1. Introduction

Living Labs (LLs) have gained interest as experimental, living spaces for prototyping and learning related to complex societal challenges through real-life co-creation. LLs typically involve a wide range of stakeholders including researchers, policymakers, businesses, and citizens [

1,

2]. Rooted in a vision of innovation through participation, LLs aim to develop, test, and refine ideas within situated learning contexts to support sustainable transitions [

3]. Their promise lies in the ability to engage people not just as passive recipients of innovation, but as co-designers of alternatives and co-producers of knowledge related to change.

Yet, critiques of LLs have pointed out some reasons for concerns. Many LLs operate within limited project timelines, often associated with project funding, which can restrict the continuity and depth of transformative change [

4,

5]. Additionally, studies have questioned the authenticity of participation, arguing that co-creation is frequently used but not reflected in terms of lived realities of local communities involved in LLs [

6,

7]. Furthermore, LLs often rely on metrics and evaluation models that are quite linear, leading to overlooking cultural, relational, and long-term impacts [

8,

9]. As such, studies call for research that goes beyond institutional actors to examine how LLs can scale “deep”, that is, identify and enable changes in underlying values, behaviours, and social structures [

1].

Scaling deep goes beyond expansion or influencing systemic structures per se and instead entails gaining deeper understandings of values and relationships in striving for meaningful change [

10]. Thereby, scaling deep pivots lived realities and embedded knowledge of people instead of generalising contextual specificity. Achieving deep scaling requires a more nuanced understanding of stakeholder engagement and involvement within Living Lab approaches. Yet, existing LL frameworks seldom provide concrete strategies for the meaningful inclusion of local community actors [

6,

7]. Similarly, Torma [

11], underscores through an extensive literature review how limited our knowledge remains regarding how LL projects identify and engage stakeholders, despite this being widely recognised as fundamental to the LL model’s capacity for sustainable transformation.

In this article, we will address these gaps by highlighting the role of a particular type of stakeholder, the local community champion. The concept of champions is increasingly relevant for describing local stakeholders who act as gatekeepers to community values, practices, and relationships, particularly in initiatives that seek to embed change within local contexts [

12]. The emerging literature extends the notion of champions beyond formal organisational roles to include community-rooted actors who wield influence through trust, local knowledge, and everyday engagement. While traditional accounts frame champions as institutional figures who mobilise resources and overcome resistance to innovation (e.g., [

13,

14]), contemporary research highlights their roles within cross-organisational ecosystems [

15,

16]. However, much of this work continues to focus on formal actors. In contrast, a growing strand of research emphasises informal champions—individuals embedded in local networks who act as connectors, translators, stewards, and sometimes critics [

17,

18,

19]. These community champions are particularly valued in participatory settings for their role in grounding and sustaining initiatives.

This study draws on design ethnography to investigate how community champions act as relational nodes across community domains such as knowledge and participation. Rather than focusing solely on experimental interventions, we trace how champions help embed values and practices that inspire LL activities. This attention to embeddedness is particularly relevant in communities where trust in institutional actors may be low, and where existing networks play a central role in social sustainability [

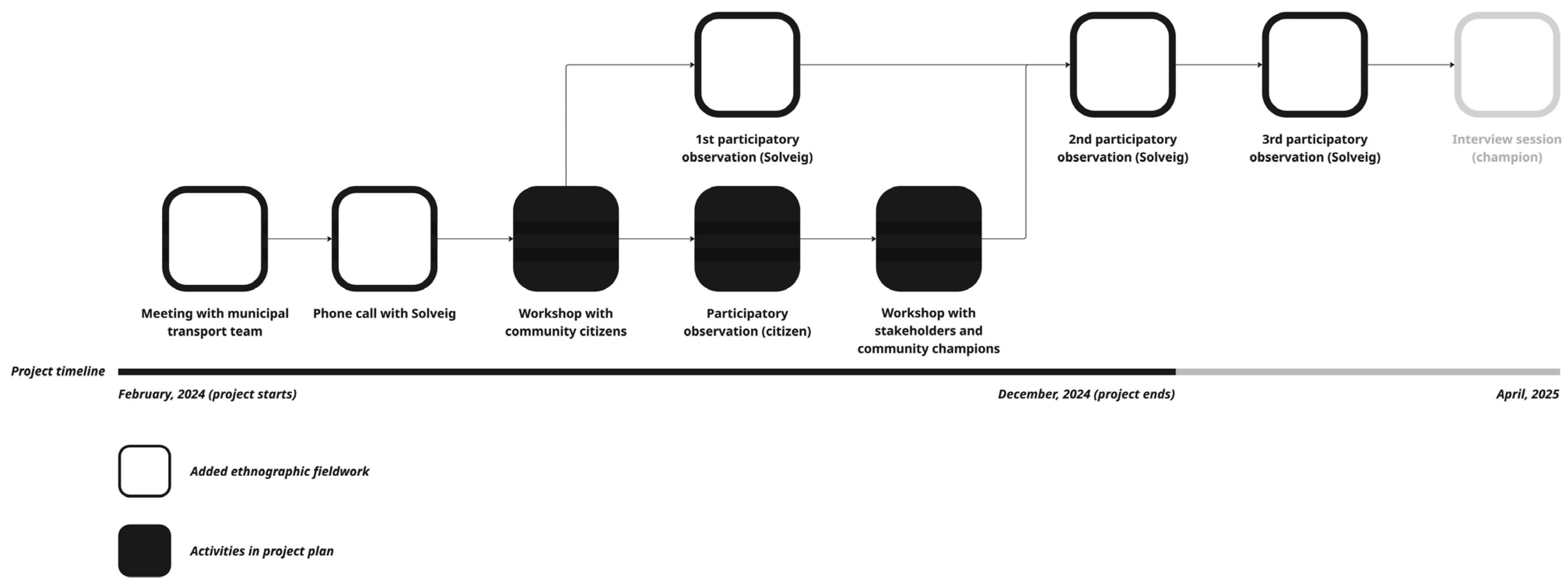

12]. We argue that this reciprocal nature of the ethnographic LL approach fosters meaningful relationships and mutual understanding, which can support ongoing change and sustainable transformation beyond the formal lifespan of the project. We present empirical examples from a design ethnographic Living Lab project on future mobility, conducted between 2024 and 2025, which illustrate how the process of reciprocal alignment between project ambitions and the perspectives of local champions unfolded in practice. Drawing on this fieldwork, we explore the following overarching question: how can Living Lab projects scale deep through sustained ethnographic engagement with local champions?

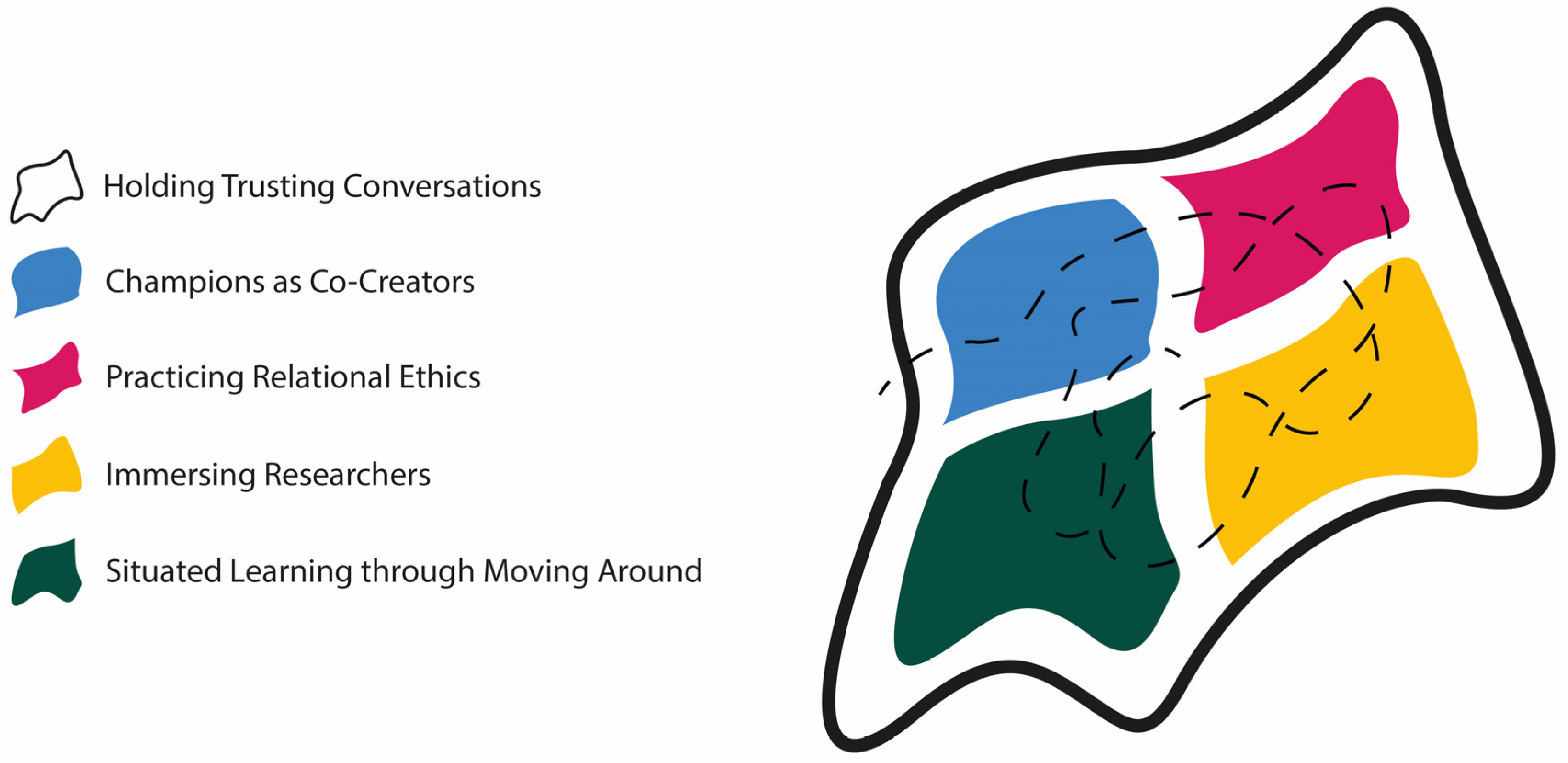

In doing so, we propose that a better understanding of community champions may also inform how to design a tailored LL approach that can potentially support long-term sustainable transformation and social impact beyond the Living Lab. Our contribution lies in the development of the concept of “scaling deep” by mapping the situated and relational dimensions of champion co-creation captured in our Deep Scaling Reciprocity Map (Figure 2). From this, we suggest how LLs can move from temporary interventions toward long-term, locally rooted change.

4. Results

The principal findings emerging from the research and the development of the Living Lab highlight five relational practices of reciprocity that evolved in collaboration with the community champion over the course of the project. Each of these practices directly engages with the research question posed in this article: how can Living Lab projects scale deep through sustained ethnographic engagement with local champions? As outlined below, the practices exemplify the processual, relational, and co-creative dimensions of deep scaling as they unfolded in practice. They are presented through a series of focused ethnographic scenes, grounded in thick descriptions [

41], that illuminate key moments from 18 months of fieldwork. Rather than aiming for comprehensive coverage, these scenes are carefully selected to represent broader patterns in our data, capturing how reciprocity evolved in situ through sustained engagement with local champions in a Living Lab context.

This mode of representation is deliberately chosen to foreground the situated, relational, and contextually embedded character of the interactions. It enables the reader to encounter lived experiences as they unfold within specific spatial and social environments, illustrating how meaning is co-produced over time.

Particular attention is paid to moments where the local champion engaged with us as researchers, highlighting the emergence of reciprocal, co-creative relationships. These scenes are not purely descriptive; they are analytically inflected accounts that illustrate what we identify as core relational practices to emphasise how writing does not simply communicate ethnographic insights, but, as a result of the activity of texts, it was also part of generating them through the ongoing analysis of interpreting observations into text [

40]. Each scene is followed by a brief interpretive commentary that draws out its significance, thus combining narrative texture with analytical insight. This approach is consistent with ethnographic traditions that seek to capture ambiguity, nuance, and the complexity of human interaction through layered and grounded storytelling [

36].

4.1. From Gatekeepers to Co-Creators

The first contact with Solveig did not follow any formal protocol or prearranged meeting, but instead took place over the phone, prompted by a list of “local, intermediate organisations” from the municipality’s transportation team. Though no names were provided, the transportation team’s willingness to engage grew as I explained the difficulty of recruiting participants from the area. They mentioned the area’s many active volunteers, directing me toward grassroots actors, or “driving spirit”, without naming anyone specific. Among the organisations listed, Solveig’s stood out, described as “one of the most active”, hinting at her role not only as a civil society actor but as a key figure with deeper access to the community.

Instead of following official routes, access came through ad hoc, relational negotiations with local gatekeepers. A quick online search led me to a phone number, and when I called, Solveig answered. Despite my preparations—notes on the project’s aims, ethical protocols, and research goals—her response was immediate. She invited me to visit the very next day, positioning herself not as a gatekeeper but as a co-actor in initiating the project. I had to decline, explaining that we were still fine-tuning the details. The contrast between her proactive approach and my institutional need for preparedness highlighted a misalignment between academic and community timelines.

When I called her again the following day, Solveig had already spread the word, speaking to others and beginning the recruitment process without waiting for formal confirmation. This was no longer a simple facilitation; Solveig had taken on the role of a community leader, invested in our project.

Initially, we approached the field with a more traditional view of champions as gatekeepers: as a one-directional power dynamic where gatekeepers were seen as facilitators and access points for us as researchers. However, through our ongoing fieldwork in the project and interactions with our local champion, a more nuanced view began to emerge. As the scene describes above, the champion was not only a mere participant or facilitator in the research process, but an active co-creator of the project and LL design. That is, shaping the direction, framing, and outcomes of the project itself.

4.2. Relational Ethics in Practice

The workshop day came. It took place on the ground floor of a rented apartment building connected to another local organisation. The room was filled with everyday signs of community life: flyers, a small kitchen area, and a bulletin board crowded with events, announcements, and reminders. This board was not just informative; it was a pulse of collective activity, reminding people that “things are happening, and you are invited.” It served as an open invitation to the community, and some glanced at it casually, while others studied it closely.

We arranged six or seven tables into small islands, hoping to encourage openness, but underestimated the social dynamics of how these spaces were used. At 16:03, Solveig was pouring coffee, laying out fika, and answering questions about everything from visa issues to upcoming events. She moved effortlessly between topics, offering care, attentiveness, and weaving connections as she went. People arrived slowly, some left, and others returned as the flow of participation was far from linear. It became clear that our time-based, structured approach was less relevant than we had anticipated. The atmosphere was in-and-out as you want, rather than punctual.

When presenting our research, we handed out GDPR-compliant forms meant to ensure informed consent. However, the legal language disrupted the workshop’s flow, leaving participants hesitant. They seemed to question, “Who are these people, really? And why do they want me to sign something so official?” A noticeable sense of distrust lingered—not directed at us personally, but at the institutional culture we brought with us. Solveig stepped in, not by explaining the legalities, but by translating the forms into familiar language, framing them within the context of the community. What could be won by committing to the session, and most importantly, signalling her own trustworthiness.

This workshop scene, intended to map mobility patterns, revealed more than we expected. It highlighted the friction between institutional taken-for-granted practices (such as research ethics protocols) and their practical applications in this particular LL setting. In this case, the forms, designed for protection, underscored the effort needed to establish trust. As participants eventually picked up pens to map their daily mobility, it became clear that the act of participation was co-created. Responses were achieved not through perfect workshop design, but through Solveig’s relational work, making it possible for people to engage. Her presence bridged the gap, showing that this was a process worth trusting. Solveig encouraged people to talk to us, despite the scepticism that sparked from the GDPR documents.

4.3. Immersing the Researchers

On September 4th, I met up with community champion Solveig to follow her along during a day in the area. This day was the first Wednesday of the month, meaning residents would meet up at a local physical spot to discuss happenings and plan for coming events, while also introducing themselves and their organisations to community members.

The physical setting was a centrally located place on the bottom floor of a rental apartment house built in the latter half of the 1900s. It contained a small stage for talks, with seats for listeners, a back-room workshop area for art and construction, a small kitchen for preparing food and drinks, and an open space organised with tables and chairs for people to gather around during this Wednesday. The walls had bulletin boards containing upcoming and outdated events, which was the second physical artefact Solveig interacted with upon her arrival after making sure registration lists were placed accessibly by the entrance.

The atmosphere could be described as informal, and time was not prioritised as Solveig felt it was more natural to use “human time” than anything else. People could come and go as they wanted, and at a quarter past the appointed time the premise was full, leading to a queue being formed outside the venue. The guests were mainly community members and community organisation members, but there were also local business owners, local politicians, and newcomers to the community, ranging from children with their parents to seniors.

After welcoming everyone by name, Solveig used the brought-in microphone and speaker to introduce the agenda for the get-together, which included a co-created speaker list that anyone who visited could write their name on to speak about their visions, organisations, or interests for one minute. The list was soon filled with intermediate organisation representatives, including the research team and our background, and local community members encouraged by Solveig and other community champions. The way Solveig designed and invited us into the community meeting highlighted the reciprocity that was quietly being negotiated. When the speaking list was run through, we ate injera cooked by an Ethiopian organisation and moved around to speak to other community leaders and members of interest. I approached two men that recently started a handball club for kids. We found common interests for future studies. I have never called them. Yet.

Rather than the formal introduction of the researcher into the community, Solveig’s approach was one of subtle co-creation. She did not just allow our presence in the space—she actively made it part of the fabric of the meeting, positioning us alongside other community actors. In this particular scene, by including us on the speaker list, she signalled not just tolerance, but a shared stake in the success of the gathering. Through this relational dynamic, Solveig created a space where our role as researchers was woven into the ongoing, organic flow of community interactions. The invitation was not only an introduction to the community, but an invitation to participate fully in the co-creative process, where mutual trust and respect were the foundation. Everyone could talk; everyone had one minute each.

4.4. Situated Learning Through Moving Around

Solveig and I took a walk from The Spot—our usual meeting point—at around 16:00 on one of those spring afternoons that slows everything down. The square was alive with market shoppers, workers drifting home, friends gathered on benches. As we walked, Solveig pointed out places where community organisations had once gathered, fizzled, or re-emerged. Near a sunken garage entrance, she paused: “Maybe here,” she said, imagining a future prototype session of a design concept. Our walk became a kind of spontaneous community visioning, co-mapping spaces of potential for coming project activities.

She carried her worn tote—“Hjärnan”, (Swedish for “the brain”) as she called it—filled with flyers that worked like memory prompts. She handed them out selectively, depending on who she expected to meet. “This one’s for [name], we’ve got a meeting tomorrow,” she said. It was not just distribution. It was care, timing, recognition. People received the flyers as something meaningful, not generic. She remembered what might interest them, and the flyers reminded her of what to tell. She had a way of making it feel natural, sometimes even generous.

We stepped into the local library, tucked behind what used to be a bank vault. I signed up for a card I would never use, just to show a kind of presence. On the wall hung “book bags” filled with curated selections for parents. They were age-specific, multilingual, and designed with care for parents who may not have the time or knowledge to select books for their kids themselves. Later, we passed a taped-up flyer on a metal door; a part-time bike repair shop, quietly combining circular economy goals with grassroots employment. It was closed, but Solveig spoke about it with quiet pride as it was envisioned to combine informal community needs with employment.

Throughout our walk, Solveig occasionally checked her phone, her WhatsApp group more specifically. It had grown from 30 to over 400 members, all women. It had begun with “a bit of cheating”, she joked, referencing an early workshop where all participants joined. She never added me to the group. “We’re trying to keep it safe,” she said. I respected that boundary.

We eventually arrived at the venue for the champion network meeting. Shoes spilled across the entryway. Inside, a coffee pot gurgled behind a glass door. The room was informal, the agenda hand-held and barely visible. We went round introducing ourselves short, grounded, not rehearsed. I was new, a PhD student from Halmstad. Others were long-time collaborators, community leaders, volunteers, city reps. No formalities, just shared purpose. We later walked to the event site to plan placements and responsibilities. It was my first time. Solveig knew everyone.

This scene demonstrates how ethnographic engagements are more than a tour or a pre-meeting. It was a form of mutual learning. Solveig shared her world; I shared our project. Through her actions, not words, she modelled co-creation, relational access, and trust-building. Reciprocity emerged not through formal agreements, but through shared steps, time spent, and a way of moving together. As we wrapped up, this session made it possible for us to speak more freely about the possibility of future collaboration where her organisation could step in not just as a “community contact” but as a committed, strategic partner.

4.5. Holding Trusting Conversations

Solveig and I set off towards The School, where she and three other community leaders were due to speak on a panel tied to a local parenting course. Just as we left The Spot, the community centre, her phone rang as someone needed the keys back. At that very moment, a young woman passed us. “Hi, Solveig!” she called. Solveig waved, phone still to her ear, and quickly asked if the woman could deliver the keys on her way. It was a smooth, offhanded relay of trust.

Moments later, Solveig turned to me with a look of mild concern. “That ring has my house keys,” she said. “If it disappears, I’m done for.” Then added, almost to herself, “Let it be worth it.” She didn’t mean it dramatically. Just a quiet, everyday kind of risk, trusting others for the sake of the wider community’s flow. “For the greater cause”, I replied. We smiled, but the exchange held a trace of the fine line between personal exposure and collective effort. Solveig coordinated care, and practiced it, even when it cost her something small but vital.

As we walked, she told me about a course she had just completed with local police and support services. It focused on the shifting methods of youth recruitment into criminal networks—less at youth centres now, more through encrypted apps. “It’s Discord, Snapchat… and this one?” she asked, showing me an unfamiliar icon. “Wickr”, I said. “It deletes messages after they’re read”. “Yes! That one”. She saw learning these new codes not just as information, but protection. A part of a growing role she played in both physical and digital guardianship of her neighbourhood. “No one dares to speak anymore”, she added later, touching on the silent fear that had crept into the community, referring to tactics used by criminal gangs in the area. Solveig mentioned she was in a Zoom meeting the other day with other community champions across Europe to discuss the issue. They had all met through a course that ended in February but continued connecting independently for mutual learning. “It’s joint”, Solveig said when I asked who was teaching whom, indicating a sense of shared leadership and knowledge sharing.

Talk shifted to legacy. Many long-time community figures were ageing out of active work. But now, twelve younger people had stepped forward. “Four even applied for funding, and got it!” she said, visibly hopeful. But the catch was clear: “They often have to give up income to do this. And they’re sharp! Strong networks. But [one of them] will probably stick to their profession.” I asked what could change that. “Money,” she said bluntly. Support wasn’t just moral—it needed to be material. After the panel, we walked back to The Spot. Solveig reflected on the growing gap between institutional metrics and community experience. “Agenda 2030, or whatever it’s called. Look at things, we’re not going to make it,” she said. “So why do they only care about CO2?”. Her frustration was with the selective urgency of policy that rarely aligned with daily, lived emergencies.

This, and similar walks and their moments, reveals how reciprocity developed not through grand gestures, but in accumulated acts of trust, and shared risk. Through Solveig’s actions, such as delegating with care, she translated institutional discourse into lived meaning and gradually wove the researchers’ presence into the community’s own rhythms. Solveig did not treat us as researchers visiting the community, but invited us into a relationship, built on trusting conversations and daily exchanges. By doing so, Solveig showed how micro-relational acts bind people together within a community.