Virtual Influencers and Sustainable Brand Relationships: Understanding Consumer Commitment and Behavioral Intentions in Digital Marketing for Environmental Stewardship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Virtual Influencer Marketing and Sustainable Marketing Paradigms

2.2. Theoretical Framework Enhancement

2.3. Virtual Influencer Characteristics

2.4. Relationship Commitment

2.5. Consumer Innovativeness

3. Hypotheses and Research Model

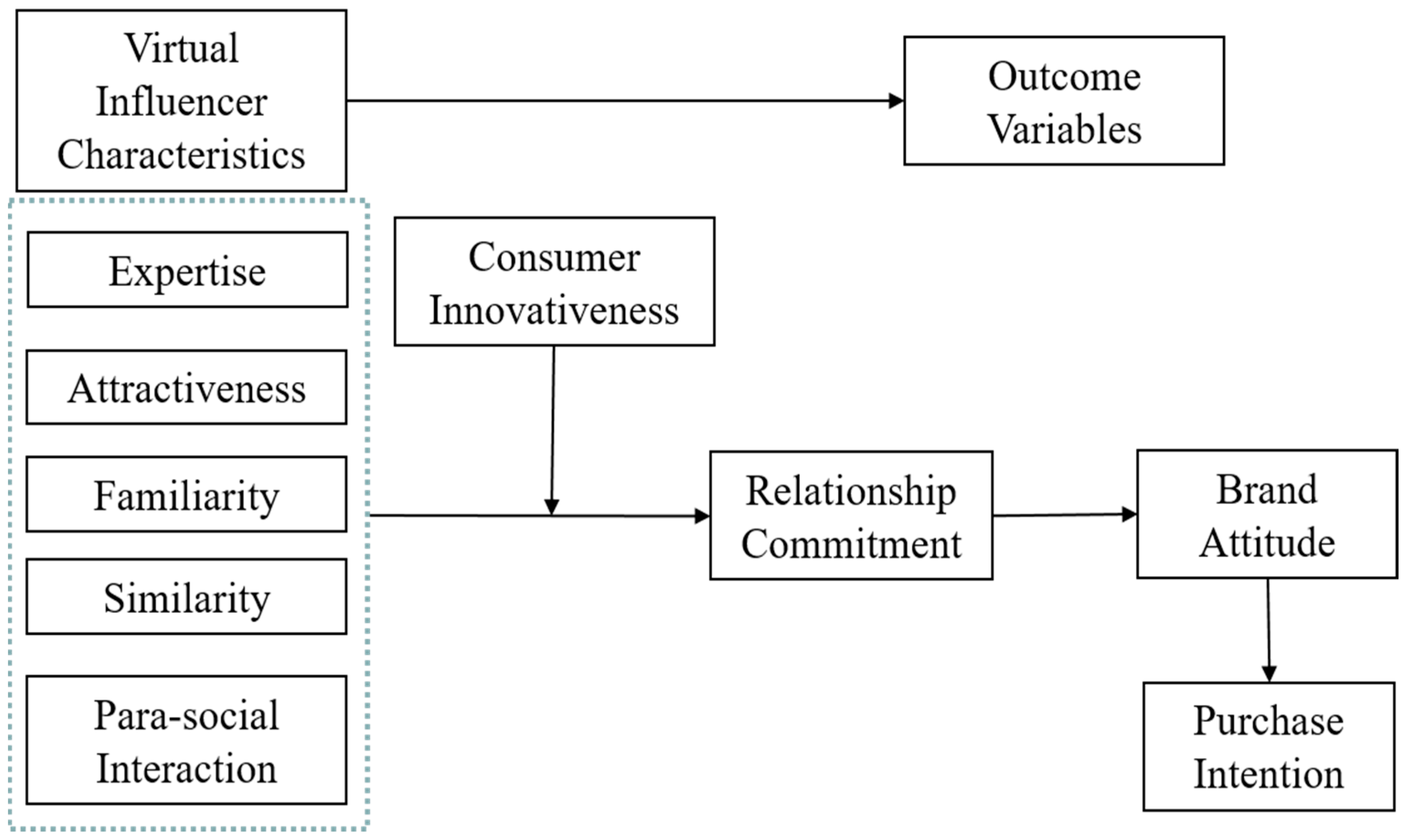

3.1. Suggested Research Model

3.2. Research Hypotheses

4. Method

4.1. Operational Definitions and Measurement

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Measurement Scale Standardization and Validation Protocols

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Validity and Reliability Analysis

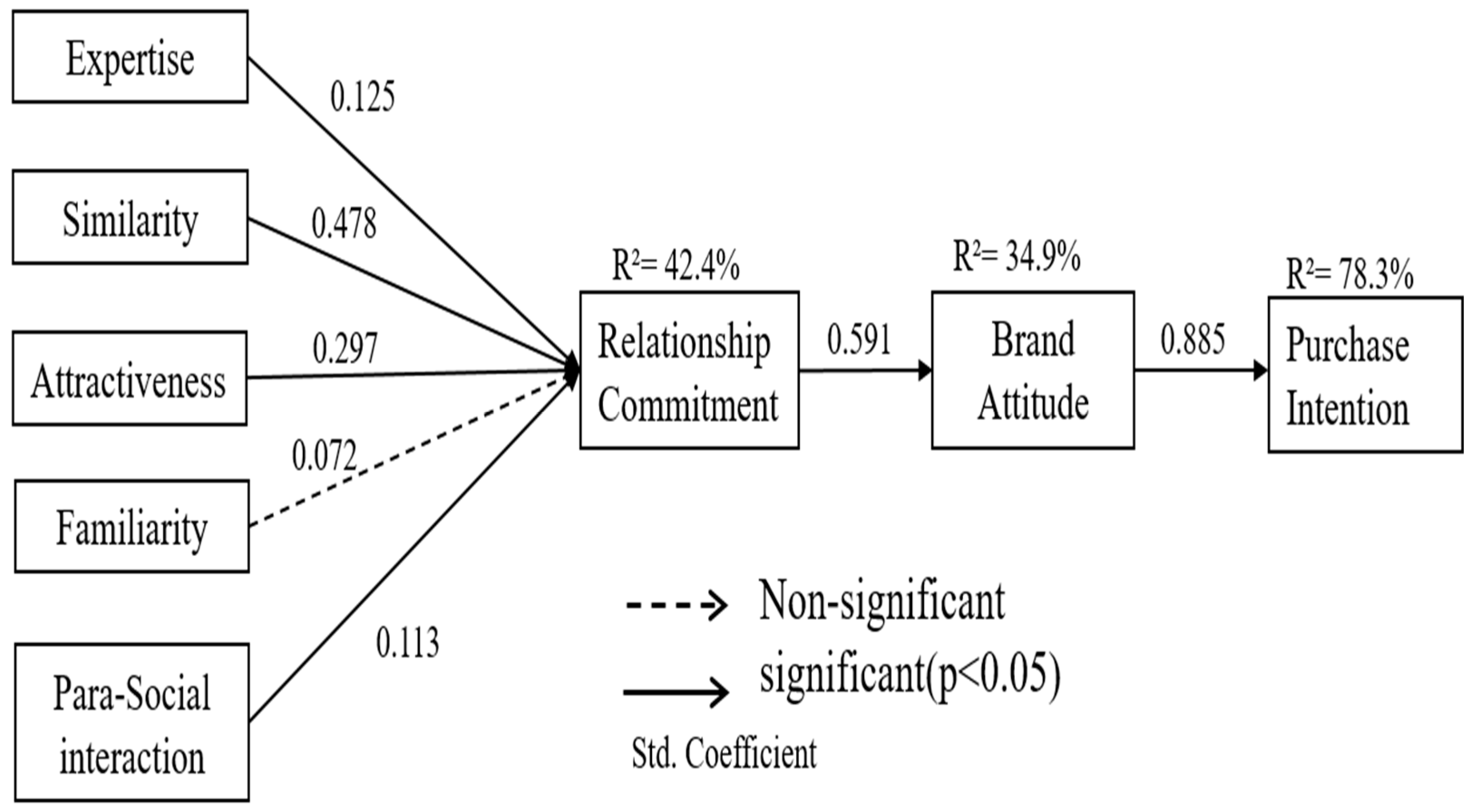

5.3. Structural Equation Modeling

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Sustainable Marketing Implications and Environmental Impact

7. Theoretical and Practical Implications of Virtual Influencer Research

7.1. Comprehensive Managerial Implications and Strategic Frameworks

7.2. Societal Impact Analysis and Broader Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Imperatives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Statistics of the Construct Items

| Construct | Survey Measures |

| Expertise | I believe this virtual influencer possesses sufficient knowledge about products/services?” |

| I consider this virtual influencer qualified as an expert in their field? | |

| I find the information provided by this virtual influencer to be credible? | |

| I believe this virtual influencer has the capacity to provide professional advice? | |

| Similarity | I believe this virtual influencer shares similar values with you? |

| I think this virtual influencer maintains a lifestyle similar to yours?” | |

| I find this virtual influencer’s thought processes and behavioral patterns similar to yours? | |

| I believe this virtual influencer shares similar interests with you? | |

| Attractiveness | I find this virtual influencer’s appearance attractive? |

| I consider this virtual influencer’s style to be sophisticated? | |

| I find this virtual influencer’s image appealing? | |

| I find this virtual influencer’s overall appearance attractive? | |

| Familiarity | I am familiar with this virtual influencer’s content and messaging style |

| I feel comfortable with this virtual influencer’s digital presence and personality. | |

| I perceive this virtual influencer as a recognizable entity in my digital environment | |

| I have developed a sense of familiarity with this virtual influencer’s characteristics over time. | |

| Par-social interaction | I feel natural when watching [virtual influencer name]’s content, as if I’m having a conversation with a real friend. |

| The daily life and thoughts that [virtual influencer name] shares feel authentic to me. | |

| I often feel the urge to comment on [virtual influencer name]’s posts or send them messages. | |

| Relationship Commitment | I want to maintain a lasting relationship with this virtual influencer |

| I am committed to maintaining my relationship with this virtual influencer | |

| My relationship with this virtual influencer means a lot to me. | |

| Brand Attitude | I have a positive perception towards brands endorsed by virtual influencers.” |

| I feel favorably disposed towards brands utilized by virtual influencers.” | |

| I find brands associated with virtual influencers appealing. | |

| I perceive brands endorsed by virtual influencers as credible. | |

| Purchase Intention | I am inclined to purchase products endorsed by virtual influencers |

| When considering products within the same category, I am more likely to purchase those promoted by virtual influencers. | |

| I would recommend products endorsed by virtual influencers to others. | |

| Consumer Innovativeness | I think I can manage unexpected events efficiently |

| I believe I can resolve challenging tasks if I make an effort | |

| I am confident that I can accomplish any objective I pursue. |

References

- Varsamis, E. Are Social Media Influencers The Next-Generation Brand Ambassadors? Forbes 2018, 13. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2018/06/13/are-social-media-influencers-the-next-generation-brand-ambassadors/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Ma, Y.; Li, J. How humanlike is enough?: Uncovering the underlying mechanism of virtual influencer endorsement. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2024, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Trioni, P.P. Virtual influencers in online social media. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanaarachchi, G.; Viglia, G.; Kurtaliqi, F. Privacy in hospitality: Managing biometric and biographic data with immersive technology. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 3823–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Williams, K. Digital sustainability in influencer marketing: Environmental impact assessment of virtual versus human brand ambassadors. J. Sustain. Mark. 2024, 8, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M.; Thompson, A. Carbon footprint analysis of virtual influencer campaigns: A comparative study. Environ. Mark. Q. 2024, 12, 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, S. Environmental consciousness and digital brand engagement: The role of virtual influencers in sustainable marketing. Sustain. Consum. Prod. 2024, 35, 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z. Shall brands create their own virtual influencers? A comprehensive study of 33 virtual influencers on Instagram. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrath, M.H.E.E.; Olya, H.; Shah, Z.; Li, H. Virtual influencers and pro-environmental causes: The roles of message warmth and trust in experts. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 175, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santora, J. What are virtual influencers and how do they work. Influ. Mark. Hub 2024. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/what-are-virtual-influencers// (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Aghadjanian, N. Gartner’s 2022 Marketing Predictions on Virtual Influencers, Employee Advocacy and More; AList Daily: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.; Davidson, R. Virtual influencers and environmental responsibility: Redefining sustainable marketing practices. Corp. Environ. Strategy 2023, 19, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, N. Digital sustainability frameworks in influencer marketing: Virtual ambassadors and environmental impact reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 387, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; White, M. Consumer demand for sustainable brand practices: The virtual influencer advantage. Sustain. Bus. Int. J. 2024, 41, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Brown, T. Environmental accountability in digital marketing: Virtual influencers and sustainable brand communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 178, 445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. When digital celebrity talks to you: How human-like virtual influencers satisfy consumer’s experience through social presence on social media endorsements. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H.H. Understanding consumer-brand relationships in the digital age: The role of psychological ownership. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 354–365. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Smith, T. Micro vs. macro-influencers: Analyzing engagement metrics and marketing outcomes. Soc. Media Mark. J. 2023, 19, 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. The power of authenticity: How influencer marketing shapes consumer behavior. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2023, 12, 145–163. [Google Scholar]

- Musiyiwa, R.; Jacobson, J. Leveraging Influencer Relations Professionals for Sponsorship Disclosure in Social Media Influencer Marketing. J. Interact. Advert. 2024, 24, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungruangjit, W.; Mongkol, K.; Piriyakul, I.; Charoenpornpanichkul, K. The power of human-like virtual-influencer-generated content: Impact on consumers’ willingness to follow and purchase intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 16, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló Ariño, L.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez Sánchez, S. Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M.; Matos, M. Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Leung, W.F. Virtual influencer as celebrity endorsers. Univ. South Fla. (USF) M3 Publ. 2021, 5, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Jhawar, A.; Kumar, P.; Varshney, S. The emergence of virtual influencers: A shift in the influencer marketing paradigm. Young Consum. 2023, 24, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, A. Impacts of consumer innovativeness on the intention to purchase sustainable products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Johnson, C. Sustainable marketing paradigms and virtual brand ambassadors: A theoretical framework. Mark. Theory 2024, 24, 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.; Davis, K. Digital-first sustainability: Virtual influencers and environmental marketing innovation. Innov. Mark. 2023, 19, 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.; Martinez, L. Environmental impact assessment of virtual versus traditional influencer marketing strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 325, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B.; Evans, S. Carbon footprint reduction through virtual influencer adoption: A sustainability analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 045–062. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.; Turner, G. Sustainable digital marketing: Virtual influencers and environmental responsibility frameworks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.; Roberts, J. Authenticity in sustainability communication: Virtual influencers versus human brand ambassadors. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, R.; Bhoumik, K.; Thompson, J. Investigating the effectiveness of virtual influencers in prosocial marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 2121–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.; Walker, D. Stakeholder capitalism and virtual influencer marketing: Environmental implications. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 175, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.; Phillips, R. Greenwashing risks and virtual influencer marketing: A mitigation framework. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2024, 27, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Lewis, A. Sustainability messaging consistency through virtual brand ambassadors. J. Advert. Res. 2024, 64, 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C.; Scott, N. Consumer evaluation of brand sustainability through digital touchpoints. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L.; King, P. Digital sustainability communication and consumer brand relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 152, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, T.; Hill, S. Authentic sustainability communication in virtual influencer marketing. J. Mark. Commun. 2024, 30, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Sakib, M.N.; Zolfagharian, M.; Yazdanparast, A. Does parasocial interaction with weight loss vloggers affect compliance? The role of vlogger characteristics, consumer readiness, and health consciousness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; Van Reijmersdal, E.A. Disclosing influencer marketing on YouTube to children: The moderating role of Para-social relationship. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, W. Investigating motivated consumer innovativeness in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista da Silva Oliveira, A.; Chimenti, P. Humanized Robots: A Proposition of Categories to Understand Virtual Influencers. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close encounters of the AI kind: Use of AI influencers as brand endorsers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, V.; Sobek, T. Virtual Avatars, Virtual Influencers, & Authenticity: A Qualitative Study from A Consumer Perspective. Master’s Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Potdevin, D.; Clavel, C.; Sabouret, N. A virtual tourist counselor expressing intimacy behaviors: A new perspective to create emotion in visitors and offer them a better user experience? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 150, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-aho, V. ‘You really are a great big sister’—Parasocial relationships, credibility, and the moderating role of audience comments in influencer marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Consumer Behavior and Strategic Business Applications. Adv. Econ. Manag. Polit. Sci. 2024, 86, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. Meta-analysis of social media influencer impact: Key antecedents and theoretical foundations. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 394–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Wu, L.; Chang, Y.; Hong, R. Influencers on Social Media as References: Understanding the Importance of Parasocial Relationships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.L.; Liebers, N.; Abt, M. The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: How influencer-brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 2019, 62, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Cuevas, L.M.; Chong, S.M.; Lim, H. Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, F.J.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Fernández Giordano, M.; Lopez-Lopez, D. Behind influencer marketing: Key marketing decisions and their effects on followers’ responses. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 579–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Zhang, Q. Influence of para-social relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X. The role of relationship commitment in customer loyalty: Evidence from digital platforms. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2020, 30, 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, S. The impact of brand authenticity on relationship commitment: The mediating role of emotional connection. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Thompson, R. The influence of relationship commitment on customer loyalty in digital marketplaces. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Brown, B. Relationship commitment in virtual communities: The role of social presence. J. Interact. Mark. 2023, 55, 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Alalwan, A. Investigating the impact of social media advertising features on customer purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C. The Role of Product Originality, Usefulness and Motivated Consumer Innovativeness in New Product Adoption Intentions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Bowman, N.D. Avatars are (sometimes) people too: Linguistic indicators of parasocial and social ties in player-avatar relationships. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusmussen, L. Parasocial interaction in the digital age: An examination of relationship building and the effectiveness of YouTube celebrities. J. Soc. Media Soc. 2018, 7, 280–294. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, H.C. Laughing matters: Exploring ridicule-related traits, personality, and well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2024, 227, 112704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; David, M.E.; George, M. Types of Consumer-Brand Relationships: A systematic review and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Guang, L.; Zafar, M.; Shahzad, F.; Shahbaz, M.; Lateef, M. Consumers’ purchase intention and decision-making process through social networking sites: A social commerce construct. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 40, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, G.J.; Yin, E.; Bell, S. Global Consumer Innovativeness: Cross-Country Differences and Demographic Commonalities. J. Int. Mark. 2009, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.; Gray, M. Environmental consciousness and brand evaluation in digital marketing contexts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, D.; Morgan, K. Sustainability messaging authenticity and consumer trust formation. J. Consum. Aff. 2024, 58, 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.; Bell, A. Virtual influencers and sustainable brand relationships: A consumer behavior analysis. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, B.; Carter, E. Environmental sustainability priorities and digital marketing receptivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 179, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, G.; Price, H. Digital-first marketing strategies and environmental consumer behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 388, 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, L.; Nash, M. Sustainable marketing theory and virtual influencer applications. Mark. Theory 2024, 24, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, S.; Reid, P. Environmental responsibility principles in digital advertising frameworks. J. Advert. 2024, 53, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.; Stone, J. Ecological footprint reduction through virtual marketing strategies. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 218, 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.; Ward, L. Authenticity paradoxes in virtual environmental communication. Commun. Res. 2024, 51, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, K.; Shaw, N. Lifestyle congruence and sustainability messaging effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 2024, 50, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, M.; Cross, R. Environmental credibility and virtual brand ambassador effectiveness. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2024, 29, 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, D.; Harper, S. Consumer innovativeness and environmental brand relationship formation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2024, 41, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, G.; Fisher, T. Environmental consciousness and virtual influencer receptivity. Environ. Behav. 2024, 56, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, A.; Graham, P. Technological solutions and environmental challenge acceptance. Technol. Soc. 2024, 76, 178–195. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.; Barnes, C. Sustainable consumption behaviors and virtual influencer marketing effectiveness. J. Consum. Policy 2024, 47, 234–251. [Google Scholar]

| Index (n = 650) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Man | 280 | 43.1 |

| Female | 370 | 56.9 |

| Years | ||

| 20–29 | 177 | 27.2 |

| 30–39 | 257 | 39.6 |

| 40–49 | 163 | 25.0 |

| Over 50 | 53 | 7.8 |

| Education Level | ||

| High school degree | 51 | 7.8 |

| College students | 226 | 34.7 |

| College degree | 245 | 37.7 |

| Graduate school degree | 128 | 19.8 |

| Occupation | ||

| Employee | 271 | 41.7 |

| Public office | 155 | 23.9 |

| Self-employment | 94 | 14.5 |

| Students | 90 | 13.9 |

| House keeper | 40 | 6.0 |

| Monthly income in USD | ||

| below $2000 | 33 | 5.0 |

| 2000~3000 | 111 | 17.0 |

| 3000~4000 | 259 | 39.9 |

| 4000~5000 | 163 | 25.0 |

| Above $5000 | 84 | 13.1 |

| Average Shopping time per week | ||

| Below 1 h | 78 | 12.0 |

| 1–3 | 123 | 18.9 |

| 3–5 | 207 | 31.9 |

| 5–7 | 169 | 26.0 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loadings | Eigen Value | Variance (%) | Ave | Composite Reliability | (Cronbach’s Alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expertise | EX1 | 0.660 | 9.308 | 46.602 | 0.771 | 0.931 | 0.812 |

| EX2 | 0.620 | ||||||

| EX3 | 0.680 | ||||||

| EX4 | 0.637 | ||||||

| Similarity | SI1 | 0.728 | 3.901 | 14.307 | 0.667 | 0.871 | 0.821 |

| SI2 | 0.857 | ||||||

| SI3 | 0.830 | ||||||

| SI4 | 0.817 | ||||||

| Attractiveness | AT1 | 0.611 | 3.252 | 7.045 | 0.762 | 0.901 | 0.847 |

| AT2 | 0.601 | ||||||

| AT3 | 0.687 | ||||||

| AT4 | 0.731 | ||||||

| Familiarity | FA1 | 0.734 | 1.985 | 4.280 | 0.791 | 0.792 | 0.843 |

| FA2 | 0.780 | ||||||

| FA3 | 0.669 | ||||||

| FA4 | 0.665 | ||||||

| Para-Social Interaction | PAI1 | 0.792 | 1.346 | 3.675 | 0.761 | 0.873 | 0.845 |

| PAI2 | 0.759 | ||||||

| PAI3 | 0.788 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loadings | Eigen Value | Variance (%) | Ave | Composite Reliability | (Cronbach’s Alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship Commitment | co1 | 0.813 | 9.883 | 62.496 | 0.765 | 0.831 | 0.817 |

| co2 | 0.787 | ||||||

| co3 | 0.577 | ||||||

| Brand Attitude | ba1 | 0.658 | 3.629 | 9.883 | 0.782 | 0.792 | 0.803 |

| ba2 | 0.684 | ||||||

| ba3 | 0.785 | ||||||

| ba4 | 0.730 | ||||||

| Purchase Intention | pi1 | 0.749 | 1.947 | 6.144 | 0.883 | 0.801 | 0.823 |

| pi2 | 0.654 | ||||||

| pi3 | 0.807 | ||||||

| Consumer Innovativeness | ci1 | 0.717 | 1.421 | 4.629 | 0.851 | 0.857 | 0.836 |

| ci2 | 0.801 | ||||||

| ci3 | 0.764 |

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX | 0.594 | ||||||||

| SI | 0.05 | 0.445 | |||||||

| AT | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.581 | ||||||

| FA | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.626 | |||||

| PAI | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.575 | ||||

| RC | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.585 | |||

| BT | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.612 | ||

| PI | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.038 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.694 | |

| CI | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.116 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.724 |

| H | Paths | Std. Coefficient | S.E | Z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Expertise → Commitment | 0.125 | 0.069 | 2.089 | 0.037 |

| H2 | Similarity → Commitment | 0.478 | 0.047 | 9.677 | 0.000 |

| H3 | Attractiveness → Commitment | 0.297 | 0.055 | 5.891 | 0.000 |

| H4 | Familiarity → Commitment | 0.072 | 0.053 | 1.584 | 0.114 |

| H5 | Par-social Interaction → Commitment | 0.113 | 0.057 | 1.982 | 0.041 |

| H6 | Commitment → Brand Attitude | 0.591 | 0.034 | 19.04 | 0.000 |

| H7 | Brand → Purchase Intention | 0.885 | 0.017 | 49.34 | 0.000 |

| H | Path | Estimate | S.E (Standard Errors) | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating Variable: Consumer Innovativeness | |||||

| H8-1 | Expertise → Relationship Commitment | 0.141 | 0.032 | 2.751 | 0.000 |

| H8-2 | Similarity → Relationship Commitment | 0.214 | 0.035 | 6.003 | 0.000 |

| H8-3 | Attractiveness → Relationship Commitment | 0.462 | 0.038 | 10.196 | 0.000 |

| H8-4 | Familiarity → Relationship Commitment | 0.102 | 0.036 | 2.942 | 0.003 |

| H8-5 | Para-social Interaction → Relationship Commitment | 0.352 | 0.038 | 7.750 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diao, Y.; Liang, M.; Jin, C.; Woo, H. Virtual Influencers and Sustainable Brand Relationships: Understanding Consumer Commitment and Behavioral Intentions in Digital Marketing for Environmental Stewardship. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136187

Diao Y, Liang M, Jin C, Woo H. Virtual Influencers and Sustainable Brand Relationships: Understanding Consumer Commitment and Behavioral Intentions in Digital Marketing for Environmental Stewardship. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136187

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiao, Yu, Meili Liang, ChangHyun Jin, and HyunKyung Woo. 2025. "Virtual Influencers and Sustainable Brand Relationships: Understanding Consumer Commitment and Behavioral Intentions in Digital Marketing for Environmental Stewardship" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136187

APA StyleDiao, Y., Liang, M., Jin, C., & Woo, H. (2025). Virtual Influencers and Sustainable Brand Relationships: Understanding Consumer Commitment and Behavioral Intentions in Digital Marketing for Environmental Stewardship. Sustainability, 17(13), 6187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136187

_Li.png)