1. Introduction

Environmental awareness has garnered increasing attention among scholars, policymakers, and the public worldwide. Concepts such as sustainability and sustainable development are central to academic discussions, government policies, and international organisational strategies [

1]. Consequently, many industries recognise the necessity of integrating sustainability into their business models. The construction industry, for instance, has developed well-established guidelines and frameworks for implementing sustainability practices [

2].

Similarly, this sustainability movement has notably influenced the lodging sector [

3]. A growing body of research on hotel sustainability has emerged in response to increasing consumer demand for environmentally responsible practices [

4]. Changes in consumer environmental attitudes have significantly reshaped customer preferences and expectations, with hotel sustainability practices now viewed as essential rather than optional amenities [

5,

6]. Consequently, hotel managers are increasingly leveraging sustainability as a strategic differentiation tool, helping to attract environmentally conscious customers and enhance their competitive advantage [

7].

Previous studies have demonstrated various benefits of adopting environmentally friendly practices, including cost reductions, increased resource efficiency, innovation opportunities, enhanced customer retention, and improved employee morale [

8]. Nevertheless, Menezes and Cunha [

9] identified persistent barriers, including financial constraints and managerial reluctance, that hinder investments in eco-innovation. Furthermore, hotel initiatives aimed at adopting green practices require careful management, as poorly executed sustainability strategies can be perceived by consumers as superficial or profit-driven, which may damage a hotel’s reputation rather than enhance it [

10]. Consequently, understanding precisely which sustainability practices align with customer expectations is crucial, as customer satisfaction has a direct impact on financial success.

Recent research has focused on identifying green attributes that hotel customers primarily value [

11]. Nevertheless, the perceptions and preferences of hotel employees concerning these environmentally friendly attributes remain relatively under-explored. Since hotel employees are internal customers and essential stakeholders, their attitudes can considerably influence the effective implementation of sustainable initiatives [

12]. Therefore, it is crucial to address this research gap. However, only a few researchers have focused on the role of hotel employees [

13].

Recent discussions regarding green hospitality have expanded beyond fundamental environmental compliance to encompass more sophisticated and integrated practices, such as commitments to carbon neutrality, certified eco-labelling, and strategies for sustainable food sourcing. While these practices are still emerging, they are increasingly integral to the competitive narrative in green hotel marketing and operations [

4]. The successful adoption of these practices hinges not only on their feasibility but also on their alignment with stakeholder perceptions and expectations, underscoring the ongoing necessity for multi-perspective research, such as the present study.

This study aims to address the following primary research question: How do hotel customers and hotel staff differ in their perceptions of the importance of green hotel practices, and how do these perceptions vary in relation to demographic factors, such as gender, age, education, and income? It contributes to the literature on sustainable hospitality management while providing hotel managers with practical insights on which sustainable attributes to prioritise during the design and operational phases, informed by their significance to customers and employees.

2. Literature Review

Tourism was once considered a sector with minimal impact. However, due to increasing environmental awareness, it is now widely acknowledged that tourism can have a significant negative impact on the environment [

14]. Hotels significantly impact environmental issues because of their high energy and water consumption [

15]. Consequently, hotel sustainability has become a critical concern in the hospitality industry, driven by heightened consumer awareness of the circular economy and environmental issues [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The increasing demand from consumers compels hotel operators to implement circular and sustainable practices [

14,

20,

21].

2.1. Drivers and Barriers to Hotel Greening

The projected rise in global tourism and resource consumption has made sustainability a strategic priority for hotels [

22]. Key drivers include growing consumer environmental awareness and regulatory requirements [

23], as well as cost savings, brand differentiation, and opportunities for innovation [

7,

8,

14,

24]. Furthermore, employee engagement and enhanced operational efficiency further motivate the adoption of green practices [

8]. Collectively, these factors establish a compelling business case for sustainability, although implementation continues to face challenges from financial and organisational barriers.

Sustainability is now a key factor in maintaining a competitive advantage [

25]. For example, eco-friendly initiatives may provide operational and financial benefits, such as reduced costs through energy efficiency and waste reduction [

24]. These practices promote innovation, customer loyalty, employee engagement, and overall organisational performance [

8,

14].

Despite these benefits, hotels face barriers to implementation. Challenges include limited management commitment, lack of expertise, and financial constraints [

26]. Additionally, consumers may perceive green initiatives as marketing tactics rather than genuine efforts [

17]. Some sustainability measures, such as water conservation, may reduce guest comfort, further complicating adoption [

27]. Effective communication of these initiatives is essential to avoid perceptions of greenwashing and to build consumer trust [

28,

29].

2.2. Stakeholder Perceptions of Green Practices

Customers typically favour hotels that implement environmentally sustainable practices, yet their willingness to incur additional costs for these efforts remains limited [

30]. While eco-conscious consumers often regard sustainability initiatives as standard expectations [

31], genuine commitment to eco-friendly practices enhances customer satisfaction, loyalty, and intentions to return [

32]. Although minor inconveniences associated with green initiatives are becoming more accepted, hotels must strike a balance between sustainability and guest comfort to maintain their competitive edge [

33].

The personnel in the hospitality sector play a crucial role in the effectiveness of sustainability initiatives due to their attitudes and actions [

34]. The environmental beliefs of individual employees exhibit a positive correlation with their eco-friendly practices in the workplace, thereby emphasising the critical importance of organisational culture and comprehensive training in cultivating effective green strategies [

34]. The successful implementation of sustainability programmes and improvement of overall environmental performance rely heavily on effectively engaging staff, providing environmental education, and ensuring genuine empowerment [

35]. Initiatives designed to cultivate employee pride and commitment, exemplified by Hilton’s “We Care!” programme, demonstrate the positive influence of staff participation in achieving sustainability objectives [

36].

2.3. Theoretical Framework

This study utilises stakeholder theory as its primary theoretical foundation. As articulated by Freeman [

37], organisations are required to consider the various and often conflicting interests of both internal and external stakeholders in order to make informed strategic decisions. Within the framework of green hospitality practices, hotel customers and employees constitute two pivotal stakeholder groups whose perceptions can profoundly affect the success of sustainability initiatives. When explaining differences in individual attitudes towards sustainability, particularly those influenced by demographic factors, we also draw on elements of the value–belief–norm (VBN) theory [

38]. This theory suggests that personal values affect environmental beliefs, which in turn shape norms and behaviour. Additionally, insights from the theory of planned behaviour [

39] help us understand how attitudes, perceived control, and subjective norms may influence an individual’s perception of green initiatives. Combining these theoretical perspectives provides a solid basis for hypothesising how stakeholder groups and demographics affect the perceived value of green hotel features.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Customer and Staff Perceptions

Although early research on green hospitality often viewed sustainability as a marketing advantage, more recent studies have investigated how various stakeholders perceive and respond to specific environmental initiatives. Previous work has found that hotel customers tend to value sustainability features that are tangible and visible, such as eco-labels, energy-efficient devices, and recycling schemes [

40,

41]. These features are seen as signs of environmental responsibility that align with consumer values and identity [

42].

At the same time, a growing number of studies have examined employees’ views, revealing that staff often perceive the value of sustainability in terms of enhancing operational efficiency, improving working conditions, and aligning with ethical practices [

13,

34,

43]. Still, research has shown significant differences in perceptions on various subjects, particularly regarding certain companies’ initiatives [

44]. However, most of these studies focus on customers and staff separately, using different measures or contexts.

Building on previous research, this study carries out a direct comparison between hotel customers and staff, using the same green attributes measured on a shared scale. By examining how both groups prioritise the same sustainability practices, the study provides a more detailed understanding of stakeholder alignment or divergence. It expands on earlier findings by clearly distinguishing between external stakeholder expectations, such as customer experience and environmental signalling, and internal stakeholder operational concerns, such as labour, maintenance, and efficiency. Hence, we hypothesise the following:

H1: Customers and staff perceive green initiatives differently.

3.2. Demographic Effect on Green Perception

In the existing literature, the relationship between demographic data and indicators of environmental concerns remains a subject of contention. Empirical evidence about the impact of demographics on environmental concerns is mixed and inconclusive [

45]. Despite the mixed outcome, using demographics as a predictor of green perception remains a popular tool for eco-profiling consumers, given that demographic information is relatively easy to obtain. Many demographic factors significantly influence individual perceptions, encompassing gender, age, educational attainment, and income levels [

46]. This study aims to improve the understanding of how staff and customers perceive hotels’ environmental initiatives. Additionally, it clarifies the possible influence demographic factors have on individuals’ perceptions of these initiatives.

Research on gender as a predictor of environmental concern yields mixed findings. While many studies indicate that women exhibit improved environmental awareness, the evidence is not uniform. For instance, Amosh [

47] argues that women are generally more collaborative and actively engaged in green initiatives. Similarly, Balgansuren and N. Arunotai [

48] suggest that females demonstrate higher eco-consciousness and are more supportive of environmental regulations, particularly those related to forest preservation. However, other authors contend that no significant relationship exists between gender and environmental awareness [

49], challenging the consensus. Therefore, we propose the following:

H2: Gender impacts the perception of green initiatives.

The relationship between education and environmental concern remains inconsistent across the existing body of literature. While numerous studies suggest that individuals with higher levels of education exhibit greater environmental responsibility, primarily due to their increased exposure to ecological information [

50], there is research that challenges this assumption. On the other hand, some researchers suggest that while such education increases awareness of environmental issues, it does not necessarily translate into significant behavioural changes [

50,

51]. Considering this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: The education level impacts the perception of green initiatives.

Research regarding the influence of age on the development of ecological attitudes has yielded inconclusive outcomes. Certain studies indicate that younger individuals tend to exhibit higher environmental awareness [

52]. Conversely, other researchers argue that age alone is not a consistent predictor of environmental concern or action [

53] or highlight that older individuals show a more substantial commitment to environmental issues [

54]. Given these differing results, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H4: Age impacts the perception of green initiatives.

The existing literature does not clearly establish the connection between income levels and environmental concerns. Some studies indicate a positive correlation, implying that higher-income individuals tend to show greater environmental concern [

55]. In contrast, other research suggests a negative relationship, indicating that higher income may be associated with lower levels of environmental concern [

56]. For example, Ferreira and Santana [

57] found that lower-income individuals were more likely to engage in environmentally friendly activities. Others discovered that income plays a moderating role in the relationship between pro-environmental motivation [

58]. Complicating the matter further, Diamantopoulos et al. [

59] highlighted studies indicating no significant link between income and environmental attitudes. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: The level of income impacts the perception of green initiatives.

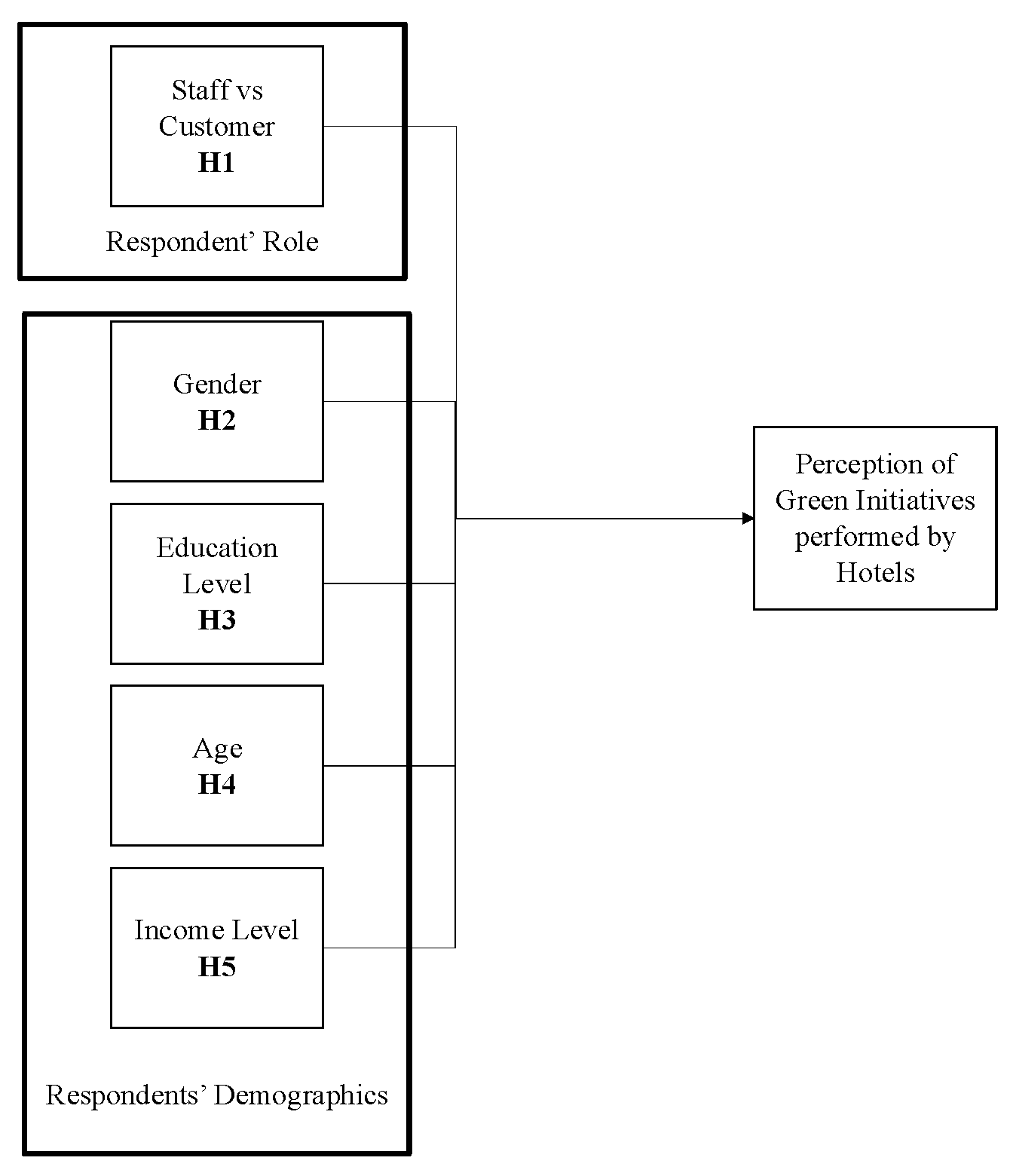

The research framework guiding this study is illustrated in

Figure 1.

4. Materials and Methods

This study used an exploratory survey to identify and examine the key characteristics of green hotels that customers and staff value. Structured questionnaires served as the principal method for data collection to accomplish this objective. The selection of questionnaires over interviews was justified by their self-administered format, which mitigated potential interviewer bias and encouraged more candid responses, particularly concerning sensitive subjects [

60].

The questionnaire included items from established research that identify essential green hotel features and reinforce their importance in evaluating customer satisfaction with sustainable practices. This study used the same questions to collect and analyse the perceptions of these features among hotel customers and staff.

Data collection centred on two specific respondent groups in the city of Porto, Portugal. A questionnaire for hotel customers was shared through social media platforms. Hotel staff participants were randomly chosen from various hotels throughout the city, representing all major star ratings. The questionnaires for staff were sent out via email and delivered in person to encourage widespread participation.

Portugal exemplifies a country where tourism has become a pillar of its economy, while also prioritising sustainable practices in the sector. Balancing tourism growth with planned investments and regulations, particularly those related to accreditation and environmental best practices, indicates a national shift towards greener hospitality. Porto, Portugal’s second-largest city and a UNESCO World Heritage-rich destination, has experienced exponential growth in the number of new hotels. Based on current licensing processes, it is expected that there will be an 84% increase in accommodation capacity, increasing the pressure on local governance to comply with sustainable urban tourism. These dynamic policy environments make Porto a highly relevant and timely case study.

4.1. Sampling and Survey Design

The study employed a non-probability purposive sampling approach. Hotel customers were recruited through social media platforms, specifically targeting individuals who had recently stayed in hotels in Portugal. For hotel staff, participants were selected from a diverse range of hotels in Porto, encompassing various star ratings and operational departments. Recruitment was conducted through two channels: (1) direct outreach to hotel managers and reception teams using publicly available contact information, and (2) in-person visits to hotel properties, where staff were invited to participate voluntarily. Staff from various departments, including housekeeping, front office, food and beverage, maintenance, and management, were included. Although the sample reflects a diverse operational cross-section, participation was voluntary and anonymous, which limits control over distribution.

The questionnaire was formulated utilising items adapted from validated instruments utilised in prior green hospitality studies [

61,

62,

63]. To ensure content validity, the instrument underwent review by three subject-matter experts in the fields of sustainable tourism and hotel operations. A pilot test involving twelve participants (six staff members and six customers) was conducted to evaluate clarity, structure, and timing. Minor adjustments were implemented based on the feedback received.

Several potential sources of bias were identified. Firstly, non-response bias may be present, particularly among hotel staff, due to the perceived sensitivity of the topic and concerns related to their employment. Despite assurances of anonymity, certain staff members may have hesitated to provide candid feedback. Secondly, social desirability bias may have influenced some respondents to rate green initiatives more favourably. To mitigate this risk, the survey was conducted with complete anonymity and emphasised the absence of correct answers. Lastly, the reliance on self-reported data and the utilisation of non-random sampling imposed limitations on the generalisability, which is acknowledged in the study’s limitations.

The questionnaire was divided into two distinct sections. At the outset, participants were asked a series of questions, each linked to one of the green hotel attributes being studied in this research. For each item, respondents were asked to rate the extent of their agreement with the specified green hotel attributes. To this end, a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 was utilised [

64]. This section of the questionnaire assessed the importance of 15 attributes associated with green hotels. A dedicated literature review was conducted to gather these attributes, which were subsequently transformed into questions, as stated in

Table 1.

The second part of the questionnaire collected demographic details from participants. For hotel customers, this included information on their gender, age, educational background, and monthly household income. In the employee survey, questions centred on gender, age, and job role within the hotel.

4.2. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 29) software was utilised to analyse the questionnaire responses. Prior research indicates that this suite is frequently and effectively employed to characterise customer satisfaction surveys. It played a crucial role in synthesising the insights of both customers and employees regarding their perceptions of the various attributes of the green hotel under evaluation [

65].

Before analysing the data collected, a thorough reliability assessment was conducted. The primary reliability indicator was internal consistency, which evaluates the coherence of the variables within a cumulative scale [

66]. The responses from hotel customers and employees were analysed using Cronbach’s alpha, resulting in an internal consistency value of 0.822. When examining the responses separately, Cronbach’s alpha for hotel customers was 0.844, while for employees, it was 0.756. An item is deemed reliable for a Cronbach’s alpha assessment if its value is above 0.7 [

66]. While factor analysis (EFA or CFA) is commonly used for scale validation, it was not applied in this case. This is because the study’s aim was not to measure latent constructs, but rather to compare perceptions across a predefined list of green attributes, each of which was treated as an independent variable. This item-level analysis aligns with the exploratory and comparative nature of the research. Future studies aiming to consolidate attributes into broader dimensions may benefit from applying factor analysis.

Research investigating how different hotel guests assess perceived eco-friendly attributes in hotels has employed the MANOVA (multivariate analysis of variance) method for analysis [

67]. The MANOVA technique facilitates the simultaneous examination of the relationships among multiple categorical independent variables and two or more dependent variables. Nevertheless, this method is only applicable if the data adhere to a normal distribution. A normality test was performed to evaluate whether the MANOVA technique could be applied in this research. This statistical test for normality relies on the skewness and kurtosis values [

66]. Kurtosis assesses the sharpness of a distribution’s peaks, with a value near zero denoting a shape that closely resembles a normal distribution. Conversely, skewness measures the degree to which a distribution deviates from symmetrical balance around the mean, where a skewness value of zero indicates a symmetric distribution. For psychometric evaluation, kurtosis and skewness should ideally remain within the ±1.0 range. SPSS’s normality test indicated that the kurtosis and skewness values exceeded the acceptable range for a normal distribution. This study also used non-parametric techniques. According to the survey results, the data did not follow a population probability distribution. As a result, the findings can be applied to data from any population with any probability distribution [

68]. This research included both green hotel features and demographic factors as dependent variables. The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed to investigate how various groups of interviewees evaluated the proposed hotel’s eco-friendly features. This investigation tested the null hypothesis, which assumed all populations were identical, against the alternative hypothesis, suggesting that certain populations displayed higher observed values than others. In practical application, the rejection of the null hypothesis utilising the Kruskal–Wallis test signified the existence of statistically significant differences in the evaluations of green hotel attributes across the various independent population groups. All tests were conducted at a 95% confidence level, rejecting the null hypothesis if the

p-value fell below 0.05. This data analysis risks incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis, referred to as a Type I error [

68]. However, pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction during data analysis with the Kruskal–Wallis test. The Bonferroni method was applied to reduce Type I errors by adjusting the analysis by the number of tests conducted.

For evaluating differences across the various levels of each independent variable, we used the Kruskal–Wallis test. The main independent variables we examined were the respondents’ age, academic qualifications, monthly household income, and their role within the hotel industry. However, it is worth noting that this test was considered unsuitable for analysing the independent variable of gender. The Kruskal–Wallis test is designed to compare three or more independent sample groups, whereas the Mann–Whitney test is used to compare two independent samples. Similar to the Kruskal–Wallis test, it employs statistical methods to ascertain whether the null hypothesis, which posits that the two populations are identical, can be rejected. This assessment highlighted the statistically significant characteristics of the respondents’ gender.

5. Results

In this study, we collected 396 valid responses from the distributed questionnaire. The findings revealed that 307 responses, or 78%, came from hotel customers, while 89 responses, making up 22%, were from hotel staff. Notably, the response rate among hotel employees was considerably lower than that of hotel customers. This discrepancy was primarily due to specific staff members’ hesitance to provide honest feedback given their hotel positions. Nonetheless, it was emphasised that the questionnaire ensured complete confidentiality and anonymity.

The analysis of respondent demographics indicated a balanced gender distribution, with females comprising 50.4% and males 49.6%. Participants were grouped into four age categories, as shown in

Table 2.

5.1. Comparison of Customer and Staff Perceptions

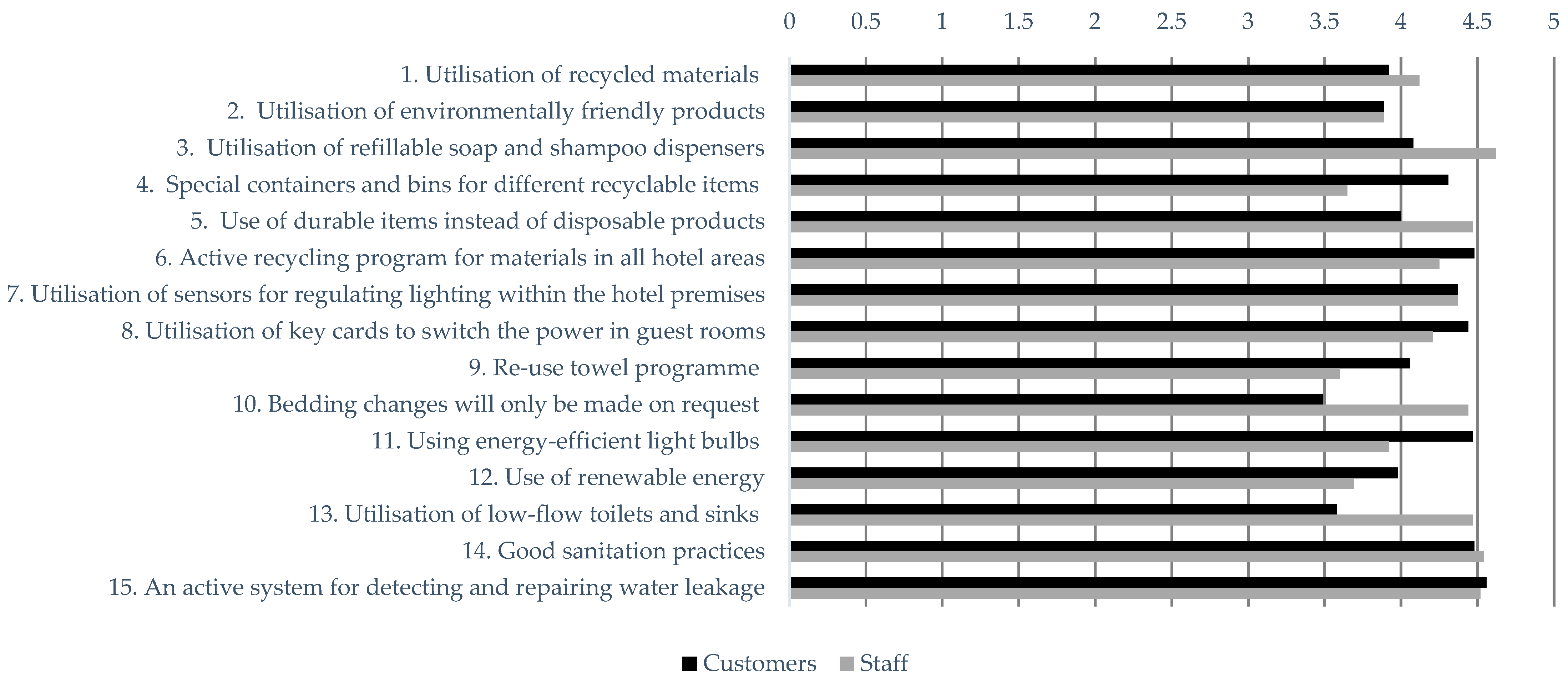

A key goal of the questionnaire was to determine how closely hotel customers and staff agreed on implementing the fifteen suggested green attributes, as outlined in

Table 1. The responses from the questionnaire served as the basis for evaluating how respondents assessed and perceived these attributes. Hotel customers and staff were asked to rate the importance of these attributes on a scale from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”), and the average level of agreement was used to rank them according to their perceived significance. Based on this Likert scale,

Table 3 shows the average outcomes and the relative significance of the various green attributes, as assessed by the two primary respondent groups. To understand the most significant differences between the points of view of hotel guests and staff, the previously mentioned findings will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

The survey results (

Figure 2) indicated that the environmentally friendly features labelled as “active system to detect and repair water leakage in toilets, sinks, and showerheads” and “good sanitation practices (such as saving water)” received high appreciation from both hotel guests and employees. This underscores the importance of water-saving solutions for hotel sustainability, as seen by both these groups. Conversely, customers had a negative view of the “use of low-flow toilets and sinks”. This reaction stemmed mainly from the belief that these water-saving initiatives would detract from the cleanliness of hotel rooms. To conclude, it can be said that, on average, none of the suggested green attributes were outright rejected by the respondents. The lowest ratings mainly indicated a degree of indifference, implying that all proposed green attributes were considered relevant in sustainable hotel practices.

To examine whether hotel customers and hotel staff perceived the 15 proposed green hotel attributes differently, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed. This statistical technique assesses any significant differences in the perceptions of green attributes held by the two groups of survey respondents. The analysis was conducted with a 95% confidence level, whereby the null hypothesis was rejected if the

p-value was less than 0.05. This criterion indicated that independent groups, customers and staff, had differing perceptions of the pertinent green attributes.

Table 3 presents the eco-friendly features with a

p-value of less than 0.05, leading to different perceptions among the two respondent groups. As a result, hypothesis H1 was supported.

The environmentally sustainable features that scored higher on the statistical test, referred to as U, were those that hotel staff viewed most positively. These features included “use of refillable soaps/shampoo dispensers”, “use of durable items instead of disposable products”, and “use of low-flow toilets and sinks”. In contrast, hotel guests prioritised features such as “special containers/bins for various recyclable items”, “towel re-use programme”, “use of energy-saving light bulbs”, and “use of renewable energy”. Although these green hotel features were classified, there were notable differences in the average ratings of hotel staff versus guests. The Mann–Whitney test revealed that only seven attributes were statistically significant. This suggests that, while overall average ratings showed slight variations, both groups assessed these green attributes similarly.

5.2. Gender

Regarding the gender effect, the survey results indicated that female respondents generally perceived the attributes described in

Figure 2 as more important. Thus, Hypothesis (H2) was validated. The factors creating the most notable differences between the two genders were the “towel re-use programme” and “change of bedsheets only upon request” (

Table 4). Nevertheless, hotel staff viewed these sustainable attributes from differing angles, with male and female members showing a stronger agreement. The only sustainable hotel feature assessed differently by gender was the “use of recycled materials”. Female staff regarded this aspect as more important than their male colleagues did.

5.3. Education Level

The questionnaire’s results also showed that most of the hotel’s eco-friendly features remained consistent regardless of customers’ education levels. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 (H3) was not supported. However, two distinct attributes showed differences. The attribute “change of bedsheets only upon request” was seen negatively by hotel guests with an EQF level of 2, while those with EQF levels 6 and 7 perceived this attribute as significant (

Table 5). Similarly, guests with higher academic qualifications considered the “towel re-use programme” significantly more important.

5.4. Age

The evaluations conducted among respondents from various age demographics of hotel customers revealed a consistent pattern without any significant disparities, resulting in insufficient evidence to support Hypothesis 4 (H4). The only characteristic that distinctly surfaced among respondents categorised by age was the “use of low-flow toilets and sinks”. Individuals “more than 41 years old” received this eco-friendly feature more positively. However, it achieved a consistent median score of 4 across all age groups. Regarding hotel staff evaluations, the “use of low-flow toilets and sinks” was the sole environmentally friendly feature that differed among various age groups. As a result, younger hotel staff regarded this green feature as more important than their older colleagues did.

5.5. Income

Analysing the monthly household income revealed that this factor did not influence how respondents valued the hotel’s eco-friendly features. The statistical analysis indicated that, at a 5% significance level, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the distribution of green hotel attributes is consistent across different income levels. In essence, there was no statistical evidence to suggest that household income affected how these attributes were evaluated. Thus, it can be concluded that respondents’ income did not influence their views on green initiatives. Therefore, H5 was not supported.

6. Discussion

This study primarily examined the differences between customers and staff as stakeholders in their valuation of green hotel practices. Additionally, it examined the impact of key demographic factors, including gender, age, education level, and regular income, on these perceptions.

6.1. Customers and Staff Role

The analysis explored hotel guests’ and staff members’ perceptions regarding the importance of specific green hotel practices. While both groups demonstrated environmental awareness and aligned on several high-priority features, such as water leak detection systems and good sanitation practices, clear differences emerged in the prioritisation of other attributes, reflecting their distinct stakeholder roles.

It is worth noting that green hotel practices can be broadly split into two categories: visible environmental measures, such as recycling bins, energy-efficient lighting, and renewable energy signage, which guests can easily spot and which affect their perceptions, and operational sustainability aspects, including low-flow fixtures, refillable dispensers, and long-lasting service items, which are less noticeable but appreciated by staff for their practical benefits and resource efficiency.

Guests favoured visible environmental measures, including recycling bins, energy-efficient lighting, and renewable energy usage. These features are easily recognisable and serve as external signals of the hotel’s commitment to sustainability. This finding aligns with previous research by Millar and Baloglu [

40] and Verma and Chandra [

62], who found that hotel guests tend to favour sustainability features that are clearly communicated and non-disruptive to their experience. Similarly, initiatives perceived to compromise comfort, such as low-flow fixtures and refillable dispensers, were rated lower by guests, consistent with concerns reported in earlier studies about hygiene and convenience.

In contrast, hotel staff valued operational sustainability aspects more strongly, such as the use of refillable amenities, durable materials, and low-flow plumbing systems. These preferences reflect an emphasis on resource efficiency and functionality, in line with findings by Zaman et al. [

13] and Rubel et al. [

34], which emphasised the role of operational staff in implementing sustainability initiatives. Employees are typically more attuned to the day-to-day implications of green practices, including workload, resource use, and operational effectiveness.

One notable divergence from earlier studies was the relatively high rating assigned to staff for low-flow fixtures. Although customers linked these features to reduced comfort, staff probably saw them from the perspective of efficiency and environmental impact, indicating a closer alignment between sustainability values and operational awareness among employees.

These results reinforce the idea that customers and staff perceive green hotel practices through fundamentally different lenses. Customers evaluate features in terms of experience and comfort, while staff emphasise efficiency and practicality. This divergence underscores the importance for hotel managers to strike a balance between these two perspectives when designing and communicating sustainability initiatives.

6.2. Demographic Effect

Table 4 highlights the green hotel features that female customers valued the most. These attributes pertained to two primary aspects of sustainability: energy conservation measures, such as using key cards to cut off power in unoccupied accommodations, and water-saving techniques, which include prolonging linen usage and incorporating systems to detect water leaks in restroom facilities. This information supports earlier findings suggesting that female customers consider the proposed green features more important than male customers [

70]. The study revealed that male customers often had differing perspectives from female customers regarding linen reuse options, showing a lesser appreciation for care strategies associated with bed sheets and towels. Although female and male guests may have different opinions about a hotel’s sustainability efforts, their staff views tended to be more consistent. This consistency may stem from their involvement in hotel operations, creating mutual respect for the promoted sustainable practices.

An analysis of respondents’ educational levels revealed that most evaluations of the hotel’s eco-friendly features were consistent across different educational backgrounds, with two significant exceptions. These exceptions corresponded to gender-related attributes: the “change of bedsheets only upon request” and the “towel re-use programme”. This indicated that individuals with higher academic qualifications were more inclined to value linen-related aspects, demonstrating a greater willingness to wait longer for towel and bedsheet replacements than those with lower educational levels.

An examination of respondents’ age groups showed a notable age difference in the perception of the attribute “use of low-flow toilets and sinks” associated with green hotels. Younger participants rated this aspect more favourably compared to their older counterparts. Furthermore, the “towel reuse programme” and the “use of durable items instead of disposable products” received high ratings from the younger demographic. No significant variations were found concerning the age demographic for the other green attributes. Typically, younger participants demonstrate a greater inclination towards the sustainable attributes of green hotels compared to older respondents [

40,

62]. This study suggests that the gap in environmental awareness among different age groups, particularly among younger and older individuals, is relatively minor. While younger generations show interest, older travellers tend to hesitate towards sustainable practices. However, the findings imply that the age-related difference in environmental awareness is less pronounced than in previous studies. Guests and hotel staff of various ages from around the world assessed the suggested eco-friendly features of hotels in a remarkably consistent way.

As previously mentioned, the analysis of survey results regarding the influence of monthly income on respondents’ perspectives about hotel sustainability features indicated that this demographic factor had no significant effect. This statement aligns with the view of Nimri et al. [

70] when analysing the factors that affect consumers’ intentions to purchase from environmentally friendly hotel accommodations. The authors found that the income of hotel customers had little effect on their assessments of green products.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Environmental issues are crucial for both consumers and service providers. The hotel industry is actively responding to these global challenges. Consequently, hotels are under greater pressure to implement eco-friendly features in response to rising customer demand. However, hoteliers need to promote the implementation of sustainable practices that focus on the most effective green features, ensuring that customer satisfaction remains intact.

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on sustainable hospitality by offering a dual-stakeholder perspective on the perceived value of green hotel practices. While previous research has largely focused on customer preferences, this study addressed a notable gap by comparing hotel customers and staff using a shared evaluative framework. This side-by-side analysis provides a more comprehensive understanding of stakeholder alignment and divergence in sustainability priorities. The findings also operationalised stakeholder theory within the hospitality context by demonstrating how stakeholder roles influence the perceived relevance of specific sustainability measures. Furthermore, the study introduced a helpful conceptual distinction between visible environmental measures and operational sustainability aspects, which clarified the mechanisms underlying perception gaps. By incorporating demographic analysis into stakeholder comparisons, this research extended existing work on environmental attitudes by demonstrating how factors such as gender and education influenced the valuation of green initiatives across different stakeholder groups. These contributions reinforce the theoretical framework for future research on inclusive and context-sensitive sustainability strategies in the hospitality sector.

7.2. Practical Contributions

This study provided valuable insights for hotel managers seeking to implement sustainable initiatives that appeal to both guests and staff. The findings suggested that hotel customers value visible environmental measures, including recycling bins, energy-efficient lighting, and the use of renewable energy. Consequently, hotels should emphasise these features in their marketing materials, room signage, and digital platforms. For example, placing clear labels near recycling points or displaying in-room cards that explain the use of renewable energy can bolster customer trust and satisfaction.

Moreover, staff emphasised the importance of operational sustainability practices, including the use of refillable amenities, durable service items, and low-flow plumbing fixtures. Hotel managers can support these preferences by involving staff in sustainability planning and training programmes. For instance, operational teams could participate in selecting refillable product systems or establishing procedures for towel reuse programmes to ensure both effectiveness and employee buy-in.

Furthermore, areas of convergence, including leak detection systems and sanitation practices, symbolise low-resistance opportunities for prompt implementation. These attributes were esteemed by both stakeholder groups and can be adopted with negligible trade-offs. The effective communication of such dual-benefit measures can foster internal alignment and enhance customer confidence.

Finally, considering the gender-based differences observed, with female guests showing a greater appreciation for energy- and linen-saving initiatives, marketing strategies could be tailored to emphasise these aspects more prominently when targeting environmentally conscious traveller segments.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study presents several limitations. First, data collection was restricted to the city of Porto, which limits the generalisability of the findings. While Porto provides a dynamic and pertinent environment due to its rapid tourism growth and evolving sustainability policies, its specific cultural and regulatory context may not accurately represent conditions in other regions or countries.

Second, we acknowledge the limited number of staff responses (n = 89), which was considerably lower than that of hotel customers. This limitation was partly due to employees’ reluctance to provide candid feedback, despite the survey’s assurances of anonymity. While the dataset still yielded statistically significant results, the underrepresentation of staff voices may restrict the depth of insight into internal stakeholder perceptions. Future studies should strive to enhance staff participation, potentially through institutional partnerships or anonymous digital platforms, to ensure broader representation.

To build on the current findings, future research should employ broader and more diverse sampling strategies, ideally encompassing multiple geographic regions and hospitality markets. Comparative studies across different cultural and regulatory contexts would help assess the transferability of the findings and reveal how stakeholder perceptions of sustainability vary globally. Additionally, expanding the analytical model to include organisational factors, such as hotel brand, ownership structure, and marketing positioning, could further enrich the understanding of how green practices are perceived and implemented within the hospitality sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.; Methodology, M.A.T.; Validation, M.G.; Data curation, I.M.; Writing—original draft, I.M.; Writing—review & editing, J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Because the study neither gathers sensitive personal data (e.g., health status, race, sexual orientation) nor involves vulnerable populations (such as minors, older adults, or patients), and it poses no psychological or emotional risk, it qualified for exemption from formal ethical review and approval.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed in this study are not publicly available because of privacy constraints, but they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Usman, M.; Khan, N.; Omri, A. Environmental policy stringency, ICT, and technological innovation for achieving sustainable development: Assessing the importance of governance and infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, M.; Elmasry, M.; Mashhour, I.M.; Amer, N. A framework for assessing sustainability of construction projects. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 13, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Moreno, S.; Aydemir-Dev, M.; Santos, C.R.; Bayram-Arlı, N. Emerging sustainability themes in the hospitality sector: A bibliometric analysis. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2025, 31, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreahi, M.; Bujdosó, Z.; Lakner, Z.; Pataki, L.; Zhu, K.; Dávid, L.D.; Kabil, M. Sustainable Tourism in the Post-COVID-19 Era: Investigating the Effect of Green Practices on Hotels Attributes and Customer Preferences in Budapest, Hungary. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.X.F.; Hsu, C.H.C.; Liu, A.X. Transforming Brand Identity to Hotel Performance: The Moderating Effect of Social Capital. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 47, 1270–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.C.; Agyeiwaah, E.; Liu, J.; Scott, N. Social justice or social stigma? Hotel customers’ perception on branded hotel used as quarantine facility. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, R.; Victoria, O.E.R.; Tegethoff, T. The role of quality in the hotel sector: The interplay between strategy, innovation and outsourcing to achieve performance. TQM J. 2025, 37, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassinis, G.I.; Soteriou, A.C. Greening the service profit chain: The impact of environmental management practices. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2009, 12, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, V.; Cunha, S. Eco-Innovation in Global Hotel Chains: Designs, Barriers, Incentives and Motivations. Braz. Bus. Rev. 2016, 13, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinot, E.; Giannelloni, J.L. Do hotels’ ‘green’ attributes contribute to customer satisfaction? J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Gursoy, D.; Dang-Van, T.; Nguyen, N. Effects of hotels’ green practices on consumer citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 118, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moğol Sever, M. Improving check-in (C/I) process: An application of the quality function deployment. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.I.; Qabool, S.; Anwar, A.; Khan, S.A. Green human resource management practices: A hierarchical model to evaluate the pro-environmental behavior of hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 1217–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Mansour, M.A.; Mohammad, A.A.A.; Fayyad, S. Understanding the Nexus between Social Commerce, Green Customer Citizenship, Eco-Friendly Behavior and Staying in Green Hotels. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.S.; Trang, H.L.T.; Kim, W. Water conservation and waste reduction management for increasing guest loyalty and green hotel practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H. Customer retention in the eco-friendly hotel sector: Examining the diverse processes of post-purchase decision-making. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahia, M.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S.; Elshaer, I.A.; Mohammad, A.A.A. Greenwashing Behavior in Hotels Industry: The Role of Green Transparency and Green Authenticity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julião, J.; Gaspar, M.; Tjahjono, B.; Rocha, S. Exploring Circular Economy in the Hospitality Industry. In Innovation, Engineering and Entrepreneurship; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julião, J.; Gaspar, M.; Alemão, C. Consumers’ perceptions of circular economy in the hotel industry: Evidence from Portugal. Int. J. Integr. Supply Manag. 2020, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julião, J.; Gaspar, M.C.; Tjahjono, B. The Social, Economic, and Environmental Dimensions of Hotel Sustainability; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P. Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaal, A.; Bakri, A.; AlKhatib, N.; Chreif, M.; Zakhem, N.B. Harvesting sustainability: Navigating green practices and barriers in Lebanon’s hospitality sector. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, T.; Wilson, C.; Månsson, J.; Hoang, V.; Lee, B. Do environmentally sustainable practices make hotels more efficient? A study of major hotels in Sri Lanka. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saepudin, P.; Putra, F.K.K. Analyzing the Application of Cleanliness, Health, Safety, and Environmental Sustainability (CHSE) Certification During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perspectives of Hotel Managers. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 29, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, A.; White, L.; Pyke, J.; McGrath, M. Barriers and drivers of environmental sustainability: Australian hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1830–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeis, G.; Legrand, W. Sustainability Challenges and Opportunities in Hospitality Marketing: A Regulatory and Consumer Perspective. In Brand Leadership im Tourismus: Mit starken Marken zum Erfolg; Gardini, M.A., Ed.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2025; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bernard, S.; Rahman, I. Greenwashing in hotels: A structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preziosi, M.; Tourais; Acampora, A.; Videira, N.; Merli, R. The role of environmental practices and communication on guest loyalty: Examining EU-Ecolabel in Portuguese hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeazzo, A.; Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Green procurement and financial performance in the tourism industry: The moderating role of tourists’ green purchasing behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Kwon, J. Green hotel brands in Malaysia: Perceived value, cost, anticipated emotion, and revisit intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1559–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Ali, F. Why should hotels go green? Insights from guests experience in green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Raab, C.; Yoo, M.; Love, C. Sustainable hotel practices and nationality: The impact on guest satisfaction and guest intention to return. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Kee, D.M.H.; Rimi, N.N. Unpacking the eco-friendly path: Exploring organizational green initiatives, green perceived organizational support and employee green behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 2049–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D. Culture and Job Satisfaction. Purdue University Global. 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12264/576 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P.; Novotna, E. International hotel chains and environmental protection: An analysis of Hilton’s we care! programme (Europe, 2006–2008). J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Human Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M.; Baloglu, S. Hotel Guests’ Preferences for Green Hotel Attributes. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 5, 1–12. Available online: http://repository.usfca.edu/hosp/5 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.-E. ‘Green’ practices as antecedents of functional value, guest satisfaction and loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dash, S.; Mishra, A. All that glitters is not green: Creating trustworthy ecofriendly services at green hotels. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J. Unlocking service excellence: The hierarchical impact of high-performance human resource practices. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 37, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; Abdullah, S.N.C.; Haron, S.N.; Hamid, M.Y. A review of green practices and initiatives from stakeholder’s perspectives towards sustainable hotel operations and performance impact. J. Facil. Manag. 2024, 22, 653–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Mika, M.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M.; Krzesiwo, K.; Pawłowska-Legwand, A. Predictors of patronage intentions towards ‘green’ hotels in an emerging tourism market. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wong, P.W.; Narayanan, E.A. The demographic impact of consumer green purchase intention toward Green Hotel Selection in China. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 20, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H. The role of gender diversity in shaping green collaborations and firm financial success. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2025, 40, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balgansuren, O.; Arunotai, N. Insights on energy, poverty, and gender nexus in urban ger district households: A case study from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Glob. Transit. 2025, 7, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumara, K.; Mane, S.; Diksha, J.; Nagaraj, O. Effect of Gender on Environmental Awareness of Post-graduate Students. Br. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 8, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Perales, I.; Valero-Gil, J.; la Hiz, D.I.L.-D.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C. Educating for the future: How higher education in environmental management affects pro-environmental behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirbiš, A. Environmental Attitudes among Youth: How Much Do the Educational Characteristics of Parents and Young People Matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 11921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, B.M.; Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Age and environmental sustainability: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 826–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, F.; Liu, Y. Pro-Environmental Behavior in an Aging World: Evidence from 31 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F.C. The Varied Influence of SES on Environmental Concern. Soc. Sci. Q. 2014, 95, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.Y. Negative income effect on perception of long-term environmental risk. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 107, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.A.; Santana, S. Low-income people and pro-environmental behavior: Beyond money issues, a literature review. J. Educ. Technol. Health 2021, 2021, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, E.; Merten, M.J. High-income Households—Damned to consume or free to engage in high-impact energy-saving behaviours? J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 82, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallowfield, L. Questionnaire design. Arch. Dis. Child. 1995, 72, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. Hotel Guest’s Perception and Choice Dynamics for Green Hotel Attribute: A Mix Method Approach. Indian. J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, H.L.T.; Lee, J.S.; Han, H. How do green attributes elicit pro-environmental behaviors in guests? The case of green hotels in Vietnam. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, I.; Design, Q. Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.; Sengar, S. Unraveling the Role of IBM SPSS: A Comprehensive Examination of Usage Patterns, Perceived Benefits, and Challenges in Research Practice. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 9523–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Hampshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Merli, R. Delighting Hotel Guests with Sustainability: Revamping Importance-Performance Analysis in the Light of the Three-Factor Theory of Customer Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop; ETF; UNESCO; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Global Inventory of Regional and National Qualifications Frameworks, UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. 2019, 2, 1–774. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/7xc0nh (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Jin, X. The determinants of consumers’ intention of purchasing green hotel accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

_Li.png)