An Exploratory Estimation of the Willingness to Pay for and Perceptions of Nature-Based Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Nature-Based Therapy: Theory, Potential and Economic Evaluation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Administration

3.2. Survey Design and Structure

3.3. Scenario Description and Payment Vehicle

“Cardiac rehabilitation is usually offered in a hospital or clinic setting. Suppose that the nature-based rehabilitation is more costly than the clinic/hospital programme, as it is a new and innovative therapy offering, and that the extra costs would have to be paid for with your own money. Would you be willing to pay €X extra (out of your own pocket, in addition to any co-payment you may currently have to pay) per day to undertake the nature-based rehabilitation instead of the indoor clinic-based programme?”

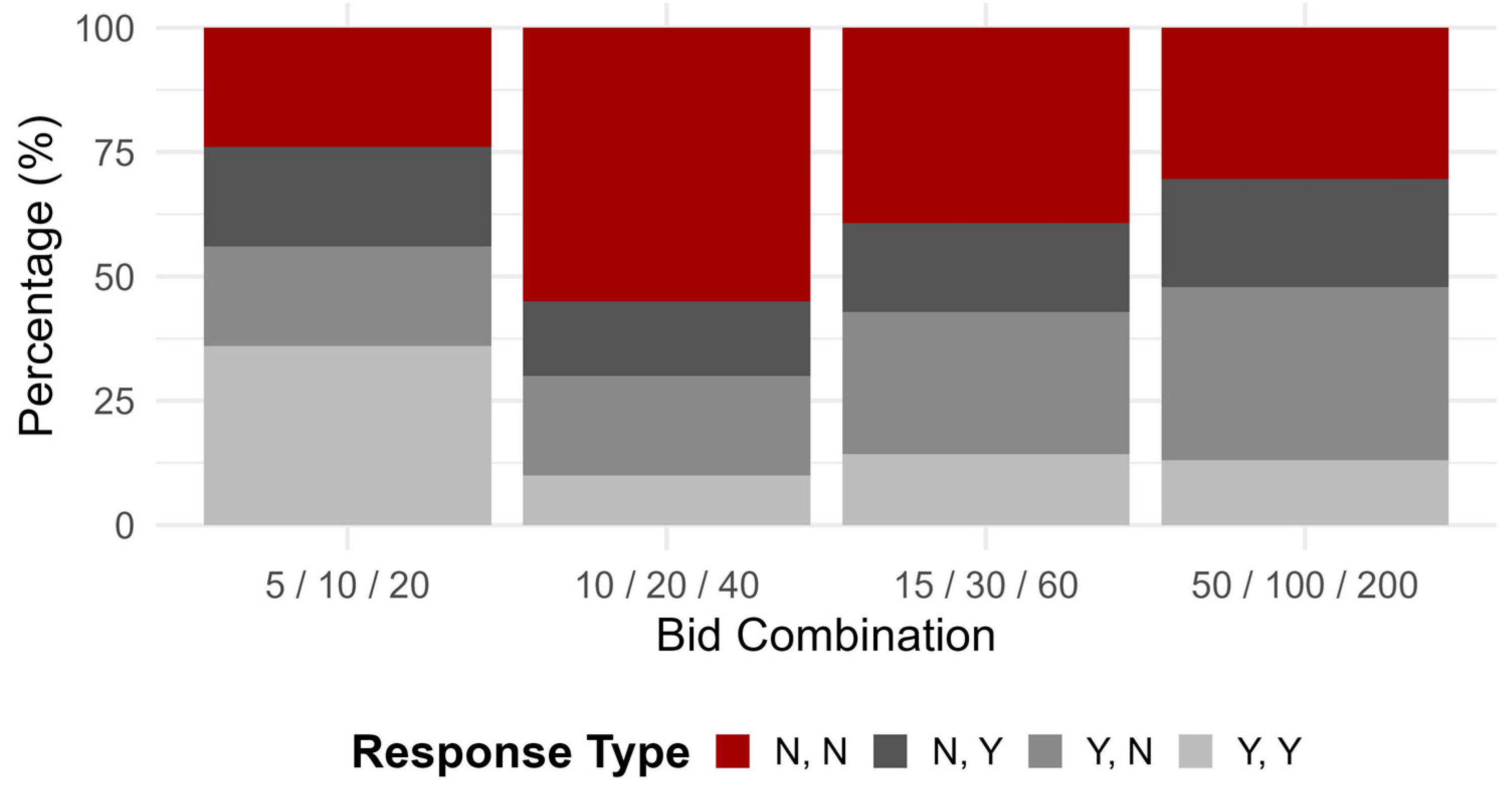

3.4. Elicitation of WTP

3.5. Empirical Strategy

3.6. Measures to Mitigate Risks of Potential Biases

3.7. Survey Implementation

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Descriptive Statistics

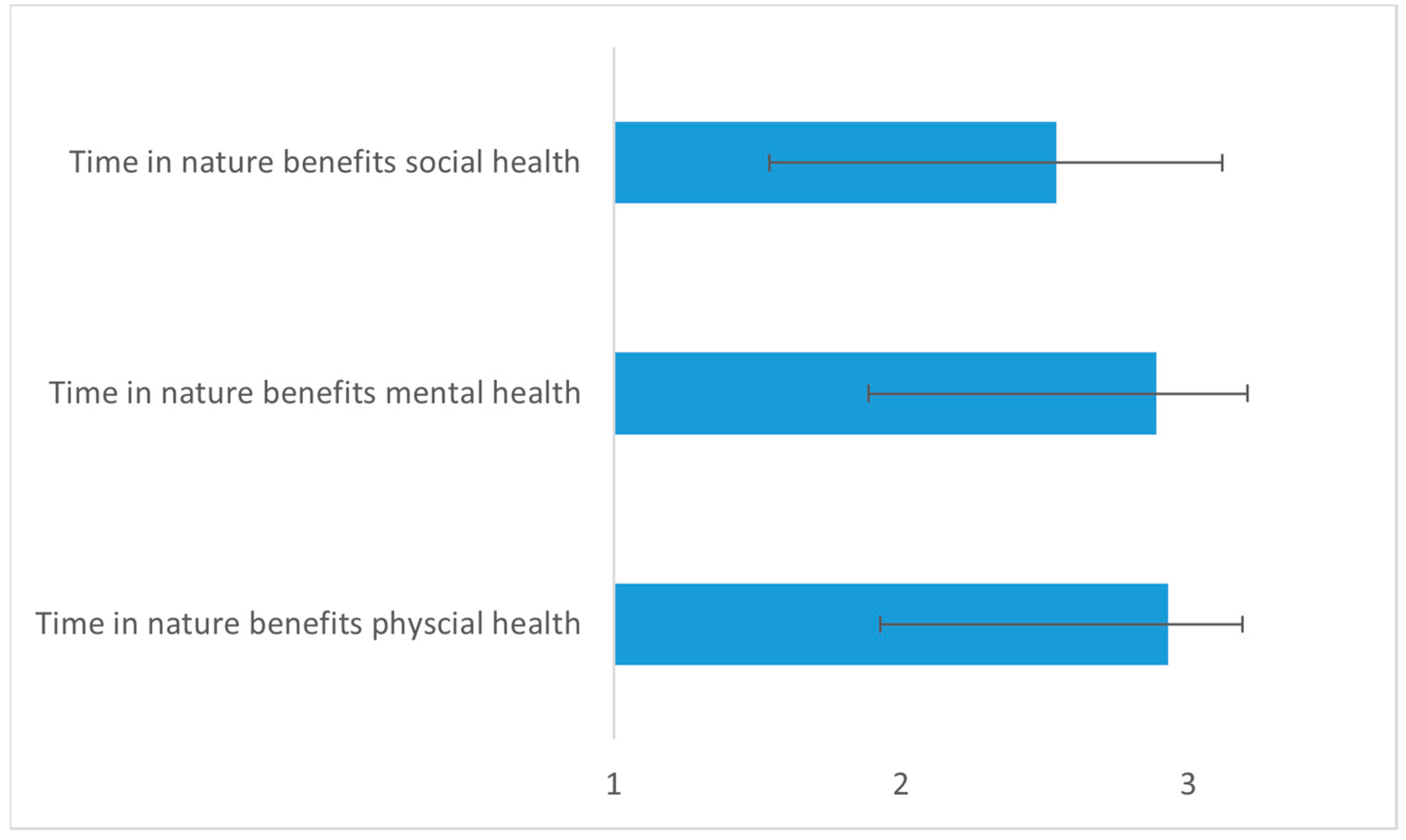

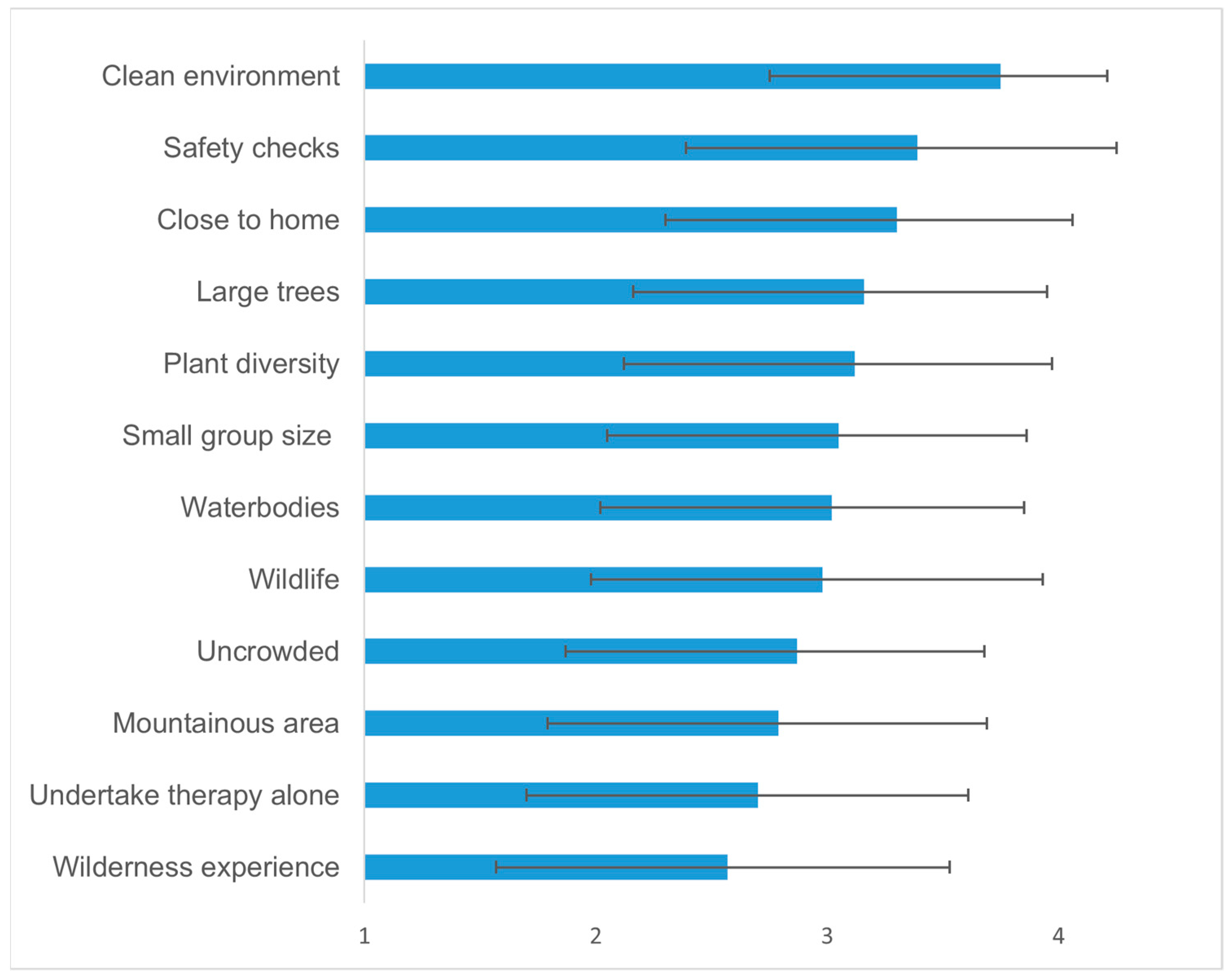

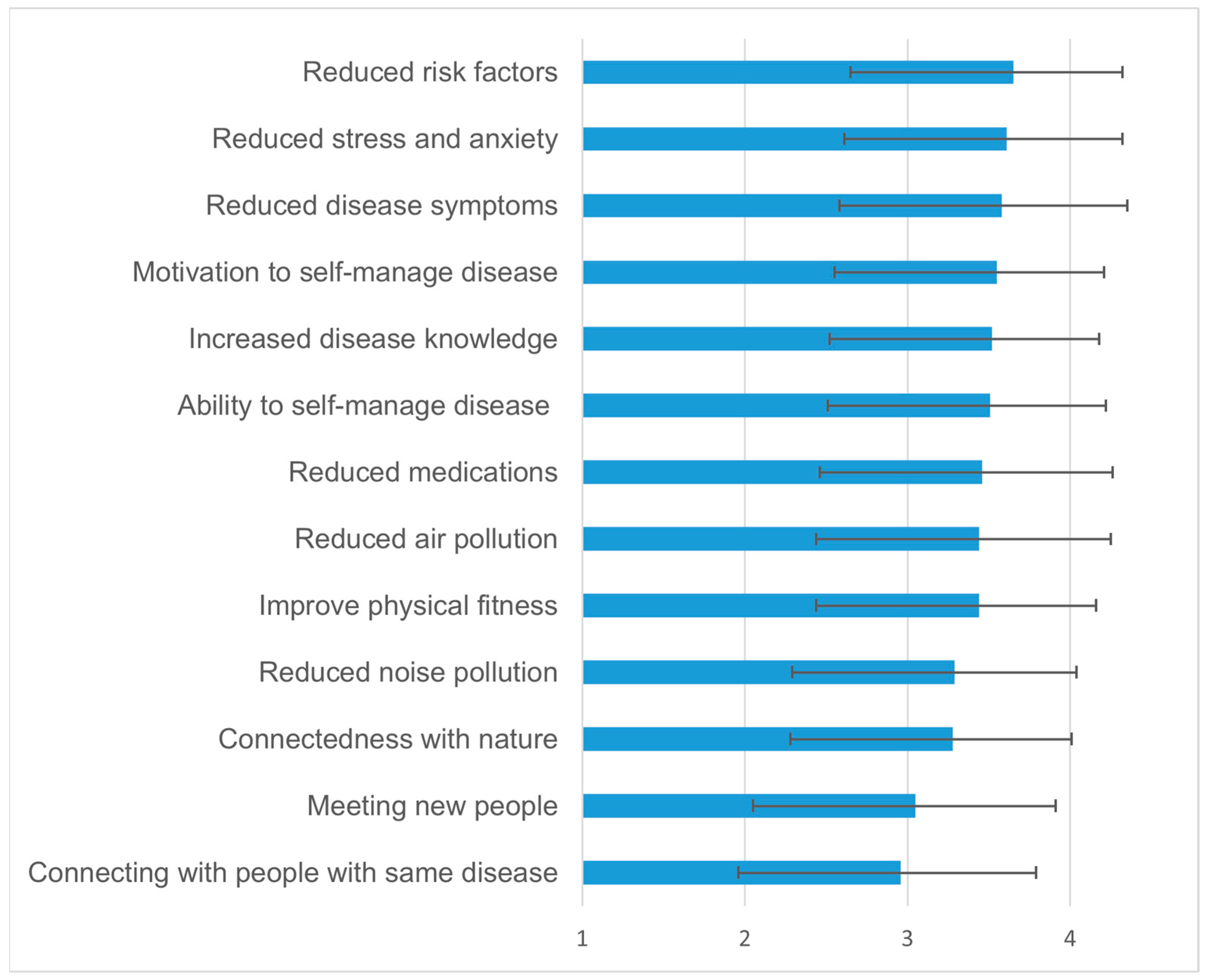

4.2. Knowledge, Perceptions and Preferences About Nature-Based Rehabilitation

4.3. Regression Results and WTP Estimates

5. Discussion

5.1. Knowledge, Perceptions and Preferences About Nature-Based Therapies

5.2. WTP for Nature-Based Therapy and Influencing Factors

5.3. Limitations of Our Study

5.4. Relevance for Policy and Management

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NBT | Nature-based therapy |

| NBI | Nature-based intervention |

| WTP | Willingness to pay |

| CV | Contingent valuation |

| DBDC | Double-bounded dichotomous choice |

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Mean (sd) | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences for features of NBT | |||

| Uncrowded | The area in which the outdoor programme takes place is sparsely crowded and you do not meet many people on the walking trails or in the exercise area | 2.87 (0.81) | 89 |

| Clean environment | The condition of the outdoor environment is clean, with no rubbish and trails are well maintained | 3.75 (0.46) | 91 |

| Small group size | The rehabilitation is also offered in a small group size of 5 people or less | 3.05 (0.81) | 84 |

| Undertake therapy alone | The rehabilitation is also offered to singular patients to undertake alone with the trained guides | 2.7 (0.91) | 80 |

| Safety checks | The area has been checked for environmental safety concerns such as snakes or poisonous plants, encounters are kept to a minimum | 3.39 (0.86) | 84 |

| Waterbodies | The presence of waterbodies visible in the outdoor exercise area and along the walking trails, such as rivers, lakes and waterfalls | 3.02 (0.83) | 88 |

| Wildlife | The chance to see birds, insects and small mammals along the walking trails | 2.98 (0.95) | 85 |

| Large trees | The presence of large tall trees | 3.16 (0.79) | 86 |

| Plant diversity | The presence of many different species of plants and trees in the outdoor exercise area and along the walking trails | 3.12 (0.85) | 83 |

| Mountainous area | The rehabilitation takes places in a mountainous area, where mountain ranges are visible in the surrounding areas | 2.79 (0.9) | 80 |

| Close to home | The location of the rehabilitation is close to my home and reachable within 1 h of driving | 3.3 (0.76) | 83 |

| Wilderness experience | The location of the rehabilitation is far from my home, and takes place in an area of uncontaminated nature with no signs of human development | 2.57 (0.96) | 69 |

| Importance of potential benefits | |||

| Improve physical fitness | Improvements in physical fitness | 3.44 (0.72) | 88 |

| Reduce disease symptoms | Reduction in symptoms of cardiovascular disease | 3.58 (0.77) | 81 |

| Reduce risk factors | Reduction in cardiovascular risk factors | 3.65 (0.67) | 84 |

| Reduce medications | Reduction in use of medications for cardiovascular disease | 3.46 (0.8) | 78 |

| Nature connectedness | Increased connectedness with nature | 3.28 (0.73) | 81 |

| Reduced air pollution | Reduced exposure to air pollution | 3.44 (0.81) | 84 |

| Reduced noise pollution | Reduced exposure to noise pollution | 3.29 (0.75) | 85 |

| Ability to manage disease | Increased ability to self-manage cardiovascular disease in future | 3.51 (0.71) | 82 |

| Increased disease knowledge | Increased knowledge on cardiovascular disease | 3.52 (0.66) | 79 |

| Less stress and anxiety | Reduced feelings of stress and anxiety | 3.61 (0.71) | 84 |

| Motivation to manage disease | Increased motivation to actively self-manage cardiovascular disease | 3.55 (0.66) | 78 |

| Meeting new people | Meeting new people increasing social connections | 3.05 (0.86) | 82 |

| Connecting with people with disease | Connecting with other people with cardiovascular disease | 2.96 (0–83) | 80 |

Appendix C

| Reasons | % |

|---|---|

| Positive WTP respondents | |

| True positive WTP | |

| I believe it will provide better results in terms of my health compared to the other | 18% |

| I would like to try this new type of rehabilitation | 33% |

| I believe it can help the environment to be more valued and therefore protected | 6% |

| Other | 1% |

| Invalid positive WTP | |

| I answered randomly | 1% |

| I did not understand the WTP question | 1% |

| Non-WTP respondents | |

| True non-WTP | |

| The amount was too high for the therapy | 0 |

| The amount was too high for my budget | 9% |

| I am not interested in outdoor cardiac rehabilitation | 2% |

| I think that conventional indoor rehabilitation is already good enough and does not need to be undertaken outdoors | 1% |

| Protest response non-WTP | |

| I don’t think that it is realistic to undertake this therapy | 0 |

| I need more information before taking a decision | 3% |

| I do not think I need to undertake a COPD rehabilitation | 2% |

| The government or insurance companies should pay for the rehabilitation and not patients | 12% |

| I do not think nature-based rehabilitation can be effective | 2% |

References

- Dye, C. Health and Urban Living. Science 2008, 319, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louv, R. The Nature Principle: Human Restoration and the End of Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 1616200758. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, R.; Julien, M. Urbanisation and Health. Clin. Med. 2005, 5, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease 2021: Findings from the GBD 2021 Study; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Vos, T.; Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Flaxman, A.D.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S. Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) for 291 Diseases and Injuries in 21 Regions, 1990–2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2197–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cafiero, E.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Bloom, L.R.; Fathima, S.; Feigl, A.B.; Gaziano, T.; Hamandi, A.; Mowafi, M. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases; Program on the Global Demography of Aging: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J. Nature-Based Interventions and Mind–Body Interventions: Saving Public Health Costs Whilst Increasing Life Satisfaction and Happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marselle, M.R.; Hartig, T.; Cox, D.T.C.; de Bell, S.; Knapp, S.; Lindley, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K.; Braubach, M.; Cook, P.A.; et al. Pathways Linking Biodiversity to Human Health: A Conceptual Framework. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Hartig, T.; Martin, L.; Pahl, S.; van den Berg, A.E.; Wells, N.M.; Costongs, C.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Elliott, L.R.; Godfrey, A.; et al. Nature-Based Biopsychosocial Resilience: An Integrative Theoretical Framework for Research on Nature and Health. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Peacock, J.; Hine, R.; Sellens, M.; South, N.; Griffin, M. Green Exercise in the UK Countryside: Effects on Health and Psychological Well-Being, and Implications for Policy and Planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2007, 50, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Navakatikyan, M.A.; Feng, X. Contact with Nature May Be a Remedy for Loneliness: A Nationally Representative Longitudinal Cohort Study. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, S.; Bojke, L.; Coventry, P. The Cost Effectiveness of Ecotherapy as a Healthcare Intervention, Separating the Wood from the Trees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Astell–burt, T.; Barber, E.A.; Brymer, E.; Cox, D.T.C.; Dean, J.; Depledge, M.; Fuller, R.A.; Hartig, T.; Irvine, K.N.; et al. Nature–Based Interventions for Improving Health and Wellbeing: The Purpose, the People and the Outcomes. Sports 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosedale, J.; Hartl, A.; Pichler, C.; Bischof, M. Alpine Assets, Perceptions and Strategies for Nature-Based Health Tourism. In Digital and Strategic Innovation for Alpine Health Tourism: Natural Resources, Digital Tools and Innovation Practices from HEALPS 2 Project; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mughal, R.; Seers, H.; Polley, M.; Sabey, A.; Chatterjee, H.J. How the Natural Environment Can Support Health and Wellbeing Through Social Prescribing; NASP: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- BC Parks Foundation PaRx: A Prescription for Nature—About. Available online: https://www.parkprescriptions.ca/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.-J.; Miyazaki, Y. Trends in Research Related to “Shinrin-Yoku”(Taking in the Forest Atmosphere or Forest Bathing) in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y.; Kim, E.; Paek, D. Evidence-Based Status of Forest Healing Program in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikomeye, J.C.; Balza, J.S.; Kwarteng, J.L.; Beyer, A.M.; Beyer, K.M.M. The Impact of Greenspace or Nature-Based Interventions on Cardiovascular Health or Cancer-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struthers, N.A.; Guluzade, N.A.; Zecevic, A.A.; Walton, D.M.; Gunz, A. Nature-Based Interventions for Physical Health Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busk, H.; Sidenius, U.; Kongstad, L.P.; Corazon, S.S.; Petersen, C.B.; Poulsen, D.V.; Nyed, P.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Economic Evaluation of Nature-Based Therapy Interventions—A Scoping Review. Challenges 2022, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Monetary Valuation of Urban Nature’s Health Effects: A Systematic Review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; García, J.; Wendling, L. Linkages between the Concept of Nature-Based Solutions and the Notion of Landscape. Ambio 2024, 53, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA-JRC. Environment and Human Health; EEA-JRC: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013; Volume 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sola Corazon, S.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Grete Claudi Jensen, A.; Nilsson, K. Development of the Nature-Based Therapy Concept for Patients with Stress-Related Illness at the Danish Healing Forest Garden Nacadia. J. Ther. Hortic. 2010, 20, 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Annerstedt, M.; Währborg, P. Nature-Assisted Therapy: Systematic Review of Controlled and Observational Studies. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smock, C.R.; Schultz, C.L.; Gustat, J.; Layton, R.; Slater, S.J. Perceptions of Knowledge and Experience in Nature-Based Health Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986; ISBN 0674268393. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989; ISBN 0521349397. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at Least 120 Minutes a Week in Nature Is Associated with Good Health and Wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, E.P.; Freeman, P.; Gladwell, V.F. A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Predictors of Visit Frequency to Local Green Space and the Impact This Has on Physical Activity Levels. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, E.W.; Lombard, Q.K.; Best, N.; Smiley-Smith, S.; Quinn, J.E. Active and Passive Use of Green Space, Health, and Well-Being amongst University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, M.; Einwanger, J.; Hartl, A.; Kopp, M. Affective Responses in Mountain Hiking—A Randomized Crossover Trial Focusing on Differences between Indoor and Outdoor Activity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e177719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Park, S.-A.; Mjelde, J.W.; Cho, J.-H. Measuring the Willingness-to-Pay for a Horticulture Therapy Site Using a Contingent Valuation Method. Hortscience 2008, 43, 1802–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartfiel, N.; Gittins, H.; Morrison, V.; Wynne-Jones, S.; Dandy, N.; Edwards, R.T. Social Return on Investment of Nature-Based Activities for Adults with Mental Wellbeing Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, K.; Crabtree, B.; Osman, L.M.; Cathrine, K. Green Space and Health Benefits: A QALY and CEA of a Mental Health Programme. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.C.; Carson, R.T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; ISBN 1315060566. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, P.A.; Hausman, J.A. Contingent Valuation: Is Some Number Better than No Number? J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, J.F.; Shin, S.Y.; Hayes, D.J.; Kliebenstein, J.B. Resolving Differences in Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, R.T.; Hanemann, W.M. Chapter 17 Contingent Valuation. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 821–936. ISBN 9780444511454. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.D. Contingent Valuation in Health Care: Does It Matter How the “good” Is Described? Health Econ. 2008, 17, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LimeSurvey GmbH. LimeSurvey: An Open-Source Survey Tool. Available online: http://www.limesurvey.org (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Arrow, K.; Solow, R.; Portney, P.R.; Leamer, E.E.; Radner, R.; Schuman, H. Report of the NOAA Panel on Contingent Valuation. Fed. Regist. 1993, 58, 4601–4614. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhjem, H.; Navrud, S. Are Internet Surveys an Alternative to Face-to-Face Interviews in Contingent Valuation? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.S. Use of the Internet for Willingness-to-Pay Surveys. A Comparison of Face-to-Face and Web-Based Interviews. Resour. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Mentzakis, E.; Matheson, C.; Bond, C. Survey Modes Comparison in Contingent Valuation: Internet Panels and Mail Surveys. Health Econ. 2020, 29, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Vic Adamowicz, W.; Bennett, J.; Brouwer, R.; Ann Cameron, T.; Michael Hanemann, W.; Hanley, N.; Ryan, M.; Scarpa, R.; et al. Contemporary Guidance for Stated Preference Studies. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 4, 319–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigenberger, C.; Flatscher-Thoeni, M.; Siebert, U.; Leiter, A.M. Determinants of Willingness to Pay for Health Services: A Systematic Review of Contingent Valuation Studies. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 1455–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gail, K.; Uyan, V. Estimation of Tourists’ Willingness to Pay Entrance Fees for a Forest Bathing Site in the Philippines. J. Manag. Dev. Stud. 2020, 9, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Herens, M.C.; van Ophem, J.A.C.; Wagemakers, A.M.A.E.; Koelen, M.A. Predictors of Willingness to Pay for Physical Activity of Socially Vulnerable Groups in Community-Based Programs. Springerplus 2015, 4, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, W.M. Valuing the Environment through Contingent Valuation. J. Econ. Perspect. 1994, 8, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, R. Willingness to Pay Methods in Health Care: A Sceptical View. Health Econ. 2003, 12, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldsont, C.; Farrart, S.; Mapp, T.; Walker, A.; Macphee, S. Assessing Community Values in Health Care: Is The “Willingness To Pay” Method Feasible? Health Care Anal. 1997, 5, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, M.; Loomis, J.; Kanninen, B. Statistical Efficiency of Double-Bounded Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1991, 73, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, I.J.; Burgess, D.; Hutchinson, W.G.; Matthews, D.I. Learning Design Contingent Valuation (LDCV): NOAA Guidelines, Preference Learning and Coherent Arbitrariness. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior. In Fontiers in Econometrics; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2024.

- Aizaki, H.; Nakatani, T.; Sato, K.; Fogarty, J. R Package DCchoice for Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation: A Contribution to Open Scientific Software and Its Impact. Jpn. J. Stat. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, J.; Hu, W. Cheap Talk Efficacy under Potential and Actual Hypothetical Bias: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 96, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, I.J.; Day, B.H.; Jones, A.P.; Jude, S. Reducing Gain–Loss Asymmetry: A Virtual Reality Choice Experiment Valuing Land Use Change. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2009, 58, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajita, M.I.; Denhaerynck, K.; Dobbels, F.; Berben, L.; Russell, C.L.; Davidson, P.M.; De Geest, S. Health Literacy in Heart Transplantation: Prevalence, Correlates and Associations with Health Behaviors—Findings from the International BRIGHT Study. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2017, 36, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, P.A.; Brown, J.V.E.; Pervin, J.; Brabyn, S.; Pateman, R.; Breedvelt, J.; Gilbody, S.; Stancliffe, R.; McEachan, R.; White, P.C.L. Nature-Based Outdoor Activities for Mental and Physical Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; Galvão, A.L.d.S.; Loureiro, A.I.S.; Ferreira, M.E.G.; Monstans, M.C.; Medeiros, L.C.d.C. Valuing Urban Green Spaces for Enhanced Public Health and Sustainability: A Study on Public Willingness-to-Pay in an Emerging Economy. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2024, 98, 128386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodev, Y.; Zhiyanski, M.; Glushkova, M.; Borisova, B.; Semerdzhieva, L.; Ihtimanski, I.; Dimitrov, S.; Nedkov, S.; Nikolova, M.; Shin, W.S. An Integrated Approach to Assess the Potential of Forest Areas for Therapy Services. Land 2021, 10, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Kruger, L.E.; Schultz, C.L.; Henderson, J.R. Key Characteristics of Forest Therapy Trails: A Guided, Integrative Approach. Forests 2023, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Veneto Nomenclatore Tariffario Prestazioni Specialistiche Ambulatoriali. Available online: https://bur.regione.veneto.it/BurvServices/Pubblica/Download.aspx?name=61_allegato_178934.pdf&type=9&storico=False (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Burge, A.T.; Holland, A.E.; McDonald, C.F.; Hill, C.J.; Lee, A.L.; Cox, N.S.; Moore, R.; Nicolson, C.; O’Halloran, P.; Lahhama, A.; et al. “Willingness to Pay”: The Value Attributed to Program Location by Pulmonary Rehabilitation Participants. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 18, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somta, S.; Völker, M.; Widyastari, D.A.; Mysook, S.; Wongsingha, N.; Potharin, D.; Katewongsa, P. Willingness-to-Pay in Physical Activity: How Much Older Adults Value the Community-Wide Initiatives Programs? Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1282877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglietto, A.; Manfredi, R.; Elia, E.; D’Ascenzo, F.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Munzel, T. Cardiovascular Disease Burden. Italian and Global Perspectives. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2021, 69, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, R.; Groot, W.; Pavlova, M. Preferences for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Care: A Discrete Choice Experiment among Patients in Lebanon. Clin. Rehabil. 2023, 37, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberini, A. Optimal Designs for Discrete Choice Contingent Valuation Surveys: Single-Bound, Double-Bound, and Bivariate Models. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1995, 28, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanninen, B.J. Bias in Discrete Response Contingent Valuation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1995, 28, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; De Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green Space, Urbanity, and Health: How Strong Is the Relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indoor Clinic-Based Rehabilitation | Outdoor Nature-Based Rehabilitation | |

|---|---|---|

| Activities: | Description: | |

| Aerobic exercise | Walking on a treadmill in a training room | Guided walks outdoors in nature |

| Guided strength training | In a training room using resistance bands and gym machines | Outdoors in nature in a suitably chosen exercise space in areas such as parks, forests or mountainous areas using resistance bands and body weight |

| Guided relaxation exercises | In a training room | Outdoors in a suitably chosen exercise space |

| Guided balance and flexibility exercises | In a training room | Outdoors in a suitably chosen exercise space |

| Programme aim: | ||

| To reduce disease symptoms and return patients back to the best level of independent functioning possible post heart transplant or exacerbation (similar to standard cardiac rehabilitation). | To reduce disease symptoms and return patients back to the best level of independent functioning possible post heart transplant or exacerbation while taking advantage of the benefits of physical exercise and direct contact with nature. To encourage and give patients the skills and knowledge to continue with exercises outdoors once the programme ends. |

| Answer to Initial Bid (A1) | Answer to Follow-Up Bid | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Yes | WTPi > A2 | A1< WTPi < A2 |

| No | A1 > WTPi >A3 | WTPi < A3 |

| Characteristic | Level | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–29 | 3 (3.06) |

| 30–39 | 7 (7.14) | |

| 40–49 | 5 (5.10) | |

| 50–59 | 21 (21.43) | |

| 60–69 | 27 (27.55) | |

| Over 70 | 33 (33.67) | |

| No answer | 2 (2.04) | |

| Gender | Female | 29 (29.59) |

| Male | 69 (70.41) | |

| Education | Primary school | 6 (6.12) |

| Middle school | 27 (27.55) | |

| High school | 49 (50.00) | |

| Bachelor degree | 3 (3.06) | |

| Master degree | 11 (11.22) | |

| Specialised post master degree | 2 (2.04) | |

| Monthly income | Less than EUR 600 | 6 (6.12) |

| Between EUR 600 and EUR 1249 | 25 (25.51) | |

| Between EUR 1250 and EUR 1669 | 16 (16.33) | |

| Between EUR 1670 and EUR 2499 | 13 (13.27) | |

| Between EUR 2500 and EUR 3339 | 1 (1.02) | |

| Between EUR 3340 and EUR 4169 | 4 (4.08) | |

| Between EUR 4170 and EUR 4999 | 4 (4.08) | |

| Between EUR 5000 and EUR 5839 | 2 (2.04) | |

| Between EUR 5840 and EUR 7500 | 2 (2.04) | |

| Above EUR 7500 | 4 (4.08) | |

| No answer | 21 (21.43) | |

| Level of cardiovascular disease | At risk but no symptoms | 60 (61.22) |

| Structural heart disease but no symptoms | 13 (13.27) | |

| Current or previous symptoms of heart failure | 4 (4.08) | |

| Don’t know/unspecified | 21 (21.43) | |

| Participated in past cardiac rehabilitation | Yes | 44 (44.89) |

| Perceived need for rehabilitation | Very unlikely | 23 (23.47) |

| Unlikely | 35 (35.71) | |

| Likely | 34 (34.69) | |

| Very likely | 6 (6.12) |

| Statements Evaluated on a 5-Point Likert Scale | Mean (sd) |

|---|---|

| Outdoor exercise should be utilised for cardiovascular disease | 4.40 (0.68) |

| NBT can be dangerous for cardiovascular disease | 2.14 (1.3) |

| NBT is backed up by enough science | 3.57 (0.99) |

| NBT should be paid for by the State | 3.82 (1.15) |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 0.509 | |

| (0.450) | ||

| Age 30–39 | 1.156 | |

| (1.526) | ||

| Age 40–49 | 0.137 | |

| (1.688) | ||

| Age 50–59 | −0.658 | |

| (1.430) | ||

| Age 60–69 | 0.427 | |

| (1.436) | ||

| Age > 70 | −0.281 | |

| (1.390) | ||

| High-school education | 0.690 | |

| (0.468) | ||

| University degree | 1.692 ** | |

| (0.661) | ||

| Chose NBT | 1.589 *** | |

| (0.582) | ||

| Good knowledge of NBT | 1.128 ** | |

| (0.542) | ||

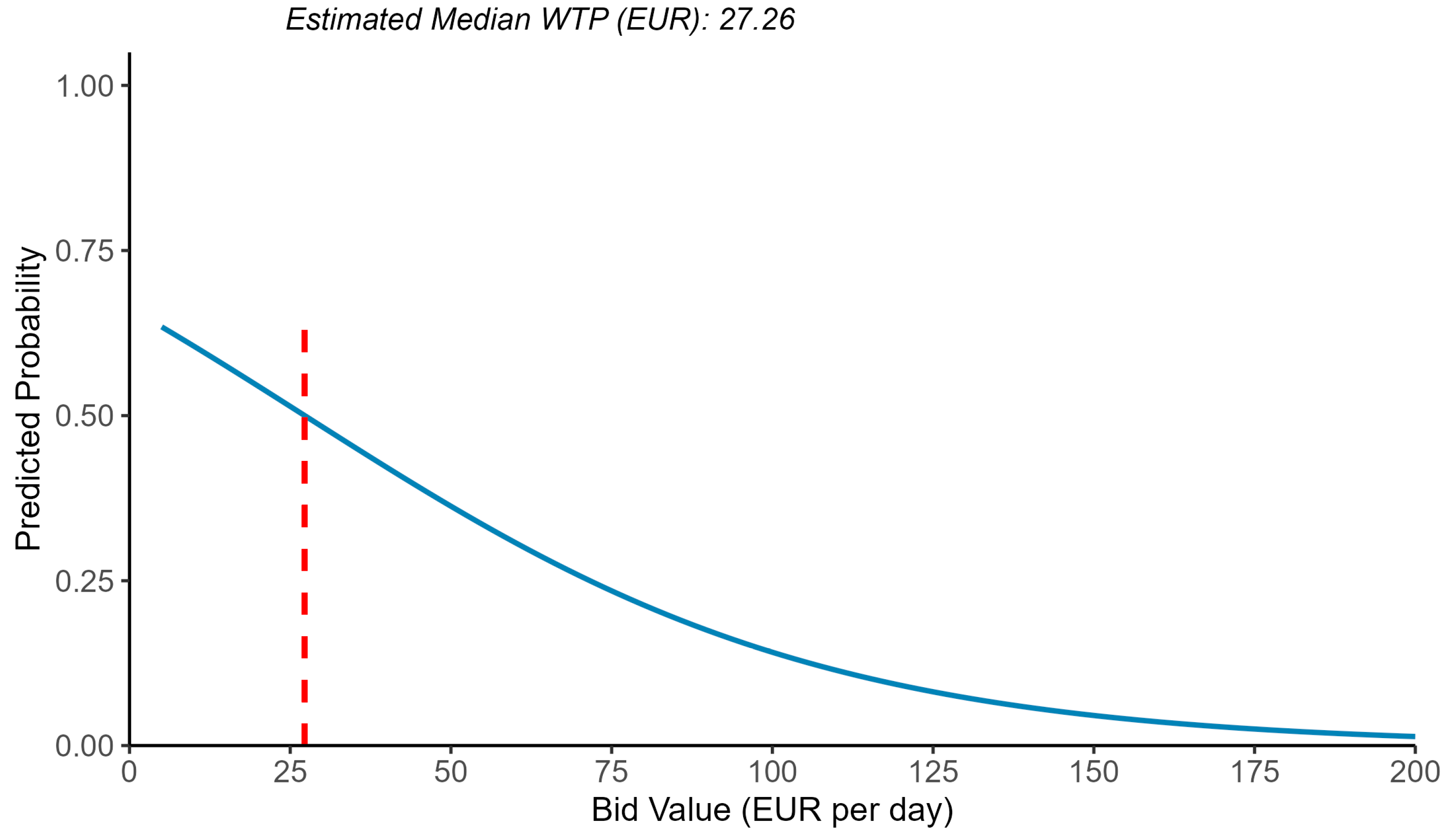

| Bid | −0.025 *** | −0.030 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Constant | 0.675 *** | −1.613 |

| (0.212) | (1.472) | |

| Log-likelihood | −151.957 | −137.323 |

| Likelihood ratio (LR) statistic | 0 | 29.269 |

| Degrees of freedom | 0 | 10 |

| p value | 1 | 0.001 |

| AIC | 307.915 | 298.646 |

| BIC | 313.044 | 329.165 |

| Observations | 96 | 94 |

| Median WTP | 27.26 | 28.81 |

| 95% CI | EUR 14.01–EUR 42.69 | EUR 6.80–EUR 48.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sealy Phelan, A.; Pisani, E.; Tessari, C.; Secco, L. An Exploratory Estimation of the Willingness to Pay for and Perceptions of Nature-Based Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135779

Sealy Phelan A, Pisani E, Tessari C, Secco L. An Exploratory Estimation of the Willingness to Pay for and Perceptions of Nature-Based Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135779

Chicago/Turabian StyleSealy Phelan, Aisling, Elena Pisani, Chiara Tessari, and Laura Secco. 2025. "An Exploratory Estimation of the Willingness to Pay for and Perceptions of Nature-Based Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135779

APA StyleSealy Phelan, A., Pisani, E., Tessari, C., & Secco, L. (2025). An Exploratory Estimation of the Willingness to Pay for and Perceptions of Nature-Based Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases. Sustainability, 17(13), 5779. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135779