Young Consumers’ Intention to Consume Innovative Food Products: The Case of Alternative Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background and Research Questions Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire and Scaling

3.2. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

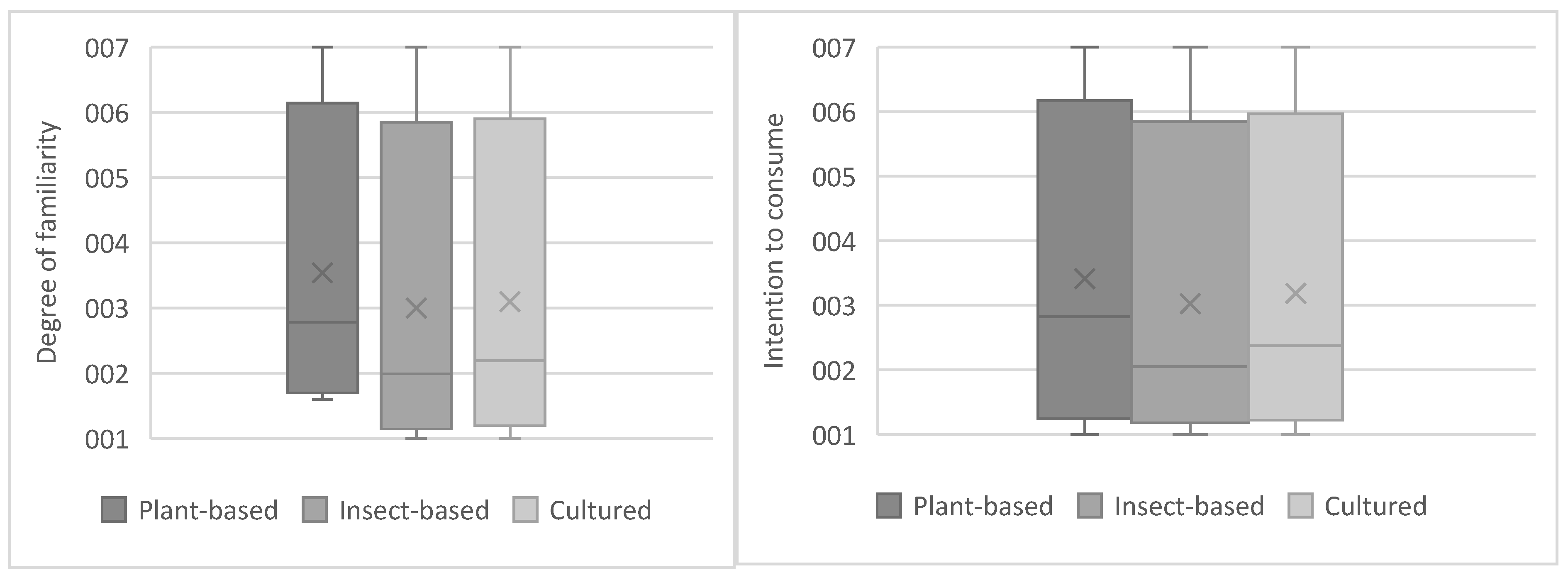

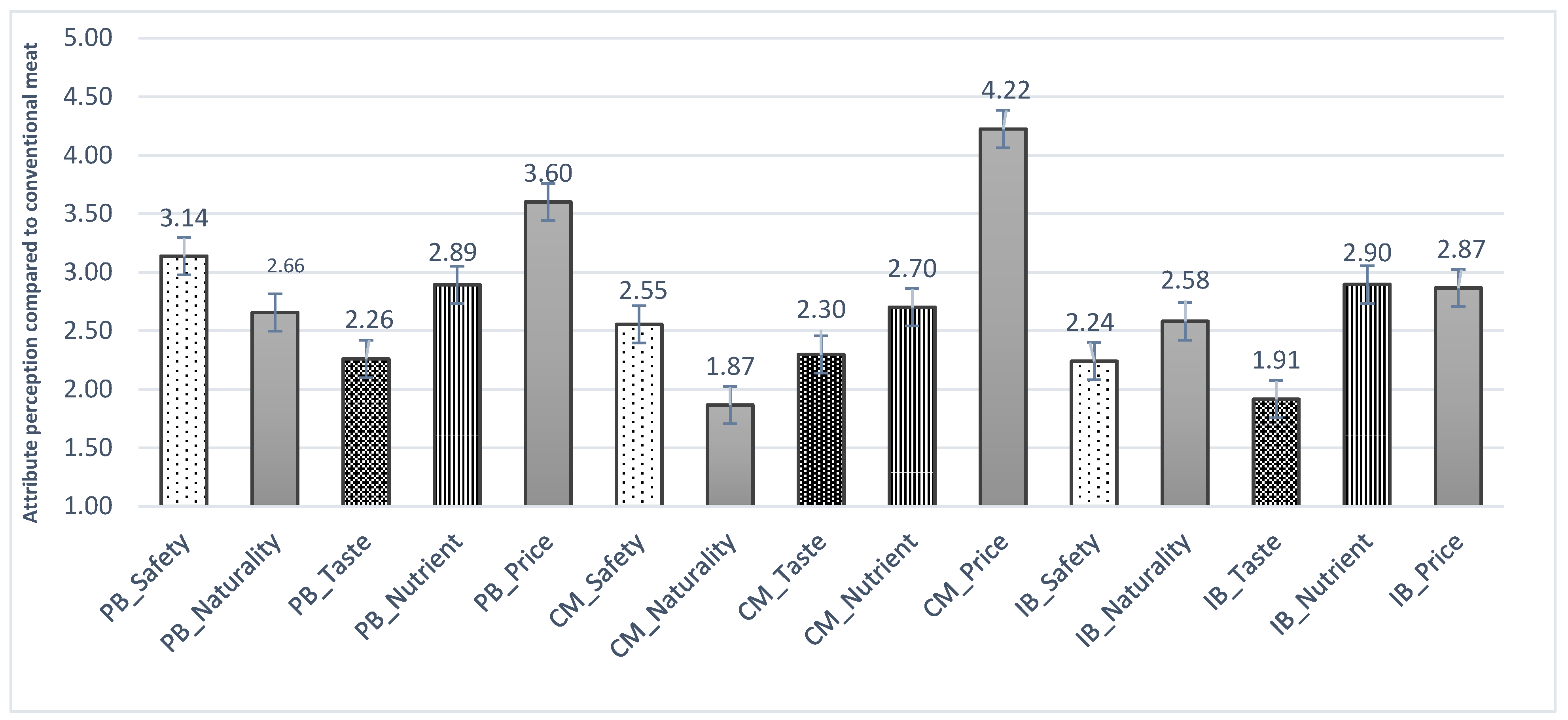

4.1. Descriptive Results

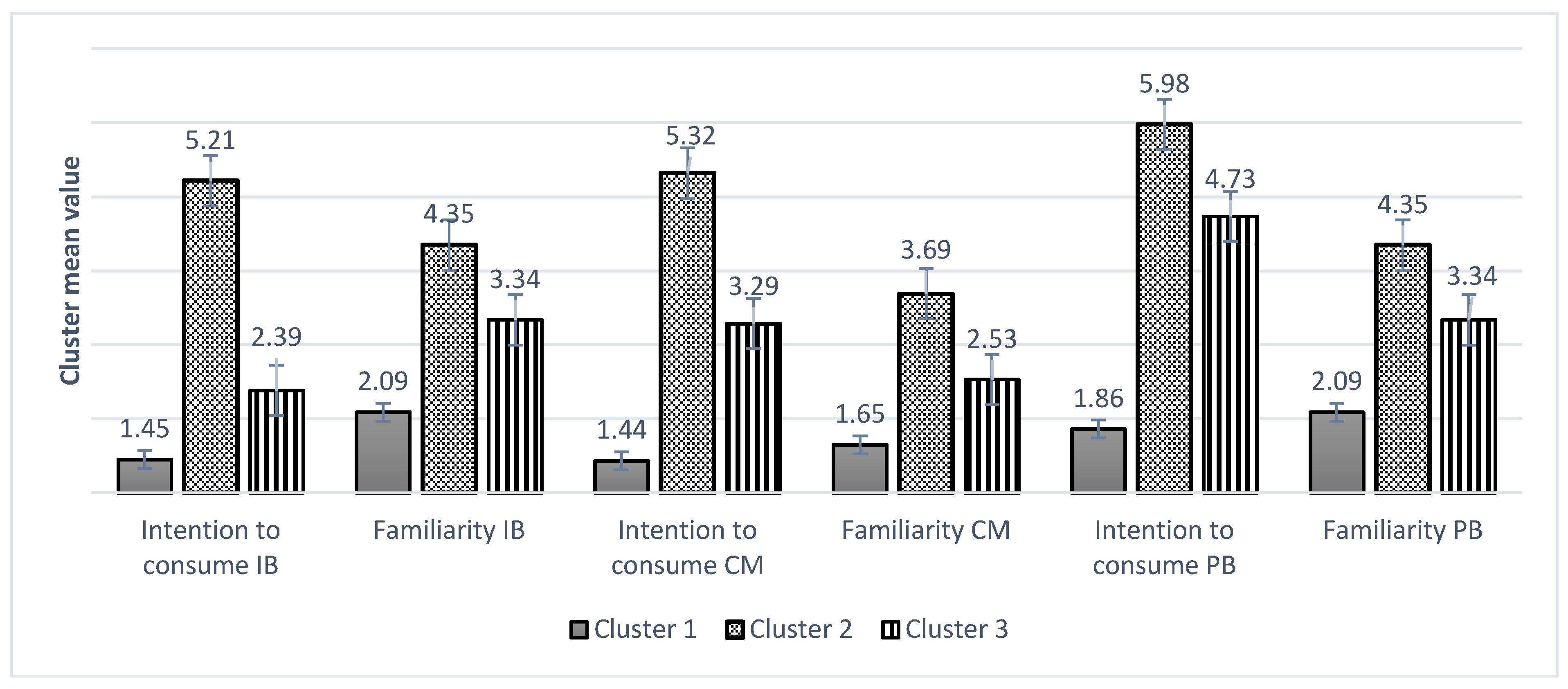

4.2. Multivariate Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHG | Global Greenhouse Gas |

| APS | Alternative Protein Sources |

| IB | Insect-Based |

| PB | Plant-Based |

| CM | Cultured Meat |

References

- Giacalone, D.; Jaeger, S.R. Consumer acceptance of novel sustainable food technologies: A multi-country survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Building a Common Vision for Sustainable Food and Agriculture Principles and Approaches. 2014. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3940e/i3940e.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Alternative Pathways to 2050; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2c6bd7b4-181e-4117-a90d-32a1bda8b27c/content (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezal, C.; Nenert, C.; Gay, H. Meat Protein Alternatives: Opportunities and Challenges for Food Systems’ Transformation; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 182; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2022/09/meat-protein-alternatives_54e42940/387d30cf-en.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- WHO. Red and Processed Meat in the Context of Health and the Environment: Many Shades of Red and Green. Information Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240074828 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- FAO. Shaping the Future of Livestock-Sustainably, Responsibly, Efficiently. 2018. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4d7eff6c-2846-410d-aa37-5a4fa8b1a0f0/content (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Kemper, J.A.; Benson-Rea, M.; Young, J.; Seifert, M. Cutting down or eating up: Examining meat consumption, reduction, and sustainable food beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) Website. Novel Food Section. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/novel-food (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Qazanfarzadeh, Z.; Majzoobi, M.; Sheiband, S.; Oladzadabbasabad, N.; Esmaeili, Y.; Barrow, C.J.; Timms, W. Alternative proteins; A path to sustainable diets and environment. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malila, Y.; Owolabi, I.O.; Chotanaphuti, T.; Sakdibhornssup, N.; Elliott, C.T.; Visessanguan, W.; Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Petchkongkaew, A. Current challenges of alternative proteins as future foods. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choręziak, A.; Rosiejka, D.; Michałowska, J.; Bogdański, P. Nutritional Quality, Safety and Environmental Benefits of Alternative Protein Sources—An Overview. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of the Evidence: WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/349086/WHO-EURO-2021-4007-43766-61591-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- LaLanzoni, D.; Rebucci, R.; Formici, G.; Cheli, F.; Ragone, G.; Baldi, A.; Violini, L.; Sundaram, T.; Giromini, C. Cultured meat in the European Union: Legislative context and food safety issues. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 8, 100722. [Google Scholar]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Nassar, G.; Bouma, J.A. Change Meat Resistance: Systematic Literature Review on Consumer Resistance to the Alternative Protein Transition. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 16, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; De Boni, A.; Saba, A.; Lamy, E.; Minervini, F.; Delgado, A.M.; Sinesio, F. Determinants of consumers’ acceptance and adoption of novel food in view of more resilient and sustainable food systems in the eu: A systematic literature review. Foods 2024, 13, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Dagevos, H. A meta-review of consumer behaviour studies on meat reduction and alternative protein acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 114, 105067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Alvi, T.; Sameen, A.; Khan, S.; Blinov, A.V.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Adli, D.N.; Onwezen, M. Consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: A systematic review of current alternative protein sources and interventions adapted to increase their acceptability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Verain, M.C.; Dagevos, H. Positive emotions explain increased intention to consume five types of alternative proteins. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possidónio, C.; Prada, M.; Graça, J.; Piazza, J. Consumer perceptions of conventional and alternative protein sources: A mixed-methods approach with meal and product framing. Appetite 2021, 156, 104860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luciano, C.A.; de Aguiar, L.K.; Vriesekoop, F.; Urbano, B. Consumers’ willingness to purchase three alternatives to meat proteins in the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, M.; Vainio, A. Towards more environmentally sustainable diets? Changes in the consumption of beef and plant-and insect-based protein products in consumer groups in Finland. Meat Sci. 2021, 182, 108635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.; Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Luxton, S. Alternative protein consumption: A systematic review and future research directions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1691–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, O.; Malleier, M.; Haas, R. Towards sustainable eating habits of generation Z: Perception of and willingness to pay for plant-based meat alternatives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D. Australian Generation Z and the nexus between climate change and alternative proteins. Animals 2022, 12, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, M.H.; Drossel, A.L.; Sassen, R. Sustainable food consumption behaviors of generations Y and Z: A comparison study. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 17, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter de Villiers, M.; Cheng, J.; Truter, L. The Shift Towards Plant-Based Lifestyles: Factors Driving Young Consumers’ Decisions to Choose Plant-Based Food Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, G.; Corrado, S.; De Laurentiis, V.; Sala, S. The Italian meat production and consumption system assessed combining material flow analysis and life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREA IV SCAI-Studio Sui Consumi Alimentari in Italia. 2024. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/web/alimenti-e-nutrizione/-/iv-scai-studio-sui-consumi-alimentari-in-italia (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Akinmeye, F.; Chriki, S.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J.; Ghnimi, S. What factors influence consumer attitudes towards alternative proteins? Food Humanit. 2024, 3, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J. Protein source matters: Understanding consumer segments with distinct preferences for alternative proteins. Future Foods 2023, 7, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plantbased meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.C.; Antonioli, F. Exploring consumers’ attitude towards cultured meat in Italy. Meat Sci. 2019, 150, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Llobell, F.; Giacalone, D.; Chheang, S.L.; Jaeger, S.R. Consumer preference segments for plant-based foods: The role of product category. Foods 2022, 11, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, M.C.; Antonioli, F. Italian consumers standing at the crossroads of alternative protein sources: Cultivated meat, insect-based and novel plant-based foods. Meat Sci. 2022, 193, 108942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, R.; Lim, A.J.; Forde, C.G. A critical appraisal of the evidence supporting consumer motivations for alternative proteins. Foods 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P. If you build it, will they eat it? Consumer preferences for plant-based and cultured meat burgers. Appetite 2018, 125, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, C.; Sanctorum, H. Alternative proteins, evolving attitudes: Comparing consumer attitudes to plant-based and cultured meat in Belgium in two consecutive years. Appetite 2021, 161, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Caputo, V.; Lusk, J.L. Consumer preferences for farm-raised meat, lab-grown meat, and plant-based meat alternatives: Does information or brand matter? Food Policy 2020, 95, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Impact of sustainability perception on consumption of organic meat and meat substitutes. Appetite 2019, 132, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, W.; Dean, D.; Vriesekoop, F.; Aguiar, L.K.; Anderson, M.; Mongondry, P.; Oppong-Gyamfi, M.; Urbano, B.; Luciano, C.A.G.; Jiang, B.; et al. Drivers and inhibitors in the acceptance of meat alternatives: The case of plant and insect-based proteins. Foods 2020, 9, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Barnett, J. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: An updated review (2018–2020). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Strategies towards healthy and sustainable protein consumption: A transition framework at the levels of diets, dishes, and dish ingredients. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Furtwaengler, P.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ evaluation of the environmental friendliness, healthiness and naturalness of meat, meat substitutes, and other protein-rich foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 97, 104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Meat analog as future food: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2020, 62, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piochi, M.; Micheloni, M.; Torri, L. Effect of informative claims on the attitude of Italian consumers towards cultured meat and relationship among variables used in an explicit approach. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubelj, M.; Gleščič, E.; Žvanut, B.; Širok, K. Factors influencing the acceptance of alternative protein sources. Appetite 2025, 210, 107976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Materia, V.C. Insects or not insects? Dilemmas or attraction for young generations: A case in Italy. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A.; Wolańska, W.; Harasym, J.; Piwowar, A.; Kapelko, M. Consumers’ attitudes facing entomophagy: Polish case perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat?(Un) Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewisch, L.; Riefler, P. How social norms and dietary identity affect willingness to try cultured meat. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1014–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H. Social Norms Support the Protein Transition: The Relevance of Social Norms to Explain Increased Acceptance of Alternative Protein Burgers over 5 Years. Foods 2022, 11, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, A.; Niva, M.; Jallinoja, P.; Latvala, T. From beef to beans: Eating motives and the replacement of animal proteins with plant proteins among Finnish consumers. Appetite 2016, 106, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Clausen, M.P.; Jaeger, S.R. Understanding barriers to consumption of plant-based foods and beverages: Insights from sensory and consumer science. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Our daily meat: Justification, moral evaluation and willingness to substitute. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Forleo, M.B. An explorative study of key factors driving Italian consumers’ willingness to eat edible seaweed. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022, 34, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, B.; Michel, F.; Siegrist, M. Which are the most promising protein sources for meat alternatives? Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 119, 105226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, M.; Phillips, C.J. Attitudes to in vitro meat: A survey of potential consumers in the United States. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; You, J.; Moon, J.; Jeong, J. Factors affecting consumers’ alternative meats buying intentions: Plant-based meat alternative and cultured meat. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Bearth, A.; Hartmann, C. The impacts of diet-related health consciousness, food disgust, nutrition knowledge, and the Big Five personality traits on perceived risks in the food domain. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.; Snoek, H.M.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Bouwman, E.P. Sustainable food choice motives: The development and cross-country validation of the Sustainable Food Choice Questionnaire (SUS-FCQ). Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Visschers, V.H.; Hartmann, C. Factors influencing changes in sustainability perception of various food behaviors: Results of a longitudinal study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 46, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Forleo, M.B. The potential of edible seaweed within the western diet. A segmentation of Italian consumers. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 20, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Santo, N.; Califano, G.; Sisto, R.; Caracciolo, F.; Pilone, V. Are university students really hungry for sustainability? A choice experiment on new food products from circular economy. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USTAT-Mur Data. Available online: https://ustat.mur.gov.it/dati/didattica/italia/atenei (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Italian National Institute of Statistics ISTAT Living Conditions and Household Income, Year 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/condizioni-di-vita-e-reddito-delle-famiglie-anni-2023-e-2024/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Lusk, J.L. Consumer research with big data: Applications from the food demand survey (FooDS). Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 99, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, K.; Goddyn, H.; Olsen, S.B.; Bredie, W.L. Identifying behavioral and attitudinal barriers and drivers to promote consumption of pulses: A quantitative survey across five European countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 98, 104455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little jiffy, mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Perito, M.A.; Lupi, C. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: Some hints from Italy. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantechi, T.; Marinelli, N.; Casini, L.; Contini, C. Exploring alternative proteins: Psychological drivers behind consumer engagement. Br. Food J. 2025, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.; Szejda, K.; Parekh, N.; Deshpande, V.; Tse, B. A survey of consumer perceptions of plant-based and clean meat in the USA, India, and China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 432863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, A.; Vecchio, R.; Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Cembalo, L. Willingness to pay for insect-based food: The role of information and carrier. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puteri, B.; Jahnke, B.; Zander, K. Booming the bugs: How can marketing help increase consumer acceptance of insect-based food in Western countries? Appetite 2023, 187, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Nuvoloni, R.; Torracca, B.; Moruzzo, R.; Paci, G. Factors Predicting the Intention of Eating an Insect-Based Product. Foods 2019, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamlin, R.P.; McNeill, L.S.; Sim, J. Food neophobia, food choice and the details of cultured meat acceptance. Meat Sci. 2022, 194, 108964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, E.; Pankiewicz, U. The potential for the use of edible insects in the production of protein supplements for athletes. Foods 2023, 12, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milião, G.L.; De Oliveira, A.P.H.; de Souza Soares, L.; Arruda, T.R.; Vieira, É.N.R.; Junior, B.R.D.C.L. Unconventional food plants: Nutritional aspects and perspectives for industrial applications. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex at birth | Female | 51.5 |

| Male | 45.5 | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | |

| Age (mean and standard deviation) | 21.2 (2.111) | |

| Level of education | High school diploma | 58.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 31.1 | |

| Master’s degree | 10.5 | |

| Residence area | Urban | 33.4 |

| Suburban | 66.6 | |

| Family monthly income (compared with national average) | Below | 21.6 |

| Average | 33.1 | |

| High | 14.5 | |

| Prefer not to say | 30.5 | |

| Sports practice | Yes | 55.5 |

| No | 45.5 | |

| Dietary pattern | Vegan/vegetarian | 5.8 |

| Protein-rich | 21.2 | |

| Gluten/lactose-free | 4.3 | |

| Omnivore | 63 | |

| Other | 5 | |

| Health reasons for a specific diet | Yes | 20 |

| No | 80 |

| Sustainability Concerns (SC) α = 0.847 | Social Norms (SN) α = 0.893 | Health Consciousness (HC) α = 0.882 | Food Neophobia (FN) α = 0.786 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is important to me that the food I eat on a typical day. | SC | |||

| Is produced in an environmentally friendly way. | 0.901 | |||

| Is produced with minimal CO2 emissions. | 0.889 | |||

| Is produced without worker exploitation. | 0.881 | |||

| Is produced without child labour. | 0.870 | |||

| Is produced without environmental resources exploitation. | 0.863 | |||

| Is produced in an animal friendly way. | 0.814 | |||

| Is a seasonal product. | 0.791 | |||

| Is produced without animals being in pain. | 0.769 | |||

| Is a local/regional product. | 0.685 | |||

| FN | ||||

| I am afraid to eat things I have never had before. | 0.817 | |||

| If I don’t know what a food is I won’t try it. | 0.759 | |||

| I don’t trust new foods. | 0.709 | |||

| Ethnic food looks too weird to eat. | 0.692 | |||

| I am very particular about the foods I eat. | 0.611 | |||

| I like to try new ethnic restaurants (R). | 0.087 | |||

| I like foods from different cultures (R). | −0.016 | |||

| I am constantly sampling new and different foods (R). | −0.115 | |||

| I will eat almost anything (R). | −0.013 | |||

| At dinner parties, I will try new foods (R). | −0.022 | |||

| SN | ||||

| I think my friends approve of my consuming meat alternatives. | 0.582 | |||

| I think my family approves of me consuming meat alternatives. | 0.521 | |||

| HC | ||||

| I think it is important to eat healthy. | 0.852 | |||

| My health depends on how and what I eat. | 0.835 | |||

| If you eat healthy, you get sick less often. | 0.834 | |||

| I am willing to give up the food I like in order to eat as healthily as possible. | 0.648 | |||

| % Variance explained | 24.7 | 16.9 | 14.7 | 10.8 |

| % Total variance | 67.1 |

| Cluster 1 n = 131 (39%) | Cluster 2 n = 56 (17%) | Cluster 3 n = 148 (44%) | F | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability concerns | −0.1427689 | 0.2426540 | 0.0644793 | 15.429 | 0.007 |

| Social norms | −0.3105136 | 0.1286644 | 0.5641330 | 16.392 | <0.001 |

| Health consciousness | −0.1495430 | 0.2841913 | 0.0579856 | 9.437 | 0.003 |

| Food neophobia | −0.0054282 | −0.0025637 | 0.0062028 | 2.881 | 0.058 |

| Total Sample | Cluster 1 n = 131 (39%) | Cluster 2 n = 56 (17%) | Cluster 3 n = 148 (44%) | F | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APs contribute to preserving natural resources. | 4.58 (1.638) | 3.92 a (1.620) | 5.69 b (1.271) | 4.89 c (1.473) | 26.347 | 0.000 |

| APs are animal welfare friendly. | 4.87 (1.802) | 4.10 a (1.828) | 6.16 b (1.010) | 5.21 c (1.631) | 29.844 | 0.000 |

| APs contribute to alleviating hunger in developing countries. | 4.09 (1.656) | 3.74 a (1.620) | 4.71 b (1.825) | 4.25 b (1.564) | 16.760 | 0.001 |

| APs contribute to alleviating climate change. | 4.54 (1.716) | 3.98 a (1.754) | 5.33 b (1.632) | 4.84 c (1.530) | 14.684 | 0.001 |

| PB Safety | 3.13 (1.067) | 2.67 a (1.131) | 3.88 b (0.889) | 3.35 c (0.830) | 29.767 | 0.000 |

| PB Naturalness | 2.65 (1.193) | 2.25 a (1.085) | 3.21 b (1.297) | 2.87 a (1.141) | 15.288 | 0.000 |

| PB Expected Taste | 2.25 (1.089) | 1.96 a (1.055) | 2.80 b (1.273) | 2.37 b (0.969) | 11.829 | 0.000 |

| PB Nutritious | 2.89 (1.015) | 2.52 a (1.054) | 3.52 b (0.968) | 3.05 b (0.840) | 20.626 | 0.000 |

| PB Price | 3.60 (1.188) | 3.52 (1.248) | 3.56 (1.237) | 3.92 (1.099) | 1.914 | 0.149 |

| CM Safety | 2.55 (1.185) | 2.10 a (1.083) | 3.45 b (1.086) | 2.71 c (1.115) | 26.298 | 0.000 |

| CM Naturalness | 1.86 (1.075) | 1.55 a (0.937) | 2.38 b (0.167) | 2.00 b (1.087) | 12.198 | 0.000 |

| CM Expected Taste | 2.29 (1.149) | 1.87 a (1.112) | 3.00 b (1.104) | 2.50 c (1.037) | 21.485 | 0.000 |

| CM Nutritious | 2.70 (1.123) | 2.25 a (1.104) | 3.47 b (0.993) | 2.90 c (0.987) | 26.315 | 0.000 |

| CM Price | 3.59 (1.322) | 3.16 a (1.484) | 3.87 b (1.188) | 4.04 b (1.051) | 13.144 | 0.000 |

| IB Safety | 2.23 (1.154) | 1.66 (0.899) | 3.33 (1.202) | 2.46 (1.036) | 49.529 | 0.001 |

| IB Naturalness | 2.58 (1.328) | 2.00 a (1.252) | 3.42 b (1.107) | 2.88 c (1.220) | 29.120 | 0.000 |

| IB Expected Taste | 1.914 (1.057) | 1.50 a (0.897) | 2.90 b (1.205) | 2.00 c (0.920) | 35.328 | 0.000 |

| IB Nutritious | 2.89 (1.316) | 2.29 a (1.350) | 3.90 b (0.905) | 3.17 c (1.087) | 35.854 | 0.000 |

| IB Price | 2.86 (1.263) | 2.54 a (1.302) | 3.01 b (1.286) | 3.38 b (1.139) | 8.957 | 0.002 |

| Cluster 1 n = 131 (39%) | Cluster 2 n = 56 (17%) | Cluster 3 n = 148 (44%) | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 44.3 | 52.4 | 45.5 | 0.084 |

| Female | 50.4 | 45.2 | 54.5 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 5.3 | 2.4 | - | ||

| Mean age * | 20.6 | 21.9 | 21.2 | <0.001 | |

| Family monthly income compared with national average | Below | 18.3 | 26.2 | 24.2 | 0.089 |

| Average | 18.3 | 26.2 | 24.2 | ||

| High | 14.5 | 16.7 | 13.6 | ||

| n.d. | 42.7 | 23.8 | 26.5 | ||

| Residence area | Urban | 20.6 | 33.6 | 24.8 | 0.242 |

| Suburban | 79.4 | 66.4 | 75.2 | ||

| Dietary pattern | Omnivore | 67.9 | 59.5 | 74.2 | 0.002 |

| Vegan/vegetarian | - | 5.4 | 0.8 | ||

| High-protein diet | 27.3 | 19 | 20.5 | ||

| Gluten/lactose-free | 2.3 | 5.3 | 2.4 | ||

| Other | 2.5 | 10.8 | 2.1 | ||

| Sports practice | Yes | 60.3 | 66.7 | 46.2 | 0.019 |

| No | 39.7 | 33.3 | 53.8 | ||

| Changes in meat consumption | Not reduced | 76.3 | 40.5 + | 56.1 | <0.001 |

| Reduced for health reasons | 10.7 | 33.3 | 19.7 | ||

| Reduced for environmental concerns | 3.8 | 4.8 | 13.6 | ||

| Reduced for animal welfare | 9.2 | 21.4 | 10.6 | ||

| Future intention to change meat consumption | Not reduce | 52.7 | 31 + | 24.2 | <0.001 |

| Reduced for health reasons | 22.1 | 33.3 | 22.0 | ||

| Reduced for environmental concerns | 5.3 | 11.9 | 22.0 | ||

| Reduced for animal welfare | 19.8 | 23.8 | 31.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mariani, A.; Annunziata, A. Young Consumers’ Intention to Consume Innovative Food Products: The Case of Alternative Proteins. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136116

Mariani A, Annunziata A. Young Consumers’ Intention to Consume Innovative Food Products: The Case of Alternative Proteins. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136116

Chicago/Turabian StyleMariani, Angela, and Azzurra Annunziata. 2025. "Young Consumers’ Intention to Consume Innovative Food Products: The Case of Alternative Proteins" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136116

APA StyleMariani, A., & Annunziata, A. (2025). Young Consumers’ Intention to Consume Innovative Food Products: The Case of Alternative Proteins. Sustainability, 17(13), 6116. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136116