A No-Regrets Framework for Sustainable Individual and Collective Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty

Abstract

1. Introduction

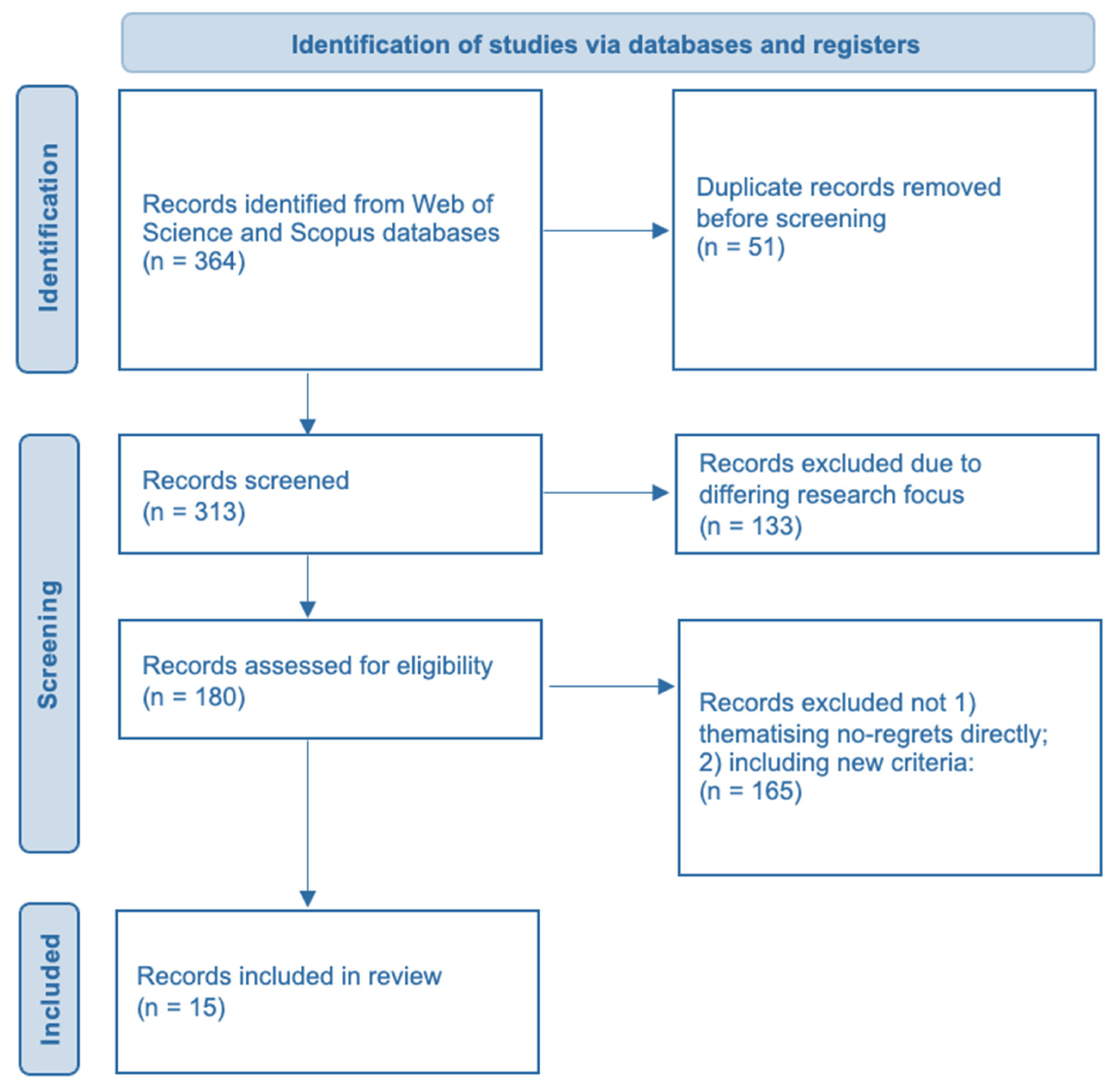

2. Methodology

2.1. Systematic Review of No-Regrets Criteria

2.2. Literature Review of No-Regrets Actions

- Several actions were found to be of higher economic cost, such as installing flood barriers, creating green roofs, or similar. The fact that they are of high cost should have excluded them. However, in this framework, costs are not considered solely but in combination with their effectiveness. This may often be the case for increasing building resilience or Nature-based Solutions (NbS) (e.g., green roofs). For the first case, these actions may not be regretted because they are very efficient in damage mitigation. Similarly, for NbS, it could be argued that they are costly but more efficient in terms of flood mitigation, and, additionally, they can entail many co-benefits. Hence, costs need to be considered in a cost-effectiveness/benefit framework where benefits can be direct (e.g., flood reduction) or co-benefits (e.g., health benefits).

- Similarly, some actions may not be easy to implement (e.g., because it can be difficult to motivate others for collective action), do not have co-benefits, or are not of a collective character. However, their effectiveness in hazard reduction or damage mitigation could be argued to outweigh the lack of some no-regrets values.

3. The No-Regrets Framework for Individual and Collective Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty

3.1. No-Regrets Criteria

3.1.1. Robust but Flexible

3.1.2. Cost-Effectiveness

3.1.3. (Co-)Benefits

3.1.4. Easy to Implement

3.1.5. Collective Action

3.2. No- and Low-Regrets Actions for Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty

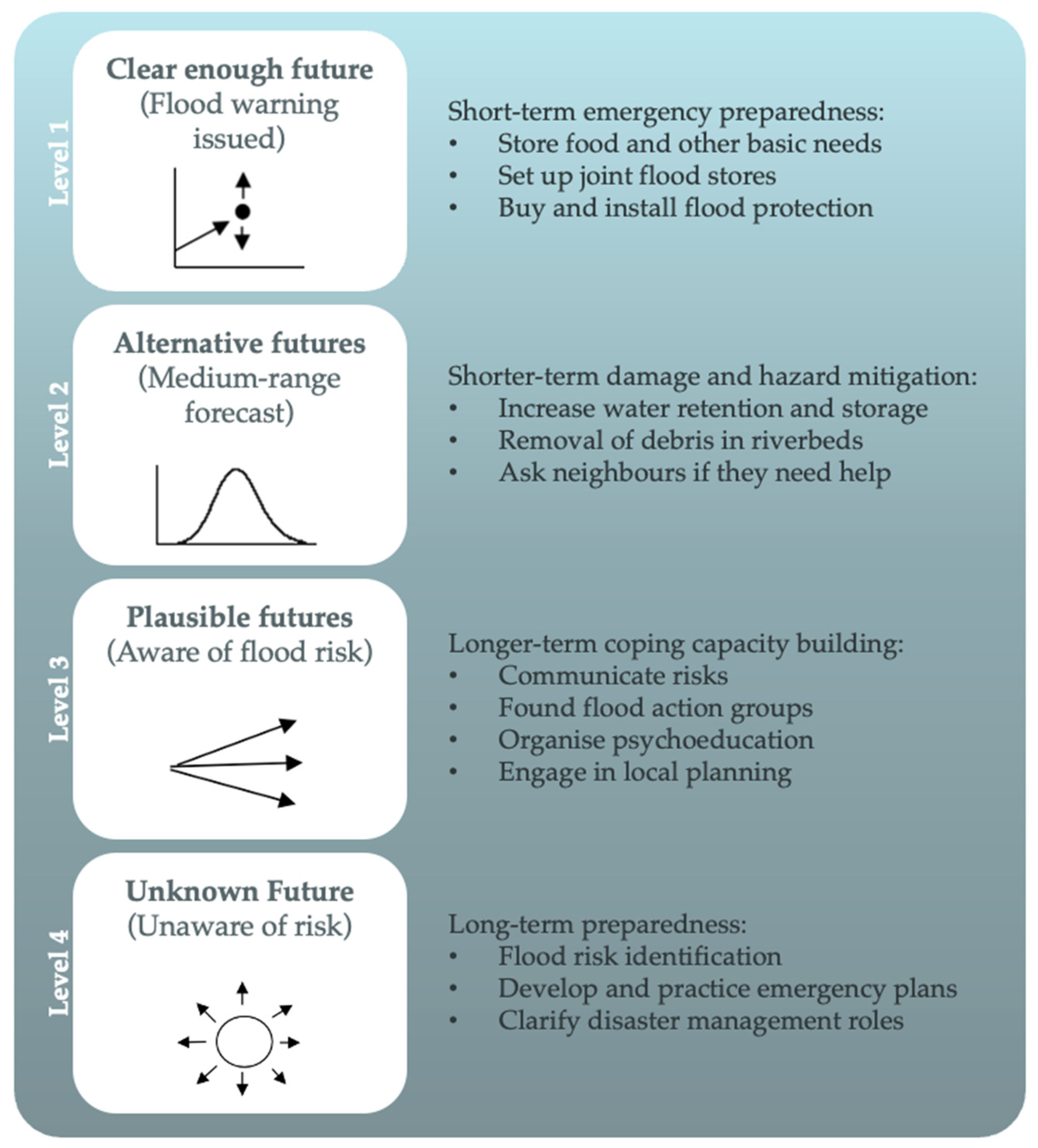

- Uncertainty: This level is often referred to as deep uncertainty, meaning that it is unknown how the future looks, as there are uncountable different scenarios. This level also includes disasters ranging from more common hazards such as flooding to unknown hazards.

- Time: Anytime—not related to a specific event or risk.

- Disaster preparedness: Long-term preparedness is needed to focus on gaining knowledge on potential future scenarios and building capabilities to cope with (surprising) emergency situations.

- No- and low-regrets action focus: Gaining knowledge on local hazards, risks, disaster management, and early warning; developing emergency response capabilities; connecting with other citizens and communities; increasing awareness, imagination, and action on climate adaptation; observing the weather and environment to develop local thresholds and awareness of changes; enhancing psychological preparedness for emergencies; and considering economic preparedness.

- Uncertainty: In this level, citizens are aware of local risk, but there is a great uncertainty around the timing, magnitude, and impact of a hazard, which can be translated into different scenarios (e.g., flood return periods).

- Time: Anytime—after becoming aware of the risk.

- Disaster preparedness: Based on these scenarios different long-term preparedness actions can be taken to reduce the risk.

- No- and low-regrets action focus: Founding action groups; raising awareness within your community; assessing local disaster risk; reducing disaster risk with NbS; increase collaboration in risk management between the community and local authorities; developing community emergency plans and practices; ensuring individual economic preparedness; psychological preparedness; increasing property resilience; and stocking up of emergency resources.

- Uncertainty: The hazard occurrence is probable, but there might be an alternative future. Uncertainty arises due to the timely or spatially manner of the hazard, or to its impact.

- Time: Days (or weeks) before a hazard strikes.

- Disaster preparedness: As a hazard is becoming likely, a shift too short-term preparedness is initiated.

- No- and low-regrets action focus: Preparing the home and garden for potential water intrusion; setting up an evacuation plan and kit; and raising awareness of the probable hazard within the community.

- Uncertainty: Weather forecasts provide a clear (enough) prediction about the approaching hazard; thus, the uncertainty about the hazard is low.

- Time: Hours up to few days before the hazard strikes.

- Disaster preparedness: Due to the imminent hazard, actions are focused on preparing for response and recovery, as well as reducing damage.

- No- and low-regrets action focus: Last preparations such as placing sandbags; installing pumps; switching off gas, etc.; or reparking the car.

4. Discussion

4.1. Long-Term Preparedness

4.2. Contextual Transferability

4.3. Psychological Preparedness

4.4. Towards Behaviour Change

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Long and Short-Term Preparedness Actions

| Action | Unknown Future | Plausible Future | Probable Alternative | Clear Future | Individual (I)/Collective (C) | Robust (R)/Flexible (F) | Cost-Effective | Benefits | Likely Co-Benefits | Easy to Implement | Probable Regret Level | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familiarise yourself with local risk areas—is your home in a risk area? | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Co-benefits: motivation for flood preparedness; disbenefit: potential anxiety | E | No regret | [27] | ||||

| Future visioning and hazard imagination workshop | C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Co-benefits: enhanced self-efficacy, collective agency, challenge anticipation, long-term vision; disbenefit: potential anxiety | E-M | No regret | [71,72] | ||||

| Developing a household and/or neighbourhood emergency plan | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [27] | ||||

| Evacuation (when to evacuate; where to go; which route to take; where to find shelters) | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [16,59,73] | ||||

| Practice household emergency plan | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [27] | ||||

| Learn how the local or national early warning systems works; co-develop a system if it is not available at the community level | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Peace of mind | E-M | No/low regret | [74] | ||||

| Learn about and clarify roles and responsibilities in disaster context | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Self-responsibility; empowerment; social cohesion | E-M | No regret | [75] | ||||

| Be attentive to weather warnings and updates | I | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Gaining an understanding of local weather patterns and thresholds | E | No regret | [76] | ||||

| Lobby against urban developments that will increase runoff onto one’s property | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge; flood mitigation | Raising awareness within the community and authorities | M | No/low regret | [77] | ||||

| Communicate interventions within community including vulnerable neighbours; make sure information is understandable by as many people as possible by including indigenous community members | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Peace of mind; anticipation guilt of not having helped; increased self-responsibility | E | No regret | [59,78] | ||||

| Start a conversation about how an emergency might affect your local community | C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Peace of mind; increasing social capital | E | No regret | [63] | ||||

| Identify climate champions in your community | C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge | Motivation for action-taking | E | No regret | [79] | ||||

| Establish climate schools (e.g., for farmers, young generation) | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–medium | Awareness and knowledge | Motivation for action-taking; self-responsibility; empowerment | E-M | No/low regret | [80] | ||||

| Develop a climate youth club | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge | Motivation for action-taking; self-responsibility; empowerment | E-M | No/low regret | [73] | ||||

| Restore wetlands | C | R, F | Cost: low–high Efficacy: medium–high | Flood mitigation | Increasing biodiversity; community cohesion; re-creational area | M-D | Low regret | [47,81] | ||||

| Increase local water retention capacity by planting trees and local species | C | R, F | Cost: low–high Efficacy: medium–high | Flood mitigation | Peace of mind; increasing biodiversity; community cohesion/well-being | M-D | Low regret | [82,83,84] | ||||

| Increase local water storage capacity with, e.g., detention and retention ponds, rechannelling streams, etc. | C | R, F | Cost: low–high Efficacy: medium–high | Flood mitigation | Peace of mind; increasing biodiversity; community cohesion/well-being | M-D | Low regret | [47,82,83,84] | ||||

| Removal of debris, litter, foliage, or similar from river sides; dredging riverbed | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Flood mitigation | Peace of mind; social cohesion; well-being | E-M | No/low regret | [59,76,84,85] | ||||

| Start monitoring rainfall amounts, water depths, etc. with low-cost sensors, and establish your own local thresholds | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge | Peace of mind; gaining an understanding of local weather patterns and thresholds | E | No/low regret | [27,86] | ||||

| Create monitoring networks | C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge | Social connectedness; common understanding of local weather patterns and thresholds | M | Low regret | [47] | ||||

| Observe the environment for changes | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Gaining an understanding of local changes | E | No regret | [73] | ||||

| Organise psychoeducation for community members on stress reactions and coping to reduce distress and promote adaptive functioning | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–medium | Coping capacity | Peace of mind; better understanding of one’s own behaviour and emotions | E | No regret | [78] | ||||

| Create a self-care plan in advance of a disaster or emergency. Anticipating, monitoring and understanding your own and your loved ones’ reactions will really help during an emergency | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind; increasing psychological strengths | E | No regret | [63] | ||||

| What are the things in your life that cannot be replaced, and that have great meaning for you or your loved ones? Think about ways you can protect these things in an emergency | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [63] | ||||

| Diversify household incomes | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–high Efficacy: medium-high | Reducing economic vulnerability | Peace of mind | M-D | Low regret | [59,83,87] | ||||

| Learn about government schemes (e.g., for agriculture and farming practices) | I | R, F | Cost: no | Reducing economic vulnerability; flood mitigation | Learning/adopting new practices; reduced costs; increased revenue | E | No regret | [59] | ||||

| Adopt flood resistant/climate resilient agricultural practices | I | R, F | Cost: no–high Efficacy: low–high | Reducing economic vulnerability | Peace of mind; knowledge of new practices | E-D | Low regret | [59] | ||||

| Preparing for power outages by developing an off-grid energy supply, having battery back-ups | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–medium | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No/low regret | [59] | ||||

| Store food and other items of basic need in a safer place; increase stilted food storages | I | R, F | Cost: no–low | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No/low regret | [59] | ||||

| Keep drains clear | I | R, F | Cost: no Efficacy: low–medium | Flood mitigation; damage mitigation | Peace of mind; physical exercise | E | No regret | [88] | ||||

| Increasing property water retention capacity (e.g., remove paving in the garden; plant local species; green roofs; rain gardens; tree planting and protection; bioretention cells; vegetated swales) | I | R, F | Cost: low–high Efficacy: low–high | Flood mitigation | Aesthetics; promoting biodiversity; improving air quality | E-M | Low regret | [34,59,82,89,90] | ||||

| Increasing property water storage capacity (e.g., tanks, retention pond) and harvest rainwater | I | R, F | Cost: low–high Efficacy: low–high | Flood mitigation | Water storage for watering plants during dry periods; biodiversity | M-D | Low regret | [16,90] | ||||

| Act as a flood warden | I | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Increasing self-responsibility; empowerment; improving communication between citizens and authorities | M-D | No/low regret | [76] | ||||

| Join or found a flood action group | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Increasing self-responsibility; empowerment; improving communication between citizens and authorities | E | No regret | [76] | ||||

| Develop hazard and vulnerability maps based on local knowledge; extend already existing hazard maps with local knowledge | C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Increasing social capital and social cohesion | E-M | No/low regret | [47] | ||||

| Engage in the planning and implementation of local strategies and actions for flood mitigation | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; flood mitigation | Peace of mind; anticipation guilt of not having helped; increasing self-responsibility | E-M | No/low regret | [59,73,76,91,92] | ||||

| Be politically active to guide the community towards flood preparedness | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Peace of mind; increasing self-responsibility; empowerment | E-M | No/low regret | [76] | ||||

| Create a joined neighbourhood flood network; mutual help associations | C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Peace of mind; increasing social capital and cohesion | E | No regret | [57,83] | ||||

| Develop a community emergency plan including evacuation meeting points | C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Peace of mind; increasing social capital and cohesion | E | No regret | [91,93] | ||||

| Set up joint flood stores with tools and materials for emergency cases | C | R, F | Cost: no–medium | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E-M | No/low regret | [76] | ||||

| Conduct joint flood drills with neighbours | C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Peace of mind; increasing social capital and cohesion | E | No regret | [76] | ||||

| Educate younger generations on traditional flood protection methods | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Awareness and knowledge; coping capacity | Peace of mind; preservation of traditions | E-M | No/low regret | [94] | ||||

| Move to a no-risk area | I | R | Cost: high Efficacy: high | Reducing economic vulnerability | Peace of mind | D | Low regret | [76,95] | ||||

| Obtain or renew a property insurance (for flooding) | I | R, F | Cost: medium–high Efficacy: medium–high | Reducing economic vulnerability | Peace of mind | E | Low regret | [13,16,34,57,91] | ||||

| Encourage your neighbour to purchase an insurance (for flooding) | I, C | R, F | Costs: no | Reducing economic vulnerability | Good neighbourhood relations; peace of mind | E | No regret | [91] | ||||

| Try to influence the property owner/housing cooperative to take preparedness measures | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E-M | No/low regret | [77] | ||||

| Building a house in a flood risk area, consider elevating the ground floor, floating options, stilts, water insensitive materials, suitable positioning of utility networks (e.g., electricity, drinking water, sewage), placing a tub around the basement, etc. | I | R | Cost: high Efficacy: high | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | M-D | Low regret | [47,91,96] | ||||

| Installation of backflow preventers | I | R | Cost: low–high Efficacy: medium | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | M-D | Low regret | [76,95] | ||||

| Adapting the building use and interior fitting | I | R, F | Costs: no–high Efficacy: medium | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E-M | No/low regret | [57,95,97] | ||||

| Buying, maintaining pumps and learning how to use them | I | R, F | Cost: low | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [76,77] | ||||

| Buying sandbags and making them easily accessible | I, C | R, F | Cost: low | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [76,77] | ||||

| Buying and installing stationary or mobile flood barriers | I | R | Cost: medium–high Efficacy: medium–high | Coping capacity; damage mitigation | Peace of mind; potential price reduction for flood insurance | E-M | Low regret | [16,57,59,77,91,95] | ||||

| Knowing where to park the car in an emergency | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [57,88] | ||||

| Communicate dangerous behaviour including going into flooded basements, walking or driving in flood water | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and education | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [27] | ||||

| Talk to your neighbour about flood preparedness and mitigation | I | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Peace of mind; good neighbourhood relations | E | No regret | [91] | ||||

| Knowing your neighbours and who might need support in case of an evacuation or in long- and short-term preparedness | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [76,77,91] | ||||

| Redirect water flow around the house | I | R, F | Cost: no | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [98] | ||||

| Keep feed for livestock in a waterproof place | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [89,99] | ||||

| Knowing where to evacuate livestock to | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [89,100] | ||||

| Seek guarantees that the area will get special attention from rescue authorities in case of a new emergency | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Reducing vulnerability | Peace of mind; increasing awareness | M | Low regret | [77] | ||||

| Moving valuable items, documents, etc. upstairs | I | R, F | Cost: no | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [57,76,97] | ||||

| Organising temporary accommodation or knowing where shelters are | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–medium Efficacy: high | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [27,59,76] | ||||

| Preparing an emergency kit including important documents, medicines, clothes, water, and food, etc.) | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [59,73] | ||||

| Having medicines for pet and livestock prepared | I | R, F | Cost: no | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [89] | ||||

| Keep ropes to make boats from banana trees | I, C | R, F | Cost: no–low | Coping capacity | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [59] | ||||

| Communicate flood warnings within the community (e.g., via social media); avoid the spreading of fake news | I, C | R, F | Cost: no | Awareness and knowledge | Peace of mind; prevention of guilt | E | No regret | [77,88] | ||||

| Switch off gas, electricity, etc.; protect oil tanks; seal air conditioning or ventilation systems; secure dangerous substances | I | R, F | Cost: no | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [57,95] | ||||

| Waterproof your home by installing flood barriers, pumps, or placing sandbags around the house | I | R, F | Cost: no–low | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E-M | No/low regret | [16,57,59,76,91,95] | ||||

| Reparking the car | I | R, F | Cost: no | Damage mitigation | Peace of mind | E | No regret | [27] |

References

- UNDRR. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2022: Our World at Risk: Transforming Governance for a Resilient Future; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, D.; Liao, K.-H. Learning from Floods: Linking flood experience and flood resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchau, V.A.W.J.; Walker, W.E.; Bloemen, P.J.T.M.; Popper, S.W. (Eds.) Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Uncertainty. 2024. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/uncertainty (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- van der Keur, P.; van Bers, C.; Henriksen, H.J.; Nibanupudi, H.K.; Yadav, S.; Wijaya, R.; Subiyono, A.; Mukerjee, N.; Hausmann, H.-J.; Hare, M.; et al. Identification and analysis of uncertainty in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in South and Southeast Asia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 16, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunnasr, Y.; Hamin, E.M.; Brabec, E. Windows of opportunity: Addressing climate uncertainty through adaptation plan implementation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, K.; Gabrys, J. Climate change and the imagination. WIREs Clim. Change 2011, 2, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothmann, T.; Reusswig, F. People at Risk of Flooding: Why Some Residents Take Precautionary Action While Others Do Not. Nat. Hazards 2006, 38, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.; Crews, C.W.; Georgia, P.; Lieberman, B.; Melugin, J.; Seivert, M.-L. Greenhouse Policy Without Regrets. 2000. Available online: https://cei.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/Jonathan-Adler-Greenhouse-Policy-Without-Regrets-A-Free-Market-Approach-to-the-Uncertain-Risks-of-Climate-Change.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Walker, W.; Harremoës, P.; Rotmans, J.; van der Sluijs, J.; van Asselt, M.; Janssen, P.; von Krauss, M.K. Defining Uncertainty: A Conceptual Basis for Uncertainty Management in Model-Based Decision Support. Integr. Assess. 2003, 4, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernau, M.E.; Makofske, W.J.; South, D.W. Review and impacts of climate change uncertainties. Futures 1993, 25, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plume, R.W. The Greenhouse Effect and the Resource Management Act, as Related to Oil and Gas Exploration and Production. Energy Explor. Exploit. 1995, 13, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heltberg, R.; Siegel, P.B.; Jorgensen, S.L. Addressing human vulnerability to climate change: Toward a ‘no-regrets’ approach. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, H.; Kirkland, J.; Viguerie, P. Strategy under uncertainty. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Auld, H.; MacIver, D.; Klaassen, J. Adaptation Options for Infrastructure Under Changing Climate Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE EIC Climate Change Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 9–12 May 2006; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S. Strategies to adapt to an uncertain climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J.E.; Rodriguez-Pineda, J.A.; Benignos, M.D. Integrated river basin management in the Conchos River basin, Mexico: A case study of freshwater climate change adaptation. Clim. Dev. 2009, 1, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingem, M.; Rivington, M. Adaptation for crop agriculture to climate change in Cameroon: Turning on the heat. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2009, 14, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, J.; Strixner, L.; Kreft, S.; Jeltsch, F.; Ibisch, P.L. Adapting conservation to climate change: A case study on feasibility and implementation in Brandenburg, Germany. Reg. Environ. Change 2015, 15, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.B.; Brito, J.C.; Crespo, E.G.; Watts, M.E.; Possingham, H.P. Conservation planning under climate change: Toward accounting for uncertainty in predicted species distributions to increase confidence in conservation investments in space and time. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 2020–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusius, J. “Natural” Climate Solutions Could Speed Up Mitigation, with Risks. Additional Options Are Needed. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2019EF001310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, S.; Amado, M.; Ferreira, F. Challenges and Opportunities in the Use of Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Adaptation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debele, S.E.; Leo, L.S.; Kumar, P.; Sahani, J.; Ommer, J.; Bucchignani, E.; Vranić, S.; Kalas, M.; Amirzada, Z.; Pavlova, I.; et al. Nature-based solutions can help reduce the impact of natural hazards: A global analysis of NBS case studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 165824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; UNISDR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck, P.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Kreibich, H.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Long-term development and effectiveness of private flood mitigation measures: An analysis for the German part of the river Rhine. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 3507–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieken, A.H.; Bubeck, P.; Heidenreich, A.; von Keyserlingk, J.; Dillenardt, L.; Otto, A. Performance of the flood warning system in Germany in July 2021—Insights from affected residents. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommer, J.; Kalas, M.; Neumann, J.; Blackburn, S.; Cloke, H.L. Turning regret into future disaster preparedness with no-regrets. EGUsphere 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikopoulos, P.V. Individual and community resilience in natural disaster risks and pandemics (COVID-19): Risk and crisis communication. Mind Soc. 2021, 20, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every, D.; McLennan, J.; Reynolds, A.; Trigg, J. Australian householders’ psychological preparedness for potential natural hazard threats: An exploration of contributing factors. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 38, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entorf, H.; Jensen, A. Willingness-to-pay for hazard safety—A case study on the valuation of flood risk reduction in Germany. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCL. Creating Effective Warnings for All Conference: Panel on Making the Last Mile, the First—Integrating Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches; UCL Warning Research Centre: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, S.C. Planning for an unknowable future: Uncertainty in climate change adaptation planning. Clim. Change 2016, 139, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penning-Rowsell, E.; Korndewal, M. The realities of managing uncertainties surrounding pluvial urban flood risk: An ex post analysis in three European cities. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2019, 12, e12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalau, J.; Torabi, E.; Edwards, N.; Howes, M.; Morgan, E. A critical exploration of adaptation heuristics. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.C.; Renaud, F.G.; Hanscomb, S.; Gonzalez-Ollauri, A. Green, hybrid, or grey disaster risk reduction measures: What shapes public preferences for nature-based solutions? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Summary for Policymakers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.B.; Ragland, S.E.; Pitts, G.J. A process for evaluating anticipatory adaptation measures for climate change. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1996, 92, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, L.; Daly, M.E.; Travis, W.R.; Wilhelmi, O.V.; Klein, R.A. The dynamics of vulnerability: Why adapting to climate variability will not always prepare us for climate change. WIREs Clim. Change 2015, 6, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Solomatine, D. A framework for uncertainty analysis in flood risk management decisions. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2008, 6, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, P.B.; Galloway, G.E.; Hall, J.W. Robust decision-making under uncertainty—Towards adaptive and resilient flood risk management infrastructure. In Flood Risk: Planning, Design and Management of Flood Defence Infrastructure; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2012; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Ding, X.; Shao, W. Integrated assessments of green infrastructure for flood mitigation to support robust decision-making for sponge city construction in an urbanized watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postek, K.; den Hertog, D.; Kind, J.; Pustjens, C. Adjustable robust strategies for flood protection. Omega 2019, 82, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Geng, L.; Rodríguez Casallas, J.D. Mindfulness to climate change inaction: The role of awe, “Dragons of inaction” psychological barriers and nature connectedness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Z.H.; Swartz, M.C.; Lyons, E.J. What’s the Point?: A Review of Reward Systems Implemented in Gamification Interventions. Games Health J. 2016, 5, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommer, J.; Bucchignani, E.; Leo, L.S.; Kalas, M.; Vranić, S.; Debele, S.; Kumar, P.; Cloke, H.L.; Di Sabatino, S. Quantifying co-benefits and disbenefits of Nature-based Solutions targeting Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 75, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baills, A.; Garcin, M.; Bulteau, T. Assessment of selected climate change adaptation measures for coastal areas. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 185, 105059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Kyle, G.T.; Tran, T. Determining social-psychological drivers of Texas Gulf Coast homeowners’ intention to implement private green infrastructure practices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 90, 102090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botzen, W.J.W. Improving Individual Flood Preparedness Through Insurance Incentives. In The Future of Risk Management; Kunreuther, H., Meyer, R.J., Michel-Kerjan, E.O., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kievik, M.; Gutteling, J.M. Yes, we can: Motivate Dutch citizens to engage in self-protective behavior with regard to flood risks. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.; Albarracín, D. Norm theory and the action-effect: The role of social norms in regret following action and inaction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 69, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soetanto, R.; Mullins, A.; Achour, N. The perceptions of social responsibility for community resilience to flooding: The impact of past experience, age, gender and ethnicity. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 1105–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geaves, L.H.; Penning-Rowsell, E.C. ‘Contractual’ and ‘cooperative’ civic engagement: The emergence and roles of ‘flood action groups’ in England and Wales. Ambio 2015, 44, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, L.; Holmes, A.; Quinn, N.; Cobbing, P. ‘Learning for resilience’: Developing community capital through flood action groups in urban flood risk settings with lower social capital. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, J.C. Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy. J. Int. Dev. 2010, 22, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreibich, H.; Seifert, I.; Thieken, A.H.; Lindquist, E.; Wagner, K.; Merz, B. Recent changes in flood preparedness of private households and businesses in Germany. Reg. Environ. Change 2011, 11, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/terminology#R (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Oliver, T.H.; Bazaanah, P.; Da Costa, J.; Deka, N.; Dornelles, A.Z.; Greenwell, M.P.; Nagarajan, M.; Narasimhan, K.; Obuobie, E.; Osei, M.A.; et al. Empowering citizen-led adaptation to systemic climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surminski, S.; Thieken, A.H. Promoting flood risk reduction: The role of insurance in Germany and England. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Ecosystem Based Adaptation: Building on No Regret Adaptation Measures; IUCN: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Höfler, M. Psychological Resilience Building in Disaster Risk Reduction: Contributions from Adult Education. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2014, 5, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Red Cross. Preparing Emotionally for Disasters and Emergencies; Canadian Red Cross: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://www.redcross.ca/how-we-help/emergencies-and-disasters-in-canada/be-ready-emergency-preparedness-and-recovery/preparing-emotionally-for-disasters-and-emergencies (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- APS. Psychological Preparation for Natural Disasters; APS: Saint-Loubès, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stanke, C.; Murray, V.; Amlôt, R.; Nurse, J.; Williams, R. The effects of flooding on mental health: Outcomes and recommendations from a review of the literature. PLoS Curr. 2012, 4, e4f9f1fa9c3cae. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makwana, N. Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abunyewah, M.; Gajendran, T.; Maund, K. Conceptual Framework for Motivating Actions towards Disaster Preparedness Through Risk Communication. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.S.; Grehl, M.M.; Rutter, S.B.; Mehta, M.; Westwater, M.L. On what motivates us: A detailed review of intrinsic v. extrinsic motivation. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 1801–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.; Blackburn, S.; Mantovani, N. Psychological resilience for climate change transformation: Relational, differentiated and situated perspectives. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 50, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommer, J.; Neumann, J.; Kalas, M.; Blackburn, S.; Cloke, H.L. Surprise floods: The role of our imagination in preparing for disasters. EGUsphere 2024, 24, 2633–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, E.; Wylie, R. Collaborative imagination: A methodological approach. Futures 2021, 132, 102788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesche, S.D.; Armitage, D.R. Using qualitative scenarios to understand regional environmental change in the Canadian North. Reg. Environ. Change 2014, 14, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, P.B.; Gatsinzi, J.; Kettlewell, A. Adaptive Social Protection in Rwanda: ‘Climate-proofing’ the Vision 2020 Umurenge Programme. IDS Bull. 2011, 42, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ommer, J.; Blackburn, S.; Kalas, M.; Neumann, J.; Cloke, H.L. Risk social contracts: Exploring responsibilities through the lens of citizens affected by flooding in Germany in 2021. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2024, 21, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlicke, C.; Seebauer, S.; Hudson, P.; Begg, C.; Bubeck, P.; Dittmer, C.; Grothmann, T.; Heidenreich, A.; Kreibich, H.; Lorenz, D.F.; et al. The behavioral turn in flood risk management, its assumptions and potential implications. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, E.; Wamsler, C. Citizen engagement in climate adaptation surveyed: The role of values, worldviews, gender and place. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousse-Lessard, A.-S.; Gachon, P.; Lessard, L.; Vermeulen, V.; Boivin, M.; Maltais, D.; Landaverde, E.; Généreux, M.; Motulsky, B.; Le Beller, J. Intersectoral approaches: The key to mitigating psychosocial and health consequences of disasters and systemic risks. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2023, 32, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiarani, B.; Handayani, W. The role of local champions in community-based adaptation in Semarang coastal area. J. Pembangunan Wil. Kota 2016, 12, 263. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326480325 (accessed on 9 April 2024). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Butler, J.R.A.; Bohensky, E.L.; Suadnya, W.; Yanuartati, Y.; Handayani, T.; Habibi, P.; Puspadi, K.; Skewes, T.D.; Wise, R.M.; Suharto, I.; et al. Scenario planning to leap-frog the Sustainable Development Goals: An adaptation pathways approach. Clim. Risk Manag. 2016, 12, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NWRM. Benefit Tables; NWRM: Snoqualmie, WA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://nwrm.eu/catalogue-nwrm/benefit-tables (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Chen, C.; Doherty, M.; Coffee, J.; Wong, T.; Hellmann, J. Measuring the adaptation gap: A framework for evaluating climate hazards and opportunities in urban areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafakos, S.; Pacteau, C.; Delgado, M.; Landauer, M.S.; Lucon, O.; Driscoll, P. ARC3.2 Summary for City Leaders. In Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network; Rosenzweig, C., Solecki, W., Romero-Lankao, P., Mehrothra, S., Dhakal, S., Ali Ibrahim, S., Eds.; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mustelin, J.; Klein, R.G.; Assaid, B.; Sitari, T.; Khamis, M.; Mzee, A.; Haji, T. Understanding current and future vulnerability in coastal settings: Community perceptions and preferences for adaptation in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Popul. Environ. 2010, 31, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, A.V.; Brondizio, E.S.; Roy, S.; de Miranda Araújo Soares, P.P.; Newton, A. Adapting to urban challenges in the Amazon: Flood risk and infrastructure deficiencies in Belém, Brazil. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Knapen, L.; Ectors, W.; Aerts, L. Enhancing Learning About Climate Change Issues Among Secondary School Students with Citizen Science Tools. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on E-Science (e-Science), Limassol, Cyprus, 9–13 October 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimkong, H.; Promphakping, B.; Hudson, H.; Day, S.C.J.; Long, L.V. Income Diversification and Household Wellbeing: Case Study of the Rural Framing Communities of Tang Krasang and Trapang Trabek in Stung Chreybak, Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Demant, D.; Peden, A.E.; Hagger, M.S. A systematic review of human behaviour in and around floodwater. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 47, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.A. Being pet prepared saves human and animal lives. Del. J. Public Health 2019, 5, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, M.K.; Samaras, C. A Review of Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty Applications Using Green Infrastructure for Flood Management. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.T.; Edgeley, C.M. Factors influencing flood risk mitigation after wildfire: Insights for individual and collective action after the 2010 Schultz Fire. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.R.A.; Suadnya, W.; Puspadi, K.; Sutaryono, Y.; Wise, R.M.; Skewes, T.D.; Kirono, D.; Bohensky, E.L.; Handayani, T.; Habibi, P.; et al. Framing the application of adaptation pathways for rural livelihoods and global change in eastern Indonesian islands. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. Requirements for Flood Openings in Foundation Walls and Walls of Enclosures; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_tb1_openings_foundation_walls_walls_of_enclosures_031320.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Hadlos, A.; Opdyke, A.; Hadigheh, S.A. Where does local and indigenous knowledge in disaster risk reduction go from here? A systematic literature review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 79, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutzler, B.; Hudson, P.; Thieken, A.H. Adaptation strategies of flood-damaged businesses in Germany. Front. Water 2022, 4, 932061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Baynes, T.; McFallan, S.; West, J.; Khoo, Y.B.; Wang, X.; Quezada, G.; Mazouz, S.; Herr, A.; Beaty, R.M.; et al. Rising tides: Adaptation policy alternatives for coastal residential buildings in Australia. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2016, 12, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, P.; Mondino, E.; Borga, M.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Patt, A.; Scolobig, A. A flood-risk-oriented, dynamic protection motivation framework to explain risk reduction behaviours. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienzler, S.; Pech, I.; Kreibich, H.; Müller, M.; Thieken, A.H. After the extreme flood in 2002: Changes in preparedness, response and recovery of flood-affected residents in Germany between 2005 and 2011. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waggoner, J.W.; Olson, K.C. Feeding and Watering Beef Cattle During Disasters. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2018, 34, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwin, R. Evacuation of Pets During Disasters: A Public Health Intervention to Increase Resilience. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1413–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| COM-B Components | No-Regrets Criteria |

|---|---|

| Capability |

|

| Opportunity |

|

| Motivation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ommer, J.; Kalas, M.; Neumann, J.; Blackburn, S.; Cloke, H.L. A No-Regrets Framework for Sustainable Individual and Collective Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135828

Ommer J, Kalas M, Neumann J, Blackburn S, Cloke HL. A No-Regrets Framework for Sustainable Individual and Collective Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135828

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmmer, Joy, Milan Kalas, Jessica Neumann, Sophie Blackburn, and Hannah L. Cloke. 2025. "A No-Regrets Framework for Sustainable Individual and Collective Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135828

APA StyleOmmer, J., Kalas, M., Neumann, J., Blackburn, S., & Cloke, H. L. (2025). A No-Regrets Framework for Sustainable Individual and Collective Flood Preparedness Under Uncertainty. Sustainability, 17(13), 5828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135828