Strategic Business Model Development for Sustainable Fashion Startups: Insights from the BANU Case in Senegal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study Selection

3.2. Analysis Framework

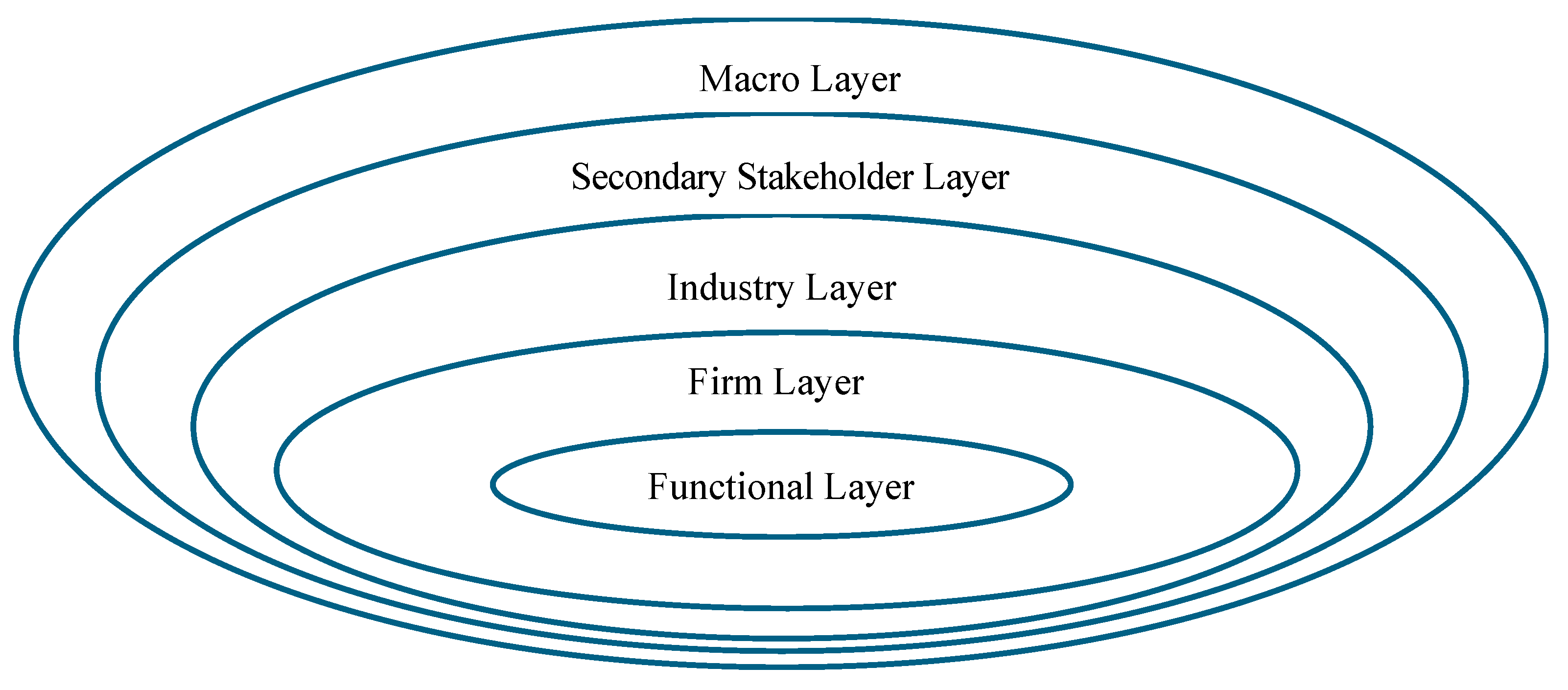

- Macro Layer: This layer represents the broad forces influencing environmental governance, referred to as PESTEL forces (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal). These forces shape how businesses in different nations manage environmental governance.

- Micro Layer:

- ○

- Secondary Stakeholder Layer: Based on stakeholder theory, businesses must balance strategic goals to meet the expectations of diverse stakeholders. Secondary stakeholders, while less directly involved, significantly influence a firm’s success.

- ○

- Industry Layer: Porter’s Five Forces framework highlights how industry dynamics affect long-term success. Industry-specific factors related to environmental governance also impact firms’ strategies.

- Organization Layer:

- ○

- Firm Layer: Firm-specific forces, such as ownership structure and asset attributes, influence investments in environmental governance.

- ○

- Functional Layer: This layer encompasses actions directly impacting market value, revenue, or costs. These actions align with “economic rationality,” where environmental strategies are adopted to enhance financial stability.

3.3. Data Collection Methods and Analysis Tools

- Literature Review: Provides theoretical context, methodological guidance, and a foundation for meaningful contributions to existing knowledge.

- Interviews: Primary data were collected from BANU (1 participant), an Entrepreneurship Center & Incubator in the UAE (1 participant), and Senegalese companies based in the UAE (5–7 participants). Respondents were selected for their industry expertise and involvement to address key research questions.

- Survey: A survey was distributed via SurveyMonkey to 75–100 local and international stakeholders and customers to understand preferences in Senegal’s fashion industry.

- The findings are context-specific and not statistically generalizable beyond the case.

- Survey results may reflect regional or cultural bias due to concentration in the Senegalese and UAE fashion communities.

- Interview responses may vary in depth depending on participants’ professional exposure.

| Layer/Sub-Layer | Tool | Data Collection Tool | Target Population | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macro layer | ||||

| Macro layer | PESTEL analysis | Literature review | Local and international stakeholder and customers | Identifying a set of key influences that effect the competitive environment |

| Micro layer | ||||

| Secondary stakeholder layer | Customer analysis | Customer and stakeholder analysis through market and segmentation studies using a survey Interview | Local and international stakeholders and customers Entrepreneurship Center & Incubator | Identifying the target market as well as the current and potential clients How the market is divided into segments and how each segment is positioned |

| Industry layer | Five Forces framework | Literature review Interview | Senegalese companies | Static and descriptive analysis of competitive forces |

| Organization layer | ||||

| Firm layer | Market-based view and resource-based view (VRIO framework) | Interview | BANU | Industry environment and the firm’s competitive position Assessing resources and capabilities that build competitive advantage |

| Functional layer | Value chain analysis | Interview | BANU | Assessing financial strategy, brand protection strategy, quality strategy and cost control strategies Helps to analyze specific activities through which firms can create value and competitive advantage |

4. Case Study Analysis

4.1. Macro Layer Analysis

- Political: While Senegal has a history of political stability [58], issues such as corruption [59], preferential treatment, and inefficiencies in the legal system create barriers, particularly for female-led businesses [60]. Reforms are needed to enhance transparency, simplify export laws, and strengthen judicial independence.

- Economical: Senegal’s strategic location near the North Atlantic Ocean offers significant trade opportunities, but low economic development and poor infrastructure [61], such as traffic congestion, hinder growth [55]. Since the 2014 Emerging Senegal Plan, economic growth has averaged over 6% [58]. However, SMEs face challenges like limited access to finance, high collateral requirements, and complex tax procedures [62]. Efforts such as investment guarantees and trade facilitation reforms show promise but need further enhancement to benefit smaller enterprises [58,59,62].

- Social: Education and labor competence remain low, with only 29% of the population completing secondary education [62]. While the government promotes women and youth participating in agriculture and entrepreneurship, challenges persist, such as restricted access to loans and property for women [59]. The global export industry creates job opportunities, especially for women, but high production demands can lead to labor shortages and job insecurity [62].

- Technological: Senegal’s digital economy faces slow development due to poor governance, limited innovation policies, and inadequate infrastructure. The government has committed to improvements, including better regulation, infrastructure sharing, and integrating digital technology into education [62].

- Environmental: Senegal suffers from energy deficits and poor water quality, especially in rural areas [62,63]. Renewable energy laws aim to promote solar energy and biofuel production, but no specific environmental laws target SMEs. Water sanitation remains uneven, with high tariffs limiting business growth [62].

4.2. Micro Layer Analysis

4.2.1. Secondary Stakeholder/Customer Layer Analysis

- Market Identification: A survey of 78 Gulf region customers revealed preferences for traditional (37.18%), formal (34.62%), and casual clothing. Bright colors, patterns, and classic styles are favored, with most shopping quarterly (52.56%) or monthly (37.18%) via online stores and brand websites. Discounts (43.59%) and brand reputation (38.46%) significantly influence purchasing decisions, while environmental responsibility has minimal impact (47.44%).

- Market segmentation: This involves categorizing customers by geography, demographics, psychographics, and behavior, as indicated in Table 3. BANU can utilize geographic segmentation to expand into GCC markets and demographic segmentation to target customers by age, gender, and income. Over time, psychographic and behavioral segmentation will help refine customer experiences and diversify offerings.

- Market position: This helps BANU create a unique image and competitive advantage. An expert interview recommended BANU leverage its Senegalese roots by supporting education, training, employment, and women’s empowerment to differentiate itself in global markets. Initial expansion should focus on online platforms with targeted marketing, transitioning to physical stores once demand is established. BANU’s social impact can significantly influence purchasing decisions and build customer loyalty.

4.2.2. The Industry Layer Analysis

- Threat of New Entrants: Barriers to entry are low due to simple registration processes and minimal government requirements. However, the textile industry has declined significantly since the 1990s, resulting in unemployment and a loss of knowledge [66]. Seven Senegalese company owners highlight through the interview that family-run businesses dominate the sector, with limited competition and no significant government support for expansion. Also, Senegalese distribution channels lack online purchasing capabilities, with most local customers opting for physical stores, shops, or business owners’ homes.

- Bargaining Power of Buyers: Buyer power is low, as customers prefer Senegalese pure cotton textiles and rely on local markets. However, natural dye fabrics’ tendency to lose color after washes can affect customer retention. International trade leverages group distribution channels for cost efficiency, while customization is time-consuming and resource dependent.

- Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Senegal’s suppliers consist of small family businesses with varied pricing and quality. Dependency on family farms for raw materials is high, with occasional reliance on neighboring countries during shortages. The absence of an official supplier network results in low-to-medium supplier power, as their success depends on buyer demand and relationships.

- Threat of Substitutes: Substitution is high, as customers often choose international brands over traditional natural textiles. Competitive pricing and product performance further limit the industry’s profit margins.

- Industry Rivalry: Competition within the Senegalese fashion industry is minimal, focusing more on family survival than on innovation. Growth is constrained by financial challenges, lack of technical development, and limited marketing. Knowledge sharing relies on personal networks, with no dedicated institutions for training or formalizing the sector.

4.3. Organization Layer Analysis

4.3.1. The Firm Layer

- Tangible Resources: Raw materials, workshops, and stores.

- Intangible Resources: Unique traditional designs, cultural heritage, and expertise passed down through generations.

- Human Resources: Skilled designers and collaborative efforts with families, fostering community bonds.

- Value: BANU offers eco-friendly products with a transparent supply chain, leveraging local cotton and traditional dyeing techniques. Its sustainable practices and cultural authenticity resonate with customers, driving brand loyalty and market competitiveness.

- Rarity: Authentic cultural designs and sustainable practices are scarce in the GCC market. The initiative’s focus on empowering families and preserving heritage makes its offering unique.

- Imitability: While designs and capabilities can be replicated, the personal stories behind the brand and its deep cultural roots are hard to imitate.

- Organization: BANU’s organizational culture promotes sustainability and social responsibility. Efficient resource allocation, budgeting, and supply chain management ensure effective market adaptation and logistics for GCC expansion.

4.3.2. The Functional Layer

4.4. SWOT and TWOS Analysis

4.5. Strategy Recommendations

4.5.1. Strategic Issues

4.5.2. Strategic Choices

4.5.3. Practical Implementation Considerations

- Strengthening Local Operational Capacity

- Skills Development: Establish localized training programs in partnership with vocational institutions and NGOs to enhance technical knowledge in traditional dyeing and weaving techniques. These initiatives should prioritize the inclusion of women and youth to foster inclusive economic development.

- Supply Chain Formalization: Create cooperative networks among small-scale cotton growers and dye artisans to improve raw material quality, ensure continuity of supply, and reduce dependence on informal arrangements.

- Quality Assurance Systems: Introduce simple quality checkpoints across the production process to maintain consistency, reduce defects, and enhance product reliability in both local and export markets.

- Leveraging Strategic Partnerships

- Collaboration with NUNU Design: Formalize collaboration channels for design support, co-branding, and resource sharing, allowing BANU to benefit from NUNU’s established market presence and creative capabilities.

- Engagement with Government Programs: Access national support schemes such as DER-FJ or APIX to secure funding, export logistics support, and promotional opportunities in international trade fairs.

- Digital Market Expansion

- E-Commerce Enablement: Develop a bilingual digital storefront equipped for international payments and shipping, targeting diasporic and sustainability-conscious consumers in the GCC and Europe.

- Social Impact Branding: Use multimedia storytelling to communicate BANU’s social mission—emphasizing community empowerment, sustainable practices, and cultural preservation—thereby differentiating the brand in competitive global markets.

- Product–Market Fit and Diversification

- Dual Product Lines: Implement a two-tier product strategy: premium, artisan-quality pieces for export markets, and culturally aligned, affordable items for the domestic market. This dual approach balances profitability with cultural relevance.

- Customer Feedback Integration: Conduct periodic digital surveys and focus groups in both domestic and international markets to align product development with consumer preferences.

- Infrastructure Optimization

- Decentralized Production Units: Invest in small-scale, solar-powered production hubs in rural areas to address unreliable electricity access and to support community-based employment.

- Agile Inventory Management: Adopt limited-batch or made-to-order production models to manage costs, reduce waste, and maintain flexibility in response to market demand.

4.5.4. Strategy Evaluation and Implementation

4.5.5. Vision, Mission, and Values

- Vision: BANU foresees a dynamic future in which the rich cultural heritage of Africa actively contributes to a world that is both sustainable and culturally enriched. The ambition is to establish a global benchmark for genuine, entirely naturally produced textile products that showcase the craftsmanship of traditional natural dyeing and weaving methods, creating a bridge between historical traditions and contemporary realities by empowering Senegalese families to produce 100% Senegalese-made clothing.

- Mission: BANU’s mission is to lead the way in sustainable African cultural products within the fashion and textile industry. The aim is to blend the cultural element, economic impact, and eco-friendly practices, providing actionable insights for the startup’s growth. Through community engagement, alignment with African traditions, and a focus on sustainability, the strive is to differentiate BANU in the local and international markets.

- Values: The values that are listed below highlight the value that BANU aims to add to the fashion industry, focusing on the cultural and sustainable elements.

- ○

- Cultural Preservation: BANU is committed to sustaining and celebrating African heritage fashion by preserving traditional weaving and natural dyeing techniques, ensuring they endure for future generations.

- ○

- Sustainability: From locally sourced and spun cotton to natural dyeing that minimizes environmental impact, BANU is committed to creating products that not only look beautiful but also are eco-friendly.

- ○

- Authenticity: Keeping African craftmanship embedded in the cultural fashion is an essential value that BANU aims to sustain.

- ○

- Innovation: While tradition is the foundation, BANU promotes creativity and innovation in designs and sustainable methods of production. Investment in experiments and research facilities to enrich weaving methods is important, allowing for improvements while preserving the essence of African tradition.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turhan, S.N.; Vayvay, Ö. Vendor managed inventory via SOA in healthcare supply chain management. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2012, 9, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.R.U. Fostering Resilience: The Symbiotic Relationship Between Entrepreneurship and Sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. (IJISRT) 2024, 1391–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokeza, G.; Josipović, S.; Urošević, S. Innovative entrepreneurship as a key factor in creating a sustainable textile and fashion industry. In Proceedings of the VII Međunarodna Naučna Konferencija Savremeni Trendovi i Inovacije U Tekstilnoj Industriji= VII International Scientific Conference Contemporary Trends and Innovations in the Textile Industry, CT&ITI, Belgrade, Serbia, 19–20 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.; Santos, G. Sustainability and biotechnology–natural or bio dyes resources in textiles. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2016, 6, 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Elsahida, K.; Fauzi, A.M.; Sailah, I.; Siregar, I.Z. Sustainable production of natural textile dyes industry. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mukendi, A.; Davies, I.; Glozer, S.; McDonagh, P. Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 2873–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, M.I.; Pogutz, S. Business; ecosystems, and biodiversity: New horizons for management research. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.; Li, Y. Sustainability in fashion business operations. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15400–15406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosman, H.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Brun, A. From a systematic literature review to a classification framework: Sustainability integration in fashion operations. Sustainability 2016, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.J. Traditional fashion practice and cultural sustainability: A case study of nubi in Korea. Fash. Pract. 2023, 15, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruteri, J.M. Overview on textile and fashion industry in tanzania: A need to realize its potential in poverty alleviation. In Quality Education and International Partnership for Textile and Fashion: Hidden Potentials of East Africa; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, S.; Raja, A. Natural dyes: Sources; chemistry, application and sustainability issues. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing: Eco-Friendly Raw Materials, Technologies, and Processing Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzicato, B.; Pacifico, S.; Cayuela, D.; Mijas, G.; Riba-Moliner, M. Advancements in sustainable natural dyes for textile applications: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Yang, X. A recent (2009–2021) perspective on sustainable color and textile coloration using natural plant resources. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerin, I.; Farzana, N.; Muhammad Sayem, A.; Anang, D.M.; Haider, J. Potentials of natural dyes for textile applications. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alegbe, E.O.; Uthman, T.O. A review of history, properties, classification, applications and challenges of natural and synthetic dyes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, K.; Green, D.N.; Haar, S. Natural Dyes in the United States: An Exploration of Natural Dye Use Through the Lens of the Circuit of Style-Fashion-Dress. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2024, 42, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.; Gardas, B.B.; Narkhede, B. Ranking the barriers of sustainable textile and apparel supply chains: An interpretive structural modelling methodology. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. Researching entrepreneurships’ role in sustainable development. In Trailblazing in Entrepreneurship: Creating New Paths for Understanding the Field; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 149–179. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The entrepreneur–environment nexus: Uncertainty; innovation, and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimanzi, M. The Role of Higher Education Institutions in Fostering Innovation and Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Case of a University in South Africa. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11462/2411 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Rodríguez-García, M.; Guijarro-García, M.; Carrilero-Castillo, A. An overview of ecopreneurship, eco-innovation, and the ecological sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abereijo, I.O. Ensuring environmental sustainability through sustainable entrepreneurship. In Sustainable Development: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, M. Challenges Facing Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Three Seas Econ. J. 2024, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Housani, M.I.; Koç, M.; Al-Sada, M.S. Investigations on entrepreneurship needs, challenges, and models for countries in transition to sustainable development from resource-based economy—Qatar as a case. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfazzi, F. The Analysis of Challenges and Prospects Faced by Entrepreneurs to Ensure Sustainable Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises. Acad. Rev. 2023, 1, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauermann, M.P. Social Entrepreneurship as a Tool to Promoting Sustainable Development in Low-Income Communities: An Empirical Analysis. 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4400669 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Stephen, K.M. The Impact of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Achieving Sustainable Development Growth in Zambia. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383167673_THE_IMPACT_OF_SMALL_AND_MEDIUM-SCALE_ENTERPRISES_IN_ACHIEVING_SUSTAINABLE_DEVELOPMENT_GROWTH_IN_ZAMBIA (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Shahid, M.S.; Hossain, M.; Shahid, S.; Anwar, T. Frugal innovation as a source of sustainable entrepreneurship to tackle social and environmental challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 137050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Pillai K, R. Sustainable entrepreneurship research in emerging economies: An evidence from systematic review. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2024, 16, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, W. Deities, Dyers, and Dollars: Balancing Culture, Conservation, and Commerce with Indonesia’s Indigenous Weavers. TEXTILE 2019, 17, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NingShan, H.; Dragomir, V.D. The characteristics and institutional factors of sustainable business models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, Bucharest, Romania, 20–22 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, K. Sustainable Business Models: Balancing Profitability and Environmental Impact. Bull. Manag. Rev. 2023, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, S.; Hagenbeck, J.; Schaltegger, S. Linking sustainable business models and supply chains—Toward an integrated value creation framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3960–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparin, M.; Green, W.; Lilley, S.; Quinn, M.; Saren, M.; Schinckus, C. Business as unusual: A business model for social innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; De Crescenzo, V.; Simeoni, F.; Adaui, C.R.L. Convergences and divergences in sustainable entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship research: A systematic review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhisha, H.; Ramaprasad, B.S.; Sankaran, K.; Nandan Prabhu, K.P.; Phadke, R. Do the Prevalent Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Factors Drive the Choice of Business Models? A Mixed-methods Study Involving Social Entrepreneurs in India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Bansal, S. The impact of the fashion industry on the climate and ecology. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, F.; Caferra, R.; Morone, P. In need of a sustainable and just fashion industry: Identifying challenges and opportunities through a systematic literature review in a Global North/Global South perspective. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krywalski-Santiago, J. Navigating Sustainable Transformation in the Fashion Industry: The Role of Circular Economy and Ethical Consumer Behavior. J. Intercult. Manag. 2024, 16, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, T.S.; Johannsdottir, L. Corporate social responsibility influencing sustainability within the fashion industry. A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Thang, L.N.V.; Nguyen, T.; Gaimster, J.; Morris, R.; George, M. Sustainable developments and corporate social responsibility in Vietnamese fashion enterprises. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 26, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, A.A.; Liu, H. Role of corporate social responsibility authenticity in developing perceived brand loyalty: A consumer perceptions paradigm. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Martinez, I.; Peiro-Signes, A. Transitioning towards sustainability: The ‘what’,‘why’and ‘how’of the integration of sustainable practices into business models. Tec Empres. 2022, 16, 44–67. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre, W.J.; Fonseca, A.; Morioka, S.N. Strategic sustainability integration: Merging management tools to support business model decisions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2052–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Population Fund, World Population Dashboard -Senegal | United Nations Population Fund. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/SN (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Roll, N. Dressing Dakar: A fashion city from artisan tailoring to haute couture. Guardian 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/dec/09/dressing-dakar-senegal-a-fashion-city-from-artisan-tailoring-to-haute-couture (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Embassy of India Dakar. The Textile Sector in Senegal and Business: Opportunities for Indian Industries; Embassy of India Dakar: Dakar, Senegal, 2019.

- Kobo, K. Why Senegal Is on Global Fashion’s Radar. 2022. Available online: https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/global-markets/why-senegal-is-on-the-global-fashion-radar/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Fenton, R. It Is Heritage: Two Families of Cloth Dyers in Dakar, Senegal. 2018. Available online: https://festival.si.edu/blog/it-is-heritage-two-families-cloth-dyers-dakar-senegal (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Guéguen-Teil, E. Traditional Textile Art: Tie Dye in West Africa. Elodie Travels 2018. Available online: https://elodietravels.wordpress.com/2018/02/03/traditional-textile-art-tie-dye-in-west-africa/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- UNEDO. Senegal Artisan Directory. 2013. Available online: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2009-03/Senegal_Artisan_Directory_0.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Valentine, S.V. The green onion: A corporate environmental strategy framework. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R.; Regnér, P.; Angwin, D. Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Whittington, R. Exploring Corporate Strategy; Amazon: Seattle, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy; Harvard Business Publishing: Brighton, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Aïssatou, N. Senegal Business Environment Update; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Samy, Y.; Adedeji, A.; Iraoya, A.; Dutta, M.K.; Fakmawii, J.L.; Hao, W. Trade and women’s economic empowerment: Qualitative analysis of SMEs from ghana, madagascar, nigeria, and senegal. In Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment: Evidence from Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 105–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, A. Political determinants of economic exchange: Evidence from a business experiment in Senegal. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2022, 66, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejkora, J.; Sankot, O. Comparative advantage, economic structure and growth: The case of Senegal. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, E.T.; Kelly, S. Policies and Institutions Shaping the Business Enabling Environment of Agrifood Processors in Senegal: An Analytical Review of the Literature for Integrated Policy Making; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wunu, P.; Züfle, S. Key success factors for promoting business to business collaboration. In Universities, Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development in Africa–Conference Proceedings; ResearchGate GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Shi, Z. Customer Satisfaction in the Fashion Industry: Case Study of HM Case Company. 2013. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:627836/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Niculescu, M.; Ghituleasa, C.; Mocioiu, A.M.; Nicula, G.; Surdu, L. Evaluations of formaldehyde emissions in clothing textiles. Romania 2013, 122, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Blckvanguard. The Story of the Last Textile Industry in Senegal. Available online: https://blckvanguard.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/the-story-of-the-last-textile-industry-in-senegal/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.; Wisneski, J.E.; Bakker, R.M. Strategy in 3D: Essential Tools to Diagnose, Decide, and Deliver; Amazon: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Harvard Business Publishing: Brighton, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, R. Strategic Management; Virginia Tech Publishing: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Tool/Method | Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| PESTEL analysis | Used to analyze the macro environment that the national and international environment share. It has no direct link with the organization, as it provides only broad societal trends. | [55,56] |

| Customer analysis | Customer analysis must often go beyond the examination of fundamental markets to include market segmentation—the study of particular market segments—and market positioning, or the evaluation of an organization’s competitive position within a segment. | [55] |

| Five Forces framework | According to the model, organizations face five forces that are aggressive to them. Porter’s Five Forces are what fuel industry rivalry. The goal of using the model is to leverage this to increase an organization’s competitive advantage so that it can outperform its competitors. | [55,57] |

| VRIO framework | The VRIO framework is a strategic planning tool that businesses can use to pinpoint specific assets and competencies that will give them a long-term competitive edge. | [55] |

| Value chain framework | This framework aids in the analysis of particular processes that businesses can use to generate value and a competitive edge. With the exception of manufacturing companies, it applies to all businesses. | [55] |

| SWOT analysis | SWOT summarizes the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that emerge from these analyses and are likely to have an impact on the development of strategies. This can also be a helpful starting point for developing strategic options and evaluating potential future directions for action. | [55] |

| TOWS analysis | TOWS is a strategic planning tool that enhances traditional SWOT analysis by translating insights into actionable strategies. This proactive approach encourages organizations to navigate industry challenges, optimize resource allocation, and achieve sustainable competitive advantage. It empowers organizations to formulate innovative strategies for long-term success. | [55] |

| Type of Segmentation | Description |

|---|---|

| Geographical | Divides the market into geographic divisions such as states, countries, regions, and cities. |

| Demographical | Market groups according to age, gender, size of family, life cycle of the family, education, income, nationality, generation, race, and religion |

| Psychographic | Divides customers into groups based on social class, lifestyle, and personal characteristics |

| Behavioral | The fundamental measurement standard for this segmentation is knowledge, attitude, and product responses. |

| Strength | Weakness |

|

|

| Opportunity | Threats |

|

|

| TOWS | Weakness | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Threat |

|

|

| Opportunities |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alzahmi, W.; Al-Assaf, K.; Alshaikh, R.; Al Khaffaf, I.; Ndiaye, M. Strategic Business Model Development for Sustainable Fashion Startups: Insights from the BANU Case in Senegal. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135722

Alzahmi W, Al-Assaf K, Alshaikh R, Al Khaffaf I, Ndiaye M. Strategic Business Model Development for Sustainable Fashion Startups: Insights from the BANU Case in Senegal. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135722

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlzahmi, Wadhah, Karam Al-Assaf, Ryan Alshaikh, Israa Al Khaffaf, and Malick Ndiaye. 2025. "Strategic Business Model Development for Sustainable Fashion Startups: Insights from the BANU Case in Senegal" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135722

APA StyleAlzahmi, W., Al-Assaf, K., Alshaikh, R., Al Khaffaf, I., & Ndiaye, M. (2025). Strategic Business Model Development for Sustainable Fashion Startups: Insights from the BANU Case in Senegal. Sustainability, 17(13), 5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135722