1. Introduction

Understanding the impact of crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic on both the food system and people’s behavior is important in ensuring the resilience of public health as well as environmental sustainability. A healthy diet is characterized by a balance of essential nutrients, including a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, while limiting processed foods, added sugars, and unhealthy fats; such diets are fundamental in preventing chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and in promoting mental health, quality of life, and wellbeing [

1,

2].

A sustainable diet, on the other hand, extends beyond individual health to include environmental, economic, and social considerations. It emphasizes the consumption of foods that have a low environmental impact, are culturally acceptable, nutritious, and economically fair. This typically involves prioritizing whole plant-based foods, reducing meat consumption, and minimizing food waste, all of which contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of our diets—such diets are often both healthier and more sustainable than the average Western diet [

2], and as such are important to meeting both environmental and public health goals. During events like pandemics, economic downturns, or natural disasters, people’s food choices may shift dramatically due to altered availability of foods, economic constraints, and psychological stress. By studying these dynamics, we can better prepare for future crises and promote diets that are both healthy and sustainable, ensuring resilience in our food systems and public health.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns and quarantines were a period of high stress for individuals [

3], with lockdown measures linked to increases in general psychological distress [

4], anxiety, and depression [

5]. The pandemic and its wider societal impacts also resulted in changes to food systems with widespread labor shortages, fragmented supply chains, shop closures, and panic buying [

1,

6], leading to alterations in the availability and accessibility of food [

7]. Food insecurity intensified during the pandemic due to financial insecurity and job losses [

8]. Food insecurity in UK adults quadrupled in the first weeks of COVID-19 [

9] and particularly impacted vulnerable groups such as those on low incomes, and people with young children [

10,

11].

Due to the widespread social changes, individuals faced challenges in maintaining a healthy and sustainable diet. Indeed, eating patterns changed during the pandemic [

12]. For some, these dietary changes led to diets becoming healthier, with increases in fruit and vegetables and fish reported [

13,

14,

15] and increased overall diet quality [

16]. However, for many, the changes resulted in less healthy diets with increased consumption of snack foods, carbohydrates [

13,

14,

15,

17], and other ultra-processed foods, as well as more frequent alcohol consumption [

18], and more frequent meals [

13,

19]. Moreover, for those that experienced positive shifts in diet and activity, these were often short-lived, with later phases of the pandemic marked by increased stress, reduced physical activity, and declining diet quality [

20]. Such dietary changes may have impacted on weight status in the population [

14], with reports of increased weight [

13]. Although negative dietary changes were widespread [

17], they were most often noted in people with negative mood, and those with higher levels of depression and anxiety [

21].

Dietary changes occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic for a variety of reasons.

Some people made positive changes, such as eating more fruit and vegetables, to help protect themselves against COVID-19, with early evidence indicating that dietary choices could help to protect against the virus [

22]. Other dietary changes were the result of alterations in food access and affordability, with an increased usage of food delivery services, changes in food supply chains, and changes to employment status [

23]. Changes in diet were also driven by the fear and anxiety experienced [

24], with increases in emotional and comfort eating [

25]. Many people used food as a coping mechanism to the stresses of the pandemic [

20], leading to increases in unhealthy eating habits [

26]. Emotional eating was particularly common among younger adults and those facing prolonged social restrictions [

27].

Food insecurity was also a risk factor for negative dietary changes, with research suggesting that those who experienced food insecurity were likely to have altered their diets more considerably [

28].

The widespread negative dietary changes, such as reductions in fruit and vegetable consumption, that were seen during the COVID-19 pandemic are concerning given that such changes are both less healthy and less sustainable [

2]. It is therefore important from both a public health and environmental perspective to understand dietary changes, their causes, and mitigating factors, so that targeted interventions can be developed to better cope with future crises.

In the present study, we aimed to extend the understanding of risk and protective factors for maintaining a healthy and sustainable diet during times of crisis using the COM-B framework. The COM-B framework [

29] proposes that capability (C) (both physical and psychological), opportunity (O) (both physical and social), and motivation (M) (both reflective and automatic), need to be considered when looking to understand why certain behaviors (B), such as the dietary changes seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, occur. This framework was selected as it provides a useful lens through which to examine behavior change in response to complex, real-world contexts such as the COVID-19 pandemic. COM-B has been widely used in public health and behavioral research, including exploring individual health behavior relating to the COVID-19 crisis.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals experienced different opportunities to deal with stressors such as physical and social barriers to exercising or eating healthily, had different capabilities that resulted in physical and psychological barriers to being active or accessing healthy food, and/or had different motivations which resulted in intrinsic and automatic emotional barriers that we hypothesize led to different dietary choices and physical activities, and in turn, varying abilities to cope.

The COM-B framework does not focus extensively on emotional factors as cause of behavior but rather considers these as integrated within the model components, notably automatic motivation. Given the stressful nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, we extended the analysis to include an in-depth assessment of both stressors and drivers of resilience, which is the ability to adapt and remain functionally stable during stressful situations [

30,

31]. There are various factors that contribute to resilience. Adaptive emotion regulation may act as a protective factor against burnout during the pandemic, while maladaptive emotion regulation heightens the risk of burnout [

32]. Adaptive emotion regulation encompasses functional reactions to emotional events such as accepting them or being able to see them in a calm or positive way, whereas maladaptive strategies are often marked by (escalating) negative thoughts [

33]. However, resilience is also supported by activities that directly induce positive states such as physical activity or experiences of social connection [

34]. Previous research has also emphasized the positive effects of being in nature [

35], and it is plausible that, given the already established link between greenspace and reduced stress levels [

36], and the restrictions on movement during lockdown periods, the environment in which people lived may have played an important role in how people coped during the pandemic.

This study has two aims: first to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted dietary choices and behaviors amongst parents of children under 18 years of age in the UK with a focus on risk and protective factors, and second, to examine factors that either increased stress and lowered wellbeing or mitigated against negative impacts of the pandemic on health and wellbeing, promoting resilience. To explore these aims, we implemented online surveys at two different times in the pandemic in the same group of parents in the UK allowing us to perform longitudinal analyses across the two time points; and conducted a series of focus groups with a subset of the same parent sample. Parents were chosen as the population of interest due to the potentially great impact of changes in childcare and schooling during the pandemic and the resulting stress and upheaval [

10].

We stratified gender and socioeconomic status during recruitment to allow us to gather insights into different groups of respondents. The questions posed during the surveys and focus groups were informed by the COM-B framework [

29] such that we sought to explore capabilities (physical and psychological), opportunities (physical and social), and motivations (reflective and automatic) in relation to dietary choices, physical activities, and wellbeing, in order to gain a better understanding of what drives changes to people’s diet and wellbeing and what factors may promote resilience. The insights garnered from this study hold significance for future crisis management strategies and for individuals presently grappling with stress.

This study offers several novel contributions to the literature on dietary behavior and resilience during crises. First, to the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study to take a longitudinal mixed-methods approach, collecting data at multiple time points during the COVID-19 pandemic to examine changes in dietary behavior, coping strategies, and stress in the same group of individuals. Second, the study applies the COM-B framework to understand how capability, opportunity, and motivation influence diet and coping behaviors in a real-world crisis setting, extending its utility beyond individual-level health interventions to broader societal disruptions. Third, we developed and applied an Integrated Health and Sustainability Score, building on work by Strid et al., [

37] to evaluate individual dietary patterns based on both health and environmental criteria, offering a holistic assessment aligned with global goals for sustainable nutrition. Finally, by stratifying participants by gender and socioeconomic status, and combining survey results with in-depth focus groups, we were able to surface nuanced insights into how stress, emotional regulation, and coping mechanisms interact with food behaviors during times of elevated uncertainty. These contributions provide an evidence base for designing tailored interventions to support dietary resilience during future pandemics, economic downturns, or climate-related disruptions.

2. Materials and Methods

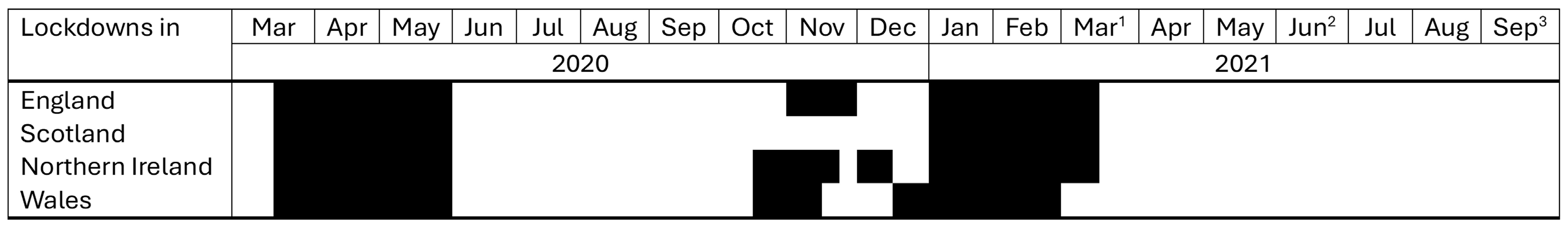

Data were collected through three instruments: two online surveys and a series of online focus groups (see

Figure 1 for a timeline of data collection). Survey 1 was conducted between the 19 and 25 March 2021, towards the end of the winter/spring COVID-19 lockdowns in the UK. During this period, travel restrictions remained in place, but students were beginning their return to schools [

38,

39,

40,

41]. A second survey was undertaken from 21 to 30 September 2021, at which point most legal limits on contact had been removed in England since July 19th of that year [

38].

This study was guided by a set of exploratory research questions rather than formal a priori hypotheses. Given the complexity and evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study was designed to examine associations and emerging patterns across dietary behavior, perceived stress, and coping strategies using both quantitative and qualitative data. The analysis was theoretically informed by the COM-B framework [

29], which structured our investigation into how capability, opportunity, and motivation influenced participants’ behaviors over time.

Survey data are reported following CHERRIES guidelines [

42]. All data collection questions were optional due to the potentially distressing nature of the questions, and the voluntary participation of those taking part. As a result, the number of responses reported varies between questions, and does not always equal the total number of respondents in each survey.

Focus groups were hosted in June 2021, 5 weeks after Survey 1. All respondents to Survey 1 were invited to take part. Those that agreed to take part were grouped based on self-reported sex and their coping/stress score derived from the online survey.

2.1. Survey 1 (March 2021)

2.1.1. Sampling Procedures

Survey 1 was advertised on Prolific, a survey recruitment platform [

43], and participants self-selected to take part. Adults who were living in the UK and had children (under 18 years) living with them during the pandemic were eligible to take part. Participants were redirected to Qualtrics, which provided information about the study and enabled participants to provide consent before taking part in the survey. The survey was self-reported and took approximately 15 min to complete. One question was presented per page. Backwards navigation was not enabled. Participants could withdraw from the survey at any point. Participants received GBP 1.88 as compensation for completing the survey, which was equivalent to GBP 7.52/hour, with the survey sample maximized within funding restrictions.

Using Prolific Academic’s demographic screening to provide a balanced sample, participants were recruited based on sex and self-reported socioeconomic groups (in Prolific participants select the ladder rung from 1 to 10 which best represents their socioeconomic status, from the best off to the worst off in society).

2.1.2. Materials

Survey 1 was developed to examine food behavior before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and to gather information regarding a range of risk and protective factors for maintaining a healthy, sustainable diet. All data collected were self-reported. The online survey was developed in Qualtrics. First, the survey asked questions about the participants’ diet to create a combined health and sustainability score, described in more detail below. Hereafter, we asked questions to understand factors that might represent risk or mitigating factors for participants’ ability to sustain or switch to a healthy and sustainable diet. These were inspired by the COM-B model, and on emotional and wellbeing-related factors highlighted in the literature. We used the U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form to measure food security [

44] to assign a food security classification to respondents of either food secure (0–1), low food security (2–4), or very low food security (5–6). We also measured aspects of reflective motivation to eat healthily. As motivation is impacted not only by the value people place on an activity but also their perception of how easy or difficult it is to perform [

45], we used two questions asking participants how motivated they felt and how difficult they found it to eat healthily since the start of the pandemic in March 2020. We also asked participants to indicate how motivated the pandemic made them to eat more healthily, more sustainably, and to be more physically active in the future. Both questions used a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 5 = very much).

A series of questions explored factors affecting diet, stress, and coping behaviors throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. To this end, we used three subscales from the COVID-19 Pandemic Mental Health Questionnaire (CoPaQ) [

46]. Specifically, we used seven items from the COVID-19-specific stressors impact subscale asking participants to rate a variety of stressors. We did not use items that might not have applied to all participants such as “being in home office”. The implemented items asked participants to rate on a 5-point Likert scale the stress or burden felt in the past 14 days by worries about their health, about not being able to get medical care, increased conflicts with people close to them, childcare, financial concerns, and uncertainties about work/study.

Reliability analyses indicated adequate reliability in both surveys (Cronbach’s αSurvey 1 = 0.858; Cronbach’s αSurvey 2 = 0.831). We also presented participants with the three items of the subscale measuring social cohesion, asking them to describe their subjective impression of it at that point in time. For instance, participants were asked whether they had the feeling that “our nation is growing closer over the past 14 days” on a 5-point Likert scale (Cronbach’s αSurvey 1 = 0.832; Cronbach’s αSurvey 2 = 0.836). To measure how participants coped by themselves and in interaction with others, we then asked them to fill out 13 items that comprised the scale measuring positive coping. This evaluated whether participants maintained a daily routine, had social contact but also privacy, and used inner strength (e.g., “I changed my attitudes about what is important to me in my life”) and one item of the interpersonal conflict scale, as before these items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (Cronbach’s αSurvey 1 = 0.702; Cronbach’s αSurvey 2 = 0.691).

We used three additional questions to measure emotional eating/drinking adapted from Burgess et al. [

47]. The questions asked participants to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always) how often they ate or drank unhealthy/unsustainable foods and drinks (sweets, fast foods, sugary drinks) to forget their problems, to cheer them up, or to be sociable (Cronbach’s αSurvey 1 = 0.694; Cronbach’s αSurvey 2 = 0.734). We then presented them with 20 tickable items that represented (mal-)adaptive emotional functioning such as “I am able to meet my emotional needs” or “I feel sad often”.

In addition, participants were asked to provide the first four digits of their postcode, to enable location-specific insights to be ascertained, and to opt-in to take part in a subsequent focus group. Finally, the survey included questions about demographic factors including age, sex, number of children, and location, as well as childcare/caring responsibilities.

All questions in the survey included a “not applicable”, “I don’t know”, or “prefer not to say” option. See

Supplementary S1 for the complete survey. The survey was piloted with a sample of 10 parents in England prior to being administered to the population sample to test the usability, comprehensibility, and technical functionality of the survey. The pilot led to minor changes in the wording of questions for clarity and to remove minor errors, but no questions were removed or substantially changed.

2.1.3. Development of an Integrated Health and Sustainability Score

Using data from Strid et al. [

37] on combined nutritional and environmental food evaluation, an Integrated Health and Sustainability Score (ISS) was developed for use alongside the survey. A detailed breakdown of the ISS components and scoring criteria, including food group classifications and point allocations, is provided in

Supplementary S2.

For each food group included in the survey’s consumption questions (fruit, vegetables, unbattered fish, whole red meat, processed red meat, crisps), an average ISS was calculated based on individual food category combined nutritional and environmental scores from Strid et al. [

37]. Vegetables (score of 1) and fruits (1.43) had the lowest ISS scores while processed (5) and whole red meat (5) had the highest, with unbattered fish (3) and crisps (4) coming in between.

The scoring system was developed to reflect public health nutrition priorities in the UK and broader sustainability goals by encouraging plant-based, minimally processed food intake. Although this scoring system does not take into account all possible variations of food products or agricultural production systems within these categories, it is aligned with literature on combined environmental and health impacts of food, where red meat has been identified as having high impacts in both categories and fruits and vegetables having low impacts in both categories [

48] and with the EAT-Lancet’s planetary diet recommendations [

2], and provides a snapshot of the health and sustainability of participant diets. This resulted in three point-in-time values and three change-over-time values, as described in

Table 1.

2.2. Focus Groups (June 2021, During Lockdown Easing)

Small focus groups, with 2 to 3 participants per group, were hosted online via MS Teams. Participants were assigned a group based on their self-reported sex and their coping/stress score from the surveys: male high stress, male low stress, female high stress, and female low stress. However, only three focus groups were conducted as the high-stress male participants who had signed up did not attend the scheduled focus group and did not respond to a request to reschedule. Group 1 included 3 females, all of whom were coded as low stress based on their coping/stress score from their surveys, Group 2 included 3 males, all of whom were coded as low stress based on their coping/stress score from their surveys, whilst group 3 included 2 females, both of whom were coded as high stress.

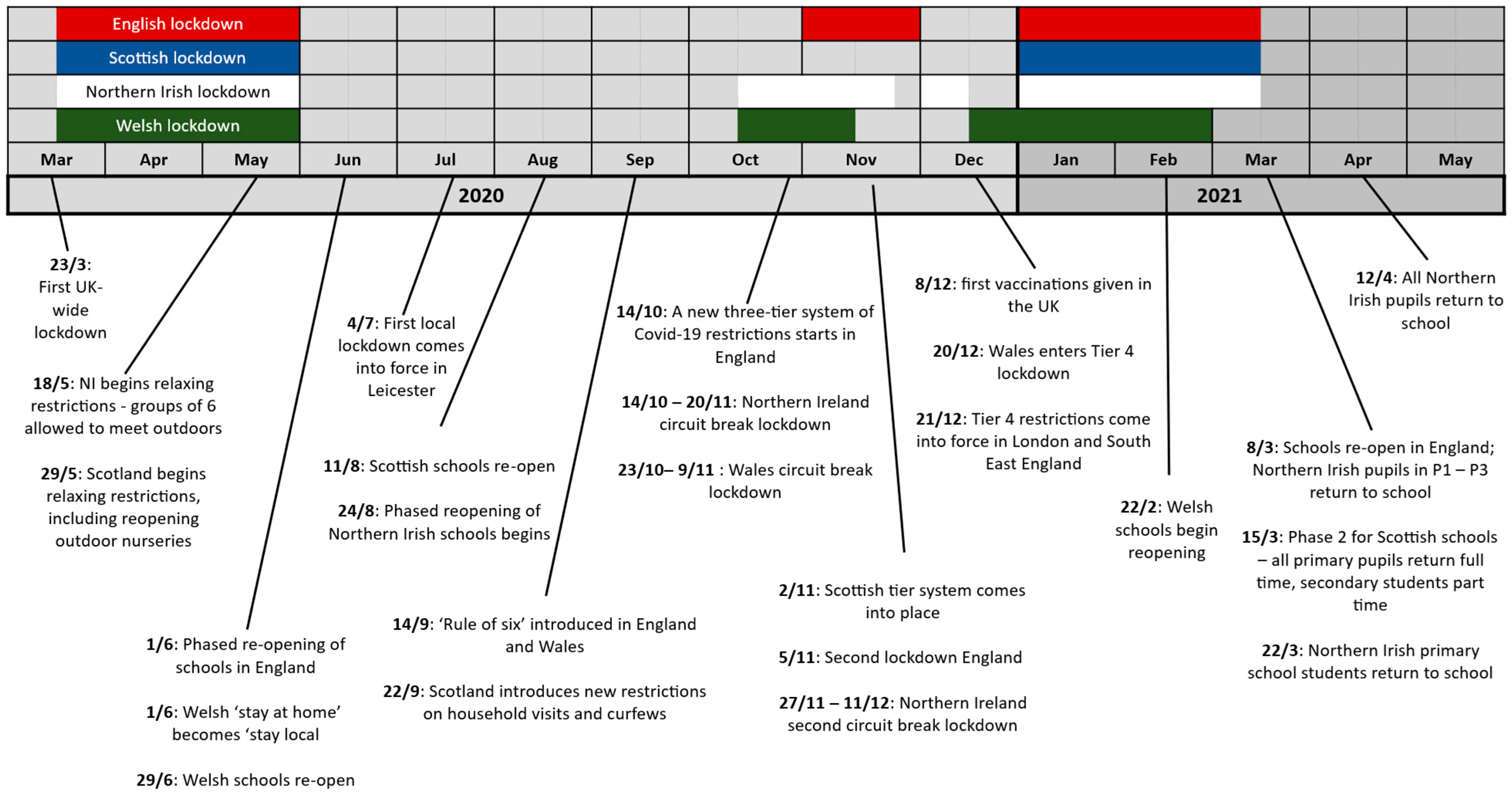

A focus group guide was developed (see

Supplementary S3) and was piloted online prior to the focus groups, resulting in minor restructuring to reduce the focus group length. During the first part of the focus group, participants discussed changes in their diet, daily routine, and reasons for change during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the second part of the focus group, participants drew the trajectory of change in their diet and lifestyle over the course of the pandemic using Google Slides as a tool to encourage in-depth discussion. The participants were given a generic timeline as a discussion prompt (see

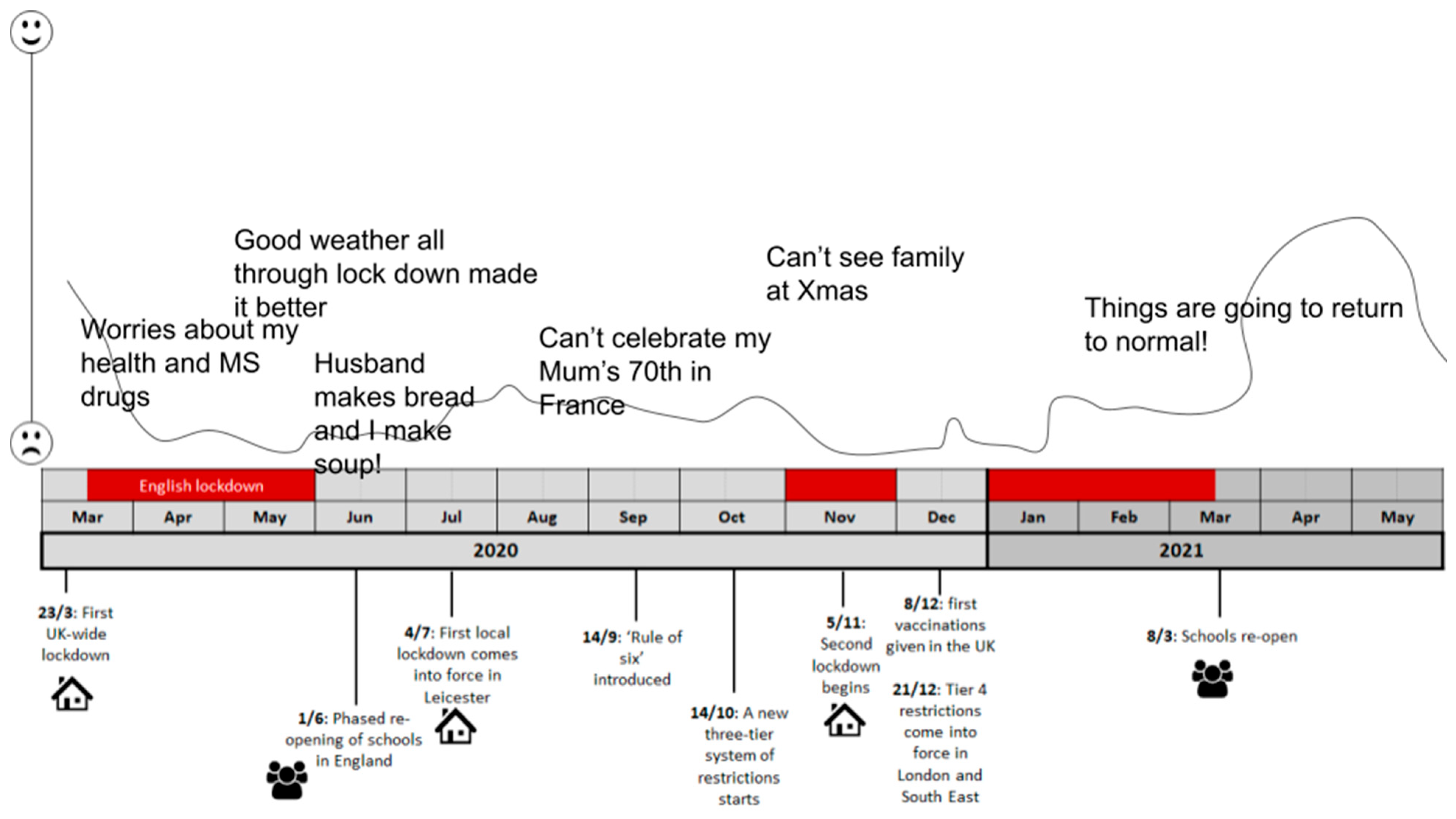

Figure 2), depicting milestones such as initiation of lockdowns, closure and opening of schools, and restrictions around physical activity.

After drawing the trajectories, all participants were asked to describe their drawings to the group, highlighting any changes that were made to diet or lifestyle, reasons for the changes, and whether these changes remained. In the third part of the focus group, participants discussed changes implemented to improve the sustainability of their diet and lifestyle. In the final part of the focus group, participants discussed drivers of change, and co-produced ideas and methods for helping people to cope during times of stress, such as during a pandemic. Informed by the COM-B framework [

29], the participants were asked to discuss opportunities (physical and social), capabilities (physical and psychological), and motivation (reflective and automatic).

The focus groups lasted between 45 and 90 min. All participants gave written and oral consent to take part before the focus groups commenced. The discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed upon completion. Participants were advised to keep their microphone and video on throughout the session to facilitate dialogue; however, only audio was recorded for analysis.

The audio recordings from the focus groups were transcribed and then analyzed using thematic analysis [

49], using the COM-B model as a lens for the analysis. This method facilitated the systematic identification and exploration of recurring themes and patterns within the participants’ responses, that could then be grouped according to capability (C), opportunity (O), and motivation (M). Through a process of data familiarization, code generation, theme development, review, and refinement, the study sought to uncover nuanced insights into the reasons behind dietary changes, coping strategies, and perceptions of wellbeing among the participants. This approach ensured a comprehensive and structured examination of the qualitative data, contributing valuable depth and context to the study’s findings. The data are presented in the form of adapted pen profiles, to summarize the data and allow for reader interpretation [

50].

2.3. Survey Data Analysis

The survey data from Survey 1 and 2 were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 25. Food security, ISS, stress, cohesion in society, coping positive, and emotional eating scores were calculated. Descriptive statistics were produced to explore the demographic composition of the sample. We also applied the COM-B model to the data by grouping risk and protective factors to reflect capability, opportunity, and motivation to eat healthily and sustainably. We did not measure all potential factors representing capacity, opportunity, and motivation but focused on variables of significance for the COVID-19 crisis. We therefore primarily focused on opportunity and on motivational factors that include, for instance, stress and emotional eating [

51].

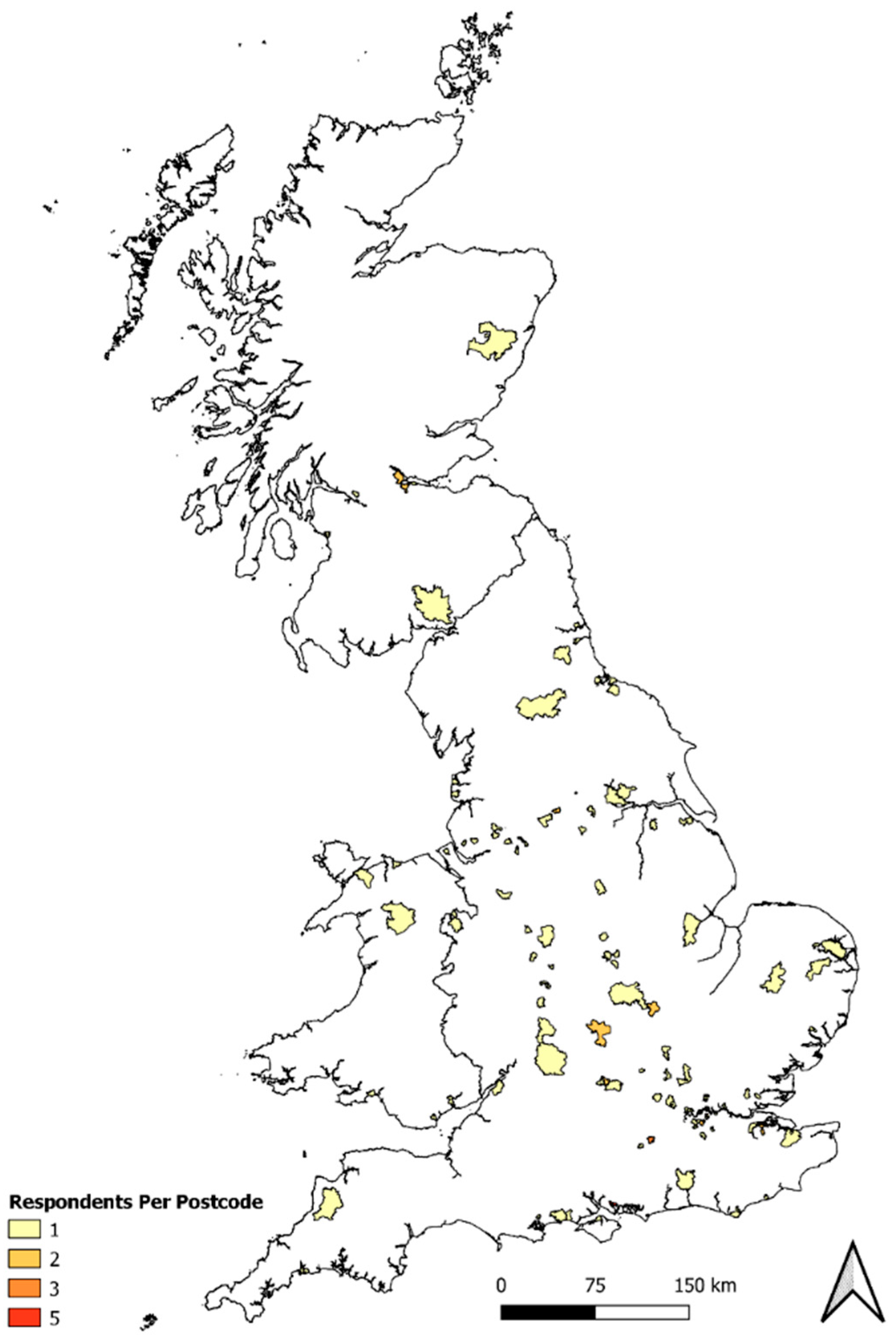

Geospatial Data

Geospatial analyses were performed in the R programming language and Quantum GIS (QGIS), with all work carried out using the British National Grid CRS (EPSG:27700) [

52]. Postcode data from the OS Code Point with Polygon (CPP) [

53] dataset were first parsed and grouped by outbound postcodes before clipping to the ONS Coastal Boundary file to remove polygon sections over water that distorted areal analysis—due to the absence of data for Northern Ireland in the CPP dataset, NI responses were excluded from further geographical analysis. Artificial “Vertical Street” postcode polygons hard coded in the CPP source files were dissolved prior to analysis to avoid intersection conflicts between datasets. For situations where Vertical Streets lay directly on the boundary geometry between postcodes, postcode and Vertical Street polygons were merged in QGIS based on the largest shared common boundary. Greenspace data sourced from the OS Open Greenspace dataset were then aggregated, where applicable, from multi-part to single-part polygons based on shared attribute ID prefixes. Finally, an overlap analysis in QGIS was performed to determine the proportion of greenspace present in each postcode polygon. This final greenspace proportion was then used to assess potential postcode-level correlations between access to greenspace and the various dietary/behavioral measures.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated lockdowns and restrictions impacted individuals worldwide, resulting in a range of adjustments to daily lives, and dynamics at work and in the home. Parents encountered myriad challenges, such as having to homeschool children and dealing with home working arrangements, which may have resulted in greater levels of stress and impacted on their wellbeing. Nonetheless, there exists a dearth of research that explores the multifaceted repercussions of the pandemic on parental wellbeing, dietary patterns, and stress levels.

The aim of this study was first to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted dietary choices and wellbeing amongst parents of children under 18 years of age in the UK, and second, to examine risk factors for impaired diets and increased stress, and identify coping mechanisms used to mitigate against negative impacts of the pandemic on diet, health, and wellbeing. While the COVID-19 pandemic was used as a case study, we view this as providing useful insights into other high-stress, low-opportunity scenarios, which could come about for a range of different reasons, such as the cost-of-living crisis, periods of civil unrest, or climate catastrophes.

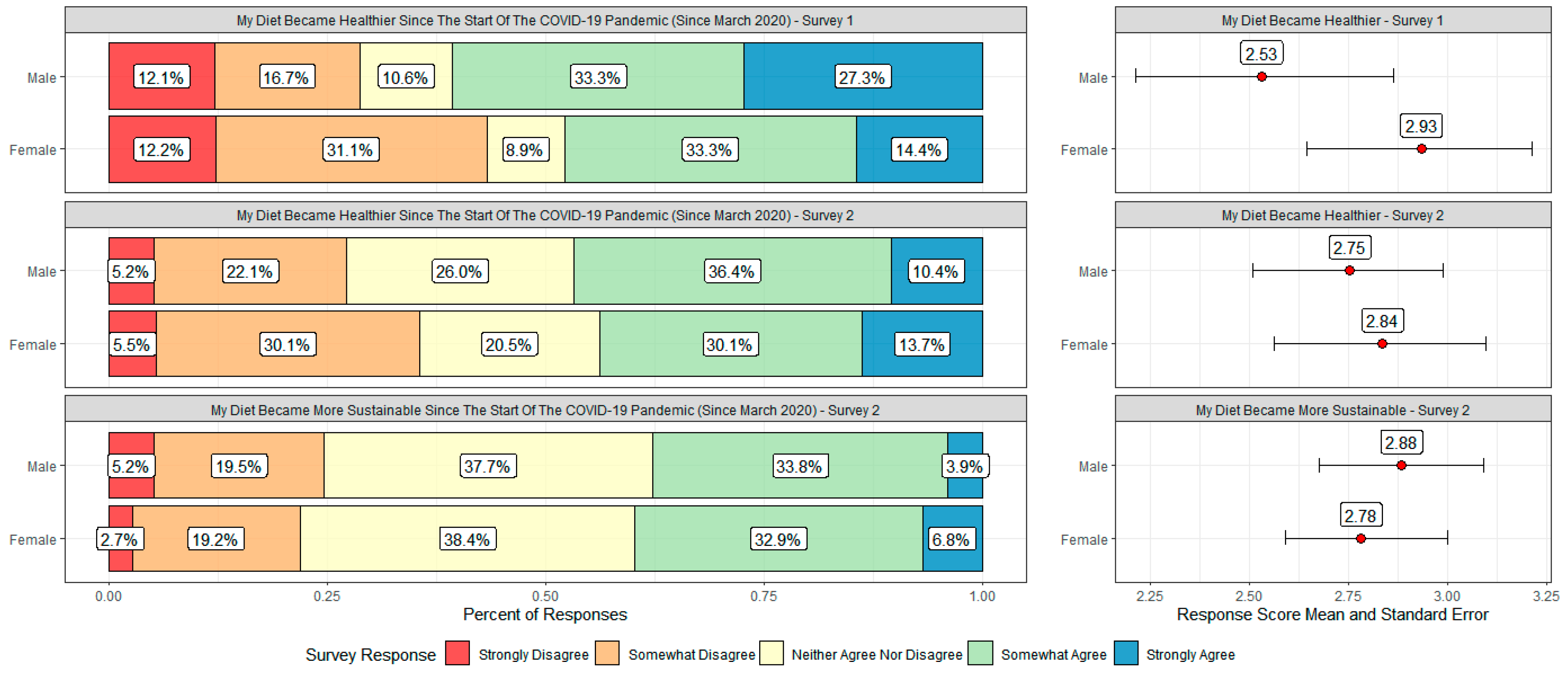

Data captured in the present study suggest that whilst dietary changes during COVID-19 were reported by many participants in the surveys and focus groups, these changes were relatively minor, with averages remaining below 1 unit, e.g., slightly elevating average consumption of fruits (0.3), vegetables (0.7), and fish (0.3), and red meat (0.16) consumption. Conversely, the pandemic prompted an overall reduction in processed meat (0.3) and crisps (0.65) consumption, which contradicts previous research that indicated increases in processed foods, and snack foods [

17]. The dietary changes in the current study were minor and may indicate high resilience of participants in maintaining relatively stable dietary patterns [

55,

56]. The findings also align with some previous research which indicates that there were widespread increases in the consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables [

13,

57] and homemade meals [

58], with reduced consumption of comfort or fast foods [

13,

58], and alcohol [

13] during the pandemic.

Importantly, changes in dietary intake and behaviors were most apparent amongst participants most at risk of food insecurity in both the survey and focus group, with opportunity (e.g., time to cook) mentioned frequently. Although the attrition of those most at risk of food insecurity between surveys 1 and 2 necessitates cautious interpretation, such a finding could indicate the importance of providing targeted support in helping people at risk of food insecurity to deal with changes to food access, as well as changes to their financial stability.

Participants in the survey and focus groups reported that drivers of dietary changes were multifaceted, covering capability (e.g., shielding restricting ability to go shopping), opportunity (e.g., time, food access and availability), and motivation (e.g., health concerns, stress and mental health challenges) related factors. More time to prepare food and cook at home drove dietary change for those used to long commutes, a feature found by other researchers in relation to home cooking during the pandemic [

59]. Ability to access food was another core consideration, with the need for grocery delivery slots to be available to those at risk, and the importance of supply chains maintaining availability of healthy, sustainable foods highlighted. Financial considerations also played a role, underscoring the need for affordability-focused interventions. Previous research has noted that financial challenges and being at risk of food insecurity led to alterations in shopping and eating habits [

28]. Another driver of change for some participants was to improve personal health, supporting previous research by Marty et al. [

16], whilst others stated that they became more conscious of the need to promote environmental sustainability. Meal planning and preparation were key strategies for avoiding waste and making the most of the food available, aligning with personal motivations to promote wellbeing and health.

Significantly, the pandemic appeared to have resulted in a heightened awareness of individual priorities, with more than 60% of respondents saying that COVID-19 had helped them to identify their priorities. This realization reflects the profound impact of the pandemic on individuals’ lives and values, influencing their dietary choices and fostering a heightened consciousness of personal wellbeing and priorities. These insights extend beyond the study’s scope, inviting further exploration into the intricate relationships between external crises and personal transformations.

Within the realm of protective and positive factors associated with healthier and more sustainable diets, several noteworthy correlations emerge. Participants’ mean social cohesion score is linked with healthier dietary choices during the pre-COVID-19 period. Moreover, heightened motivation to consume healthy foods following the pandemic’s onset aligns with healthier and more sustainable dietary patterns at multiple time points. Negative factors related to less healthy and sustainable diets are correlated with increased mean COVID-19 stress scores, underscoring the potential impact of stress on dietary choices during challenging periods. These correlations collectively offer insights into the intricate relationships between psychosocial factors, stress, and dietary behaviors. This supports previous research which highlighted that poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with an increase in unhealthy eating habits [

60]. While the inability to establish causal relationships underscores the need for caution, these findings provide a foundation for further investigations that could unveil the complex interdependencies shaping individuals’ health and sustainability choices during times of crisis. Emotional functioning emerged in our study as a consistent predictor of stress, with food security likely influential. Such findings underscore the significance of maintaining a health-conscious approach during periods of stress and may provide a rationale for the development of further specific dietary support interventions, particularly during periods of high stress. The findings also highlight the importance of reducing stress by limiting food insecurity.

When looking at the impact of the pandemic on wellbeing, the findings indicate that there may be a potential positive influence of self-reported level of engagement with nature, something that only some of the participants had the opportunity to do during the COVID-19 associated lockdowns. While the available greenspace detail in the present study, constrained by four-digit postcodes due to ethics board restrictions, limits granularity and makes discerning clear patterns difficult, this finding supports previous literature which has highlighted the impact of access to greenspace in influencing health and wellbeing outcomes [

61]. This warrants further exploration and a more detailed investigation into its nuances and effects on individuals’ experiences and stress levels.

The study’s exploration of coping strategies offers a promising avenue for promoting resilience during times of stress. Notably, the most frequently deployed coping strategies from Survey 2 included home cooking, meal planning, watching TV/films, increasing exercise, and engaging in gardening. Data from the focus groups indicated that food was also used as a coping strategy, reflecting the intertwined relationship between emotional states and dietary choices [

16], reinforcing the broader literature on stress-related eating patterns [

27].

Negative dietary changes were driven by boredom, financial constraints, stress, and loneliness, while positive changes stemmed from increased time for activities like exercise and cooking, alongside the motivation to enhance health. Reducing feelings of stress was an important part of reducing emotional eating. Whilst these strategies could be developed into interventions to support people in times of future stress and change in managing stress and maintaining healthy behaviors, it is important to recognize that these strategies might be skewed towards those who are food secure, given our sample population, and distinct support mechanisms for the food insecure may be necessary.

Beyond the aforementioned points, this study also offers theoretical contributions to the application of behavioral models in crisis contexts. By using the COM-B framework to analyze coping and dietary behavior’s during the COVID-19 pandemic, we demonstrate the model’s utility beyond structured individual interventions and into real-world, high-stress scenarios. The findings illustrate how changes in physical capability (e.g., shielding), opportunity (e.g., food access, social support), and motivation (e.g., emotional regulation) intersect to shape behavior under pressure. This suggests that behavioral frameworks such as COM-B could usefully inform both the analysis of (mal-)adaptive responses in crises and the design of targeted public health strategies aimed at strengthening behavioral resilience.

Limitations of the Research

Whilst the findings from this research are novel and offer useful insights into other high stress scenarios, the research discussed is not without limitations. These limitations offer insights into the scope and context of the research, allowing for a balanced understanding of its contributions, and also highlight where further research could be conducted.

First, despite achieving an equal participation of males and females, the participant sample’s demographic composition may limit the generalizability of the findings. A lack of ethnic diversity and a predominantly food-secure population could affect the extent to which the results can be extrapolated to more diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. This underlines the need for caution when applying the findings to broader populations.

The study’s survey design and analysis methodology also introduce limitations. The sample size, although suitable for the conducted analyses, might restrict the power to detect subtle effects within specific subgroups. The limited diversity within the sample may also hinder the identification of potential nuances in dietary changes and coping mechanisms across different demographic segments. The timing of the survey implementation, conducted during specific periods of the pandemic, might not capture the full spectrum of experiences throughout the crisis. Although it is possible that long recall periods could introduce recall bias, affecting the accuracy of participants’ responses and perceptions of their dietary habits and coping strategies, there is research indicating that to the contrary, a longer period may potentially result in more information recalled, and lower bias in that information [

62]. The attrition of food-insecure participants between the two survey phases raises concerns about potential bias in the results. This loss to follow-up may impact the representation of individuals who faced heightened challenges during the pandemic, potentially affecting the conclusions drawn from the data. The investigation into greenspace and its association with wellbeing offers preliminary insights, yet a more detailed assessment of this relationship is warranted.

A further limitation relates to the lack of a control or comparison group, such as non-parents. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. However, our focus on parents was intentional, as this group faced distinct and heightened challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, including increased caregiving demands, disrupted routines, and altered access to food. While the results cannot be assumed to apply to all population groups, they provide transferable insights into how individuals in high-stress caregiving roles navigate dietary risks and resilience, offering value for both targeted interventions and future comparative studies.

However, connecting with participants at multiple time points across the pandemic, a gender balanced sample, and the inclusion of focus groups to discuss the experiences of those surveyed in more depth, are strengths in our data. In summary, while the study contributes valuable insights into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dietary behaviors, wellbeing, and coping mechanisms among UK parents, consideration of study context is necessary. Addressing these limitations in future research endeavors will further enhance the depth and breadth of understanding in this complex field.