Abstract

This study investigates how digital transformation (DT) shapes ambidextrous innovation patterns (simultaneous vs. sequential) in tourism firms. It distinguishes between simultaneous and sequential innovation patterns and examines the mediating role of strategic flexibility in these relationships. Using econometric modeling, we analyze 11-year panel data (2012–2022) from 72 Chinese listed tourism enterprises. The study finds that DT positively influences both simultaneous and sequential innovation patterns. Furthermore, strategic flexibility plays a stronger mediating role in the simultaneous innovation pattern than in the sequential one. The research contributes to the DT literature by shedding light on how tourism firms can manage the challenges associated with ambidextrous innovation patterns to enhance long-term competitiveness and sustainable development. It also enriches the ambidextrous innovation literature by providing a holistic model that captures the dynamics of both patterns, offering valuable insights for tourism firms to better balance resource allocation and integrated utilization in pursuit of sustainable innovation outcomes.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of digital technologies, especially the extreme challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, DT becomes a strategic imperative for tourism firms for their long-term survival and sustainable development [1]. As one of the key industries participating in the transformation of the digital economy, the tourism industry will pay more attention to the application of big data, the internet of things, and the application of innovative activities in the process of DT, with the aim of achieving high-quality and sustainable growth [2]. At the same time, as the digital economy grows rapidly, traditional tourism companies also seek to use DT to gain a competitive edge in a turbulent market. They aim to strengthen their market position while improving their sustainability. Especially under the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic, changes in consumer behavior have made tourism companies realize the importance of DT. Emerging digital tourism projects have poured into the market one after another, putting great pressure on traditional tourism companies. DT has become one of the effective ways for enterprises to maintain their own advantages, improve their competitiveness, and pursue sustainable development in a rapidly evolving digital environment.

The DT of tourism enterprises refers to the use of digital technologies and tools to upgrade business models, improve operations, and enhance value creation [3,4,5]. The goal is to achieve long-term competitiveness and sustainable growth. Unlike the manufacturing industry, tourism companies face unique challenges in DT due to their service-oriented nature, high customer participation, and complex tourism ecosystem members. For example, tourism companies must address how to improve customer loyalty and satisfaction in the digital era [6]. At the same time, they face the challenge of adapting to a rapidly changing market [7]. They must also ensure the sustainability of their service delivery.

Existing DT literature provides theoretical insights to address the above challenges. Scholars such as Kindzule believe that tourism companies can improve customer loyalty and satisfaction by introducing digital technology to analyze the massive data generated by customers during product use [6]. Chen Linlin and others believe that DT enables tourism companies to understand customer needs from a deeper level and meet their different personalized pursuits, thereby enhancing customer loyalty [8]. However, the existing literature mainly focuses on the analysis of antecedents of the DT of tourism enterprises, for example, the impact of tourism enterprise digital technology, digital resources, and enterprise dynamic capabilities on DT [9,10]. Some of the literature analyzes the impact of DT on corporate performance. Zhang believes that the positive role of DT in expanding corporate market scope, changing service development and marketing processes, promotes corporate performance growth. Bi Jinling and Dong Shuyue believe that the extent to which tourism companies continue to improve their DT is directly proportional to corporate performance [11,12]. However, limited attention has been paid to the impact of DT on the innovation strategies of tourism firms, particularly regarding how such transformation contributes to sustainable innovation capacity.

There are some research gaps that need to be filled in. Firstly, there are blind spots in the innovation strategy. The mainstream literature prioritizes linking DT with general performance indicators such as customer loyalty or market expansion while neglecting its role in reconfiguring flexible innovation architectures. Scholars have systematically overlooked whether DT prioritizes synchronous innovation or sequential innovation, simplifying DT as a rigid efficiency tool rather than a framework for knowledge recombination, leading to real-world failures. Equally problematic is the oversimplification of the mediation mechanism. The homogenization of strategic flexibility into a single ‘dynamic capability’ masks the randomness of its pattern. The key deficiency lies in the academic failure to recognize the binary division of time structure, wherein sequential innovation necessitates temporal flexibility, whereas simultaneous innovation fundamentally depends on structural flexibility. The most crucial thing is that the sustainability link is still fragmented. Research isolates short-term DT returns from vertical innovation ecosystems. This shortsightedness overlooks the core tension of the tourism industry, which is balancing technological efficiency and experiential authenticity. Sustainable innovation requires combining digital capabilities with the human nature of the tourism industry, and ignoring this symbiotic relationship will exacerbate the vulnerability of market disruptions.

Innovation asymmetry propagates resource misallocation, driving miscalibrated investments in digital infrastructure that fail to align with firms’ specific innovation patterns. Mediation opacity obscures causal pathways, explaining why ostensibly similar DT initiatives yield divergent innovation outcomes across tourism enterprises. Sustainability fragmentation fosters technological solutionism, inviting superficial digital fixes that prioritize symptomatic relief over systemic innovation resilience.

In order to address these gaps, this study focuses on the research question of how does DT influence ambidextrous innovation patterns (simultaneous vs. sequential) of tourism enterprises. In view of this, the contributions of this article are mainly in the following three points: First, it innovatively proposes a dual innovation pattern (simultaneous vs. sequential) of tourism product and marketing innovation, enriching the research on the consequences of the DT of tourism enterprises and providing a new framework for achieving sustainable innovation. Second, the panel data is used to empirically test the impact mechanism of the DT of tourism enterprises on ambidextrous innovation, which makes up for the lack of existing data on the DT of tourism enterprises at the micro level and offers empirical support for sustainable development practices. Third, this article analyzes the mediating role of strategic flexibility in the relationship between DT and ambidextrous innovation in tourism enterprises. It also expands the scope of DT research in the context of sustainable growth.

Following this introduction, the theoretical framework and hypotheses are presented to explore the relationship among DT, ambidextrous innovation, and sustainable growth. In the third and fourth sections, methods and empirical results are explained to examine how DT influences sustainable innovation practices in listed tourism firms. Then the results are discussed with theoretical and practical implications for promoting long-term competitiveness and sustainability. In the last section, we discuss limitations and outline a future research agenda on sustainable innovation strategies in the digital era.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Ambidextrous Innovations in Tourism Industry

Ambidextrous innovation refers to two types of innovation activities in technology and marketing that need to be balanced and coordinated within an enterprise [13]. Technology innovation in tourism encompasses the creation or significant enhancement of products/services through novel technical solutions [14]. This includes digital-native experiences, data-driven service redesign [15], and platform-enabled infrastructure. Recent studies distinguish tourism technology innovation from manufacturing through its experience-centricity. Marketing innovation is defined as a new marketing approach that involves significant changes in product design/packaging, layout, promotion, or pricing to enhance experiential value [14]. The ambidextrous innovation model of tourism enterprises is divided into the simultaneous pattern and the sequential pattern. The simultaneous pattern means that tourism enterprises carry out product innovation and marketing innovation activities at the same time [13]. This model requires that tourism enterprises have sufficient internal resources to be able to cope with resource conflicts between product innovation and marketing innovation. However, this model can easily cause contradictions in the allocation of tangible resources, such as corporate liquidity and manpower allocation, and allocation contradictions in intangible resources, such as managers’ attention and decision-making capabilities [16]. The sequential pattern means that tourism companies carry out product innovation and marketing innovation in different periods. Tourism enterprises that adopt a sequential pattern can achieve innovative specialization within a certain period of time, making product or marketing knowledge accumulation more efficient [17,18]. Tourism enterprises face less pressure from resource conflicts under the sequential pattern [19]. However, the sequential pattern will cause tourism enterprises to face higher opportunity costs and risks, reducing their ability to cope with rapid changes [20].

The simultaneous pattern emphasizes balancing product and marketing innovation within the same period, while the sequential pattern focuses on focusing on a certain type of innovation in a specific period. The two types of models require enterprises to orchestrate different innovation resources to achieve them. The existing literature shows that DT is one of the important conditions for implementing ambidextrous innovation [21]. Tourism enterprises use digital technology to change their resource orchestration capabilities and provide a resource basis for enterprises to choose the simultaneous pattern or sequential pattern. AI-driven data platforms facilitate sequential specialization by rapidly isolating high-value resources for targeted innovation. This aligns with the Oslo Manual’s emphasis on digital infrastructure as a catalyst for reconfiguring innovation processes [14]. This article aims to explore the influence of DT on each ambidextrous pattern.

2.2. Digital Transformation and the Simultaneous Pattern

DT can help tourism companies improve their resource construction capabilities, accelerate the identification of internal resources and the acquisition of external resources, and improve the problem of innovation resource conflicts and competition in simultaneous patterns. At the same time, the innovative resources required by the model, such as OTA platform customer data resources and tourism market intelligence, are practical and scalable [22,23]. The model requires tourism enterprises to enrich the internal innovation resource library and fully coordinate the resource allocation between product innovation and marketing innovation [17]. DT expands the scope of enterprise resource acquisition and reduces the cost of resource search, strengthens the speed of resource collection and processing, and improves the efficiency of the distribution of digital resources among different departments of the enterprise [24]. Multiple business units can share resources [23]. It can effectively improve problems such as innovation resource conflicts faced by the simultaneous pattern.

Secondly, DT improves tourism enterprises’ resource bundling capabilities and actively integrates and manages innovative resources, which is conducive to the realization of the simultaneous pattern. At the same time, the model requires tourism enterprises to efficiently integrate product resources and marketing resources, providing sufficient space for the organization and utilization of both resources [25,26]. Digital capabilities improve the transparency of internal resources, change the original resource structure of the enterprise, and improve the active management and integration of innovative resources by tourism enterprises. Digitization strengthens the quality and management capabilities of enterprise digital resources, accelerates the integration of product and marketing resources, reduces the cost of the sharing and flowing of two types of resources, accelerates the interconnection of resources between product and marketing departments, and improves the simultaneous innovation pattern efficiency [27].

Finally, DT improves the resource matching, coordination, and value creation capabilities between different departments of tourism enterprises and further promotes the coordination role between departments. At the same time, the model requires tourism enterprises to efficiently deploy collaborative innovation activities between product R&D departments and marketing departments [28]. DT can help improve the collaboration capabilities between different functional departments, enable product and marketing departments to share resources and realize cross-functional department deployment of resources, and promote the realization of simultaneous innovation models for tourism enterprises [29].

H1.

DT positively influences the simultaneous pattern in tourism enterprises.

2.3. Digital Transformation and the Sequential Pattern

DT encourages tourism enterprises to utilize resource-building capabilities, peel off useless resources, and build enterprise-specific resource pools, which is conducive to the specificity and professional innovation of the sequential pattern. The user data of tourism enterprises is complex, making it difficult to quickly identify useful resources and peel off useless resources to form an innovative resource pool [30]. DT helps tourism companies use digital technology to quickly divest useless innovation resources with low value, efficiently build a certain innovation resource pool, and use high-value resources to carry out focused innovation, which is beneficial to give full play to the focused innovation of the sequential pattern of tourism enterprises [31,32].

Secondly, DT improves the ability of tourism enterprises to bundle resources and integrate, refine, and manage resource pools, which helps the sequential pattern realize innovation cycles in different periods. The sequential pattern can release enterprises from resource pressure, allowing enterprises to focus their innovation activities on a certain type, thereby realizing the innovation cycle of enterprises in different periods [16,17]. DT can help enterprises use digital technology to integrate old and new resources in the resource pool, especially management behaviors such as the integration and refinement of innovative resources and the recombination of irrelevant resources to form a new resource combination, which can transform the original resources [33,34]. There are continuous innovations in products or marketing and other services, thereby realizing the innovation cycle of the enterprise in different periods.

Finally, DT can promote the resource allocation capabilities of tourism enterprises, thereby promoting the development of the sequential pattern. Tourism enterprises face the current situation of highly stable organizational structures and formalized management processes [35]. However, DT can enable tourism companies to quickly respond to market demand and feedback to adjust resource allocation and invest resources in core innovative businesses that maximize corporate profits [36,37]. Enterprises can use DT to reconfigure internal and external innovation resources to adapt to the rapidly changing market environment [38]. Tourism enterprises can adjust the allocation and combination of innovation resources to focus more on product innovation or marketing innovation activities, achieve optimal allocation of innovation resources, and help tourism enterprises improve their ability to adapt to the sequential market environment.

H2.

DT positively influences the sequential pattern in tourism enterprises.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Strategic Flexibility

Strategic flexibility refers to an organizational capability to dynamically reconfigure resources and processes in response to environmental uncertainties, enabling firms to balance exploration and exploitation while avoiding competency traps [13]. Strategic flexibility is usually used as one of the important measures to stimulate enterprise innovation and change and enhance the competitive advantage of enterprises [39]. Existing research has shown that strategic flexibility encourages enterprises to use resources efficiently and plays an important role in promoting corporate innovation strategies. Strategic flexibility, as an enterprise’s ability to use resources efficiently, plays an important role in innovation [40]. It also allows enterprises to quickly understand the current market and environmental conditions, and encourages enterprises to use appropriate resources to respond quickly [41]. With the vigorous development of digital technology, how companies can use strategic flexibility and the efficient use of resources to promote optimal innovation strategies in the digital context has become a key issue that tourism companies urgently need to solve.

In terms of impact pathways, the existing research mostly focuses on one-way promotion effects, such as digital technology improving resource restructuring efficiency, but lacks exploration of reverse regulatory effects. Based on the particularity of the tourism industry, the flexibility of service scenarios emphasizes more the human–machine collaboration. The DT strategy of tourism enterprises enables enterprises to use strategic flexibility to promote resource coordination and integration capabilities in simultaneous pattern innovation. On the one hand, in the process of enterprises carrying out simultaneous pattern innovation, digital technology can accelerate the flexible use of resources among different departments of the enterprise [42]. Coordination flexibility can effectively eliminate obstacles to the transfer and utilization of resources between departments and is conducive to efficient coordination of resources when enterprises promote simultaneous pattern innovation [42]. On the other hand, the simultaneous pattern enhances the enterprise’s need to build new resource combinations and integrate resources, while enterprise DT can improve the transparency of resources among different functional departments and accelerate the integration and utilization of resources. Resource flexibility improves the efficiency of resource combination among different departments, enabling enterprises to quickly integrate and configure corresponding resources and promote simultaneous pattern innovation [43]. Simultaneous pattern innovation requires structural flexibility to maintain parallel processes.

H3.

Strategic flexibility plays a partial mediating role between DT and the simultaneous pattern.

The DT strategy of tourism enterprises strengthens the identification of external resource information and promotes the professional capabilities of enterprises to use strategic flexible development sequence model innovation. On the one hand, because enterprises adjust resources according to market changes is one of the necessary prerequisites for successful innovation, and digital technology has enriched the ways for enterprises to obtain external resource information, encouraging tourism enterprises to use high coordination flexibility to provide a rapid response to the market [44]. The opportunity of demand clarifies which type of innovation enterprises can achieve more competitive advantages by first conducting, thereby encouraging enterprises to carry out focused innovation in the sequential pattern [45,46]. On the other hand, because enterprises may continue to generate redundant and worthless resources after acquiring a large number of resources, this affects enterprises’ ability to achieve sequential pattern-focused innovation [13]. Enterprises identify resources by building digital platforms, lay a professional resource foundation for innovative activities, and form a unique innovation resource pool for enterprises [47]. At the same time, resource flexibility is used to accurately match resources within the available range, which is conducive to the specificity and professional innovation of sequential pattern innovation [48]. Sequential pattern innovation relies on time flexibility to achieve stage transitions.

H4.

Strategic flexibility plays a partial mediating role between DT and the sequential pattern.

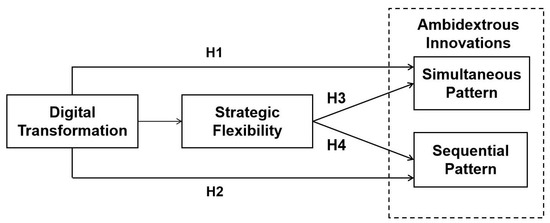

According to the theoretical analysis and hypotheses, this paper proposes the following conceptual model, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

To empirically test the hypotheses, we use the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) to construct the samples of the public listed Chinese tourism companies of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges over the 2012–2022 period. The selection of research samples follows the industry classification of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, selecting cultural, sports and entertainment industries, and accommodation and catering industries, as well as water conservancy, environmental, and public facility management industries, as research samples. Due to the fact that the industry classification of the China Securities Regulatory Commission is based on the proportion of main business income, a company will only be classified into the corresponding industry when the income of a certain type of business is greater than or equal to 50% of the total income. In addition to the three main industries mentioned above, there are also companies engaged in the tourism business in the fields of “information transmission, software and information technology services”, and “leasing and commercial services”. To avoid missing any samples, the authors conducted screening based on their business operations. After the outliers and missing values are eliminated, our final sample consists of 72 tourism firms during a 11-year period between 2012 and 2022. A total of 792 data from 72 listed tourism companies from 2012 to 2022 were obtained as the basis for analysis. The directory of the tourism enterprises is presented in Appendix A.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Simultaneous Pattern and Sequential Pattern

The study incorporates two main dependent variables: simultaneous pattern and sequential pattern. By definition, the simultaneous pattern represents the simultaneous effect of product innovation and marketing innovation in the same period [46]. The sequential pattern represents the sequential rotation of product innovation and marketing innovation in different periods, focusing on product innovation in one period first, then marketing innovation in the next period, and vice versa.

Following the ambidexterity literature, the simultaneous pattern was measured as the product term of the percentage of technological innovation and the percentage of marketing innovation in the same year t [45]. And we chose year as the time unit t to implement the operation of the simultaneous pattern. The simultaneous pattern of firms can be expressed by the product of the percentage of technological innovation in year t and the percentage of marketing innovation in year t. This measure is optimal if the firm achieves a high balance of technological innovation and marketing innovation during the same period [1]. This paper chooses the year as the time unit t to implement the simultaneous pattern, because the tourism firms will carry out strategic planning for innovation management every year, so as to determine the resource allocation to support innovation.

Regarding the choice of sequential pattern, according to the literature research on ambidextrous theory, this paper chooses a two-year window period to obtain the time cycle, and the sequential pattern of the tourism firms use t years of product (marketing) innovation [13,45]. It is represented by the product of the marketing (product) innovation percentage and the marketing (product) innovation percentage in t − 1, so as to capture the two order situations in which tourism firms first introduce product innovation and then introduce marketing innovation, or first introduce marketing innovation and then introduces product innovation. The two-year time frame was the shortest time to capture sequential patterns, which is also consistent with using a two-year time frame to study the sequential ambidextrous literature.

3.2.2. Digital Transformation

This analysis is based on obtaining the keywords related to DT in annual reports in batches through the Python 3.11 program, based on the text information of the annual reports disclosed by listed tourism companies [49]. We use content analysis in annual reports to measure DT. The content analysis can be used to analyze corporate annual reports in objective and systematic quantitative description [50]. The company’s annual financial report is the primary source of information about the company’s operations for the year; the content analysis on a company’s annual financial report is often used to quantitatively study the tourism firm’s business operation [51,52]. In this study, to improve the accuracy in analyzing annual reports, we used the contextual and keyword count methods [53]. Thus, the characterization of tourism firms’ DT is based on the frequency of digitalization, by sorting out and analyzing a large number of the annual reports of tourism listed companies for preliminary selected keywords that are highly relevant to the DT of tourism firms.

The Delphi technique is a method that obtains judgments and assessments from a group of experts about a particular topic [54]. The main features of Delphi technology are the passage of experts by virtue of a series of rounds of self-administered questionnaires, the anonymous reply of experts, and the aggregation and feedback of responses [55]. After repeated inquiries and modifications, researchers can form the consistent points as the final result [56]. In this study, the process began with a review and analysis of annual reports from tourism listed companies to identify a corpus of keywords relevant to tourism enterprises’ DT. These keywords formed the basis for constructing the first-round Delphi questionnaire. The initially identified digitalization-related keywords were then submitted to three experts/scholars specializing in tourism DT for a 3-round Delphi interview. Following interviews with the experts, their opinions were evaluated for consistency to determine the key factors influencing tourism enterprises’ DT. After three rounds of sum up and feedback, 117 keywords highly related to the description of DT were finally determined. These keywords were categorized into five domains: overall digitalization, digital R&D, digital production, digital operation, and digital marketing, as detailed in Appendix A.

3.2.3. Strategic Flexibility

Strategic flexibility (SF) was measured as financial leverage in annual reports. Through the literature review, it is found that the currently recognized methods for measuring strategic flexibility are questionnaire surveys and calculations based on corporate financial data [57]. Therefore, this paper draws on the research of Kurt and measures strategic flexibility with corporate financial leverage, that is, financial leverage is equal to the total corporate liabilities divided by the total assets [58].

3.2.4. Control Variables

We included firm-level variables to control factors that are commonly known to impact tourism innovation. We controlled enterprise advertising costs (EA), business sales (BS), business revenue (BR), and the number of enterprise technicians (ET) [59]. Table 1 summarizes the measurements for all variables. The measurements for all variables come from the annual report of the enterprise. Descriptive statistics for each variable in our dataset are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables measurement.

3.3. Model Specification

To verify the previous hypothesis, this article draws inspiration from Wen Zhonglin et al. [60]. The mediation effect test model is set as follows:

In the formula, SiP represents a homogeneous pattern; SeP represents a sequential pattern; SF represents strategic flexibility; DT represents digital transformation; i and t, respectively, represent the company and year; k represents the number of control variables; and εi,t are random terms. In models (1) and (2), α1 is the coefficient that this study focuses on, representing the impact of enterprise DT on both homogeneous and sequential patterns. In models (4) and (5), γ1 and γ2 are the coefficients that this study focuses on, representing the impact channels of enterprise DT on both homogeneous patterns and sequential patterns, and testing the mediating effect of the relationship between the two. Considering the lag effect of enterprise DT on both homogeneous patterns and sequential patterns, this paper treats all independent variables as lagged by one period.

3.4. Test

To ensure the robustness and validity of the empirical findings, this study employs the following methodological approaches.

To quantify the mediating effect of strategic flexibility in the relationship between DT and the dual innovation patterns (simultaneous vs. sequential), the Sobel–Goodman test is applied. This method statistically verifies the significance of the indirect effect (i.e., the path DT → strategic flexibility → dual innovation).

To mitigate potential measurement errors in core variables, this study implements two complementary robustness strategies. The first strategy substitutes software asset investment (DT2) for the original DT metric to re-estimate baseline regressions. The second strategy applies logarithmic transformation to the digital transformation data, specifically using *log(DT + 1)*, to reassess model stability. We consider results robust only if the statistical significance and directional consistency of key effects—particularly, DT’s impact on the dual innovation patterns—remain unchanged from baseline estimates following these methodological adjustments.

In order to address potential endogeneity issues caused by reverse causality, such as the possibility of mature dual innovation models driving DT rather than the opposite, this study adopts the instrumental variable (IV) method, using industry-level annual average digital transformation (DTA) as a tool. The basic principle of this choice is that DTA is related to DT at the company level (ensuring relevance) while maintaining exogeneity to the innovation achievements of individual companies—because the trends of the entire industry are unlikely to be directly influenced by specific innovation models of the company (satisfying exogeneity). The causal relationship is formally tested through two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression.

4. Data Analysis

Since our dataset has a panel structure, we conducted several tests to address the panel data analysis issues. First, we checked multicollinearity problems among the coefficients of interest. We found variance inflated factors (VIFs) for all the estimates, ranging from 1.06 to 1.73, with the highest VIF on business revenue and lowest VIF on enterprise technicians. Since all VIFs are lower than the threshold value of 10, multicollinearity was not a concern. Second, we use the fixed effect model and the random effect model to perform regression analysis on the above models, and use the Hausman test regression model to select the fixed effect model and the random effect model. The p value of the Hausman test is <0.05, so the null hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, we believe that the empirical results of the fixed effect model are more accurate and reasonable.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The descriptive statistics and correlation analysis for the dependent variable, independent variables, and control variables are reported in Table 2. From the results of describing statistics, it can be seen that the DT of different tourism firms is quite different. The standard deviations of the simultaneous pattern and sequential pattern are 2.989 and 0.081, respectively, indicating that there are obvious differences among tourism enterprises that adopt simultaneous pattern innovation, while the differences between different enterprises that adopt sequential pattern innovation are smaller. The standard deviation of enterprise DT is 3.864, which shows that DT varies greatly among different enterprises. Some tourism enterprises have achieved great results in DT, while others have not yet been reflected. In addition, the correlation analysis results show that the correlation coefficients between DT and the simultaneous pattern and sequential pattern are significantly positive. This preliminary alignment with H1–H2 justifies further causal testing.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results.

4.2. The Effects of Digital Transformation on the Simultaneous and Sequential Patterns

This article uses stepwise regression analysis, and the empirical results are shown in Table 3. Model 0 shows the baseline results with the addition of control variables; Model 1 analyzes the main effect; and Model 2 represents the analysis results after introducing the mediating effect of strategic flexibility. The results from Model 0 to Model 2 in Table 3 show that the impacts of DT on both the simultaneous pattern and the sequential pattern are significantly positive. Specifically, Model 1 shows that DT has a positive impact on both the simultaneous innovation mode and the sequential innovation mode (simultaneous pattern: β = 0.062, p < 0.05; sequential pattern: β = 0.068, p < 0.01). A one-unit increase in DT elevates simultaneous innovation by 6.2% and sequential innovation by 6.8%, supporting H1–H2.

Table 3.

The effects of DT on simultaneous and sequential patterns.

4.3. Mediating Effects

The preliminary results of the mediating effect are shown as Model 2 in Table 3.

This paper further quantifies the magnitude of the mediating path’s effect on the dual model transmission by conducting a Sobel–Goodman test. Table 4 shows that in the process of DT affecting the dual model, strategic flexibility plays a mediating role of 19.5% on the simultaneous pattern and 36.9% on the sequential pattern. Flexibility’s mediating role is 17.4% stronger for sequential innovation. Therefore, it can be considered that under the influence of DT, strategic flexibility plays a larger mediating role on the sequential pattern. This aligns with Model 2’s larger coefficient magnitude, indicating staged innovation demands’ greater strategic adaptation to leverage DT benefits. Therefor H3 is supported. H4 is supported.

Table 4.

Sobel–Goodman mediating effect test results.

4.4. Robustness Test

This research adopts a fixed effect model in the benchmark regression to avoid the problem of missing variables in the model to a certain extent, but the core explanatory variables may still have measurement errors. Therefore, this article uses software asset investment as a substitute variable for DT, represented by DT2. The results show that DT has a significant promoting effect on both the simultaneous pattern and the sequential pattern, and is still significant after adding mediating variables, which is consistent with the baseline regression results.

Furthermore, this paper uses the logarithm of the DT data +1 to test the robustness of the baseline regression. The results are shown in Appendix B. After changing the measurement method of DT, the promoting effect of DT on the simultaneous pattern and sequential pattern of enterprises still exists, and the promoting effect is still significant after adding mediating variables. Therefore, the findings are robust.

4.5. Endogeneity Test

Although the above regression takes into account the problems of missing variables and measurement errors to ensure the robustness of the benchmark regression in this paper, there may still be endogeneity problems. There may be a two-way causal relationship between DT and the dual innovation model, which means that tourism enterprises with more mature dual innovation models may be more willing to apply digital technology and actively participate in DT. Therefore, this paper adopts the instrumental variable method to alleviate the above endogeneity problem. The annual average value (DTA) of digital transformation in the industry is used as the instrumental variable, and the two-stage least squares method is used for regression estimation. On the one hand, this variable is related to the degree of DT of the enterprise; on the other hand, this variable has an exogenous property that is not affected by the DT of the enterprise, which meets the relevance and exogeneity prerequisites of the instrumental variable.

The regression results are shown in Table 5. The first-stage regression results show that the estimated coefficients of the instrumental variable DTA on the explanatory variable DT are all significantly positive at the 1% level. In the second-stage regression results, the estimated coefficients of the core explanatory variables are significant at the 10% level. The research shows that after considering endogenous effects, the conclusion that DT can significantly promote the ambidextrous innovation model still holds.

Table 5.

Endogeneity test.

5. Discussion

Based on unique panel data, this study investigates the relationship between DT and ambidextrous innovation patterns (i.e., simultaneous and sequential patterns) of tourism firms in China. Then, we examine the mediating role of strategic flexibility on the relationship between DT and the two innovation patterns. Our findings reveal that strategic flexibility plays a distinctive partial mediating role in this relationship, accounting for 19.5% of the effect in simultaneous innovation and 36.9% in sequential innovation. A higher level of strategic flexibility would strengthen the effect of DT on the simultaneous pattern. Our study offers some important implications for both theory and practice, particularly for promoting sustainable innovation and long-term development in the tourism industry.

5.1. Theoretical Implication

This study offers implications to the DT literature by specifying the role of DT in supporting tourist firms to handle the conflicting and complicated issues of the ambidextrous patterns of production innovation and marketing innovation. Such outcome analysis of DT in the tourist sector extends the prior DT literature that mostly focuses on the firm performance [61,62,63,64,65]. Instead, we distinguish different effects of DT on two ambidextrous innovation patterns. DT enhances simultaneous innovation by enabling real-time knowledge integration across product development and marketing channels, thereby overcoming internal coordination costs that traditionally constrained parallel innovation activities [57,64]. For instance, in the case of Dali’s homestay operators, digital platforms allow simultaneous content creation for marketing while redesigning service experiences—tasks previously hampered by operational silos. Conversely, sequential innovation benefits from digital tools that accelerate iterative experimentation cycles. Tourism firms adopting sequential patterns leverage data analytics for rapid prototyping of products before scaling marketing efforts, reducing time lags between innovation phases. This bifurcated influence clarifies why aggregated measures of innovation in prior studies yielded inconsistent results. It extends the research of tourist firms’ DT by shedding new light on the enabling role of DT, which boosts tourist firms’ capability to choose the strategy of ambidextrous patterns of innovation and pursue sustainable innovation outcomes [65].

Second, based on unique panel data of Chinese public tourist firms, we identify different effects of DT on both patterns. Specifically, we contribute to ambidextrous innovation literature by investigating the simultaneous pattern and sequential pattern in a holistic model that cannot be detected by cross-sectional data. The estimation results suggest that DT has different effects on simultaneous and sequential patterns. Simultaneous innovation relies more on structural flexibility—achieved via interoperable systems that sustain parallel workflows without reallocation delays. This explains why strategic flexibility mediates weakly in simultaneous contexts: once digital systems establish cross-functional integration, ongoing flexibility becomes less critical for maintaining parallelism. It implies the advantage of the simultaneous pattern—when maximizing the knowledge integration, the complementary of product and marketing innovation is enhanced by DT, which might cancel out the negative influence brought by its downside of inducing high internal conflicts, thereby supporting more sustainable innovation practices within tourism firms [57,58,64].

On the other hand, tourist firms are also equipped with high strategic flexibility and better control of market risk like COVID-19 by DT when they engage in the sequential pattern [66,67]. Sequential innovation inherently requires higher temporal flexibility to reconfigure resources between stages. DT facilitates this through cloud-based resource pools that allow rapid pivoting. The advantages of the sequential pattern are also enhanced by DT, which helps compensate for its drawbacks and supports more adaptive and sustainable innovation practices.

Finally, this paper clarifies the partial mediating role of strategic flexibility between DT and dual innovation models. This conclusion expands the research of Matalamäki and Joensuu-Salo on digitalization and strategic flexibility, adds the impact of dual innovation models, and makes certain contributions to the relevant literature on strategic flexibility and DT [68]. We contextualize DT’s boundary conditions within tourism—an industry neglected in the mainstream literature. Unlike manufacturing sectors, where digitalization automates standardized processes [62], tourism innovation thrives on experience co-creation. Our results show digital tools’ greatest value lies in curating hybrid physical–digital experiences. This necessitates capabilities beyond technological adoption: firms must preserve the human-centric service essence while deploying digital interfaces. When “digital-first” approaches erode interpersonal engagement—as observed in some robot-staffed hotels—innovation outcomes diminish despite technological sophistication. This industry-specific nuance challenges universalist DT frameworks and demands tailored models for service innovation. This study reveals the black box of DT acting on simultaneous and sequential innovation models through strategic flexibility and further expands the research on strategic flexibility and dual innovation strategies in the context of sustainable growth.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Our findings can provide several implications for managers regarding how to leverage DT to effectively manage the ambidextrous innovations of product and marketing innovation. First, as tourism firms strive to foster ambidextrous innovations during this period of epidemic recovery, managers need to understand the critical role of DT in effectively managing this process for long-term competitiveness and sustainable development. For firms pursuing simultaneous innovation, we recommend investing in integrated data platforms that unify customer insights across touchpoints. Sequential innovators, conversely, should deploy modular technologies allowing swift resource reconfiguration. For example, during seasonal demand shifts, Liaoning’s tourism operators use cloud-based staffing solutions to rapidly reallocate personnel from experiential design to promotion campaigns. This data-driven approach enables managers to make informed decisions, tailor their product offerings to meet customer needs, and develop effective marketing strategies that contribute to sustainable innovation outcomes.

Furthermore, managers need to foster a culture of agility and collaboration within their teams. DT enables seamless communication and knowledge sharing across departments, facilitating the integration of product and marketing innovation. Managers should encourage cross-functional collaboration, breaking down silos and promoting information exchange. This collaborative environment allows for a holistic approach to innovation, where product development and marketing initiatives align, supporting both customer satisfaction and the long-term sustainability of innovation practices.

Another crucial aspect is the need for reducing risks in tourism digitalization. To comprehensively address core digitalization risks in tourism enterprises, managers should implement three integrated strategies that collectively enhance operational resilience. The foundational strategy augments human service delivery through assistive technology integration to preserve experiential quality. Concurrently, organizations must deploy role-specific upskilling programs reinforced by certification incentives to overcome organizational resistance. Finally, enterprises should adopt blockchain-based consent systems that enable granular data control mechanisms to mitigate privacy vulnerabilities. These measures collectively convert technological risks into sustainable competitive advantages by prioritizing human–machine synergy over substitution.

Under the influence of DT, tourism enterprises need to adjust strategic flexibility to effectively configure internal resources and capabilities to achieve sustainable value creation and capture. In particular, tourism enterprises will face the challenge of reorganizing and utilizing resources after implementing DT. Strategic flexibility can help firms coordinate and allocate resources efficiently to ensure the execution of innovation strategies. Through the application of digital technologies, strategic flexibility also enhances internal communication and collaboration, enabling firms to respond quickly to external changes and maintain resilience in a dynamic environment.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

This study establishes that DT distinctively empowers tourism firms’ ambidextrous innovation through simultaneous and sequential pathways—with strategic flexibility acting as a critical yet partial mediator, whose influence varies significantly by pattern. By contextualizing these relationships within China’s dynamic tourism sector and grounding insights in empirical cases, we resolve theoretical ambiguities while offering actionable frameworks for practice. Crucially, managers must recognize that digitalization’s value lies not in technological substitution but in its ability to amplify human ingenuity—whether by accelerating iteration cycles or enabling parallel innovation streams. As emerging technologies like AI and the metaverse reshape competitive landscapes, the fusion of computational power and service authenticity will define the next frontier of tourism innovation. Those who master this symbiosis will not only survive industry upheavals but lead its sustainable evolution.

There are several limitations to this study that would provide directions for future research. First, this study employed a textual coding approach to measure the level of DT of tourism firms, using disclosed texts from listed Chinese tourist firms. It did not utilize quantitative metrics such as digital investment, digital patents, digital product revenue, etc. for direct measurement. Future studies can include these quantitative indicators to provide clearer empirical evidence. This can help better capture the extent of DT and its effect on sustainable innovation.

Second, this study selected the tourism sector as the research context, which is a unique industrial context that involves complex and fragmented value chains, with numerous stakeholders, ranging from tour operators, hoteliers, and travel agencies to local service providers [69,70]. Future research can be extended to other knowledge-intensive service industries such as financial, information, and telecommunication, where product and marketing innovation is more prevalent. This would help to generalize our findings and explore their implications for sustainable growth in broader service contexts.

Third, the econometric regression model excludes the influence of internal variables such as intellectual property and organizational learning, which may also affect the dual innovation model. Future research may consider using survey-based methods to study the relationship between DT and dual innovation models in more detail. This would enrich the understanding of innovation management and its sustainable development trajectory over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., S.P. and Y.O.; methodology, S.C. and Y.O.; software, S.C. and Y.O.; validation, S.C. and Y.O.; formal analysis, S.P. and Y.O.; investigation, S.C., S.P. and Y.O.; resources, S.P. and O.B.; data curation, S.C. and Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and Y.O.; writing—review and editing, S.C. and O.B.; visualization, S.C., S.P. and Y.O.; supervision, O.B.; project administration, O.B.; funding acquisition, O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation, grant number 21BGL058, and the Zhejiang Soft Science Foundation, grant number 2021C25033. The APC was funded by Ou Bai.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The panel data of Chinese tourism companies used in this study were sourced from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). Relevant data can be accessed at the following link: (https://data.csmar.com/, accessed on 5 July 2023). Other data used in this study are part of an ongoing research project and cannot be publicly accessed. Requests to obtain these datasets should be directed to the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the funding sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The information of the tourism enterprises analyzed in the article is presented in the following table.

Table A1.

The directory of tourism enterprises.

Table A1.

The directory of tourism enterprises.

| NUM | Enterprise | Location | NUM | Enterprise | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Huangshan Tourism Development Co., Ltd. | Huangshan, China | 37 | Huatian Hotel Group Co., Ltd. | Changsha, China |

| 2 | Shanghai Yuyuan Tourist Mart (Group) Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 38 | Nanjing Textiles Import & Export Co., Ltd. | Nanjing, China |

| 3 | Jiangsu Tianmu Lake Tourism Co., Ltd. | Liyang, China | 39 | Nanning Department Store Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 4 | Anhui Jiuhua Mountain Tourism Development Co., Ltd. | Chizhou, China | 40 | Shanghai New World Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 5 | Daqian Ecological Environment Group Co., Ltd. | Nanjing, China | 41 | Beijing Urban-Rural Commerce (Group) Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 6 | Jinling Hotel Corporation Limited | Nanjing, China | 42 | Lanzhou Minbai (Group) Co., Ltd. | Lanzhou, China |

| 7 | Shanghai Yimin Commerce Group Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 43 | China Tourism Group China Duty Free Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 8 | Shanghai Shimao Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 44 | Shanghai Lujiazui Financial Trade Zone Development Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 9 | Hangzhou Jiebai Group Co., Ltd. | Hangzhou, China | 45 | Shanghai Xinhuangpu Real Estate Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 10 | Greenland Holding Group Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 46 | Shanghai Industrial Development Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 11 | Zhejiang Xiangyuan Culture Co., Ltd. | Hangzhou, China | 47 | Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town Co., Ltd. (OCT) | Shanghai, China |

| 12 | Xi’an Qujiang Culture and Tourism Co., Ltd. | Xi’an, China | 48 | Shanghai Shimao Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 13 | Zhangjiajie Tourism Group Co., Ltd. | Zhangjiajie, China | 49 | Shenzhen Zhongzhou Investment Holding Co., Ltd. | Shenzhen, China |

| 14 | Xi’an Tourism Co., Ltd. | Xi’an, China | 50 | China International Trade Center Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 15 | Hainan Dadonghai Tourism Center Co., Ltd. | Sanya, China | 51 | Oriental Pearl New Media Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 16 | Emei Mountain Tourism Co., Ltd. | Leshan, China | 52 | Zhejiang Daily Digital Culture Group Co., Ltd. | Hangzhou, China |

| 17 | Guilin Tourism Co., Ltd. | Guilin, China | 53 | Hunan Dianguang Media Co., Ltd. | Changsha, China |

| 18 | Lijiang Yulong Tourism Co., Ltd. | Lijiang, China | 54 | Shanghai Film Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 19 | Zhongxin Tourism Group Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China | 55 | Zhejiang Culture Film Industry Group Co., Ltd. | Hangzhou, China |

| 20 | Lingnan Ecological Culture and Tourism Co., Ltd. | Dongguan, China | 56 | Guangzhou Jinyi Film and Media Co., Ltd. | Guangzhou, China |

| 21 | Tibet Tourism Co., Ltd. | Lhasa, China | 57 | Hengdian Film Co., Ltd. | Jinhua, China |

| 22 | Xinhualian Culture and Tourism Development Co., Ltd. | Lingshui, China | 58 | Songcheng Performing Arts Development Co., Ltd. | Hangzhou, China |

| 23 | Yunnan Tourism Co., Ltd. | Kunming, China | 59 | Cultural Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. | Shenyang, China |

| 24 | Changbaishan Tourism Co., Ltd. | Baishan, China | 60 | BTG Hotels (Group) Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 25 | China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited | Shanghai, China | 61 | Haobai Holding Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 26 | Shandong Airlines Co., Ltd. | Ji’nan, China | 62 | Shanghai Qiangsheng Holding Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

| 27 | China Express Airlines Co., Ltd. | Guiyang, China | 63 | Ningbo United Group Co., Ltd. | Ningbo, China |

| 28 | China Southern Airlines Company Limited | Guangzhou, China | 64 | CYTS Tours Holding Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 29 | Hainan Airlines Holding Co., Ltd. | Haikou, China | 65 | Guangzhou Lingnan Group Holdings Co., Ltd. | Guangzhou, China |

| 30 | Spring Airlines Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 66 | HNA CTS Travel Group Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 31 | Air China Limited | Beijing, China | 67 | Hubei Three Gorges Tourism Group Co., Ltd. | Yichang, China |

| 32 | Juneyao Airlines Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 68 | Xi’an Catering Co., Ltd. | Xi’an, China |

| 33 | Hainan Strait Shipping Co., Ltd. | Haikou, China | 69 | Hunan Investment Group Co., Ltd. | Changsha, China |

| 34 | Jiangxi Changyun Co., Ltd. | Nanchang, China | 70 | Beijing Jingxi Culture and Tourism Co., Ltd. | Beijing, China |

| 35 | Xiamen Yuanxiang International Airport Co., Ltd. | Xiamen, China | 71 | Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport Co., Ltd. | Guangzhou, China |

| 36 | Shanghai Jinjiang International Hotel Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China | 72 | Shanghai International Airport Co., Ltd. | Shanghai, China |

Table A2.

DT characteristic words.

Table A2.

DT characteristic words.

| Domains | Characteristic Words |

|---|---|

| overall digitalization | Internet, Internet plus, Internet of Things digitalization and intelligent technology, intelligent information platform, intelligent transformation, intelligent upgrade, cloud computing, cloud platform, cloud industry, cloud data, blockchain intelligent platform, intelligent data middle platform, intelligent upgrade, digital transformation, digital information, digitalization and intelligence, digitalization and smartization, asset digitalization platform, industrial digitalization platform, digitalization upgrade, integration platform, platform networking, big data analysis and judgment platform |

| digital R&D | digital research and development, intelligent R&D, wise R&D, artificial intelligence industry university research cooperation, digital research and development, intelligent research and development, wise research and development, R&D integration, digital design, clustered R&D, R&D informatization, iterative R&D, global R&D platform, digital innovation, intelligent innovation, and wise innovation |

| digital production | intelligent manufacturing, smart manufacturing, intelligent large manufacturing, intelligent production, smart manufacturing, intelligent monitoring, intelligent surveillance, intelligent freight, intelligent storage, intelligent warehousing, intelligent operation, intelligent assignment, intelligent scheduling, intelligent detection, intelligent automation, intelligent manufacturing, intelligent factory, intelligent chemical plant, intelligent construction site, intelligent factory, intelligent workshop, digital driven inventory, digital procurement, digital procurement, energy workshop, digital workshop, digital chemical plant, digital manufacturing, digital chemical site, industrial intelligence, production line intelligence, intelligent production line intelligent control products, intelligent maintenance monitoring, industrial Internet, intelligent processing, intelligent identification, smart identification, intelligent logistics, intelligent warehouse management |

| digital operation | intelligent control, intelligent security, intelligent judgment, intelligent operation, intelligent operation, intelligent management, smartization management, intelligent office, intelligent statistics, intelligent data scheduling, intelligent operation and maintenance, intelligent data analysis, intelligent comprehensive management information platform, intelligent information acquisition, intelligent information extraction, intelligent business operation and control, intelligent enterprise governance, intelligent middle platform, intelligent operation and maintenance, intelligent information interconnection, intelligent risk control, wisdom management, smart management, intelligent application, intelligent operation, intelligent control, smart business management, intelligent decision support, intelligent control, digital control, digital integration, digital operation, digital management, management digitization, digital operation, big data operation and maintenance, big data application, intelligent application, intelligent execution, intelligent analysis and recording |

| digital marketing | marketing intelligence, intelligent marketing, intelligent sale, intelligent services, intelligentization services, smart services, smart marketing, digital marketing, marketing digitization, retail digitization, digital precision marketing, big data marketing, digital services, intelligent customer service, service providing big data support, intelligent service methods, smart stores, smart business services, smart supply Chain, digital consumer experience, digital media, omnichannel digitization, content + social + products, interactive integration of online and offline platforms, online and offline integration |

Appendix B

The relevant tables for the 4.5 robustness test have been added as follows.

Table A3.

Robustness test 1.

Table A3.

Robustness test 1.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Pattern | Simultaneous Pattern | Sequential Pattern | Sequential Pattern | |

| Digital Transformation 2 | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** |

| (3.04) | (2.37) | (3.25) | (2.64) | |

| Strategic Flexibility | 0.047 *** | 0.034 *** | ||

| (4.03) | (4.27) | |||

| Enterprise Advertisement | 0.006 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.001 *** |

| (3.75) | (3.69) | (3.81) | (5.71) | |

| Business Sales | 0.026 *** | −0.091 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.025 *** |

| (6.91) | (−9.98) | (8.42) | (8.14) | |

| Business Revenue | −0.014 *** | −0.010 ** | −0.011 ** | −0.012 ** |

| (−2.82) | (−2.78) | (−3.55) | (−3.45) | |

| Enterprise Technicians | 0.001 ** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** |

| (3.27) | (3.62) | (3.81) | (5.14) | |

| Constant | −0.207 *** | −0.232 *** | −0.166 *** | −0.184 *** |

| (−7.58) | (−7.47) | (−6.77) | (−7.66) | |

| Observations | 792 | 792 | 792 | 792 |

| Number of Years | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| R2 | 0.191 | 0.203 | 0.204 | 0.241 |

| Adjust R2 | 0.185 | 0.196 | 0.197 | 0.229 |

| △Adjust R2 | 0.011 | 0.032 | ||

| Comparison Model | Model 1 | Model 1 | ||

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F | 40.57 | 45.20 | 28.22 | 36.34 |

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05; standard errors in parentheses.

Table A4.

Robustness test 2.

Table A4.

Robustness test 2.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous Pattern | Simultaneous Pattern | Sequential Pattern | Sequential Pattern | |

| Digital Transformation +1 | 0.001 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** |

| (2.37) | (2.54) | (3.19) | (2.85) | |

| Strategic Flexibility | 0.017 ** | 0.029 *** | ||

| (2.66) | (4.99) | |||

| Enterprise Advertisement | 0.002 *** | 0.001 ** | 0.005 *** | 0.001 ** |

| (3.42) | (2.05) | (3.69) | (2.78) | |

| Business Sales | 0.011 * | 0.003 ** | 0.025 *** | 0.023 *** |

| (3.13) | (2.85) | (8.47) | (7.50) | |

| Business Revenue | −0.001 ** | −0.008 ** | −0.010 ** | −0.011 ** |

| (−3.34) | (−2.37) | (−3.72) | (−3.56) | |

| Enterprise Technicians | 0.001 ** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 * |

| (3.27) | (6.62) | (3.82) | (0.75) | |

| Constant | −0.257 *** | −0.233 *** | −0.189 *** | −0.184 *** |

| (−7.32) | (−8.98) | (−11.14) | (−7.66) | |

| Observations | 792 | 792 | 792 | 792 |

| Number of Years | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| R2 | 0.158 | 0.164 | 0.206 | 0.217 |

| Adjust R2 | 0.151 | 0.155 | 0.195 | 0.213 |

| △Adjust R2 | 0.004 | 0.018 | ||

| Comparison Model | Model 1 | Model 1 | ||

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F | 47.52 | 36.79 | 160.7 | 109.9 |

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1; standard errors in parentheses.

References

- Kraus, S.; Schiavone, F.; Pluzhnikova, A.; Invernizzi, A.C. Digital transformation in healthcare: Analyzing the current state-of-research. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, C.; Ahmad, A.; Valeri, M.; Jaharadak, A.A. Technology acceptance antecedents in digital transformation in hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Phi, G.; Mahadevan, R.; Meehan, E.; Popescu, E.S. Digitalisation in Tourism: In-Depth Analysis of Challenges and Opportunities. Low Value Procedure GRO-SME-17-C-091-A for Executive Agency for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (EASME) Virtual Tourism Observatory. Aalborg University, Copenhagen, 2018. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/296441087/REPORT_TourismDigitalisation_131118_REV_KB_EM_4_.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Busulwa, R.; Pickering, M.; Mao, I. Digital transformation and hospitality management competencies: Toward an integrative framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slimane, S.; Coeurderoy, R.; Mhenni, H. Digital transformation of small and medium enterprises: A systematic literature review and an integrative framework. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2022, 52, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindzule-Millere, I.; Zeverte-Rivza, S. Digital transformation in tourism: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Scientific Conference. “Economic Science for Rural Development 2022”, Jelgava, Latvia, 11–13 May 2022; pp. 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.M. Opportunities and challenges of digital transformation in Vietnam’s tourism industry. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2022, 6, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Li, Y. High-quality development of digital technology enabled tourism: Theoretical mechanism and path exploration. Reform 2022, 2, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, K.; Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Z. Research on the development path of digital transformation of tourism industry. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2020, 15, 191–193+198. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Feng, X.; Ma, R.F.; Hao, C.; Wu, Y. Nonlinear effects of digital economy development on tourism total factor productivity. Tourism Tribune. 2023, 38, 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Analysis of the digital transformation development path for travel enterprises. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1370–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.; Pappas, N. (Eds.) Emerging Transformations in Tourism and Hospitality, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.K.; Tang, T.Y.; Wu, F. The ambidextrous patterns for managing technological and marketing innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 92, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Oslo Manual (The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities); OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H.; Tan, G.; Stantic, B. A fine-tuned tourism-specific generative AI concept. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 104, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, P. The Philosophy of Presence and Absence: A Study on the Antecedent Configuration and Effect of the Dual Innovation of the Champion Enterprise of Specialized Innovation under the Digital Background. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 27, 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfiluk, E. Innovativeness of tourism enterprises: Example of Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddini, K.; Hussain, M.; Gamage, T.C.; Papastathopoulos, A. Effects of resource orchestration, strategic information exchange capabilities, and digital orientation on innovation and performance of hotel supply chains. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 117, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, K.; Yu, M.; Ruan, Y. Digital transformation and resource allocation efficiency of enterprises. Sci. Res. Manag. 2023, 44, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Sun, R. Impact of Digital Transformation on Ambidextrous Innovation Synergy. Enterp. Econ. 2025, 44, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yin, T. Resource bundling: How does enterprise digital transformation affect enterprise ESG development? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Gilbert, B.A.; Barney, J.B.; Ketchen, D.J.; Wright, M. Resource orchestration to create competitive advantage: Breadth, depth, and life cycle effects. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1390–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, T. The process, difficulties and the way forward of digital transformation for SMEs. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 45, 96–107+2. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Guo, S. Digitalization promotes enterprises to decrease financialization: Evidence from asset structure. Bus. Manag. J. 2023, 45, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P.; Hodgkinson, I.R.; Elliott, K.; Hughes, M. Strategy, operations, and profitability: The role of resource orchestration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 1125–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Huang, M. Digital level and enterprise value: An empirical study from the perspective of resource orchestration. Modern Econ. Res. 2022, 4, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Qian, Y. Value creation and evolution in digital transformation of traditional manufacturing enterprises: A longitudinal case study based on resource orchestration. Bus. Manag. J. 2022, 44, 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Yu, C.; Yuan, C. Bidirectional resource acquisition, resource orchestration and digital transformation of creative enterprises—An empirical analysis based on SEM and fsQCA. Beijing Cult. Creat. 2022, 12, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnes, C.M.; Chirico, F.; Hitt, M.A.; Huh, D.W.; Pisano, V. Resource orchestration for innovation: Structuring and bundling resources in growth-and maturity-stage firms. Long Range Plann. 2017, 50, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Research on the Relationship Between Technology Orientation, Resource Orchestration and Business Model Innovation. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Li, W. Enterprise business model innovation paths in the context of digitalization—An empirical study from the perspective of resource orchestration. Green Sci. Technol. 2023, 25, 247–252+258. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ge, Y.; Llu, X. TMT cognition, faultline and innovation performance: The moderating effects of strategic flexibility. Sci. Sci. Manag. 2016, 37, 112–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yana, Z.; Gao, S.; Zena, N. Effect of strategic flexibility on exploratory innovation and exploitative innovation: The moderating effect of environmental uncertainty. Sci. Res. Manag. 2016, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wided, R. IT capabilities, strategic flexibility and organizational resilience in SMEs post-COVID-19: A mediating and moderating role of big data analytics capabilities. Global J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2023, 24, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z. Allocation in manufacturing enterprises: Research on the impact of the development of digital economy on the efficiency of resource. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2022, 39, 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, C.; Yu, C. The “double-edged sword” role of management innovation implementation on the growth of SMEs. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2018, 36, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Ye, J. Effect of environmental orientation on firms’ environmental innovation practices—The moderation of strategic flexibility. Hunan Inst. Eng. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Agostini, L.; Nosella, A.; Sarala, R.; Nkeng, C. Emerging trends around strategic flexibility: A systematic review supported by bibliometric techniques. Manag. Decis. 2023, 62, 46–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Savitskie, K.; Mahto, R.V.; Kumar, S.; Khanin, D. Strategic flexibility in small firms. J. Strateg. Mark. 2023, 31, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khristianto, W.; Suharyono, S.; Pangestuti, E.; Mawardi, M.K. The effects of market sensing capability and information technology competency on innovation and competitive advantage. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Lei, J.; Jiao, J.; Tao, Q.; Xin, B. How does strategic flexibility affect bricolage: The moderating role of environmental turbulence. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraatz, M.S.; Zajac, E.J. How organizational resources affect strategic change and performance in turbulent environments: Theory and evidence. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 632–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Enterprise digital transformation and capital market performance: Empirical evidence from stock liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Gong, Y. The effects of structure hole on firm’s dual innovation from the perspective of double-layer embedders. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2022, 39, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Lee, S.J.; Hu, C. Digitalization improves enterprise performance: New evidence by text analysis. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231175871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Du, H.; Li, X.; Cao, J. Enterprise digitalization, business strategy and subsidy allocation: Evidence of the signaling effect. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 190, 122472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Goh, P.; Pheng Lim, K. Disclosing intellectual capital in company annual reports: Evidence from Malaysia. J. Intellect. Capital 2004, 5, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C.; Zajac, E.J. The symbolic management of strategic change: Sense giving via framing and decoupling. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1173–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, S.; Witte, L.D.; Hawley, M. Exploring the potential of emerging technologies to meet the care and support needs of older people: A Delphi survey. Geriatrics 2021, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tersine, R.J.; Riggs, W.E. The Delphi technique: A long-range planning tool. Bus. Horiz. 1976, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, I.R.; Grant, R.C.; Feldman, B.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ling, S.C.; Moore, A.M.; Wales, P.W. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodological criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoloni, E.; Baussola, M. Does technological innovation undertaken alone have a real pivotal role? Product and marketing innovation in manufacturing firms. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2016, 25, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, H. How do innovation culture, marketing innovation and product innovation affect the market performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? Technol. Soc. 2017, 51, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Avrin, A.P.; Wang, X. Is China’s industrial policy effective? An empirical study of the new energy vehicles industry. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Chang, L.; Hau, K.-T.; Liu, H. Test procedure and its application. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 36, 614–620. [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen, J. Management and leadership for digital transformation in tourism. In Handbook of e-Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Yu, R.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Hu, X. An empirical study on the asset-light operation and corporate performance of China’s tourism listed companies. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, H.T.; Chen, J.S. How does digital technology usage benefit firm performance? Digital transformation strategy and organisational innovation as mediators. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2021, 35, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Rentocchini, F.; Chen, J. Antecedents of strategic ambidexterity in firms’ product innovation: External knowledge and internal information sharing. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 61, 2849–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conesa, I.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Carayannis, E.G. On the path towards open innovation: Assessing the role of knowledge management capability and environmental dynamism in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Mariani, M. Exploring the influence of exploitative and explorative digital transformation on organization flexibility and competitiveness. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 13616–13626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putritamara, J.A.; Hartono, B.; Toiba, H.; Utami, H.N.; Rahman, M.S.; Masyithoh, D. Do dynamic capabilities and digital transformation improve business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic? Insights from beekeeping MSMEs in Indonesia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matalamäki, M.J.; Joensuu-Salo, S. Digitalization and strategic flexibility–a recipe for business growth. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2022, 29, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiki, S. Quality Management in Tourism and Hospitality: An Exploratory Study Among Tourism Stakeholders. Int. J. Econ. Pract. Theor. 2012, 2, 53–61. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2150570 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Presenza, A.; Cipollina, M. Analysing tourism stakeholders networks. Tourism Rev. 2010, 65, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).