1. Introduction

Cash in circulation continues to rise today, despite the digitalisation of economies and apparent trends toward transitioning payments to electronic channels. While digital wallets, card-based payments and mobile solutions powered by credit transfers are rapidly gaining adoption, the value of physical cash in circulation is increasing in most countries [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This trend is driven largely by precautionary and hoarding motives, as cash is still viewed by many as a secure asset [

5,

6,

7]. The increase in the volume of physical currency affects the manner in which countries formulate their monetary policies and ensure access to cash [

8,

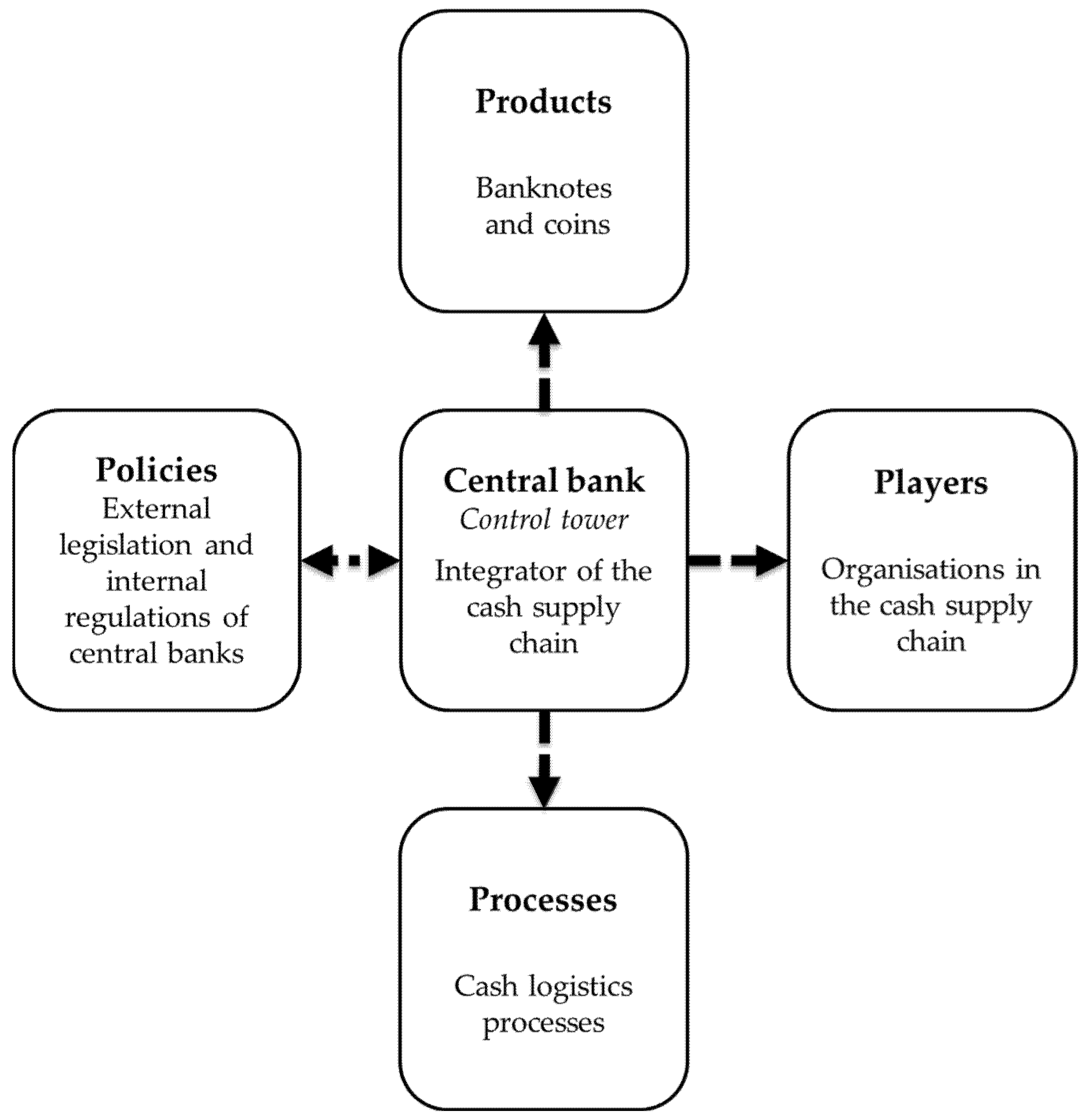

9]. Consequently, there is a pressing need to manage rising cash volumes in a cost-efficient and process optimal manner. To tackle this issue, it is essential to implement a robust sustainable cash logistics management model that is both universal and adaptable, and that is capable of integrating state-of-the-art innovations, regulatory changes and other critical aspects of modern cash flow management. This paper aims to address this need by introducing the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model, where 4P represents Product, Players, Processes and Policies (see

Section 2 for further explanation). The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents a literature review.

Section 3 outlines the research methodology.

Section 4 presents the key findings from empirical studies conducted in Poland—a country with a population of nearly 40 million—which served as the foundation for developing the model and proposing improvements to cash logistics.

Section 5 introduces the proposed model.

Section 6 explores the suggested refinements to cash logistics. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Cash usage for transactions is declining globally. According to the European Central Bank’s 2024 study on consumer payment attitudes in the euro area (SPACE), just over half of all payments (52%) were made in cash, down from 59% in 2022 [

10]. In terms of transaction value, card payments already accounted for a larger share (45%) of POS transactions than cash (39%). However, the total value of cash in circulation continues to rise. This simultaneous decline in cash payments and increase in cash in circulation is commonly referred to in the economic literature as the “cash paradox” or “banknotes paradox” [

11,

12]. This phenomenon is driven by the tendency to hoard cash for contingency purposes, which intensifies during periods of crisis, uncertainty and low interest rates [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Individuals tend to treat physical cash as a safe haven asset during times of market turbulence or economic disruption, viewing it as more stable and reliable than deposit money.

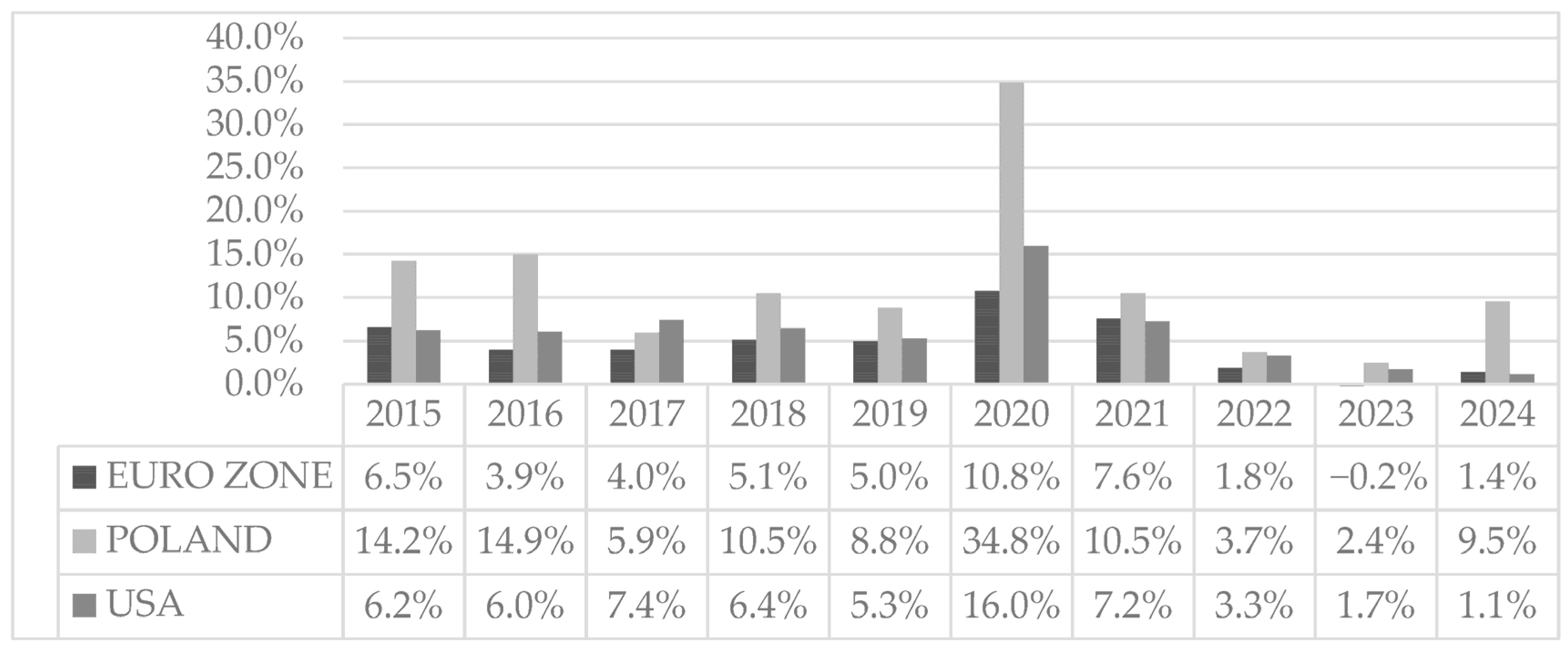

Figure 1 illustrates the annual growth rates of cash in circulation over the period of 2015–2024 in selected regions and countries, including the eurozone, the USA and Poland. In the eurozone the value of banknotes increased by as much as 56.3% (approximately 571.8 billion EUR), while in Poland it reached 190% (approximately 270.4 billion PLN). It is evident that extraordinary events, such as the pandemic or the Russian invasion of Ukraine, reinforce the propensity to hold cash. The cash paradox is a global phenomenon.

This literature review highlights a growing interest in cash circulation logistics management among the various aspects studied. Researchers examining cash logistics emphasise that the increasing volume and value of cash in circulation give rise to three key challenges [

6,

20,

21,

22]:

Rising cash handling costs;

Difficulties in efficient cash management;

Security-related complications within the cash circulation system.

To respond to these challenges innovative methods and tools are required. Thus, this article develops a 4P Cash Logistics Management Model.

It builds on a modern logistical concept of control tower which is primarily aimed at improving the efficiency of supply chain processes and enhancing the quality of both short- and long-term decision-making [

23]. In business practice, a logistical control tower serves as a central hub that integrates technology and processes, enabling the efficient flow of products from production sites to end customers, regardless of the complexity of the supply chain. From the perspective of the cash supply chain, the main objective of this concept is to optimise cash logistics processes along the entire chain and improve the quality of decision-making at each stage [

24]. The concept of a logistical control tower is closely related to another idea commonly found in the economic literature—the concept of the focal company, which adopts a network perspective in supply chain management [

25,

26]. In practice, this construct has been widely applied in the automotive industry, where it has proven particularly effective in addressing the complexities of logistics processes involving numerous subcontractors [

27]. A focal company is a key organisation within a network—typically a supply or value chain—that plays a central coordinating role. It is usually the firm around which the network is structured and which drives or influences decisions, strategies and relationships among other actors in the system.

Given the characteristics of the cash cycle—where cash moves through the cash supply chain to end users and then returns from merchants back into the wholesale system—a clear parallel emerges with logistics management theories, particularly the framework for reverse logistics [

28]. Reverse logistics, widely used in promoting the circular economy, enables the reuse and recycling of products and materials, contributing to resource optimisation by reducing inventory and waste. In the context of cash logistics, institutions may aim to shorten the return path of cash by promoting lower-level (local) circulation, facilitated by automated devices such as recyclers, including back-office recyclers employed in large retail outlets. This approach aligns closely with the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model and its intersecting components, as described below.

The cash logistics literature identifies five typical activities within closed-loop supply chains [

20]: (1) product acquisition, (2) reverse logistics, (3) testing, sorting and disposition, (4) refurbishment and (5) redistribution. These stages translate in the cash cycle to customers and merchants depositing cash; banks and cash handling companies collecting cash; sorting by denomination and fitness; reusing notes that are fit for purpose; and ultimately returning unfit notes to the central bank for destruction. The practice of cash logistics matches with the principles of green logistics, also referred to as sustainable or eco-friendly logistics. This approach within supply chain management aims to minimise the environmental impact of logistics operations by adopting environmentally responsible practices in areas such as transportation, packaging and related activities. Its primary goals include reducing carbon emissions, waste and energy consumption [

29].

The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model, rooted in the network perspective theory of supply chain management, captures the distinctive characteristics of the cash supply chain, which functions as a closed-loop system where cash circulates between institutions and the public. Cash demand is driven by consumers, small businesses and merchants accepting cash payments. The model applies the 4P approach to logistics, offering a structured framework for managing cash flows efficiently [

20]. 4P stands for:

Product;

Players;

Processes;

Policies.

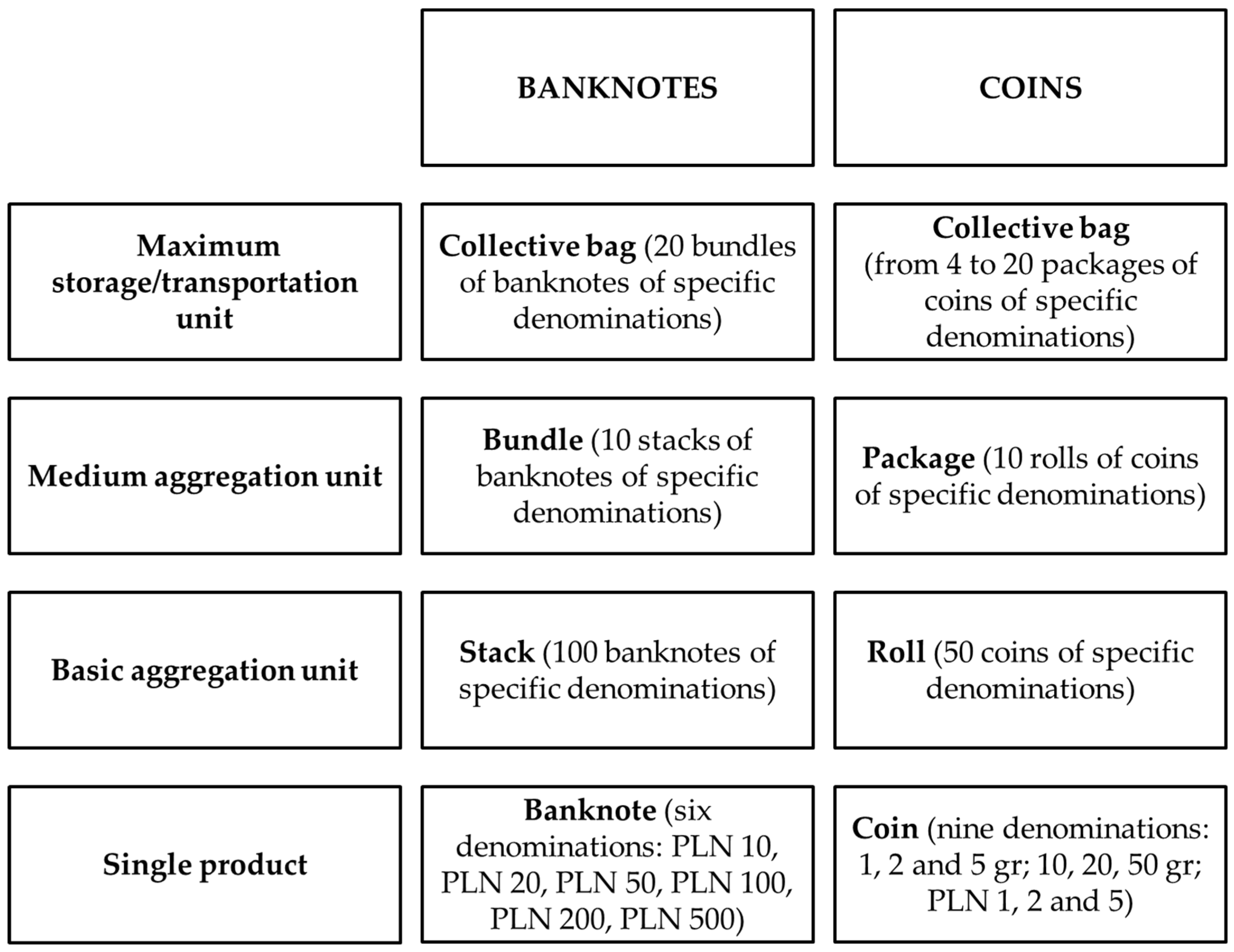

Cash, as a product—the first logistics “P”—refers to physical banknotes made from cotton or polymer and coins minted from metal. Cash must be fit for purpose. New banknotes and coins are produced at the request of the central bank, while used ones are withdrawn from circulation [

30]. If they still meet quality standards, they are recirculated. Smaller banknote denominations typically have shorter life cycles, as they change hands more frequently and are handled more often by recyclers, ATMs and cash sorting machines, causing them to wear out more quickly. Coins and higher banknote denominations live longer.

The key players—the second logistics “P”—in cash logistics encompass institutions engaged in wholesale cash management, including the central bank, commercial banks, banknote and coin producers, cash-in-transit (CIT) companies, cash handling centres and ATM deployers.

Each institution within the cash supply chain is responsible for various cash processes—the third logistics “P”—such as the transport, sorting and quality testing of cash. Consumers and small businesses primarily access cash through ATMs, with smaller amounts obtained via bank branches and cashback services in shops. Surplus cash is returned to banks through cash deposit machines and bank branches.

All these processes are regulated by laws and industry standards, collectively representing the fourth logistics “P”—policies that define the rules for, e.g., how cash is produced and safeguarded against counterfeiting, securely transported, counted, sorted, packed and ultimately destroyed.

The literature distinguishes between different cash cycle management models (

Table 1).

The European Payments Council [

21] grouped European countries into different cash cycle management models as follows:

Central models: France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia.

Joint-venture models: Austria, Belgium;

Delegation models: Finland, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, Slovenia, the United Kingdom;

Transfer models: Norway, Sweden.

Each model has its advantages and disadvantages. Central models offer greater control over the cash supply system, while delegation and transfer models provide more flexibility and entail lower costs for the public sector. Some may argue that in countries with more delegated models, the quality of cash in circulation may be lower than in those where the central bank more frequently takes possession of circulating cash to perform quality checks. On the other hand, if clear standards are established and consistently followed by banks and private cash handling companies, the quality of cash in circulation can be effectively maintained.

While countries may differ in the extent to which processes and responsibilities are transferred from the central bank to the private sector, the major players and core processes involved in cash handling—such as transport, counting, sorting and packing—are largely consistent across jurisdictions. As a result, research findings from one country can often be applied to others, though some local variations must be acknowledged. Challenges more prominent in one group of countries—such as those related to automation and the digitisation of certain tasks—may have already been addressed elsewhere.

Poland, selected for closer examination of its cash logistics processes, exhibits several characteristics that make it a valuable case for study. First, by European standards, it is a relatively large country with a centralised cash management model. Second, its economy is rapidly digitising, with non-cash payments becoming increasingly common, while at the same time experiencing a significant rise in cash in circulation—an illustration of the cash paradox.

3. Research Methodology

In our research we applied the principle of research triangulation by combining the following:

The study was conducted in two stages. The first stage involved a case study of a cash handling centre, while the second stage comprised a survey of market participants within the cash supply chain.

The case study provided an in-depth insight into the operations of a cash handling centre in Warsaw, part of a leading cash logistics operator in Poland. It combined participant and non-participant observations. A distinctive feature of this empirical research was the use of an action research methodology, with one of the article’s authors undertaking temporary employment within the organisation under study. This approach enabled direct, unstructured interviews with other employees of the cash processing company, an analysis of internal documents and the application of shadowing.

Shadowing is a research method in which the researcher closely follows an employee as they perform their professional duties, effectively becoming the employee’s “shadow” and observing their daily work activities [

35]. Although rarely employed due to its time-intensive nature, participatory action-research methods offer valuable insights that would be difficult to obtain through more conventional research techniques.

In addition to identifying organisational problems related to cash processing management, this method enabled the creation of detailed process maps for key roles within the cash handling centre.

The results of the case study were instrumental in drafting a questionnaire, which served as the primary research tool in the second stage of this empirical study. The survey included multiple questions closely related to cash logistics processes and the issues identified during the first stage of the study. Respondents were invited to share their views on information flow, the standardisation of various cash logistics processes and subprocesses, the roles of key actors within the cash cycle, the regulatory framework, deficiencies within the cash supply chain and potential solutions. The survey made it possible to generalise the research findings to the entire cash industry within the country.

The survey of participants in the Polish cash supply chain was conducted in collaboration with the Polish Cash Handling Companies Organisation (POFOG) and the Polish Bank Association (ZBP). The study proved suitable for recognising relationships and phenomena within the Polish cash circulation system and helped identify the factors influencing management efficiency within this system. The questionnaire was distributed to key organisations within the Polish cash circulation system. A total of 30 completed questionnaires were received, representing, by number, 83% of cash handling companies, 44% of commercial banks, 50% of technology providers for cash process automation and, additionally, several large retailers, making the study sufficiently representative of the cash supply chain in Poland. Such broad coverage of market participants justifies the generalisation of the results and recommendations to the entire cash industry in Poland, while also providing a useful benchmark for other countries and regions.

4. Results

Cash logistics in Poland is managed by a few specialised cash handling companies, the Polish Post, cooperative banks and one major commercial bank that has not outsourced its cash handling operations to a professional cash logistics provider. These companies deliver cash-in-transit (CIT) services and operate cash centres, where banknotes and coins are counted, sorted, packed and securely stored—with all processes meticulously recorded in parallel. The transportation and processing of cash combined are commonly referred to as cash handling. In recent years, the cash handling market in Poland has become more consolidated—a trend also observed in other countries. All cash handling companies operate under the same legal framework and employ similar technologies, resulting in a noticeable degree of uniformity in cash handling processes across all cash centres.

The first stage of the research was conducted at a cash centre in Warsaw, where one of the co-authors worked alongside other employees, performing the same tasks and shadowing their daily activities, with all staff being aware of the ongoing study. This approach enabled the researcher to employ both participatory and non-participatory techniques, including hands-on cash processing, informal conversations and brief interviews with colleagues, as well as the analysis of internal organisational documents, such as operational guidelines and the cash centre manual. Each day the researcher took detailed notes. During the field research he worked across all key positions within the cash handling centre: (1) cash acceptor (cash sluice), (2) cash counter, (3) coin processor, (4) operator of cash cassettes from ATMs and (5) treasurer. A process map was prepared for each operational role.

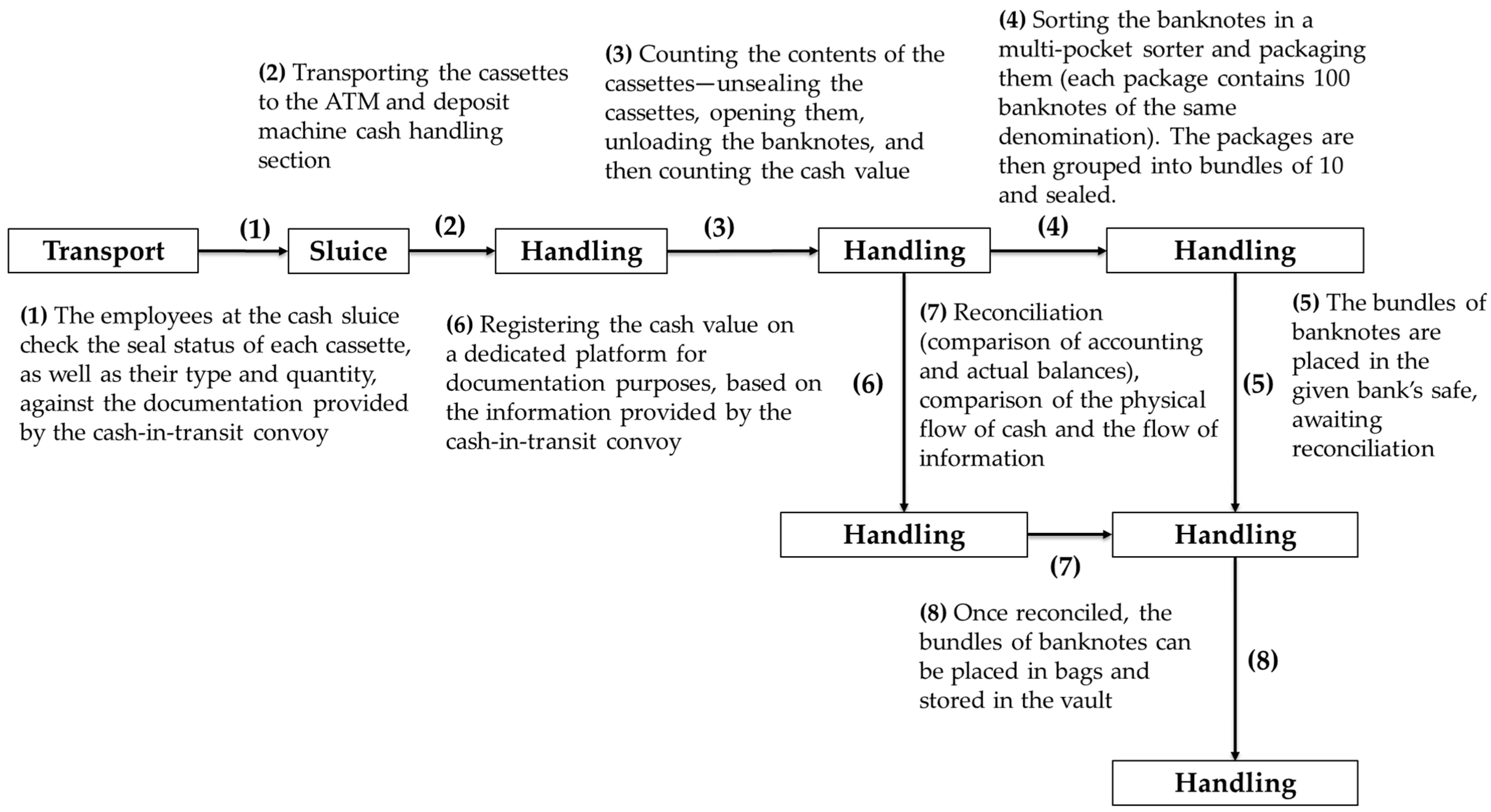

As an example, we present one of the key roles—the cash centre’s operator of cash cassettes used in ATMs and cash deposit machines. This is a complex position encompassing a range of tasks, including the following:

Unloading and loading cash cassettes used in ATMs and cash deposit machines;

Counting, sorting and packing cash retrieved from these cassettes;

Recording cash values after counting;

Reconciling cash balances.

ATM and cash deposit machine cassettes are owned by banks or ATM deployers. A cash handling centre, under an agreement with such an entity, is responsible for operating the cash cassettes—including loading, unloading and counting the cash they contain. During the time the cassettes are in use by the centre, the cash handling centre assumes responsibility for them.

The proper handling of an ATM requires two sets of cassettes—one set is placed inside the ATM, while the other remains at the cash handling centre. The ATM is programmed to recognise the cassette itself, rather than the denomination of the cash it dispenses. ATMs also contain reject cassettes, a special type of cassette where banknotes are deposited if they are (1) of suspicious quality, (2) damaged, or (3) counterfeit.

In addition to servicing ATMs and deposit machines, within this process employees also handle cash cassettes from recyclers, which combine the functions of both ATMs and deposit machines in a single device (a recycler can be used simultaneously for depositing and dispensing cash). Notwithstanding the service rendered at the cash centre, the use of recyclers enhances local cash circulation by bypassing the central bank and reducing the amount of cash transported with cash cassettes.

Figure 2 presents a process map for handling cash from ATMs, outlining eight key subprocesses involved. Initially, cash cassettes from cash dispensers, cash deposit machines and recyclers are received at the cash sluice. Employees at the cash sluice check the seals and confirm the number and type of cassettes against the documentation provided by the cash-in-transit convoy. If everything is correct, the cassettes are transported for counting. The processes at a station responsible for handling cash cassettes from ATMs and deposit machines are carried out by a single team of employees. After receiving the cassettes from the cash sluice, they are unsealed, opened, and unloaded (the cassettes in Poland may contain three main currencies: PLN, USD and EUR). Next, the cash within the cassettes is counted using a currency counter; then, the banknotes are sorted using a multi-pocket sorter, and they are packaged and bundled. Simultaneously with the cash counting (handling the physical flow), the cash is electronically registered in the accounting information system (handling the information flow). The register is based on the documentation provided by the cash-in-transport convoy. A penalty may be imposed for any errors during the recording of cash values in the cash registration system. The cash is then reconciled, meaning the accounting balance is compared with the actual physical cash at stock. If the reconciliation is successful, the cash is transported to the vault.

In the second stage of this empirical research, companies within the cash supply chain, along with a few large retailers directly involved in the cash handling process, completed questionnaires addressing key issues of paramount importance for managing the cash system.

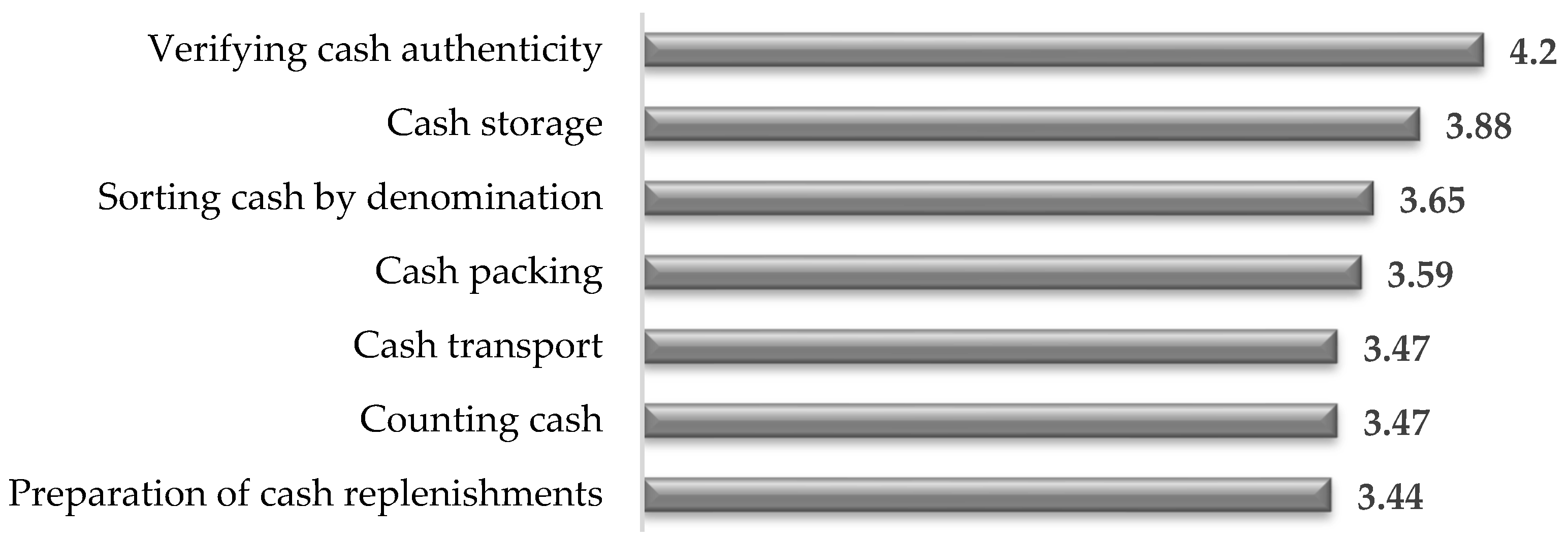

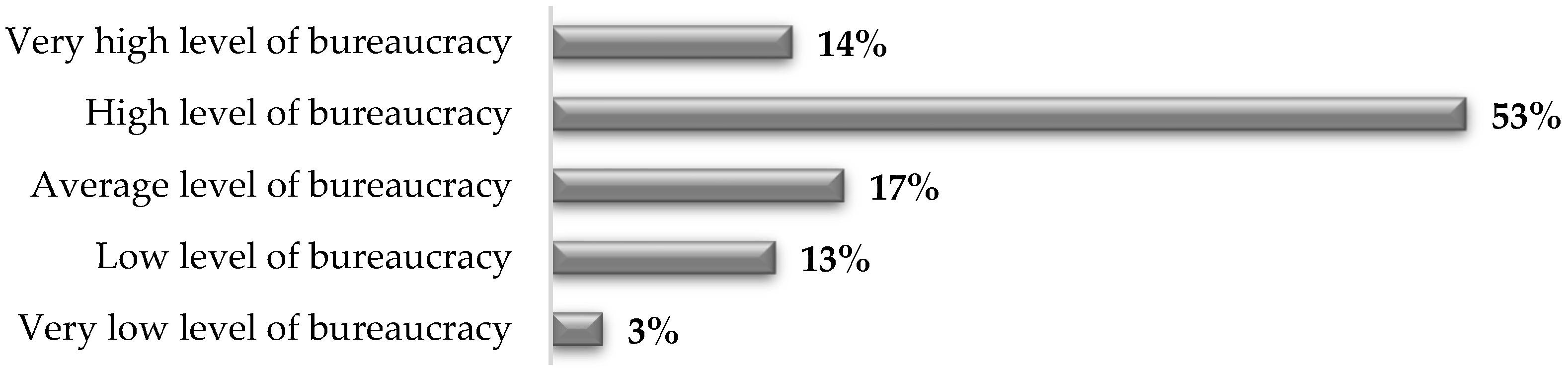

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 depict some of the responses further elaborated upon in the survey, supported by corroborating evidence gathered through participatory research at the cash centre (interviews, shadowing and document analysis).

While the standardisation of logistical processes in cash handling companies was above average according to the Likert scale, it remained relatively low considering the highly standardised nature of logistics in the cash supply chain. Cash handling involves both manual tasks and machine support, such as counters and sorters, while also ensuring synchronisation with the information flow. However, the information flow within the cash handling industry is not standardised. This includes the use of non-standardised, paper-based bank deposit slips, as well as varying standards and electronic information systems for recording cash values. Competing cash handling companies do not share information with each other, even in areas where data exchange regarding cash stocks and flows would be beneficial for all parties involved.

The survey results confirmed a high level of bureaucracy burden within the cash cycle. Participants involved in the cash supply chain in Poland associated this bureaucracy burden with numerous tasks—often manual in nature—that had to be carried out in compliance with either external legal requirements (such as those issued by Narodowy Bank Polski) or internal company regulations.

Additionally, respondents believed that the high level of bureaucracy burden can be mitigated through the widespread implementation of automated technological lines (57% of responses), the introduction of a uniform bank deposit slip standard with the option of using graphic code systems (57%), increased standardisation of processes (50%) and the creation of a single IT platform for all participants in the supply chain to be used for recording cash values (43%). Interestingly, although actors in the cash supply chain may have recognised that a single platform could serve as a valuable tool for the entire industry—particularly for cash handling companies—they appeared to distrust one another due to competitive concerns, which likely posed a significant obstacle to jointly developing such a solution.

The survey participants held divergent views on the length and structure of the cash supply chain. Some adopted a more holistic perspective, recognising the roles of all actors in the chain—including entities responsible for minting coins and printing banknotes—while others focused solely on their direct partnerships (e.g., a commercial bank in relation to a cash handling company). This difference in perspective likely influenced their views on who is or should be the integrator, serving as the control tower within the cash logistics system. Surprisingly, many respondents identified commercial banks in this role, rather than the central bank, which would more naturally be seen as the key player—acting as the issuer of cash, rule setter, coordinator and overseer of the system.

Most respondents agreed that the quality of the cash system in Poland has improved over the years, attributing this to enhanced dialogue between the central bank and the industry, technological progress and gradual investment in infrastructure—including ATMs and cash recyclers. At the same time, they pointed to ongoing challenges, such as the need for greater process automation, simplification of tasks and increasing wage pressure.

5. 4P Cash Logistics Management Model

Our empirical research allowed us to draw several conclusions relevant for designing the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model and defining its practical implications. Institutions within the cash supply chain differ in terms of

The level of standardisation of cash logistics processes;

The level of bureaucracy burden;

The accuracy of information flow within the organisation;

The information systems used for cash handling.

The cash circulation system can be split into two levels: micro and macro. At the micro level, banks, ATM operators and cash handling companies manage their cash logistics by directly interacting with consumers and merchants. The macro level concerns the management of wholesale cash handling. This management is indirect—the central bank and the state, through its legal acts, indirectly impact and macro-manage the cash circulation system.

The model takes the descriptive-graphic form. The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model depicted in

Figure 5 embraces the following:

Banknotes and coins (1P—Products);

Organisations (entities) in the cash supply chain (2P—Players);

Cash logistics processes (3P—Processes);

Regulations governing the cash circulation system (4P—Policies).

The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model highlights the central bank’s pivotal role as the cash supply chain integrator, functioning as a control tower with the objective of streamlining cash logistics processes across the entire chain. However, the central bank primarily manages the chain indirectly, exercising the authority conferred upon it by law as the issuer of legal tender. The central bank’s internal regulations on cash processing complement the external legal acts enacted by parliament and ministries (collectively referred to as policies). It is important to emphasise that the central bank is also bound by specific laws, such as the constitution or its own statute. Consequently, the arrow in the diagram is two-sided.

The central bank simultaneously acts as both a regulator of the cash system and its central participant. Therefore, regardless of the jurisdiction and the varying levels of authority granted to it, the central bank is uniquely positioned to serve as the cash supply chain integrator and operate as a control tower within the cash management system. In this role, primarily via the Policies channel, the central bank influences all aspects of cash logistics—Product (banknotes and coins), Processes (covering all cash logistics, including security) and Players (all other organisations within the cash supply chain). In Poland, the central bank does not act as a supervisor of banks; therefore, its management of the cash supply chain is indirect. Moreover, it can only issue regulations binding on banks and, via them only, on private cash handling companies. Cash logistics processes are largely operated by commercial organisations that specialise in cash handling logistics—these are companies from the non-financial sector contracted by banks.

The Product—banknotes and coins—is, on one hand, legal tender, and on the other, a physical medium whose logistic flow needs to be properly managed. It often represents substantial stocks of cash that must be securely transported, replenished in cash branches and ATMs, sorted, packed and checked for fitness.

The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model should be understood in the context of the cash supply chain, the cash circulation path and the closed-loop nature of cash circulation within the country under study.

With regard to the cash circulation path, it is essential to address specific questions such as the following:

Where does the cash circulation path begin and end?

Which entities (organisations) are involved along this path?

What logistics processes take place within each entity?

Who owns and carries out the various cash logistics processes?

Only after addressing these questions and characterising the cash logistics processes carried out by the organisations within the cash supply chain does it become possible to identify the steps needed to improve the management and functioning of a given cash circulation system.

Frequently, a refinement in the system leads to double-edged consequences. A benefit for one organisation in the chain may become a disadvantage for another. For example, eliminating mixed deposits is beneficial for cash handling companies (as it reduces the labour intensity and speeds up the counting process; it also allows processing capacity to be used for other operations) as well as for central banks (by extending the lifespan of banknotes, especially those of lower denominations, and reducing costs related to transporting and destroying unfit banknotes). However, eliminating mixed deposits is disadvantageous for retailers, as from their perspective, it prolongs the counting process and increases costs (they must now pack banknotes and coins into separate secure envelopes and acquire a larger quantity of such envelopes). In

Section 6 below, using the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model, we outline the double-edged consequences of the proposed refinements to the cash circulation system.

Before proceeding in this manner, we will first describe each of the four components of the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model, benchmarking to the examined Polish case.

Physical cash is, on one hand, legal tender and a means of payment, but on the other, it is a unique type of product. Banknotes and coins as a product can be characterised by the way they are packed for transport and storage. This packaging follows international standards and complies with central bank regulations (as depicted in

Figure 6).

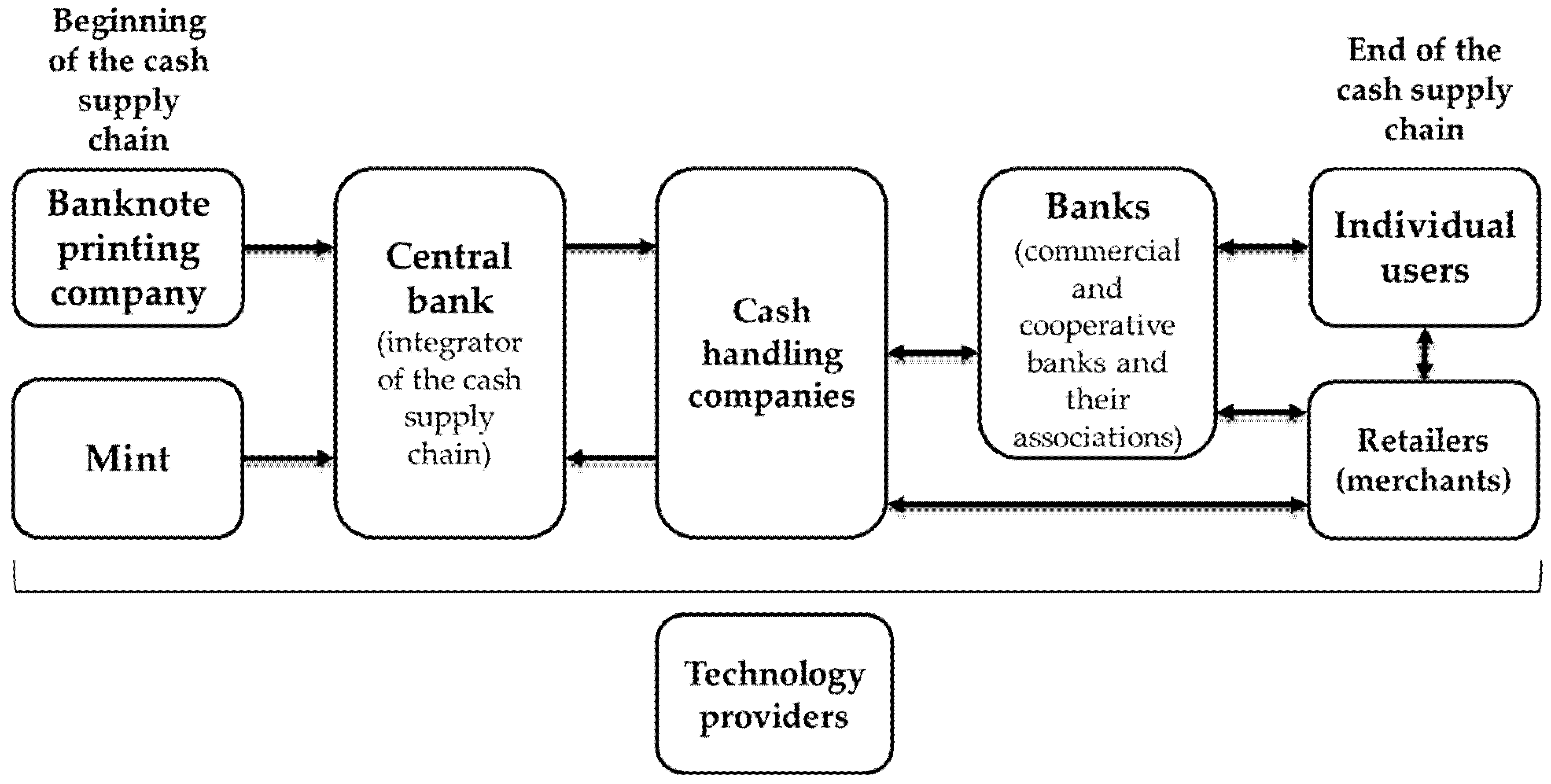

A structured diagram presenting the stakeholders (Players) in the cash supply chain, alongside a country-agnostic cash circulation path, is shown in

Figure 7.

The cash circulation path typically involves six key players: the printing and minting entities (which may include more than one, as in Poland), the central bank, cash handling companies, banks (both commercial banks and cooperative banks and their associations), end users (consumers and businesses) and merchants (including large retail stores). Additionally, technology providers are responsible for supplying solutions that streamline and automate the logistics processes within organisations across the cash supply chain. Physical cash moves back and forth along the cash circulation path within the system.

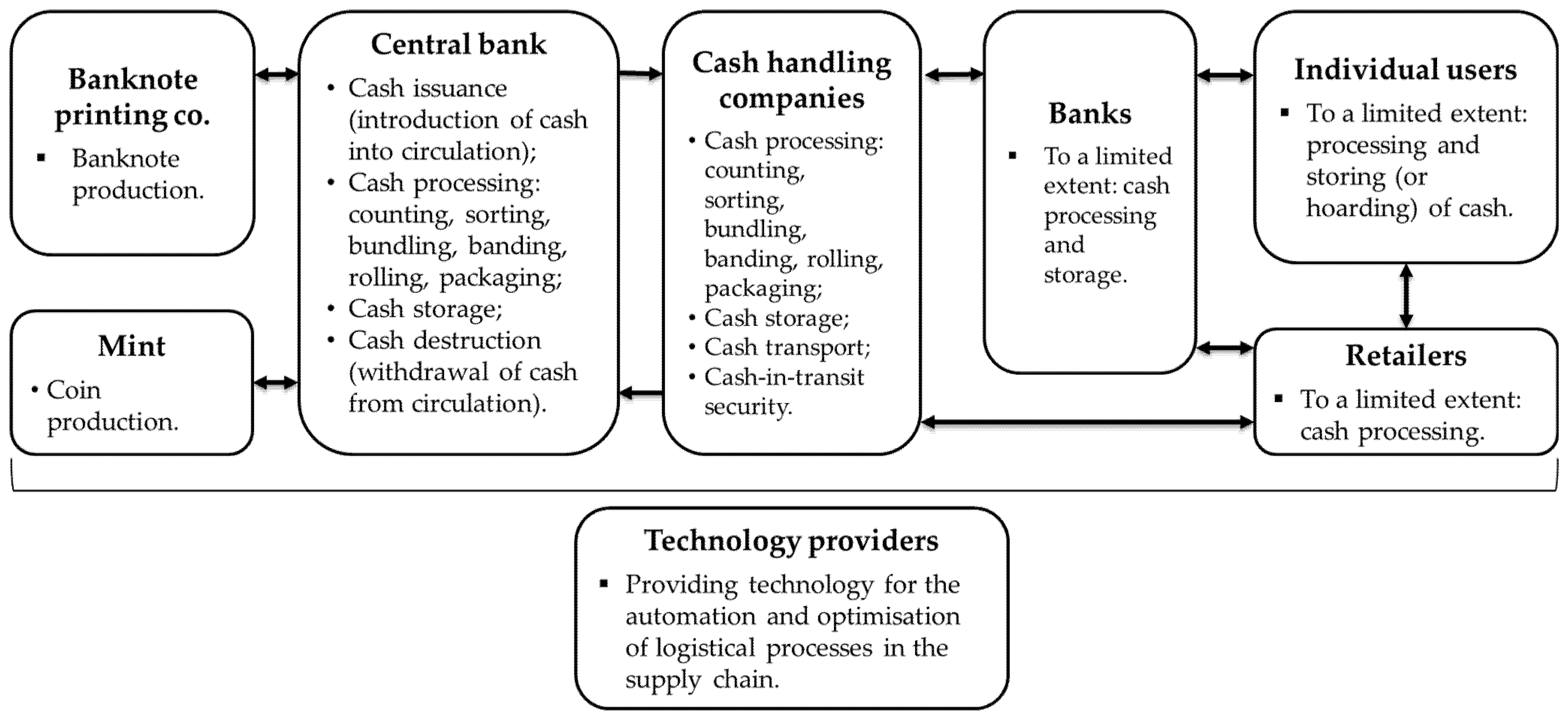

By incorporating the functions performed by each player, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of the processes occurring within the cash system (

Figure 8).

Players in the country’s cash supply chain differ in the extent of their involvement in cash processing activities, depending on the cash management model in place—whether more centralised or more delegated (see cash cycle management models in

Section 2). Typically, the central bank and cash handling companies perform the majority of cash processing. Increasingly, banks are outsourcing cash processing as part of their cost optimisation strategies.

Retailers (merchants) process cash to a limited extent—counting it at their retail outlets, sorting it and packing it into secure envelopes. They also use deposit machines (cash recyclers and back-office deposit machines). Individual customers count and sort cash and store (hoard) part of it.

Technology providers act as an external player in the cash supply chain, delivering technology and expertise to streamline and automate the logistics processes within the various entities in the cash supply chain. This includes implementing automated processing lines in cash handling centres, supplying self-service devices for branch banking and providing deposit machines for retail clients.

The cash circulation path is a closed loop. Individual customers purchase goods and services from merchants using cash, which is then transferred by merchants to commercial cash handling centres. At these centres, the cash is processed (counted, sorted, and packaged) and stored. A portion of the cash flow returns to the central bank branches, including banknotes and coins that, due to their level of wear, are no longer suitable for further circulation. Cash that is heavily worn is destroyed by the central banks. Subsequently, “old” cash, together with newly issued banknotes and coins, is once again sent to commercial cash handling centres and commercial banks.

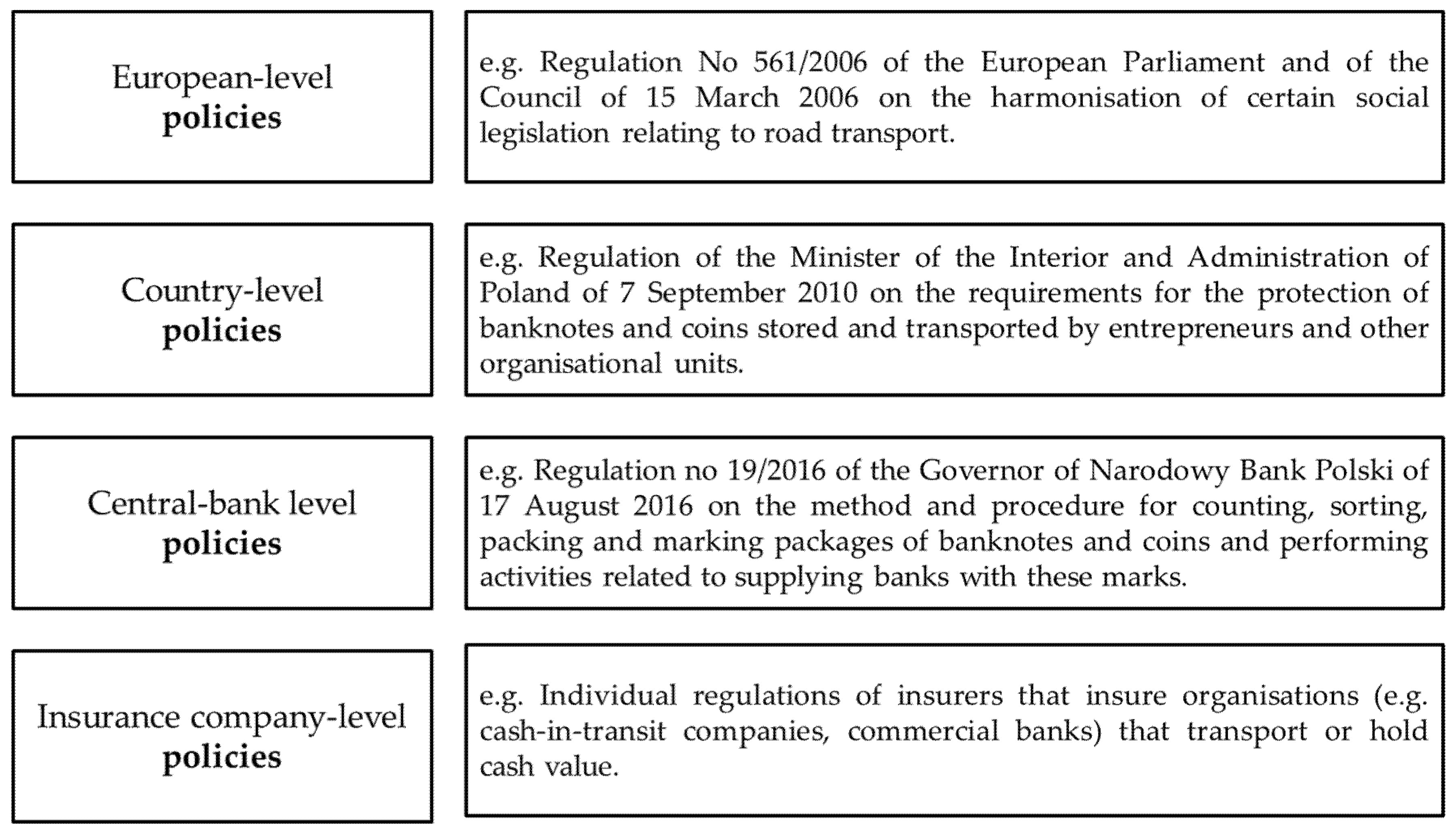

Each country’s cash system operates under specific policies that govern and regulate its cash-related processes.

Figure 9 shows exemplary policies relevant to the EU market.

The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model positions the central bank as the system integrator and control tower. Through its policies—complementary to national legislation—it can effectively enhance logistics processes across the cash supply chain.

6. Refinements to Cash Logistics

Drawing on our empirical study of the cash market in Poland (see above), we propose a series of refinements that could enhance cash logistics in various countries worldwide, thereby making our recommendations more universally applicable. These include the following:

The introduction of the private banknote deposit system.

The standardisation and electronification of the bank deposit slip using graphic codes (barcodes or QR codes).

The creation of a platform for exchanging information on cash stocks and flows and for trading monetary value between banks and cash handling companies.

The elimination of mixed deposits.

We will focus in more detail on the two central refinements (2 and 3), analysing their impact on all participants in the cash cycle, followed by an assessment using the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model. To our knowledge, the second refinement is relatively easier to implement, whereas the third represents a significant innovation that has not yet been adopted anywhere.

Regarding item 1, private banknote deposit systems—including variants such as the Notes-Held-To-Order (NHTO) system [

39]—have already been implemented in several countries. Under such arrangements, cash stocks are held in the private cash centres of banks or professional cash handlers, while legal ownership typically remains with the central bank. When needed, the physical cash can be swiftly transferred, with ownership simultaneously passed to a commercial bank (or a contracted cash handling company). This mechanism reduces the financial burden of holding cash inventories, promotes wholesale recirculation and limits the operational involvement of the central bank.

Regarding item 4, mixed deposits increase the operational costs for cash handling companies. They impede the automation of cash logistics processes, as counting such deposits is both time-consuming and labour-intensive, requiring cash centre staff to manually separate banknotes and coins. On the other hand, reflecting the double-edged consequences of such adjustments discussed earlier, eliminating mixed deposits would place a greater burden on merchants, who would be required to pre-sort banknotes and coins into stacks and rolls themselves. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it is challenging to change the behaviour of some merchants in this regard.

Let us now take a closer look at the second proposed refinement to cash logistics. The bank deposit slip is a key information carrier within the Polish cash supply chain, serving as the basis for recording the value of cash in the accounts of individual banks. However, in the current system, it is not standardised—there is no uniform physical template used across all banks. This lack of standardisation was identified by survey respondents as a significant inefficiency. The use of varying deposit slip formats complicates procedures at cash handling centres, resulting in inconsistencies in cash recording and increasing the risk of manual errors. Furthermore, the process imposes an unnecessary bureaucratic burden, as three copies of each deposit slip are produced: one for the retail client (a merchant), one for the transport service and one for the cash handling centre, where it forms the basis for accounting records. Introducing a single standardised bank deposit slip would help streamline operations and reduce costs throughout the entire cash supply chain. Moreover, additional efficiency gains could be achieved by implementing the bank deposit slip in a fully electronic format, with information exchanged via standardised graphic codes (such as barcodes or QR codes) placed on secure envelopes and bags of cash used by banks and merchants.

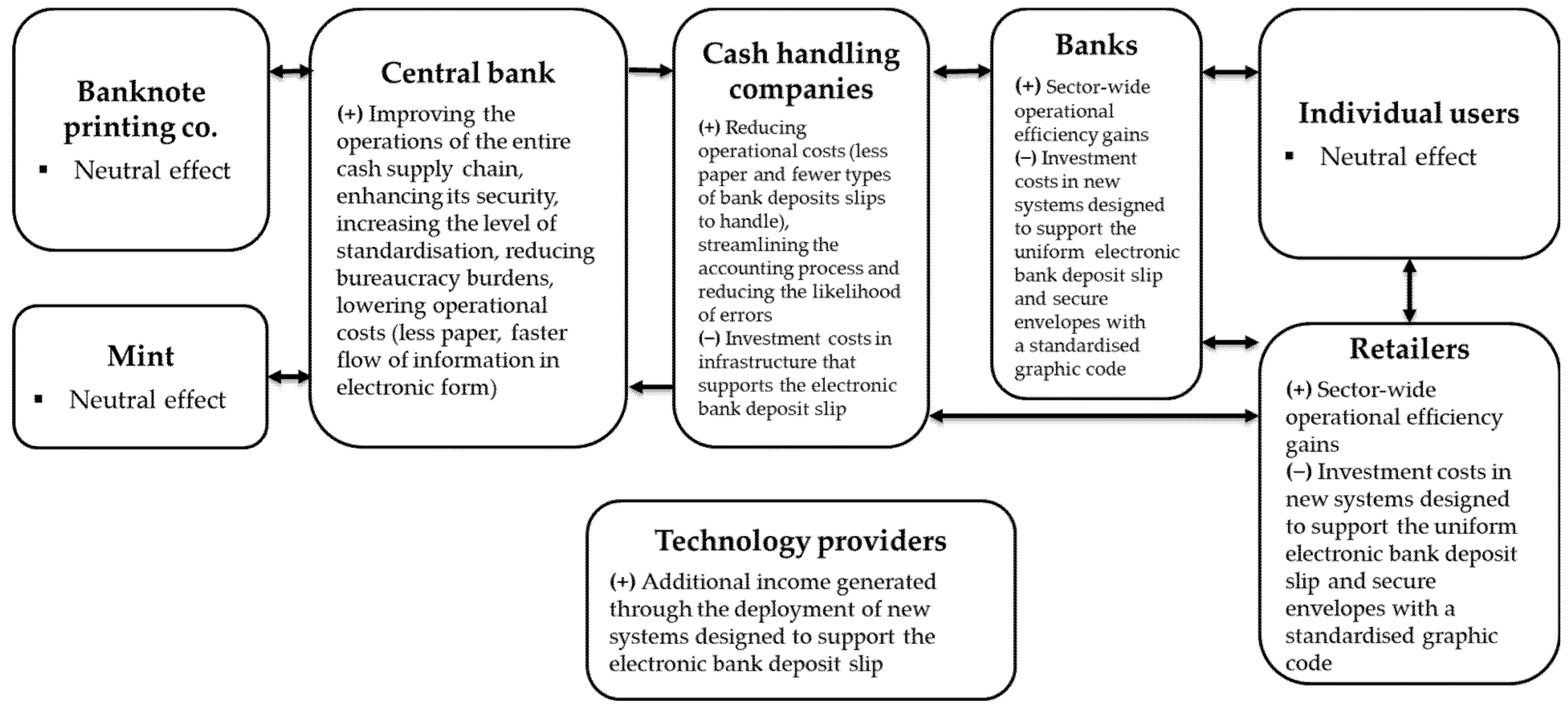

Figure 10 illustrates the impact of introducing a standardised electronic bank deposit slip, using a graphic code, on the various participants in the cash cycle.

The introduction of a uniform electronic bank deposit slip and a graphic code system would improve the reconciliation process and flow of information across the entire cash supply chain, leading to a reduction in long-term costs. Replacing paper documents with electronic ones would eliminate manual errors in cash reconciliation and strengthen the overall security of the cash handling process.

While this refinement would have a neutral impact on individual cash users, the banknote printing works and the mint, it would significantly affect other stakeholders. The main beneficiaries would be central banks and cash handling companies, as well as technology providers that could supply the necessary infrastructure upgrades.

The adoption of a standardised electronic bank deposit slip would generate sector-wide efficiency gains for banks and merchants. However, it would require initial investment in infrastructure and technology, including information systems, graphic code scanners and secure envelopes. Cash handling companies would also need to upgrade their systems accordingly. Despite the upfront costs, the investment would pay off in the long term, allowing surplus processing capacity to be redeployed to other tasks.

Nonetheless, this improvement is not straightforward to implement. From the perspective of merchants and commercial banks, the immediate benefits may appear limited, particularly in the short term. Maximum efficiency gains would be achieved if the refinement were accompanied by a fully paperless transition, including the digitalisation of cash-in-transit personnel lists.

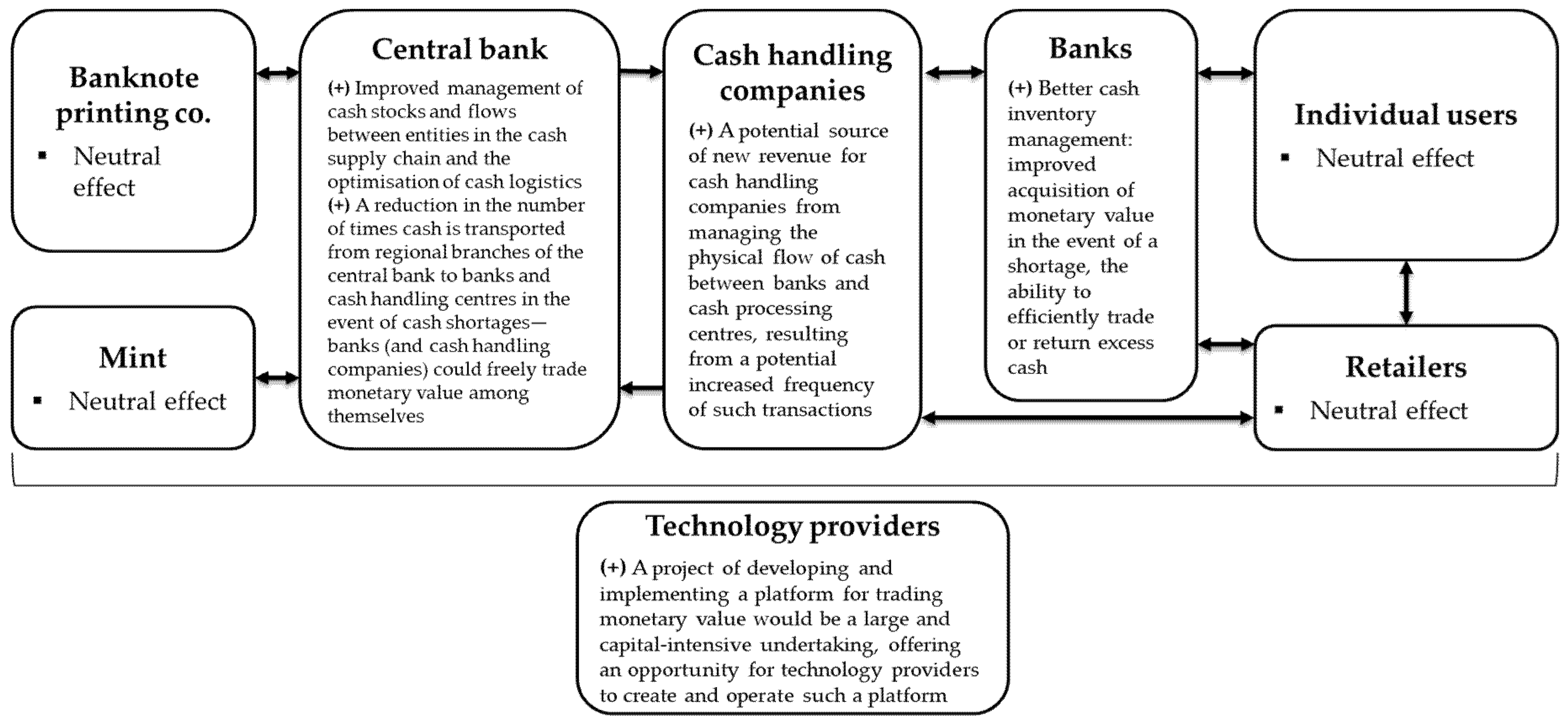

Regarding the third proposed refinement to cash logistics—namely, the establishment of a platform for exchanging information on cash stocks and flows and for the trading of monetary value between banks and cash handling companies—this would represent a significant innovation in a country’s cash circulation system. Such a major improvement would align fully with the control tower concept, as it would facilitate the efficient movement of cash based on the needs of all players in the cash supply chain. By enabling the exchange of information on cash shortages and surpluses across various locations—bank branches, cash centres and potentially ATMs—it would deliver substantial benefits across the entire industry at a national or regional level. Banks, through the use of the platform for trading monetary value, would be able to make more informed short- and long-term decisions regarding their cash holdings in cash handling centres. The online platform could integrate electronic trade between banks into a single location, enabling more efficient cash flow within the supply chain and improving communication between the chain’s entities, including the central bank and cash handling companies. Such a platform could be likened to systems used for trading unsecured interbank deposits of various tenors in the money market.

Figure 11 presents our expert assessment of its impact on the participants in the cash supply chain.

Overall, the operation of such a platform would enhance the management of cash stocks and flows across the entire cash logistics system, benefiting all participants. The central bank, as the integrator of the cash supply chain, would benefit by gaining better control over the entire cash circulation system and responding more effectively to cash demand fluctuations, including during periods of turmoil. It would likely also experience a reduction in the number of times cash is transported to and from its branches, as commercial banks could more frequently engage in multilateral physical cash exchanges among themselves.

Banks would be better informed and more capable of managing cash stocks across their various locations, such as branches and ATMs. Similarly, cash handling companies would benefit from increased revenues generated by possible higher volumes of cash being transported and processed. Technology providers could generate new income streams by supplying IT solutions to banks, cash handling companies and the central bank.

This refinement would primarily benefit the major players in the cash supply chain, while its impact on retailers, individuals and producers of physical cash would be neutral. However, in a broader context, retailers and individuals might also benefit through improved access to cash—delivered more promptly and precisely where increased demand arises.

Figure 11 omits one important factor in its impact assessment: the need for investment. As with the improved and digitised bank deposit slip system, setting up the platform would require significant resources. It is also unclear who would be best positioned to develop and operate such a platform.

The central bank is a natural candidate, given its role as the integrator of the cash supply chain and its potential to act as a control tower. However, central banks typically avoid engaging in activities that fall outside their core mandates—particularly those involving commercial functions such as the trading of cash, which would likely involve fees or interest payments between commercial banks and potentially cash handling companies. In some countries, the latter are granted a higher status and are treated more on par with banks.

An alternative scenario is that commercial banks, possibly in collaboration with cash handling companies, establish a joint venture to develop and operate the platform. While these entities are competitors in their daily operations, they could all benefit from a shared infrastructure project of this nature.

A third possibility is that a technology provider takes the lead and makes the investment. However, this would require commercial banks and cash handling companies to share sensitive operational data with a third party—something that could raise concerns around data security and governance, particularly if the third-party provider would not be subject to joint bank ownership or another formal oversight.

Once established, the platform acting in its intermediary role could sustain its operations through membership fees from founding institutions or by charging commission fees for its services.

Naturally, such a platform could operate under various configurations, offering different levels of access to shared information on cash stocks and flows. The central bank, as the issuer of cash and integrator of the cash supply chain, would likely be granted the highest level of access.

Table 2 presents the potential effects of the two key refinements examined in greater detail: the uniform electronic bank deposit slip and the platform for trading monetary value between entities within the cash supply chain. The assessment was conducted using the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model, covering all four dimensions—Product, Players, Processes and Policies—and illustrates how each would be impacted by the proposed improvements.

Since the two refinements were assessed using the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model to succinctly demonstrate their effects on each “P,” this approach could be extended to evaluate other potential modifications, such as mixed deposits, private banknote deposit systems and more.

7. Conclusions

The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model offers a structured framework for managing the cash supply chain, built around four interconnected elements:

Product;

Players;

Processes;

Policies.

As the cash supply chain integrator, the central bank—acting as a control tower—not only oversees the macro-level management of cash flows within the economy, but is also well positioned to foster innovation and increase the operational efficiency of commercial banks and cash handling companies. The model combines simplicity with practical applicability for managing cash logistics and assessing potential refinements.

In reference to the concept of sustainability, the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model can enhance this organisational parameter across four dimensions. First, Product addresses quality improvements in banknotes and coins. Second, Players concerns the costs borne by stakeholders in the cash supply chain. Third, Processes involves the operational optimisation of cash handling workflows. Fourth, Policies encompasses the development of legal frameworks that reflect market dynamics and technological advancements in cash-logistics management.

Building on empirical studies conducted in Poland and the proposed model, we advocated several refinements applicable to cash cycle management in various countries. The assessment concentrated in particular on the following:

The introduction of a standardised electronic bank deposit slip using graphic codes;

The development of a platform for exchanging information on cash stocks and flows, as well as for trading monetary value between banks and cash handling companies.

These improvements are likely to yield greater efficiency gains in countries with larger territories and less concentrated banking and cash handling markets. The first refinement has already been partly implemented in certain markets, such as Germany (GS1 standards) and India (QR codes). It is worth noting that additional refinements can be recommended (see above for examples). Any measures that promote process automation, reduce manual operations, enhance standardisation and improve the security and quality of cash circulation will ultimately increase overall efficiency across the cash supply chain and cash cycle—delivering benefits to all participants, including individuals and merchants. Numerous global examples illustrate such innovative advancements, including IoT-enabled and AI-powered recyclers that lower replenishment frequency and costs while improving fraud detection; robotic tray-fillers; and smart safes and deposit machines that provide secure storage, real-time monitoring and automated counting. These technologies would significantly support the second proposed refinement—developing a platform for exchanging information on cash stocks and flows, as well as trading monetary value.

Amid rising geopolitical tensions, several central banks—including those in Scandinavia (e.g., Norway and Sweden) and the Netherlands—are strengthening cash depot distribution, expanding geographic coverage and clarifying the roles of banks and retailers in crisis scenarios. These measures aim to ensure backup point-of-sale operations and maintain retail cash access during disruptions. As cash management grows in strategic importance, models such as the 4P Cash Logistics Management Model may offer valuable guidance. The limitations of this study stem from its focus on a single-country case (Poland). Nevertheless, the analysis was situated within a broader European and global context, which allows the conclusions to be considered broadly applicable. The empirical research employed a wide range of methods, including the analysis of legal acts and industry documents, as well as action research techniques—such as participant and non-participant observation, shadowing and a market survey of key actors in the cash supply chain.

The 4P Cash Logistics Management Model is systemic in nature and could be further enhanced by incorporating system management frameworks that detail the relationships among participants, in this particular context, in the cash supply chain, potentially including the end-user perspective. Another promising direction for future research involves the application of artificial intelligence—both to support greater automation [

40] and to analyse large datasets on cash circulation. The latter artificial intelligence application could enable the identification of patterns, improve the forecasting of cash demand and help anticipate potential shortages. In this context, processing large datasets from data silos and heterogeneous systems could benefit from models developed in the economic literature—such as the Adaptive Cloud-Based Big Data Analytics Model for sustainable supply chain management [

41].

Finally, we see strong potential for the real-life implementation of the refinements proposed in this paper. This, however, requires collaboration among market participants—banks and cash handling companies—and often a more catalytic role from the central bank, acting as the control tower and integrator of the cash supply chain.