A Global Perspective on Ecotourism Marketing Trends: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the key themes in ecotourism marketing between 2003 and 2025?

- RQ2: What are the challenges and opportunities for ecotourism marketing?

- RQ3: What are the key research gaps and future research directions

2. Review of Literature

3. Research Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

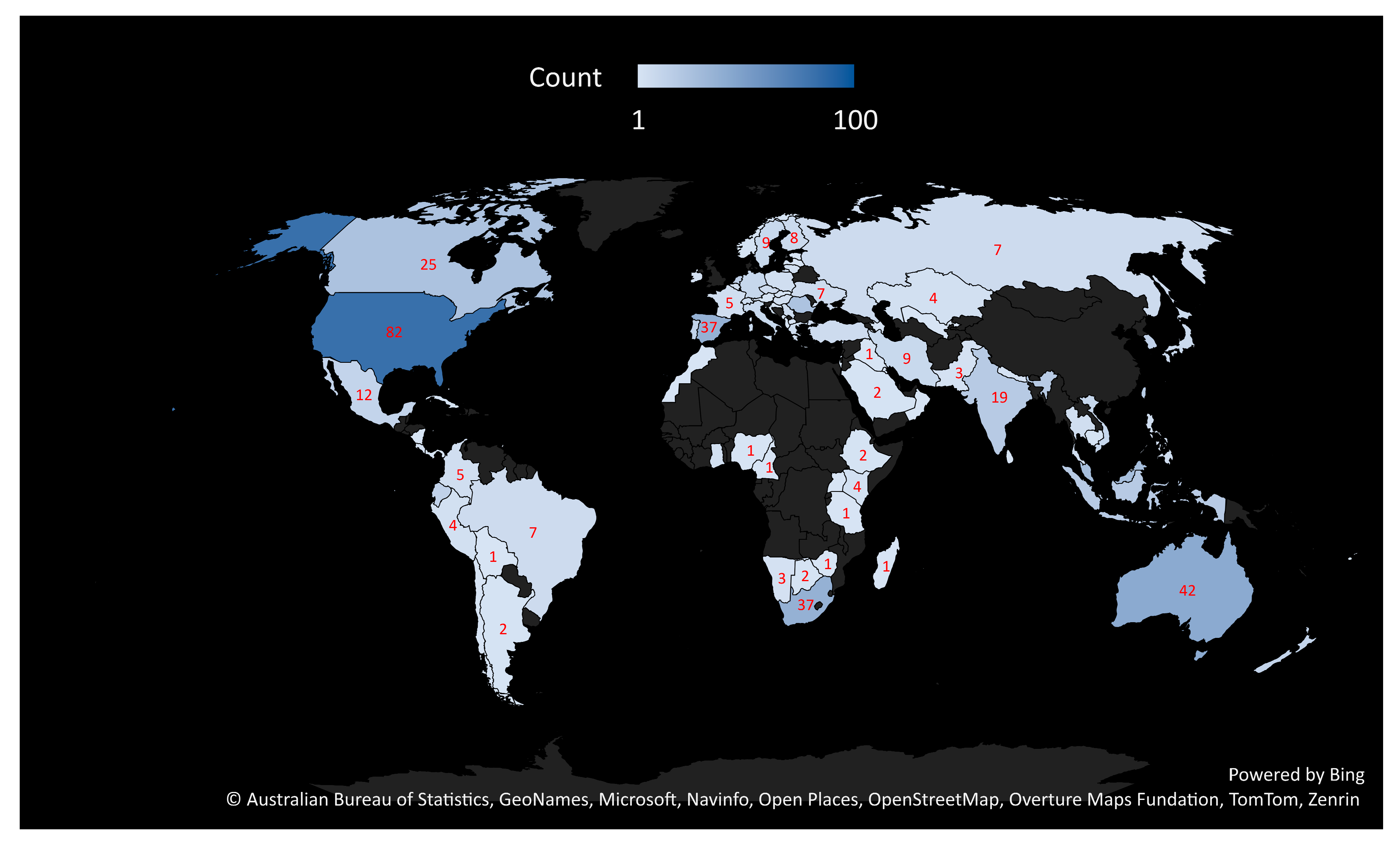

4.1. Annual Publications and Global Trends of Documents on Ecotourism Marketing

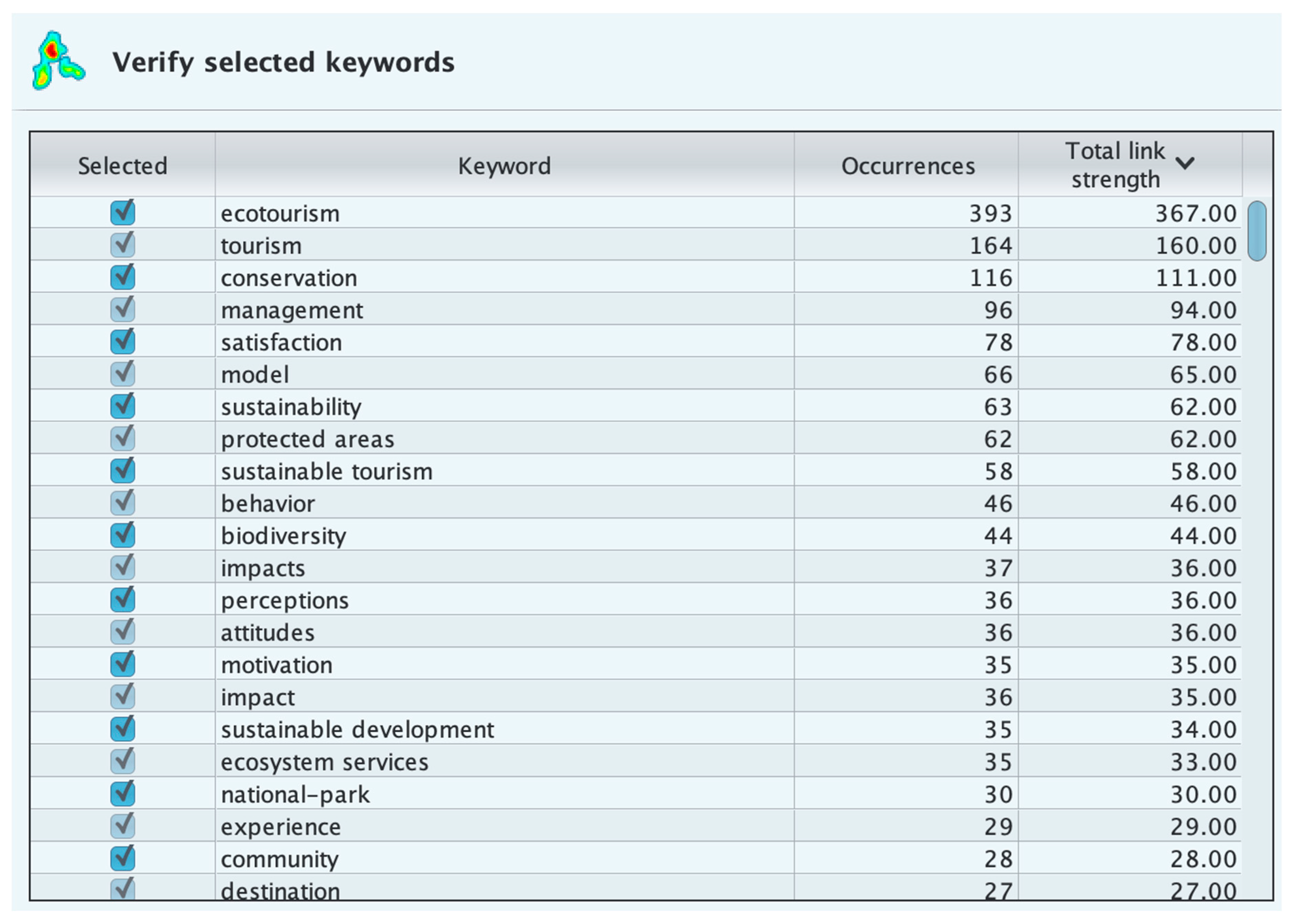

4.2. Key Thematic Areas in Ecotourism Marketing

4.2.1. Ecotourism Marketing for Conservation and Ecosystem Services

4.2.2. Ecotourism Marketing for Ecotourist Satisfaction and Loyalty

4.2.3. Technology and Ecotourism Marketing

4.2.4. Practical and Theoretical Implications of the Study

5. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadi Dehrashid, A.; Valizadeh, N.; Gholizadeh, M.H.; Ahmadi Dehrashid, H.; Nasrollahizadeh, B. Perspectives of Climate Change. In Climate Change; Bandh, S.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 369–388. ISBN 978-3-030-86289-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, K. A Comprehensive Review of Climatic Threats and Adaptation of Marine Biodiversity. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal-e-Hasan, S.M.; Mortimer, G.; Ahmadi, H.; Abid, M.; Farooque, O.; Amrollahi, A. How Tourists’ Negative and Positive Emotions Motivate Their Intentions to Reduce Food Waste. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2039–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K. Evolving Narratives in Tourism and Climate Change Research: Trends, Gaps, and Future Directions. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, V. Promoting Energy Strategies on Eco-Certified Accommodation Websites. J. Ecotourism 2010, 9, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvarishvili, N.; Devadze, A.; Turmanidze, N.; Gogelia, M.; Nakashidze, N.; Phalavandishvili, N.; Tsintsadze, L. The impact of ecotourism on the diversity and ecological condition of the ecosystems of the protected areas of Adjara. Reliab. Theory Appl. 2024, 19, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, N.; Meng, C.S.; Watabe, M.; Zainal, N.; Siew, J.K.K. Carbon Footprint of Tourism Activities Including Transportation, Accommodation, and Infrastructure: A Critical Analysis. In The Need for Sustainable Tourism in an Era of Global Climate Change: Pathway to a Greener Future; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhtiagung, G.N.; Radyanto, M.R. New Model for Development of Tourism Based on Sustainable Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 448, 012072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, M.E.; George, B. Global Warming and Tourism: Chronicles of Apocalypse? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2012, 4, 332–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavolová, H.; Bakalár, T.; Tokarčík, A.; Cimboláková, I. The Sustainable Management of Ecohotels for the Support of Ecotourism—A Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, P.B. Contextualising the Meaning of Ecotourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.; Setiawan, B.; Muhaimin, A.W.; Shinta, A. The Role of Coastal Biodiversity Conservation on Sustainability and Environmental Awareness in Mangrove Ecosystem of Southern Malang, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šenková, A.; Kormaníková, E.; Šambronská, K.; Matušíková, D. Perception of overtourism in selected European destinations in terms of visitor age and in the context of sustainable tourism. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2022, 45, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, T.; Sudatta, B.P.; Das, D.B.; Srichandan, S.; Baliarsingh, S.K.; Raulo, S.; Singh, S.; Samal, R.N.; Mishra, M.; Bhat, I. Irrawaddy Dolphin in Asia’s Largest Brackish Water Lagoon: A Perspective from SWOT and Sentiment Analysis for Sustainable Ecotourism. Environ. Dev. 2023, 46, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Bi, C. Marketing the Community-Based Eco-Tourism for Thai and Chinese under the New Media Era for Local Authorities. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 4481–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shasha, Z.T.; Geng, Y.; Sun, H.; Musakwa, W.; Sun, L. Past, Current, and Future Perspectives on Eco-Tourism: A Bibliometric Review between 2001 and 2018. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 23514–23528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochado, A.; Teiga, N.; Oliveira-Brochado, F. The Ecological Conscious Consumer Behaviour: Are the Activists Different? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyratne, S.N.; Arachchi, R.S.S.W. Ecotourism or Green Washing? A Study on the Link Between Green Practices and Behavioral Intention of Eco Tourists. In Future of Tourism in Asia; Sharma, A., Hassan, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 51–63. ISBN 978-981-16-1669-3. [Google Scholar]

- Antari, N.P.B.W.; Connell, D. Tukad Bindu in Bali, Indonesia: Ecotourism or Greenwashing? Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 1049–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, A.; Slotow, R.; Fraser, I.; Di Minin, E. Ecotourism Marketing Alternative to Charismatic Megafauna Can Also Support Biodiversity Conservation. Anim. Conserv. 2017, 20, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Hong, C.-F.; Lee, C.-H.; Chou, Y.-A. Integrating Multiple Perspectives into an Ecotourism Marketing Strategy in a Marine National Park. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 948–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannakis, G.E.; Vlachos, P.A.; Koritos, C.D.; Kassinis, G.I. Are Publicly Traded Tourism and Hospitality Providers Greenwashing? Tour. Manag. 2024, 103, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, A.; Sancha, P.; Gessa, A. Beyond Chartering: Adapting the Offer to Customer Behavior for a Sustainable Yachting Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, İ.; Gürlek, M. Green Influencer Marketing: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Validation: An Application to Tourism Products. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2181–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, C. Food Heritagization and Sustainable Rural Tourism Destination: The Case of China’s Yuanjia Village. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.H.; Shehata, H.S.; El-Dief, M.; Salem, A.E. The Social Responsibility of Tourism and Hotel Establishments and Their Role in Sustainable Tourism Development in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 33, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtapuri, O.; Giampiccoli, A. Tourism, Community-Based Tourism and Ecotourism: A Definitional Problematic. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2019, 101, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-Y. Sustainable Tourism Development Based upon Visitors’ Brand Trust: A Case of “100 Religious Attractions”. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Andrades-Caldito, L.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Is Sustainable Tourism an Obstacle to the Economic Performance of the Tourism Industry? Evidence from an International Empirical Study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P.C.; Dube, K. Bibliometric Analysis of Trends and Development in Religion and Green Tourism Behavior. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2445771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Shah Nordin, A.O.; Abdullah, S.; Marzuki, A. Geopark Ecotourism Product Development: A Study on Tourist Differences. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P.C.; Dube, K. Trends and Development in Green and Sustainability Marketing: A Bibliometrics Analysis Using VOSviewer. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Veríssimo, D.; MacMillan, D.C.; Godbole, A. Stakeholder Perceptions of Potential Flagship Species for the Sacred Groves of the North Western Ghats, India. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2012, 17, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.; Wittig, G.R. Bibliometrics; AllM Books: Watford, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lawani, S.M. Bibliometrics: Its Theoretical Foundations, Methods and Applications. Libri 1981, 31, 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, W.W.; Wilson, C.S. The Literature of Bibliometrics, Scientometrics, and Informetrics. Scientometrics 2001, 52, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Han, H.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Wider, W. Bibliometric Analysis on Green Hotels: Past, Present and Future Trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 8, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Toro, O.N.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Palacios-Moya, L.; Uribe-Bedoya, H.; Valencia, J.; Londoño, W.; Gallegos, A. Green Purchase Intention Factors: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2356392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRyalat, S.A.S.; Malkawi, L.W.; Momani, S.M. Comparing Bibliometric Analysis Using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Databases. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2019, 152, e58494. [Google Scholar]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. A Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of E-Learning Adoption Using VOSviewer. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2022, 23, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P.C.; Dube, K. Willingness to Pay in Tourism and Its Influence on Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabibibi, M.A.; Dube, K.; Thwala, K. Successes and Challenges in Sustainable Development Goals Localisation for Host Communities around Kruger National Park. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitumetse, S.O. The Eco-tourism of Cultural Heritage Management (ECT-CHM): Linking Heritage and ‘Environment’ in the Okavango Delta Regions of Botswana. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, X.; Lee, H.M.; Zhang, Y. The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Li, A. Environmental and Social Outcomes of Ecotourism in the Dry Rangelands of China. J. Ecotourism 2023, 22, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzengi, B.K.; Gandiwa, E.; Muboko, N.; Mutanga, C.N. Towards Sustainable Community Conservation in Tropical Savanna Ecosystems: A Management Framework for Ecotourism Ventures in a Changing Environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 3028–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Bi, C.; Wei, X.; Jiang, D.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Rasoulinezhad, E. Eco-Tourism, Climate Change, and Environmental Policies: Empirical Evidence from Developing Economies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzeni, M.; Kim, S.; Del Chiappa, G.; Wassler, P. Ecotourists’ Intentions, Worldviews, Environmental Values: Does Climate Change Matter? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, M.; Stephen, P.; Trupp, A. Determining Ecotourism Satisfaction Attributes—A Case Study of an Ecolodge in Fiji. J. Ecotourism 2020, 19, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, I.; Roy, G. How Eco-Service Quality Affects Tourist Engagement Behaviour in Ecotourism: Eco-Consciousness and Eco Activity-Based Learning and S-O-R Theory. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2025, 50, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmazyari, H.; Mirhadi, S.H.; Joppe, M.; Kalantari, K.; Decrop, A. Ecolodge Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets: A New Typology of Entrepreneurs; The Case of IRAN. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharte, M.; Lee, P.; Vick, S.; Bowler, M. Polling the Public to Select Flagship Species for Tourism and Conservation-A “Big Five” for the Peruvian Amazon? Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, K.; Quevedo, J.; Rifai, H.; Alifatri, L.; Ulumuddin, Y.; Sofue, Y.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Mangrove Forest Food Products as Alternative Livelihood Measures: Mangrove Conservation by Community in Muara Gembong, Bekasi Regency, Indonesia. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R. Incentivizing Endemic Biodiversity Conservation under a Warming Climate through Market-Based Instruments. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2024, 13, 322–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N. Decommodifying Nature through Commoning: An Alternative for Tourism and Private Protected Areas. Tour. Geogr. 2024, 22, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Meng, C.; Xiao, Y. Mechanisms and Influencing Factors of Cultural Ecosystem Services Value Realization. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qumsiyeh, M.B.; McHugh, C.; Shaheen, S.; Najajrah, M.H. Bio-Cultural Landscape and Eco-Friendly Agriculture in Al-Arqoub, South Jerusalem, Palestine. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 1489–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P. Ecotourism from a Conceptual Perspective, an Extended Definition of a Unique Tourism Form. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Hung, P.; Dung, T.; Dinh, N.; Kien, N.; Tri, T.; Quy, L.; Phan, N.; Dung, V. Exploring Relationships Between Nature-Based Destination Attractiveness, Satisfaction, Perceived COVID-19 Risk, and Revisit Intention in Bach Ma National Park, Vietnam. Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, U.; Nemaorani, T.; Naudé-Potgieter, R.; de Klerk, C. Key Determinants of Visitor Satisfaction and Post-Visit Intentions at a Museum in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. J. PARK Recreat. Adm. 2025, 43, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, S.; Carvalho, J.M.S. Unlocking the Dichotomy of Place Identity/Place Image and Its Impact on Place Satisfaction for Ecotourism Destinations. J. Ecotourism 2024, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Seo, M.; Byun, J. The Experience of Video Interpretation and Satisfaction. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2024, 22, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Viquez-Paniagua, A.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Pérez-Orozco, A.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, W. Implications of Destination Marketing from the Perspective of the Perceived Value of Foreign Tourists. COGENT Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2392258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ao, C.; Liu, B.; Cai, Z. Exploring the Influence of Multidimensional Tourist Satisfaction on Preferences for Wetland Ecotourism: A Case Study in Zhalong National Nature Reserve, China. Wetlands 2021, 41, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Borja-Morán, J. Motivations as a predictor of satisfaction and loyalty in ecotourism. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliarni, N.; Hurriyati, R.; Disman, D.; Hendrayati, H.; Warlina, L. Marketing strategy of ecotourism in Uzbekistan and Indonesia. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. 2023, 10, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, R.; Xiang, C.; Zhao, D.; Li, Y. Influence of Eco-Agricultural Tourism Relationship Marketing on Customer Loyalty Based on Product Brand Trust. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2019, 20, S41–S48. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Kim, K. Experiential Value and Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention in Rock-Climbing Tourism: The Role of Place Attachment and Biospheric Value. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 48, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Arora, N. Do Instagram Reels Influence Travelers’ Behavioral and e-WOM Intentions for the Selection of Ecotourism Destination? J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 2603–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Amin, H.; Seperi, Y. Faith, Ecology and Leisure: Understanding Young Muslim Tourists’ Attitudes towards Mangrove Ecotourism. J. Islam. Mark. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.; Rahmad, V.; Hamid, S.; Anandya, A.; Purwanti, P.; Sofiati, D.; Wardani, M.; Supriyadi, S. Digital Marketing Strategy Development for Recovery Ecotourism Visit After COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparison Study on BJBR and Kampung Blekok Mangrove Ecotourism, Indonesia. AGRIS-LINE Pap. Econ. Inform. 2024, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasciuc, I.-S.; Constantin, C.P.; Candrea, A.N.; Ispas, A. Digital Landscapes: Analyzing the Impact of Facebook Communication on User Engagement with Romanian Ecotourism Destinations. Land 2024, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Pickering, C. Destination Image of Chitwan National Park, Nepal: Insights from a Content Analysis of Online Photographs. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour.-Res. Plan. Manag. 2022, 37, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbicanová, G.; Mocko, M.; Kaisová, D. Use of the geocaching for the tourism development in Horny Liptov Region. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Brno, Czech Republic, 12–16 June 2019; pp. 539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, K.F.; Koh, L.Y.; Tan, L.Y.H.; Wang, X. The Determinants of Virtual Reality Adoption for Marine Conservation. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, W. Evolution of Spatial Pattern and Configurational Path of Ecotourism Comfort in Chengdu City. Sustainability 2025, 17, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Wen, C. Sustainable Tea Garden Ecotourism Based on the Multifunctionality of Organic Agriculture Based on Artificial Intelligence Technology. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 8696490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dube, K.; Ezeh, P.C. A Global Perspective on Ecotourism Marketing Trends: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136035

Dube K, Ezeh PC. A Global Perspective on Ecotourism Marketing Trends: A Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136035

Chicago/Turabian StyleDube, Kaitano, and Precious Chikezie Ezeh. 2025. "A Global Perspective on Ecotourism Marketing Trends: A Review" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136035

APA StyleDube, K., & Ezeh, P. C. (2025). A Global Perspective on Ecotourism Marketing Trends: A Review. Sustainability, 17(13), 6035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136035