1. Introduction

Sustainability reporting quality (SRQ) has emerged as a pivotal dimension of corporate governance and financial performance, reflecting firms’ commitment to transparent disclosure of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The significance of SRQ extends beyond ethical imperatives, serving as a strategic mechanism to enhance reputation, secure investment, and achieve competitive advantage in an increasingly interconnected global economy [

5,

6,

7]. Credible sustainability reporting equips stakeholders, including investors, regulators, and advocacy groups, with critical insights to assess corporate adherence to sustainable practices, fostering accountability and trust [

4,

8,

9]. Globally, the importance of SRQ has been reinforced by regulatory frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and sustainable development goals (SDGs), emphasizing alignment with international standards to address ESG concerns [

10,

11,

12].

Advanced economies, particularly in Europe and the United States, have established mandatory sustainability reporting regimes, underscoring the role of robust corporate governance in achieving SRQ [

13]. Meanwhile, emerging markets have adopted voluntary frameworks, with varying degrees of success in aligning SRQ with global standards [

14,

15]. Studies demonstrate that firms with effective governance structures—characterized by board independence, diversity, and expertise—are better positioned to produce high-quality sustainability reports, highlighting governance as a crucial determinant of SRQ [

16].

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries represent a compelling case for investigating SRQ, given its evolving corporate governance landscape and growing stakeholder pressures. Although the GCC countries’ Stock Exchanges promote voluntary sustainability disclosures, the absence of mandatory guidelines results in significant variability in SRQ across firms [

17]. International investors and local advocacy groups have driven firms to adopt ESG practices, yet the quality of disclosures remains inconsistent, often reflecting differences in governance practices and financial resources [

2,

18]. Notably, firms with well-structured boards—exhibiting diversity, independence, and expertise—tend to achieve higher SRQ, aligning their practices with international benchmarks [

19,

20].

Despite these insights, the existing literature on SRQ in GCC countries remains sparse, with limited empirical evidence on the interplay between corporate governance, financial performance, and SRQ. While studies have explored governance and financial factors independently, their combined effects, particularly the moderating role of governance in financially constrained environments, remain underexplored [

9,

11]. This gap is critical, as understanding how governance structures interact with financial performance to influence SRQ could inform policy and governance reforms tailored to the GCC countries context.

This research contributes to a significant gap in the literature by investigating how corporate governance, financial performance, and sustainability reporting quality (SRQ) interact in the specific context of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) nations. Although previous studies have analyzed these connections at a general level, empirical data from emerging economies, particularly the GCC, are scarce and dispersed [

2,

18]. Past research tends to target developed economies or address governance and financial performance separately, with little attention paid to the moderating effect of governance in financially constrained settings. This study builds on existing theoretical models by incorporating governance mechanisms as moderators that affect how financial performance is converted into SRQ, thereby moving agency and stakeholder theories one step forward in a resource-limited and culturally diverse context. By focusing on GCC companies, it considers institutional, regulatory, and cultural forces that distinguish this part of the world from international peers, providing detailed insights into the effectiveness of governance. Thus, this study makes both conceptual and empirical contributions by closing the regional gap and sharpening theoretical insights into the conditional influence of governance on sustainability reporting in emerging markets.

The aim of this study is to address significant gaps in the literature by inspecting SRQ between the companies listed in the GCC countries and investigating the effect of corporate governance. Based on agency and stakeholder principles, the research controls the size, freedom, diversity and specialization roles to shape SRQ, and to further explore the modeling effect of corporate administration on the relationship between financial performance and SRQ. This study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1. What is the level of sustainability reporting quality among companies in GCC countries?

RQ2: How does corporate governance in sustainability reporting affect the quality of GCC companies?

RQ3. What is the effect of corporate governance on sustainability reporting quality among firms in GCC countries?

RQ4. Does corporate governance moderate the relationship between financial performance and the sustainability reporting quality of GCC firms?

This study contributions to the SRQ literature are timely and important, especially when it comes to emerging economies such as those in the GCC, by exploring how corporate governance and financial performance shape SRQ in regulatory frameworks. By detecting both direct and modeling effects, this study contributes to the deep understanding of mutual activity between governance, economic performance and SRQ. Methodically, the study uses appropriate quantitative techniques in accordance with the research objectives, and the sample size is sufficient to support the strength of the analytical methods chosen. Theoretically, the study emphasizes the role of corporate governance in strengthening responsibility, expanding the agency theory, and that of stakeholders to enrich the principle of how companies react to the expectations of the growing ESG. Practically, conclusions provide valuable insights to decision-makers and regulators that require the development of stability frameworks that correspond to international standards, such as GRI and SDG. The study strengthens the strategic value of SRQ to increase the reliability of stakeholders and access to financial capital. Focusing on the GCC region, this research conducts basic tasks for future cross-composite and industrial-specific studies, which promotes a broad and better understanding of SRQ in emerging markets. The study eventually upholds SRQ as a cornerstone in efficient business administration and sustainable development.

This study is especially important as there is a rising need for more sustainable reporting worldwide, as shown by the 75% increase in ESG-related regulations in the past five years (Global Reporting Initiative, 2023 [

21]). On the other hand, only 30% of GCC countries and other emerging market companies disclose sustainability matters in full detail (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, 2022 [

22]). Research from 2023 also reveals that over half of investors consider how well sustainability reports are prepared to be a crucial element in their choosing of where to invest (Morgan Stanley, 2023 [

23]). This information points to a major issue with reporting, which means that it is vital to explore ways in which corporate governance and financial results can improve sustainability reporting. To address this gap, this study examines GCC firms, because their governments do not use consistent and regular enforcement of regulations.

The contribution of this study to the corporate governance and quality of sustainability reporting relationship is in line with the existing literature, which suggests that the results are replicable but not groundbreaking. Refs. [

17,

18,

24] have conducted similar research in the context of emerging markets, including the GCC, on governance mechanisms that determine SRQ. These studies highlight the influence of board characteristics on sustainability disclosures, thus supporting the conclusions of the current study. With regard to regulatory frameworks, GCC countries’ corporate governance codes tend to promote voluntary, as opposed to mandatory, sustainability reporting, resulting in firms having disparate SRQ levels [

17,

18]. The lack of binding disclosure requirements within GCC governance codes constrains the adoption of standardized SRQ, which the study could have described more explicitly to place its findings within regional governance practices and regulatory environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review.

Section 3 outlines the methods, followed by

Section 4, which presents the results and analysis, and which is followed by

Section 5, the discussion. Finally,

Section 6 highlights the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

Sustainability reporting quality (SRQ) has drawn increasing academic attention, especially in emerging markets where accountability and transparency are typically underdeveloped. Evidence shows that sustainability reporting across such nations is still sporadic, mainly because there are no compulsory guidelines for it and voluntary norms are used instead [

17,

18]. However, some companies embrace rudimentary reporting practices, and few adhere to high levels of disclosure involving external assurance from credible audit firms. Ref. [

3] pointed out that the application of Big Four assurance adds credibility but is rare in emerging markets.

In examining the impact of internal governance structures on SRQ, ref. [

25] showed that companies with larger boards are better positioned to adopt holistic ESG disclosure practices, because greater representation tends to yield diverse talent and oversight. In addition, ref. [

26] identify a significant correlation between board longevity and the level of depth in non-financial reporting among larger companies. The current study supports these findings by revealing that both board size and experience significantly enhance SRQ among GCC firms. By contrast, the influence of board gender diversity and independence is less consistent. Although [

27,

28] emphasize the importance of female representation in improving ESG transparency in U.S. and European firms, this effect appears weaker in GCC contexts. Structural and cultural constraints can hamper the impact of independent and female directors, as evidenced in research by [

29] in Sub-Saharan Africa. The second major aim of this study was to assess whether financial performance enhances SRQ. Empirical evidence across settings remains ambiguous.

Moreover, ref. [

6] established that financially successful SMEs in Africa would allocate more resources to ESG projects. Nonetheless, the current research finds that in the GCC, financial performance, as indicated by return on equity, does not have a significant impact on SRQ. This aligns with the research conducted by [

30,

31], who observed that in most emerging economies, companies tend not to translate profitability into sustainability investments unless they experience external pressure from stakeholders or regulators. Interestingly, the evidence indicates that, irrespective of profitability, larger companies have more powerful SRQ, perhaps because of considerations of reputation and the ability to bear extra reporting expenses. This finding is consistent with [

32], who find that firm size is still a powerful determinant of the depth and level of assurance of ESG disclosures. An increasing amount of empirical research emphasizes the vital role of corporate governance in determining SRQ. Empirical research across all these studies has reliably found that board attributes, such as size, independence, gender composition, and experience, have significant effects on the quality of sustainability disclosures. For instance, refs. [

25,

33] report that boards with more members and experience are likely to make better reports because they can exert more oversight and strategic advice.

The presence of female directors has also been linked to more inclusive reporting practices, owing to their diverse values and stakeholder-centric approaches [

27,

28]. The empirical evidence remains conflicting as far as the performance of independent directors is concerned, with some studies, for example, ref. [

34], pointing toward their limited effectiveness in emerging markets, where institutional and cultural challenges may limit their ability to supervise. This inconsistency indicates that, although corporate governance is a major determinant of SRQ, the latter’s influence can differ considerably based on the institutional environment and the intensity of regulatory enforcement. Financial performance is another core variable in the SRQ debate, but its role remains contested. On the one hand, financially stable companies are hypothesized to be able to invest in extensive reporting systems, thus yielding more credible and detailed sustainability disclosures [

5,

6]. Empirical evidence provided by researchers, such as [

3], has established positive correlations between financial metrics, such as return on equity and SRQ.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Agency theory, introduced by [

35], forms the cornerstone of modern corporate governance research, explaining the principal–agent conflict that arises from the separation of ownership and control in organizations. This conflict emerges because managers (agents), entrusted with operating the company on behalf of shareholders (principals), may act in their self-interest rather than maximizing shareholder value [

35]. To address this divergence, governance mechanisms such as independent boards, audit committees, and incentive-based compensation systems are implemented to align managerial actions with the objectives of the shareholders [

8,

36].

In the context of sustainability reporting, agency theory underscores the necessity of robust governance frameworks to mitigate opportunistic managerial behavior that prioritizes short-term gains over the long-term transparency demanded by stakeholders [

3,

12]. Sustainability disclosures, which do not directly impact immediate financial performance, are often deprioritized in favor of initiatives that enhance short-term profitability [

2]. This lack of managerial incentive to provide high-quality sustainability reports reflects a classic agency problem [

24,

33]. Studies have shown that governance mechanisms such as board independence and sustainability-focused committees serve as effective tools for reducing agency conflicts, thereby enhancing the transparency, comprehensiveness, and reliability of sustainability disclosures [

18,

37].

The theory further illuminates the dynamics between financial performance and sustainability reporting quality. Managers in financially constrained firms may opt to minimize sustainability disclosures to conserve resources for short-term operational needs [

5,

11]. However, governance mechanisms can act as mediators, ensuring that firms uphold their sustainability commitments regardless of financial constraints [

33,

38]. As firms with strong governance structures are more likely to balance short-term financial pressures with long-term sustainability goals, the relationship between governance and reporting quality is critical to this study’s investigation. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

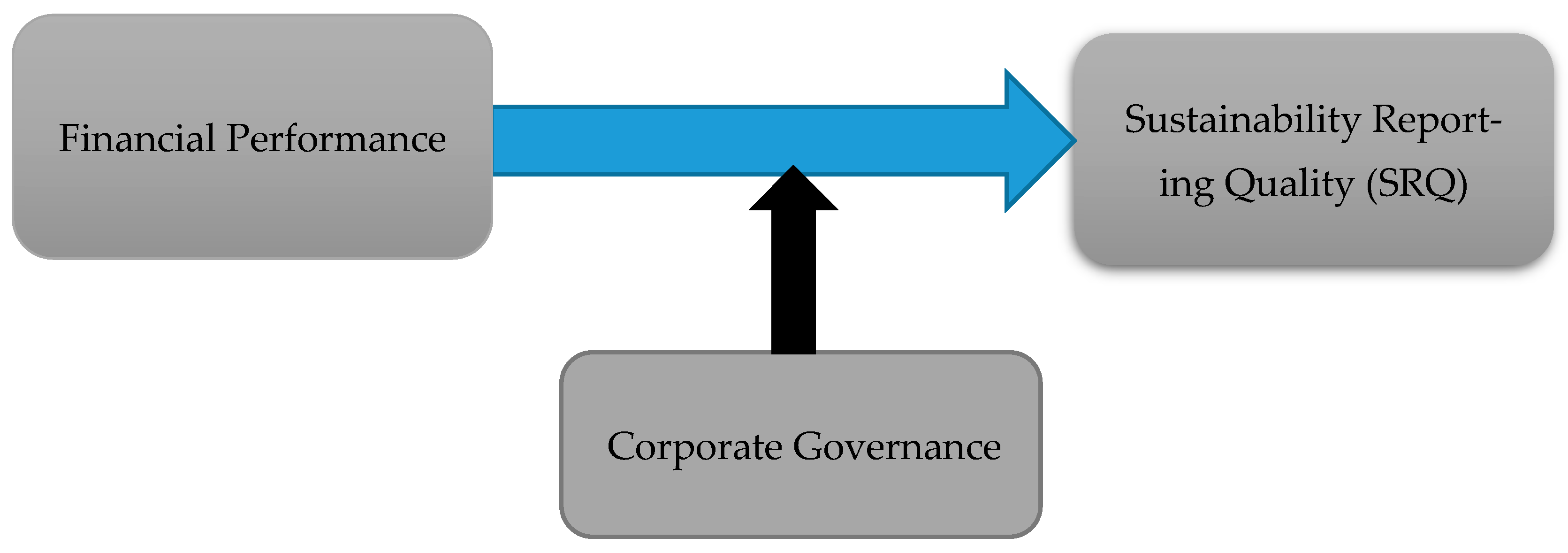

H1. Corporate governance positively affects SRQ.

Stakeholder theory, pioneered by [

39], challenges the traditional shareholder-centric view of corporate responsibility by advocating for the integration of diverse stakeholder interests into corporate strategies. This theory posits that firms are accountable not only to shareholders but also to a broad spectrum of stakeholders who influence and are influenced by the firm’s activities, including employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, and the wider community [

24,

39]. By emphasizing the moral and practical necessity of addressing stakeholder expectations, the theory establishes a foundation for examining sustainability reporting as a mechanism for stakeholder accountability [

6,

14].

High-quality sustainability reporting, as conceptualized under stakeholder theory, is characterized by its ability to provide comprehensive, transparent, and stakeholder-relevant disclosures [

11,

13]. Such reporting enables firms to demonstrate their commitment to ESG principles while addressing the informational needs of diverse stakeholder groups. Research has shown that firms with stronger financial performance are better equipped to meet these expectations, as they possess the resources necessary to invest in sustainability initiatives and develop high-quality disclosures [

5,

8].

Effective corporate governance structures are critical in ensuring that sustainability reports accurately reflect stakeholder interests. Boards with greater diversity and independence are more likely to integrate ESG considerations into corporate decision-making processes, thus enhancing the credibility and relevance of sustainability disclosures [

2,

20,

24,

33]. Moreover, firms that excel in aligning their governance frameworks with stakeholder expectations often experience increased reputational benefits, as stakeholders value transparency and accountability [

12,

38].

The theory also explains how financial performance influences sustainability reporting quality, as financially successful firms can allocate additional resources toward improving reporting mechanisms and adhering to global standards. By grounding this study in Stakeholder Theory, the role of financial performance in driving sustainability reporting quality is examined through the lens of stakeholder accountability. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. Financial performance has a positive effect on SRQ.

The moderating role of corporate governance in the relationship between financial performance and sustainability reporting quality underscores the importance of institutional structures in translating financial resources into transparent and credible disclosure. Corporate governance mechanisms, such as board independence, diversity, experience, and size, have been widely recognized for their role in improving sustainability practices and reporting [

40,

41]. For instance, independent boards ensure that decisions are free from managerial biases, thereby promoting transparency and accountability in sustainability reporting [

42,

43].

Board diversity, particularly in terms of gender and professional background, introduces a range of perspectives that enrich the decision-making process and enhance the firm’s ability to address stakeholder concerns [

20,

24,

33]. Research by [

3] and [

20] highlight the positive effects of board diversity on the comprehensiveness of sustainability reports, emphasizing the role of governance in shaping reporting quality. Similarly, larger boards, which often encompass a broader range of expertise, have been found to facilitate more thorough sustainability disclosures, although excessively large boards may lead to inefficiencies [

44].

The interplay between governance and financial performance has also been explored. Studies suggest that firms with strong financial performance and robust governance structures are better positioned to adopt stringent reporting standards, thereby enhancing sustainability transparency [

12,

30]. Conversely, weaker governance mechanisms may dilute the positive effects of financial performance on reporting quality because managers may prioritize financial outcomes over stakeholder accountability [

33,

38]. By analyzing governance as a moderator, this study seeks to uncover the conditions under which financial performance translates into high-quality sustainability reporting. This perspective acknowledges the nuanced, context-dependent role of governance mechanisms in fostering transparency and accountability. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3. Corporate governance positively moderates the relationship between financial performance and SRQ.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

To analyze the data, descriptive statistics provide initial insights into SRQ levels among the sampled firms. Ordered logistic regression was employed for hypothesis testing, given the ordinal nature of the dependent variable SRQ. This method enables the prediction of the probabilities of firms falling into each SRQ category, considering the ordered structure of the variable. The models capture the direct effects of financial performance and corporate governance on SRQ, as well as the moderating role of corporate governance in the financial performance–SRQ relationship.

Model diagnostics were conducted to validate the robustness of the findings. Tests for multicollinearity ensure that the independent variables are not excessively correlated, whereas the proportional odds assumption is verified to confirm the appropriateness of the ordered logistic regression. Model fit was evaluated using likelihood ratio tests and pseudo-R-squared values, and residual analyses were performed to identify potential specification issues. This comprehensive methodological approach ensures that the study’s findings are both reliable and generalizable, thus contributing valuable insights to the literature on sustainability reporting and governance practices.

Based on the results presented in

Table 3, the mean SRQ score was 1.687 on a scale from 0 to 4, indicating that most firms in GCC countries produce basic and limited sustainability reports. This relatively low mean suggests that, while some progress has been achieved, many firms have yet to adopt comprehensive sustainability reporting practices. The standard deviation of 1.172 reflects moderate variability, highlighting disparities in sustainability reporting among firms. A minimum score of 0 indicates that some firms do not engage in sustainability reporting, while a maximum score of 4 indicates that a few firms meet the highest reporting standards, including third-party assurance from a Big Four audit firm.

The corporate governance variables reveal significant insights into the governance structures of the sampled firms. Board size had a mean of nine members with a standard deviation of two, suggesting a moderate variation in board composition across firms. The range of 4 to 13 members underscores diversity in governance structures, with some firms having relatively small boards, while others maintain larger ones. Board gender diversity, measured by the number of female members, had a mean score of two, indicating relatively low female representation on corporate boards. A minimum value of 0 reveals the absence of female members in some firms, while a maximum value of three suggests that even firms with greater inclusivity exhibit constrained gender diversity. Board independence, measured by the number of non-executive members, had a mean of five, reflecting moderate independence standards. The range of two to seven non-executive members highlights variability, with some boards being less independent than others. Regarding board experience, the directors had an average tenure of seven years, indicating seasoned boards across the sample. However, the range of four to twelve years suggests that some boards have relatively less experienced members than their counterparts.

In terms of financial performance, represented by ROE, the results revealed considerable variability among firms. The mean ROE of 4.233% indicates modest profitability, but a wide range from −14.873% to 59.706% highlights substantial disparities in financial performance. Negative ROE values reflect that firms experienced significant losses during the sampled period, while others achieved substantial profitability. A standard deviation of 5.57% further illustrates variations in financial performance, which could influence firms’ capacity to invest in sustainability initiatives.

The analysis of the control variables further demonstrated diversity within the sample. The industry composition shows that 36.4% of the firms operated in the financial sector, while 63.6% belonged to non-financial sectors, reflecting a balanced representation of industries in the GCC economy. Firm size, measured by total assets, averaged US $8433 million, indicating substantial asset bases among the listed firms. However, the standard deviation of US $9263 million suggests significant disparities, with some firms managing smaller asset bases, while others control extensive resources. The range of US $5343 million to US $36,888 million underscores these differences in financial capacity. Additionally, firm age averaged 42.571 years, suggesting that the sample consisted predominantly of well-established firms. Nonetheless, the range of 7 to 126 years indicates a mix of relatively young and long-standing firms within the dataset.

4.2. Correlation Matrix

The study conducted a correlation analysis, shown in

Table 4, to evaluate associations between SRQ, corporate governance variables, financial performance, and control variables. This analysis also assessed potential multicollinearity among the independent variables. The highest correlation coefficient was 0.714, followed by 0.659 and 0.645, with most coefficients being below 0.50, indicating the absence of significant multicollinearity in the dataset.

The results revealed significant positive correlations between SRQ and several variables. Notably, board size had a strong positive correlation with SRQ (0.501,

p < 0.01), implying that larger boards, through diverse expertise and broader oversight, enhance sustainability reporting quality. Board experience showed one of the highest correlations with SRQ (0.607,

p < 0.01), emphasizing the role of experienced directors in fostering effective governance and robust reporting standards. Board gender diversity also positively correlated with SRQ (0.304,

p < 0.1), suggesting that increased female representation contributes to improved sustainability reporting, consistent with findings by [

14]. Board independence showed a weaker but significant positive correlation with SRQ (0.252,

p < 0.1), indicating that independent directors enhance accountability and transparency in sustainability practices.

The correlation between SRQ and financial performance ROE was weak and not statistically significant (0.129), suggesting that profitability alone does not directly influence sustainability reporting quality. Instead, governance structures and external pressures, such as regulatory and stakeholder demands, may play a more critical role, aligning with insights from [

50]. A modest but significant positive correlation between SRQ and firm size (lnTA) (0.263,

p < 0.1) highlights that larger firms, with greater resources and reputational incentives, tend to achieve higher sustainability reporting quality. Conversely, industry type showed a significant negative correlation with SRQ (−0.250,

p < 0.1), indicating that financial firms are less likely to produce high-quality sustainability reports compared to non-financial firms, possibly due to differing external pressures and priorities.

Interrelations among governance variables highlighted how these attributes collectively influence sustainability outcomes. Board size strongly correlated with board experience (0.714, p < 0.01 p < 0.01) and moderately with board gender diversity (0.645, p < 0.01 p < 0.01), suggesting that larger boards tend to include more experienced members and slightly higher female representation. Board independence also correlated significantly with board size (0.582, p < 0.01 p < 0.01), indicating that larger boards often include more non-executive directors.

Financial performance exhibited significant positive correlations with board independence (0.659, p < 0.01) and board gender diversity (0.435, p < 0.05), suggesting that governance structures characterized by independence and diversity can enhance financial outcomes. However, ROE negatively correlated with board experience (−0.141, p < 0.1), potentially reflecting a trade-off where experienced boards prioritize long-term sustainability over immediate financial returns.

Among the control variables, firm size (lnTA) positively correlated with SRQ (0.263, p < 0.1) and board experience (0.429, p < 0.05), suggesting that larger firms are more likely to have experienced boards and higher sustainability reporting quality. Interestingly, firm size negatively correlated with ROE (−0.221, p < 0.1), possibly reflecting economies of scale or differing strategic priorities among larger firms. These findings underscore the interconnected nature of governance, financial performance, and firm characteristics in shaping sustainability outcomes.

4.3. Panel GMM Regression Results

Table 5 presents the panel GMM regression results for the three models, including the moderating effect of corporate governance in the GCC region. The panel GMM approach has several advantages. Primarily, it addresses endogeneity concerns commonly encountered in ESG research, such as omitted variable bias, simultaneity, and measurement errors. By using lagged variables as instruments, this method ensures that the estimated relationship between SRQ and performance is unbiased and reliable. Additionally, as financial performance, governance, and ESG practices evolve over time, the panel GMM technique is well-suited for capturing dynamic effects. It effectively reflects the long-term impact of governance on SRQ and accounts for unobserved firm-specific factors, ensuring comprehensive integration of governance mechanisms within the analysis.

5. Discussion

5.1. SRG Levels

Table 6 presents the results addressing the first research question (RQ) regarding the level of sustainability reporting quality among GCC countries firms. The findings show that 17.27% of firms (152 out of 880) did not produce sustainability reports, reflecting limited integration of sustainability practices, likely due to weak regulatory enforcement, lack of awareness, or resource constraints [

11]. The largest category, comprising 29.09% of firms (256 observations), reported basic sustainability disclosures without governance mechanisms or external assurance. While this demonstrates progress, the absence of advanced structures like sustainability committees or third-party verification limits the credibility of these reports [

51].

Another 29.55% of firms (256 observations) have sustainability committees linked to their boards, indicating improved governance alignment with sustainability goals. However, the lack of external assurance at this level reflects ongoing challenges in achieving full transparency and accountability. Only 15.91% of firms (140 observations) used non-audit firms for assurance, raising concerns about the independence and rigor of the assurance process. At the highest reporting standard, just 8.18% of firms (72 observations) achieved an SRQ score of 4, reflecting assurance by Big Four audit firms. These firms are likely among the largest and most resourceful, driven by reputational or regulatory incentives.

Overall, the distribution of SRQ scores demonstrates progress but highlights significant room for improvement. Most firms remain at lower-to-moderate reporting levels (scores 0 to 2), indicating the need for robust governance mechanisms and external assurance. Uneven SRQ adoption likely stems from weak regulatory frameworks, limited stakeholder pressure, and varying resource availability. Firms in highly regulated or scrutinized industries tend to adopt higher standards, whereas those in less-regulated sectors lag behind. These findings align with studies such as [

24], which emphasize the underdevelopment of SRQ in emerging economies due to weak regulations, and [

18], which identified similar challenges in Nigeria [

28]. The US health care system reveals a strong positive relationship between the gender range through the representation and diversity indices and through stability reporting quality, even when checking for company and management variables. After completing it, research on Greece confirms that corporate administration and CSR functions are quite correlated with financial performance measurements, such as total assets, EBITDA and stock exchange listing, which emphasizes the interaction between economic and non-economic disclosures [

26]. In addition, a systematic review of subsequent studies of the non-financial reporting quality (NFRQ) identified, in the case of the EU, the size of the company, the quality of management and the performance of stability as the most important drivers of NFRQ [

52]. However, the findings by [

29] in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) suggest that although institutional ownership does not directly affect social stability reporting, it controls the effect of freedom and gender diversity in the board committee, and reflects the importance of the internal disciplinary regime in the company. In Turkey’s [

31] assistance of 50 index companies, management functions such as functional time, size and external whiteboard evaluation were positively associated with general stability, and environmental and social performance. Meanwhile the low prevalence of Big Four assurance diverges from [

3], who linked global audit networks to improved reporting quality in developed markets. Ref. [

53] evaluated CSR impact in 76 studies between developed and developing economies, and found that pole press (regulator, investors) form CSR in developed countries, and companies in developing countries affect international stakeholders, and the domestic public with relatively low pressure. Ref. [

54] also endorsed that the effectiveness of SRQ is strongly influenced by CG structures, fixed properties and financial results. Governance mechanisms, such as board diversity, freedom and experience, are important for promoting stability practices and improving the quality of non-financial disclosures. US health care firms suggests that gender variation with high boards—by changing through the relationship between female directors and variation indexes—is associated with quality disclosure quality [

27]. From a developing country perspective, studies of the BIST 50 Index in Turkey reveal that board tenure and size significantly affect sustainability performance, while excessive director attendance at board meetings may have a detrimental effect on social performance. Larger firms’ SRQ typically demonstrate higher levels of sustainability disclosure due to increased public scrutiny and resource availability [

32]. Likewise, ref. [

32] found that listed Greek companies with higher total assets exhibited stronger ESG practices and reporting, further supported by the positive correlation between CSR and financial metrics like EBITDA and stock exchange listing.

Overall, these research outcomes are vital to business administration, especially as they relate to diverse, experienced and well-structured boards serving as a catalyst to increase SRQ. The difference between governance and financial results is especially important in emerging markets, where the regulatory environment is often fragmented and institutional pressure is different. The purpose of this study is to contribute to the growing literature mass by testing these conditions in the form of an emerging market, which provides practical insight to business leaders and policymakers.

5.1.1. Corporate Governance and SRQ

The findings in

Table 7 provide critical insights into the influence of corporate governance mechanisms on SRQ among listed firms in GCC countries, as analyzed using ordered logistic regression. The results reveal that board size is a significant positive predictor of SRQ (

p = 0.035), suggesting that larger boards enhance sustainability reporting practices. Larger boards bring diverse expertise and perspectives, improving decision-making and oversight on sustainability matters. This is consistent with agency theory, which posits that larger boards serve as an effective mechanism to align managerial actions with stakeholder interests, thus enhancing accountability in ESG disclosures. This result aligns with prior findings by [

33,

55], who observed that larger boards foster better governance and stakeholder representation, leading to improved SRQ.

Board experience also emerged as a significant driver of SRQ (

p = 0.001), underscoring the role of experienced directors in promoting high-quality sustainability reporting. Experienced board members possess an in-depth understanding of reporting standards, sustainability frameworks, and stakeholder expectations, enabling firms to adopt best practices and align reporting with stakeholder interests. This finding supports agency theory by highlighting the role of expertise in mitigating information asymmetry and ensuring management accountability. It also resonates with the evidence provided by [

25], who observed a positive link between experienced boards and improved governance practices, including SRQ.

Contrary to expectations, board gender diversity and board independence were not statistically significant predictors of SRQ (

p > 0.05). While gender diversity and independence are often linked to improved governance outcomes [

8,

56], their lack of significance in this context may reflect cultural or institutional barriers within GCC countries firms. Agency theory suggests that while these mechanisms are intended to enhance accountability and transparency, their effectiveness may be limited without sufficient regulatory support or societal emphasis. For instance, the influence of female directors may be constrained by organizational and cultural dynamics, as noted by [

57]. Similarly, the insignificant role of board independence suggests that GCC countries firms may rely more on executive directors’ operational expertise rather than non-executive directors to drive sustainability, diverging from findings in other contexts, such as [

34].

Among the control variables, firm size (p = 0.001) was a strong determinant of SRQ, indicating that larger firms tend to produce higher-quality sustainability reports. This aligns with agency theory, as larger firms face greater scrutiny from stakeholders and have more resources to invest in comprehensive reporting. This finding corroborates prior studies that highlight the influence of firm size on SRQ through resource availability and reputational concerns. Conversely, industry type showed a significant negative association with SRQ (p < 0.001) for financial firms, suggesting that they are less likely to engage in high-quality sustainability reporting compared to non-financial firms. This could reflect differences in regulatory pressures or the perceived relevance of sustainability issues within the financial sector. Interestingly, firm age did not significantly influence SRQ (p > 0.05), implying that maturity alone does not guarantee improved reporting practices, further emphasizing the importance of governance structures.

The findings reinforce the relevance of agency theory in understanding the relationship between corporate governance and SRQ. Agency theory posits that corporate governance mechanisms, such as board oversight and accountability, are critical for mitigating agency problems and aligning management actions with stakeholders’ interests. The significant positive effects of board size and experience on SRQ support the theory’s premise that robust governance structures enhance transparency and accountability, thereby improving sustainability reporting. Additionally, stakeholder theory complements these findings by emphasizing that corporate governance plays a vital role in addressing the expectations of diverse stakeholders, such as investors, regulators, and the public, who demand reliable and transparent sustainability disclosures.

5.1.2. Financial Performance and SRQ

The results in

Table 8 addressing the third research question provide valuable insights into the determinants of SRQ among GCC countries firms, particularly the role of financial performance, firm size, industry type, and firm age. Return on equity (ROE), the primary metric for financial performance, exhibited a positive coefficient (0.009) but was not statistically significant (

p = 0.747). This suggests that profitability does not significantly drive SRQ in GCC countries. Instead, SRQ appears to be influenced more by external pressures, such as stakeholder expectations and reputational concerns, than by financial outcomes. This aligns with stakeholder theory, which posits that firms prioritize sustainability practices in response to demands from stakeholders, including investors, regulators, and the public, rather than financial performance alone [

34].

In contrast, firm size (lnTA) emerged as a significant predictor of SRQ, with a strong positive coefficient (1.473,

p < 0.001). Larger firms are more likely to produce high-quality sustainability reports, likely due to their greater visibility and capacity to allocate resources to sustainability initiatives. According to stakeholder theory, larger firms face heightened scrutiny from stakeholders, incentivizing them to adopt robust and transparent reporting practices. Additionally, their resource capacity allows them to invest in advanced reporting frameworks and sustainability initiatives, reinforcing their ability to meet stakeholder expectations. This finding aligns with prior studies by [

18,

56], which also found a positive correlation between firm size and SRQ in emerging markets.

The analysis revealed that industry type had a significant negative effect on SRQ, with financial firms showing lower SRQ compared to non-financial firms (−2.253,

p < 0.001). This may reflect the unique dynamics of the financial sector, where sustainability concerns are often perceived as less material than in industries, such as manufacturing or energy, which face stronger external pressures to demonstrate sustainability practices [

33]. Stakeholder theory supports this view by highlighting the role of external pressures in shaping corporate behavior, as firms in environmentally impactful industries are more likely to adopt high-quality sustainability reporting to meet stakeholder expectations. The findings underscore the need for industry-specific strategies to improve SRQ, particularly in sectors where sustainability practices may not be a primary focus.

Firm age did not have a significant effect on SRQ (0.002,

p = 0.746), suggesting that longevity does not necessarily translate into better sustainability reporting. While older firms may benefit from institutional knowledge and established processes, these advantages do not directly lead to higher SRQ. This finding emphasizes the importance of governance structures, regulatory compliance, and stakeholder pressures over historical longevity in driving sustainability practices. These results challenge earlier findings by [

16], who suggested that older firms might have higher SRQ due to their accumulated experience and institutional frameworks.

The non-significance of ROE aligns with the findings of [

36], who argued that profitability metrics alone do not translate into better sustainability practices, especially in contexts where external pressures play a more critical role. The modest positive relationship between ROE and SRQ suggests that financial performance may still enable firms to allocate resources toward sustainability initiatives, but this effect was not pronounced in the GCC countries context. Stakeholder theory provides a framework for interpreting this result, as it suggests that firms engage in sustainability reporting to meet stakeholder demands rather than as a function of profitability. This indicates that governance structures, industry dynamics, and regulatory pressures play more pivotal roles than financial outcomes.

The significant relationship between firm size and SRQ reinforces stakeholder theory, as larger firms are subject to greater stakeholder scrutiny and expectations. These firms likely view sustainability reporting as a strategic tool to build trust, enhance legitimacy, and manage reputational risks among their stakeholders. Conversely, the absence of significant effects for ROE and firm age suggests that SRQ is not inherently tied to financial outcomes or institutional longevity but is driven by external pressures and the ability to meet stakeholder demands.

5.1.3. Corporate Governance, Financial Performance and SRQ

The findings in

Table 9 answer the last research question by providing valuable insights into the moderating role of corporate governance in the relationship between financial performance and SRQ among GCC countries firms. The results reveal that higher financial performance is positively and significantly associated with improved SRQ (coefficient = 0.283,

p = 0.011), supporting the notion that financially successful firms possess the resources and strategic flexibility to invest in comprehensive sustainability reporting. This aligns with the view that profitability enables firms to allocate financial resources toward stakeholder-centric initiatives, including sustainability disclosures [

2].

Corporate governance variables, particularly board size and board experience, play significant moderating roles in strengthening the positive relationship between ROE and SRQ. The interaction between board size and ROE (coefficient = 0.339, p = 0.013) indicates that larger boards enhance the capacity of financially successful firms to achieve better SRQ. This finding highlights the role of diverse expertise and increased oversight that larger boards bring, which aligns with stakeholder theory by ensuring that firms prioritize broader stakeholder needs through robust reporting practices. Similarly, the significant interaction of board experience with ROE (coefficient = 0.324, p = 0.006) underscores the importance of experienced directors in leveraging financial performance to improve SRQ. Seasoned board members are better equipped to align financial goals with sustainability imperatives, ensuring that corporate strategies integrate long-term accountability and stakeholder engagement.

However, the interaction effects of board gender diversity and board independence with ROE were insignificant, suggesting that these governance attributes do not substantially influence the extent to which financial performance impacts SRQ. This outcome deviates from findings in other contexts, such as those of [

54,

57], which highlighted the significance of gender-diverse and independent boards in driving sustainability outcomes. The insignificance of gender diversity in the GCC countries context may stem from structural limitations, where independent directors and female board members may lack sufficient influence over financial strategies or sustainability practices. This highlights the need for stronger empowerment mechanisms to enhance the effectiveness of these governance attributes in advancing sustainability goals.

The direct effects of governance variables on SRQ further emphasize their importance. Board size (coefficients = 0.241, p = 0.035) and board experience (coefficients = 0.472, p = 0.001) were both positively and significantly associated with SRQ, reaffirming their individual contributions to improving reporting quality. These findings align with agency theory, which posits that robust governance structures enhance accountability and ensure that managerial decisions reflect the interests of shareholders and stakeholders alike. Larger and more experienced boards provide the oversight and expertise necessary to promote transparency and ensure high-quality sustainability disclosures.

Control variables also played significant roles in shaping SRQ. Firm size (lnTA) was positively and significantly associated with SRQ (coefficient = 0.893, p < 0.001), indicating that larger firms are better positioned to produce high-quality sustainability reports due to their greater resources and heightened visibility to stakeholders. Conversely, the negative relationship between industry type and SRQ (coefficient = −1.650, p < 0.001) highlights that financial firms are less likely to prioritize sustainability reporting compared to non-financial firms, possibly due to differing external pressures and stakeholder expectations.

5.2. Robustness of Results

Several checks were conducted to validate the stability of the results across alternative specifications, datasets, and methodological approaches. Firstly, the dependent variable, SRQ, was redefined using alternative scoring criteria to assess the consistency of the findings. Additionally, financial performance, initially measured through ROE, was substituted with alternative metrics such as Return on Assets (ROA) and Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT). This allowed for testing the generalizability of the observed relationships under varying definitions of financial performance.

Endogeneity concerns, particularly with corporate governance variables, were addressed using IV techniques. Relevant instruments were identified based on theoretical and statistical justifications, ensuring that the relationships between the variables were not driven by reverse causality or omitted variable bias. Subsample analyses were conducted by segmenting the data into financial and non-financial firms, as well as firm size, to evaluate whether the results were consistent across these subgroups. This approach provides insights into industry- and size-specific dynamics that could potentially influence the quality of sustainability reporting.

Table 10 presents the panel GMM regression results for the three models employed to examine the relationship between SRQ and company performance, incorporating the moderating effect of corporate governance. Various proxies were used to test the robustness of the findings.

The table employs alternative measures for the key variables to assess the robustness of the findings and to minimize the risk of bias from specific operational definitions. Return on equity (ROE) is used as a reliable indicator of firm performance, offering a holistic view of financial outcomes. Board independence, captured by the number of independent directors, serves as a refined proxy for corporate governance. Firm size was measured using the natural logarithm of market capitalization, a standard approach that mitigates data skewness and facilitates comparability. In addition, company growth is assessed through changes in total assets, representing a practical measure of long-term development. These alternative specifications enhance the robustness of the study and reinforce the consistency and reliability of the results across different model settings. Consequently, the key findings remain valid and statistically significant when the panel GMM regression method is applied.

In addition, alternative modeling techniques have been employed. Beyond the primary ordered logistic regression model, linear regression with robust standard errors and generalized ordered logit models were used. These methods confirmed that the findings were not sensitive to the choice of estimation technique. Additionally, fixed-effects models were applied to account for unobserved firm-level heterogeneity, ensuring that the relationships observed were attributable to the variables of interest rather than to time-invariant firm-specific factors.

Time-lagged effects were also tested by lagging the independent variables by one period to determine whether prior financial performance and governance attributes influenced the subsequent SRQ. This temporal adjustment enhanced the causal interpretation of the findings. Multicollinearity was assessed using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) scores, with all variables falling within acceptable thresholds, confirming that the regression results were not distorted by multicollinearity. Outlier and leverage diagnostics were conducted to identify the influential data points. Robust regression techniques were then applied to ensure that the results are not driven by extreme or high-leverage observations.

These extensive robustness checks collectively reinforce the validity of the study’s findings and their applicability to firms listed in GCC countries. While detailed results of these checks are not presented here owing to space limitations, they are available upon request. This approach aligns with established practices in the field and enhances the transparency and credibility of research conclusions.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of sustainability reporting quality (SRQ) among listed firms in an emerging market, focusing on the interplay between corporate governance, financial performance, and firm characteristics. The findings therein underscore the critical role of governance mechanisms, particularly board size and experience, in enhancing SRQ. Larger boards with diverse expertise and experienced directors were found to contribute significantly to higher-quality sustainability disclosures. This suggests that broader expertise and deeper strategic insights enable boards to better oversee and prioritize ESG transparency. The findings reveal that, while there has been progress in sustainability reporting, many firms still produce basic or limited reports. Most companies demonstrate SRQ characteristics at the lower-to-moderate end of the scale, thus demonstrating the necessity of improved governance systems and enhanced transparency. A positive relationship exists between corporate governance elements such as board size, board experience, and SRQ. When boards contain a larger number of directors, they can effectively supervise sustainability matters, and directors with extensive experience help organizations better follow sustainability reporting requirements. The research results support agency theory because properly managed firms tend to match their operational methods with stakeholder expectations. By contrast, the roles of board independence and gender diversity were less pronounced, suggesting potential contextual limitations in their influence within the corporate environment. This lack of a relationship emerged because of the institutional and cultural barriers that exist in GCC countries. Empirical evidence indicates that firms with greater non-executive board oversight are more likely to produce comprehensive corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosures. Similarly, board experience has been shown to significantly enhance sustainability reporting quality (SRQ). Board gender diversity also emerges as a critical moderating factor. Gender-diverse boards are better equipped to incorporate a wider range of stakeholder concerns and ethical considerations, thereby strengthening the link between financial performance and the quality of sustainability disclosures [

56,

57].

Financial performance, as measured by ROE, was not directly associated with SRQ, indicating that profitability alone may not drive sustainability reporting practices in the absence of external pressure or governance support. However, the moderating effect of corporate governance, particularly through board size and experience, reveals that firms with stronger governance structures are better positioned to translate financial performance into enhanced SRQ. This highlights the interconnected nature of financial resources and governance quality in terms of advancing sustainability reporting.

Firm size has emerged as a consistent and significant determinant of SRQ, with larger firms producing more comprehensive and credible reports. This finding reflects the greater resource availability, reputational incentives, and stakeholder scrutiny faced by larger organizations. Industry type also played a significant role, with financial firms reporting lower SRQ levels than non-financial firms, likely due to differing external pressures and regulatory expectations across sectors. Industries with high environmental and social impact, such as oil, gas, and construction, are subject to intensified external pressures to disclose environmental, social, and governance (ESG) information. These pressures intersect with board governance dynamics, influencing the extent and quality of sustainability disclosures. Within the institutional and cultural framework of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region, the effectiveness of ESG reporting is shaped by ongoing governance reforms and prevailing corporate norms. The progress of ESG disclosure practices varies across Gulf countries, with firms in Saudi Arabia—driven by Vision 2030 initiatives—and the United Arab Emirates demonstrating notable advancements, while companies in less regulated environments continue to lag behind.

This study’s findings provide robust empirical evidence on the determinants of SRQ in emerging markets, offering insights into the importance of governance structures and firm characteristics in shaping sustainability reporting practices. By highlighting the moderating role of corporate governance in the financial performance–SRQ relationship, this study contributes to a broader understanding of how firms in emerging markets can enhance their sustainability reporting quality in response to evolving stakeholder demands and global standards.

The findings of this study have significant theoretical and practical implications, particularly for advancing SRQ in emerging economies like GCC countries. Theoretically, the study makes a notable contribution to the intersection of agency theory and stakeholder theory by demonstrating how corporate governance and financial performance collectively influence SRQ. Agency theory posits that effective governance structures mitigate agency problems by enhancing transparency and aligning management actions with the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders. This study supports this premise by showing that larger boards and experienced directors are associated with higher SRQ, underscoring the role of governance in fostering accountability. Moreover, the findings extend stakeholder theory by illustrating how firms respond to diverse stakeholder pressures—such as investor expectations, regulatory requirements, and societal demands—to improve sustainability reporting. The study demonstrates that governance mechanisms, such as board expertise, amplify firms’ capacity to meet stakeholder expectations, particularly in contexts where regulatory enforcement is limited.

The results also address a critical gap in the literature by highlighting the moderating role of corporate governance in the relationship between financial performance and SRQ. This finding provides a nuanced understanding of how governance attributes, such as board size and experience, enhance the translation of financial resources into sustainability outcomes. By integrating these insights, the study enriches theoretical frameworks that seek to explain the dynamics of sustainability practices in resource-constrained environments, offering new perspectives on how governance structures shape reporting quality in emerging markets.

From a practical standpoint, this study provides actionable insights for corporate leaders, policymakers, and regulators seeking to improve SRQ. The findings emphasize the importance of robust governance structures, particularly in ensuring that firms adopt comprehensive and credible sustainability reporting practices. For corporate leaders, the study highlights the value of enhancing board composition by incorporating experienced directors and increasing board size to strengthen oversight and decision-making on sustainability matters. Firms are encouraged to establish dedicated sustainability committees and collaborate with reputable audit firms to provide third-party assurance, thereby enhancing the credibility and transparency of their disclosures.

For policymakers and regulators, the study underscores the need for regulatory frameworks that incentivize or mandate sustainability reporting. These frameworks should promote uniformity and alignment with international standards, such as the GRI and the SDGs. By introducing policies that prioritize SRQ, regulators can encourage firms to adopt transparent reporting practices, fostering stakeholder trust and attracting responsible investment. Additionally, the study highlights the need for industry-specific strategies to address sectoral differences in sustainability reporting, particularly for financial firms, which tend to lag in SRQ compared to non-financial firms.

Overall, this study provides a foundation for informed decision-making by stakeholders aiming to enhance SRQ in GCC countries and similar emerging markets. It offers a roadmap for integrating governance and financial strategies to achieve sustainable business practices, contributing to broader objectives of accountability, transparency, and sustainable development.

This study provides valuable insights into the relationship between corporate governance, financial performance, and SRQ among firms in GCC countries. However, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, reliance on secondary data from annual reports may not fully capture the nuances of sustainability reporting practices, as firms may present incomplete, inconsistent, or overly optimistic disclosures. The study’s focus on quantitative data further limits the exploration of qualitative dimensions, such as the motivations or challenges firms face in adopting sustainability reporting. Additionally, the study does not account for industry-specific factors beyond general classifications (e.g., financial vs. non-financial), which may mask the unique dynamics affecting SRQ within particular sectors. The sample is limited to 88 listed firms in premier markets over a 10-year period, and, while comprehensive, it excludes smaller and unlisted firms, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to the broader corporate landscape of GCC countries. Finally, the study’s geographic focus on GCC countries may restrict its applicability to other emerging markets in different regulatory, cultural, and economic contexts.

Future research should address these limitations by adopting a mixed-method approach that integrates qualitative insights, such as interviews with board members or sustainability officers, to explore the contextual drivers of sustainability reporting practices. Expanding the scope to include a broader range of firms, such as small and medium enterprises (SMEs), would provide a more comprehensive understanding of SRQ across different organizational sizes and resource capacities. Investigating industry-specific factors, such as the role of sectoral regulations, market competition, and environmental impact, could illuminate the unique challenges and opportunities faced by firms in various industries. Additionally, examining external influences, such as international investor pressures, societal expectations, and global regulatory developments, would provide a more holistic view of the factors shaping SRQ. Future studies could also explore the impact of technological advancements, such as the adoption of digital reporting tools and platforms, on improving the accessibility, accuracy, and transparency of sustainability disclosure. Comparative analyses across multiple emerging markets or regions could help identify contextual differences and shared challenges, offering lessons for policymakers and practitioners aiming to globally enhance SRQ. Finally, longitudinal studies that track the evolution of SRQ over time in response to changing governance practices, financial performance, and regulatory environments would provide deeper insights into the drivers of sustainability reporting and its long-term implications for corporate performance and societal impact.