Assessing Walkability in Riyadh’s Commercial Streets: Public Perceptions and Prioritization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Assess public perceptions of walkability indicators in Riyadh’s commercial streets;

- Identify key walkability gaps based on importance and satisfaction measures;

- Propose evidence-based, context-specific urban design improvements.

“How do residents of Riyadh perceive walkability in commercial streets, and which indicators represent the greatest gap between importance and satisfaction in a car-oriented urban environment?”

2. Background

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection Procedure for Questionnaire

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

- W is the weight given to each indicator by respondents (ranging from 1 to 5);

- A is the highest possible weight (i.e., 5);

- N is the total number of respondents.

4. Analysis

4.1. Quantitative Findings

4.2. Gap/Disgruntlement Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Individual Characteristics

5.2. Travel Behaviour

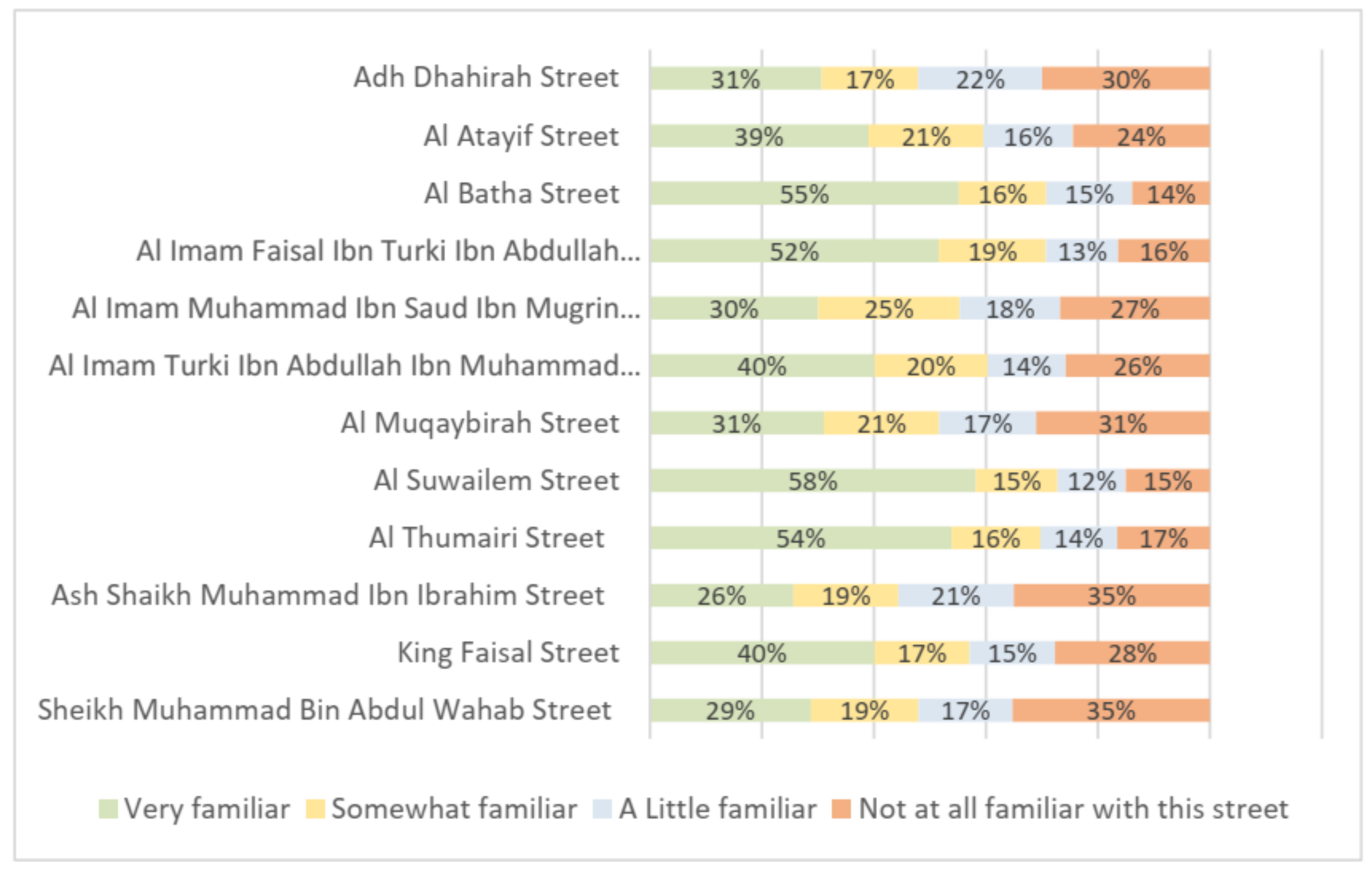

5.2.1. Familiarity with Commercial Streets in Riyadh’s Central Area

5.2.2. Perceptions of Walkability in the Ad-Dirah District

5.2.3. Frequency of Use of Transportation Modes

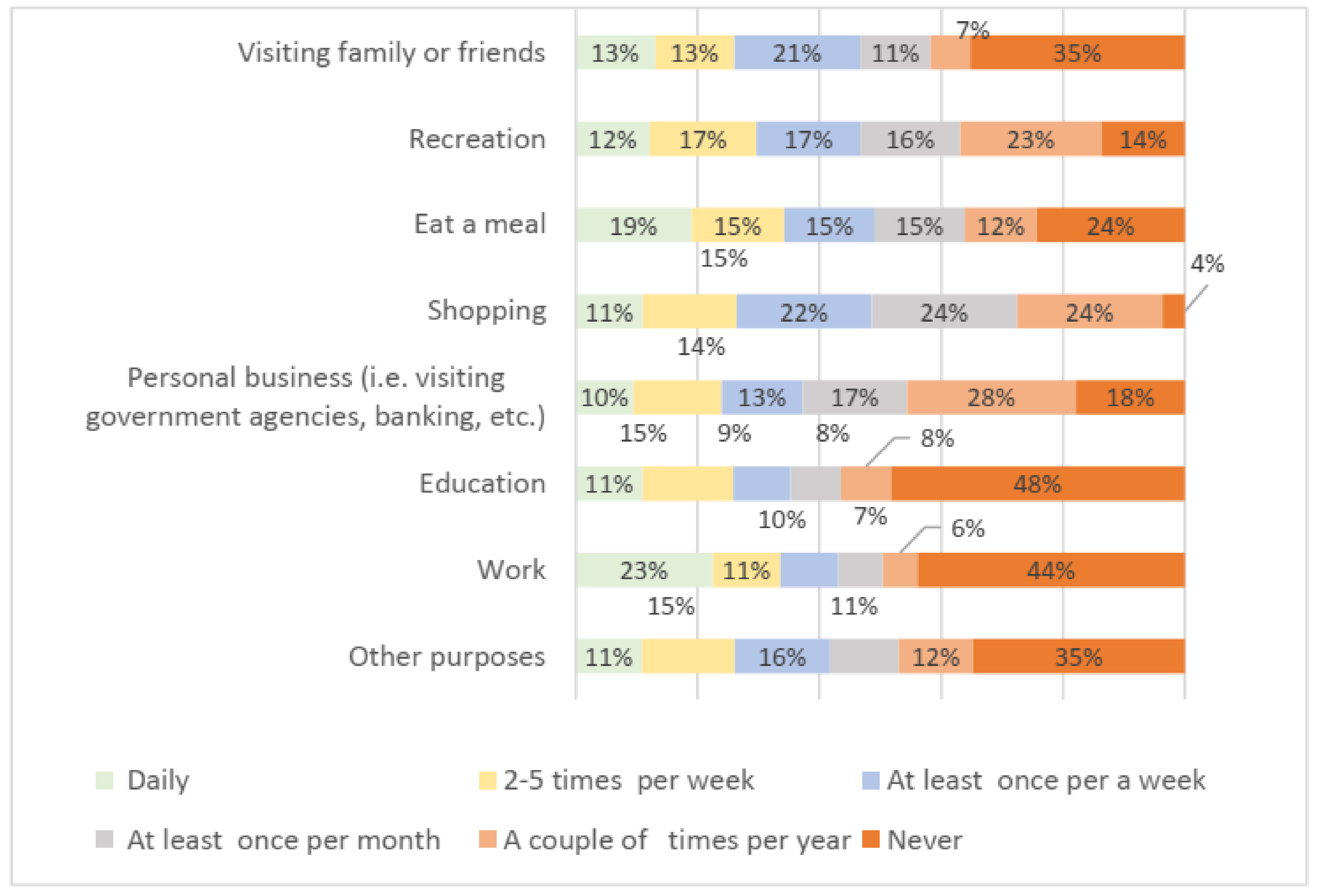

5.2.4. Potential Purposes for Walking in Riyadh’s Central Area

5.2.5. Acceptable Walking Distances

5.2.6. Impact of COVID-19

5.3. Perceptions of Walking in Riyadh Compared to Non-GCC Cities

5.4. Levels of Importance and Satisfaction

5.4.1. Cultural Features

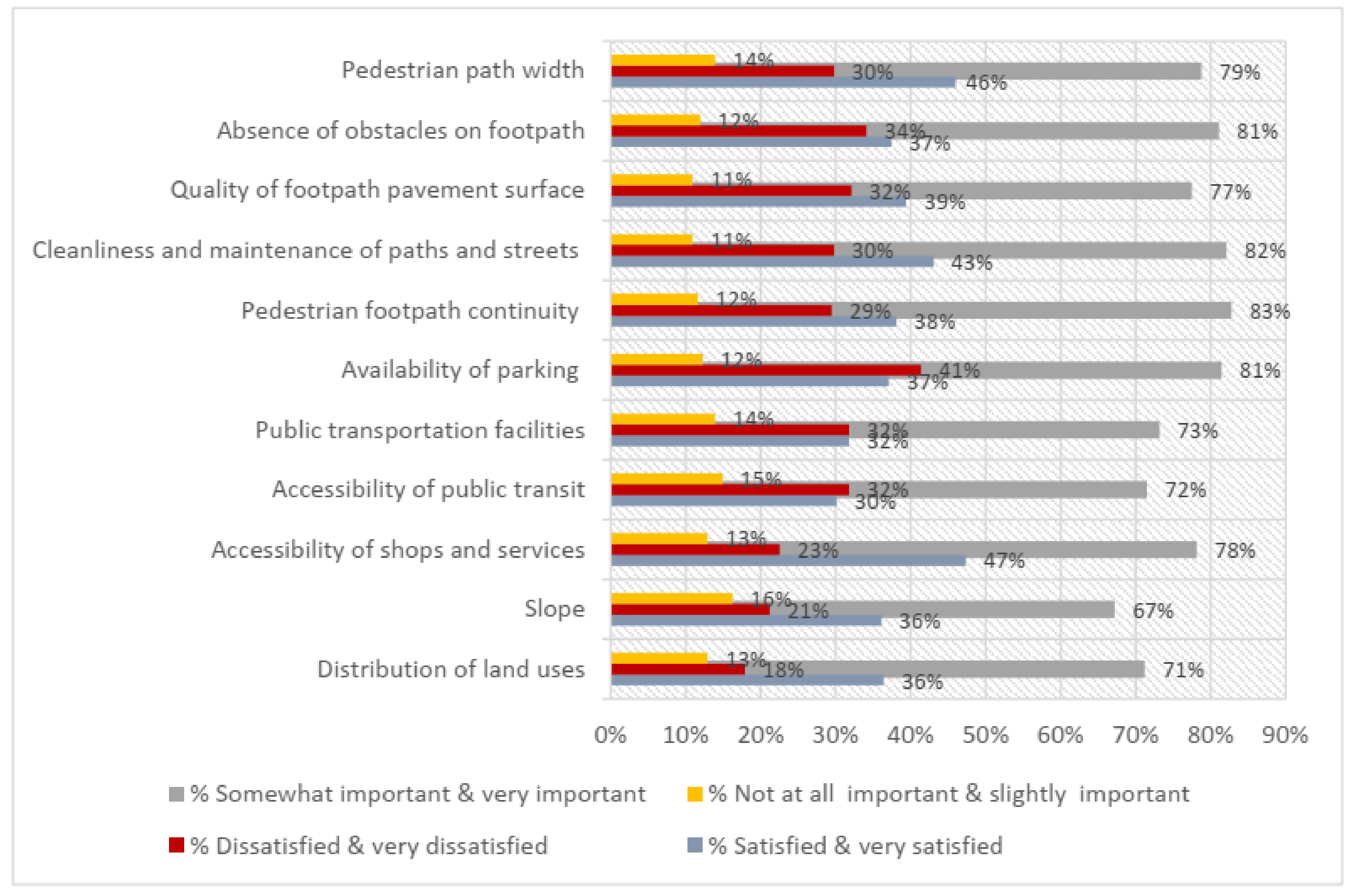

5.4.2. Functional Features

5.4.3. Safety Features

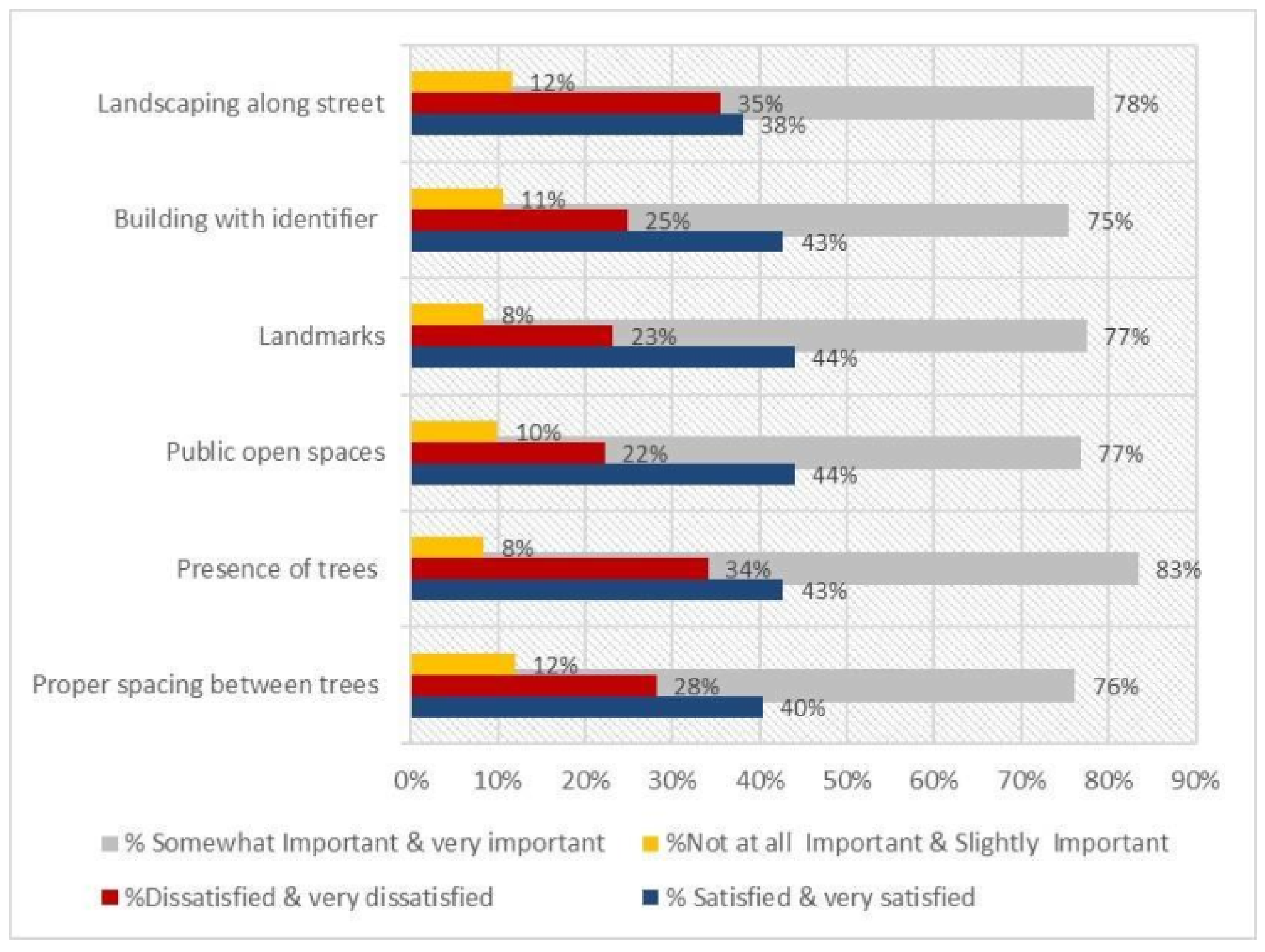

5.4.4. Aesthetic Qualities

5.4.5. Comfort Features

5.5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frank, L.; Sallis, J.; Conway, T.; Chapman, J.; Saelens, B.; Bachman, W. Many pathways from land use to health: Associations between neighborhood walkability and active transportation, body mass index, and air quality. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. Principles and criteria for assessing urban energy resilience: A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1654–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Katar, I.; Al-Atroush, M. Towards sustainable pedestrian mobility in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia: A case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahdy, O. Making a Hot, Arid, Desert Arab City More Livable: Investigating the Role of Street Design in Enhancing Walkability in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alawadi, K.; Hernandez Striedinger, V.; Maghelal, P.; Khanal, A. Assessing walkability in hot arid regions: The case of downtown Abu Dhabi. Urban Des. Int. 2021, 27, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030. Def. J. 2016, 19, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Alyami, S. Opportunities and challenges of embracing green city principles in saudi arabia future cities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 178584–178595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, N.; Burke, M. What are the most important factors for pedestrian level-of-service estimation? A systematic review of the literature. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Newman, P.; Takao, Y. Sustainable development goals: How can Japanese local governments help. In Proceedings of the 4th World Sustainability Forum, Virtual Event, 1–30 November 2014; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Homoud, M.; Jarrar, O. Walkability in Riyadh: A comprehensive assessment and implications for sustainable community—Al-Falah case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabiri, S.; Pourjafar, M.; Izadi, M. A case study of walkability and neighborhood attachment. Glob. J. Hum.-Soc. Sci. 2020, 20, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, F.; Zakaria, R.; Bigah, Y.; Mustafar, M.; Puan, O.; Zin, I.; Klufallah, M. Conceptualising the indicators of walkability for sustainable transportation. J. Teknol. 2013, 65, 2180–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Joh, K.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Park, H.; Woo, A. Assessing benefits of neighborhood walkability to single-family property values: A spatial hedonic study in Austin, Texas. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2015, 35, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Hart, J.; Laden, F. Neighborhood walkability and particulate air pollution in a nationwide cohort of women. Environ. Res. 2015, 142, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankey, S.; Marshall, J.; Brauer, M. Health impacts of the built environment: Within-urban variability in physical inactivity, air pollution, and ischemic heart disease mortality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C. “The 15-Minute City”: Redesigning urban life with proximity to services. Barc. Soc. J. Soc. Knowl. Anal. 2024, 30, hal-04648637. [Google Scholar]

- Atef Elhamy Kamel, M. Encouraging walkability in GCC cities: Smart urban solutions. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2013, 2, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, X.; Xiao, Z. Impact of Built Environment on Carbon Emissions from Cross-District Mobility: A Social Network Analysis Based on Private Vehicle Trajectory Big Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, O.; Al-Homoud, M. Sustainable urban development in Riyadh: A projected model for walkability. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2024, 16, 398–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Meyer-Habighorst, C.; Humpe, A. A global review of marine air pollution policies, their scope and effectiveness. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Why cities need to take road space from cars-and how this could be done. J. Urban Des. 2020, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselwander, M.; Weiss, D.; Werland, S. Local super apps in the 15-minute city: A new model for sustainable smart cities? Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1404105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzig, F.; Mühlhoff, R.; Römer, J. Decarbonizing urban transport in European cities: Four cases show possibly high co-benefits. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 044042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, S. Neo-growth in future post-carbon cities. J. Futur. Stud. 2013, 18, 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu, M.; Morefield, P.; Bierwagen, B.; Weaver, C. Urban adaptation can roll back warming of emerging megapolitan regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2909–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southworth, M. Designing the walkable city. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2005, 131, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, J.; Kim, H. Neighborhood walkability and active transportation: A correlation study in leisure and shopping purposes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. “Does compact development make people drive less?” The answer is yes. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-hagla, K. Sustainable urban development in historical areas using the tourist trail approach: A case study of the Cultural Heritage and Urban Development (CHUD) project in Saida, Lebanon. Cities 2010, 27, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Evaluating Transportation Equity; Victoria Transport Policy Institute: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, M.; Scholz, W. Towards sustainable urban development: Challenges and chances of climate-sensitive urban design in Muscat/Oman. Sustain. Gulf 2017, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Dumbaugh, E. The built environment and traffic safety: A review of empirical evidence. J. Plan. Lit. 2009, 23, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljoufie, M.; Zuidgeest, M.; Brussel, M.; Maarseveen, M. Spatial–temporal analysis of urban growth and transportation in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Cities 2013, 31, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatar, K.; Almulhim, A. The Issue of Urban Transport Planning in Saudi Arabia: Concepts and Future Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Sulaiman, F. Striding towards sustainable urban livability: Evaluating walkability efficiency vis-a-vis population dynamics in Saudi Arabia cities. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2340428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloshan, M.; Gharieb, M.; Heba, K.; Khalil, R.; Alhumaid, M.; Ezz, M. Promoting Urban Corridors in Saudi City Center to Enhance Walkability Using Multi-Criteria Decision-Analysis Methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Golub, A. Evaluating the Distributional Effects of Regional Transportation Plans and Projects; Portland State University, National Institute for Transportation: Portland, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Golub, A.; Martens, K. Using principles of justice to assess the modal equity of regional transportation plans. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the unmeasurable: Urban design qualities related to walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkrides, B. Promoting Sustainable Urban Walkability: A Modified Delphi Study on Key Indicators for Urban Walkability in Gulf Cooperation Council Urban Streets. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Speck, J. Walkable City Rules: 101 Steps to Making Better Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, H. Urban Development in Riyadh: Aligning with Saudi Vision 2030 for Enhanced Quality of Life. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2024, 28, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.; Berry, L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implication for service quality research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, K. Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalmajeed, M. Pedestrian Level of Service (PLOS) Measurement for Footpaths in Commercial Streets. Ph.D. Thesis, Griffith University, Nathan, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shash, A. Factors considered in tendering decisions by top UK contractors. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1993, 11, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, O. Development of a Multi-Criteria Approach for the Selection of Sustainable Materials for Building Projects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Siami, S.; Gorji, M. The measurement of service quality by using SERVQUAL and quality gap model. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 5, 1956–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stradling, S.; Anable, J.; Carreno, M. Performance, importance and user disgruntlement: A six-step method for measuring satisfaction with travel modes. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 2007, 41, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Web survey experiments on matrix questions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, R. Conducting research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2020, 44, 151287. [Google Scholar]

| RII Value | Importance Level |

|---|---|

| () | High (H) |

| () | High-medium (H-M) |

| () | Medium (M) |

| () | Medium-low (M-L) |

| () | low (L) |

| Category | Walkability Indicators | W | N | RII | Importance Level | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Indicators | Accessibility of mosques/prayer rooms | 1285 | 302 | 1510 | 0.851 | H | 1 |

| Wheelchair accessibility to mosques | 1265 | 302 | 1510 | 0.838 | H | 2 | |

| Heat-resistant pavement | 1243 | 302 | 1510 | 0.823 | H | 3 | |

| Weather-resistant street furniture | 1207 | 302 | 1510 | 0.799 | H-M | 4 | |

| Open space markets/galleries | 1193 | 302 | 1510 | 0.790 | H-M | 5 | |

| Functional Indicators | Cleanliness and maintenance of paths and streets | 1308 | 302 | 1510 | 0.866 | H | 1 |

| Availability of parking | 1293 | 302 | 1510 | 0.856 | H | 2 | |

| Pedestrian footpath continuity | 1293 | 302 | 1510 | 0.856 | H | 3 | |

| Absence of obstacles on footpath | 1289 | 302 | 1510 | 0.854 | H | 4 | |

| Quality of footpath pavement surface | 1279 | 302 | 1510 | 0.847 | H | 5 | |

| Accessibility of shops and services | 1263 | 302 | 1510 | 0.836 | H | 6 | |

| Pedestrian path width | 1253 | 302 | 1510 | 0.830 | H | 7 | |

| Public transportation facilities | 1221 | 302 | 1510 | 0.809 | H | 8 | |

| Accessibility of public transit | 1220 | 302 | 1510 | 0.808 | H | 9 | |

| Distribution of land uses | 1211 | 302 | 1510 | 0.802 | H | 10 | |

| Slope | 1165 | 302 | 1510 | 0.772 | H-M | 11 | |

| Safety Indicators | Visibility while crossing street | 1323 | 302 | 1510 | 0.876 | H | 1 |

| Provision of lighting | 1322 | 302 | 1510 | 0.875 | H | 2 | |

| Pedestrian protection from traffic accident risks | 1303 | 302 | 1510 | 0.863 | H | 3 | |

| Presence of security cameras (CCTV) | 1294 | 302 | 1510 | 0.857 | H | 4 | |

| Variety of activities | 1286 | 302 | 1510 | 0.852 | H | 5 | |

| Street signage | 1287 | 302 | 1510 | 0.852 | H | 6 | |

| Pedestrian crossings along streets | 1285 | 302 | 1510 | 0.851 | H | 7 | |

| Pedestrian signals | 1271 | 302 | 1510 | 0.842 | H | 8 | |

| Traffic speed | 1271 | 302 | 1510 | 0.842 | H | 9 | |

| Traffic volume | 1270 | 302 | 1510 | 0.841 | H | 10 | |

| Pedestrian wayfinding signage | 1260 | 302 | 1510 | 0.834 | H | 11 | |

| Absence of abandoned buildings | 1255 | 302 | 1510 | 0.831 | H | 12 | |

| Buffers between streets and footpaths | 1250 | 302 | 1510 | 0.828 | H | 13 | |

| Service hours of activities | 1246 | 302 | 1510 | 0.825 | H | 14 | |

| Pedestrian volume | 1244 | 302 | 1510 | 0.824 | H | 15 | |

| Traffic-calming measures | 1236 | 302 | 1510 | 0.819 | H | 16 | |

| Indicators of Aesthetic Qualities | Presence of trees | 1314 | 302 | 1510 | 0.870 | H | 1 |

| Landscaping along streets | 1275 | 302 | 1510 | 0.844 | H | 2 | |

| Public open spaces | 1266 | 302 | 1510 | 0.838 | H | 3 | |

| Landmarks | 1261 | 302 | 1510 | 0.835 | H | 4 | |

| Proper spacing between trees | 1251 | 302 | 1510 | 0.828 | H | 5 | |

| Buildings with identifiers | 1242 | 302 | 1510 | 0.823 | H | 6 | |

| Comfort Indicators | Public toilets | 1339 | 302 | 1510 | 0.887 | H | 1 |

| Kerb ramp | 1323 | 302 | 1510 | 0.876 | H | 2 | |

| Benches | 1319 | 302 | 1510 | 0.874 | H | 3 | |

| Tactile pavement for visually impaired | 1302 | 302 | 1510 | 0.862 | H | 4 | |

| Air pollution level | 1293 | 302 | 1510 | 0.856 | H | 5 | |

| Distinct, pleasant smells | 1291 | 302 | 1510 | 0.855 | H | 6 | |

| Canopies and shelters | 1288 | 302 | 1510 | 0.853 | H | 7 | |

| Presence of commercial zones/business activities | 1281 | 302 | 1510 | 0.848 | H | 8 | |

| Proper outdoor thermal comfort | 1278 | 302 | 1510 | 0.846 | H | 9 | |

| Level of noise | 1263 | 302 | 1510 | 0.836 | H | 10 | |

| Presence of children’s playground | 1244 | 302 | 1510 | 0.824 | H | 11 |

| Importance of Indicators (Important and Very Important %) | Entire Sample | Male | Female | (18–44) Years | Over 44 Years | Single | Married | Employed | Student | Senior/ Retired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of lighting | 84% | 84% | 84% | 65% | 95% | 81% | 84% | 84% | 79% | 94% |

| Public toilets | 84% | 85% | 84% | 82% | 90% | 84% | 84% | 83% | 79% | 94% |

| Pedestrian footpath continuity | 83% | 84% | 82% | 81% | 87% | 85% | 81% | 81% | 81% | 88% |

| Visibility while crossing street | 83% | 85% | 82% | 80% | 91% | 81% | 83% | 83% | 77% | 94% |

| Presence of trees | 83% | 83% | 84% | 81% | 90% | 80% | 85% | 86% | 73% | 88% |

| Benches | 83% | 83% | 82% | 80% | 90% | 82% | 83% | 81% | 79% | 94% |

| Cleanliness and maintenance of paths and streets | 82% | 83% | 81% | 80% | 89% | 85% | 80% | 80% | 83% | 91% |

| Kerb ramp | 82% | 81% | 84% | 79% | 91% | 81% | 83% | 81% | 77% | 91% |

| Absence of obstacles on footpath | 81% | 85% | 77% | 78% | 90% | 83% | 80% | 81% | 81% | 94% |

| Availability of parking | 81% | 83% | 79% | 80% | 86% | 85% | 79% | 80% | 85% | 88% |

| Variety of activities | 81% | 81% | 80% | 61% | 95% | 78% | 82% | 81% | 75% | 91% |

| Air pollution level | 81% | 81% | 80% | 78% | 89% | 80% | 81% | 83% | 69% | 91% |

| Presence of commercial zones/business activities | 80% | 80% | 81% | 78% | 86% | 79% | 81% | 82% | 71% | 85% |

| Distinct, pleasant smells | 80% | 78% | 82% | 77% | 89% | 82% | 79% | 78% | 71% | 91% |

| Accessibility of mosques/prayer rooms | 79% | 83% | 75% | 78% | 84% | 84% | 77% | 76% | 87% | 91% |

| Pedestrian path width | 79% | 83% | 74% | 75% | 90% | 82% | 78% | 78% | 75% | 94% |

| Pedestrian protection from traffic accident risks | 79% | 79% | 79% | 76% | 87% | 78% | 80% | 78% | 71% | 91% |

| Pedestrian crossings along streets | 79% | 78% | 82% | 77% | 87% | 79% | 79% | 80% | 75% | 85% |

| Street signage | 79% | 79% | 79% | 76% | 89% | 80% | 78% | 77% | 77% | 94% |

| Pedestrian signals | 79% | 77% | 81% | 76% | 87% | 78% | 78% | 77% | 75% | 88% |

| Canopies and shelters | 79% | 79% | 79% | 76% | 87% | 78% | 79% | 77% | 73% | 94% |

| Tactile pavement for visually impaired | 79% | 78% | 80% | 75% | 89% | 78% | 79% | 78% | 75% | 85% |

| Accessibility of shops and services | 78% | 77% | 79% | 75% | 86% | 79% | 77% | 78% | 75% | 85% |

| Presence of security cameras (CCTV) | 78% | 78% | 79% | 76% | 85% | 77% | 79% | 77% | 77% | 88% |

| Traffic volume | 78% | 77% | 79% | 76% | 82% | 77% | 78% | 78% | 71% | 82% |

| Landscaping along streets | 78% | 77% | 80% | 76% | 85% | 77% | 79% | 80% | 71% | 82% |

| Proper outdoor thermal comfort | 78% | 80% | 76% | 74% | 89% | 78% | 78% | 81% | 69% | 85% |

| Quality of footpath pavement surface | 77% | 79% | 76% | 74% | 87% | 79% | 76% | 75% | 77% | 91% |

| Landmarks | 77% | 79% | 76% | 75% | 84% | 76% | 78% | 80% | 75% | 82% |

| Public open spaces | 77% | 76% | 77% | 74% | 86% | 73% | 78% | 79% | 71% | 85% |

| Wheelchair accessibility to mosques | 76% | 78% | 75% | 74% | 82% | 82% | 74% | 74% | 83% | 85% |

| Absence of abandoned buildings | 76% | 73% | 80% | 74% | 84% | 72% | 78% | 74% | 71% | 91% |

| Traffic speed | 76% | 75% | 78% | 74% | 85% | 74% | 76% | 75% | 71% | 88% |

| Pedestrian wayfinding signage | 76% | 76% | 77% | 73% | 86% | 76% | 77% | 74% | 71% | 88% |

| Pedestrian volume | 76% | 73% | 79% | 73% | 84% | 77% | 75% | 74% | 73% | 82% |

| Proper spacing between trees | 76% | 76% | 76% | 73% | 86% | 71% | 78% | 78% | 67% | 85% |

| Heat-resistant pavement | 75% | 76% | 74% | 73% | 81% | 77% | 73% | 74% | 73% | 82% |

| Service hours of activities | 75% | 73% | 77% | 72% | 84% | 74% | 74% | 74% | 69% | 79% |

| Buffers between streets and footpaths | 75% | 71% | 79% | 73% | 80% | 76% | 73% | 72% | 75% | 82% |

| Buildings with identifiers | 75% | 71% | 80% | 73% | 84% | 74% | 76% | 75% | 73% | 79% |

| Presence of children’s playground | 75% | 72% | 78% | 73% | 81% | 77% | 74% | 72% | 73% | 79% |

| Level of noise | 75% | 75% | 75% | 71% | 85% | 81% | 72% | 74% | 69% | 88% |

| Traffic-calming measures | 74% | 74% | 75% | 72% | 81% | 74% | 73% | 73% | 69% | 79% |

| Public transportation facilities | 73% | 74% | 73% | 71% | 80% | 78% | 70% | 70% | 77% | 76% |

| Weather-resistant street furniture | 72% | 73% | 70% | 70% | 76% | 72% | 71% | 71% | 69% | 79% |

| Open space markets/galleries | 72% | 74% | 71% | 70% | 78% | 71% | 72% | 72% | 67% | 85% |

| Accessibility of public transit | 72% | 71% | 73% | 68% | 81% | 74% | 69% | 68% | 77% | 79% |

| Distribution of land uses | 71% | 66% | 77% | 70% | 73% | 69% | 71% | 67% | 75% | 76% |

| Slope | 67% | 66% | 68% | 65% | 75% | 67% | 67% | 66% | 71% | 73% |

| Performance of Indicators (Satisfied and Very Satisfied %) | Entire Sample | Male | Female | (18–44) Years | Over 44 Years | Single | Married | Employed | Student | Senior/ Retired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision of lighting | 62% | 63% | 62% | 62% | 63% | 64% | 62% | 60% | 62% | 70% |

| Accessibility of mosques/prayer rooms | 61% | 63% | 58% | 64% | 51% | 70% | 56% | 59% | 77% | 42% |

| Visibility while crossing street | 60% | 66% | 55% | 61% | 61% | 59% | 62% | 59% | 62% | 67% |

| Variety of activities | 57% | 62% | 53% | 56% | 62% | 61% | 57% | 57% | 63% | 61% |

| Street signage | 53% | 56% | 50% | 53% | 53% | 57% | 52% | 49% | 65% | 52% |

| Traffic speed | 48% | 52% | 45% | 52% | 39% | 55% | 47% | 46% | 62% | 42% |

| Accessibility of shops and services | 47% | 47% | 49% | 47% | 49% | 49% | 46% | 48% | 46% | 52% |

| Presence of commercial zones/business activities | 47% | 51% | 43% | 50% | 39% | 53% | 44% | 48% | 50% | 33% |

| Pedestrian path width | 46% | 41% | 52% | 48% | 42% | 51% | 44% | 40% | 60% | 45% |

| Open space markets/galleries | 46% | 49% | 42% | 46% | 44% | 52% | 44% | 46% | 54% | 30% |

| Service hours of activities | 46% | 48% | 44% | 48% | 42% | 51% | 45% | 43% | 50% | 42% |

| Landmarks | 44% | 41% | 48% | 48% | 33% | 54% | 40% | 43% | 52% | 21% |

| Public open spaces | 44% | 42% | 47% | 47% | 37% | 54% | 40% | 44% | 54% | 30% |

| Pedestrian volume | 44% | 45% | 43% | 45% | 41% | 44% | 46% | 43% | 50% | 39% |

| Cleanliness and maintenance of paths and streets | 43% | 47% | 40% | 43% | 43% | 46% | 43% | 44% | 48% | 39% |

| Wheelchair accessibility to mosques | 43% | 40% | 47% | 46% | 37% | 49% | 41% | 39% | 54% | 30% |

| Buildings with identifiers | 43% | 37% | 50% | 46% | 34% | 54% | 39% | 40% | 56% | 21% |

| Presence of trees | 43% | 39% | 47% | 45% | 38% | 45% | 42% | 43% | 40% | 33% |

| Traffic volume | 42% | 40% | 46% | 45% | 35% | 47% | 41% | 41% | 48% | 27% |

| Presence of security cameras (CCTV) | 40% | 40% | 42% | 42% | 37% | 45% | 40% | 38% | 50% | 27% |

| Proper spacing between trees | 40% | 40% | 41% | 43% | 33% | 45% | 40% | 43% | 38% | 21% |

| Pedestrian crossings along streets | 40% | 37% | 44% | 42% | 37% | 45% | 39% | 37% | 54% | 27% |

| Traffic-calming measures | 40% | 35% | 46% | 42% | 35% | 43% | 39% | 35% | 44% | 33% |

| Quality of footpath pavement surface | 39% | 35% | 45% | 44% | 27% | 54% | 33% | 35% | 54% | 24% |

| Pedestrian protection from traffic accident risks | 39% | 40% | 38% | 40% | 35% | 48% | 37% | 36% | 48% | 30% |

| Landscaping along streets | 38% | 33% | 44% | 41% | 32% | 43% | 37% | 37% | 38% | 21% |

| Pedestrian footpath continuity | 38% | 35% | 42% | 41% | 32% | 40% | 38% | 36% | 44% | 24% |

| Pedestrian signals | 38% | 36% | 41% | 42% | 28% | 43% | 36% | 38% | 42% | 18% |

| Absence of obstacles on footpath | 37% | 32% | 44% | 41% | 28% | 49% | 33% | 33% | 58% | 21% |

| Availability of parking | 37% | 35% | 40% | 39% | 34% | 43% | 36% | 33% | 52% | 33% |

| Buffers between streets and footpaths | 37% | 36% | 38% | 40% | 28% | 46% | 34% | 31% | 56% | 24% |

| Pedestrian wayfinding signage | 37% | 32% | 42% | 41% | 27% | 40% | 36% | 33% | 40% | 27% |

| Presence of children’s playground | 37% | 31% | 43% | 42% | 23% | 50% | 31% | 32% | 50% | 24% |

| Distribution of land uses | 36% | 32% | 42% | 40% | 27% | 44% | 34% | 34% | 46% | 24% |

| Slope | 36% | 39% | 34% | 40% | 27% | 36% | 37% | 41% | 37% | 18% |

| Benches | 35% | 33% | 37% | 41% | 19% | 48% | 29% | 32% | 54% | 12% |

| Kerb ramp | 34% | 33% | 36% | 38% | 25% | 40% | 33% | 35% | 40% | 15% |

| Absence of abandoned buildings | 34% | 32% | 37% | 39% | 22% | 44% | 32% | 31% | 48% | 15% |

| Heat-resistant pavement | 34% | 29% | 38% | 38% | 22% | 43% | 29% | 32% | 46% | 9% |

| Public transportation facilities | 32% | 26% | 38% | 34% | 27% | 38% | 30% | 28% | 44% | 15% |

| Canopies and shelters | 32% | 28% | 36% | 36% | 22% | 44% | 27% | 28% | 46% | 18% |

| Tactile pavement for visually impaired | 32% | 29% | 36% | 38% | 16% | 44% | 27% | 29% | 44% | 12% |

| Level of noise | 31% | 32% | 32% | 35% | 23% | 38% | 30% | 32% | 37% | 15% |

| Air pollution level | 30% | 26% | 36% | 36% | 15% | 39% | 27% | 28% | 38% | 18% |

| Accessibility of public transit | 30% | 23% | 38% | 34% | 22% | 38% | 27% | 25% | 44% | 15% |

| Weather-resistant street furniture | 29% | 27% | 32% | 33% | 20% | 37% | 26% | 26% | 46% | 15% |

| Public toilets | 29% | 27% | 33% | 35% | 15% | 38% | 26% | 27% | 42% | 15% |

| Proper outdoor thermal comfort | 29% | 27% | 32% | 35% | 14% | 36% | 27% | 29% | 37% | 12% |

| Distinct pleasant smells | 28% | 23% | 34% | 35% | 10% | 36% | 26% | 27% | 33% | 6% |

| Importance Level (%) | Total (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at All Important | Slightly Important | Neutral | Important | Very Important | |||

| Dissatisfied | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.33%) | 31 (10.26%) | 35 (11.59%) | |

| Very dissatisfied | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.33%) | - | 2 (0.66%) | 11 (3.64%) | 15 (4.97%) | |

| Satisfaction level (%) | Neutral | 3 (0.99%) | 10 (3.31%) | 10 (3.31%) | 8 (2.65%) | 33 (10.93%) | 64 (21.19%) |

| Satisfied | 2 (0.66%) | 10 (3.31%) | 3 (0.99%) | 31 (10.26%) | 74 (24.50%) | 120 (39.74%) | |

| Very satisfied | 3 (0.99%) | 1 (0.33%) | 2 (0.66%) | 5 (1.66%) | 57 (18.87%) | 68 (22.52%) | |

| Disgruntlement of Indicators (%) | Entire Sample | Male | Female | (18–44) Years | Over 44 Years | Single | Married | Employed | Student | Senior/ Retired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public toilets | 49% | 53% | 43% | 43% | 64% | 43% | 51% | 52% | 35% | 67% |

| Benches | 41% | 44% | 35% | 34% | 56% | 30% | 45% | 46% | 18% | 58% |

| Canopies and shelters | 39% | 49% | 28% | 35% | 51% | 27% | 46% | 48% | 21% | 53% |

| Availability of parking | 38% | 42% | 34% | 35% | 46% | 31% | 40% | 42% | 26% | 55% |

| Proper outdoor thermal comfort | 37% | 38% | 34% | 30% | 52% | 29% | 39% | 39% | 26% | 53% |

| Air pollution level | 37% | 43% | 29% | 31% | 49% | 31% | 39% | 40% | 29% | 41% |

| Kerb ramp | 34% | 40% | 28% | 30% | 45% | 25% | 39% | 37% | 31% | 44% |

| Level of noise | 34% | 35% | 32% | 31% | 41% | 31% | 34% | 36% | 30% | 34% |

| Distinct, pleasant smells | 33% | 35% | 31% | 29% | 44% | 27% | 35% | 33% | 28% | 50% |

| Weather-resistant street furniture | 33% | 41% | 25% | 29% | 44% | 27% | 36% | 38% | 20% | 49% |

| Landscaping along streets | 33% | 36% | 28% | 30% | 38% | 26% | 36% | 37% | 28% | 36% |

| Tactile pavement for visually impaired | 32% | 34% | 30% | 31% | 37% | 29% | 34% | 34% | 33% | 29% |

| Absence of obstacles on footpath | 31% | 39% | 22% | 27% | 40% | 25% | 34% | 35% | 22% | 45% |

| Heat-resistant pavement | 30% | 37% | 24% | 27% | 42% | 22% | 35% | 36% | 19% | 46% |

| Presence of trees | 30% | 36% | 23% | 27% | 37% | 22% | 34% | 33% | 27% | 38% |

| Pedestrian crossings along streets | 29% | 35% | 23% | 28% | 33% | 28% | 30% | 36% | 23% | 28% |

| Quality of footpath pavement surface | 28% | 33% | 23% | 25% | 37% | 22% | 32% | 32% | 15% | 41% |

| Pedestrian signals | 28% | 30% | 25% | 26% | 33% | 27% | 28% | 27% | 33% | 35% |

| Public transportation facilities | 27% | 37% | 17% | 23% | 40% | 20% | 31% | 36% | 15% | 32% |

| Absence of abandoned buildings | 27% | 30% | 23% | 23% | 37% | 18% | 30% | 28% | 21% | 41% |

| Cleanliness and maintenance of paths and streets | 27% | 27% | 27% | 28% | 25% | 28% | 28% | 27% | 31% | 25% |

| Accessibility of public transit | 27% | 33% | 19% | 21% | 43% | 19% | 30% | 33% | 12% | 40% |

| Pedestrian protection from traffic accident risks | 27% | 33% | 21% | 28% | 23% | 25% | 28% | 30% | 25% | 23% |

| Presence of security cameras (CCTV) | 27% | 30% | 22% | 24% | 34% | 17% | 31% | 30% | 18% | 39% |

| Pedestrian wayfinding signage | 27% | 34% | 18% | 24% | 34% | 19% | 31% | 32% | 26% | 25% |

| Pedestrian footpath continuity | 27% | 32% | 20% | 23% | 34% | 16% | 31% | 32% | 10% | 30% |

| Pedestrian path width | 26% | 31% | 20% | 24% | 30% | 19% | 29% | 30% | 17% | 29% |

| Traffic volume | 25% | 31% | 19% | 26% | 24% | 25% | 27% | 29% | 25% | 17% |

| Wheelchair accessibility to mosques | 25% | 29% | 19% | 24% | 25% | 26% | 24% | 30% | 25% | 20% |

| Presence of children’s playground | 25% | 28% | 22% | 21% | 37% | 17% | 29% | 28% | 19% | 32% |

| Buffers between streets and footpaths | 23% | 27% | 17% | 19% | 30% | 16% | 25% | 26% | 13% | 32% |

| Proper spacing between trees | 23% | 25% | 18% | 21% | 23% | 21% | 22% | 21% | 27% | 21% |

| Buildings with identifiers | 21% | 24% | 17% | 18% | 29% | 13% | 24% | 24% | 9% | 29% |

| Landmarks | 20% | 24% | 15% | 17% | 27% | 11% | 24% | 25% | 12% | 24% |

| Traffic speed | 20% | 20% | 19% | 17% | 27% | 15% | 21% | 19% | 16% | 24% |

| Public open spaces | 19% | 20% | 18% | 17% | 25% | 11% | 23% | 22% | 14% | 12% |

| Accessibility of shops and services | 19% | 18% | 18% | 18% | 19% | 18% | 19% | 21% | 17% | 17% |

| Traffic-calming measures | 19% | 26% | 10% | 16% | 24% | 15% | 20% | 22% | 21% | 18% |

| Slope | 18% | 17% | 17% | 17% | 19% | 17% | 17% | 16% | 21% | 11% |

| Street signage | 17% | 16% | 19% | 17% | 18% | 12% | 20% | 19% | 13% | 22% |

| Open space markets/galleries | 16% | 21% | 9% | 13% | 22% | 12% | 17% | 17% | 7% | 30% |

| Service hours of activities | 15% | 17% | 13% | 13% | 21% | 11% | 17% | 17% | 13% | 13% |

| Pedestrian volume | 15% | 15% | 14% | 14% | 15% | 10% | 16% | 16% | 9% | 14% |

| Distribution of land uses | 15% | 11% | 18% | 14% | 17% | 9% | 17% | 15% | 9% | 18% |

| Provision of lighting | 15% | 13% | 16% | 15% | 13% | 18% | 13% | 14% | 21% | 4% |

| Presence of commercial zones/business activities | 15% | 13% | 15% | 13% | 18% | 12% | 15% | 15% | 15% | 20% |

| Visibility while crossing street | 14% | 15% | 12% | 13% | 16% | 11% | 15% | 14% | 8% | 13% |

| Variety of activities | 14% | 12% | 15% | 15% | 10% | 15% | 13% | 13% | 12% | 2% |

| Accessibility of mosques/prayer rooms | 13% | 13% | 13% | 11% | 19% | 11% | 14% | 16% | 4% | 20% |

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Intra-City distribution | ||||

| Male | 156 | 52% | Central of Riyadh | 46 | 15% |

| Female | 146 | 48% | North of Riyadh | 108 | 36% |

| Age group | East of Riyadh | 78 | 26% | ||

| 18–24 years | 62 | 21% | West of Riyadh | 32 | 11% |

| 25–34 years | 86 | 28% | South of Riyadh | 33 | 11% |

| 35–44 years | 75 | 25% | Walking capability | ||

| 45–54 years | 45 | 15% | Excellent | 139 | 46% |

| 55–64 years | 25 | 8% | Very good | 98 | 32% |

| 65–74 | 9 | 3% | Good | 50 | 17% |

| Over 75 years | 0 | 0% | Fair | 13 | 4% |

| Marital status | Poor | 2 | 1% | ||

| Single | 94 | 31% | Car availability | ||

| Married with children | 169 | 56% | Yes, always | 212 | 70% |

| Married and no children | 30 | 10% | Yes, sometimes | 79 | 26% |

| Widowed | 2 | 1% | No | 11 | 4% |

| Divorced | 7 | 2% | Nationality | ||

| Employment status | Saudi | 288 | 95% | ||

| Employed | 167 | 55% | Non-Saudi | 14 | 5% |

| Senior/retired | 33 | 11% | Household income | ||

| Student | 77 | 25% | SAR 4000 or less | 37 | 12% |

| Unemployed | 25 | 8% | SAR 4001–8000 | 53 | 18% |

| Level of education | SAR 8001–12,000 | 66 | 22% | ||

| Primary | 3 | 1% | SAR 12,001–16,000 | 53 | 18% |

| Intermediate | 5 | 2% | SAR 16,001–20,000 | 34 | 11% |

| High school | 58 | 19% | SAR > 20,000 | 58 | 19% |

| Certificate/diploma (2 yrs) | 34 | 11% | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 154 | 51% | |||

| Master’s degree | 39 | 13% | |||

| PhD | 9 | 3% |

| Comments | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Walking in Riyadh is a challenge | 140 | 79.6 |

| Walking in Riyadh is positive | 29 | 16.4 |

| No experience, I have only visited GCC countries | 7 | 4.0 |

| Comments | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Functional considerations | 49 | 21.1 |

| Safety considerations | 43 | 18.5 |

| Environmental considerations | 39 | 16.8 |

| Comfort considerations | 33 | 14.2 |

| Regulation and legal considerations | 26 | 11.2 |

| Cultural considerations | 24 | 10.3 |

| Considerations of aesthetic qualities | 18 | 7.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkrides, B.F.; Washington, T.; Limb, M.; Cushing, D. Assessing Walkability in Riyadh’s Commercial Streets: Public Perceptions and Prioritization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135748

Alkrides BF, Washington T, Limb M, Cushing D. Assessing Walkability in Riyadh’s Commercial Streets: Public Perceptions and Prioritization. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135748

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkrides, Bander Fahad, Tracy Washington, Mark Limb, and Debra Cushing. 2025. "Assessing Walkability in Riyadh’s Commercial Streets: Public Perceptions and Prioritization" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135748

APA StyleAlkrides, B. F., Washington, T., Limb, M., & Cushing, D. (2025). Assessing Walkability in Riyadh’s Commercial Streets: Public Perceptions and Prioritization. Sustainability, 17(13), 5748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135748