Meeting 2030 Targets: Heat Pump Installation Scenarios in Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Italian Goals

- Air-source HPs: these extract thermal energy from the ambient air.

- Ground-source W/W HPs: these include systems that capture thermal energy from the ground.

- Hydrothermal HPs: these utilize thermal energy from water sources (groundwater, lakes, etc.).

- HPs can also be classified based on the type of fluid used for heat exchange within the building (indoor heat exchange).

- Water-based: These transfer heat through a hydraulic circuit that powers hot water radiators or underfloor heating systems. Examples include A/W-HPs and most GS-W/W-HPs.

- Air-based: as the name suggests, these use a wall-mounted unit to circulate warm air (or cool air if reversible).

3. Methodology for Estimating the Ambient Energy Produced by HPs

4. Climatic Classification of Italian Locations

5. Heat Pump Installations Based on Market Analysis

- Growth in demand and post-COVID context: The growing demand for residential air conditioners began in the post-COVID period and was further strengthened by increasingly hot summers, which led many users, even those who previously did not have an air conditioning system, to proceed with installation. The analysis of pre- and post-pandemic trends shows a clear increase in installations, confirming that changes in living habits and altered thermal comfort needs have significantly influenced this development.

- Impact of economic incentives: In recent years, for the purchase and installation of mono-split and multi-split systems, the most used financial incentives have been the so-called “Bonus Casa” and “EcoBonus”, which provide a 50% or 65% discount in the form of tax deduction. These incentives have provided good coverage of investments for A/A-HPs, especially considering their relatively low cost. Consequently, the driving effect of the so-called “Superbonus”, providing tax deductions of up to 110%, was marginal, highlighting how less costly incentives had a greater impact in supporting this kind of technology in the residential sector.

- Replacement of existing split systems: It is estimated that around 5.2 million mono-split systems (under 7 kWth) installed between 2004 and 2008 have reached their end-of-life, defined by regulations as 15 years, in recent years, forcing new installations. At the same time, only 3.9 million units were installed in the following five years (2009–2014). This suggests that, in the coming years, the replacement of existing systems now reaching the end of their life could have a moderate impact on the volume of new installations. It is therefore expected that in the next few years, the impact of replacing existing systems, which have reached the end of their life, will gradually decrease. Ref. [36] outlines the trends in the Italian HP market for 2024 by segment.

- Residential A/A-HPs (split systems): This segment experienced double-digit growth in 2024. The increase is mainly attributed to the replacement of older units installed between 2004 and 2009, as well as uncertainty regarding the future of the incentive schemes in 2025, which stimulated purchases towards the end of 2024.

- Residential A/W-HPs and W/W-HPs: Sales in this category have decreased by approximately 35% to 40%. The primary reason for this drop appears to be the end of the so-called “Superbonus” program, which had previously supported the market, bringing it back to 2021 levels. This highlights the strong dependence of this segment on government incentives.

- Hybrid systems: this segment experienced an even sharper decline, with an estimated drop of 70%, suggesting a potential loss of appeal following regulatory or incentive changes.

- HPs for DHW: this segment remained relatively resilient, with only a limited decline of 5%.

- Commercial sector (VRF, A/W-HPs, and W/W-HPs): Unlike the residential sector (excluding A/A-HP systems), the commercial sector continued to show growth, supported by stable demand from businesses and industries, largely independent of incentives. This confirms the different market dynamics between the residential sector and specific segments of the non-residential market.

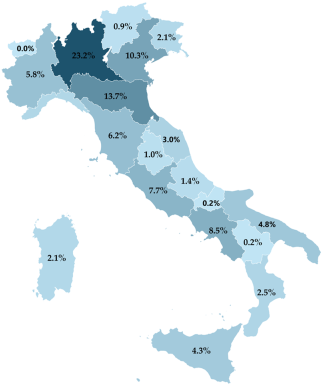

6. Territorial Breakdown: Climatic Location of the HP Stock

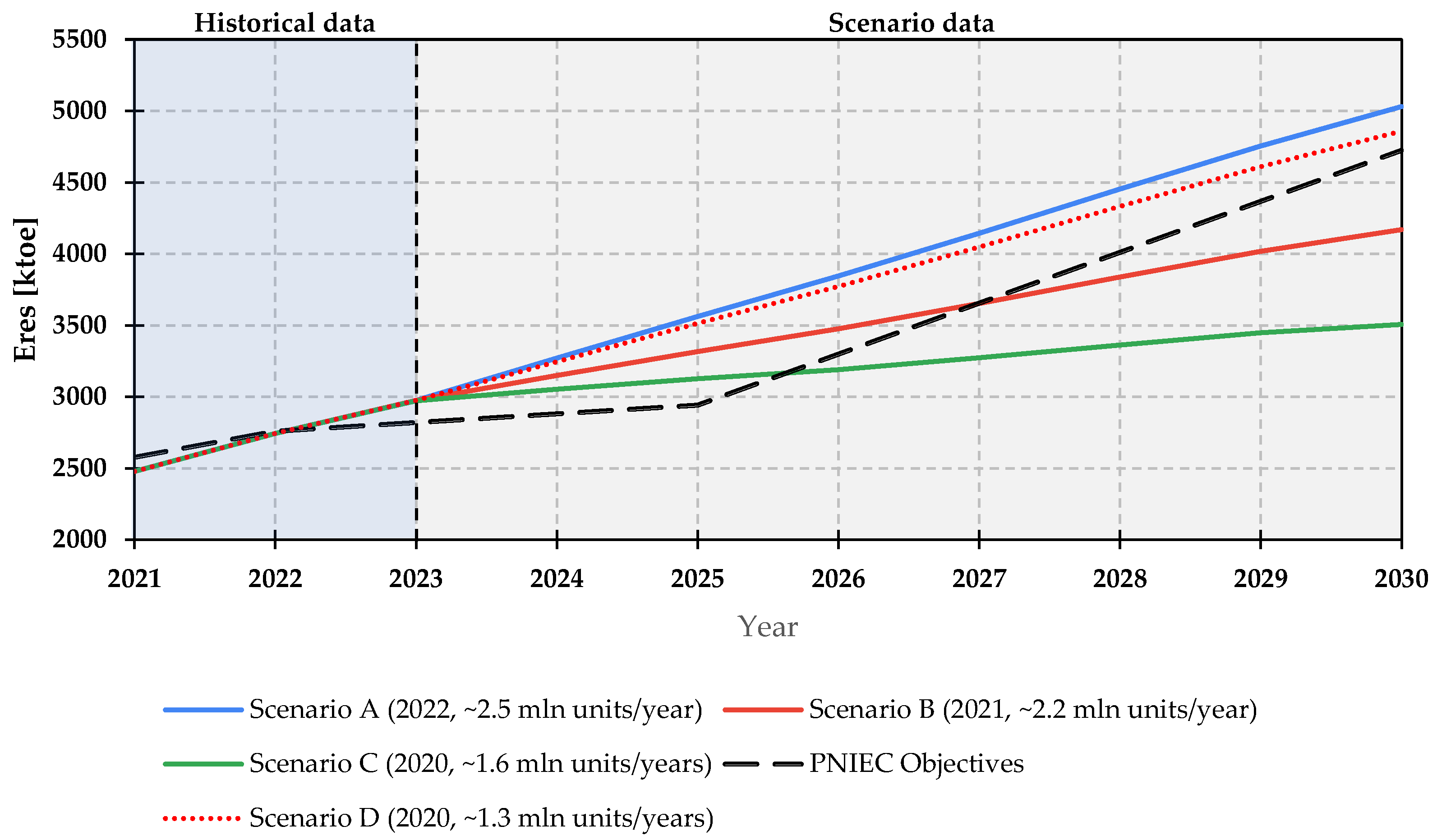

7. Scenarios for Achieving the PNIEC Objectives

8. Results

- Scenario A (2022): This scenario assumes an installation rate equal to that recorded in 2022, approximately 2.5 million units per year. This represents the highest installation level reached so far and is considered an ambitious goal but achievable with appropriate support policies. If maintained consistently until 2030, this pace would exceed the PNIEC target, ensuring 31.81 million HPs installed and an adjusted thermal capacity of 69.82 GWth.

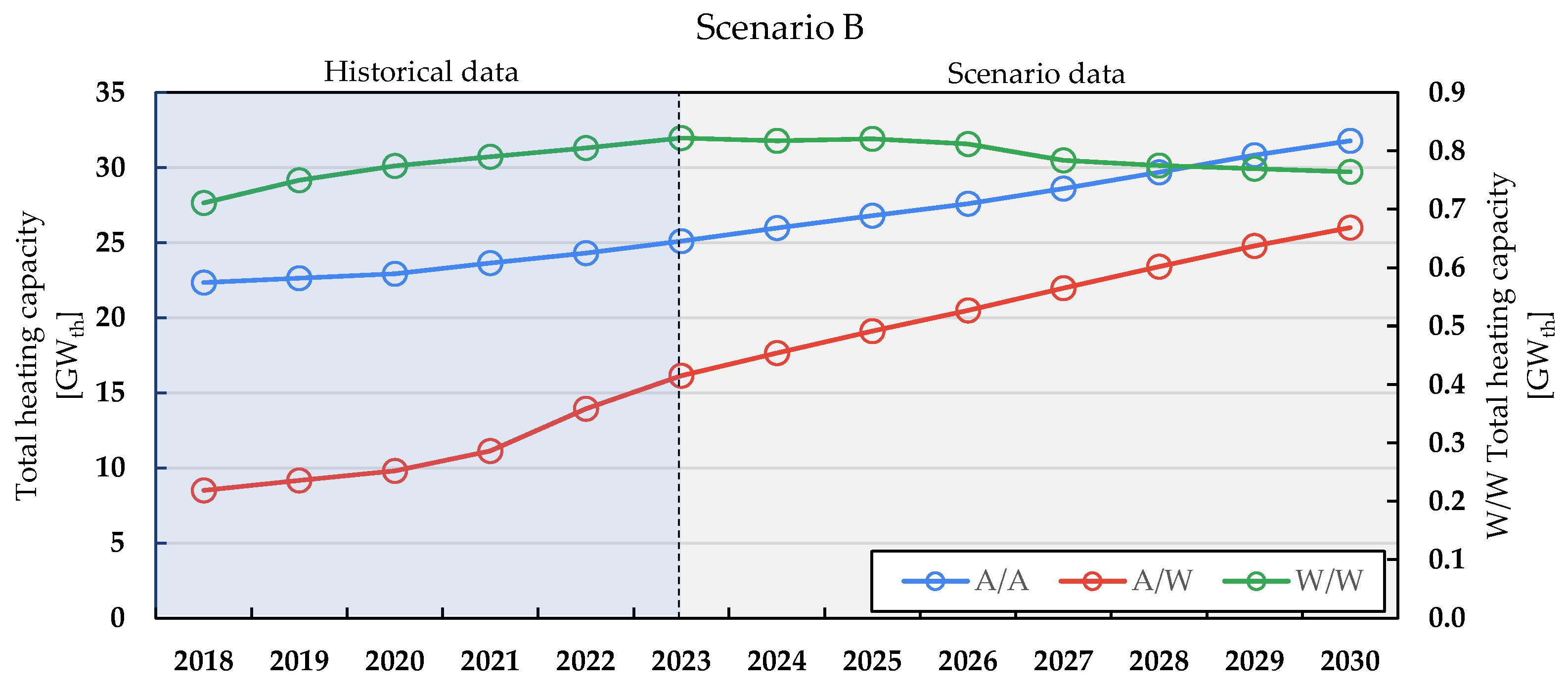

- Scenario B (2021): This scenario considers an installation rate of 2.2 million units per year, with an adjusted thermal capacity of 58.53 GWth. This growth level would be sufficient to meet the PNIEC targets until 2025, but it would be insufficient for 2030, where an additional 4 million units are required to meet the goal. To bridge the gap and reach the final target, an increase in the installation rate would be necessary from 2027 onward, with installations reaching approximately 3.2 million units per year in the last four years of the reference period.

- Scenario C (2020): This is the most conservative scenario, based on an annual installation rate of 1.6 million units, in line with the 2016–2020 average, and an adjusted thermal capacity of 49.85 GWth. This scenario would only meet the PNIEC targets for 2025 but would create a gap for the 2030 target, requiring about 8.9 million units. To catch up, the installation rate would need to nearly double from 2026 onward, reaching about 3.4 million units annually in the last five years.

- Scenario D (2020, with a different distribution of HPs): This additional scenario has been developed based on the assumption of a total installed heating capacity equal to the minimum value recorded in the three years preceding 2023, but with a different technological mix of HPs used in the residential sector. Specifically, the scenario involves a partial replacement of A/A units with A/W and W/W models while maintaining the same total heating capacity. Even under this configuration, the targets set for 2030 are achieved. It should be noted that, unlike for A/A systems, thermal capacity for A/W and W/W HPs has been fully considered without any adjustment, which facilitates the achievement of the targets. A detailed breakdown of the number of machines used by technology is provided in Appendix A.

9. Impact of HP Type in Future Scenarios

- In this scenario, an increase in the installation of A/W-HPs is assumed, replacing traditional boilers. This would have a direct impact on the decarbonization of both space heating and DHW production. A/W-HPs use hydronic heating systems (radiators, underfloor heating), offering a more seamless transition for users already accustomed to such systems. Furthermore, when properly sized for local climatic conditions, they can operate efficiently even in average and cold climates. A higher number of installed A/W-HPs, particularly when replacing fossil fuel boilers, would lead to a more substantial reduction in CO2 emissions in the residential sector, thus making a contribution to the PNIEC’s decarbonization objectives.

- This scenario promotes the installation of W/W-HPs, paired with low-enthalpy geothermal systems. These HPs take advantage of the more stable temperature of the ground or water sources, generally achieving higher Seasonal Performance Factors (SPFs) compared to A/A-HPs, especially in colder climates. Although their current adoption is limited, a wider deployment of this technology could significantly increase the share of renewable energy used for heating without requiring additional electricity consumption. However, their installation often entails higher initial investment costs and may require site-specific interventions. Despite recent national regulatory simplifications, large-scale adoption of this technology will require additional incentives and the removal of existing administrative and informational barriers.

10. Discussion

11. Limitations of the Study

12. Conclusions

- The continuity of incentives will be necessary to support market demand. Tax deductions have proven effective in stimulating the adoption of HPs, but policy uncertainty over their maintenance has unsettled the market. The scenarios presented have highlighted that, with the incentives foreseen in the 2025 financial law (covering the period until 2027), the goals can only be met up to the end of 2025. However, starting from 2026, a revision of support measures will be essential, with planning extended until 2030. Stable and long-lasting measures will therefore need to be implemented. To ensure the effectiveness of future policies, it will be necessary to implement stable, predictable, and diversified support mechanisms. In addition to tax deductions, alternative or complementary incentives could include direct grants, low-interest loans, and income-based subsidies, which are already widely used across the EU. For example, France applies a reduced VAT rate of 5.5% to a range of HP technologies and complements this with subsidies and targeted support. Italy could consider adopting similar fiscal measures to reduce upfront costs and ensure broader access to HP technologies. Moreover, rebalancing the tax burden on electricity bills and introducing flexible electricity tariffs—especially for users adopting renewable or smart systems—could improve the long-term economic appeal of HPs. Promoting flexible use (e.g., operation during off-peak hours) would also help consumers reduce costs and support grid efficiency.

- The evolution of regulations could play a decisive role. The European Green Deal and the directives on the decarbonization of the building sector are pushing toward the adoption of more efficient and environmentally friendly technologies. A significant impact on the HP sector is also expected from Regulation (EU) 2024/573 [55] on fluorinated greenhouse gases, which provides for the gradual phase-out of high-GWP HFCs, commonly used as refrigerants in these systems. The regulation also promotes the adoption of natural or low-climate-impact refrigerants, with important implications for the design, manufacturing, and installation of heat pump technologies. Adapting the Italian regulatory framework in line with these trends will be essential.

- The demand for electric HPs is expected to grow significantly in the coming years, particularly in the residential sector. In Italy, there are about 6 million non-condensing boilers, and replacing them with electric HPs would represent a strategic choice in the short to medium term for decarbonization. As stressed by [56], special attention should be given to the segment of HPs with capacity below 18 kWth for the residential sector. To avoid losing competitiveness and market share to countries that have already implemented support programs, it is essential to incentivize targeted investments and policies to support domestic production. A timely and effective intervention can foster the growth of this segment and strengthen the role of the Italian industry in the European energy landscape.

- The role of the industrial supply chain cannot be underestimated. In fact, national production accounts for around 59% of the main components used in HPs sold in Italy, while EU production covers around 90% of the European Union. However, focusing on HPs below 18 kW, which are essential for the decarbonization of the residential sector, Italian production represents less than 30% of units sold in the country. This limited national share highlights a strategic weakness in a sector that is expected to see significant expansion, as shown by our scenarios [56]. Furthermore, Italy’s dependence on industry is particularly pronounced for compressors, a key component recognized as a significant bottleneck in the supply chain for domestic systems (p < 50 kW). Increasing production and improving the availability of components and materials will be decisive to support the growth of installations without creating bottlenecks.

- Awareness and training are key elements in promoting the adoption of HPs. Many end users and sector operators are still not fully aware of the benefits of these technologies, making informational campaigns and professional development programs necessary.

- The results of Scenario D have demonstrated that achieving the PNIEC objectives is possible not only through a high total volume of installations (as in Scenario A) but also by focusing on a technological mix that prioritizes A/W-HPs and W/W-HPs. These technologies, due to their higher effective contribution to renewable heat production per installed unit, can compensate for a lower overall number of units installed, still ensuring the achievement of the objectives.

- Encouraging greater use of GS-W/W-HPs is also essential. Despite the simplifications introduced by the Italian Ministerial Decree of 30 September 2022 [57], this technology continues to be underutilized and struggles to find widespread adoption.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Prated,eff = Actual thermal capacity [GWth]; | |

| Prated,adj = Adjusted thermal capacity [GWth]. The adjustment factor has been applied to A/A-HP (mono-split and multi-split) used in residential settings. | |

| A/A-HP | Air-to-Air Heat Pumps |

| A/W-HP | Air-to-Water |

| ASHPs | Air Source Heat Pumps |

| DHW | Domestic Hot Water |

| EC | European Commission |

| EHPA | European Heat Pump Association |

| GS-W/W-HP | Ground-Source Air-to-Water Heat Pumps |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HDDs | Annual Degree Days |

| HTHP | High-Temperature Heat Pumps |

| LCOH | Levelized Cost of Heat methods |

| NGBs | Natural Gas Boilers |

| PNIEC | Italian National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RT&P | Roof Top and Package |

| SPBT | Simple Payback Time |

| SPFs | Seasonal Performance Factors |

| W/W-HP | Water-to-Water Heat Pumps |

Appendix A

| Type | Scope | Technology | Prated,eff | Eres | Annual Installation | Total HP Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kWth | GWh | Units | Units | |||

| AIR–AIR | R. | Mono-Split | P < 7 | 2362 | 669,726 | 14,784,643 |

| R. | Multi-Split | 1084 | 211,134 | 4,505,136 | ||

| AIR–WATER | R. | A/W | P < 10 | 13,512 | 243,251 | 2,043,680 |

| R. | A/W | 11 < P < 17 | 9609 | 105,698 | 939,133 | |

| R. | Hybrid * | 2872 | 18,618 | 396,429 | ||

| R. | A/W | 18 < P < 50 | 1762 | 3739 | 67,737 | |

| WATER–WATER | R. | W/W ** | P < 17 | 103 | 559 | 6487 |

| WATER–WATER | R. | W/W ** | 18 < P < 50 | 130 | 165 | 2726 |

| AIR–AIR | N.R. | Mono-Split | P > 7 | 5516 | 34,103 | 591,206 |

| N.R. | VRF | P < 19 | 1622 | 7529 | 120,576 | |

| N.R. | VRF | 20 < P < 30 | 2901 | 7264 | 117,393 | |

| N.R. | VRF | P > 30 | 5091 | 7643 | 123,295 | |

| N.R. | RT&P | P < 29 | 43 | 128 | 1837 | |

| N.R. | RT&P | 30 < P < 72 | 221 | 255 | 4540 | |

| N.R. | RT&P | 73 < P < 120 | 300 | 190 | 3519 | |

| N.R. | RT&P | P > 120 | 1139 | 399 | 6593 | |

| AIR–WATER | N.R. | A/W | 51 < P < 100 | 1972 | 1971 | 30,070 |

| N.R. | A/W | 101 < P < 200 | 2008 | 884 | 14,556 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 201 < P < 350 | 1545 | 352 | 6086 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 351 < P < 500 | 940 | 136 | 2368 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 501 < P < 700 | 721 | 86 | 1329 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 701 < P < 900 | 205 | 17 | 278 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 901 < P < 1200 | 59 | 0 | 65 | |

| WATER–WATER | N.R. | W/W | 51 < P < 100 | 123 | 69 | 1278 |

| N.R. | W/W | 101 < P < 200 | 214 | 62 | 1132 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 201 < P < 350 | 267 | 52 | 750 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 351 < P < 500 | 103 | 12 | 184 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 501 < P < 700 | 82 | 10 | 108 | |

| Total [GWh] | 56,506 | - | ||||

| Total [ktoe] | 4858.7 | - | ||||

| Total (units) | - | 1,314,052 | 23,773,134 | |||

References

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Heat Pumps. World Energy Outlook Special Report. 2022. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/heat-pumps_en (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council Progress on Competitiveness of Clean Energy Technologies. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022DC0643 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Council of the European Union. Fit for 55: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fit-for-55/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document—Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the regions. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=SWD%3A2022%3A230%3AFIN (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- European Heat Pump Association. European Heat Pump Market and Statistics Report 2023. Available online: https://www.ehpa.org/news-and-resources/publications/european-heat-pump-market-and-statistics-report-2023/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Lyons, L.; Georgakaki, A.; Kuokkanen, A.; Letout, S.; Mountraki, A.; Ince, E.; Shtjefni, D.; Joanny, G.; Eulaerts, O.D.; Grabowska, M. Clean Energy Technology Observatory: Heat Pumps in the European Union—2022 Status Report on Technology Development, Trends, Value Chains and Markets; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Heat Pump Accelerator Platform. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/heat-pumps/heat-pump-accelerator-platform_en (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission—Green Deal Industrial Plan. Net-Zero Industry Act. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/green-deal-industrial-plan/net-zero-industry-act_it (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission. Heat Pumps Action Plan: Online Consultation Launched by the Commission to Accelerate Roll-Out Across E.U. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/news/heat-pumps-action-plan-online-consultation-launched-commission-accelerate-roll-out-across-eu-2023-06-07_en (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Peñaloza, D.; Mata, É.; Fransson, N.; Fridén, H.; Samperio, Á.; Quijano, A.; Cuneo, A. Social and Market Acceptance of Photovoltaic Panels and Heat Pumps in Europe: A Literature Review and Survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Gaur, A.; Fitiwi, D.Z.; Curtis, J. Heat Pumps and Our Low-Carbon Future: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Feng, W.; Luo, M.; You, K.; Ma, M.; Jiang, R.; Leng, J.; Sun, L. Techno-Economic Analysis of Residential Building Heating Strategies for Cost-Effective Upgrades in European Cities. iScience 2023, 26, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Guire, J.; Balyk, O.; Petrović, S.N.; Moran, P.; Gallachóir, B. Ó; Daly, H. Advancing Cost-Optimal Residential Decarbonisation Pathways: An Examination of Heat Pumps and Thermal Efficiency. Energy Build. 2024, 317, 114383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meles, T.H.; Ryan, L. Adoption of renewable home heating systems: An agent-based model of heat pumps in Ireland. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, E.; McKenna, R.; Fehrenbach, D.; Fichtner, W. A model-based assessment of climate and energy targets for the German residential heat system. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3151–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Gaete-Morales, C.; Kirchem, D.; Schill, W. Power sector benefits of flexible heat pumps in 2030 scenarios. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Wolf, T.; Wapler, J.; Hollinger, R.; Madani, H. Model-Based Flexibility Assessment of a Residential Heat Pump Pool. Energy 2017, 118, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaßen, G.; Kavvadias, K.; Jiménez Navarro, J.P. The Decarbonisation of the EU Heating Sector through Electrification: A Parametric Analysis. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari, M.; Keogh, D.; De Rosa, M.; Finn, D.P. Technical and Economic Assessment of a Hybrid Heat Pump System as an Energy Retrofit Measure in a Residential Building. Energy Build. 2023, 295, 113256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masternak, C.; Meunier, S.; Reinbold, V.; Saelens, D.; Marchand, C.; Leroy, Y. Potential of Air-Source Heat Pumps to Reduce Environmental Impacts in 18 European Countries. Energy 2024, 292, 130487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiou, T.; Fragkos, P.; Zisarou, E. Decarbonising the EU Buildings|Model-Based Insights from European Countries. Climate 2024, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradziuk, P.; Siudek, A.; Klepacka, A.M.; Florkowski, W.J.; Trocewicz, A.; Skorokhod, I. Heat Pump Installation in Public Buildings: Savings and Environmental Benefits in Underserved Rural Areas. Energies 2022, 15, 7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trypolska, G.; Gradziuk, P.; Semeniuk, A.; Podolets, R.; Diachuk, O. Advancing Heat Pump Adoption in Ukraine’s Low-Carbon Energy Transition. Energies 2024, 17, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.; Csontos, C.; Harmat, Á.; Csüllög, G.; Munkácsy, B. Heat Consumption Scenarios in the Rural Residential Sector: The Potential of Heat Pump-Based Demand-Side Management for Sustainable Heating. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.D.; Crawley, J.; Lomas, K.J.; Buswell, R.A. Predicting Future GB Heat Pump Electricity Demand. Energ. Build. 2023, 286, 112917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Irving, R. Possible Effects of Future Domestic Heat Pump Installations on the UK Energy Supply. Energ. Build. 2014, 84, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katris, A.; Turner, K.; Calvillo, C.F.; Zhou, L. The Importance of Heat Pump Cost Reduction and Domestic Supply Chain Development in the Presence of Persisting Energy Price Shocks. Energy Strat. Rev. 2024, 55, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, O.; Yaramenka, K.; Mata, É.; Burgoa Francisco, F.; Gabaldon Moreno, A.; Lidfeldt, M.; Verdugo González, F. Positive Climate and Health Impacts from Upscaled Use of Heat Pumps and Solar Panels in Technology Packages in EU-27 by 2050. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 44, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efkarpidis, N.A.; Vomva, S.A.; Christoforidis, G.C.; Papagiannis, G.K. Optimal Day-to-Day Scheduling of Multiple Energy Assets in Residential Buildings Equipped with Variable-Speed Heat Pumps. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Siam, M.R.K.; Bond, T.C. A Critical Review of Heat Pump Adoption in Empirical and Modeling Literature. iScience 2025, 28, e111666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlavinka, A.N.; Mjelde, J.W.; Dharmasena, S.; Holland, C. Forecasting the Adoption of Residential Ductless Heat Pumps. Energy Econ. 2016, 54, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimian Rizi, B.; Lee, J.; Heidarinejad, M. Trends for the Installation of Heat Pumps in the US Residential Buildings. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 73, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, A.; Martin, H.; Hoz, J.d.l.; Rubio, J. A Review of Worldwide Strategies for Promoting High-Temperature Heat Pumps. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.H.; Abdullah, B.; Ahmad, M.W.; Rostami, A.; Cullen, J. Heat Transition in the European Building Sector: Overview of the Heat Decarbonisation Practices through Heat Pump Technology. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 48, 101630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security. National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan. 2024. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/sites/default/files/PNIEC_2024_revfin_01072024.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Heat Pump Association. Why Did Heat Pump Sales Drop in 2024? 2025. Available online: www.ehpa.org/news-and-resources/news/why-did-heat-pump-sales-drop-in-2024/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Decision of 1 March 2013 Establishing the Guidelines for Member States on Calculating Renewable Energy from Heat Pumps from Different Heat Pump Technologies Pursuant to Article 5 of Directive 2009/28/ECof the European Parliament of the Council (Notified Under Document C(2013) 1082) Text with EEA Relevance. 2.0.1.3./.1.1.4./.E.U; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec/2013/114(1)/oj/eng (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2009/28/EC of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC; (Text with EEA Relevance); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2009; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=celex:32009L0028 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 811/2013 of 18 February 2013 Supplementing Directive 2010/30/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to the Energy Labelling of Space Heaters, Combination Heaters, Packages of Space Heater, Temperature Control and Solar Device, and Packages of Combination Heater, Temperature Control and Solar Device; (Text with EEA Relevance); Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32013R0811 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission. JRC Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS). Joint Research Centre, European Commission: Italy21024. Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Presidential Decree No. 412 of 26 August 1993. Regulations Establishing the Minimum Energy Performance Requirements for Buildings and Thermal Equipment. Official Gazette of the Italian Republic, 1 November 1993.

- European Commission Cooling and Heating Degree Days by Country—Monthly Data. Eurostat. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/qpz4216lvn91t1vf3v2nkq?locale=en (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Eurostat. SHARES Tool Manual. European Commission. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/38154/4956088/SHARES+tool+manual-2021.pdf/11701ebe-1dae-3b00-4da4-229d86d68744?t=1664793455773 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Comuni Italiani. Province Italiane per Abitanti. Available online: https://www.comuni-italiani.it/provincep.html (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Assoclima. Statistical Survey by Assoclima, Edited by Anima Research Office, on the Market for Components for Air Conditioning Systems. Anima. Available online: https://www.anima.it/associazioni/elenco/assoclima/attivita/pubblicazioni/studi-di-mercato.kl (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- EurObserv’ER. Heat Pumps Barometer 2024; EurObserv’ER: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.eurobserv-er.org/heat-pumps-barometer-2024/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast). Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; pp. 1–60. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj/eng (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Commission. Communication on the Gradual Phase-out of Financial Incentives for Single Heating Systems Powered by Fossil Fuels under the Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings. Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:C_202406206 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). Energy Performance of Buildings. Heating Systems and Cooling Systems in Buildings—Part 1: Economic Evaluation Procedure for Building Energy Systems. Module M1-14; EN 15459-1:2018; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISPRA. Italian Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2021 National Inventory Report 2023; ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files2023/pubblicazioni/rapporti/rapporto_383_2023.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Gestore dei Servizi Energetici (GSE). Thermal Sector—National Monitoring of Renewable Energy; Gestore dei Servizi Energetici (GSE): Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.gse.it/dati-e-scenari/monitoraggio-fer/monitoraggio-nazionale/settore-termico (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- European Heat Pump Association (EHPA). Market Data; EHPA: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://www.ehpa.org/market-data/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Assoclima. Libro Bianco sulle Pompe di Calore—Quarta Edizione [White Paper on Heat Pumps—Fourth Edition]; Assoclima: Milan, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.anima.it/kdocs/2097876/libro_bianco_sulle_pdc_quarta_ed_agosto_2023.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Roca Reina, J.C.; Carlsson, J.; Volt, J.; Toleikyte, A. Alternatives for Decarbonising High-Temperature Heating Facilities in Residential Buildings. Energies 2025, 18, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/573 of 7 February 2024 on Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases, Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 517/2014. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/573/oj/eng (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Assoclima; TEHA Group. The Role of Heat Pumps in Italy: State of the Art Development Opportunities 2025. Available online: https://www.anima.it/kdocs/2174900/executive_summary_eng.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Ministero della Transizione Ecologica. Decree of 30 September 2022, Prescriptions for the Installation of Heat Production Systems from Geothermal Resources, Intended for Heating and Cooling Buildings and Measures for the Simplification of the Installation of Such Systems. Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana, No. 240, 30 September 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/10/14/22A05770/SG (accessed on 18 March 2025).

| Year | 2021 | 2022 | 2025 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerator | 11,061 | 10,626 | 12,490 | 17,634 |

| Gross heat production from RES | 373 | 373 | 519 | 537 |

| Final RES consumption for heating and cooling | 10,688 | 10,252 | 11,970 | 17,097 |

| of which biomethane (1) | 0 | 0 | 996 | 3186 |

| of which other bioenergy (1) | 7477 | 6827 | 7018 | 7464 |

| of which solar | 247 | 263 | 494 | 699 |

| of which geothermal | 115 | 110 | 167 | 208 |

| of which hydrogen | 0 | 0 | 12 | 315 |

| of which ambient energy | 2849 | 3052 | 3284 | 5225 |

| Denominator—final gross consumption in the thermal sector | 57,068 | 51,538 | 50,884 | 49,159 |

| Renewable energy share (FER-C) (%) | 19.40% | 20.60% | 24.50% | 35.90% |

| Possible contribution from waste heat and renewable electricity (flexibility) (2) | 450 | |||

| Renewable energy share with flexibility (%) | 36.50% |

| Climatic Conditions | Reference Location | Average Annual Temperature | Average Annual Solar Irradiance | Total Annual Solar Irradiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | W/m2 | kWh/m2 | ||

| Cold | Helsinki | 7.01 | 112.8 | 988 |

| Average | Strasbourg | 11.4 | 139.5 | 1222 |

| Hot | Athens | 18.1 | 203.9 | 1786 |

| Climatic Conditions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold | Average | Warm | |||||

| HP Energy Source | Energy Source Distribution Medium | HHP | SPF SCOPnet | HHP | SPF SCOPnet | HHP | SPF SCOPnet |

| Air-source energy | air/air | 1970 | 2.5 | 1770 | 2.6 | 1200 | 2.7 |

| air/water | 1710 | 2.5 | 1640 | 2.6 | 1170 | 2.7 | |

| air/air (reversible) | 1970 | 2.5 | 710 | 2.6 | 120 | 2.7 | |

| air/water (reversible) | 1710 | 2.5 | 660 | 2.6 | 120 | 2.7 | |

| exhaust air/air | 600 | 2.5 | 660 | 2.6 | 760 | 2.7 | |

| exhaust air/water | 600 | 2.5 | 660 | 2.6 | 760 | 2.7 | |

| Geothermal energy | ground/air | 2470 | 3.2 | 2070 | 3.2 | 1340 | 3.2 |

| ground/water | 2470 | 3.5 | 2070 | 3.5 | 1340 | 3.5 | |

| Hydrothermal heat | water/air | 2470 | 3.2 | 2070 | 3.2 | 1340 | 3.2 |

| water/water | 2470 | 3.5 | 2070 | 3.5 | 1340 | 3.5 | |

| Italian Region | Climatic Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold | Average | Warm | ||||

| Provincial Capitals | Population | Provincial Capitals | Population | Provincial Capitals | Population | |

| Abruzzo | 0 | 0 | 1 | 301,910 | 3 | 1,020,337 |

| Basilicata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 570,365 |

| Calabria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1,965,128 |

| Campania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5,839,084 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 1 | 448,899 | 8 | 3,999,942 | 0 | 0 |

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | 1 | 531,466 | 3 | 686,406 | 0 | 0 |

| Lazio | 0 | 0 | 1 | 157,420 | 4 | 5,740,704 |

| Liguria | 0 | 0 | 1 | 850,071 | 3 | 715,236 |

| Lombardy | 2 | 1,050,296 | 10 | 8,968,510 | 0 | 0 |

| Marches | 0 | 0 | 2 | 515,501 | 2 | 648,973 |

| Molise | 0 | 0 | 1 | 85,805 | 1 | 224,644 |

| Piedmont | 5 | 3,379,048 | 3 | 1,013,478 | 0 | 0 |

| Apulia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4,063,888 |

| Sardinia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1,653,135 |

| Sicily | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5,056,641 |

| Tuscany | 0 | 0 | 3 | 996,924 | 8 | 3,119,094 |

| Trentino-South Tyrol | 2 | 1,062,860 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Umbria | 0 | 0 | 1 | 660,690 | 1 | 228,218 |

| Aosta Valley | 1 | 126,883 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veneto | 1 | 205,781 | 6 | 4,701,748 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 13 | 6,805,233 | 40 | 22,938,405 | 57 | 30,845,447 |

| Percentage distribution | 11.8% | 11.2% | 36.4% | 37.9% | 51.8% | 50.9% |

| Quantity HP | Total Installed Thermal Capacity | |

|---|---|---|

| Units | GWth | |

| TOTAL | 21,087,668 | (110.31) 39.04 ** |

| Residential | 20,172,558 | (88.68) * 17.40 ** |

| A/A-HP | 19,352,532 | (80.36) * 9.08 ** |

| A/W-HP | 810,975 | 8.14 |

| W/W-HP | 9051 | 0.19 |

| Not residential | 915,109 | 21.63 |

| A/A-HP | 872,537 | 15.22 |

| A/W-HP | 39,071 | 5.79 |

| W/W-HP | 3501 | 0.62 |

| Type | Unit in Operation | % | Prated,eff GWth | % | Prated,adj GWth | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/A-HP | 20,225,070 | 95.9% | 95.6 | 86.60% | 24.3 (*) | 62.30% |

| A/W-HP | 850,046 | 4.0% | 13.9 | 12.60% | 13.9 | 35.70% |

| W/W-HP | 12,552 | 0.1% | 0.8 | 0.70% | 0.8 | 2.10% |

| Total | 21,087,668 | 100.0% | 110.3 | 100.00% | 39.04 | 100.00% |

| Stock (A) | Stock (B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|  | ||

| Application | Type and Size | Application | Type and Size |

| A/A–R. | Mono-Split (Prated < 7 kWth) | A/A–R. | Multi-Split |

| A/A–N.R. | Mono-Split (Prated > 7 kWth) | A/W–R. | Hydronic HP (Prated < 17 kWth) |

| A/A–N.R. | Roof Top and Package | A/A–N.R. | VRF (Prated < 16 kWth) |

| A/W–R. | A/W (18 > Prated > 50 kWth) | A/A–N.R. | VRF (Prated > 16 kWth) |

| A/W–N.R. | A/W (Prated > 50 kWth) | A/W–R. | Hybrid Systems (Gas boiler + HP) |

| W/W–R. | W/W (GS-W/W-HPs) (Prated < 17 kWth) | ||

| Climatic Conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Distribution | Cold | Average | Warm |

| Stock (A) | 10.6% | 50.7% | 38.7% |

| Stock (B) | 12.8% | 48.5% | 38.8% |

| Type of Equipment | Average Lifetime [Years] |

|---|---|

| Room air conditioner | 12 |

| Mono-split, multi-split, VRF | 15 |

| Packaged, roof top | 18 |

| Precision air conditioning | 22 |

| Only cooling chiller | 25 |

| HP chiller | 20 |

| Hybrid machines | 25 |

| Type | Scope | Technology | Prated,eff [kWth] | Eres [GWh] | HP Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIR–AIR | R. | Mono-Split | P < 7 | 2267 | 14,864,192 |

| R. | Multi-Split | n.a. | 1196 | 4,488,341 | |

| AIR–WATER | R. | A/W | P < 10 | 2152 | 325,550 |

| R. | A/W | 11 < P < 17 | 1963 | 190,591 | |

| R. | Hybrid (Gas boiler + Electric HP) | n.a. | 1727 | 238,288 | |

| R. | A/W | 18 < P < 50 | 1526 | 56,546 | |

| WATER–WATER | R. | W/W (ground source included) | P < 17 | 84 | 5599 |

| R. | W/W (ground source included) | 18 < P < 50 | 162 | 3452 | |

| AIR–AIR | N.R. | Mono-Split | P > 7 | 5675 | 563,784 |

| N.R. | VRF | P < 19 | 1207 | 93,835 | |

| N.R. | VRF | 20 < P < 30 | 2211 | 96,436 | |

| N.R. | VRF | P > 30 | 4021 | 101,847 | |

| N.R. | Roof Top and Package | P < 29 | 39 | 1731 | |

| N.R. | Roof Top and Package | 30 < P < 72 | 228 | 4723 | |

| N.R. | Roof Top and Package | 73 < P < 120 | 317 | 3689 | |

| N.R. | Roof Top and Package | P > 120 | 1083 | 6492 | |

| AIR–WATER | N.R. | A/W | 51 < P < 100 | 1415 | 21,124 |

| N.R. | A/W | 101 < P < 200 | 1459 | 10,887 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 201 < P < 350 | 1074 | 4308 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 351 < P < 500 | 647 | 1670 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 501 < P < 700 | 440 | 819 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 701 < P < 900 | 138 | 185 | |

| N.R. | A/W | 901 < P < 1200 | 71 | 78 | |

| WATER–WATER | N.R. | W/W | 51 < P < 100 | 141 | 1425 |

| N.R. | W/W | 101 < P < 200 | 228 | 1162 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 201 < P < 350 | 212 | 587 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 351 < P < 500 | 103 | 189 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 501 < P < 700 | 67 | 86 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 701 < P < 900 | 36 | 35 | |

| N.R. | W/W | 901 < P < 1200 | 23 | 17 | |

| Total [GWh] | 31,911 | - | |||

| Total [ktoe] | 2744 | - | |||

| Total (units) | - | 21,087,668 | |||

| Scenario 2030 | Million [HPs/Year] | Total Number [Million Units] | Prated [GWth] | Prated,adj [GWth] | Eres [ktoe] (*) | Eres PNIEC [ktoe] (**) | Estimated Missing HP Units to Achieve the PNIEC Goal [Million Units] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A—2022 | 2.5 | 31.81 | 165.60 | 69.82 | 5029 | 4723 | - |

| B—2021 | 2.2 | 29.76 | 150.51 | 58.53 | 4168 | 3.96 | |

| C—2020 | 1.6 | 25.72 | 137.07 | 49.85 | 3505 | 8.94 | |

| D—2020 *** | 1.3 | 23.78 | 137.07 | 66.04 | 4859 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murano, G.; Caffari, F.; Calabrese, N.; Dall’Ombra, M. Meeting 2030 Targets: Heat Pump Installation Scenarios in Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135938

Murano G, Caffari F, Calabrese N, Dall’Ombra M. Meeting 2030 Targets: Heat Pump Installation Scenarios in Italy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135938

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurano, Giovanni, Francesca Caffari, Nicolandrea Calabrese, and Marco Dall’Ombra. 2025. "Meeting 2030 Targets: Heat Pump Installation Scenarios in Italy" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135938

APA StyleMurano, G., Caffari, F., Calabrese, N., & Dall’Ombra, M. (2025). Meeting 2030 Targets: Heat Pump Installation Scenarios in Italy. Sustainability, 17(13), 5938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135938