1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Over the past decade, the tourism marketing field has been subject to an unprecedented transformation as a result primarily of the unprecedented growth in social media platforms. What started as an added form of communication is now an integral part of tourism branding that affects tourists’ decision-making and enables personal interaction [

1]. Social media platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and TripAdvisor have not just transformed the promotion of tourism products and destinations, but also reformed tourists’ attitudes and perceptions about traveling [

2,

3].

This transformation signifies much more than a mere evolution of technology; it hints at a cultural change. The level of “Instagrammability” of a destination [

4] now matches its historical significance or ecological value [

5]. The flows of tourists are increasingly influenced by algorithmic trends, viral social media posts, and influencer-generated content rather than historical significance, heritage, value for money, or sustainability. Aesthetics, trending posts, and visibility often overshadow quality and depth of authentic experience [

6].

From a critical point of view, this paradigm raises issues in relation to power, representation, and control. Whose voices dominate the social media space? Who benefits from the visibility generated by viral campaigns? Research shows that tourism content often reinforces narrow cultural ideals and privileges urban, Western-centric aesthetics [

7,

8]. Local communities are frequently left out of these conversations, even as their environments are commodified for digital spectacle.

From a marketing standpoint, the landscape has evolved faster than the academic theory can explain. Metrics such as likes, shares, and engagement rates are volatile and platform-dependent, and often poorly correlated with long-term behavior or loyalty [

9]. Meanwhile, practitioners scramble to adapt to shifting algorithms and audience behaviors, often without a clear framework for measuring ethical or strategic impact [

10]. Empirical studies provide valuable insights into these complexities. For instance, Soares, Mendes-Filho, and Gretzel demonstrated that hotel managers often adopt new technologies primarily to mimic competitors and gain legitimacy—especially on platforms such as TripAdvisor—highlighting how technology adoption is driven more by external institutional pressures rather than by internal strategic innovation [

11]. Similarly, Somera and Petrova highlight that hotels pursuing digital innovations face substantial challenges related to capability gaps and leadership limitations, complicating the multi-stage process from initial detection of innovation needs through institutionalization [

12]. Furthermore, Alsharif, Isa, and Alqudah, in their comprehensive review, illustrate that the adoption of smart tourism systems, including IoT and ICT solutions, remains uneven [

13]. Companies often demonstrate initial enthusiasm in pilot stages but subsequently encounter significant hurdles related to technological readiness, ethical considerations, and data governance frameworks during broader implementation [

11,

12,

13]. Collectively, these studies offer detailed sector-specific context, revealing that companies’ responses to digital change are fragmented and varied. Some embrace smart technologies strategically to enhance competitiveness and visibility, while others lag behind due to organizational, infrastructural, or ethical barriers. Our study builds upon this nuanced context by going beyond descriptive or adoption-focused analyses, critically examining structural logics of digital platforms—such as algorithmic visibility, governance biases, and shifting promotional authority—to uncover systemic forces shaping tourism businesses’ engagement with digital transformation.

Recent empirical studies offer valuable insights into the nuanced responses by tourism companies to digital transformation, illustrating both positive engagement and significant barriers. Sousa, Alén, Losada, and Melo highlight several operational and managerial challenges tourism managers face when integrating virtual reality (VR) technologies, including high initial investment costs, limited technological skills within teams, and resistance to change among staff and customers [

14]. Despite recognizing VR’s potential for enhancing visitor experiences and competitive differentiation, managers often struggle with practical implementation hurdles and adapting business models accordingly. Further research by Sousa et al. reveals how the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated interest and adoption of VR among tourism businesses, but also clarified ongoing structural and cultural limitations, including gaps in digital competencies, infrastructural inadequacies, and lingering skepticism toward digital innovations among traditional market segments [

15]. Thus, while some tourism businesses actively embrace digital tools as strategic assets for branding, customer engagement, and immersive experiences, widespread adoption remains fragmented, cautious, and context-dependent.

All previous cases underscore the complex, uneven landscape of digital transformation in tourism operations and branding strategies, supporting the assertion that companies indeed struggle significantly in adapting effectively and strategically to new digital environments. By critically examining such cases, our study broadens the understanding of prior descriptive research, contributing a deeper theoretical analysis of the underlying structural logics—such as algorithm-driven content curation, platform governance, and the implications of digital authority—shaping this evolving digital landscape.

Despite a growing body of literature, much of the existing research remains descriptive—focused on trends or campaign performance—while failing to interrogate the structural logic of social media itself [

16,

17]. For example, influential reviews, such as by Leung et al. [

1] and Gretzel [

2], document consumer and supplier uses of social platforms such as TripAdvisor and Facebook but maintain a descriptive orientation without engaging with algorithmic filtering, platform governance, or the systemic forces at play. Similarly, Ge and Gretzel take an important step toward analyzing the rhetorical–visual structures of tourism marketing on such platforms as Weibo, revealing how message formats shape destination image—but this remains one of the few examples addressing post hoc structural features rather than theorizing how these structures emerge from platform logic [

18]. Comprehensive conceptual treatments, such as the critical review by Gössling [

19], underline the need for deeper engagement with technological affordances, data biases, and the power dynamics embedded in social media platforms. There is a need to move beyond surface metrics and influencer ROI to explore deeper, systemic transformations: the collapse of promotional authority, the aesthetics of digital travel culture, AI-immersive experiences, and the long-term implications of platform governance for tourism development.

This paper starts from that premise: that social media is not just a set of tools—it is a force reshaping the tourism sector at multiple levels—economic, cultural, ethical, and psychological.

1.2. Purpose of the Study

This paper aims to critically review the state-of-the-art research on social media in tourism marketing. Specifically, it seeks to (1) identify major trends and theoretical developments in the field between 2015 and 2025; (2) conduct a meta-analysis to quantify the impact of social media marketing on tourism-related outcomes; (3) expose gaps and biases in the existing research; and (4) propose a multidisciplinary research agenda that pushes the boundaries of conventional marketing paradigms.

1.3. Relevance and Contribution

While the volume of research in this area has grown rapidly, the literature remains fragmented. Much of it is descriptive, platform-specific, or focused narrowly on short-term campaign metrics. This paper attempts to address the call for a synthesized, critical review that brings clarity to the field and guides future inquiry.

It contributes to the current body of knowledge by offering: (1) a consolidated view of what is currently understood and what remains unclear about social media’s role in tourism marketing; (2) a meta-analytic assessment of empirical findings across diverse studies; (3) conceptual clarity through engagement with interdisciplinary theories and models; and (4) a call for more inclusive, ethical, and technologically informed research approaches.

1.4. Structure of the Paper

This paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 outlines the methodological approach, including criteria for study selection and the meta-analytic techniques used.

Section 3 reviews the evolution of social media in tourism marketing.

Section 4 dives into key themes such as influencer marketing, user-generated content, and AI-driven personalization.

Section 5 summarizes dominant theoretical frameworks.

Section 6 presents the results of the meta-analysis.

Section 7 and

Section 9 identify interdisciplinary connections and critical research gaps.

Section 10 proposes a future research agenda, and

Section 11 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

This study employed a two-pronged research design anchored in established research methodologies. First, we conducted a systematic critical literature review of peer-reviewed academic publications on social media in tourism marketing between 2015 and 2025. This approach followed the key principles from Kitchenham’s guidelines for systematic reviews [

20], the PRISMA statement [

21], and the best practices in the tourism domain [

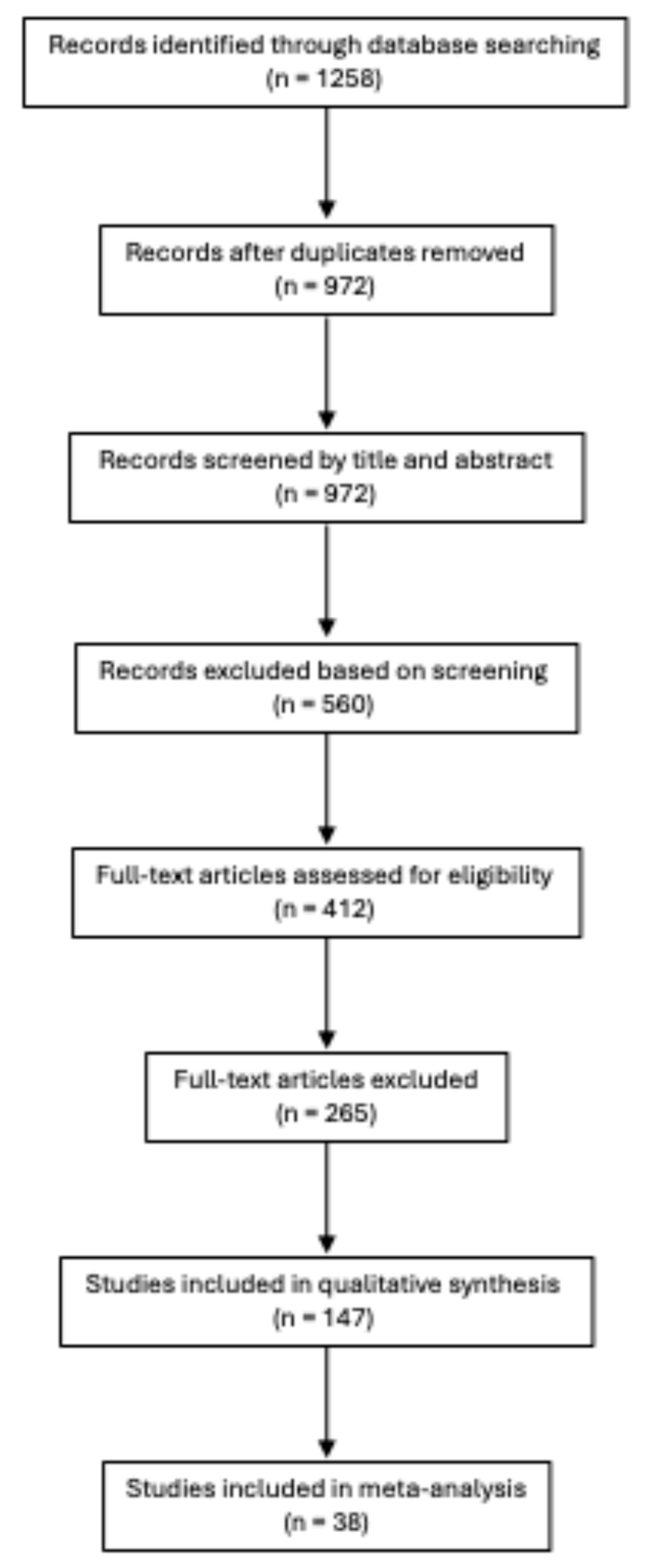

22], ensuring transparent and replicable identification, screening, inclusion, and appraisal of relevant studies. Initially, a total of 1258 articles were retrieved from the Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases using comprehensive Boolean search strings. Duplicate removal was performed using EndNote software, resulting in 972 unique studies. Screening by title and abstract reduced the number to 412 articles, which underwent a rigorous full-text evaluation for methodological soundness and applicability based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 147 articles met the inclusion criteria for qualitative analysis. A PRISMA flowchart documenting each selection stage is included to ensure transparency and replicability (see

Figure 1).

Second, we performed a meta-analysis of empirical studies that quantified the effects of social media on specific tourism marketing outcomes—specifically, destination image, travel intention, and user engagement. Our meta-analytic design was informed by seminal methodological work in tourism and hospitality meta-analyses [

23,

24], which outline rigorous procedures for effect size estimation, heterogeneity assessment using Cochran’s Q and I

2 statistics, and publication bias evaluation. Studies selected for the meta-analysis (

N = 38) clearly reported effect sizes or provided sufficient data for their calculation and demonstrated methodological rigor in their design, sampling, and statistical analysis.

Together, these complementary stages enabled us to achieve two key objectives: to synthesize and integrate theoretical contributions across the literature and to empirically assess the current state of evidence regarding social media’s impact on tourism marketing. By aligning our methodology with accepted frameworks—including PRISMA-based systematic review and robust meta-analytic protocols—we ensured both the rigor and relevance of our conclusions, while situating our research design within the broader scholarly discourse.

2.1. Systematic Critical Analysis

The current review adheres to the principles outlined by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), as articulated by Liberati et al. [

21], adapted to incorporate a critical approach that explicitly examines not only substantive findings but also epistemological and methodological biases prevalent within the literature. The meta-analysis specifically employed rigorous methodological procedures informed by seminal meta-analytic frameworks described by Borenstein et al. [

25], which emphasize standardized effect size calculations, heterogeneity assessment, and bias evaluation techniques. Additionally, we drew on the established meta-analytic practices from the tourism literature, exemplified by Afshardoost and Eshaghi’s robust examination of relationships between tourism-related constructs [

23], thereby ensuring both theoretical and methodological alignment with recognized standards in quantitative synthesis research.

2.1.1. Data Sources

The Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases were searched for studies published between January 2015 and February 2025 using the following Boolean search strings: (“social media” OR “digital platform” OR “Instagram” OR “TikTok” OR “YouTube” OR “Facebook”) AND (“tourism marketing” OR “destination branding” OR “travel promotion” OR “online engagement”).

2.1.2. Criteria for Inclusion

Journal articles that were anonymously peer-reviewed (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods); substantial focus on social media in tourism marketing; and publications in the English language.

2.1.3. Criteria for Exclusion

Conference papers, theses, unpublished documents, and non-peer-reviewed or predatory journals; and publications where social media was not the main focus of the study.

A total of 412 articles were thoroughly evaluated based on their applicability and methodological soundness, and 147 were selected for qualitative analysis. Thematic coding was utilized for each study, and particular attention was paid to influential variables including the platform being studied, geographic location, intended results, theoretical context, and types of marketing efforts used.

The critical analysis aspect questioned deeper patterns: Which voices dominate the literature? What theoretical assumptions persist? Which parts of the world are underrepresented? What ethical, cultural, or power dynamics are overlooked?

2.2. Meta-Analysis

Among the 147 studies, 38 specific empirical articles met statistical requirements for inclusion in a meta-analysis. These papers were selected on the basis of three major conditions: (1) the study described effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, r, odds ratios) or provided sufficient data to estimate them; (2) the variable(s) used was(were) clearly linked to a tourism marketing system of measurement, influenced by social media; and (3) research design, sampling procedures, and statistical analysis reflected high methodological rigor.

2.2.1. Primary Outcomes Evaluated

Destination image: how social media content influences and/or shapes perceptions of destinations.

Travel intention: likelihood of visiting a destination after exposure to social media content.

User engagement: social media interactions (likes, comments, shares) and their relationship to behavioral consequences such as reservations or brand loyalty.

2.2.2. Meta-Analytic Approach

A random-effects model was used to account for the variability between the studies.

Heterogeneity was evaluated by using Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics.

Moderator constructs explored how variables such as platform type, geographical region, and user demographics had an impact on effect sizes.

The role of meta-analysis went beyond mere aggregation of the results; it aimed at clarifying patterns of causation and identifying inconsistencies and unjustified generalities contained in the empirical literature.

2.3. Thematic Analysis and Critical Integration

The remaining 109 studies were qualitatively analyzed using an inductive thematic analysis approach inspired explicitly by Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory methodology [

26,

27]. NVivo qualitative analysis software supported systematic coding procedures. Following Charmaz’s recommendations, the coding process involved iterative stages: (1) initial open coding, where key concepts and insights were identified through line-by-line analysis; (2) focused coding, in which the initial codes were organized and refined to identify recurring patterns; and (3) theoretical coding, which integrated focused codes into coherent themes reflecting broader conceptual insights [

27]. Coding was conducted independently by two coders, achieving intercoder reliability through regular discussions, with discrepancies resolved by consensus, following the procedures recommended by Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña [

28]. Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was calculated and achieved a value of 0.82, indicating substantial intercoder agreement and methodological rigor as recommended by Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña [

28]. Significant categories included:

Influencer marketing dynamics.

Strategies for user-generated content (UGC).

Message personalization and algorithmic targeting of the audience.

Specific platform affordances.

Crisis management (e.g., COVID-19).

Throughout this process, constant comparison methods were used to ensure that identified themes were grounded robustly in empirical data [

29], allowing concepts to emerge organically rather than relying on predetermined categories. To further enhance conceptual coherence, thematic findings were systematically cross-referenced with the outcomes of the meta-analysis. This methodological triangulation, suggested by Denzin [

30], allowed for integrating robust empirical evidence (“what works”) with a critical exploration of overlooked or underexplored areas within the literature (“what’s overlooked”).

2.4. Limitations

This methodology is not without limitations. The inclusion of only English-language peer-reviewed studies may introduce cultural and linguistic bias. The rapid evolution of such platforms as TikTok and Threads means recent phenomena may be underrepresented. Finally, publication bias and inconsistent reporting standards in primary studies may affect the meta-analysis.

Despite these constraints, this combined methodological approach offers a robust, interdisciplinary, and critically engaged overview of the state of research on social media in tourism marketing.

3. Evolution of Social Media in Tourism Marketing

Over the past fifteen years, social media has not simply added a new layer to tourism marketing—it has remade it. The once-linear flow of messaging from destination marketers to tourists has collapsed into a dynamic feedback loop where influence, identity, and place branding are co-produced by brands, platforms, and users. What began as a communication tool has evolved into a fully integrated marketing ecosystem, and its evolution can be traced across five overlapping but distinct phases.

3.1. Phase 1: User-Generated Content and the Social Web (2008–2014)

The beginning of social media use in tourist promotion came at the same time as the Web 2.0 technology became available. Groundbreaking platforms such as TripAdvisor, Flickr, and Facebook facilitated a shift from institutionally generated content to member-generated content [

31,

32]. This new development meant that tourist accounts, which had previously been dictated by destination management organizations (DMOs), were increasingly being created by common tourists [

31,

33].

The user-generated content (UGC) quickly became a new trust currency [

1]. Research conducted during this time showed its potential for building perceived authenticity and for shaping decision-making processes [

3,

34]. However, such content’s authenticity was unregulated and nonstandardized, leading to early concerns around misinformation, rating manipulations, and undermining brand identity [

35,

36].

DMOs initially struggled to engage. Their responses were often reactive or confined to corporate pages with low interactivity [

37]. However, some innovative agencies began adopting community management models, shifting from broadcasting to facilitating conversation [

38,

39]. This phase set the stage for deeper engagement—but the platforms were still maturing.

3.2. Phase 2: Emergence of the Visual Economy and Influencer Culture (2014–2019)

By the mid-2010s, the marketing terrain shifted again. Visual-first platforms—Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat—became central to tourism storytelling. Destinations were not just described anymore; they were stylized, filtered, and framed into bite-sized, aspirational content [

32].

Instagram, in particular, changed the game. Its architecture rewarded aesthetics, repetition, and emotional tone—qualities that aligned perfectly with tourism’s visual grammar [

5,

40]. The “Instagrammability” of a destination began to influence not just where people traveled, but how they experienced those places on the ground [

4]. Restaurants painted “selfie walls”, viewpoints became photo queues, and landmarks were often visited for their photogenic value alone [

3,

41].

Simultaneously, the rise of travel influencers marked the emergence of a new kind of marketing agent: one that blurred the line between individual traveler, content producer, and brand ambassador. Unlike celebrities, influencers built micro-audiences based on perceived authenticity and relatability [

42,

43]. Brands began reallocating budgets from traditional advertising spending to influencer partnerships, hoping to piggyback on trust and audience reach [

44,

45].

This era intensified the commodification of place. Destinations became digital symbols to be consumed and shared. While this boosted visibility, it also exacerbated overtourism in fragile locations and deepened inequality between digitally visible and invisible destinations [

46,

47]. In many cases, the experiences being sold were stylized approximations, carefully curated to fit the feed rather than reflect cultural or geographic complexity [

10].

3.3. Phase 3: The Algorithmic Revolution and Hyper-Personalization (2020–2022)

The next phase of evolution was defined less by content and more by how content was distributed. Platforms became increasingly algorithm-driven. Discovery was no longer user-led; it was engineered by machine learning models that fed users what they were statistically most likely to engage with [

48,

49]. Algorithms optimized for time-on-platform and engagement began shaping not just what users saw, but how they imagined and accessed travel information.

For tourism marketers, this created both opportunities and risks. On the one hand, paid promotions and organic reach could be hyper-targeted based on demographics, behaviors, or even real-time location data [

50]. On the other hand, visibility became unstable—dependent on opaque engagement metrics, algorithmic volatility, and platform-specific ranking systems. Campaign performance could fluctuate dramatically with minor changes to algorithm logic, making strategic planning more reactive and uncertain [

51].

Artificial intelligence also began shaping the user journey in more proactive and personalized ways. Chatbots handled routine queries across booking platforms and DMO websites. Dynamic content feeds adjusted in real time based on scrolling patterns or device usage. Increasingly, travel agencies and platforms integrated AI-powered recommender systems to deliver tailored itineraries, targeted offers, and predictive booking suggestions [

52,

53]. These tools promised convenience, efficiency, and conversion—but at a cost.

While these developments improved personalization, they also raised deeper ethical and experiential concerns. Critics warned of algorithmically reinforced “filter bubbles” that reduced exposure to diverse destinations, cultures, or lesser-known experiences [

54,

55]. As user journeys became more predictive and optimized, the serendipity and exploration often associated with travel risked being minimized. Furthermore, the extensive use of personal data for behavioral targeting reignited longstanding debates around digital privacy, especially in jurisdictions with weaker regulatory oversight [

56].

Few studies during this time examined the long-term implications of such hyper-personalization. Most research focused on short-term behavioral metrics—click-through rates, likes, shares, and booking intent—while leaving critical questions of consumer agency, destination diversity, and algorithmic accountability underexplored. As AI continues to mediate visibility and access in tourism, the need for deeper, longitudinal, and critical research becomes increasingly urgent.

3.4. Phase 4: Platform Fragmentation, Authenticity, and Community Trust (2022–2025)

The most recent phase in social media’s evolution has been defined by platform fragmentation and a growing skepticism toward polished digital marketing. TikTok emerged as the dominant discovery engine for younger travelers, overtaking Google for trip inspiration in Gen Z cohorts [

16,

57]. The platform’s short-form, candid, and often chaotic content upended traditional tourism storytelling. Instead of scripted hotel walkthroughs or drone footage, users responded to raw honesty—“travel fails”, DIY tips, and unfiltered local interactions [

58,

59,

60].

At the same time, Reddit, Discord, and niche Facebook groups surged in importance as communities of trust, providing alternatives to the algorithmically manicured mainstream. Travelers increasingly sought out peer advice and authentic reviews in closed, interest-based spaces rather than public influencer feeds [

47,

61].

This unveiled a paradox that challenges marketing practitioners. The polished visual content that once drove engagement now risks being seen as inauthentic. Influencers have begun rebranding themselves as “content creators” or “storytellers”, signaling a pivot toward narrative depth and transparency [

44,

62]. Platforms, too, have adapted: Instagram introduced Notes and Channels to mimic community forums, while YouTube doubled down on Shorts to compete with TikTok [

63].

Amid all this, tourism marketing has become more precarious and democratized. Campaign virality is unpredictable. User-led narratives can uplift or damage a brand in only a few hours, blurring the line between brand asset and user meme, which has become thinner than ever. Perhaps most critically, the architecture of influence is no longer controlled by marketers—it is distributed, unstable, and mediated by opaque algorithms [

10,

47].

3.5. Phase 5: Integration of AI, Big Data, and Predictive Analytics (2025–?)

While social media platforms have long been recognized as powerful tools for engagement and promotion in tourism, their capabilities have expanded dramatically through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics. This shift represents not just a technological upgrade, but a fundamental reconfiguration of how tourism marketing is conceived, executed, and measured.

The convergence of AI and big data enables marketers to move beyond general audience segmentation into the realm of hyper-personalization. Artificial intelligence applications use considerable amounts of user-related data, including geolocation, scrolling history, clicks, and affective responses, in order to provide content that is contextually relevant at a moment in time [

52]. Specifically, within the confines of the realm of tourism, this functionality allows for personalized tourist itineraries for Bali, based on what users did previously while traveling, what they can afford, and how they responded to similar destinations.

The use of predictive analytics has been applied extensively for forecasting tourist demand and creating advertising strategies. Airlines and tourism board organizations use machine learning algorithms for forecasting spikes in consumer demand, which are driven by seasonality, social media interactions, and major global news events. For instance, Marriott has integrated chatbots fueled by artificial intelligence for finalizing real-time bookings for clients, while Expedia has embedded AI into recommendation platforms for boosting conversion rates [

37].

Another equally valuable aspect is social media analysis using natural language processing (NLP). Processing large datasets that include reviews, captions, and hashtags allows tourism professionals to identify changes in tourist sentiments, spot emerging hotspots, and rectify service lapses in a timely manner. Sentiment analysis and topic modeling have been widely applied as some of the NLP techniques being adopted to measure reputation across such networks as TripAdvisor, Reddit, and Twitter [

64,

65].

However, such advances come along with ethical concerns and structural weaknesses. The increased lack of transparency in algorithmic decision-making—particularly around recommendation criteria, ranking, and targeting—raises questions about equity, representation, and power relationships [

10]. Biased data can lead algorithms to reinforce exclusionary discourse, prioritizing Western forms of tourism, trendy city destinations, and beautiful content, often at the cost of less commercialized and more diverse alternatives.

Privacy concerns have also escalated. The tourism industry’s reliance on third-party data brokers and platform APIs places user data in the hands of actors with uneven transparency and accountability. Travelers may unknowingly surrender vast amounts of behavioral data—location, interactions, preferences—which are monetized with little oversight or opt-out ability.

Moreover, automation in content delivery has reduced opportunities for spontaneous discovery. Personalized feeds, though efficient, tend to reinforce user preferences rather than expand them, potentially narrowing the scope of travel inspiration. This creates “digital filter bubbles” where users are repeatedly shown similar content, limiting serendipity and reducing the visibility of emerging or underrepresented destinations [

66].

Despite these risks, the integration of AI and big data is unlikely to slow down. The competitive advantage they offer is too significant for brands and DMOs to ignore. The challenge, then, is not whether to adopt these tools, but how to deploy them responsibly, with transparency, inclusivity, and sustainability as guiding principles.

Critically, the academic literature on this topic has struggled to keep pace. Most existing studies either celebrate AI’s efficiency or critique its risks in abstract terms. There is a notable lack of empirical research on how AI-powered tourism marketing affects consumer autonomy, destination diversity, and long-term brand loyalty. This gap presents a significant opportunity for future interdisciplinary inquiry that combines data science with tourism ethics and behavioral psychology.

3.6. Synthesis and Implications: Furthering Tourism Promotion Through Social Media

The evolution of social media in tourism marketing illustrates important changes driven by technological advances and demographic shifts. Long defined as top-down, one-way communication from organizations toward a passive audience, social media has become participatory and networked. The centralized powers of tourism have been replaced by a decentered network between influencers, travelers, and algorithmic platforms. This shift is not just about embedding new technology into established practice but is instead a radical remaking of goals: from dispersal of carefully curated images toward production of dynamic, real-time content and from simple communication with customers toward collaborative creation that involves growing numbers of people who are increasingly acting as creators of content; from mental imagery to travel inspiration [

67], including instigating emotions (e.g., pleasure and arousal) [

68].

These changes have important implications. The role of tourism marketing has shifted from essential corporate image maintenance to a concern for intentional management of that image in an increasingly dynamic environment controlled by such factors as emotional connections, consumer conduct, and organizational habits. The levels of transparency are guided not merely through innovative methodology but through algorithms that are not explicitly stated. Meanwhile, trust is increasingly developed not through official certification but through authenticity, shared social values, and past experience.

To successfully navigate this complex environment, scholars and marketers alike need to develop new literacies. Strategic agility is certainly required, but alone, it will not suffice. A deeper understanding of the operationally embedded logics in online tourist media—social, psychological, and ethical—is needed. This requires an analysis of critical issues such as representation, consent, privacy, and algorithmic bias. Many practices in the industry are reactive or trend-led, and scholarship often lags behind technological developments. What is needed, then, is an ongoing, interdisciplinary methodology that sees social media not as an external factor molding the touristic experience, nor as a marketing technology, but as an architectural building block for the touristic experience itself.

4. Key Themes Identified: Critical Review and Meta-Analysis

The meta-analytical exploration and overall evaluation highlighted well five major themes that characterize social media and tourism marketing relationships: (1) influencer marketing, (2) user-generated content (UGC), (3) artificial intelligence and personalization, (4) crisis communications and reputation, and (5) platform-specific strategies. Not only do these themes serve as recommendations for future research, but they have a direct impact on interactions between destinations, organizations, and tourists in cyberspace as well.

4.1. Influencer Marketing

The influencer phenomenon has moved swiftly into focus in academic discussion and evaluation in the field of tourism media research. The development of “travel influencers”, which refers to influential content creators who have high follower counts and earn revenues from monetizing audience interactions through collaborative content partnerships, has reshaped promotional strategies adopted by destinations. Influencers are increasingly found at the center of tourist promotions, acting as important go-betweens connecting enterprises and customers [

39,

55,

69].

These influencers combine advertising content with personal anecdotes, a practice that is seen as being more trustworthy and engaging than traditional advertising practices [

32,

36]. Their effect is based upon parasocial intimacy principles; they present a sense of familiarity, which then reinforces trust and persuasiveness [

69]. Audiences perceive influencers as authentic peers, not professional spokespeople, allowing branded content to feel native within a feed, rather than intrusive.

However, studies reveal growing concerns around authenticity erosion, undisclosed sponsorships, and brand dilution [

44]. Research shows that audience trust is highly conditional—when users detect overt commercial intent or repetitive brand promotion, engagement and credibility suffer [

43,

70]. Recent investigations also highlight how influencer marketing reinforces aspirational norms, class biases, and exclusionary aesthetics [

37], often under the guise of “authenticity”.

The influencer economy remains lightly regulated, with inconsistent transparency requirements across platforms and countries [

71]. Despite increasing calls for standardized disclosure practices, enforcement is limited and patchy, leaving ethical responsibility largely to individual creators and brands.

From a research standpoint, influencer marketing remains a fragmented and under-theorized domain. Much of the literature centers on influencer selection, engagement metrics, or short-term return on investment. Few studies interrogate the deeper power dynamics at play—who gets funded, whose experiences are amplified, and how cultural representation is constructed and commodified in digital tourism [

72].

Finally, emerging work has begun to explore influencer labor conditions, noting the precarious, always-on nature of content production, algorithmic dependency, and emotional burnout [

62,

73]. These insights point to a growing need for a critical and intersectional lens—one that not only analyzes influence as a marketing tool, but also as a sociotechnical phenomenon shaped by platform capitalism, inequality, and visibility politics.

4.2. User-Generated Content (UGC)

UGC, particularly in the form of photos, videos, and reviews, has transformed the tourism marketing playbook. Travelers trust other travelers more than official campaigns—a shift that reflects broader patterns of peer-to-peer trust and participatory culture [

3,

6,

74]. Platforms such as TripAdvisor, YouTube, and Instagram serve as decision-making ecosystems where content flows horizontally rather than top–down, enabling a more democratized yet decentralized production of destination narratives [

75].

Why it matters: UGC assists in destination image creation, expectation management, emotional engagement, and destination image [

5]. There is evidence that UGC not only influences travel intention but also post-holiday satisfaction, through the reconciliation between expectation and experience [

40,

59,

76]. UGC is both social proof and experiential foretaste—offering visual and narrative content that allows tourists to mentally simulate future experiences [

77].

However, UGC is subjective. It has an effect that is contingent upon content quality, user trustworthiness, and platform visibility. The prevalence of highly dramatized content has the potential to skew portrayals toward idealized or “Instagrammable” looks, excluding less exciting or more diverse experiences [

59]. Moreover, high volumes of positive content can create overhyped destinations, leading to visitor disappointment, carrying capacity strain, and eventual destination fatigue. Conversely, negative UGC—even if isolated—can disproportionately damage brand equity due to algorithmic amplification or emotional salience [

65].

UGC also raises ownership and consent issues. Tourist-generated media is often reappropriated by brands without compensation, consent, or credit. While legal frameworks are often vague, the ethical implications are clearer: marketers are profiting from unpaid digital labor, often sourced from users unaware of the commercial value of their contributions [

61]. These concerns are magnified when UGC features local communities, children, or culturally sensitive locations—raising questions about representational justice and digital colonialism [

15], considering the value co-created in the tourism ecosystem [

78].

Finally, most research treats UGC as a variable, not a phenomenon. There is limited engagement with the aesthetics, rhythms, or cultural codes of UGC production. Few scholars interrogate how UGC reinforces specific visual tropes—such as tropical beaches, rooftop pools, or street food—as globalized, aspirational icons. Through repetition and stylization, UGC can contribute to the commodification of place, turning lived destinations into visual products optimized for engagement, rather than cultural understanding or sustainability [

79].

4.3. Personalization and AI

The growing use of AI and big data has shifted tourism marketing from broadcasting to behavioral orchestration. Algorithms now personalize user experiences—from trip planning apps to targeted Instagram ads—based on preferences, browsing patterns, and prior behavior [

52,

65,

80]. These systems draw on vast datapoints—clickstreams, sentiment, dwell time, location—to dynamically tailor content that aligns with the user’s psychological profile and real-time context [

81].

Why it matters: Personalization increases relevance, boosts conversion, and enhances user satisfaction. AI systems can recommend flights, hotels, or destinations tailored to specific emotional states, mobility constraints, or budget thresholds. In theory, this leads to a smoother, more fulfilling customer journey and higher retention rates [

82,

83]. AI-enhanced personalization has also proven valuable in crisis contexts, such as COVID-19, helping adapt offers to changing travel restrictions and health concerns [

64].

Yet personalization also introduces ethical concerns [

84]. Filter bubbles, confirmation bias, and algorithmic exclusion can narrow the range of choices users see—limiting discovery and reinforcing digital inequality [

85]. Popular destinations receive disproportionate exposure, while emerging or alternative options are suppressed by platform logic. Personalization, in this sense, can become a mechanism of homogenization rather than empowerment.

Privacy is another issue: consumers often have little awareness of how much data are collected, how they are profiled, or how they are monetized by third-party systems [

86,

87]. Consent is frequently buried in unread terms, and data sharing across ecosystems (e.g., Facebook–Instagram–Booking.com) makes meaningful opt-out nearly impossible.

Moreover, personalization can create emotional manipulation risks. Recent research highlights how AI can exploit psychological vulnerabilities—e.g., through urgency cues, social proof, or mood-based pricing—to drive behavior that may not align with the user’s best interests [

88]. These subtle manipulations blur the line between assistance and coercion.

Academic work on AI in tourism marketing remains heavily techno-optimistic. Much of the literature focuses on functionality—recommendation accuracy, conversion rates, or user satisfaction—while overlooking systemic bias, algorithmic opacity, or consumer resistance. As AI takes on a more autonomous and affective role in shaping tourist behavior, there is a critical need for ethically grounded research that considers not just what AI can do, but what it should do—and under what constraints [

89,

90].

4.4. Crisis Communication and Reputation Management

Crisis response has emerged as a strategic priority in tourism marketing, particularly in the wake of global disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Social media platforms were central to how destinations communicated closures, safety protocols, and reopening plans [

47,

91]. They also became battlegrounds for public relations, misinformation, and community management. In the early weeks of COVID-19, for instance, destinations used platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and WeChat not only to inform but also to project reassurance, solidarity, and control [

92].

Why it matters: Effective social media use during crises can preserve brand trust, stabilize visitation intent, and support stakeholder coordination. Empirical research has proven that quick communication, sensitive messaging, and positive engagement are associated with crisis recovery and audience loyalty enhancement [

93,

94]. Those brands that modified their messaging in accordance with current discourse—health, well-being, and emotional relationships instead of promotion-related content—usually showed positive results in terms of enduring trust and crisis recovery.

However, many brands failed to adapt. Some communicated too late, others relied on tone-deaf messaging that ignored local suffering or public health guidelines [

95]. The pandemic exposed a gap in platform fluency—brands accustomed to curated, promotional content often struggled to pivot to crisis dialogue, especially in dynamic, emotionally volatile settings [

96]. Missteps—such as insensitive influencer campaigns or ambiguous updates—sometimes did more reputational harm than silence.

Furthermore, social media crises are often multi-actor environments, involving not just DMOs and brands, but travelers, residents, journalists, and platform moderators. This complicates message control and increases reputational volatility. User-generated backlash, viral misinformation, and algorithmic amplification can all escalate situations rapidly.

Despite its growing importance, crisis communication on social media remains undertheorized in tourism. There is a lack of integrated models that account for the real-time, interactive, and emotionally charged nature of social platforms [

97]. Much of the existing literature is descriptive or post hoc, focused on content analysis rather than strategy development. Adaptive frameworks—combining crisis typologies with platform logic and user dynamics—are still rare, despite increasing demand from practitioners.

Looking forward, more attention must be given to pre-crisis planning, cross-platform coordination, and response agility, especially as new crises emerge—from climate-induced disasters to geopolitical shocks and viral brand controversies.

4.5. Platform-Specific Strategies

One of the most underappreciated insights in the literature is that social media is not monolithic. Each platform has unique affordances, user cultures, and algorithmic logics that shape how content is created, shared, and consumed [

51,

98]. These affordances are not static; rather, they evolve in response to user behavior, platform updates, and broader sociotechnical trends.

Instagram emphasizes aesthetics, consistency, and visual branding. TikTok privileges spontaneity, humor, and virality. YouTube rewards long-form depth and storytelling. Twitter thrives on real-time commentary and controversy. Reddit fosters community expertise and authenticity. Each of these logics supports different modes of tourism representation, from the polished to the participatory. These differences are not trivial—they fundamentally affect how tourism narratives are constructed and received [

47,

65].

Why it matters: Platform literacy—understanding the native “language” of each space—is essential for marketing effectiveness. Yet, much of the academic literature treats platforms as interchangeable or generalizes insights from one (usually Instagram) to the entire ecosystem [

5,

99]. This flattening overlooks the fact that the same campaign may perform very differently across platforms, depending on such factors as algorithmic promotion, content format, or user demographics [

50].

Some recent studies push back against this. Guerreiro et al. show that TikTok’s informal, low-production-value aesthetic fosters a different type of trust than Instagram’s polished visuals [

59]. Meanwhile, Qu et al. reveal how YouTube comments provide valuable sentiment cues for destination marketers [

100], often revealing deeper emotional responses than Instagram likes or shares. Others have explored how Reddit’s community-driven norms provide rich qualitative feedback but resist overt marketing attempts, requiring more subtle, value-adding participation [

37].

Still, scholarly work remains platform-agnostic. There is a need for comparative, platform-specific analyses that account for changing algorithms, user base shifts, and affordance evolution. Recent work by Buhalis et al. emphasizes that “nowness”, co-creation, and real-time value delivery differ not just by segment but by platform logic [

101]. Tourism marketers must design content and campaigns not for “social media” in general, but for each platform’s architecture of visibility and engagement.

Additionally, new platforms continue to emerge. Threads, BeReal, and Discord each offer distinct marketing challenges and opportunities. BeReal’s anti-filter ethos contrasts sharply with Instagram’s aesthetic bias; Threads’ conversational style may revive aspects of early Twitter discourse; and Discord offers intimate, community-based tourism engagement that may be ideal for niche branding or loyalty programs [

39,

102].

Without platform-specific fluency, marketers risk tone-deaf messaging, low engagement, or reputational damage. Future research must better map the cultural grammar and technical affordance of each platform, especially as the social media landscape continues to fragment and evolve.

4.6. Synthesis and Implications: Five Themes Define the Terrain

The five core themes identified in this review—influencer marketing, user-generated content (UGC), personalization and artificial intelligence (AI), crisis communication, and platform-specific strategies—together form the intellectual backbone of contemporary research on social media in tourism marketing. Each of these themes analyzes distinct areas of digital mediation, promotion, and tourist consumption patterns. Taken together, these themes describe an increasingly dynamic, rapidly changing, and inherently interdisciplinary field that includes perspectives from marketing, media studies, technology, psychology, and cultural theory.

Despite the wide variety of topics involved in these challenges, there exists a common and pervasive lack of methodological and conceptual rigor in the literature. Within even discrete areas of inquiry, each study often stands alone, with little interdisciplinary cross-fertilization or inclusion into broader theoretical frameworks. This isolation results in redundancy, measurement inconsistency, and foreclosed comparative analysis opportunities. Much of today’s work is mainly based on measures of short-term participation, trends tied to individual platforms, or standalone case studies instead of examining systemic or long-term processes.

It is important to note the significant lack of longitudinal frameworks that track social media use throughout time and its correlation with offline conduct. Additionally, there is a lack of focus given to intersectional issues—most specifically in terms of how gender, race, class, or cultural identity shape online discussion and, vice versa, how these various identities get constructed through such interactions [

103]. Minimal research efforts try to connect online engagements and quantifiable results in the real world.

These gaps suggest that while the field has expanded in scope, it now faces a deeper challenge: to grow in depth, reflexivity, and relevance, aligning scholarly inquiry with the complex realities of digital tourism.

5. Identification of the Major Theoretical Frameworks Employed

The study of social media in tourism marketing has rapidly expanded, but its theoretical development remains uneven. Much of the existing literature is driven by managerial outcomes—engagement, conversion, loyalty—rather than foundational inquiry into the psychological, social, or cultural mechanisms at work. Nevertheless, several key theoretical frameworks have shaped the field’s evolution, while others remain underutilized or only recently emerging.

This section highlights the most influential theoretical approaches identified in the review and meta-analysis, including technology acceptance models (TAM/UTAUT); stimulus–organism–response (S–O–R); uses and gratifications theory (UGT); social exchange theory (SET); narrative and identity-based approaches (emerging).

5.1. Technology Acceptance and Behavioral Intention Models

The technology acceptance model (TAM) and its extensions, including UTAUT (unified theory of acceptance and use of technology), have been widely used to examine how tourists adopt digital platforms for information search, planning, or booking [

104,

105]. Studies applying the TAM typically focus on perceived usefulness, ease of use, and behavioral intention to use social media for travel purposes [

106].

These models have proven useful in explaining first-time use or platform adoption. However, their application in tourism contexts often lacks nuance—flattening complex social behaviors into linear, rational processes. Critics argue that TAM-based studies often ignore affective, symbolic, and cultural factors influencing social media engagement [

9,

107].

5.2. Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) Models

The S–O–R model is a popular framework for understanding how marketing stimuli—images, captions, videos—trigger emotional responses (organism) influencing behavioral outcomes such as travel intention (response) [

108]. It is particularly relevant in explaining how emotionally rich social media content impacts users’ perceptions of destinations.

S–O–R has been used to model the emotional impact of influencer posts, destination imagery, and interactive features such as polls or comment threads [

95]. However, the model’s effectiveness depends heavily on how “organism” variables—such as involvement, enjoyment, or trust—are conceptualized. The literature shows inconsistency in operationalization and a tendency to retrofit variables to fit the model rather than let theory drive design.

5.3. Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT)

The UGT provides a media-centric perspective, focusing on why individuals actively seek out certain platforms or content types. Applied to tourism, the UGT explains why travelers use social media for trip inspiration, information validation, social interaction, or self-presentation [

1,

109,

110].

This framework has been especially useful in explaining content creation behaviors, such as posting reviews, tagging locations, or engaging with influencer content. However, it often assumes rational and individualistic motives, underplaying the influence of algorithmic cues, social pressures, and monetization structures that increasingly shape user behavior on commercial platforms.

5.4. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

The social exchange theory posits that human relationships are guided by perceived rewards and losses related to such encounters. In the tourism marketing context, the SET comes into play when analyzing how value is created cooperatively between users and influencers or brands [

111,

112].

For instance, travelers may follow an influencer or brand account if they perceive informational or social value, while marketers benefit from exposure or the UGC. The SET has also been applied to understand online reviews and destination loyalty [

113].

However, the SET’s transactional logic may oversimplify complex relational dynamics. In the context of influencer marketing, for example, follower loyalty is not purely economic or rational—it is also emotional, aspirational, and shaped by identity alignment.

5.5. Emerging Approaches: Narrative, Identity, and Cultural Theory

Hitherto, a limited but growing body of research draws from the narrative theory, the identity theory, and cultural studies to explore how travelers use social media to construct and perform identity through travel narratives [

42,

114]. These approaches treat tourism not just as consumption, but as meaning-making.

Influencer content, tourist narratives, and online outings are explored as performative demonstrations through which people experience notions of authenticity, social capital, and belonging [

115,

116]. This focus then allows for a detailed exploration of representation, colonial aesthetics, and platform labor—areas that have been underexplored in traditional scholarship on tourist marketing.

While productive, these frameworks remain marginal in tourism scholarship and are further embedded in areas such as communication, media, or gender studies. Such frameworks applied to tourism marketing hold potential for constructing more evolved and context-based understanding of how online environments shape tourist experiences.

5.6. Synthesis and Implications: Dominant Theoretical Approaches

Theoretical development in social media tourism marketing research continues to lag behind the field’s rapidly shifting practical landscape. While frameworks such as the technology acceptance model (TAM), stimulus–organism–response (S–O–R), and the uses and gratifications theory (UGT) remain dominant, their appeal lies largely in their simplicity and quantifiability. These models are well-suited for predicting user adoption or engagement, but they fall short in capturing the social, cultural, and ethical complexities that now define the digital tourism experience.

What is missing is a broader theoretical lens—one that can grapple with questions of identity, representation, platform politics, and digital labor. The fast-evolving nature of social media, where trends shift overnight and platform logics are algorithmically governed, demands more than behavioral prediction. It requires theoretical approaches that are as agile and multidimensional as the media environments they aim to explain.

Moving forward, the task is not merely to apply familiar models to new contexts, but to rethink what theory is needed for a world where tourism is co-created through images, data, and social interactions. This means integrating critical perspectives, media theory, and cultural analysis with empirical inquiry—bridging the gap between what is happening and why it matters in the platform-shaped future of tourism marketing.

6. Meta-Analysis Findings

This section reports the results of a meta-analysis synthesizing the empirical evidence on the impact of social media marketing on three core tourism outcomes: destination image, travel intention, and user engagement. A total of 38 peer-reviewed studies published between 2015 and early 2025 met the inclusion criteria, each providing statistically analyzable data on the relationship between social media activity and consumer tourism behaviors.

6.1. Selection and Coding of Studies

The eligible studies presented the following characteristics: (1) reported quantitative metrics (Cohen’s d, Pearson’s r, or other effect sizes); (2) focused on the influence of social media content or strategy in tourism marketing contexts; (3) examined at least one of the following: perceived destination image, consumer intention to travel, or digital user engagement; and (4) used empirical methods with sample sizes ≥ 100 and transparent methodological procedures [

60,

117].

Each study’s design, location, platform focus, and theoretical framework were coded for moderator analysis. Effect sizes extracted were converted to Cohen’s d for consistency.

6.2. Meta-Analytic Procedure

The meta-analysis employed a random-effects model to accommodate heterogeneity across study contexts and measurement tools [

118]. The key steps included calculating weighted mean effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals, assessing heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q and I

2 statistics, and conducting moderator analysis based on region, platform, and methodology.

6.3. Summary of Effect Sizes

The meta-analysis aggregated data from 53 independent effect sizes across three primary outcome variables to evaluate the overall impact of social media marketing in tourism.

Table 1 presents these findings.

The above results put forward considerable evidence suggesting that social media use has a significant impact on significant behavioral trends among tourists within the sector. Of the three areas under study, the impact is strongest in terms of the destination image perception (d = 0.61), thus verifying that social media sites, especially those that are visual-based, such as Instagram and YouTube, influence people’s perceptions, judgments, and sentiments about vacation spots [

6,

35].

An effect size of 0.61 for Cohen’s d shows that consumer perceptions are substantially affected by social media-presented images of destinations. This result is significant in light of the fact that destination image is an exclusive factor in an overall scenario for consumer choice, which generally precedes and is an antecedent to behavioral intention [

25]. This result further acknowledges that perception building is of prime importance in the context of online channel-based promotion in the field of tourism.

The study shows that the intent factor, which was determined to be the second most affected (d = 0.54), falls into a level that is moderate in nature. This provides evidence for the proposition that social media content consumption affects destination awareness and, at the same time, increases the prospect of planning, booking, or setting destinations for future journeys. This aligns with earlier studies showing that user-generated content and influencer narratives act as trust-enhancing mechanisms that increase travelers’ willingness to act [

43].

The small-to-moderate effect on user engagement (d = 0.43) reflects the more complex and variable nature of online interactions. Engagement—likes, shares, comments—is highly dependent on content format, platform algorithms, and user mood, making it harder to standardize or consistently influence. However, the fact that social media still demonstrates a statistically significant effect suggests that strategic content design can reliably boost interaction, even amid high variability [

43].

The I

2 values, all exceeding 60%, indicate considerable heterogeneity, underscoring that these effects are not uniform across contexts. This justifies the need for moderator analyses (see

Section 6.4) and points to the importance of cultural, technological, and methodological context in interpreting effect sizes.

In this vein, the analysis unveils that social media marketing in tourism is not just influential—it is meaningfully transformative across perception, intention, and interaction. The field must now move toward nuanced, context-aware strategies that account for variability while leveraging the consistent power of social media to shape tourist behavior.

6.4. Moderator and Heterogeneity Analysis

Substantial heterogeneity was observed across all outcomes, suggesting contextual variability across studies, as measured by high I2 statistics (>60%) and significant Q-statistics (p < 0.05), indicating that variation in effect sizes was not solely attributable to sampling error. This suggests that contextual and methodological factors influence outcomes. Moderator analysis was therefore conducted across three dimensions: platform type, geographic region, and methodological design.

6.4.1. Platform Type

Studies examining Instagram and YouTube reported a notably stronger average effect on destination image (Cohen’s d = 0.68) than those focused on Facebook or Twitter (d = 0.44). This supports the previous literature suggesting that visual-centric platforms are more effective at evoking emotional responses and shaping perceptions due to their immersive and aesthetic content formats [

8]. Platforms optimized for visual storytelling appear to amplify persuasive power in the tourism context, especially when user-generated visuals and influencer narratives are combined.

6.4.2. Region

Research conducted in Western contexts (e.g., Europe, North America, Oceania) reported significantly higher effects on travel intention (d = 0.61) than studies from Asia, Latin America, or Africa (d = 0.38). These differences may reflect broader disparities in digital infrastructure, social media penetration, and platform-specific adoption trends [

91]. Additionally, Western markets often feature more mature content ecosystems and consumer familiarity with influencer culture, which may enhance the persuasive capacity of social media campaigns.

6.4.3. Methodology

Empirical research yielded effect sizes of higher magnitude (d = 0.63) than those found from survey-based cross-sectional designs (d = 0.49). This result highlights ongoing concerns about the limitations when using behavioral intention as a proxy for behavior. Controlled experimental designs can offer a clearer evaluation of causality and psychological impact [

119] under different conditions, such as different message frames, channels, or levels of interactivity.

These findings underscore the importance of context when interpreting the impact of social media marketing in tourism. Not all platforms are equally effective, not all audiences respond similarly, and not all research designs capture influence with the same fidelity. Future studies should account for these moderators when designing interventions or interpreting marketing outcomes. The results are presented in

Table 2.

The above table illustrates how the type of platform, geographic context, and research design significantly moderate the observed effects of social media marketing on tourism-related outcomes.

6.5. Publication Bias

To assess the potential for publication bias in the meta-analytic results, three complementary diagnostic techniques were employed: funnel plot visual inspection, Egger’s regression test, and the trim-and-fill method. These are standard approaches recommended for evaluating the robustness of effect size estimates and detecting the overrepresentation of statistically significant results in published literature [

120].

6.5.1. Funnel Plot Analysis

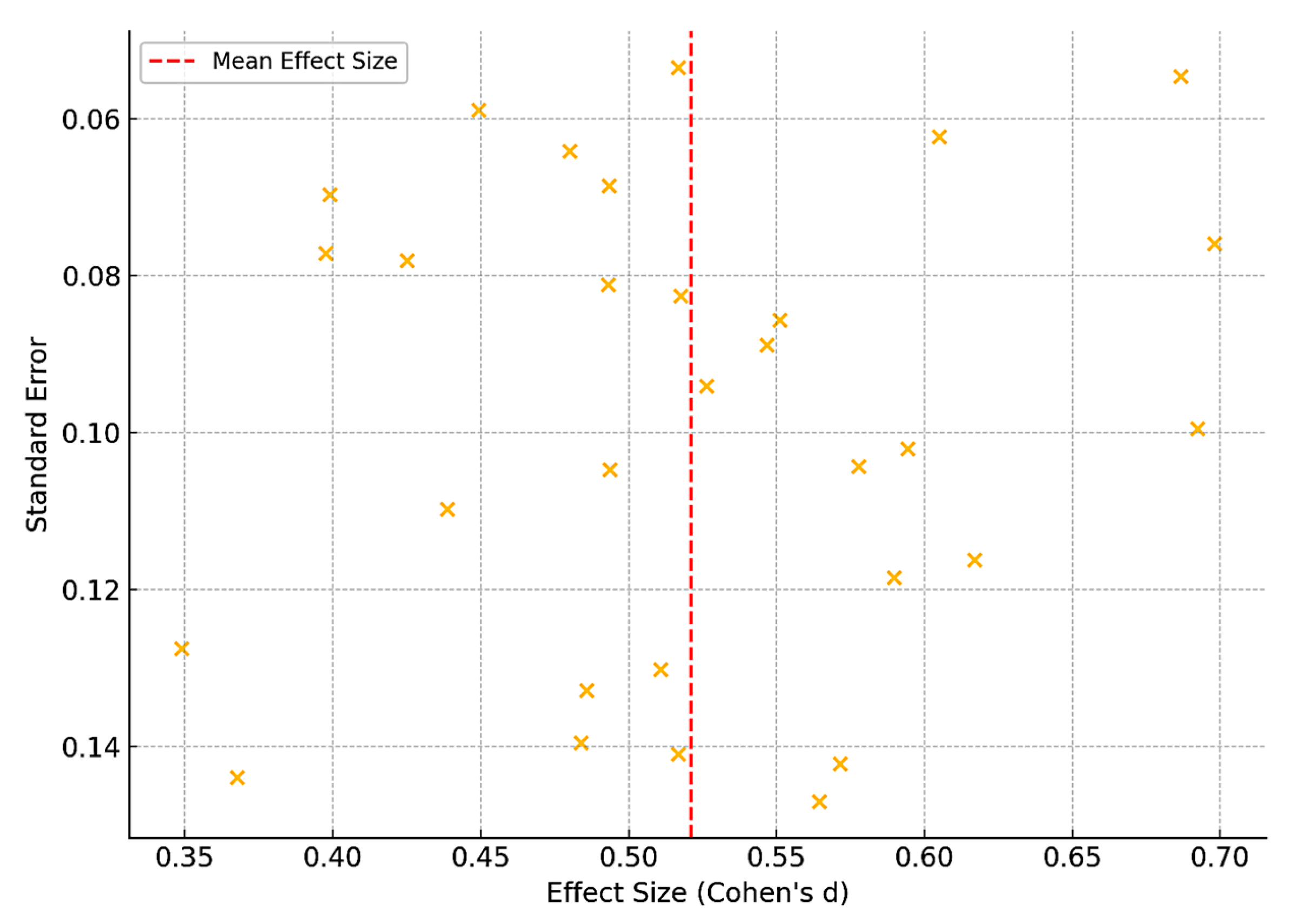

Visual inspection of the funnel plot showed reasonable symmetry across the three outcome variables, with datapoints clustering evenly around the central mean effect size. This pattern suggests a low likelihood of small-study effects or selective reporting, particularly for destination image and user engagement (

Figure 2).

This funnel plot visualizes the distribution of effect sizes for travel intention studies, thereby showing a reasonably symmetric pattern centered around the mean effect size, with some dispersion at higher standard errors—consistent with the minor publication bias detected in Egger’s test and the trim-and-fill adjustment.

6.5.2. Egger’s Regression Test

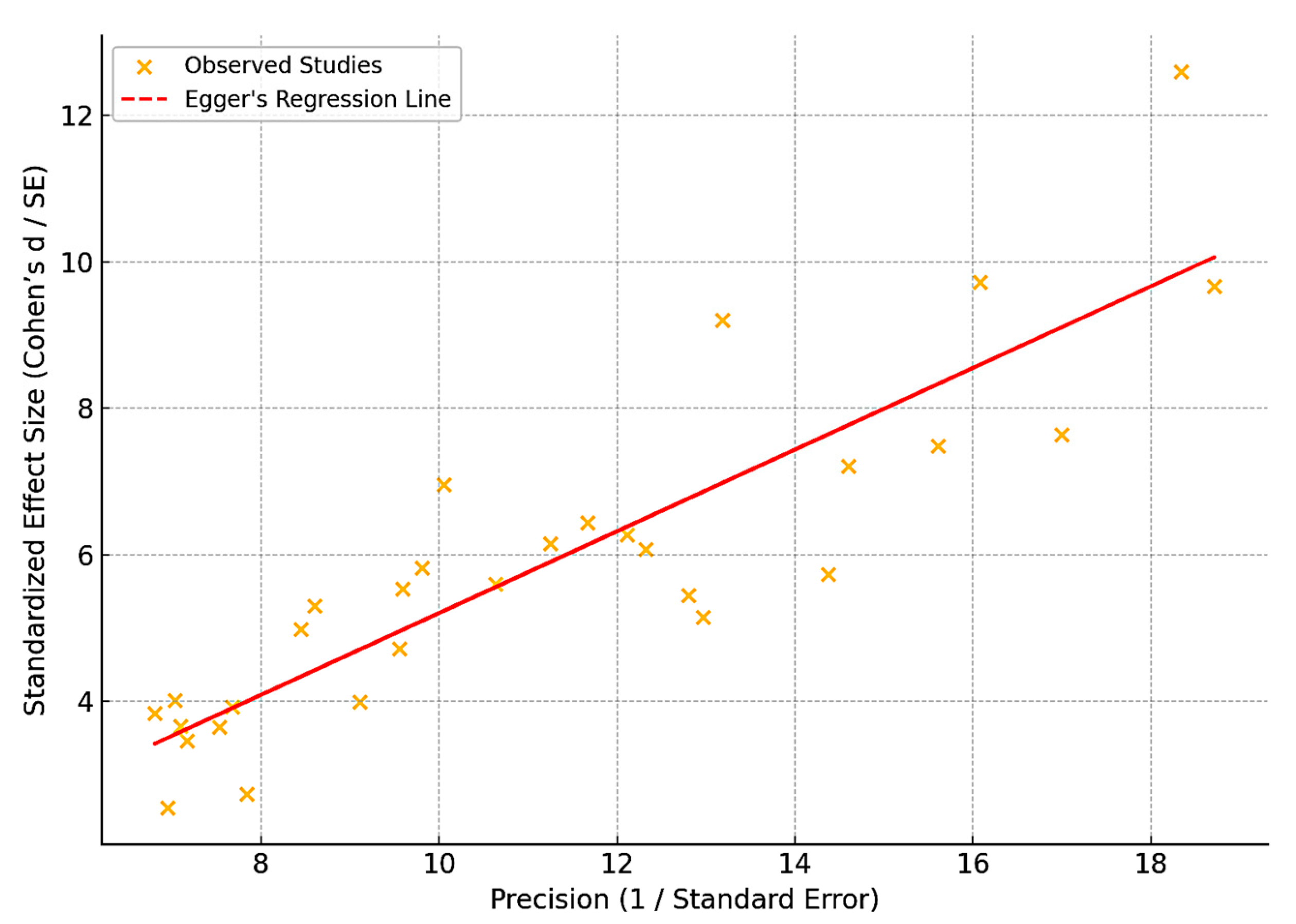

Egger’s regression test (

Figure 3) revealed statistical significance (

p < 0.05) for the travel intention outcome, indicating a potential small but nontrivial publication bias in this subset of studies. This suggests that studies reporting larger effects may be more likely to be published, especially those focusing on behavioral intentions.

The red line in Egger’s regression plot represents the regression line predicting the standardized effect size based on study precision. The slight slope in the line suggests a modest degree of asymmetry—supporting the earlier statistical indication of potential publication bias.

6.5.3. Trim-and-Fill Adjustment

Applying the trim-and-fill method led to a reduction in the estimated effect size for travel intention from d = 0.54 to d = 0.49. While this suggests the presence of missing studies with smaller or null results, the adjusted effect size remains statistically significant and practically meaningful, affirming the robustness of the original finding.

Table 3 presents the publication bias diagnostics; these checks provide confidence in the validity of the meta-analysis, while also acknowledging a modest tendency for stronger results to be more visible in the literature. This pattern is consistent with broader trends in publication bias across the social sciences, highlighting the need for future research to report null findings and use pre-registered, transparent methodologies. Findings presented in

Table 3 support the conclusion that while some degree of publication bias exists, especially for studies on travel intention, the overall findings remain robust and credible.

6.6. Implications and Limitations

The findings from this study affirm that social media plays a powerful role in shaping consumer behavior from a tourism marketing perspective. It significantly influences how travelers perceive destinations and form travel intentions, validating its status as a core mechanism in contemporary marketing strategies. However, a deeper look into the literature exposes several structural and conceptual limitations that hinder the field’s ability to evolve alongside the digital environment it studies.

A major concern is the emphasis given to quantitative performance metrics, such as likes, shares, or intentions expressed, at the cost of longer-term behavioral effects, such as destination loyalty, return visits, or sustained brand interaction. Without longitudinal assessments, this domain is devoid of the empirical evidence needed to investigate genuine effects across a sustained period.

A further gap is the lack of representation of newer platforms such as TikTok, BeReal, and Reddit. These sites are increasingly shaping conversations around travel, especially for younger generations; however, they are significantly underrepresented in the current corpus of tourism literature [

59].

A geographical and cultural bias exists, as the majority of these studies take place in settings found in the Global North. The results are, therefore, made less applicable to other forms of alternative tourism and do not consider local cultures that operate in different ways.

Lastly, ethical concerns such as data privacy, algorithmic biases, and social implications of AI-based personalization are not adequately addressed, although these are increasingly determining content visibility and consumption-related choices [

10].

To move forward, tourism marketing research should adopt more diverse methodologies, engage with underrepresented voices, and ask not just what works, but why, for whom, and at what cost.

7. Interdisciplinary Connections

Social media in tourism marketing does not exist in a disciplinary vacuum. On the contrary, the phenomena at its core—representation, influence, user behavior, platform dynamics—are deeply entangled with concepts and methods from across the social sciences, humanities, and information sciences. Yet, much of the current research remains siloed, drawing primarily from business and marketing traditions. To evolve, the field may well adopt an interdisciplinary lens.

This section highlights the key intersections with psychology, sociology, information science, communication studies, and ethics, revealing how each discipline can enrich the understanding and practice of digital tourism marketing.

7.1. Psychology: Cognition, Emotion, and Decision-Making

Tourism decisions are rarely made rationally. They are emotional, aspirational, and deeply subjective. Psychological theories—especially from consumer psychology and behavioral economics—help explain how visual stimuli, social validation, and emotional resonance shape perceptions of destinations [

40,

121].

The cognitive load theory, for example, can help explain why travelers gravitate toward simplified, image-rich content on such platforms as Instagram. Meanwhile, the theory of planned behavior has been used to model how attitudes formed online influence travel intentions [

122,

123].

However, the psychological dimensions of algorithmic influence, addiction, and dopamine-driven design in social platforms are under-researched in tourism. Future work should explore how psychological vulnerabilities are exploited or amplified by tourism marketing—especially among younger users.

7.2. Sociology: Identity, Belonging, and Social Capital

Sociological frameworks allow us to move beyond individual preferences and examine how social norms, group identity, and symbolic capital shape online travel behavior. Social media, particularly in tourism, is a site for performing identity—through check-ins, photos, and curated narratives [

123].

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of social capital can explain how influencers gain legitimacy and power, not just through content, but through their embeddedness in aspirational social networks. Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical theory is frequently invoked to interpret travel content as a staged performance [

124].

These insights are vital to understanding why people share travel content—not simply to inform, but to claim status, aesthetics, or lifestyle alignment. Yet, many tourism marketing studies treat content creation as purely instrumental, ignoring these deeper social functions.

7.3. Information Science: Algorithms, Data, and Platform Logic

The operation of social media platforms is governed by opaque, rapidly evolving systems of data collection, machine learning, and content curation. Information science provides the tools to critically assess how data are gathered, filtered, and monetized—shaping what users see, and therefore, how destinations are perceived.

Concepts such as algorithmic governance, platform capitalism, and data asymmetry help unpack the structural biases embedded in tourism marketing online [

16]. For instance, destinations with more content or higher engagement are algorithmically favored, reinforcing digital visibility for the already-visible.

Tourism researchers need stronger technical literacy and collaboration with data scientists to better understand these mechanisms and to critically engage with the platforms shaping the field itself.

7.4. Communication and Media Studies: Narrative, Representation, and Power

Media studies offer tools to examine how tourism narratives are constructed, circulated, and consumed. Influencer content, for example, functions as soft power—disguised persuasion embedded in lifestyle storytelling [

52]. Representation matters: the consistent portrayal of certain cultures as exotic, romantic, or consumable can reinforce colonial imaginaries [

7].

Moreover, the shift from audience to “produser” (producer + user) changes the dynamics of branding. Tourists are not passive recipients of marketing—they are active co-creators [

73], shaping brand meaning through interaction and content generation.

Yet many tourism marketing models still assume a top–down flow of influence. Media studies invite a more decentralized, discursive view of communication, acknowledging conflict, negotiation, and resistance within digital tourism discourse.

7.5. Ethics: Privacy, Equity, and Representation

The ethical dimensions of social media marketing are often treated as footnotes—if they appear at all. However, these issues are central to how the industry operates: Who gets represented? Whose data are collected? Who profits from user-generated content?

Tourism studies must engage with ethical theories from philosophy and media ethics to tackle questions of consent, digital exploitation, and representation. Influencer partnerships with indigenous communities, AI-curated recommendations that exclude low-income destinations, and the repackaging of user content without compensation all raise unresolved ethical questions.

Frameworks such as the ethics of care [

125] and the digital rights theory [

126] could help reframe tourism marketing not just as a commercial activity, but as a social contract between brands, platforms, and people.

7.6. Synthesis and Implications: Broader Academic Conversations

Social media in tourism marketing is inherently interdisciplinary, notwithstanding the plethora of studies that treat it as a subfield of business or communication studies. Beneath the surface of content strategies, engagement metrics, and platform analytics lie deeper questions about power, identity, technology, and ethics—questions that cannot be fully addressed through commercial or managerial frameworks alone. Social media does more than promote destinations; it shapes how places are seen, who is heard, and what types of travel are validated or excluded.

To remain relevant in a fast-changing digital landscape, researchers should move beyond the narrow lens of ROI and embrace a broader academic dialogue. This means drawing from sociology, media studies, cultural theory, psychology, and information science to unpack how platform algorithms, influencer dynamics, and user-generated content affect not just marketing performance, but cultural narratives and social realities.

Such an integrative methodology would bring together our comprehension of the frameworks, implications, and ethical issues surrounding digital tourism marketing. Through this methodology, it would facilitate deeper, culturally sensitive, and critically engaged research into the transnational dynamics shaping current traveling experiences. In effect, this shift is not just beneficial but is crucial for knowledge development according to methodological rigor and ethical responsibility in an era marked by algorithmic mediation and online exposure.

8. Sustainability Implications of Social Media and Metaverse Tourism Marketing

The transformative role of social media and emerging metaverse environments in tourism marketing goes beyond reshaping consumer behavior and destination image—it carries profound implications for sustainability. Social media-driven tourism often increases visibility but may contribute to overtourism and environmental degradation, notably through accelerated visitor flows to sensitive areas, as documented in such cases as Venice and Barcelona [

46,

66]. Socio-culturally, digital content frequently commodifies local identities, potentially exacerbating stereotypes or enabling authentic self-representation, depending on who controls narratives and visibility online [

9,

79]. Economically, while digital platforms can democratize market opportunities, they also risk deepening inequalities between digitally advanced destinations and less-connected regions, highlighting digital divides in global tourism economies [

10,

65]. Addressing these multifaceted sustainability implications requires responsible, interdisciplinary strategies prioritizing ethical considerations and long-term sustainable development [

19].

8.1. Environmental Sustainability