1. Introduction

Amid the accelerating global digital transformation and heightened efforts to safeguard cultural diversity, the sustainability of cultural communication has become a critical concern shared by governments and scholars worldwide (UNESCO; The World Bank. Cities, culture, creativity: leveraging culture and creativity for sustainable urban development and inclusive growth; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–121. United Nations General Assembly. Information and communication technologies promote sustainable development. In Proceedings of the Seventy-sixth Session of the United Nations General Assembly, New York, USA, 17 December 2021). Museums, as key repositories of national cultural memory, have expanded beyond their traditional roles of artifact preservation and historical narration to become essential platforms for intergenerational transmission, public education, and international exchange. Nevertheless, conventional linear and authoritative modes of communication are increasingly inadequate in addressing the demands of a cultural landscape characterized by diversity, interactivity, and globalization [

1,

2]. This evolving context necessitates that museums reimagine their communication strategies through the lens of technological innovation, adopting models that are more dynamic, participatory, and adaptable to ensure a sustainable and evolving cultural communication ecosystem.

The rapid evolution of digital technologies, such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), artificial intelligence (AI), and digital twin systems, has significantly expanded the possibilities for cultural dissemination. These technologies have become deeply embedded in the processes of image creation, presentation, and reinterpretation, transforming images from static visual texts into interactive cultural interfaces where meaning is collaboratively constructed among users, platforms, and algorithms [

3,

4]. Consequently, images are no longer mere vessels of representation but have emerged as cognitive nodes of multisubject engagement, reshaping both the logic and mechanisms underlying cultural content production. Iconology, as a discipline focused on the interplay between images and culture, is thus undergoing a profound paradigmatic shift. Traditional “representation–interpretation” frameworks now fall short in addressing key characteristics of digital imagery, such as technological dependency, platform fluidity, and user participation [

5].

Amidst the coexistence of theoretical lag and practical complexity, the academic community has increasingly recognized the necessity of shifting image studies from a paradigm of interpretive mechanisms to one of ecological mechanisms. This transition has given rise to emerging research trajectories centered on the sustainability of digital image studies. In recent years, the field has begun to establish an embryonic theoretical framework for sustainable image practices. Zhao et al. (2023) contended that digital images function not only as technological media but also as pivotal mechanisms for the reconstruction and circulation of cultural memory [

6]. Building on this perspective, Barzaghi et al. (2024) proposed a sustainable imaging strategy grounded in the FAIR principles, viewed through the lens of digital-twin management [

7]. Similarly, Moreno et al. (2022), writing in the Journal of Cultural Heritage, introduced a 3D data lifecycle management model that provides a systematic approach to the long-term preservation of digital images [

8].

At the level of technological application, digital image studies are progressively constructing a knowledge ecosystem centered on “visual re-representation.” The works of Balletti et al. (2019) [

9], Fiorini et al. (2022) [

10], and Izaguirre et al. (2021) [

11] demonstrated the practical efficacy of photogrammetry, laser scanning integrated with GIS, and virtual engines in the reproduction and narrative dissemination of cultural heritage. In parallel, cultural participation and user collaboration have emerged as critical drivers in the theoretical evolution of the discipline. Aristidou et al. (2024) [

12], through qualitative interviews, examined the mechanisms of acquisition and preservation of VR/AR artworks, revealing how digital platforms facilitate co-creation between audiences and curators and enable the decentralization of cultural meaning-making. Boboc et al. (2022) [

13] further argued that augmented reality not only enhances accessibility but also reconfigures the cognitive structures underlying user experience. Liu (2023) [

14] highlighted that prevailing models of digital image dissemination frequently neglect the influence of cultural contextual variation on cognitive evaluation, thereby risking cultural misinterpretation and value disalignment.

International developments likewise reveal persistent structural challenges within both the theoretical and practical domains of image studies. First, there remains a lack of integrated theoretical models capable of reconciling cultural memory, platform algorithms, and user agency [

15,

16]. Second, divergent development trajectories are evident, as image strategies vary widely across regions in terms of technological logic and cultural embeddedness [

17,

18]. Third, mechanisms for cross-cultural collaboration remain underdeveloped, with inconsistent standards for resource sharing and recurrent misinterpretations of visual symbols, severely constraining the interoperability and cohesion of global cultural communication ecosystems [

19,

20]. These issues not only underscore the pressing need for a theoretical reconfiguration of image studies but also highlight the critical role of regional collaboration in facilitating a paradigmatic transformation in cultural communication.

In response to these issues, this study examines the National Museum of Korea and the Palace Museum in China as comparative case studies, chosen for their contrasting yet complementary approaches to geopolitical positioning, institutional infrastructure, and digital image strategies. As national flagship museums, both institutions play pivotal roles in the digitization and international dissemination of cultural heritage, representing broader trajectories in East Asian digital cultural governance. Yet their digital practices diverge significantly: the National Museum of Korea prioritizes immersive experiences and emotional interactivity, encouraging user agency and collaborative meaning-making, whereas the Palace Museum emphasizes structured knowledge dissemination and authoritative semantic framing, reflecting a digital communication logic rooted in cultural sovereignty [

21]. These distinctions offer a compelling foundation for comparative analysis and present a unique opportunity to identify complementary strengths in regional image-based practices.

As the transformations brought about by digital technologies, this study proposes a tripartite analytical framework for image studies grounded in the interrelated dimensions of technology, culture, and user engagement. By integrating perspectives from constructivism, cultural memory theory, and symbolic interactionism, the paper explores how digital images generate meaning, the culturally embedded logic underpinning visual content, and the participatory practices shaping user experience. Through an in-depth comparative analysis of two leading institutions—the Palace Museum in China and the National Museum of Korea—this research seeks to address the following research questions:

RQ1: In an era where digital technologies are deeply embedded in image dissemination, what specific challenges do traditional iconological theories encounter in addressing the distinctive features of digital images, such as technological dependency, platform fluidity, and user interactivity? How can these theoretical limitations be overcome by reconstructing iconology through the integrated lens of constructivism, cultural memory, and symbolic interactionism, thereby establishing a theory system attuned to the interactive logic of “technology–culture–user” in digital environments?

RQ2: What are the key differences between the Palace Museum and the National Museum of Korea in their application of digital technologies, narrative strategies, and user engagement models? Within the tripartite interactive logic of “technology–culture–user”, how do symbolic interaction mechanisms, processes of cultural memory construction, and institutional drivers exhibit distinct cultural characteristics and practical divergences in the two contexts?

RQ3: Drawing on the empirical insights from China and Korea, how can a sustainable and collaborative strategy for image dissemination be developed—one that integrates technology, enables stratified resource sharing, fosters user participation, and promotes institutional innovation? How might such a strategy facilitate the theoretical reconstruction of cross-cultural iconology and support the long-term advancement of sustainable cultural communication across the East Asian region?

2. Theoretical Lineage and Research Trends

2.1. Theoretical Evolution and the Turn Toward Sustainability in Iconology

2.1.1. Paradigm Shifts in Classical Theories and Breakthroughs in the Digital Age

The origins of iconology can be traced back to the Renaissance period, during which images were imbued with rich symbolic meanings in religious, mythological, and historical narratives. Early reflections on the relationship between images and culture, such as Giorgio Vasari’s interpretations of artistic allegories, marked the initial emergence of iconological thinking. However, iconology did not crystallize into a systematic theoretical framework until Erwin Panofsky’s seminal work, Studies in Iconology (1939), in which he introduced a tripartite model of interpretation. This model consists of pre-iconographical description, iconographical analysis, and iconological interpretation. By emphasizing the symbolic structures and value systems embedded in images within specific historical and cultural contexts, Panofsky laid the foundation for a core paradigm in image studies throughout the twentieth century [

22].

However, Panofsky’s paradigm primarily focuses on the structural interpretation of image meaning and its contextual identification, offering relatively limited attention to the dynamic vitality of images within cultural memory and their mechanisms of intermedial migration. In this regard, Aby Warburg’s concepts of “Pathosformel” (formulas of pathos) and the “Mnemosyne Atlas” provide an earlier and highly insightful theoretical alternative. By tracing how emotional expression patterns recur and transform across diverse historical contexts and media, such as painting, rituals, and astrological diagrams, Warburg revealed how images form transhistorical “chains of culture” [

23]. These chains not only possess continuity in terms of transmission but also constitute the visual structures of collective memory. His interpretation of the agency of images in historical transitions and media evolution offers a valuable theoretical foundation for understanding how visual culture may achieve sustainable transmission in the rapidly evolving technological environment of the digital age.

From the mid-to-late 20th century, iconological research began shifting from static structural analysis toward a dynamic exploration of meaning-making mechanisms. Svetlana Alpers (1983) [

24], in her work on visual culture, emphasized “the way of seeing pictures”, introducing the viewer as an active participant in the process of meaning production. This notion foreshadowed the co-creation logic of signal generation in the digital era, where “users are participants”—as exemplified by the Palace Museum’s digital artifact-tagging platform, where the public actively engages in assigning and re-encoding image semantics through interactive means. Jacques Derrida’s theory of “différance” further elucidates, from a philosophical-linguistic perspective, the processual and unstable nature of image generation. It offers critical insights into how digital images are constantly recontextualized and re-encoded through platform algorithms, interface updates, and user interactions [

25]. For example, in the “Jingtian Temple Pagoda AR Project”, user gestures trigger multiple narrative paths, concretely embodying “différance” in the dissemination of visual symbols. Likewise, André Malraux’s concept of the “Museum Without Walls” critiques the physical constraints and institutional monopolies of traditional art dissemination, envisioning a future in which images circulate freely across geographical and cultural boundaries [

26].

With the advent of the digital age, Lev Manovich’s The Language of New Media* introduced the concept of “digital iconology”, fundamentally overturning the static paradigms of traditional art history. He argued that images must be re-examined within a media ecology shaped by the interplay of data structures, platform algorithms, and user behavior [

27]. This theoretical turn complements classical iconological theories across three key dimensions.

On the “cultural memory” dimension, Manovich’s focus on cross-platform image iteration echoes Aby Warburg’s theory of the “Mnemosyne Atlas”, which emphasized the transhistorical transmission of visual symbols. For example, on TikTok, the creative remaking of Dunhuang murals continues the gestural prototypes of Buddhist iconography.

On the “user participation” dimension, Manovich’s emphasis on interactive behavior extends Svetlana Alpers’ theory of “the way of seeing”, which foregrounds the agency of the viewer. A salient example is the Palace Museum’s digital artifact-tagging platform, where the public actively assigns contemporary meanings, such as tagging “imperial pets” to historical images.

On the “institutional dissemination” dimension, his analysis of algorithmic logic advances André Malraux’s vision of the “museum without walls”, imagining the dematerialization of art. Platforms like Google Arts & Culture realize this vision by digitally aggregating global museum collections, enabling images to circulate freely across national and cultural boundaries.

As digital image circulation intensifies, so do the characteristics of replicability and disembedding, thereby reactivating Walter Benjamin’s notion of the “aura’s decay” [

28]. The rise of AI-generated imagery, which deconstructs the authority of the original artwork, underscores the enduring relevance—and complementarity—of Warburg’s cultural memory, Alpers’ subject-centered participation, and Malraux’s institutional critique. Only through a tripartite framework—technological reproduction of cultural archetypes (memory layer), negotiated meaning-making through user participation (engagement layer), and ethical regulation of algorithmic dissemination (institutional layer)—can we reconstruct the cultural sustainability of digital images in a post-auratic condition.

2.1.2. Iconological Sustainability: Conceptual Construction and a Three-Dimensional Analytical Framework

The aforementioned theoretical developments indicate a clear evolution in iconology—from Panofsky’s static structural analysis to Manovich’s investigation of digital media ecologies. The trajectory spans Alpers’ focus on the viewing subject, Derrida’s exposition of the image’s dynamic and unstable nature, Malraux’s critique of the institutional constraints of traditional art dissemination through his “museum without walls”, and Warburg’s insights into the transhistorical cultural chains forged by images. While each of these theories offers valuable contributions, they remain insufficiently integrated in addressing the complex challenges posed by AI-generated imagery, platform algorithms, and the accelerated mediation of digital culture.

Specifically, existing frameworks often fall short in reconciling the dynamic transmission of cultural memory, the mechanisms of user participation, and the ethical-institutional dimensions of image governance in the digital age. In response to these gaps, this study proposes the concept of “iconological sustainability”, which aims to provide a systematic theoretical response to contemporary image studies by constructing a three-dimensional analytical model tailored to the needs of the digital era.

(1) Conceptual Proposition: The Theoretical Imperative for a Transformation in Digital Iconology

As visual media evolve from traditional static forms to interactive digital environments, classical iconology, centered on a “text–image” analytical paradigm, has become increasingly inadequate in explaining the complex mechanisms of digital image production, dissemination pathways, and the shifting roles of users. The image–meaning–history framework established by Warburg and Panofsky, while highlighting the historical semantics and artistic styles of images, reveals theoretical limitations in the face of real-time updates, multi-agent participation, and cross-platform circulation characteristic of digital images [

29].

Current research lacks a comprehensive theoretical model that integrates technological infrastructures, institutional regulations, and user practices to systematically account for the cultural transmission and semantic regeneration of images in digital contexts. In response, this paper proposes the concept of “Iconological Sustainability”, which addresses the challenges digital images pose across three interrelated dimensions: cultural continuity, institutional legitimacy, and participatory co-creation.

The concept is grounded in a triadic structure of technological enablement, institutional regulation, and user participation, ensuring the sustained vitality of images in cultural memory, meaning-making, and social communication processes. Theoretically, it synthesizes Jan Assmann’s (1995) [

30] theory of cultural memory, Henry Jenkins’ (2008) [

31] concept of participatory culture, and UNESCO’s (2005) [

32] framework for the protection of cultural diversity. This integrative approach aims to transcend the static semantic focus of traditional iconology and respond to the dynamic demands of the digital era.

(2) The Three-Dimensional Hierarchical Model: Structural Composition and Synergistic Operation

To systematically construct the theoretical framework of iconological sustainability, this paper proposes a three-dimensional analytical model encompassing the cultural memory transmission layer, the institutional regulation layer, and the participatory co-creation layer. The model emphasizes the dynamic interplay between these layers, centering on the evolving life structure of symbolic forms and the coupling relationships between technology, institutional mechanisms, and semantic practices.

Cultural Memory Transmission Layer: This layer focuses on the historical symbols and collective memories embedded in images, highlighting the role of digital technologies in multi-dimensional restoration of cultural heritage and the construction of intergenerational identity. As Assmann [

30] argued, cultural memory is encoded and sustained through specific “symbolic media.” In practice, the National Museum of Korea has employed VR technology to digitally restore Buddhist statues damaged during the Japanese colonial period, creating a participatory restoration environment. Similarly, the Palace Museum in Beijing uses 3D modeling to reconstruct Ming and Qing court imagery, thereby reinforcing a continuous narrative of Chinese civilization. These practices transform images into evolving “cultural energy fields.”

Institutional Regulation Layer: This layer examines how institutional frameworks regulate the production and dissemination of images, focusing on their role in visual legitimacy, ethical standards, and data governance. Drawing on UNESCO’s (2005) Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, image legitimacy must balance domestic cultural policy with international ethical standards. This includes the development of normative protocols for virtual exhibitions to ensure both communicative order and cultural authority.

Participatory Co-Creation Layer: This layer underscores the collaborative nature of meaning-making, wherein users are not passive recipients but active producers of visual semantics. Based on Jenkins’ [

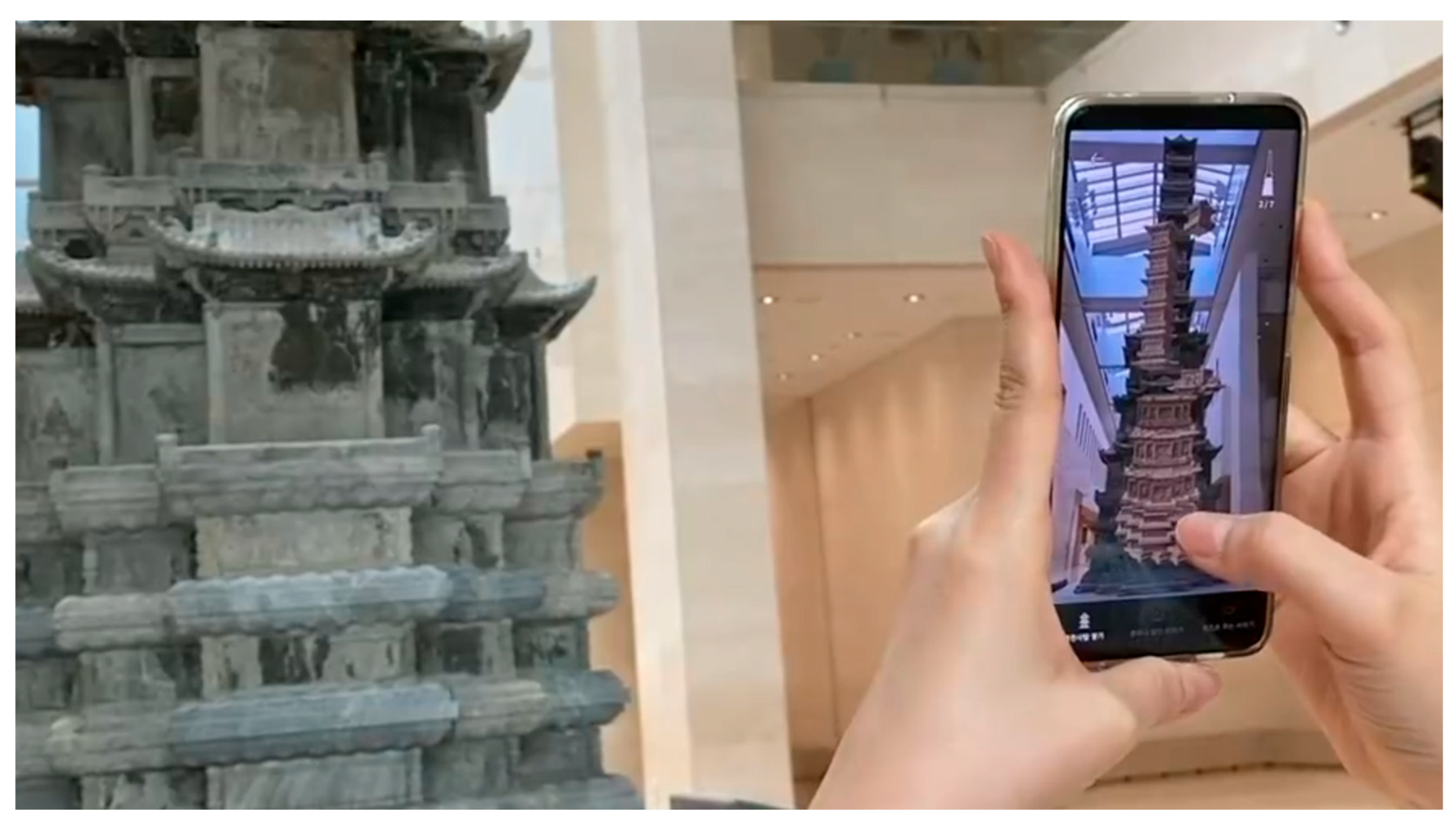

31] theory of participatory culture, users shape personalized interpretations through interactive engagement. For example, the AR Project of the Ten-Story Stone Pagoda of Gyeongcheonsa Temple in Korea activates multi-path narratives via gesture-based interaction, while the Palace Museum’s Digital Artifact Annotation Platform invites the public to contribute semantic tags. Both cases exemplify the dynamic integration of institutional authority and grassroots cultural interpretation.

(3) Coordinated Dimensional Mechanism: The Dynamic Renewal Path of Image Life

The three-dimensional hierarchical levels do not operate in isolation but constitute a coordinated mechanism throughout the image life cycle. Taking the Korean Gyeongtapsa” Ten-Story Stone Pagoda AR Project” as an example, the cultural memory dimension provides restoration demands, the institutional dimension defines restoration boundaries through ethical guidelines, and the participatory dimension allows users to generate diverse narratives. These three dimensions form a cyclical feedback loop of “memory encoding—institutional regulation—meaning co-creation”, enabling the transformation of the image from a static object into a dynamic cultural living entity.

Although China and Korea share the East Asian cultural sphere, their digital image practice paths differ. Korea’s institutional framework is more market-oriented, emphasizing cultural innovation and flexibility in user experience, whereas China focuses more on cultural security and narrative orthodoxy, reflecting the continuity of national discourse power. The complementarity between the two highlights the cross-institutional adaptability and theoretical elasticity of iconology’s sustainability.

2.2. Theoretical Pillars for the Reconstruction of Iconology: Constructivism, Cultural Memory, and Symbolic Interactionism

In the context of digital culture, the mechanisms of image production and dissemination have become increasingly technologized, platform-driven, and dynamic. This transformation presents significant challenges to traditional iconology, particularly the classical model based on the linear transmission of “image–meaning–culture”, which no longer fully accommodates the complexities of image research in the digital era. Digital images are not merely technological products; their meanings are continuously shaped by platforms, algorithms, and user behaviors. In response, this study proposes a tripartite analytical framework of “technology–culture–user”, building upon the historical transition of iconology from classical hermeneutics to digital iconology. This model is designed to better capture the pluralistic nature of image production and meaning-making in contemporary contexts.

Within this framework, technology is regarded as the foundational infrastructure of image generation. This encompasses not only the core algorithms responsible for image creation but also platform interface design, interactive media, and other digital technological tools. Together, these elements determine how images are presented and disseminated. At the same time, culture serves as the contextual dimension of images, playing an indispensable role in their creation, circulation, and interpretation. Cultural factors significantly influence the construction of meaning and the value orientation of visual content. Users, meanwhile, are no longer passive spectators, as assumed by traditional iconological models, but active participants in the meaning-making process. Their behavior patterns, feedback mechanisms, and modes of interaction directly affect the real-time interpretation of images and contribute to their continual evolution within dynamic cultural contexts.

On a theoretical level, constructivism offers a foundational framework for understanding “meaning generation” in digital iconology. Jean Piaget (1972) [

33] emphasized that knowledge acquisition is not a simple process of information transmission but is actively constructed through the interaction between individuals and their environments. This constructivist perspective has been widely adopted in digital image studies, particularly in the context of interactive image production and participatory platforms. For example, Korean scholar Choi Seongmi (2024) [

34] has explored the application of metaverse exhibitions in museums. Her research demonstrates how gamified design and virtual co-curation in metaverse environments transform audiences from passive viewers into co-creators of meaning. Audience behaviors in these virtual spaces—such as choosing narrative pathways or engaging in digital artifact restoration—directly influence the interpretation and reconstruction of images and their associated cultural symbols. These findings underscore the applicability of constructivist theory in digital iconology, especially regarding the interactive production of images and the dynamic construction of meaning.

Cultural memory theory further enhances our understanding of the role of images in the construction of historical consciousness and collective identity. Jan Assmann (1995) argued that cultural memory is transmitted across generations through images, rituals, and spatial configurations, thereby shaping collective identity. In digital museum projects across China and South Korea, images function not only as tools for information representation but also as potent cultural symbols. While conveying historical and cultural narratives, they also implicitly express ideological constructs and national identity. Thus, digital images are not static visual signs but serve as critical media for articulating national narratives and preserving collective memory.

Finally, symbolic interactionism offers a dynamic lens through which to understand the meaning-making processes of digital images. Herbert Blumer (1969) emphasized that the meanings of symbols are not fixed but are continually negotiated and redefined through social interaction [

35]. Within the framework of digital iconology, the meaning of images is not unidirectional or predetermined. Rather, it is constantly reconstructed through algorithmic recommendations, social network feedback, and user interactions. This perspective reveals a fundamental departure from the “static presentation” model of traditional iconology, illustrating how digital iconology is evolving toward a “dynamic dialogic” paradigm.

To further clarify the applicability and limitations of the three theories in digital iconology, this paper presents the following comparative

Table 1:

To further elucidate the synergistic and complementary logic of the three theoretical perspectives within the “technology–culture–user” triadic framework, this study constructs a comparative table of theoretical interaction mechanisms from a dynamic integration perspective (

Table 2). This table illustrates how the combined theories function across different dimensions through bidirectional negotiation (↔) or multidimensional layering (+).

Table 2 illustrates that the limitations inherent in any single theoretical approach can be systematically addressed through the complementary integration within the “technology–culture–user” triadic framework. This dynamic integration manifests as a structural coupling across three dimensions:

At the technological level, the combined application of constructivism, cultural memory theory, and symbolic interactionism establishes a multilayered interpretive mechanism. The dynamic feedback loop emphasized in symbolic interactionism, such as algorithmic real-time adjustment of symbolic representations, compensates for constructivism’s limited account of technological mediation. The institutional encoding emphasized in cultural memory theory, such as the standardization of metadata, sets cultural boundaries for technological applications, mitigating the risk of semantic fragmentation often associated with symbolic interactionism. Meanwhile, constructivism’s emphasis on cognitive adaptation, such as users’ active decoding of content, facilitates the transformation of technology from a neutral tool into a cognitive intermediary, thereby overcoming the static heritage bias in cultural memory theory. Collectively, these perspectives reveal that technology is neither a purely neutral instrument nor a wholly culturally determined object; instead, it emerges as a bidirectional “encoding–feedback” mediating system.

At the cultural level, the bidirectional negotiation between constructivism and symbolic interactionism, such as users’ deconstruction of authoritative narratives, and the tension-balancing between cultural memory theory and constructivism, such as the pre-setting of historical contexts, jointly realizes a dialectical unity of cultural innovation and identity. While symbolic interactionism fosters the open negotiation of cultural meanings, cultural memory theory imposes institutional constraints to prevent excessive deconstruction. As a result, cultural memory is neither a rigid, authoritative narrative nor a chaotic flow of meaning, but rather a dynamically reproduced system that preserves core cultural elements.

At the user level, the layered complementarity among the three theories dissolves the traditional dichotomy between the individual and the collective. Constructivism empowers individuals, e.g., through low-threshold interactive design, activating micro-level user behaviors and addressing cultural memory theory’s neglect of agency. Symbolic interactionism fosters communal meaning-making—e.g., through interactions on social media platforms—thus transcending the isolated cognitive stance of constructivism. Cultural memory theory elevates individual experiences into collective memory—e.g., through ritualized VR experiences—mitigating the risk of semantic nihilism in symbolic interactionism. Users thus become layered co-creators across “individual exploration–community negotiation–collective identification”, and their evolving roles provide robust empirical support for the explanatory power of the triadic framework.

In conclusion, within the theoretical framework of digital iconology, constructivism, symbolic interactionism, and cultural memory theory offer complementary perspectives for understanding how image meanings are continuously generated and transformed through the interplay of technology, culture, and users in the digital age. Symbolic interactionism highlights the meaning-making process between users and platforms; constructivism emphasizes user agency in actively generating meaning through interaction; and cultural memory theory underscores the role of images in shaping collective memory, national identity, and historical narratives. The integration of these perspectives not only deepens our understanding of how image meaning emerges at the intersection of technology and culture but also provides a dynamic and structurally grounded theoretical lens for digital iconology. Their application offers valuable insights and theoretical support for future research into the evolving semantics of digital images.

2.3. The Driving Logic Behind Theoretical Reconstruction: Transformations in Viewing Mechanisms and Interdisciplinary Integration

Amid the rapid surge of the digital age, iconology stands at a critical juncture of transformation. The urgency and necessity of its theoretical reconstruction are manifested across multiple, interwoven core dimensions.

2.3.1. Disruptive Changes in Image Generation and Viewing Mechanisms

With the deep penetration of digital media technologies, both the mechanisms of image generation and the ontological attributes of images have undergone fundamental transformations. These technological interventions not only reshape the structural composition of images but also redefine the processes through which meaning is generated and disseminated. Under the traditional paradigm of iconology, images were primarily grounded in physical media, their meanings relatively stable and analyzable through a linear research model—often proceeding in stages from pre-iconographic description to iconographic analysis and finally iconological interpretation. This framework emphasized historical context and symbolic content as stable reference points.

In contrast, the digital age has decoupled image generation from physical media, shifting instead toward code-based constructions. This transition renders image meaning no longer fixed but continuously evolving through audience interaction. Specifically, image production in digital environments is driven by a constellation of factors—algorithmic logic, user behavior, and platform architecture. Algorithms not only determine modes of visualization but also tailor image presentation through precise data tracking and predictive modeling, thereby rendering image interpretation increasingly personalized and dynamic. The diversity of user engagement means that meaning is no longer generated in a unidirectional flow but emerges through iterative interaction, real-time feedback, and contextual modulation based on diverse user backgrounds and needs. As such, meaning in digital imagery becomes fluid, variable, and contingent, fundamentally different from the stable semiotic structures pursued in traditional iconology.

Simultaneously, the mechanisms of image viewing have been fundamentally reconfigured. In traditional museum display contexts, viewers typically occupied a passive role, with meaning determined and transmitted largely by curatorial authority. Audience interaction was limited, and interpretation remained centralized. However, the widespread adoption of virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and other immersive technologies has redefined viewing from a passive act to an active, co-creative process. Audiences can now explore cultural symbols and narrative logics through self-directed perspectives, bodily movement, and interactive engagement. This shift represents a revolutionary departure from passive reception to participatory meaning-making, giving rise to a diversified spectrum of viewer–image relationships.

Consequently, the definition of the image object itself must transcend static conceptions and be re-envisioned as dynamic and processual. An image is no longer a fixed entity but a mutable element that evolves through technological mediation and user interaction. Within this new framework, image viewing emerges not as a simple act of observation but as a complex structure of interaction among algorithms, platforms, and users. Each component plays a vital role: audience interactions continually reshape meaning, while platform design and algorithmic operations determine how images are presented and interpreted.

In sum, the introduction of digital technologies has fundamentally disrupted both the generation and viewing mechanisms of images. These interrelated transformations constitute a central driving force behind the theoretical reconstruction of iconology and form the foundation for contemporary research in digital visual culture.

2.3.2. The Imperative of Interdisciplinary Integration and the Expansion of Knowledge Value

The multidimensional complexity and continuous evolution of digital images have rendered the traditional theoretical framework of iconology insufficient for addressing the emerging challenges posed by contemporary image practices. To adapt to these transformations, iconological theory must increasingly incorporate perspectives and methodologies from diverse disciplines such as the philosophy of technology, cognitive science, and media archaeology. This interdisciplinary integration is essential for comprehensively understanding the production, dissemination, and sociocultural implications of digital imagery.

First, the philosophy of technology offers critical analytical tools for examining the socio-political structures embedded in visual technologies. Meyer et al. (2024) argue that technological systems, including algorithms used in image generation and recognition, are not value-neutral but are deeply entangled with specific ideological and power structures [

36]. This insight shifts iconological inquiry beyond symbolic interpretation to a critical examination of the technological power mechanisms that shape how images are produced and circulated, underscoring the inextricable linkage between visual media, social structures, and power dynamics.

Second, cognitive science provides empirical support for understanding how digital images are perceived by audiences. Drawing on eye-tracking experiments and other empirical techniques, Shen et al. (2024) examined the perceptual processes involved in digital image engagement [

37]. Their findings demonstrate that digitally integrated text-image presentations enhance the efficiency of visual information processing and help sustain cognitive engagement. This evidence provides a robust foundation for designing interactive strategies and information architectures in digital museums, offering actionable insights into optimizing visual representation for improved audience cognition.

Moreover, media archaeology emphasizes the material and historical dimensions of digital images, arguing that they are not disembodied virtual entities but are instead the outcome of specific storage technologies, developmental trajectories, and historical-cultural conditions. As articulated by the Wei Tong research group at Peking University (2024), technologies such as blockchain used in digital heritage preservation highlight the temporal and material embeddedness of images [

38]. Blockchain not only reinforces the historicity and materiality of images but also offers novel solutions for securing image ownership and ensuring the transmission of cultural memory through tamper-proof digital records.

Together, these interdisciplinary engagements enable the formation of a more robust and adaptable theoretical framework for iconology. This evolving framework broadens the application scope of iconological inquiry and opens new avenues for future research. From cultural heritage preservation and AI ethics to education and artistic creation, the integration of diverse disciplinary insights ensures that digital imagery continues to develop and operate across multiple dimensions in the digital age.

2.4. Sustainable Development Pathways for Museum Digital Transformation and Cultural Communication from the Perspective of Iconology

As discussed earlier, iconological theory has evolved from Panofsky’s structuralist analysis to Warburg’s concept of the “cultural chain” and further to Manovich’s paradigm of digital image data structures. This evolution marks a shift from static semantic interpretation to a dynamic recoding mechanism that operates across platforms and media. Building on this trajectory,

Section 2.1 delineated a three-dimensional analytical model for the sustainable development of iconology, comprising a theoretical framework of “institutional structures—cultural memory—user mechanisms.” This model emphasizes that images are not merely visual symbols but interactive products shaped by institutional discipline, cultural representation, and cognitive behavior.

Section 2.2, grounded in constructivism, cultural memory theory, and symbolic interactionism, systematically constructed the foundational structure of this triadic iconological model.

Section 2.3 explored the transformation of viewing mechanisms, revealing the user’s role shift from passive recipient to active meaning-maker, thereby highlighting the cognitive inflection point within the “image–platform–subject” triadic relationship. Continuing this theoretical logic, the present section critically examines how iconology, from the perspectives of institution, image, and subject, responds to mainstream sustainable development frameworks in the context of digital museums. It further investigates cultural governance pathways for image sustainability and cross-cultural adaptation mechanisms by integrating image practices in Chinese and Korean museums.

- (1)

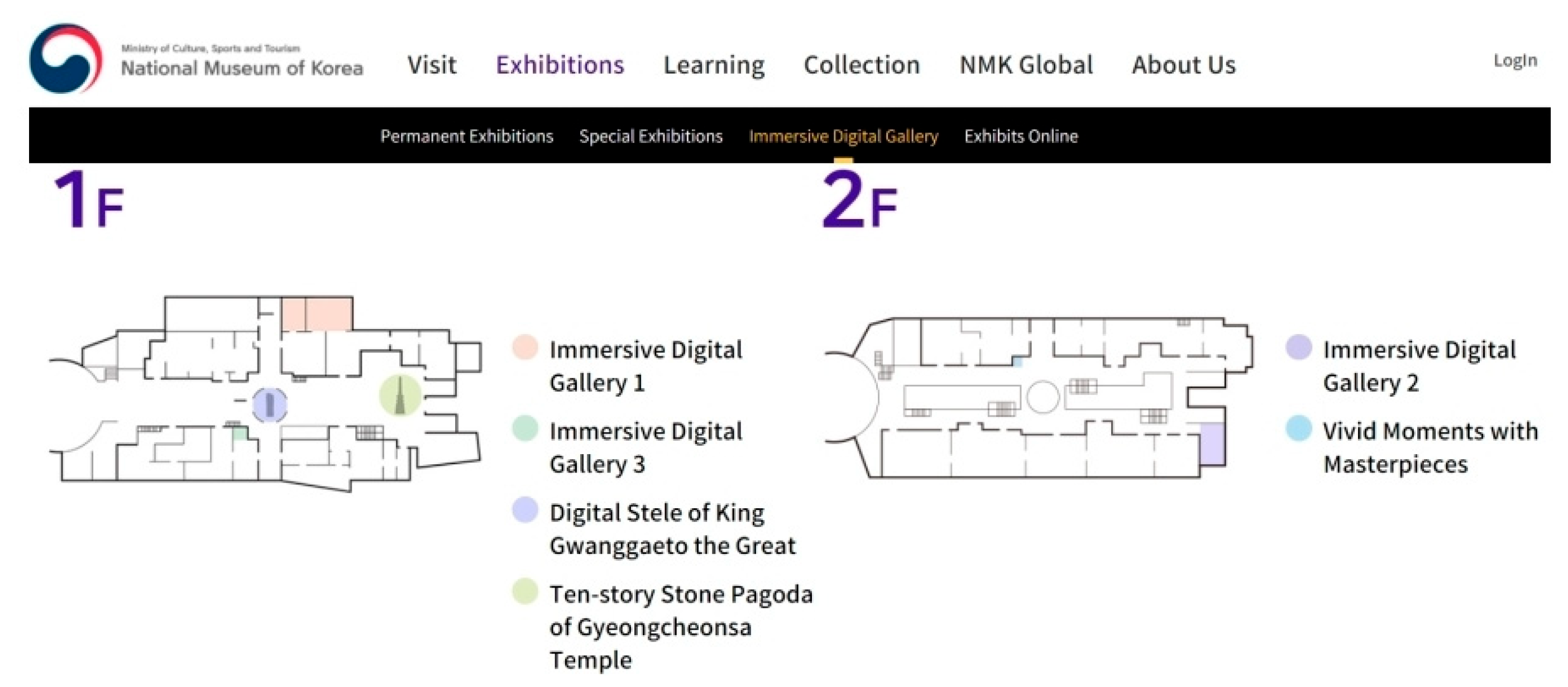

Institutional Dimension: Cultural Governance Mechanisms of Image Semantic Legitimacy

From an institutional perspective, the digitalization process of South Korean museums demonstrates a strong coupling between policy-driven initiatives and institutional innovation. Existing studies indicate that, since 2005, the South Korean government has actively promoted the development of virtual exhibition systems in national museums through financial support and policy guidance, establishing a relatively mature institutionalized path for digital transformation. A representative example of institutional innovation is the “Collaborative Tagging Mechanism” implemented by the National Museum of Korea. This mechanism encourages public participation in the construction of image semantics, concretizing cultural openness policies into a negotiated practice of meaning-making, thereby effectively translating institutional logic into a communication context [

39]. In terms of specific display strategies, this institutional flexibility is further embodied in the audience experience mechanism of the “Homo Sapiens Special Exhibition”. Zoh (2023) [

40] pointed out that this exhibition integrates Western sensory participation paradigms, forming a feedback loop between institutional design and user interaction, which significantly enhances the exhibition’s communicative efficacy and cultural adaptability.

In contrast, Chinese museums exhibit a normative logic oriented towards cultural security in their institutional designs. The Palace Museum’s digital strategy emphasizes the concept of “cultural reproduction”, constructing a “semantic hierarchical review mechanism” accordingly. This mechanism, controlled by experts, ensures continuity and consistency between digital content and the national narrative, reflecting a top-down approach to maintaining semantic legitimacy [

41]. Moreover, Wang Feng (2023) [

42] noted that Chinese digital museums commonly adopt a systematic pathway of “platform integration—data-driven—service expansion”, embedding cultural governance intentions into concrete technological processes. This pathway not only highlights a rigid demand for cultural content control but also stands in stark contrast with South Korea’s open model that emphasizes public negotiation and collaborative meaning-making within institutional frameworks.

Thus, at the institutional level, digital museums in China and South Korea demonstrate divergent governance orientations regarding image semantics: China focuses on semantic reproduction and communication stability within an “expert–state” system, whereas South Korea highlights the meaning-generation process through a “public–institution” collaborative relationship.

- (2)

Image Dimension: Visual Re-encoding Mechanisms of Cultural Memory

In the transition from institutional governance to image practice, the role of imaging technologies in the construction of cultural memory has become increasingly prominent, particularly in the digital presentation of intangible cultural heritage. For instance, the “Gowoo Dance AR Project” in Gwangju, South Korea employs motion capture and augmented reality technologies not only to enhance the immersive experience of traditional rituals but also to serve as a concrete application of the “Digital Perception Model for Intangible Cultural Heritage” proposed by Han et al. (2022) [

43]. This highlights the significant impact of digital imaging technology on the reconstruction of cultural memory. Concurrently, Kim et al. (2019) [

44] theoretically emphasized that the coupling mechanism between “technology and memory” has become a critical fulcrum for the digital transformation of intangible heritage, facilitating the sustainable dissemination of cultural heritage through modern media.

Correspondingly, Chinese digital museums emphasize a dialectical unity between visual accuracy and narrative strategy in their imaging approaches. Yan Xin (2021) [

45] pointed out that standardized technical metrics play a key role in the visual fidelity of the Palace Museum’s 3D modeling, while the “de-textualization design” strategy leverages visual cues to guide users in meaning construction, reflecting the museum’s concept of “visual guidance.” Within this framework, images are no longer mere media for information display but serve as primary carriers for meaning-making and cultural experience. Compared to South Korea’s emphasis on emotional engagement and bodily interaction, the Chinese approach achieves stable encoding of cultural symbols through high fidelity and visual coherence. Although differing in methodological focus, both approaches respond to the core demand for visualizing cultural memory.

Therefore, from the image dimension perspective, South Korea prioritizes enhancing the contextuality and interactivity of cultural experiences through technology, while China places greater emphasis on the compatibility of image precision and cultural authority. Together, these form complementary pathways for the digital reproduction of cultural memory.

- (3)

Subject Dimension: Participatory Reconstruction Pathways of Viewing Mechanisms

The application of imaging technologies ultimately requires subject participation to realize value transformation. Against the backdrop of deepening digital transformation, changes in user viewing behavior have become a crucial component in the evolution of museum communication mechanisms. Taking the “Gyeongcheonsa Stone Pagoda AR Project” in South Korea as an example, this initiative integrates gesture recognition, multi-path storytelling, and immersive technological experiences to stimulate cognitive engagement and contextual associations among users of various ages and backgrounds when interacting with traditional cultural images.

In the Chinese context, public participation is also showing a trend of continuous deepening. Wang Feng [

42] noted that the Palace Museum’s “Court Pets” project, through its social media operations and hashtag-driven dissemination, has encouraged users to actively interpret traditional images and express them in contemporary ways. This participatory model not only breaks down the authoritative boundaries of traditional images but also facilitates the semantic reconstruction of cultural resources on new media platforms. The interactivity of digital platforms has become a key mechanism for stimulating public cultural expression and aesthetic engagement.

Furthermore, cross-cultural educational cooperation mechanisms provide institutionalized and structured support for user participation. For instance, the Keio Museum Commons at Keio University, Japan (2024) [

46], proposed a “museum user co-creation mechanism” that enables diverse user groups—including university students, educators, community members, and cultural tourists—to play an active role in content production, exhibition design, and contextual translation through image literacy courses and collaborative curation projects. This mechanism promotes the transformation of viewing behavior into sustained cognitive practice. It not only establishes a closed loop between knowledge transmission and cultural experience but also offers viable pathways for institutional integration and strategic translation between Chinese and Korean museums.

Therefore, the transformation in the subject dimension is reflected in the continuous shift of user viewing behavior from a “receptive” mode to a “co-creative” and “reconstructive” mode. This evolution relies not only on technological media support but is also deeply rooted in the synergistic development of cultural mechanisms, educational systems, and platform strategies. Although China and South Korea pursue different paths, both are moving toward the shared goal of establishing museums as cultural co-creation spaces, achieving a structural reconfiguration from sites of knowledge display to platforms of multi-subject participation.

In summary, the digital practices of museums in China and South Korea, through the three-dimensional framework of “institution—image—subject”, validate the cross-cultural applicability of sustainable iconology theory. From South Korea’s semantic democratization mechanisms to China’s culturally secure semantic hierarchical review logic; from the emotional encoding technologies of the Gowoo Dance AR project to the precise modeling strategies of the digital Palace Museum, along with intergenerational user participation models, all demonstrate that only through an organic coupling of cultural memory technological reproduction, institutional normative flexibility, and layered user participatory co-creation can a sustainable system for image heritage be constructed in the digital era.

4. Collaborative Strategies for the Development of Digital Iconology in China and Korea

The preceding analysis has revealed both divergent pathways and structural complementarities in the digital iconological practices of museums in China and Korea. These heterogeneities are not limited to differences in technological choices or semantic construction; they also imply significant potential for fostering cross-cultural collaboration and co-creation of knowledge. Exploring this potential is not only conducive to forming an “East Asian visual consensus” but also provides a practical foundation for establishing mechanisms of “cross-cultural visual reconstruction.” More importantly, this process holds theoretical significance and practical relevance for enhancing the international visibility of regional cultural dissemination, as well as for facilitating a paradigmatic shift and deep transformation of iconological theory in the digital age.

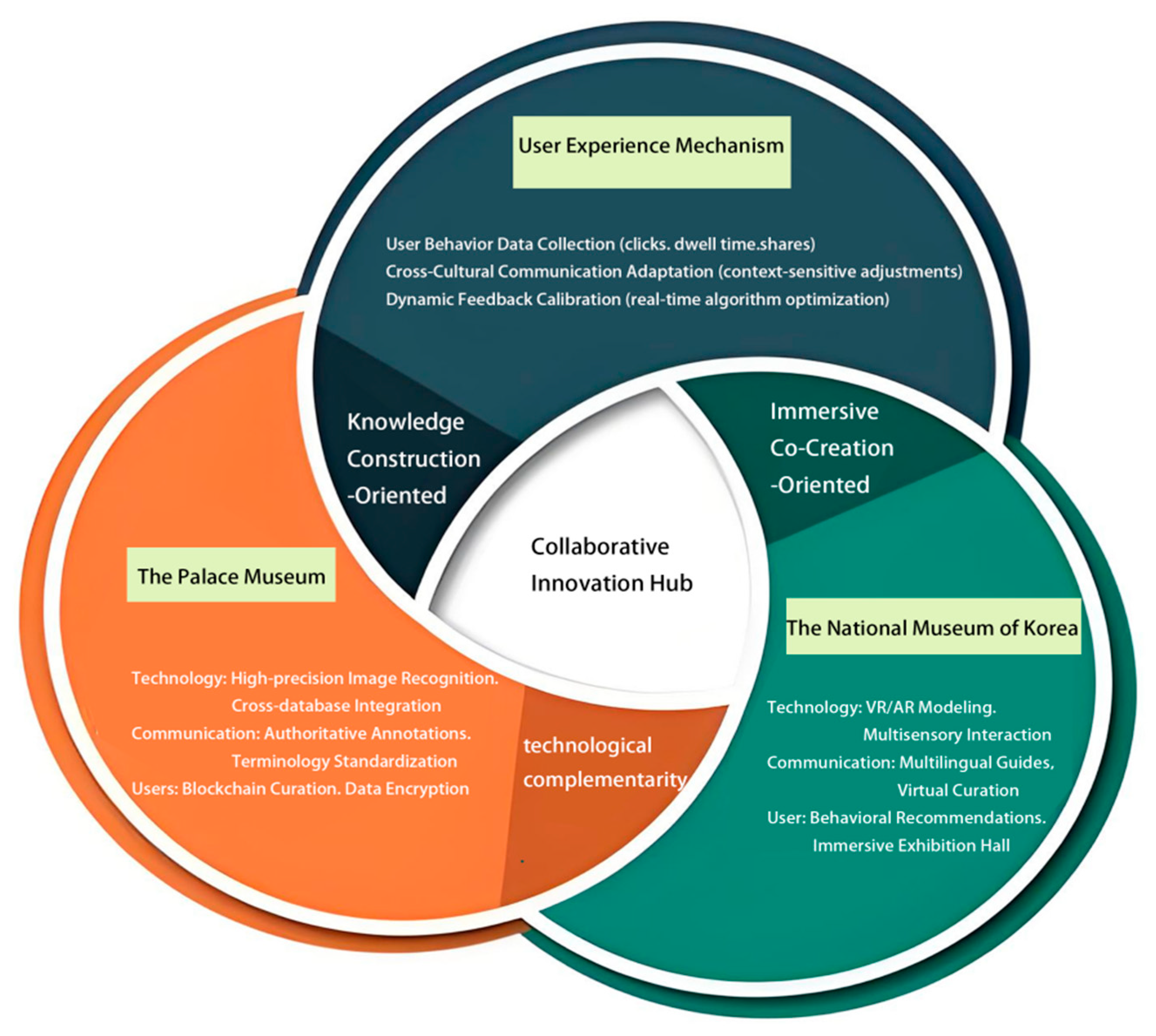

Against this backdrop, this paper proposes a set of actionable strategies for the collaborative development of digital iconology between China and Korea, structured around five key dimensions: technological integration, resource sharing, user participation, communication strategies, and cross-cultural cooperation. Grounded in the analytical foundations established above, these strategies aim to enhance both relevance and feasibility, while striving for a methodologically integrated approach that unites theoretical insight with practical orientation.

4.1. Technological Integration and the Application of Emerging Technologies

As China and Korea progressively uncover the complementary potential of their digital iconological practices, technological integration emerges as a critical entry point for collaborative development. Korea’s strengths in multimodal immersive interaction technologies—such as haptic feedback and spatial perception—combined with China’s robust foundation in AI-based semantic analysis—such as image annotation and knowledge graph construction—create favorable conditions for jointly exploring the development of a “contextual semantic enhancement system.” This system aims to deeply integrate immersive interactive experiences with semantic computing functions, thereby not only enhancing user engagement but also strengthening the knowledge linkages and cultural understanding embedded within digital images.

For instance, China’s AI semantic engine, developed by the Palace Museum, could be integrated into the National Museum of Korea’s virtual exhibition project Healing Mountains. When users interact with core exhibits such as the Pensive Bodhisattva, the system could simultaneously present a structured knowledge map tracing the evolution of Buddhist sculpture and the broader network of East Asian religious art. Conversely, Korea’s advanced spatial recognition and gesture interaction technologies could be embedded into the Palace Museum’s Digital Treasure Gallery project, allowing users to trigger detailed craft animations through hand gestures, thus enriching three-dimensional immersion and enhancing the vividness of artifact presentation. This bidirectional technological integration not only improves the richness of the user experience but also lays a technical foundation for the cross-border dissemination and semantic reconstruction of Sino-Korean cultural content.

Building on this, quantum computing—as a representative frontier technology—holds promise as a medium-to-long-term strategic engine for Sino-Korean collaboration in digital iconology. Its implementation may proceed in three stages. In the short term, both parties could jointly develop image encryption systems based on quantum hashing algorithms to strengthen copyright verification and secure cross-border circulation of cultural images. In the medium term, quantum parallelism could be used to optimize cross-modal image retrieval systems, significantly improving the efficiency of heterogeneous image matching. In the long term, the two countries could co-develop a quantum-driven cultural memory simulation system to reconstruct highly realistic historical trade scenes and cultural events, thereby enhancing the accuracy of cultural memory visualization. Existing studies provide strong evidence for the applicability of quantum technologies in related domains. For instance, Ortolano et al. (2023) demonstrated the potential of quantum-enhanced pattern recognition in handwritten digit classification [

52]. Similarly, Xu Jing (2024) explored the use of quantum information technologies in the stylistic analysis of traditional painting and proposed a quantum image enhancement algorithm that improved both the artistic creativity and the cultural value of traditional artworks [

53]. Nevertheless, as quantum computing remains in its experimental phase, it faces challenges such as algorithmic instability, high hardware costs, and long development cycles. To ensure the scientific and sustainable implementation of this long-term strategy, a feasibility evaluation mechanism should be established. Key performance indicators—such as “unit image processing cost”, “retrieval efficiency gain”, and “simulation precision error rate”—can be used to dynamically assess cost-effectiveness and guide the rational deployment of quantum technologies in this domain.

To ensure the effective implementation of the aforementioned integration strategies, it is essential to promote the establishment of a Sino-Korean Joint Laboratory for Digital Iconology involving top-tier museums and technology enterprises from both countries. This joint initiative should include three specialized working groups with distinct yet collaborative functions.

First, the Perception Technology Group, led by the Korean side, will focus on standardizing XR terminal interaction protocols, including spatial coordinate systems and gesture recognition APIs. By overcoming device compatibility barriers, this group will support the integrated deployment of immersive platforms and enhance interoperability across institutional digital image systems.

Second, the Cognitive Technology Group, led by the Chinese side, will be responsible for building a bilingual ontology database for cultural artifact semantics. This database, projected to include over 100,000 entries on cultural symbols and visual features, will be compiled using data from the Palace Museum’s digital collections, the National Museum of Korea’s digital resources, and bilateral academic platforms. A combined method of expert annotation and machine-assisted extraction will be used, with entries selected based on frequency of occurrence, cultural significance, visual distinctiveness, and semantic ambiguity. This ontology will serve as a solid foundation for cross-lingual semantic interoperability and knowledge sharing between the two nations.

Lastly, the Ethics Review Group, jointly formed by both sides, will draft the Code of Ethics for Digital Cultural Heritage Technologies. This code will address key issues such as cross-border user data flows, boundaries of image reinterpretation, and verification of authenticity in generated content. It aims to mitigate risks related to algorithmic bias and narrative manipulation, ensuring that technological innovation proceeds under the guidance of cultural respect and ethical regulation. In doing so, it will provide long-term governance support for the collaborative development of digital iconology in China and Korea.

Through this multi-tiered and multidimensional strategy of technological integration and institutional cooperation, China and Korea can deepen their existing complementarity and collectively shape a competitive East Asian narrative force amid the global wave of cultural digital transformation.

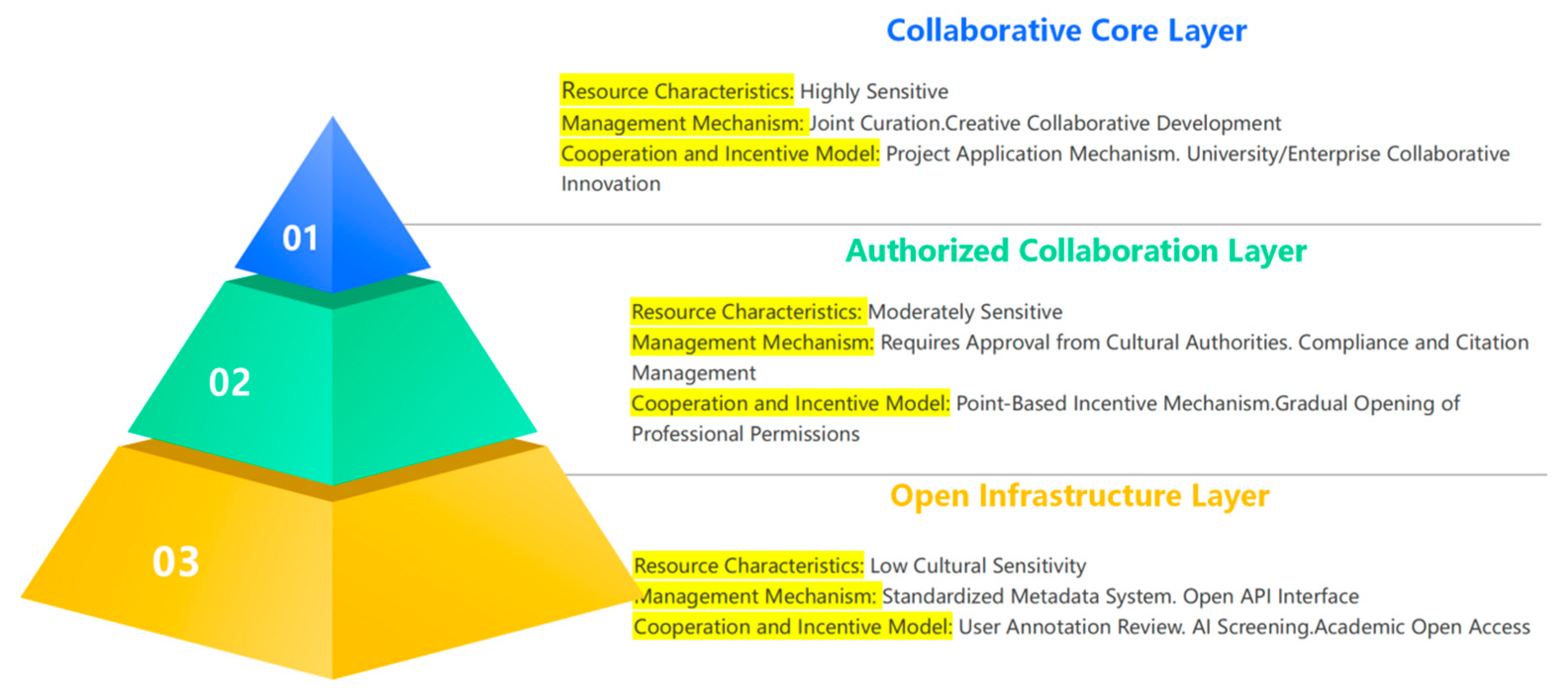

4.2. Hierarchical Sharing and Standardized Co-Construction Mechanism for Digital Image Resources

Against the backdrop of significant differences in the levels of digitalization and copyright policies between China and South Korea, the question of how to achieve the co-construction and sharing of resources has become a key issue for deepening cultural cooperation between the two nations. To address this, the establishment of a “three-tiered image resource sharing mechanism” that balances tiered management, risk control, and alignment with international standards is particularly crucial. This mechanism classifies resources into three levels based on their cultural sensitivity and copyright status (as shown in

Figure 4), each corresponding to varying degrees of openness and management requirements. Its goal is to achieve a dynamic balance between resource utilization and cultural preservation.

In the foundational open-access tier, the primary focus is on image resources with clear copyright ownership and low cultural sensitivity, such as traditional paintings and ceramics. This tier is systematically opened to academic research and non-commercial dissemination through a standardized metadata system and open API interfaces. To ensure the quality of resources and consistency of terminology, it is essential to establish a strict data verification mechanism that combines manual review with AI screening, thus ensuring the high-quality circulation of foundational data.

As the cultural sensitivity of the resources increases, the authorization and collaboration tier must strike a more delicate balance between protection and utilization. These resources include ceremonial images, traditional totems, and other cultural symbols, which require approval from cultural authorities before being shared. To incentivize proper use, it is suggested to introduce a point-based incentive system that encourages users to comply with citation norms and contribute knowledge, progressively unlocking higher levels of access and fostering cross-disciplinary and cross-field innovative research.

At the highest level, the collaborative core tier, the focus shifts to highly sensitive resources such as religious art and court symbols. Both China and Korea need to foster cultural reproduction and cross-cultural transmission of image resources through joint curating and creative collaboration, centered around contextual construction and symbolic interpretation. An open project application mechanism can be established to broadly invite university research teams, young artists, and cultural-tech enterprises to participate. This should be supported by professional guidance and talent development programs, thus forming a healthy ecosystem of multi-agent collaborative innovation.

To sustain the operation of this resource-sharing system, the establishment of a front-end risk monitoring and proactive early-warning mechanism is indispensable. By tracking key indicators such as the evolution of data formats, public opinion trends, and copyright disputes in real time, and analyzing these with AI algorithms, potential risks can be identified early and interventions can be implemented promptly. Additionally, it is recommended to set up a rapid evaluation committee composed of ethics and legal experts from both China and Korea to ensure that sensitive incidents can be initially assessed and responded to within 24 h, effectively reducing cultural conflicts and legal risks.

Moreover, the legal and cultural adaptation issues arising from cross-border cooperation must also be integrated into the governance framework. Introducing a cross-border risk assessment system that covers data sovereignty, semantic misinterpretation probabilities, and legal compliance, along with the establishment of a joint expert database and regular cooperation with international institutions such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), will contribute to enhancing the stability and compliance of resource flows.

In the design of the rights and responsibilities system, the roles and duties of each party should be clearly defined. Cultural authorities are responsible for certifying cultural values and determining ethical boundaries, while museums are tasked with image collection and the maintenance of metadata standards. Digital cultural copyright coordination bodies are responsible for overseeing resource classification and the operation of transaction mechanisms. Research institutions and content developers must strictly adhere to resource use agreements within the authorization framework and legalize the rights and responsibilities of all parties through multilateral agreements to reduce the potential for future disputes.

Regarding benefit distribution, this article proposes a cultural data trust mechanism based on NFT technology, allowing for the quantification of resource contributions and intelligent revenue sharing on the blockchain. The system can dynamically adjust the revenue distribution ratio based on AI analysis depth, cross-cultural semantic mapping, and user frequency, with a compensation mechanism for rare but highly culturally valuable resources, thus promoting fair resource flow and continuous innovation. Moreover, the benefit distribution algorithm should be regularly reviewed and optimized to ensure fairness and transparency over the long term.

Looking forward, to strengthen China and Korea’s voice in international cultural data governance, it is necessary to actively align with the WIPO digital copyright governance framework and maintain consistency with international standards such as the Berne Convention. Both countries could jointly release a multilingual “Image Use and Ethics White Paper”, develop open interfaces compliant with international standards like Europeana, and promote the construction of international digital cultural heritage image credit identifiers, thereby enhancing the credibility and recognition within global cultural networks.

Finally, to support the long-term operation of the mechanism and sustainable cultural development, it is recommended to establish a dedicated digital development fund for cultural heritage. The fund can generate income through annual resource transactions, which can be used to support the acquisition, restoration, and innovative reuse of endangered image resources, thus forming a virtuous cycle of risk-sharing, value-sharing, and cultural reciprocity. This would provide continued solid support for the global dissemination of China and Korea’s cultural heritage image resources.

4.3. User Participation-Driven Cultural Co-Creation and Dissemination Pathways

In cross-cultural digital image practices, the regional differences in user participation habits are a crucial factor to consider when designing user systems. Korean users tend to engage through gamified experiences, while Chinese users place greater emphasis on deepening understanding and creativity within the framework of knowledge structures. Based on this, a tiered, three-stage user participation system should be established to expand diverse participation pathways and promote cultural co-construction and knowledge exchange through experience activation, creative empowerment, and research deepening.

At the experience activation level, public-facing interactive programs, such as “Cultural Puzzle” apps, can be launched. These programs would include fun gameplay such as image fragment recognition, artifact pattern comparison, and virtual restoration challenges. To enhance the interactivity and sense of reward, points earned during participation could be exchanged for museum cultural products, immersive experience tickets, and customized guided tour services. By lowering the entry barrier, user interest can be stimulated, while simultaneously increasing user retention and a sense of belonging, laying a foundation for further engagement.

On the basis of the preliminary interest established through experiences, the creative empowerment mechanism offers more autonomous participation opportunities for advanced users. For instance, through the establishment of an “East Asian Visual Narrative Workshop”, users could independently curate themed digital exhibitions using modular exhibition structure templates (such as timeline, thematic association, or symbolic comparison) and a wealth of Chinese and Korean image resources. To ensure content quality, user-submitted exhibition works will be reviewed by an expert committee based on artistic quality, historical accuracy, and dissemination potential. Approved works will receive online display and promotional support, thereby encouraging the development of individual narratives and cross-cultural visual expressions.

Building on this, the research deepening mechanism, which is aimed at professional scholars, is designed to foster high-level academic collaboration and knowledge production. By constructing a high-precision image database covering categories such as Chinese and Korean ancient patterns, mythological images, and folk visuals, and supporting a structured tagging system and comparative analysis tools, it will provide support for cross-cultural visual research like the “Evolutionary Path of Dragon Symbolism.” Additionally, the green review channel established with collaborative Chinese and Korean journals reduces the barriers to publishing research outcomes, fostering international exchanges and knowledge sharing in bilateral iconology research.

Considering the new characteristics of Generation Z users in terms of cultural cognition and information reception, it is necessary to implement a “dual-track narrative” communication strategy that strengthens cultural identity and sustained participation willingness through both emotional guidance and knowledge construction. On the emotional track, the interactive drama series “Adventure in East Asian Civilization”, developed by the Korean side, guides users to participate in situational interpretation through symbol selection, generating personalized cultural fusion paths. On the knowledge track, the Chinese-led “Visual Knowledge Corridor”, which combines image data, narrative text, and AI explanations, creates an experience space that integrates learning, display, and interaction. Social features such as Q&A, discussion walls, and result display walls are set up within this space to encourage users to exchange insights and co-create content, further enhancing community vitality and user engagement.

To ensure the continuous optimization of the user participation system and dynamic balance of Sino-Korean cultural differences, a periodic feedback and evaluation mechanism should be established. Through surveys, behavioral data tracking, and open suggestion channels, user experience and changing needs can be timely understood, allowing for the dynamic adjustment of participation modes and content strategies. In cross-cultural communication, cultural sensitivity must be highly valued, with the implementation of multilingual annotation systems, sensitive content warning mechanisms, and expert review processes to avoid misunderstandings and stereotypes, and promote cognitive guidance and cultural understanding. With the collaborative operation of these mechanisms, Sino-Korean digital iconology cooperation is expected to achieve systematic updates and improvements in user satisfaction, laying a solid foundation for the digital preservation and dissemination of East Asian cultural heritage.

4.4. Construction of the East Asian Visual Symbol Dissemination Network and Cross-Cultural Adaptation

Based on the “same origin, different flow” nature of Sino-Korean cultures, this study proposes the establishment of a three-tiered symbol transformation system to facilitate the effective dissemination and cross-cultural adaptation of cultural symbols.

At the core symbol level, elements with highly localized characteristics, such as Chinese characters and Confucian ritual vessels, should adopt an “explanatory communication” strategy. For example, in the Forbidden City’s “Digital Artifacts Database”, each Chinese character image would be accompanied by bilingual etymological analyses in Chinese and Korean, detailing its semantic evolution and cultural changes in the historical contexts of both countries, helping users deepen their understanding of the profound cultural meanings.

At the common symbol level, shared cultural symbols between China and Korea, such as celadon and gardens, can be presented using a “comparative narrative” strategy. For instance, an interactive documentary titled “The Cross-Sea Journey of Qingbai Porcelain” could be developed, using the image evolution of Longquan Kiln and Goryeo celadon as the narrative thread, demonstrating the innovative paths and regional differences of cultural symbols in cross-cultural dissemination, thus enhancing users’ comparative thinking and cross-cultural understanding.

At the innovative symbol level, traditional cultural symbols will be reconstructed and created with contemporary aesthetic appeal. The fusion of Korea’s “Taekwondo” sportswear patterns and Chinese Hanfu elements could be developed into virtual fashion images with international expressive power and disseminated globally through TikTok and other social media platforms, creating “de-contextualized” communication that attracts young global users’ attention and secondary creation.

To ensure the effectiveness of symbol transformation, it is necessary to simultaneously establish an evaluation mechanism for the dissemination effects of symbols, regularly monitoring and analyzing various dimensions, including audience participation, cultural understanding, and social media diffusion. Based on this, content design and dissemination pathways can be continuously optimized, ensuring that the dissemination process respects cultural depth while conforming to cross-cultural reception principles.

In terms of dissemination channel layout, considering the cultural acceptance preferences of different regions, targeted localized communication strategies should be formulated. For the Southeast Asian market, leveraging the historical commonality of the Chinese character cultural sphere, a “Maritime Silk Road Digital Image Exhibition” could be launched, showcasing cultural exchange examples between China, Korea, and Southeast Asia. This could include portraits of Korean crew members in Zheng He’s fleet and fragments of Goryeo celadon excavated in Vietnam, with AR guidance and cooperation with local museums to enhance immersive experiences.

For the European and American markets, the “Cultural Decoding” concept could be promoted through a series of short videos titled “East Asian Image Codes”, using a suspense narrative approach to analyze Sino-Korean symbolic metaphors, such as comparing the differences in the symbolism of dragon motifs in imperial authority and folk beliefs. The content would cater to fragmented consumption habits and adapt to platforms like YouTube Shorts and Instagram Reels, boosting international dissemination.

For the Japanese and Korean domestic markets, it is necessary to create a “Cultural Memory Resonance” scenario. By setting up a “Daily Image Dialogue” column on Naver and Weibo, users could compare the landscape imagery in works like “A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains” and “The Dwelling in the Qingbai Mountain” to stimulate discussion and emotional resonance, further promoting cultural identification and exchange.

To enrich the content format and enhance audience engagement, diverse activities such as cultural-themed mini-games, interactive H5 pages, and online cultural challenges could be introduced, breaking the single-mode pattern of traditional image exhibitions or short video dissemination, increasing fun and immersion. At the same time, regular audience feedback mechanisms should be established across dissemination channels, using big data analysis to dynamically adjust content and strategies, ensuring a more precise response to the cultural needs and interests of different audience groups.

Furthermore, throughout the entire cross-cultural communication process, cultural sensitivity and adaptability issues must be given utmost attention. Prior to content planning and communication design, thorough research on cultural taboos and sensitive points should be conducted to avoid misinterpretation and conflict risks, ensuring that audiences from different regions can correctly understand and accept Sino-Korean cultural symbols, truly achieving harmonious deepening of cross-cultural communication.

4.5. Institutional Innovation and Risk Governance in Cross-Cultural Cooperation

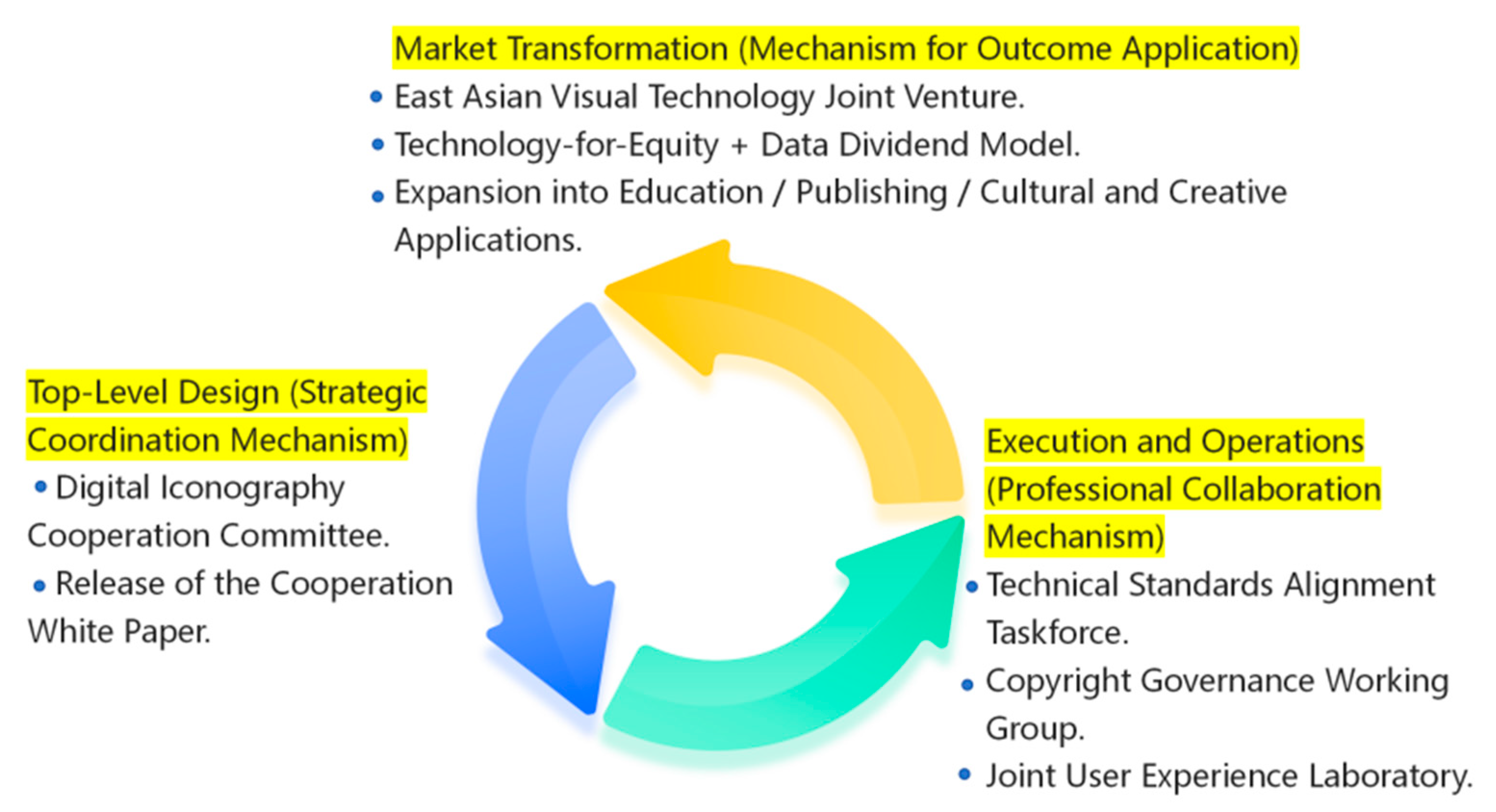

As Sino-Korean digital cultural heritage cooperation continues to deepen, issues such as policy differences, technical barriers, and mismatched market mechanisms have gradually emerged, becoming significant constraints to the collaborative development of both sides. In response to these challenges, this study proposes a three-tiered collaborative governance framework—comprising “top-level design, operational execution, and market transformation” (as shown in

Figure 5)—with the aim of providing institutional cooperation and sustainable development pathways to support Sino-Korean iconological practices.

At the top-level design level, it is recommended that the cultural departments of China and South Korea jointly take the lead in establishing a ministerial-level “Digital Iconology Cooperation Committee” as the highest institution for strategic decision-making and resource coordination. The committee can periodically publish a “Sino-Korean Digital Cultural Heritage Cooperation White Paper” to clarify the phased cooperation goals and key tasks, ensuring that both parties reach a high level of consensus on macro policies and laying the institutional foundation for subsequent specific operations.

In terms of operational execution, it is necessary to simultaneously establish three permanent collaborative institutions to form a specialized division of labor and an efficient execution system. First, the “Technical Standards Coordination Group” should focus on key technical compatibility issues, such as unified XR interfaces and quantum algorithm energy consumption control, to ensure seamless integration of joint projects at the infrastructure level. Secondly, the “Copyright Governance Working Group” could explore cross-border copyright confirmation and protection paths based on NFTs and smart contracts, breaking the limitations of traditional copyright governance in international cooperation. Thirdly, the “User Experience Joint Laboratory” should jointly develop user participation mechanisms from a cross-cultural perspective, enhancing the inclusiveness and interactivity of digital exhibitions and providing diverse, seamless experiences for both China and South Korea, as well as for a broader audience.

At the market operation level, this article proposes the establishment of a Sino-Korean joint venture, “East Asia Visual Technology”, which adopts an innovative cooperation model of “technical equity + data dividends” to promote the commercialization of cultural heritage digital assets. For example, an AI-based Sino-Korean image search tool could be jointly developed to expand application scenarios in education, cultural creation, publishing, etc., thereby achieving a virtuous cycle from technological development to market application. Through the progressive layout of this three-tiered framework, efficient interaction can be formed between policy coordination, mechanism implementation, and outcome transformation, strengthening the institutional foundation and practical support for Sino-Korean cultural cooperation.

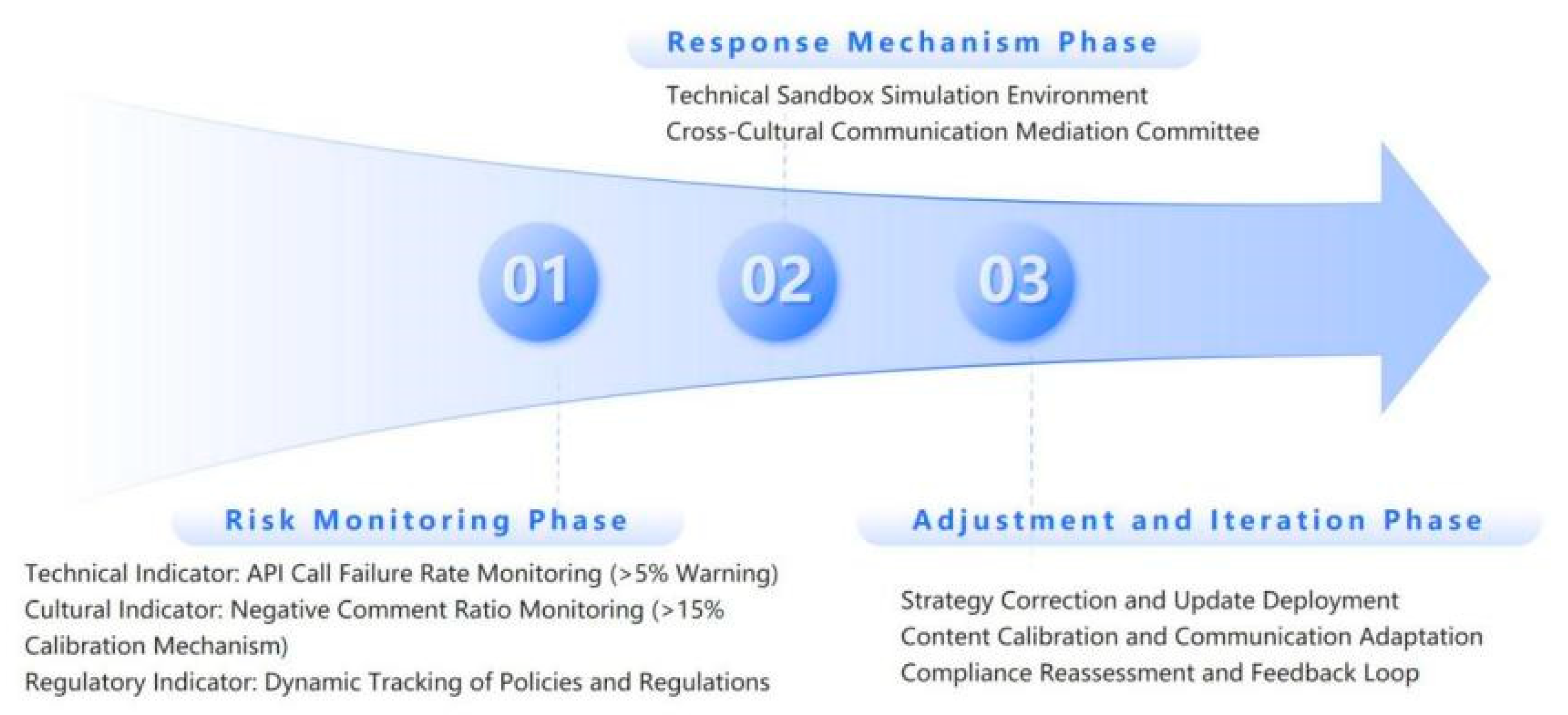

However, in cross-cultural cooperation practices, potential risks such as technical standard discrepancies, copyright disputes, and communication biases cannot be overlooked. Therefore, this article further proposes the construction of an integrated “Monitoring-Response-Iteration” risk governance system (as shown in

Figure 6) to ensure a dynamic balance between stability and innovation in the project.

In the risk monitoring phase, at the technical level, real-time monitoring of the joint platform’s API failure rate (with a warning triggered when the failure rate exceeds 5%) and quantum algorithm energy consumption indicators can be used to promptly detect potential technical risks. At the cultural level, a social media sentiment analysis model should be applied to monitor the proportion of negative comments, setting a “misreading index” threshold (e.g., initiating a content calibration mechanism when negative comments exceed 15%) to prevent cultural misinterpretation and emotional fluctuation risks. At the institutional level, it is necessary to dynamically track changes in relevant policies and regulations in both China and South Korea, assessing the impact of new regulations on the compliance and sustainability of collaborative projects. For example, potential adjustments may be required due to revisions of South Korea’s “Cultural Industry Promotion Act” or the implementation of China’s “Data Security Law.”