Abstract

This study examines the behavioral mechanism of sustainable consumption through which greenwashing (GW) perception influences consumers’ intention to purchase green food, with a particular focus on Chinese consumers. Grounded in the value-based adoption model (VAM), we propose a structural model that incorporates perceived benefit (PB) and perceived sacrifice (PS) as mediating variables and GW perception as a moderating variable. Using survey data from 347 Chinese respondents, the analysis is conducted via partial least squares structural equation modeling. The results indicate that environmental knowledge, environmental awareness (EA), green food characteristics (GFCs), and consumer characteristics significantly enhance PB, whereas EA and GFCs reduce PS. PB has a positive effect on green food purchase intention, whereas PS has a negative effect. Notably, GW perception does not significantly moderate the relationship between PB and purchase intention, but it does intensify the negative impact of PS on purchase intention. This suggests that consumers who are sensitive to GW are more likely to reject green food products when they experience a high PS. This study contributes to the literature by extending the application of the VAM in the context of sustainable consumption and offering empirical insights into the psychological effects of GW. Practical implications include marketing strategies aimed at reducing PS and fostering trust through transparent, verifiable green claims. Policymakers are encouraged to improve certification systems and public education efforts to alleviate consumer skepticism in the green food market.

1. Introduction

Environmental issues are no longer matters that individuals, corporations, or even nations can ignore or avoid. Rather, the environment has become a central axis permeating the entire social system, extending far beyond mere eco-friendliness. As micro-actors within the broader environmental dynamic, consumers play a crucial role as practical agents in addressing environmental challenges. Among various eco-consumption concerns, interest in green food, which is closely tied to personal health, has been growing at a particularly rapid pace [1]. This rising consumer interest presents new challenges for firms and industries in terms of production, marketing, and customer engagement. In response, companies have adopted production methods using high-quality raw materials and eco-friendly energy, while also developing marketing strategies that emphasize environmental and social contributions and promote health-enhancing brand images. However, the increased demand for green food and the evolution of related production and marketing techniques do not necessarily translate into stronger consumer purchase intentions. In particular, deliberate and exaggerated greenwashing (GW) practices by companies can erode consumer trust and reduce purchase motivation [2].

The intersection of green food and GW is especially critical in the Chinese market. Since 2010, China has experienced rapid economic growth, leading to increased purchasing power and a shift toward both luxury and eco-friendly consumption. Nonetheless, green consumption in China has largely emerged as a reactive behavior, shaped by limited information and distrust toward inexpensive domestic products. A structural asymmetry between green product supply and consumer demand continues to persist. Within this environment, companies have increasingly resorted to GW (i.e., making exaggerated or false eco-friendly claims) as a more accessible alternative to genuinely transforming the environmental quality of their products or services. In China, the circulation of products and advertisements has operated under loosely defined and lenient regulatory frameworks, rather than strict and standardized controls, resulting in relatively low public awareness of GW. Moreover, both government and industry stakeholders have historically prioritized growth-oriented economic and industrial policies, resisting strict environmental regulations that could potentially hinder industrial productivity. This resistance has further enabled the proliferation of GW practices.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, Chinese consumers have become more focused on health-related issues, contributing to heightened interest in safe and environmentally friendly food products. The rapid transition toward a smart society and the advancement of e-commerce platforms have improved accessibility to green food. Simultaneously, rising consumer awareness, environmental knowledge (EK), and access to information have produced a growing population of discerning, well-informed consumers who are increasingly capable of detecting GW. Chinese consumers now have access to a broad range of green food options (e.g., organic, chemical-free, and eco-cultivated) and are undergoing a transitional phase in which they learn to distinguish genuine green products from greenwashed alternatives. In this context, it has become increasingly important to investigate, from a multidimensional and structural perspective, how GW affects consumers’ intentions to purchase green food. Although previous studies on green food have examined various product-related attributes (e.g., brand trust, ingredients, and labeling) and consumer-related factors (e.g., perceived benefit (PB) and perceived sacrifice (PS)), much of this research has focused on identifying psychological and cognitive predictors of purchase intention. To address this gap, the present study conducts a structural analysis of Chinese consumers’ intention to purchase green food, going beyond individual cognition to consider the moderating role of GW perception. This approach offers insight into whether GW serves as a meaningful criterion for consumers in the Chinese market when evaluating and differentiating between exaggerated and genuinely eco-friendly food products.

This study integrates several psychological constructs to explain consumer behavior in the context of green food consumption. Although environmental knowledge and environmental awareness are conceptually related, they differ in focus and function. Environmental knowledge refers to the individual’s cognitive understanding of environmental issues, including factual and procedural knowledge [3], whereas environmental awareness reflects an individual’s emotional engagement, concern, and attitude toward environmental protection [4].

Furthermore, two value-oriented constructs—perceived benefit and perceived sacrifice—are used to assess consumer evaluations of green products. Perceived benefit refers to the favorable outcomes a consumer expects to receive, such as health advantages, social value, or environmental impact [5]. In contrast, perceived sacrifice reflects the perceived costs associated with green purchases, including monetary price, time, and cognitive effort [6]. These constructs provide a balanced framework for understanding the trade-offs consumers face in sustainable consumption decisions.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical background and identifies key factors influencing green food purchase intention (GFPI), which serve as the basis for hypothesis development. Section 3 presents the research model, outlines the structural relationships among variables derived from the literature, and describes the survey instrument and data collection process. Section 4 details the empirical results, including demographic analysis, structural equation modeling, and moderation analysis of GW. Finally, Section 5 discusses the academic and managerial implications of the findings, followed by this study’s conclusion and limitations in Section 6.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. EK

EK is a key psychological factor influencing green consumption behavior. It refers to the extent to which consumers are aware of environmental problems and the ecological changes they bring about, reflecting their comprehension of environmental information [7]. EK involves more than the simple acquisition of factual knowledge; it serves as a cognitive foundation that increases the likelihood of consumers engaging in environmentally responsible behaviors.

Previous studies generally categorized EK into three types [8]. First, system knowledge refers to a general understanding of broad environmental issues such as climate change and resource depletion. Second, action-related knowledge consists of specific, practical information about behaviors like recycling and energy conservation. Third, effectiveness knowledge involves understanding how those behaviors impact the environment, reflecting an outcome-oriented awareness. Importantly, EK plays a significant role not only in shaping general environmental attitudes but also in influencing actual purchasing behavior. According to Roczen et al. [9] and Boeve-de Pauw & Van Pelegem [10], consumers with higher levels of EK tend to show greater interest in and acceptance of eco-friendly products. The recent literature further distinguishes between subjective knowledge (self-assessed understanding) and objective knowledge (accurate factual knowledge) when analyzing their respective effects on consumer behavior [11]. For example, Joshi and Roman [12] argued that consumers with a higher degree of environmental understanding are more inclined to purchase green products. In other words, well-informed consumers (i.e., those aware of the benefits and attributes of eco-friendly products) tend to exhibit more proactive purchasing behaviors.

EK is also considered a critical antecedent of PB in the context of green consumption. Consumers with high EK levels are better equipped to recognize the personal and societal benefits of green products, including economic savings, health protection, and environmental sustainability [13]. Extending this logic, Tan [14] suggested that EK positively influences consumer values and significantly affects not only green product adoption but also environmentally oriented behaviors such as staying at eco-friendly hotels. EK enhances perceptions of both functional and emotional value, thereby reinforcing favorable evaluations of green consumption [15]. Additionally, recent studies have shown that EK increases consumers’ perceived value of green products and lowers their perception of product-related risk, ultimately leading to stronger purchase intentions [16].

Similarly, EK plays an important role in reducing the PS associated with selecting green products [17]. Consumers with higher levels of EK are better able to understand the environmental and social value offered by such products. This deeper understanding makes them less sensitive to potential drawbacks such as higher prices or functional inconvenience [18]. Moreover, EK can lead consumers to perceive sacrifice not merely as a financial or practical burden but as a necessary contribution to environmental protection, thus reducing negative attitudes and psychological resistance toward eco-friendly products [19]. Prior research has also identified additional factors that reduce PS, such as moral self-identity [20] and knowledge of corporate social responsibility [21]. Taken together, these findings suggest that EK fosters a stronger appreciation for eco-friendly behavior and makes consumers more willing to accept the costs or inconveniences associated with green consumption.

Given that green food constitutes a major category of green products, the present study proposes the following hypotheses, based on prior research, regarding the relationship between EK and both PB and PS:

H1.

EK has a positive effect on consumer PB.

H2.

EK has a negative effect on consumer PS.

2.2. EA

EA is a comprehensive concept encompassing consumers’ recognition of environmental problems, along with their attitudes and sense of responsibility toward them [4]. Generally, EA manifests across three dimensions: concern for the environment, attitudes toward the environment, and a sense of environmental responsibility. First, environmental attitudes reflect individuals’ perceived importance of, and concern for, ecological issues such as pollution and climate change [22]. Consumer groups with high levels of environmental concern are more likely to actively participate in environmental protection efforts and show stronger intentions to engage in green consumption [23]. Second, consumers who hold positive environmental attitudes are more inclined to practice eco-friendly behaviors (e.g., recycling and minimizing disposable product use) and exhibit greater interest in and intention to purchase green products compared to the general population [24]. Finally, environmental responsibility is closely tied to individuals’ moral obligation to protect the environment and has been widely recognized as a psychological driver of green behavior in TPB-based models [25]. Consumers with a heightened sense of environmental responsibility tend to show greater alignment between their intentions and actual behaviors related to green consumption [26].

Prior research identifies EA as a crucial psychological factor influencing consumers’ PBs in the context of green consumption [27]. As described earlier, PB includes economic, health-related, and psychological values derived from engaging in green consumption. Zammer and Yasmeen [28] noted that consumers with higher EA are better able to recognize the positive outcomes of green products, such as pollution reduction, energy conservation, and a healthier lifestyle. EA has been found to directly impact purchase intention, serving as a key mediating variable between environmental concern and green product knowledge. Similarly, Testa et al. [29] found that EA enhances perceptions of green product benefits and ultimately promotes pro-environmental behavior. They further argued that EA strengthens consumers’ belief in the long-term economic value of green products and motivates them to seek social recognition and moral satisfaction through green consumption [29,30].

Environmental awareness also helps mitigate the perceived sacrifices associated with green consumption. Specifically, higher awareness enhances consumers’ psychological resilience to barriers such as elevated prices, inconvenience, or limited availability, thereby facilitating sustainable purchasing decisions [31]. EA encourages consumers to internalize green consumption as a form of personal responsibility, prompting them to view such sacrifices as necessary investments in environmental preservation [19]. Within the same framework, Zhong and Chen [32] found that consumers with high EA are more willing to tolerate even unreasonable price premiums resulting from environmentally responsible practices by firms. In other words, consumers with high EA tend to exhibit lower sensitivity to PS in green consumption contexts [21].

Based on the literature above, this study posits that EA significantly influences both PB and PS in the context of green food consumption. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

EA has a positive effect on consumer PB.

H4.

EA has a negative effect on consumer PS.

2.3. Green Food Characteristics (GFCs)

GFCs refer to a range of product attributes and benefits that act as informational cues for consumers during purchasing decisions. These characteristics include both extrinsic elements (e.g., packaging, labeling, and pricing) and intrinsic qualities such as functionality, eco-friendliness, and health-related value [5]. Extrinsic attributes (e.g., visual appeal of packaging, eco-labels, and price) affect consumers’ sensory experience. In contrast, intrinsic attributes relate to the product’s core qualities, including nutritional value, safety, and health functions [1].

Extrinsic features can stimulate consumer interest and draw attention, thereby directly influencing purchase decisions. These elements are particularly effective in the short term, as they serve as rational cues during product evaluation [33]. However, although these attributes can enhance perceived value, they may also serve as vehicles for GW. As consumer concern about environmental and food safety issues grows, interest has shifted from extrinsic to intrinsic product features such as nutritional benefits, safety, and health outcomes [5]. As consumers grow more adept at discerning superficial packaging tactics, they focus increasingly on the product’s substance (i.e., ingredients, performance, and outcomes), making intrinsic attributes a more decisive factor in purchase behavior. Core attributes of green food strongly contribute to PBs linked to health, emotional fulfillment, and social value [34]. For example, green food’s ability to reduce exposure to harmful substances is especially appealing to environmentally conscious individuals [1]. Furthermore, the long-term economic value and ecological sustainability of green food are foundational elements that shape consumers’ favorable perceptions [30]. Other studies have suggested that the combined effect of intrinsic and supplementary green food features boosts PB, thereby reinforcing purchase intentions [35]. Specifically, green food’s eco-friendliness and health protection functions foster consumer expectations of economic, social, and moral value [24,36].

From a different perspective, GFCs also influence PS. When extrinsic attributes like clear information, fair pricing, and convenient access, are transparent and credible, they help reduce PS [37]. Owing to eco-friendly ingredients, sustainable production, and certification requirements, green food is generally priced higher than conventional alternatives [38]. These higher prices can be seen as economic burdens and may hinder purchasing. However, if consumers recognize green food’s environmental and health value, the perceived risks associated with these costs may become acceptable [1]. Limited distribution networks may also require consumers to sacrifice convenience in purchasing and consumption. Still, PS can be alleviated when consumers thoroughly understand and value the product’s characteristics [39]. Information asymmetry and low brand trust further increase consumer anxiety. In cases where information is inadequate or certification systems are unreliable, skepticism about a product’s eco-friendliness may arise. Nevertheless, transparent information and credible labeling can reduce this uncertainty and lower PS [40].

Based on these prior findings, this study identifies GFCs as critical factors influencing purchase intention and proposes the following hypotheses:

H5.

GFCs have a positive effect on consumer PB.

H6.

GFCs have a negative effect on consumer PS.

2.4. Consumer Characteristics (CCs)

Consumers with high levels of innovativeness tend to exhibit a stronger inclination to adopt new ideas, products, or brands, which is directly associated with the early adoption of eco-friendly products. In other words, innovative consumers are more responsive to emerging trends in sustainable consumption and show increased receptivity to green marketing for environmentally friendly products [41]. These consumers often engage in exploratory behavior, expressing curiosity about new brands and eco-labels, and may be motivated to make purchases based solely on keywords such as “green” or “eco-friendly”. Moreover, they are more likely to respond quickly and critically to environmental claims made by companies, which may lead to increased skepticism [42].

Another key trait is detail-orientation, referring to consumers who are highly meticulous in gathering and comparing information before making purchasing decisions. These individuals focus less on generalized brand messaging and more on specific, quantitative information about products, including raw materials, production methods, and distribution processes [43]. Such consumers are strongly aligned with trust-based decision-making and prioritize transparency and authenticity in green marketing [44].

Finally, consumer behavior is inevitably influenced by social trends. Trend alignment refers to the tendency of consumers to adapt their consumption behavior in line with socially dominant or mainstream values. Consumers attuned to widely accepted values such as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) focus, eco-friendliness, or veganism are likely to integrate environmental values into their personal identity or lifestyle [23]. In these cases, even when PB and risks are mixed or when green descriptors are potentially exaggerated, alignment with contemporary trends may still lead to purchase behavior. This reflects a psychological duality in which the appearance of trendiness can override critical evaluation [45]. Based on the above findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7.

CCs have a positive effect on PB in green food purchases.

H8.

CCs have a negative effect on PS in green food purchases.

2.5. PB

The concept of PB originates in economics and is widely used to highlight the positive relationship between the consumer and a product or service. There are three primary perspectives on how PB is defined. First, the benefit-based perspective defines PB as the consumer’s positive evaluation of a product’s attributes [46]. Second, some scholars interpret PB as a component of perceived value, focusing on the cognitive process through which consumers assess trade-offs between benefits and costs [7]. Third, in certain consumption contexts, PB is treated as synonymous with perceived value, with both concepts functioning interchangeably [47]. The present study adopts the benefit-based perspective, defining PB as a multidimensional and favorable evaluation formed by consumers when purchasing or using green products or services. In this framework, PB reflects the belief that the utility and environmental value of a green product represent meaningful benefits, thereby serving a central role in purchase decision-making [48].

As green food represents a major category within green products, the following hypothesis is proposed based on prior literature:

H9.

PB has a positive effect on GFPI.

Perceived value is a key determinant of green purchase intention, as it encapsulates consumers’ comprehensive evaluation of the benefits and worthiness of green products. However, the integrity of this perceived value can be compromised by external cues that cast doubt on the authenticity of environmental claims. A notable example is greenwashing, which refers to the practice of conveying a false or exaggerated impression of environmental responsibility [49].

When consumers are exposed to potential or suspected greenwashing, they tend to question the authenticity of green labels, eco-branding, or certifications, thereby weakening the trust foundation upon which perceived value is formed. This cognitive dissonance may dilute the perceived benefits or intensify perceived risks or sacrifices, ultimately reducing the positive impact of perceived value on green purchase intention [50]. Moreover, greenwashing introduces perceptual ambiguity that destabilizes consumers’ evaluations, particularly in contexts where regulatory oversight is weak or inconsistent [51,52]. As a result, greenwashing may function as a moderating factor, diminishing or even neutralizing the positive relationship between perceived value and green purchase intention.

2.6. PS

PS refers to the cost and risk consumers cognitively perceive in exchange for expected benefits when purchasing a product or service [53]. Purchase intentions are shaped by numerous factors, and consumers often interpret various types of costs (e.g., time, effort, and psychological discomfort while purchasing) as forms of sacrifice [54]. Hihaffar et al. [6] further defined PS as a multidimensional construct that includes quality uncertainty, financial cost, and the effort required to search for product-related information. PS is generally understood to have a negative effect on purchase intentions, especially in the context of green products, where consumers may experience more substantial PS compared with conventional alternatives.

Green products often undergo more rigorous environmental certification, follow stricter production standards, and contain higher-quality ingredients. Consequently, they are typically priced higher, and this premium is perceived as a financial burden. In addition, the level of transparency regarding product information affects consumers’ perception of quality uncertainty. For example, green food products often contain health-related ingredients labeled using technical terminology, which may be difficult for the average consumer to interpret. Although such products may support health and environmental goals, they may also involve taste-related trade-offs, deterring some consumers. Likewise, green products may be less convenient in terms of design and accessibility. Due to the need for heightened scrutiny of ingredients and supply chains, these products often require specialized packaging, non-mainstream distribution channels, and unconventional formats, all of which can reduce accessibility.

Moreover, using green products may create a social image that diverges from dominant consumer trends. Trend-sensitive individuals may associate green consumption with health and sustainability, but they also view it as incompatible with products perceived as fashionable, convenient, or high-performing. In this duality, green consumption may be a modernity or style PS. Drawing from these insights, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H10.

PS has a negative effect on GFPI.

2.7. GFPI

Green food is referred to globally by various terms, including “eco-food”, “natural food”, “health food”, and “organic food”. More importantly, it represents a multidimensional concept that encompasses environmentally friendly production, organic farming practices, sustainable distribution systems, eco-conscious packaging, and transparency in ingredient disclosure. As such, green food has become one of the most prominent domains of ethical consumption among modern consumers.

In China, green food is categorized into two levels: Grades AA and A. Grade AA products are subject to stricter standards for environmental impact, production methods, and health safety compared to Grade A. Specifically, AA-grade products are required to limit or eliminate the use of synthetic pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and veterinary drugs that could pose ecological or health risks. In contrast, A-grade products allow limited use of these substances within regulated thresholds. Additionally, the design of green food products in China must include specific mandatory elements such as the phrase “green food”, a green food logo, an anti-counterfeiting label, and a unique product identification number.

In this study, GFPI is considered to reflect a consumer’s willingness to purchase, recommend, and repurchase green food products.

2.8. GW

GW refers to the practice of exaggerating or misrepresenting environmental protection efforts to create a favorable image of environmental responsibility without implementing genuine improvements in environmental performance. Products promoted by such companies are often accompanied by misleading or overstated marketing claims, which can deceive consumers and stakeholders [55]. Although many firms incorporate sustainability into their marketing strategies, these claims often lack substantive eco-friendly or health-related outcomes. GW erodes consumer and stakeholder trust and negatively affects a firm’s long-term reputation and competitive position [56]. Zhang et al. [2] observed that when consumers detect GW, their expectations regarding product quality and satisfaction diminish, potentially leading to purchase avoidance or brand switching. Essentially, GW is more symbolic than substantive, reflecting a disconnect between a company’s surface-level environmental messaging and its actual sustainability performance. As a result, consumers may lose trust in environmental and health-related claims and ultimately engage in brand rejection or boycott behavior.

This study conceptualizes GW through three dimensions. The first is information discrepancy, referring to inconsistencies between a company’s eco-friendly messaging (e.g., advertisements and ESG reports) and its actual practices, ingredients, or environmental performance. This gap between symbolic and substantive actions, when perceived by consumers, can negatively influence purchase intention. The second is information ambiguity, which arises when environmental terms used by companies or products are vague and lack concrete evidence. This includes the deceptive use of general terms like “eco-friendly” or “sustainable” without verifiable actions, thereby misleading consumers through unsubstantiated claims. The third is perceived consumer confusion, a psychological reaction in which consumers feel uncertain or suspicious due to exaggerated or excessive green claims. Rooted in the concept of green skepticism, this dimension involves the overuse of complex or technical language without clear explanations, fostering doubt and confusion among consumers. These three dimensions are viewed as central to the GW construct and are believed to influence consumer purchase decisions for green products to varying degrees.

In this study, greenwashing is not treated as a direct antecedent of perceived value, but rather as a moderating variable that influences how perceived benefits and sacrifices affect purchase intention. This approach is grounded in the VAM framework, where perceived value is seen as a result of the trade-off between benefits and sacrifices.

Accordingly, this study proposes that these GW dimensions serve as moderating variables in the relationship between consumer perceptions and purchase intentions for green food. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H11.

GW moderates the relationship between PB and GFPI.

H12.

GW moderates the relationship between PS and GFPI.

We summarize the hypothesis and theoretical basis in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of hypothesis and theoretical rationale.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Model and Measurement Development

Since the early 2000s, global environmental concerns have increasingly shaped consumer behavior, leading to a sustained rise in interest in green food. Previous studies have commonly explained consumer purchase intentions using major theoretical models, including the technology acceptance model and the value-based adoption model (VAM). Given that green food is a product category in which purchase intentions are largely driven by perceived value, this study adopts the VAM framework to construct its research model. According to the VAM, consumers’ purchase decisions are typically shaped by a balance between PB and PS.

Recent research has shown that consumers weigh multiple dimensions of value when deciding whether to purchase green food. For example, Woo and Kim [1] found that consumers assess functional value, conditional value, social value, and emotional value, all of which significantly influence purchase intention. Similarly, Martey [57] noted that consumers face several barriers to purchasing green food, including high prices, skepticism about certification authenticity, and product unavailability. These challenges suggest that consumer decision-making in the green food domain is strongly value-based; hence, purchase intentions may decline when PS outweigh PB.

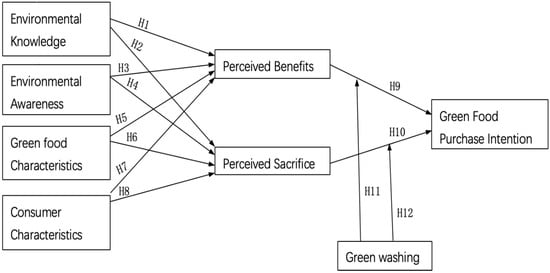

This study places particular emphasis on GW as a moderating variable that may disrupt the balance between PB and PS and ultimately affect final purchase decisions. Based on this rationale, the research model is proposed as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Green food purchase intention structural model.

Based on previous studies, we developed a set of measurement instruments aligned with the proposed model and modified the items to reflect the specific context of green food, which is the focal subject of this research. The measurement items used in this study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement items and sources.

3.2. Data Collection and Procedure

We conducted an online survey targeting Chinese consumers, who serve as the focal population for this study. The survey was administered in early December 2024 via Wenjuanxing, a professional online survey platform. The questionnaire consisted of two main sections. The first section included five items designed to collect demographic information, including gender, age, education level, occupation, and monthly income. The second section comprised a series of items developed to test the hypotheses derived from the proposed research model.

To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was reviewed by two researchers specializing in consumer behavior and one marketing expert. A pilot test was conducted with 50 participants to evaluate the reliability of the measurement instruments prior to full-scale data collection. All questionnaire items were measured using a five-point Likert scale.

A total of 400 responses were collected. After excluding incomplete or invalid responses, 347 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis. The data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 for descriptive statistics and SmartPLS for structural equation modeling (SEM). Partial least squares (PLS)-SEM was selected as the primary analytical tool due to its suitability for small sample sizes, non-normal data distributions, and its effectiveness in predicting latent variable models [66].

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of Respondents

Demographic analysis was conducted based on the 347 valid responses collected. First, the gender distribution indicated that 52.4% of respondents were male ( = 182) and 47.6% were female ( = 165), suggesting a relatively balanced gender composition. Second, the age distribution showed that participants were fairly evenly represented across age groups, with ~15% in each category. This suggests the sample captures a range of consumer perspectives across various life stages.

Third, the educational background revealed that more than 96.2% of respondents had completed at least a high school education, indicating sufficient cognitive capacity to understand and assess issues related to EA and green food consumption. Fourth, in terms of occupation, 54.2% of respondents were company employees, followed by students (24.2%), freelancers (8.4%), and public sector employees (7.2%). This distribution suggests that the majority of respondents are economically active and belong to consumer groups with purchasing power relevant to green food markets.

Finally, the income distribution revealed a concentration in the middle-to-upper income brackets, indicating that the sample is suitable for analyzing consumer sensitivity to green food pricing. Detailed demographic characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Respondent demographics.

4.2. Common Method Bias (CMB) Test

We assessed the potential for CMB in the collected data. Following the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. [3], we applied a method factor approach by introducing a method factor into the measurement model. We then compared the factor loadings for both the substantive factors and the method factor for each measurement item.

The results showed that all loadings on the substantive factors were greater than 0.67 and statistically significant. In contrast, the loadings on the method factor were mostly below ±0.1, indicating very weak associations. Although a few items (i.e., , , and ) were significant at the < 0.05 level, the effect sizes were minimal. The average variance explained (R2) by the method factor was just 0.0033, meaning only 0.3% of the total variance could be attributed to CMB.

Furthermore, the ratio of R12 (variance explained by substantive factors) to R22 (variance explained by the method factor) was approximately 196.4:1. This indicates that the explanatory power of the substantive constructs is more than 190 times greater than that of the method factor. In summary, the results suggest that the survey data are not significantly affected by CMB and that both the measurement and structural model results possess sufficient internal validity. The detailed results of the CMB analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

CMB test results.

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To assess the reliability and validity of the measurement model, we conducted a CFA. The results demonstrated that all factor loadings for the measurement items were equal to or greater than 0.689, indicating that the items effectively represented their respective latent constructs. These values met or exceeded the generally accepted threshold of 0.70, thereby confirming satisfactory indicator reliability.

Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs were above 0.738, and the composite reliability scores for all variables exceeded 0.85, demonstrating high internal consistency and confirming the measurement model’s reliability. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.581 to 0.731, all surpassing the recommended minimum threshold of 0.50. These results support the model’s convergent validity by indicating that each latent construct explains more than half of the variance in its observed indicators.

To further assess potential multicollinearity, we examined the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all measurement items. All VIF values were below 2.00, confirming that there were no multicollinearity concerns among the latent constructs.

Taken together, these findings confirm that the measurement model exhibits robust reliability and convergent validity and that each construct appropriately reflects its theoretical foundation, as supported by the prior literature. The detailed CFA results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analysis and model assessment results.

To assess discriminant validity among the latent constructs, we applied the Fornell–Larcker criterion [67]. Specifically, we compared the square root of the average variance extracted (√AVE) for each construct with the correlations between that construct and all other constructs. The results showed that for all constructs, where the √AVE values are located on the diagonal (bolded), they were greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlations in the same row and column. For example, the √AVE for was 0.765, which exceeds its highest correlation with any other construct (e.g., , = 0.300). A similar pattern was consistently observed across all constructs, including (√AVE = 0.783), (√AVE = 0.829), and (√AVE = 0.816).

These results indicate that each construct exhibits distinct and discriminable properties and that the measurement items reliably represent their theoretically defined constructs. That is, discriminant validity is confirmed, complementing the already established convergent validity. Therefore, the measurement model demonstrates sufficient construct distinctiveness and independence—an essential prerequisite for proceeding with the structural model analysis. Full results of the discriminant validity assessment are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Fornell–Larcker discriminant validity results.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

We analyzed the structural equation model using Smart-PLS 4.0, employing the PLS-SEM approach. To assess the statistical significance of the path coefficients, we applied a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples, using a one-tailed test at a significance level of = 0.05. These procedures followed the default settings in Smart-PLS [68] and hypotheses were tested based on the confidence intervals and p-values of the estimated path coefficients.

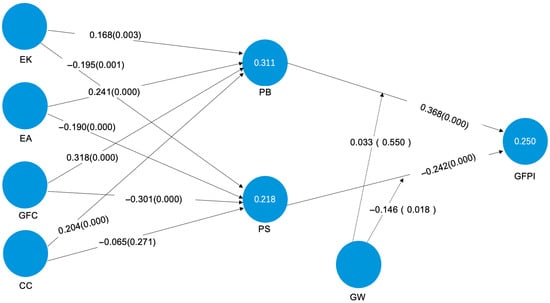

The results of the structural model analysis revealed that many of the proposed paths were statistically significant and the overall explanatory power of the model was relatively robust. Specifically, was significantly and positively influenced by ( = 0.168, = 0.003), ( = 0.241, < 0.001), and GFCs ( = 0.318, < 0.001), with an explanatory power of R2 = 0.311. This suggests that consumers’ internalization of eco-friendly knowledge and awareness, along with favorable evaluations of product characteristics, enhances their PB.

Meanwhile, was significantly and negatively influenced by ( = −0.195, = 0.001) and ( = −0.301, < 0.001). In contrast, had a positive effect on PB ( = 0.204, < 0.001), suggesting that heightened PB may entail greater cognitive burdens, such as time and effort for information search. did not have a statistically significant effect on ( = 0.271).

Further, had a significant positive effect on ( = 0.368, < 0.001), whereas had a significant negative effect ( = −0.242, < 0.001). These findings empirically confirm that both and function as direct determinants of , with an explanatory power of R2 = 0.250.

The results of the structural model visualization and path coefficient analysis are presented in Figure 2 and Table 7, respectively.

Figure 2.

Green food purchase intention structural model and path coefficients.

Table 7.

Hypothesis test results.

4.5. Moderation Analysis

Finally, we examined whether GW perception moderates the relationship between key independent variables and . Moderation analysis is used to statistically assess whether the strength of the relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable varies based on a third variable. In this study, interaction terms were created between the moderator () and the predictor variables ( and ), and these terms were integrated into the structural model. Following Smart-PLS’s default settings, we adopted the two-stage approach. The model was constructed by including the independent variables, the dependent variable, the moderator, and the interaction terms. We then ran the PLS algorithm to obtain the path coefficients and the explanatory power (R2).

To test the statistical significance of the moderation effects, we used bootstrapping with 5000 samples, applying a one-tailed test at a significance level of = 0.05. A significant moderation effect was considered to be present when the path coefficient for the interaction term was statistically significant. In addition, to aid interpretation, a simple slope analysis was conducted, plotting the interaction effects at the mean and at ±1 standard deviation levels of the moderator. This procedure allowed us to empirically evaluate the moderating role of GW perception in shaping consumers’ cognitive decision-making processes.

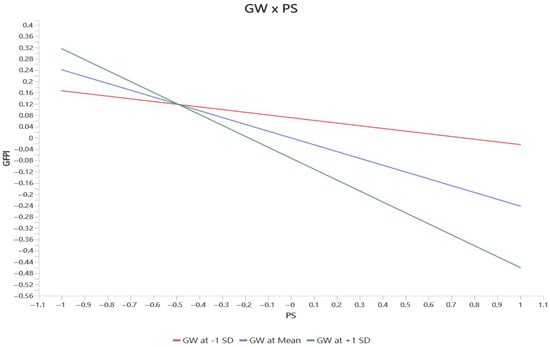

The results indicated that GW perception did not significantly moderate the relationship between and ( = 0.032, = 0.597, = 0.550). Therefore, H11 was rejected. This finding implies that even when consumers are skeptical of a company’s green claims, the positive effect of PB on purchase intention remains stable.

By contrast, H12 was supported, demonstrating a statistically significant moderation effect. Specifically, GW perception significantly and negatively moderated the relationship between and ( = −0.137, = 2.373, = 0.018). This result indicates that when GW perception is high, the negative impact of PS on purchase intention is amplified. In other words, consumers who strongly perceive GW are more sensitive to PS, leading to a sharper decline in purchase intention. This supports the existence of an amplifying moderation effect, suggesting that distrust in corporate green communication intensifies consumers’ cognitive resistance.

Accordingly, GW perception is confirmed to be a meaningful moderating variable. Detailed results of the moderation analysis are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Moderation analysis results—regulatory effects of greenwashing.

Figure 3 presents a visual representation of the interaction effect, illustrating how GW perception moderates the relationship between and . Overall, as increases, tends to decrease. However, the strength of this negative relationship varies considerably depending on the level of GW perception. When is high (+1 SD), the slope is steepest, indicating that consumers with strong perceptions of GW exhibit a sharply reduced purchase intention, even when experiencing the same level of PS. Conversely, when is low (−1 SD), the negative impact of on is substantially attenuated.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of GW on the relationship between PS and GFPI.

These results suggest that GW perception heightens consumers’ cognitive resistance by amplifying their PS sensitivity. In other words, the moderating role of GW functions as an amplifying effect, whereby skepticism toward green claims intensifies the negative influence of on .

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Academic Implication

This study structurally examines the influence of GW on consumers’ purchase intentions for green food, offering several academic contributions to the literature on green consumer behavior. First, it empirically extends the VAM by interpreting green consumers’ decision-making mechanisms through the dual lenses of PB and PS. Although previous VAM applications have primarily used the cost–benefit framework in digital technology adoption (e.g., mobile apps and cloud services; [69]), this study successfully applies the same theoretical foundation to the physical domain of environmental product consumption. Notably, it incorporates a structural relationship in which benefit-related factors (e.g., EK, EA, product attributes, and CCs) positively influence purchase intention, whereas sacrifice-related factors (e.g., price, quality uncertainty, and product accessibility) have negative effects.

Second, this study empirically demonstrates that GW perception functions not as a peripheral concern but as a substantive cognitive moderator within the consumer decision-making process. While previous studies have largely portrayed GW as unethical corporate communication [49,55], this research shows that GW moderates the relationship between PS and purchase intention. Specifically, the finding that GW amplifies the negative impact of PS—particularly under high PS—advances the literature on green skepticism [50] by providing structural model validation.

Third, this study contributes by focusing on Chinese consumers, who have been underrepresented in empirical research on green consumption. While most prior studies have emphasized Western markets [43,70], this study explores how Chinese consumers perceive and evaluate PB and PS within their own cultural and institutional context. In doing so, it expands the theoretical applicability of green consumption research to non-Western settings and provides a foundation for future studies targeting diverse consumer groups.

Fourth, this study integrates several variables previously examined in isolation—such as EK, EA, CCs, GFCs, and GW—into a comprehensive structural model. By analyzing how these variables influence purchase intention through PB and PS, it addresses the limitations of earlier studies that focused mainly on direct effects or basic mediation. This layered approach enhances both the theoretical coherence and empirical rigor of green consumer behavior research.

In summary, this study contributes to the advancement of green consumer behavior theory by (1) extending the application of VAM, (2) empirically validating GW as a moderating mechanism, (3) incorporating insights from Chinese consumer behavior, and (4) modeling complex causal pathways through structural analysis.

5.2. Practical Implications

Based on empirical findings from Chinese consumers, this study examined the cognitive factors influencing GFPI and the moderating role of GW perception. Several practical implications can be drawn, with a particular focus on strategies suited to China’s unique sociocultural and institutional context.

First, this study confirms that improving EK and EA is essential to promoting green consumption in China. Since 2020, China has identified “green transition” and “ecological civilization” as national strategic pillars and has promoted EA through various policies and education systems. However, actual consumer awareness remains uneven across regions and generations, with especially notable cognitive disparities among rural and low-income populations. Beyond national initiatives, local governments and companies should collaborate to deliver regionally tailored environmental education and provide experiential learning opportunities. Firms must go beyond abstract green claims and offer specific, easily understood examples and data. Additionally, given Chinese consumers’ high reliance on mobile platforms, tools such as WeChat Mini Programs and Xiaohongshu should be actively used for environmental marketing.

Second, PS remains a major barrier to green product adoption in China. Green products are generally more expensive than conventional alternatives and often face challenges related to quality uncertainty and user inconvenience (e.g., packaging, delivery, and limited access). Chinese consumers frequently emphasize the “cost-performance ratio”, suggesting that green products must demonstrate both environmental and practical value. Companies should seek to improve both the ecological and functional performance of their products while clearly communicating a value proposition that integrates health, environmental benefit, and cost efficiency. Creating green product sections on major platforms (e.g., Tmall and JD.com) and reinforcing eco-label credibility through partnerships with certification bodies will also be essential.

Third, this study confirms that GW perception significantly moderates the relationship between PS and purchase intention. In recent years, ESG and carbon neutrality discourse has grown rapidly in China, with many companies engaging in green branding. Simultaneously, consumer skepticism toward GW has increased. For instance, some major food brands have been criticized on social media for promoting “eco-friendly packaging” without substantive changes to their products or supply chains. This trend reflects a rising level of consumer literacy and highlights the growing reputational risks associated with superficial ESG claims. Companies must move beyond “green talk” to substantively demonstrate, verify, and transparently communicate their environmental commitments. In China, trust and transparency are emerging as foundational pillars of long-term brand success. Firms should consider deploying participatory certification systems or blockchain-based supply chain disclosures to reinforce credibility.

Fourth, at the policy level, there is a need to align with national initiatives such as the “Green Consumption Promotion Action Plan” and the “Dual Carbon Goals” (i.e., carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, respectively) by developing actionable and consumer-focused regulatory frameworks. To date, most policy efforts have focused on supply-side factors such as production technology and ESG metrics. This study shows that consumer-side cognitive variables (e.g., PS and GW response) also play critical roles in influencing behavior. Thus, central government agencies should enhance green food certification standards and streamline labeling systems, whereas local governments should provide financial and administrative support to help small businesses and agricultural producers meet certification requirements and address distribution challenges.

Furthermore, future studies could investigate how consumer perceptions of greenwashing influence firm-level outcomes such as sales performance, investor trust, or ESG-based capital access, thereby bridging the gap between consumer psychology and financial strategy.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

6.1. Conclusions

This study investigated how GW influences GFPI among Chinese consumers, with a focus on the mediating roles of PB and PS, and the moderating role of GW perception. Using the VAM and structural equation modeling, the findings revealed that EK, EA, and GFCs significantly enhance PB, while some of these factors simultaneously reduce PS. PB was positively associated with GFPI, while PS had a significant negative effect.

Most notably, this study confirmed that GW perception moderates the effect of PS on GFPI. Specifically, the negative relationship between PS and purchase intention is intensified among consumers who are more sensitive to greenwashing. This indicates that when consumers doubt the credibility of green marketing, they become more discouraged by perceived costs, such as high price or information ambiguity.

Theoretically, this research contributes to green consumer behavior literature by applying VAM logic to sustainable consumption, showing how PB and PS interact with trust-related signals to shape purchasing decisions. Practically, the findings emphasize the need for transparent and verifiable communication strategies to build consumer trust and reduce greenwashing-induced resistance. This is especially important in China’s evolving green economy, where environmental communication is becoming a strategic imperative for both businesses and policy actors.

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

While Wenjuanxing is a well-established survey platform in China and enables efficient access to targeted participants, it also introduces limitations in terms of sample representativeness. The respondent profile in this study is skewed toward educated, urban, and digitally active individuals, as reflected in the demographic statistics: over 96% of participants held a high school diploma or higher, and more than half were employed. This sample bias is relevant because previous research has shown that willingness to pay for eco-labeled food products in China is significantly influenced by consumers’ awareness and trust in labeling schemes—both of which are positively associated with higher education and media exposure. Therefore, although the current sample is appropriate for analyzing behavior among environmentally conscious urban consumers, it may not reflect the attitudes and perceptions of less-educated or rural populations. Future studies should aim to diversify sampling strategies to enhance external sampling.

As this study is based on cross-sectional survey data, the directionality of the relationships identified in the model should be interpreted with caution. While PLS-SEM allows for the testing of theoretically grounded pathways, it cannot establish causality due to the simultaneity of measurement. For example, it is conceivable that consumers who perceive high benefits from green food may seek out more environmental knowledge as a form of post hoc justification. Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs could more rigorously assess causality in these relationships.

Another limitation relates to the use of purchase intention rather than actual purchase behavior as the outcome variable. Prior research has extensively documented the “attitude–behavior gap” in sustainable consumption, wherein stated intentions fail to materialize into real-world actions due to price sensitivity, availability constraints, or social desirability bias. Future studies could address this limitation by incorporating behavioral data such as transaction records or in-store observations.

Additionally, this study does not directly explore the financial implications of greenwashing for firms. While the consumer side of GW is central here, recent research suggests that firms engaging in greenwashing face significant consequences, including increased capital costs, reputational risks, and declining investor confidence. Future research could bridge this gap by examining whether consumer distrust toward GW translates into tangible financial impacts, particularly under ESG-based investment frameworks.

Finally, this study uses purchase intention as the dependent variable, which may not fully capture actual consumer behavior due to the well-known attitude–behavior gap. Future research should seek to validate these findings through observed behavioral data or experimental purchase contexts.

Overall, future work should not only improve the causal rigor and behavioral validity of green consumption models but also link individual-level consumer psychology to firm-level strategic and economic outcomes. This would contribute to a more holistic understanding of sustainable markets in China and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z., R.J. and S.-D.P.; Methodology, D.Z. and R.J.; Software, D.Z.; Validation, R.J.; Formal analysis, D.Z.; Investigation, S.-D.P.; Data curation, D.Z. and R.J.; Writing—original draft, D.Z.; Writing—review & editing, S.-D.P.; Visualization, D.Z.; Supervision, S.-D.P.; Funding acquisition, S.-D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our study is a social science research based on an online survey targeting general consumers in China, with no collection of sensitive personal information, patient data, or images. According to the “Measures for Science and Technology Ethics Reviews” issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China in September 2023, ethical review is not required for this type of research. Specifically, Article 2 of the Measures states that: “For science and technology activities that involve human participants, including testing, surveys, and observations, and that collect personal information or biological data, ethics review is re-quired. Studies in social sciences that do not involve personal privacy, biological or medical intervention, or national security do not require ethics review”. The official Chinese government URL: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202310/content_6908045.htm (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Woo, E.; Kim, Y.G. Consumer Attitudes and Buying Behavior for Green Food Products: From the Aspect of Green Perceived Value (GPV). Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The Influence of Greenwashing Perception on Green Purchasing Intentions: The Mediating Role of Green Word-of-Mouth and Moderating Role of Green Concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøhlerengen, M.; Wiium, N. Environmental Attitudes, Behaviors, and Responsibility Perceptions Among Norwegian Youth: Associations with Positive Youth Development Indicators. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 844324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Tsui, P.-L.; Lan, B.-K.; Lee, C.-S.; Chiang, M.-C.; Tsai, M.-Y.; Lin, Y.-H. The Role of Perceived Value in Shaping Consumer Intentions: A Longitudinal Study on Green Agricultural Foods. Br. Food J. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Green … But at What Cost? A Typology and Scale Development of Perceived Green Costs. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 438, 140927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Yu, J.-R. Effect of Product Attribute Beliefs of Ready-to-Drink Coffee Beverages on Consumer-Perceived Value and Repurchase Intention. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2963–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental Knowledge and Conservation Behavior: Exploring Prevalence and Structure in a Representative Sample. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roczen, N.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bogner, F.X.; Wilson, M. A Competence Model for Environmental Education. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. Knowledge and Environmental Citizenship. In Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education. Environmental Discourses in Science Education; Sandoval-Hernández, A., Isac, M.M., Miranda, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kherazi, F.Z.; Sun, D.; Sohu, J.M.; Junejo, I.; Naveed, H.M.; Khan, A.; Shaikh, S.N. The Role of Environmental Knowledge, Policies and Regulations toward Water Resource Management: A Mediated-Moderation of Attitudes, Perception, and Sustainable Consumption Patterns. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 5719–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, J. Environmental Knowledge and Consumers’ Intentions to Visit Green Hotels: The Mediating Role of Consumption Values. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.L. Understanding Consumers’ Preferences for Green Hotels—The Roles of Perceived Green Benefits and Environmental Knowledge. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 1309–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, A.; Volz, U.; Rosmin, N.S. COVID-19 Highlights the Need to Strengthen Environmental Risk Management and Scale-Up Sustainable Finance and Investment Across Asia. IN-SPiRE 2020. Available online: https://www.inspiregreenfinance.org/publications/covid-19-lessons-for-sustainable-finance/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Appel, M. How and When Consumer Corporate Social Responsibility Knowledge Influences Green Purchase Behavior: A Moderated-Mediated Model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24680. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.S.; Bailey, R.A.; Hardt, N.; Allenby, G.M. Benefit-Based Conjoint Analysis. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 895–914. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Environmental Knowledge and Green Purchase Intention and Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Moral Obligation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Understanding Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Green Products in the Social Media Marketing Context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility and the Strategy to Boost the Airline’s Image and Customer Loyalty Intentions. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh Van Hoang, L.T.; Tung, L.T. Effect of Environmental Concern and Green Perceived Value on Young Customers’ Green Purchase Intention: The Mediating Roles of Attitude toward Green Products and Perceived Behavior Control. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubice Fac. Econ. Admin. 2024, 32, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M.J. A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Insights and Opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to Be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Factors Affecting Purchase Intention Towards Green Products: A Case Study of Young Consumers in Thailand. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2017, 7, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Akter, A. Perceived Environmental Responsibilities and Green Buying Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Attitude. Sustainability 2021, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of Consumer Environmental Responsibility on Green Consumption Behavior in China: The Role of Environmental Concern and Price Sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zameer, H.; Yasmeen, H. Green Innovation and Environmental Awareness Driven Green Purchase Intentions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Sarti, S.; Frey, M. Are Green Consumers Really Green? Exploring the Factors Behind the Actual Consumption of Organic Food Products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Nguyen, B.K. Young Consumers’ Green Purchase Behaviour in an Emerging Market. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 28, 674–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Wang, J. The Impact of Pro-Environmental Awareness Components on Green Consumption Behavior: The Moderation Effect of Consumer Perceived Cost, Policy Incentives, and Face Culture. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 965058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Chen, J. How Environmental Beliefs Affect Consumer Willingness to Pay for the Greenness Premium of Low-Carbon Agricultural Products in China: Theoretical Model and Survey-Based Evidence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curvelo, I.C.G.; Watanabe, E.A.D.M.; Alfinito, S. Purchase Intention of Organic Food Under the Influence of Attributes, Consumer Trust and Perceived Value. Rev. Gest. 2019, 26, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthasang, C.; Sinthusiri, N.; Chaisena, Y. Green Product and Green Perceived Value Effect on Purchase Intentions. WMS J. Manag. 2020, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of Organic Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review on Motives and Barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Soucie, K.; Alisat, S.; Curtin, D.; Pratt, M. Are Environmental Issues Moral Issues? Moral Identity in Relation to Protecting the Natural World. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-M. Decisional Factors Driving Organic Food Consumption: Generation of Consumer Purchase Intentions. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1066–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining Chinese Consumers’ Green Food Purchase Intentions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2019, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H. The Roles of Pollution Concerns and Environmental Knowledge in Making Green Food Choices: Evidence from Chinese Consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120561. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M.S. Linking Green Skepticism to Green Purchase Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Steenkamp, J.E.M. Exploratory Consumer Buying Behavior: Conceptualization and Measurement. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Fernández-Sabiote, E. Once Upon a Brand: Storytelling Practices by Spanish Brands. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2016, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray Shades of Green: Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, Myth, Farce or Prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y. Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Furniture: Do Health Consciousness and Environmental Concern Matter? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözer, E.G.; Civelek, M.E. The Effect of Perceived Benefit on Consumer-Based Brand Equity in Online Shopping Context. Ege Acad. Rev. 2018, 18, 711–725. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Geng, G.; Sun, P. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The Means and End of Greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, C. Towards Green Trust: The Influences of Green Perceived Quality, Green Perceived Risk, and Green Satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Gatti, L. Greenwashing Revisited: In Search of a Typology and Accusation-Based Definition Incorporating Legitimacy Strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.D. Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means–End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y. The Effect of Perceived Risk, Hedonic Value, and Self-Construal on Attitude toward Mobile SNS. Asia Mark. J. 2014, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrove, C.F.; Choi, P.; Cox, K.C. Consumer Perceptions of Green Marketing Claims: An Examination of the Relationships with Type of Claim and Corporate Credibility. Serv. Mark. Q. 2018, 39, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Park, J.; Chi, G. Consequences of “Greenwashing”: Consumers’ Reactions to Hotels’ Green Initiatives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1054–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martey, E.M. Purchasing Behavior of Green Food: Using Health Belief Model and Norm Activation Theory. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2025, 36, 562–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenis, N.D.; van Herpen, E.; van der Lans, I.A.; Ligthart, T.N.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Consumer Response to Packaging Design: The Role of Packaging Materials and Visual Design in Perceived Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, Y. How Can We Increase Pro-Environmental Behavior During COVID-19? An Investigation of the Effects of COVID-19 Concerns on Pro-Environmental Product Consumption. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 870630. [Google Scholar]

- Esfahani, M.S.; Reynolds, N. Impact of Consumer Innovativeness on Really New Product Adoption. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayande, P. Analyzing the Consumer Behavior for Effective New Product Launch. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckel, A.; Boeing, R. Relation between Consumer Innovativeness Behavior and Purchasing Adoption Process: A Study with Electronics Sold Online. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2017, 9, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Magnier, L.; Crié, D. Communicating Packaging Eco-Friendliness: An Exploration of Consumers’ Perceptions of Eco-Designed Packaging. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J. Consumer Reactions to Sustainable Packaging: The Interplay of Visual Appearance, Verbal Claim and Environmental Concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Pro-Environmental Purchase Behaviour: The Role of Consumers’ Biospheric Values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. On Comparing Results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five Perspectives and Five Recommendations. Mark. ZFP–J. Res. Manag. 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.W.; Chan, H.C.; Gupta, S. Value-Based Adoption of Mobile Internet: An Empirical Investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young Consumers’ Intention Towards Buying Green Products in a Developing Nation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).