Comparison of Governance Policies for Agroforestry Initiatives: Lessons Learned from France and Quebec

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

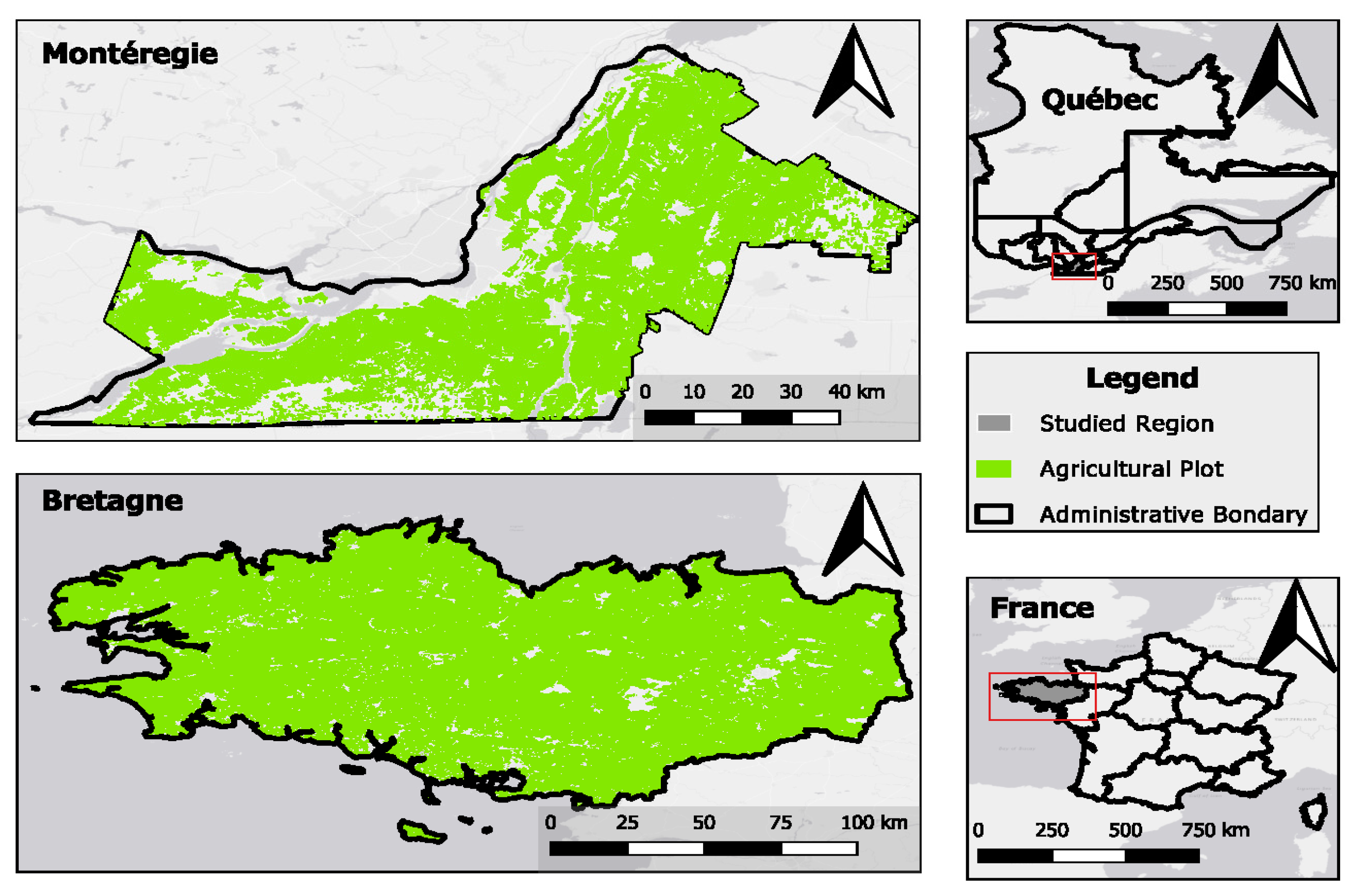

2.1. Study Area

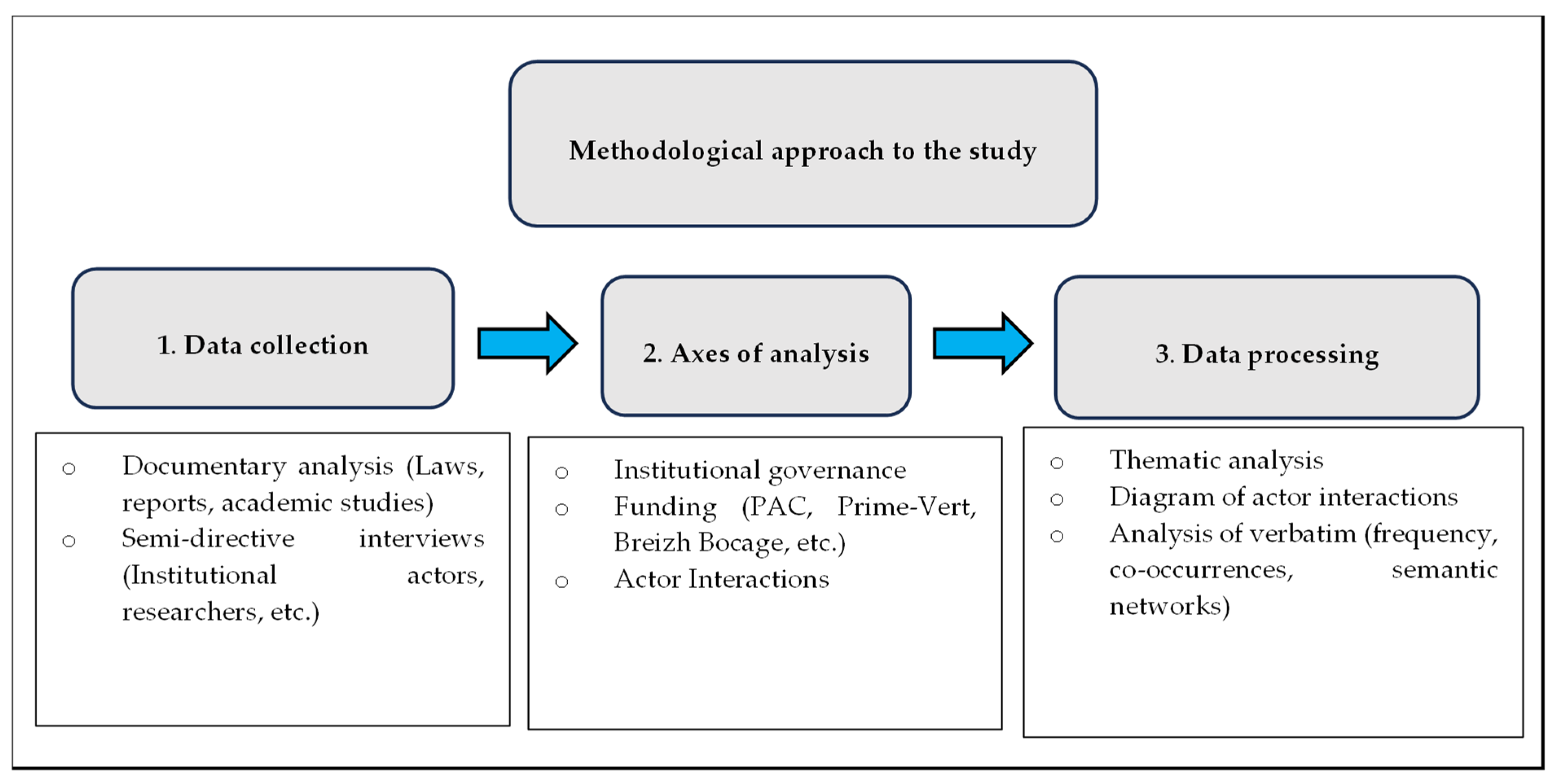

2.2. Materials and Methods

2.2.1. Collection Tools and Actors Involved

2.2.2. Analysis Method

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Agroforestry Policies in Quebec and France

3.1.1. Institutional and Organizational Actors in Agroforestry in Quebec and France

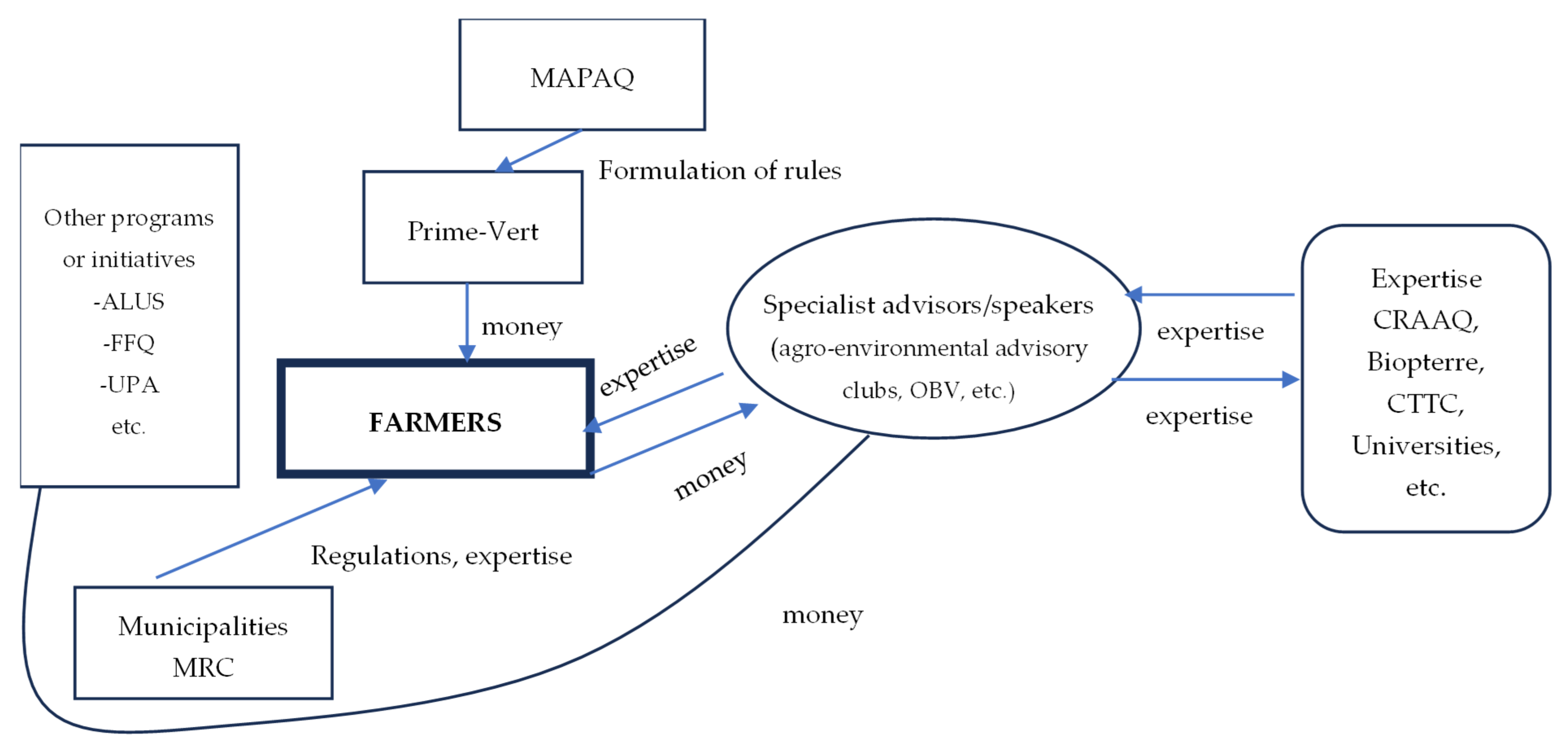

- In Quebec

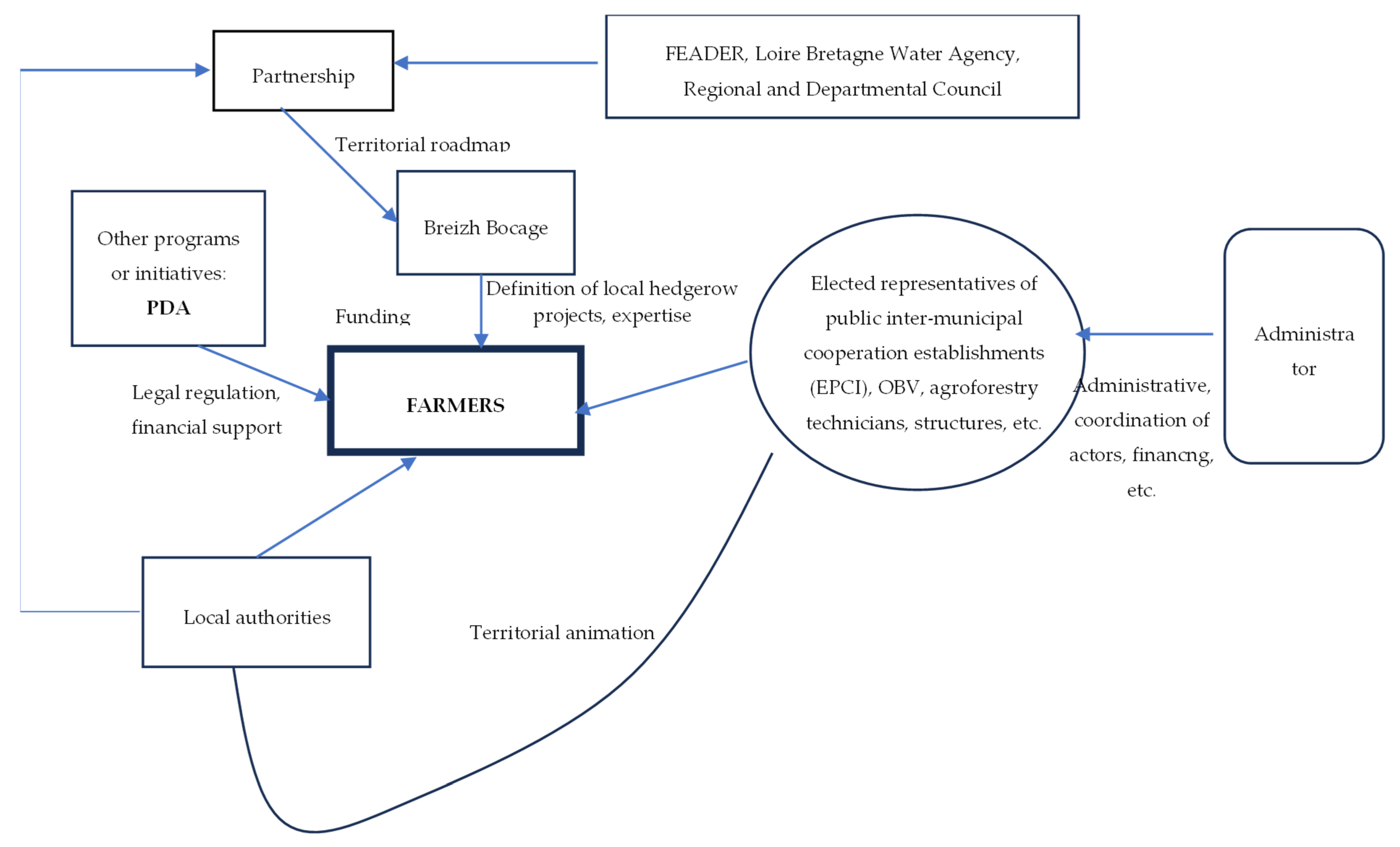

- In France (Brittany region)

3.1.2. Political Frameworks Governing Agroforestry Practices in Quebec and France

- Agroforestry policies in Quebec

- Agricultural, forestry, environmental, and regional development policy in France

3.2. Focus on the Specific Features of the Prime-Vert (Montérégie) vs. Breizh Bocage (Brittany) Programs

3.2.1. Analysis of the Prime-Vert Program

- Specific features of the Prime-Vert program

- Perception of stakeholders on the approach of this program

- Strengths of the Prime-Vert Program According to Stakeholders

- Weaknesses of the Prime-Vert Program According to Stakeholders

- Suggestions from Stakeholders regarding the Implementation of the Prime-Vert Program

3.2.2. Analysis of the Breizh Bocage Program

- Specific features of the Breizh Bocage program compared to the Prime-Vert program

- Limits of the Breizh Bocage Program

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romanova, O.; Gold, M.A.; Hall, D.M.; Hendrickson, M.K. Perspectives of Agroforestry Practitioners on Agroforestry Adoption: Case Study of Selected SARE Participants. Rural Sociol. 2022, 87, 1401–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulya, N.A.; Harianja, A.H.; Sayekti, A.L.; Yulianti, A.; Djaenudin, D.; Martin, E.; Hariyadi, H.; Witjaksono, J.; Malau, L.R.E.; Mudhofir, M.R.T.; et al. Coffee agroforestry as an alternative to the implementation of green economy practices in Indonesia: A systematic review. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8, 762–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Agroforestry Systems and Practices for Sustainable Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, M.; Khanal, A.; Bhatt, D.; Dahal, D.; Giri, S. Agroforestry systems in Nepal: Enhancing food security and rural livelihoods–a comprehensive review. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzer, V.; Mo’zdzierz, M.; Kuijpers, R.; Schouten, G.; Juju, D.B. Gender and forest resources in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 163, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milder, J.C.; Majanen, T.; Scherr, S.J. Performance and potential of conservation agreements for promoting sustainable development in tropical landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S.M.; Gordon, A.M. Temperate agroforestry: Key elements, current limits and opportunities for the future. In Temperate Agroforestry Systems; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 274–298. [Google Scholar]

- Angeon, V.; Larade, A. La gouvernance des trames vertes et bleues: De la nécessité d’une approche opérationnelle et réflexive. Manag. Avenir 2017, 97, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sotteau, D. Les politiques de soutien à l’agroforesterie en France: Évaluation et perspectives. Rev. Int. L’environ. L’agroforesterie 2021, 14, 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Dupraz, C.; Liagre, F. Agroforesterie: Des Arbres et des Cultures; Éditions France Agricole: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chever, T.; Parant, S.; Gonçalves, A. Evaluation du programme Breizh Bocage. Bilan de mise en œuvre, premiers impacts sur les territoires et pistes d’amélioration pour la future programmation. Marché subséquent N°5, Lot 2, Évaluation du FEADER PDR Bretagne. 2021. Available online: https://www.bretagne.bzh/app/uploads/sites/5/2021/11/Rapport-final-Evaluation-du-programme-Breizh-Bocage-2-Lot-2.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Rivest, D.; Lorent, M.; Olivier, A.; Messier, C. Soil biochemical properties and microbial resilience in agroforestry systems: Effects on wheat growth under controlled drought and flooding conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463–464, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, G.; Olivier, A. Contexte politique québécois et pratique de l’agroforesterie: État des lieux. For. Chron. 2015, 91, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, D.; Olivier, A. Intercropping with deciduous trees: What potential for Quebec? For. Chron. 2007, 83, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, E.; Thiel, A.; McGinnis, M.; Kellner, E. Empirical research on polycentric governance: Critical gaps and a framework for studying long-term change. Policy Stud. J. 2024, 52, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, C.L. A Comparative Review of Agroforestry Legal Frameworks in France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Ireland. Master’s Thesis, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelier-Rous, N.; Laroche, G.; Durocher, È.; Rivest, D.; Olivier, A.P.; Liagre, F.; Cogliastro, A. Temperate agroforestry development: The case of Québec and of France. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DRAAF. Synthèse agricole du Finistère (Édition 2022, N°11). 2022. Available online: https://draaf.bretagne.agriculture.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/11_essentiel_synthese_29.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- DRAAF. Synthèse Agricole de l’Ille-et-Vilaine (N°12). 2022. Available online: https://draaf.bretagne.agriculture.gouv.fr/essentiel-no12-synthese-agricole-et-agroalimentaire-de-l-ille-et-vilaine-a1546.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Insee. Identité Agricole des Régions. 2021. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/fichier/5039859/FET2021-7.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Larbi-Youcef, Y. Les Politiques Agroenvironnementales au Québec: Enjeux, Perspectives et Recommandations (Mémoire de Maîtrise). Université de Sherbrooke, Centre Universitaire de Formation en Environnement. 2017. 160p. Available online: https://usherbrooke.scholaris.ca/items/efe5de42-3bb1-4c79-a923-1044373667d6 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MAPAQ. Plan de Développement de la Zone Agricole. 2020. Available online: https://www.mapaq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/Productions/developpementregional/Pages/PDZA.aspx (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Cozzolino, I.; Ferraro, M. Document clustering. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2022, 14, e1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, V.L. The vocabulary of agriculture semi-popularization articles in English: A corpus-based study. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2015, 39, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguerie, N.; Montastier, E.; Maoret, J.J.; Roussel, B.; Combes, M.; Valle, C.; Villa-Vialaneix, N.; Iacovoni, J.; Martinez, J.A.; Holst, C.; et al. Determinants of human adipose tissue gene expression: Impact of diet, sex, metabolic status, and cis genetic regulation. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1002959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anel, B.; Cogliastro, A.; Olivier, A.; Rivest, D. Une Agroforesterie Pour le Québec: Document de Réflexion et D’orientation; Comité Agroforesterie, Centre de Référence en Agriculture et Agroalimentaire du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2017; 73p. [Google Scholar]

- Gaboury-Bonhomme, M.-E. L’action Publique en Agriculture au Québec de 1990 à 2010: Acteurs, Référentiels et Instruments Politiques. Ph.D. Thesis, École Nationale D’administration Publique, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2018; 436p. [Google Scholar]

- Kanga, P.W. Analyse de L’influence des Programmes Agroenvironnementaux sur L’adoption des Haies Brise-Vent et des Bandes Riveraines par les Agriculteurs: Le cas de la MRC de Kamouraska. Mémoire de Maitrise; Université Laval: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MAA. Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté Alimentaire. 2023. Available online: https://agriculture.gouv.fr/ (accessed on 17 April 2025). (In English).

- ADEME. Les Sols à la Croisée des Enjeux Agricoles et Climatiques. 2021. ADEME Infos. Available online: https://infos.ademe.fr/lettre-recherche-mai-2021/sol-enjeux-agricoles-et-climatiques/ (accessed on 17 April 2025). (In English).

- Béral, C.; Andueza, D.; Ginane, C.; Bernard, M.; Liagre, F.; Girardin, N.; Emile, J.C.; Novak, S.; Grandgirard, D.; Deiss, V.; et al. Agroforesterie en Système D’élevage Ovin: Étude de son Potentiel dans le Cadre de L’adaptation au Changement Climatique; INRAE: Paris, France, 2018; 158p. [Google Scholar]

- ADEME. PCAET et démarche Territoire Engagé Transition Ecologique. 2022. Available online: https://www.territoiresentransitions.fr/actus/87/pcaet-et-demarche-territoire-engage-transition-ecologique-climat-air-energie-un-duo-gagnant (accessed on 17 April 2025). (In English).

- Tartera, C.; Rivest, D.; Olivier, A.; Liagre, F.; Cogliastro, A. Agroforesterie en développement: Parcours comparés du Québec et de la France. For. Chron. 2012, 88, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogstad, G. Politique de L’agriculture et de L’alimentation. l’Encyclopédie Canadienne, 31 juillet 2014, Historica Canada. 2014. Available online: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/fr/article/agriculture-et-de-lalimentation-politique-de-l (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MFFP. Règlement sur L’aménagement Durable des forêts du Domaine de l’État. 2023. Available online: https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/document/rc/A-18.1,%20r.%200.01 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Gaillard, M. Les Réformes de la PAC. 2018. Available online: https://www.vie-publique.fr/parole-dexpert/38645-reformes-de-la-politique-agricole-commune-pac-depuis-1992 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MAA. La PAC, qu’est ce que c’est? Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté Alimentaire. 2019. Available online: https://agriculture.gouv.fr/la-pac-quest-ce-que-cest (accessed on 17 April 2025). (In English).

- Carvin, O.; Saïd, S. Contrat agro-environnemental et participation des agriculteurs. Écon. Rural. 2020, 373, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, J. L’agroforesterie, une Aventure de Développement Durable pour L’agriculture Québécoise? Doctoral Thesis, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watteaux, M. Rewriting the history of bocage: An asset for the valorization of hedgerow landscapes? Pour Altern. Écon. 2023, 247, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cogliastro, A.; D’Orangeville, L. Organizing the coexistence of agriculture and forest in Montérégie. In Mémoire Présenté à la Commission sur L’avenir de L’agriculture et de L’agroalimentaire Québécois (CAAAQ); Institut de Recherche en Biologie Végétale & Jardin Botanique de Montréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2007; 14p. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.; Dumont, A.; Maurice, M.P.; Campeau, S. Entre sentiment de responsabilité et aversion pour l’arbre: Les bandes riveraines vues par les agriculteurs. VertigO 2021, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Observatoire de L’environnement en Bretagne (OEB). Le Bocage Breton: Quel Avenir? Eau, Biodiversité, Paysage. 2008. 68p. Available online: https://bretagne-environnement.fr/bocage-breton-avenir-eau-biodiversite-paysage (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Van den Hove, S. Participatory approaches to environmental policy-making: The European Commission Climate Policy Process as a case study. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 33, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaga-Mendez, A.; Kolinjivadi, V.; Bissonnette, J.F.; Dupras, J. Mixing public and private agri-environment schemes: Effects on farmers participation in quebec, canada. Int. J. Commons 2020, 14, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADEME. Notre Organisation—Agence de la Transition Écologique. Agence de la Transition Écologique. 2023. Available online: https://www.ademe.fr/lagence/notre-organisation/ (accessed on 17 April 2025). (In English).

- Mottershead, D.; Maréchal, A. Promotion of Agroecological Approaches: Lessons from Other European Countries, a Report for the Land Use Policy Group.: Institute for European Environmental Policy. 2017. Available online: https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/5826624064323584 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- INRAE. L’agroforesterie, Priorité de Recherche au Cœur de la Transition Agro-Écologique. INRAE. 2019. Available online: https://www.inrae.fr/actualites/lagroforesterie-priorite-recherche-au-coeur-transition-agro-ecologique (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Zaga-Mendez, A.; Kolinjivadi, V.; Bissonnette, J.F.; Dupras, J. Entangling Conservation Schemes and Its Effects on Farmers’ Participation: The Case of Two Agri-Environmental Incentives in Quebec. In Proceedings of the XVII Biennial IASC Conference “In Defense of the Commons: Challenges, Innovation, and Action”, Lima, Peru, 1–5 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MAPAQ. Prime-Vert Volet 3 Appui au Développement et au Transfert de Connaissances en Agroenvironnement. 2019. Available online: https://www.mapaq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/Productions/md/programmesliste/agroenvironnement/sous-volets/volet3/Pages/Volet-3.aspx (accessed on 15 April 2025).

| Verbatim | Actor Type/Field | |

|---|---|---|

| Quebec (Montérégie) | France (Brittany) | |

| 1 | Research Center | National organization specializing in agroforestry |

| 2 | Agricultural Council | Research, development, and training structures |

| 3 | Independent agroforestry expert | National research organization |

| 4 | Protection of biodiversity | Regional water management body |

| 5 | Advisory Club | Other regional body |

| 6 | Regional public body (forest/agroforestry) | Regional timber management organization |

| 7 | Environment | Other regional water management body |

| Comparison Criteria | Quebec Policies | French Policies |

|---|---|---|

| Governance structure | Multi-level (federal, provincial, and municipal) with a central role for the provinces | Decentralized with strong state involvement through the CAP |

| Status of agroforestry | Low recognition as a cross-cutting system between agriculture and forestry | Official recognition in agricultural policies |

| Role of municipalities | Important especially from the MRCs | Support from local authorities and water agencies |

| Policy instruments | Climate plans for a green economy 2030, Environmental laws (LQE), programs (Ex: Prime-Vert) | Successive reforms of the CAP, agri-environmental measures, PDA (2015–2020), territorial plans (CTE and CAD) |

| Main limits | Institutional fragmentation, lack of unified national policy, weak financial support, and difficult intersectoral coordination | Administrative complexity and lack of funding for long-term support. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dossa, K.F.; Bissonnette, J.-F.; Soudet, T. Comparison of Governance Policies for Agroforestry Initiatives: Lessons Learned from France and Quebec. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136114

Dossa KF, Bissonnette J-F, Soudet T. Comparison of Governance Policies for Agroforestry Initiatives: Lessons Learned from France and Quebec. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136114

Chicago/Turabian StyleDossa, Kossivi Fabrice, Jean-François Bissonnette, and Thomas Soudet. 2025. "Comparison of Governance Policies for Agroforestry Initiatives: Lessons Learned from France and Quebec" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136114

APA StyleDossa, K. F., Bissonnette, J.-F., & Soudet, T. (2025). Comparison of Governance Policies for Agroforestry Initiatives: Lessons Learned from France and Quebec. Sustainability, 17(13), 6114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136114