective for Social Inclusion of Waste Pickers. Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simatele, D.M.; Dlamini, S.; Kubanza, N. From Informality to Formality: Perspectives on the Challenges of Integrating Solid Waste Management into the Urban Development and Planning Policy in Johannesburg, South Africa. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Crespo, J.; Amaya-Rivas, J.L.; Ribeiro, I.; Soto, M.; Riel, A.; Zwolinski, P. Informal Waste Pickers in Guayaquil: Recycling Rates, Environmental Benefits, Main Barriers, and Troubles. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinberg, A.; Savain, R. Valuing Informal Integration: Inclusive Recycling in North Africa and the Middle East; GIZ, German International Co-operation: Eschborn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seager, J.; Rucevska, I. Gender in the modernisation of waste management: Key lessons from fieldwork in Bhutan, Mongolia, and Nepal. Gend. Dev. 2020, 28, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarthur, D.E. The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics & Catalysing Action; Ellen Macarthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C.; Krauth, T.; Wagner, S. Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12246–12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Jiménez, P.D.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric Transport and Deposition of Microplastics in a Remote Mountain Catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, I. Survival Tactics of Waste Paper Pickers in Istanbul. J. Ethn. Cult. Stud. 2015, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agdag, O.N. Comparison of Old and New Municipal Solid Waste Management Systems in Denizli. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Of Other Spaces. In Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postsivil Soceity; Dehaene, M., De Cauter, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, G.C. Can Subaltern Speak. In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture; Nelson, C., Grossberg, L., Eds.; Macmillan Education: Basingstoke, UK, 1988; pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Cupers, K. Towards a Nomadic Geography: Rethinking Space and Identity for the Potentials of Progressive Politics in the Contemporary City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobo, G.; Molle, A. Doing Ethnography; SAGE Publications: New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D.; Approaches, F.Q. Strategy: Four Qualitative Approaches. In Architectural Research Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 224–243. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; A Division of Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Building a Coding Frame; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G. Difference and Repetition; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| Field | Focus | References |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Science | Recycling, waste management, and urban sustainability | [1,2,7,9,10,12,13,14] |

| Public Health | Health risks, safety conditions | [12,15] |

| Social Sciences | Socio-economic conditions, motivations, and social stigma | [10,16,17,18,19] |

| Economics and Business | Economic viability, financial sustainability, and cooperative models | [3,4,6,8,20,21,22] |

| Urban Development and Policy | Integration into formal systems, impact of policies | [7,23,24,25,26] |

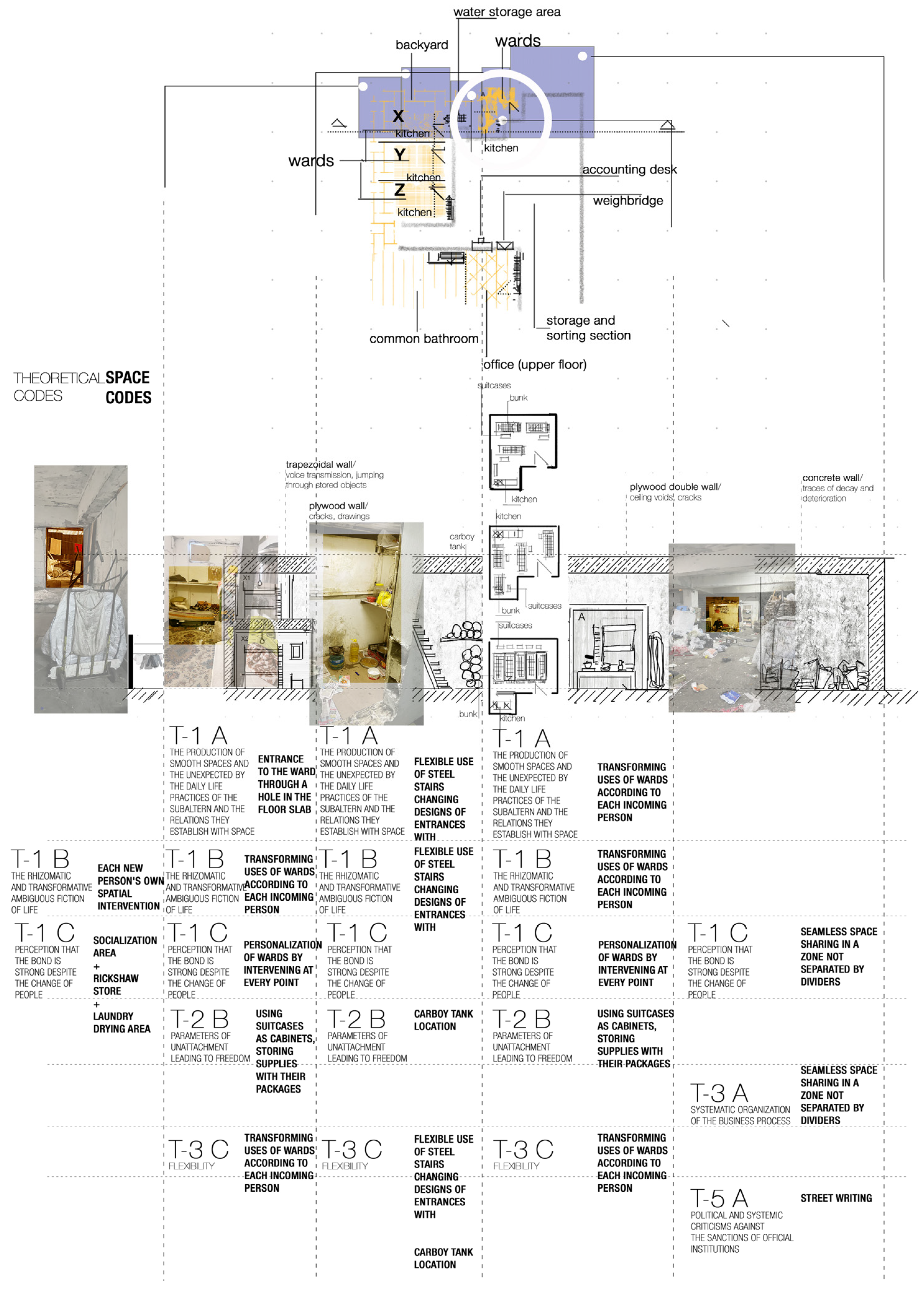

| Open Coding | Axial Coding | Theoretical Coding | Space Codes | Selective Coding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycling knowledge | The Intersection Between The City and Waste Picking | T6B-Generating critical grounds for recycling knowledge | Political Position | ||

| Definiton of streets | Street intersections | T6C-Effects of street morphology on body definition | |||

| Wide streets without sidewalks | |||||

| Being vehicle | |||||

| Definition of urban | Definition the city as home | T6A-The “unhomeliness” of the city due to variations in use | |||

| Definiton the city as work | |||||

| Values of Istanbul | |||||

| Interesting things found on the route | |||||

| Hobbies | Individual Motivation | ||||

| Imagination | |||||

| The life purpose | T4A-The desire to spread the concepts of freedom and justice | Political Position | |||

| Paper collectors’ connection with shopkeepers | Daily Life and Rhizomatic Situation | T1E-Perception of atrophy of the bond with shopkeepers | |||

| Paper collectors connection with each other | T1C-Perception that the bond is strong despite the change of people | The capacity of sections such as socializing area, rickshaw storage, and laundry drying to evolve with each newcomer, creating interpersonal bonds and personalization | |||

| Non-work activity | T1D-The perception that people are in charge of the temporal and spatial management of work and non-work activities | Rhizomatic Life Fiction | |||

| Toilet and shower use | |||||

| Frequency and location of life | Life only in the warehouse | T1B-The rhizomatic and transformative ambiguous fiction of life | Personalization of wards by intervening at every point | ||

| Life in the warehouse and in different locations | |||||

| Place attachment | T1A-The production of smooth spaces and the unexpected by the daily life practices of the subaltern and the relations they establish with space | Flexible use of steel stairs changing designs of entrances with Transforming uses of wards according to each incoming person | Rhizomatic Space Production | ||

| Room sharing | |||||

| Eating habits | Communal food production and eating | ||||

| Ward-by-ward food production and eating | |||||

| Individual food production and eating | |||||

| Anger of official institutions | Relationship With Official Institutions | T5A-Political and systemic criticisms against the sanctions of official institutions | Street writing | Political Position | |

| Request for formalization | |||||

| Anti-formalism | |||||

| Work potential | Absence of dependency | Perception of Waste Picking in Individuals | T2B-Parameters of unattachment leading to freedom | Using suitcases as cabinets, storage of supplies with their packages | Perception of Freedom |

| Freedom | |||||

| Problematic aspects of the work | Non-filling rickshaw | T2A-Problems causing mental and physical difficulties | |||

| Pounding | |||||

| Ostracism | |||||

| Swearword | |||||

| Changing road | |||||

| Illness | |||||

| Slope | |||||

| Atmospheric conditions | |||||

| Prohibition | |||||

| Garbage | |||||

| Route formation | Random route generation | Definition of Waste Picking | T3B-The effect of urban dynamics and street layout on route formation | ||

| Route formation through specific points | |||||

| Number of people working in warehouse | |||||

| Monetary dimension | Ways of using the wards that transform according to each incoming person | Rhizomatic Space Production | |||

| Working time | T3C-Flexibility | Seamless space sharing in a zone not separated by dividers | |||

| Work process | T3A-Systematic organization of the business process |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geçkili Karaman, P.; Şalgamcıoğlu, M.E. Hidden Actors of Urban Sustainability: Waste Pickers in Istanbul. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146236

Geçkili Karaman P, Şalgamcıoğlu ME. Hidden Actors of Urban Sustainability: Waste Pickers in Istanbul. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146236

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeçkili Karaman, Pınar, and Mehmet Emin Şalgamcıoğlu. 2025. "Hidden Actors of Urban Sustainability: Waste Pickers in Istanbul" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146236

APA StyleGeçkili Karaman, P., & Şalgamcıoğlu, M. E. (2025). Hidden Actors of Urban Sustainability: Waste Pickers in Istanbul. Sustainability, 17(14), 6236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146236