Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a major shift in project management practices, offering a unique opportunity to assess organizational resilience and sustainability. This study explores how project professionals in Quebec adapted to the early months of the pandemic, focusing on emergent practices in communication, decision making, stakeholder engagement, resource management, and scheduling. Using the most significant change (MSC) method, we collected and analyzed 114 stories from practitioners operating at both strategic and operational levels across multiple sectors. The findings reveal how project contributors reconfigured their practices to sustain value delivery amid disruption—adopting digital tools, modifying governance structures, and redefining engagement strategies. Operational contributors showed greater adaptability, while strategic actors experienced challenges with control and oversight. These stories illustrate not only reactive adaptations but also the foundations of more resilient and sustainable governance frameworks. By surfacing lived experiences and perceptions, this research contributes methodologically through its use of MSC and conceptually by linking crisis response with long-term sustainability in project contexts. Our study invites reflection on how temporary adaptations may evolve into embedded practices, reinforcing the interconnection between adaptability, resilience, and sustainability in the governance of project-based organizations.

1. Introduction

The year 2020 was indelibly marked by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a global crisis that triggered a profound health emergency with enduring consequences for societies and economies worldwide. In addition to the tragic loss of life, the pandemic ushered in an era of intense uncertainty, disrupting nearly all organizational operations and catalyzing a radical transformation in the ways work and projects are managed [1]. Project professionals were compelled to quickly reconfigure practices, adapt governance structures, and deploy digital technologies to maintain continuity in a highly constrained environment [2].

At the same time, the pandemic served as a real-time stress test for the sustainability of project organizations and their capacity to adapt. In this context, resilience and adaptability emerged not only as essential crisis response strategies but also as foundational dimensions of sustainable project management [3,4]. Resilience—defined as the ability to absorb shocks, reorganize, and maintain functionality—enables sustainability by supporting long-term performance, stakeholder well-being, and responsive governance under pressure [5]. For project organizations, embedding adaptability into communication, stakeholder engagement, and decision making is central to creating systems capable of weathering crises and sustaining value delivery [6]. Sustainable project management of this approach ensures that projects remain focused on results while adapting its governance.

Project management practices also underwent profound changes in this context. Some projects were forced to halt or delay activities, while others accelerated their timelines to deliver urgent solutions. Across sectors, digital technologies were rapidly adopted to sustain progress under public health restrictions [7]. While this transformation reflects a continuation of existing technological trends—such as the adoption of cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and mobile platforms [8,9]—it also revealed new competency demands for project managers, particularly in interpersonal and strategic domains [10]. In addition, the development of adaptive and inclusive governance practices emerged as critical to building resilience and enhancing sustainability.

This shift in project management practices raises important questions about the nature of governance, coordination, and decision making within projects, particularly regarding how these practices can contribute to long-term organizational sustainability and economic growth. These changes affect not only project managers at the operational level but also the senior leadership—including portfolio managers and project management officers—responsible for aligning strategy with execution. Understanding these transformations is crucial because they highlight how project practices and governance mechanisms adapted under crisis conditions. These adaptations offer valuable insights for developing governance models that are more resilient and capable of sustaining performance in the face of future disruptions [7]. This creates a clear research opportunity to explore how crisis-induced changes can be harnessed to enhance the long-term sustainability of project-based organizations.

Given the above call for research, the present study contributes to sustainability research by exploring how project professionals perceived and navigated significant changes in their work during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Employing the most significant change (MSC) method, we identified sustainable practices that enable project managers to withstand disruptions, such as COVID-19 pandemic. Through a sustainability lens, we herein examine how emergent practices of resilience and adaptability supported project continuity, stakeholder trust, and effective governance—core components of sustainable project management.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section presents our research background, focusing on resilience, adaptability, and sustainability in project management, and introduces the MSC method used for data collection and analysis. Sections three and four, respectively, describe the methodology and present the results. We conclude by discussing theoretical and practical contributions and suggesting avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

The COVID-19 pandemic has transformed many aspects of daily life, including education, healthcare, human relationships, and leisure [11,12]. Organizations, including those responsible for delivering projects, experienced a dramatic work transformation, as they were forced to adapt operations to new constraints such as lockdowns and social distancing [7]. Project environments were significantly affected by the sudden shift to remote work, accelerated digitalization, and heightened uncertainty. These challenges triggered substantial adaptations in project management practices, prompting reflection on how such transformations can foster more sustainable and resilient ways of working.

2.1. Work Transformation and COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a profound transformation in how project work is structured, coordinated, and governed. Among the most disruptive changes was the sudden shift to telework, which forced organizations to adapt project practices to virtual settings with little preparation [13]. While remote work has been associated with improved agility and productivity [14,15], it also led to increased stress, blurred boundaries between work and personal life, and feelings of isolation [16,17]. These challenges highlighted the need for stronger support systems and adaptive capacity within project-based organizations.

The accelerated use of digital technologies reshaped project coordination mechanisms. These systems had to be adapted, and new sociotechnical tensions emerged [18]. These changes went beyond tools—they required transformations in organizational routines, structures, and even governance principles [19,20]. For project teams, this meant relying heavily on virtual collaboration and asynchronous communication, often leading to misinterpretations, disengagement, or overload [21,22,23].

The pandemic also intensified longstanding tensions in project management—particularly between flexibility and control. Addressing these paradoxes requires ambidextrous approaches [24,25] and rethinking governance to balance monitoring with empowerment, in line with agency and stewardship theories [26]. More broadly, the crisis revealed the fragility of rigid governance models and underscored the value of adaptive leadership, inclusive coordination practices, and sustainability-oriented management [6].

2.2. Resilience and Sustainable Project Managemen

The field of project management was significantly disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Sudden shifts in priorities, work conditions, and stakeholder needs required project organizations to rapidly adapt. As Müller and Klein [7] emphasized, there is a pressing need for empirical research to understand how project, program, and portfolio management practices have adapted to crisis conditions—specifically to identify which of these changes were short-term responses and which might become part of the future project management practices. Bushuyev et al. [27] similarly advocated for adopting flexible and adaptive methodologies to navigate the heightened uncertainty and complexity triggered by such disruptions.

The literature on crisis management in projects offers a useful lens to understand these changes. Crises, as Simard and Laberge [28] noted, are dynamic and uncontrollable events that threaten organizational survival and demand immediate, strategic responses. These often involve launching new initiatives or reconfiguring existing projects to align with rapidly shifting priorities [29]. From a sustainability perspective, such disruptions can serve as inflection points—opportunities to adopt more adaptive, socially responsible, and environmentally sound practices. During the pandemic, for instance, project teams were forced to rethink stakeholder engagement, resource allocation, and team autonomy, all of which are closely associated with sustainable project delivery [6].

The intersection of sustainability, resilience, and adaptability has thus become central to emerging project management research. These three interrelated concepts help explain how project-based organizations can not only survive disruption but evolve to deliver long-term value in volatile environments. As Nüchter et al. [3] argued, resilience is increasingly seen not merely as a short-term coping mechanism but as a fundamental pillar of sustainable project management.

Sustainability, as a broader guiding principle, integrates both resilience and adaptability into a long-term value system. On one hand, it broadens traditional success metrics to encompass environmental responsibility, social inclusion, and long-term economic viability. On the other, it challenges top management to critically evaluate the sustainability of their practices and underlying philosophies [4,6]. In this framework, reactive and adaptive capabilities become strategic tools for achieving sustainable outcomes. For example, Trabucco and De Giovanni [5] illustrated how organizations that leveraged lean and digital tools during the pandemic enhanced both resilience and sustainability by maintaining operations, minimizing waste, and supporting employee well-being. Zahari et al. [30] illustrated that supply chains gain resilience and sustainability by enabling long-term survival through digital technologies, ensuring top management support, and information sharing during COVID-19. In this study, we define sustainable project management as the integration of economic, environmental, and social dimensions into project practices, aligned with long-term value creation and organizational adaptability. This definition draws on prior work by Sylvius et al. [6], who emphasized that sustainable project delivery requires not only responsible resource use and stakeholder inclusivity but also the ability to anticipate, absorb, and adapt to change.

Resilience is generally defined as the capacity of a system to absorb shocks, reorganize, and continue functioning under stress [29]. In project contexts, it implies flexible structures, empowered teams, and psychological safety to support rapid response and recovery [31]. Importantly, resilience also includes anticipatory capabilities—proactive efforts to identify and mitigate potential future disruptions [3]. Resilience plays a pivotal role in this conceptualization. It enables sustainability by fostering the capacity to maintain performance under pressure, respond to disruptions, and evolve governance structures accordingly. In this regard, resilience is not merely a short-term coping mechanism but a foundational component of sustainability in dynamic project environments [3].

Adaptability complements resilience by focusing on the learning capacity and behavioral agility of project actors. It involves dynamic resource allocation, iterative feedback loops, and decentralized decision making, which collectively enable projects to adjust to evolving conditions [27]. High adaptability facilitates the adoption of new tools and processes, making it possible for project teams to maintain momentum even during crises.

Together, these three dimensions offer a multidimensional perspective for understanding project effectiveness in turbulent times—highlighting the need for project governance models that are not only robust but also socially and ecologically attuned.

2.3. The Most Significant Change

The most significant change (MSC) method is a participatory approach to monitoring and evaluation that emphasizes the collection and analysis of qualitative data to assess the long-term impacts of programs and projects [32]. Originally developed by Davies and Dart [33] to evaluate international development initiatives in Bangladesh and grounded in a interpretivism paradigm [34], MSC has since been applied in a variety of organizational, community, and institutional contexts. It offers a way to capture significant changes as perceived by individuals at all levels affected by a project or program. This technique offers a valuable perspective for examining how project managers and their teams adapted during the pandemic. MSC assess what individuals experienced as a direct result of a specific context or event—in this case, the pandemic [35]. This method is particularly suited to this study because it reveals the nuanced and often unexpected transformation that project managers and teams underwent, such as alterations in their workflows, leadership approaches, and even organizational cultures, all of which might be overlooked by quantitative standardized analysis. It encourages participants to reflect deeply on their most meaningful changes, enabling a rich understanding of how their practices and perceptions evolved throughout the crisis.

At its core, MSC involves collecting stories of change from stakeholders impacted by an intervention. These stories describe the most significant change experienced and explain why the storyteller considers it significant. A selection panel—typically composed of project team members and key stakeholders—then reviews, analyzes, and discusses these stories to identify those that best represent the project’s outcomes [32]. This reflective process makes the MSC method particularly well suited for surfacing nuanced and meaningful changes that may not have been anticipated during the planning phase. Although this model was originally designed to improve a program or a project and to learn from it, it has been used to understand the stories that participants tell of themselves [36].

MSC shares conceptual similarities with the critical incident technique [37], especially in its focus on capturing transformative moments. However, unlike conventional evaluation approaches that rely heavily on quantitative indicators, MSC emphasizes narrative and subjective experience. It operates through a structured process guided by domains of change—broad thematic areas that help organize and interpret the collected stories [35]. This qualitative framework enables organizations to better understand the real impacts of their initiatives and how those impacts are perceived by different stakeholders.

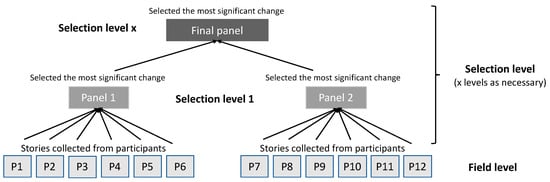

As shown in Figure 1 (adapted from [32]), the MSC process unfolds across several levels. At the field level, participants respond to the prompt: “During the last month, what do you think has been the most significant change related to the program/project?”. They are also asked to explain why the change is important to them. At the selection level, these stories are reviewed by stakeholders who respond to a second question: “Among all these changes, which one do you consider the most significant, and why?”. This layered evaluation highlights the stories that best reflect meaningful outcomes while encouraging dialogue across organizational levels. Feedback loops are an essential element of MSC, promoting mutual understanding of how project impacts are perceived and valued.

Figure 1.

The most significant change process (adapted from [32]).

Importantly, the MSC method also helps uncover unexpected outcomes—both positive and negative—that may not be captured by predefined metrics. This capacity to identify unanticipated results makes it especially useful for informing future strategic decisions and sustaining successful practices. As with prior applications in USA health care programs (e.g., Dave et al. [38]), using MSC in the pandemic context allows the research team to explore the personal impacts of crisis-driven adaptation by focusing on the values, challenges, and innovation responses that emerged in those temporary organizations. MSC can shed light on the complex, lived experience of project managers during crises and how these insights can inform future resilience and adaptative capacity in PM practices.

3. Method

To accomplish the research objective and inspired by Henning et al. [39], we adopted the MSC method to collect stories from project management professionals about the changes in project practices during the first confinement related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Quebec from March to August 2020. The research protocol adopted a mixed-method design to capture the perceptions and stories of project management professionals experiencing the first confinement during teleworking. A self-administered survey using a structured questionnaire was employed to obtain quantitative data from participants to identify the domains of change and qualitative data to collect stories about project management practice changes.

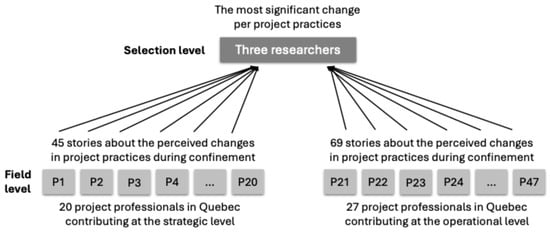

As shown in the Figure 2, we aimed to collect perceptions from professionals contributing to projects in different industries and using predictive, iterative, or hybrid approaches, including project managers, program managers, portfolio managers, project directors, or project manager officers. Their stories were then analyzed and categorized in domains of changes by a panel composed of researchers. They identified the most significant change for the most frequent domains of change (see Section 3.3).

Figure 2.

Adaptation of the most significant change for the research.

3.1. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out from 15 June to 5 August 2020, through an online self-administered questionnaire survey that includes three sections. The first and third sections allowed to collect quantitative data and the second collected qualitative data. The first section aimed to determine, using a 7-point Likert scale, the degree of change observed for the different knowledge areas defined in the PMBOK® project management knowledge guide [40] and those related to the project governance according to the domain of the standard for organizational project OPM [41]. The second section asked the respondent to select a maximum of three of the areas of project management where, according to their perception, they have observed most changes. In the Section 2, the participant was asked through an open question to describe the most significant change observed in the selected area: “During the COVID-19 pandemic confinement, what do you think has been the most significant change in project management and project governance practices? And why?”. Finally, a third section explored the socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, and years of experience) as well as information on the work context (job title and status, type of project, project approach, type of industry, scope of the project, etc.).

Given the constraints of conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to gather data from a time-constrained population, we adapted the canonical MSC method to a more streamlined format. Instead of multiple iterative rounds with stakeholder panels, we used a structured self-administered online survey to collect stories from a diverse pool of project contributors. This approach allowed us to efficiently reach a broad audience and gather a variety of experiences while still preserving the core intent of the MSC method—capturing change narratives from participants’ perspectives.

3.2. Participants

The selection of respondents was based on a non-probabilistic sampling, using researchers and professional associations networks. The target population was made up of all individuals occupying positions associated with project management, whether management positions or affiliate positions, employing an agile, waterfall, or hybrid project management approach. To maximize access to the target population, the collection strategy selected was to send the link to the survey through project management associations, including Agile Montreal, PMI-Montreal, PMI-Quebec, and GP-Québec. A first call was made through the PMI-Montreal and Agile Montreal communication channels on 15 June 2020 and a reminder on 15 July 2020.

A total of 113 participants answered the questionnaire, but later data analysis excluded the responses from participants who had not defined their perception about project management practice changes. As shown in the Table 1, 47 participants described at least one story: 58% of them contributed to projects at the operational level, such as project managers, program managers, agile coaches, or scrum masters, and 42% contributed to a higher project hierarchical level, such as portfolio managers, project directors, and project management officers. Additionally, 36% of participants contributed to engineering and construction projects, 30% to information technology projects, and 34% to business services projects.

Table 1.

Participants’ profile.

Participants were from sectors with varying degrees of exposure to pandemic-related disruptions. For instance, engineering and construction projects often faced site shutdowns or supply chain issues, while IT and business services organizations were more likely to shift quickly to remote collaboration. These contextual differences may have influenced the types of project practice changes reported and their perceived significance.

3.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were exported and analyzed using two different tools, namely IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27) to execute descriptive statistics analysis from quantitative data and Microsoft Excel to analyze the transcription of participants stories about perceived changes on project management practices during confinement. The participants’ stories were analyzed through thematic analysis (Miles, Huberman and Saldana 2014) [42], the results of which are presented by knowledge area as defined in the PMBOK® [40] for the project management practices and by domains defined by the standard for organizational project management [41] for project governance practices. We decided to use these references to classify and analyze the most significant change stories since these standards are widely used in temporary organizations [43]. In order to ensure the quality of our interpretation, two of the members of the research group who did not participate in the initial analysis validated story classification.

We adapted the MSC asking participants to describe one to three stories about the perceived project practices changes. As a result, 50% of participants added more than one story. As shown in Table 2, we analyzed 114 stories: 40% were described from participants contributing to projects on a strategic level and 60% on an operational level.

Table 2.

Number of stories collected for each domain of change.

3.4. Story Selection

In the original MSC approach, stakeholder panels review and iteratively select the most significant stories through discussion and consensus over several rounds [33]. In our adapted version, the MSC story selection process was conducted in a single round by a panel of three researchers involved in this study.

All the 114 stories were reviewed and categorized in fifteen change domains with an indication of the number of responses that related to each domain (see Table 2). Researchers then individually analyzed the story relevance for each domain by evaluating impacts (as described by the significant change stories) that are most important and relevant for project practices. This evaluation was not meant to prioritize significant change stories, but it was used to start a dialogue about the impact of the changes in project management practices and its relevance. Finally, researchers met to exchange their own evaluation, discuss them, and identify convergently the most significant change stories by domains of changes. The selected stories were then compared to evaluate significant differences between project contributors at the operational level and those at the strategic one.

These researchers independently coded the stories and achieved an initial agreement rate of approximately 85%. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus to ensure consistency in the thematic analysis. This decision was made to account for limitations in accessing a consistent and representative group of stakeholders for iterative deliberation during the pandemic. While this adaptation may have limited direct stakeholder engagement in the story selection phase, it allowed for a timely and systematic identification of the most representative change narratives by domain. To mitigate potential biases, the researchers performed independent evaluations before engaging in group deliberation to select the most significant stories for each domain.

4. Results

Most of the collected stories were related to domains of changes for project management practices (77% of the stories), where communication management was the domain of change with most stories. Furthermore, 33% of the collected stories were related to the project governance practices, where decision-making practices received the most stories. Participants did not describe stories for quality management, knowledge management, and competency management.

The following sections present the most significant stories for domains of change with higher collected story frequency: communication management practices (26 stories), decision-making practices (15), schedule management practices (15), stakeholders’ engagement practices (13), and resource management practices (11). We described the collected significant change stories in the function of two participants’ groups: the strategic level group (portfolio managers, senior management, and project management officers) and the operational level group (project managers, program managers, agile coaches, and scrum masters).

4.1. Communication and Management Practices

Communication management practices was the domain of change with the highest number of stories collected for both participants groups: the strategic level group with nine stories and the operational level group with 17 stories. The most significant change stories were generated by teleworking and communication and collaboration tools used during confinement. For several organizations undertaking projects, “teleworking was rather for international teams or in large regions”, but now, “all communications are done remotely”. Even public organizations that were reluctant to allow telework for some of their employees realized that there are some benefits to this new way of working. Indeed, many participants at the operational level reported increasing their productivity: “virtual meetings have allowed greater efficiency: less time wasted in travel, greater availability of workers who stayed at home”. As mentioned by a project manager, teleworking was possible because “different collaboration tools made it possible to better communicate with the stakeholders and team members”.

The use of digital tools to communicate and collaborate also generated changes in communication practices. For both groups, the most significant changes were a higher frequency of meetings, security and reliability information issues, and differences in digital tool uses and mastery, which caused delays in communication. However, both groups reported in their stories that there were few possibilities for informal communications: “[the] informal discussions [are no longer] possible, so we need to plan formal meetings to have more informal and personal exchanges” (a program manager). Also, they considered that exchanges became more complex because they did not have the means to observe and assess their counterpart’s gestures. As a project manager officer indicated, “the camera does not replace the look in the eyes of the interlocutor. Overall, we got used to it. But for more intense discussions or to build certain more strategic partnerships, it is less obvious”.

An important difference between both groups was related to the adaptation to these new communication practices. As shown in Table 3, the collected data indicate that participants at the operational level easily adapted to new tools and practices. They mentioned that project teams improved their collaboration and cohesion using collaborative technologies such as intranets and chats. However, participants at the strategic level reported that changes in the communications practices were significant, and they experienced important issues with their adoption. A project director stated that “some interlocutors are not prepared for a telework approach”. Exchanges between members were more complex if there were no clear rules for communicating: “this mode is difficult to manage: some people avoid speaking during meetings, or sometimes everyone tries to speak at the same time” (a portfolio manager).

Table 3.

Most significant change stories for communication management practices.

4.2. Decision-Making Practices

Decision-making practices was the second most common domain of change regarding stories collected for both participants’ groups and the only change domain with up to 10 stories for governance practices. The strategic level group reported seven stories and operational level group eight.

Participants in both groups reported that project governances “[have been] shaken as the usual committees are no longer used to make decisions” (a program manager). They described that steering committees focused on analyzing impacts from confinement, and decisions “oscillate between keeping the project running as usual and how to master remote work” (a project manager officer manager). For all the participants, decision-making practices changed since decisions “are [right now] made in multiple virtual meetings”, making it more difficult to have detailed discussions and trace arguments and actions. They also stated that making decisions virtually required greater transparency to project contributors and stakeholders.

As shown in Table 4, participants from the strategic group considered that the decision-making process became more complex because “decisions take longer to be made, especially when they involve consultation periods”. To facilitate communication, a portfolio manager asked project managers to “convey [information] more clearly and concisely”. The operation group stated that committees prioritized projects without enough information from the project managers and their teams. The latter indicates that containment reinforced a “top-down” type approach with little consultation, generating tensions between senior management and project teams. The results show that the operational level group considered that they had the capacity to help senior management make decisions since they had knowledge about the project scope and project environment.

Table 4.

Most significant change stories for decision-making practices.

4.3. Schedule Managament Practices

Schedule management practices was the third domain of change with the most stories collected for both participant groups: the strategic level group with six stories and the operational level group with nine stories. In this domain, we found no significative differences in perceptions for both groups.

Changes in schedule practices were generated either by project delays due to the confinement period or pressures to accelerate the completion of strategic projects, especially those considered urgent or mandatory to adapt organizations to the sanitary restrictions and teleworking. Participants in both groups reported delays in projects due to a variety of reasons. Project contributors, including team members, were not always available to do the work or took longer to do it because “some tools were not working well outside the internal network” (a scrum master). A project manager reported important delays because it was necessary “to limit the number of employees [on construction sites]” and to introduce new “security, sanitary and social distancing measures”.

Despite these challenges, participants in both groups said that they adopted measures to accelerate high-priority projects. A portfolio manager noted that “[schedule management] has been replaced by emergency management to support rapid deployment of the project”. As mentioned by a project manager, “the challenge is to engage suppliers to submit acceleration measures to limit overall delays in the schedule”. To deal with this concern, project manager offices updated their procurement practices and agreement to increase collaboration with suppliers to work more closely for strategy identification to fast-track and crash schedules while respecting human and material resources’ constraints.

4.4. Stakeholder’s Engagement Practices

Stakeholder engagement practices was the fourth domain of change with the most stories collected for both participants groups: the strategic level group with six stories and the operational level group with eight stories.

Both groups reported changes in stakeholder’s engagement practices. An important difference was observed between the mobilization of internal and external stakeholders. Several participants observed a strong cohesion between internal stakeholders (project manager, team members, and main contributors). As mentioned by a scrum master, there was a “strong mobilization” of teams and squads that were very “committed [to the project] at all levels”. On the other hand, it seemed that external stakeholders were difficult to mobilize. Customers or users had “difficulty adjusting” to new ways of working and new technologies because they were “overloaded” or “less available” or because they did not receive project information on time (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Most significant change stories for stakeholder engagement practices.

Even if both groups agreed with giving a higher priority to engage internal and external stakeholders during confinement and then adopting new approaches for keeping teams’ “momentum”, important differences were noticed for the acceptance of this change. The operational group reported a faster adaptation and obtaining positive impacts, such as “better cohesion” and “constant and fluid communication”. On the other hand, participants from the strategic group invested important efforts to engage stakeholders, such as constant meetings “by phone or videoconference”. However, they did not report positive outcomes: “some customers have difficulty to adjust themselves to the new project environment” (a portfolio manager).

4.5. Resources Management Practices

Resource management practices was the fifth domain of change with more stories collected for both participants groups: the strategic level group with three stories and the operational level group with eight stories. There were no significative differences in perceptions for both groups.

The most significant change described by both groups was related to the human resources affectation practices. Indeed, portfolio managers had to work closely with their project managers to reassign human resources to high-priority projects and/or urgent operations. Some organizations “have [for example] identified new priorities; thus, staff was allocated to these new initiatives to the detriment of projects already underway” (a portfolio manager). Participants also reported a decline in productivity and resource availability, which forced portfolio and program managers to re-evaluate organization capacity to execute projects.

The second most significant change identified by both groups was related to the project performance evaluation in general and, more specifically, for the team members. Project directors experienced important challenges to “supervise [their] teams” and measure the progress of their work against project priorities. Additionally, some project managers indicated that it was difficult to define performance targets in a changing context and with many constraints: “parenthood”, “slow adoption of digital tools”, “low employees’ supervision”, and “anxiety”, among others.

5. Discussion

From a sustainability perspective, the changes described by project professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic reflect emerging patterns of adaptive capacity and organizational resilience, which are essential for sustainable project practices and project governance. Practices around communication, stakeholder engagement, and team autonomy not only ensured operational continuity during a period of disruption but also supported more inclusive, flexible, and responsive governance—core attributes of sustainable project systems [6]. Just as viable supply chain management practices enhance organizational resilience and sustainability—through digital integration, top management support, and information sharing [44]—project practices evolved to embed flexibility, inclusion, and responsiveness.

As described by Müller and Klein [7], the pandemic prompted the emergence of new practices in temporary organizations, particularly in projects, programs, and portfolios, to comply with sanitary measures, maintain resilience, or rapidly launch new initiatives. Our findings reveal that organizations and project contributors updated their practices to cope with telework and confinement constraints—such as reduced resource availability, delayed schedules, and site closures—while seeking to sustain project performance. This demonstrates a capacity for real-time adaptation and responsiveness, key indicators of a resilient and learning organization.

Notably, the shift to telework—while enabling operational continuity—surfaced both benefits and challenges. On one hand, it fostered agility, empowered distributed teams, and enabled new modes of collaboration. On the other, it led to stress, miscommunication, digital fatigue, and a need to relearn interpersonal dynamics in virtual settings [14,15,16,17,18,23]. These contradictory effects emphasized the importance of organizational support systems, digital literacy, and soft skills like communication and collaboration. The transition revealed how digital tools are not neutral—they reshape power dynamics, interaction patterns, and, ultimately, governance practices.

In crisis contexts, communication becomes a cornerstone for sustaining performance and trust. Our results echo prior crisis research emphasizing the need for clear and inclusive communication across organizational levels [45]. Senior management and project management offices (PMOs) must not only establish protocols but also model and enable effective use of communication tools, ensuring psychological safety and shared understanding in uncertain environments.

As Fitzgerald et al. [46] underscored, transforming work systems requires attention to workers’ capabilities. The shift to remote collaboration increased the demand for both digital and soft skills [18]. In line with Pindek and Spector [47], our data highlight that individual contributors require training and support to effectively use new technologies and understand their role within transformed work systems.

Another key insight relates to the role of operational contributors in decision making. They expressed a desire to play a more active role in portfolio-level decisions, recognizing their on-the-ground knowledge as valuable for identifying environmental shifts and anticipating project impacts. This finding resonates with Wearne and White-Hunt’s [45] recommendation that decisions should be made where knowledge resides—an approach that enhances responsiveness and resilience. The importance of evidence-based and timely decision making emerged clearly in our findings, especially in the stories describing how project teams adapted during the crisis. Participants noted challenges with approval workflows and the need for greater autonomy and clarity [48].

However, perceptions of change diverged among stakeholders. Project and program managers generally showed a higher level of adaptability, while portfolio managers, PMO staff, and senior leadership appeared to struggle with modifying their governance and control practices. While operational teams demonstrated a high degree of flexibility and responsiveness—adapting workflows, communication practices, and priorities—strategic leaders encountered significant challenges in exercising control and governance remotely. This tension between agility on the ground and the need for oversight at the top highlights a structural misalignment that organizations must address to ensure coherence and resilience in times of disruption. As previously noted by Aubry [49], high-level governance structures can introduce rigidity into organizational routines and culture, which may inhibit adaptation during crises. This contrast suggests a misalignment between strategic and operational levels regarding the locus of control and decision-making authority.

This divergence was particularly clear in decision making. Strategic actors tended toward centralized control and accountability, while operational teams sought autonomy to tailor responses to contextual challenges. This governance tension reflects a classic agency vs. stewardship dynamic [26], requiring organizations to strike a balance between discipline and trust. The challenge mirrors the paradox between exploration and exploitation, calling for an ambidextrous mindset [24].

Ultimately, managing such contradiction is at the heart of sustainable and adaptable project governance. It requires leaders to navigate conflicting demands, enable multilevel learning, foster shared purpose, and manage constructive tensions. While difficult, this effort represents a path forward for organizations seeking to thrive amid complexity and uncertainty. These findings also echo Zahari et al. [30], who highlighted how digital tools and strategic coordination not only improve operational efficiency but also contribute to long-term resilience and competitive advantage. This supports our conclusion that sustainability in project governance is not only about environmental or ethical considerations but also about the strategic integration of adaptive capacities and innovative practices in response to disruption [50].

6. Conclusions

This study, conducted during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, explores how the crisis-induced measures—such as containment, physical distancing, and widespread teleworking—prompted significant changes in project management practices and governance structures. By adopting the most significant change (MSC) method, we systematically gathered and analyzed 114 narratives from professionals operating at both strategic and operational levels within project-based organizations. These stories revealed five main domains of change: communication, resource and schedule management, stakeholder engagement, and decision making. The pandemic functioned as a real-time governance laboratory, forcing organizations to experiment with alternative practices—such as decentralized decision making, rapid delegation, and flattened hierarchies—to maintain continuity in uncertainty. While many of these measures were initially adopted as emergency responses, our findings suggest that some have persisted beyond the immediate crisis, hinting at a longer-term shift in governance norms. Much like how wartime innovations often shape peacetime systems, these crisis-induced governance experiments may become part of a new managerial repertoire for navigating complexity and disruption.

Our findings contribute to answering the call for more empirical research on how global crises affect project environments [7]. Importantly, this research frames these transformations not simply as reactive adaptations but as pathways toward more sustainable and resilient project governance. The evidence shows that practices emerging from necessity—such as enhanced informal communication, flexible decision making, and participatory stakeholder engagement—may form the basis of a longer-term shift toward adaptive capacity and sustainability-oriented governance. These practices align with dimensions of sustainable project management, notably social inclusivity, responsive leadership, and responsible resource stewardship [6].

Notably, the MSC method allowed us to capture a diversity of perspectives across hierarchical levels, revealing both shared and divergent experiences. While commonalities were found in resource and schedule management, other domains varied by organizational position—highlighting how perceptions of change are shaped by one’s role within the system. Although rich in insight, the MSC approach does not provide detailed contextualization or causal analysis of these experiences. Future research could thus explore these tensions further—particularly between control and collaboration—as part of a broader inquiry into sustainable organizational transformation [26]. This is, to our knowledge, the first study using MSC to explore change in project governance practices during a global crisis. The method’s participatory nature represents a methodological contribution, offering a way to surface lived experiences and value-laden judgments about impactful changes—both of which are central to advancing sustainability-focused inquiry.

From a practical standpoint, this research invites project professionals and organizational leaders to reflect critically on the changes they experienced. The findings offer a retrospective lens through which to assess whether these crisis-induced adaptations have become embedded as part of a sustainable transformation. As organizations navigate ongoing uncertainty and complexity, learning from these emergent practices may help shape governance frameworks that are not only crisis-responsive but also resilient, inclusive, and future-ready.

To build on this work, future studies should aim to capture broader stakeholder perspectives—including clients, end-users, and community actors—and expand into underrepresented economic sectors. Comparative studies could also test the generalizability of these patterns across contexts. In doing so, the project management field can contribute more robustly to advancing the Sustainable Development Goals by cultivating governance models rooted in adaptability, equity, and long-term value creation. While this study identifies cross-sectoral trends in project management adaptation, it is important to recognize that certain sectors—such as IT or business services—may have been more agile in shifting practices due to their pre-existing digital maturity. In contrast, sectors like construction had to adapt under more constrained physical and logistical conditions. Future research could explore these differences in depth to better understand sector-specific pathways to resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.-T. and M.-D.P.; Methodology, M.-P.L.; Validation, A.R.-T. and M.-P.L.; Formal analysis, T.C.; Investigation, A.R.-T., M.-D.P. and J.D.; Data curation, J.D.; Writing—original draft, M.-P.L., M.-D.P. and T.C.; Writing—review & editing, A.R.-T.; Project administration, A.R.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Université du Québec à Montréal (protocol code 2021-3320 and June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Soto-Acosta, P. COVID-19 Pandemic: Shifting Digital Transformation to a High-Speed Gear. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020, 37, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeli, I.; Tsekouropoulos, G.; Vasileiou, A.; Hoxha, G. Benefits and challenges of teleworking for a sustainable future: Knowledge gained through experience in the era of COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüchter, V.; Abson, D.J.; Von Wehrden, H.; Engler, J.O. The concept of resilience in recent sustainability research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenia, S.; Dangelico, R.M.; Nonino, F.; Pompei, A. Sustainable project management: A conceptualization-oriented review and a framework proposal for future studies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucco, M.; De Giovanni, P. Achieving resilience and business sustainability during COVID-19: The role of lean supply chain practices and digitalization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.J.; Schipper, R.P. Sustainability in project management: A literature review and impact analysis. Soc. Bus. 2014, 4, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Klein, G. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Project Management Research. Proj. Manag. J. 2020, 51, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. The Project Manager of the Future: Developing Digital-Age Project Management Skills to Thrive in Disruptive Times; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- PMI. Artificial Intelligence: PMI’s Pulse of the Profession In-Depth Report; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D.; Lloyd-Walker, B. The future of the management of projects in the 2030s. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokazhanov, G.; Tleuken, A.; Guney, M.; Turkyilmaz, A.; Karaca, F. How is COVID-19 experience transforming sustainability requirements of residential buildings? A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Alshazly, H.; Idris, S.A.; Bourouis, S. Evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on society, environment, economy, and education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiter, S.; Kikulwe, D.; Danish, U.; Drynan, P.; Blackman, M. Navigating Challenges and Leveraging Technology: Experiences of Child Welfare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Societies 2024, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Kramer, K.Z. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, D.L.; Coombs, C.; Constantiou, I.; Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Gupta, B.; Lal, B.; Misra, S.; Prashant, P.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.M.; Mendoza, O.E.O.; Ramírez, J.; Olivas-Luján, M.R. Stress and myths related to the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on remote work. Manag. Res. 2020, 18, 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, A.; Crawford, L. Coping with stress: Dispositional coping strategies of project managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoek, R. Research opportunities for a more resilient post-COVID-19 supply chain—Closing the gap between research findings and industry practice. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroles, J.; Mitev, N.; de Vaujany, F.X. Mapping themes in the study of new work practices. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2019, 34, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.D.; Poinsatte-Jones, K.; Florin, M.V. Governance strategies for a sustainable digital world. Sustainability 2018, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuofa, T.; Ochieng, E. Working separately but together: Appraising virtual project team challenges. Team Perform. Manag. 2017, 23, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klitmøller, A.; Lauring, J. When global virtual teams share knowledge: Media richness, cultural difference and language commonality. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiadini, A.; Baldissarri, C.; Durante, F.; Valtorta, R.R.; De Rosa, M.; Gallucci, M. Together apart: The mitigating role of digital communication technologies on negative affect during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 554678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramurthy, C.; Lewis, M. Control and collaboration: Paradoxes of governance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushuyev, S.; Bushuiev, D.; Bushuieva, V. Project management during Infodemic of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Innov. Technol. Sci. Solut. Ind. 2020, 2, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Laberge, D. Development of a crisis in a project: A process perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 11, 806–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A. A framework for assessing project vulnerability to crises. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 12, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, M.K.; Zakuan, N.; Yusoff, M.E.; Mat Saman, M.Z.; Ali Khan, M.N.A.; Muharam, F.M.; Yaacob, T.Z. Viable Supply Chain Management toward Company Sustainability during COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, J.-T.; Berg, M.-E. A study of the influence of project managers’ signature strengths on project team resilience. Team Perform. Manag. 2020, 26, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dart, J.; Davies, R. A dialogical, story-based evaluation tool: The most significant change technique. Am. J. Eval. 2003, 24, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.; Dart, J. The Most Significant Change (MSC) Technique: A Guide to Its Use. 2005. Available online: https://ahi.sub.jp/eng/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/MSCGuide-1.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, S.; Lidstone, J. Evaluating leadership development using the Most Significant Change technique. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2013, 39, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Richard, P.; McCray, J. Evaluating leadership development in a changing world? Alternative models and approaches for healthcare organisations. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 26, 114–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.C. The Critical Incident Technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, G.; Noble, C.; Chandler, C.; Corbie-Smith, G.; Fernandez, C.S. Clinical scholars: Using program evaluation to inform leadership development. In Leading Community Based Changes in the Culture of Health in the US-Experiences in Developing the Team and Impacting the Community; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, J.E.; Rice, L.J.; Dani, D.E.; Weade, G.; McKeny, T. Teachers’ perceptions of their most significant change: Source, impact, and process. Teach. Dev. 2017, 21, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 6th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newton Square, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- PMI. The Standard for Organizational Project Management; Project Management Institute: Newton Square, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blomquist, T.; Farashah, A.D.; Thomas, J. Feeling good, being good and looking good: Motivations for, and benefits from, project management certification. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, O., Jr.; Fernandes, G.; Tereso, A. Benefits of Adopting Innovation and Sustainability Practices in Project Management within the SME Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitdewilligen, S.; Waller, M.J. Information sharing and decision-making in multidisciplinary crisis management teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, B.M.; Kruschwitz, N.; Bonnet, D.; Welch, M. Embracing Digital Technology: A New Strategic Imperative. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2013, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pindek, S.; Spector, P.E. Explaining the surprisingly weak relationship between organizational constraints and job performance. Hum. Perform. 2016, 29, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantović, V.; Vidojević, D.; Vujičić, S.; Sofijanić, S.; Jovanović-Milenković, M. Data-Driven Decision Making for Sustainable IT Project Management Excellence. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, M. Project management office transformations: Direct and moderating effects that enhance performance and maturity. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnley-Parry, I.M.; Farrier, A.; Dooris, M.; Whitton, J.; Manley, J. Organisations and Citizens Building Back Better? Climate Resilience, Social Justice & COVID-19 Recovery in Preston, UK. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).