Understanding Ecotourism Decisions Through Dual-Process Theory: A Feature-Based Model from a Rural Region of Türkiye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

Perception Assessment Toward Ecotourism

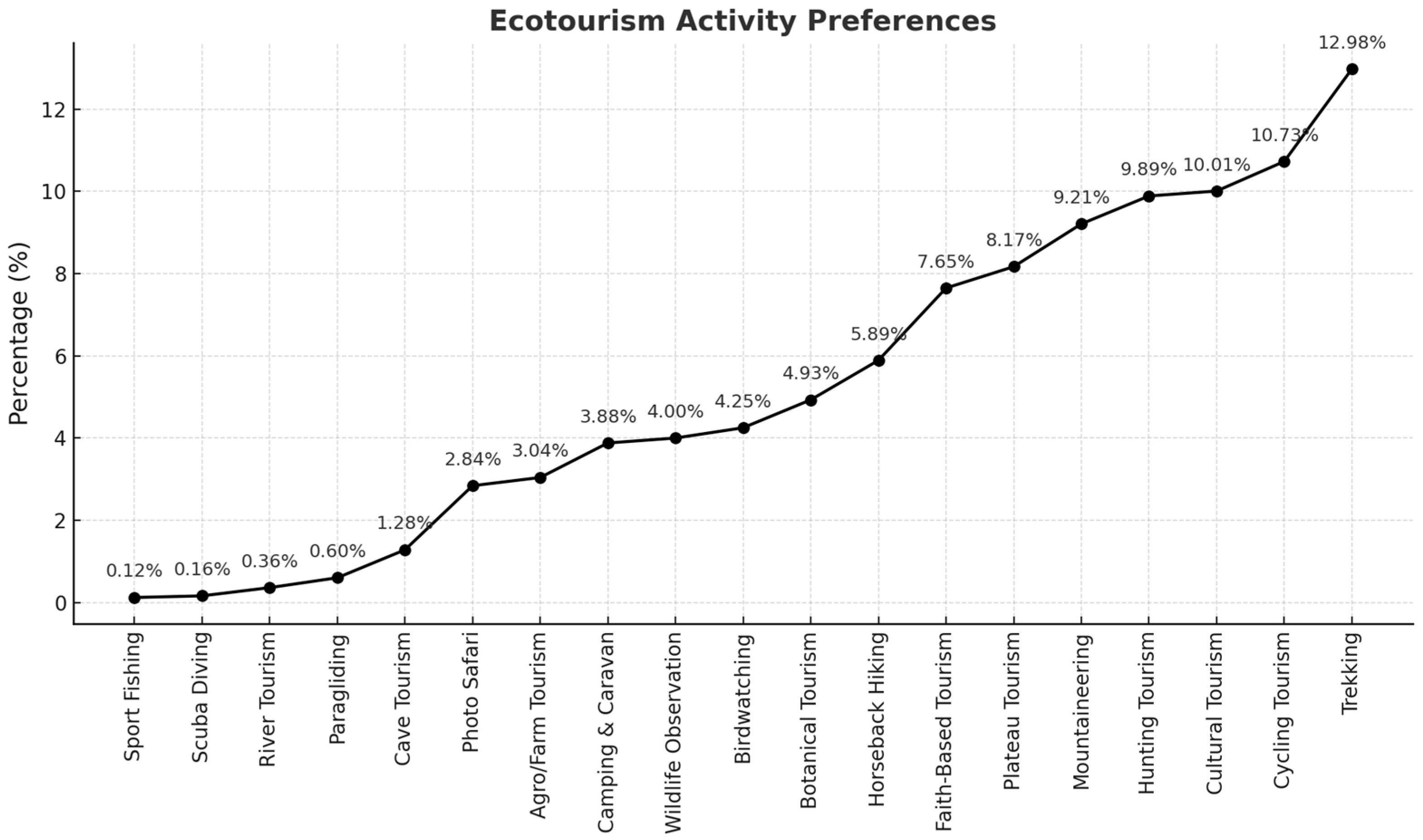

3.2. Ecotourism Activities Conducted

3.3. Cultural Tourism and Ecotourism Identity Values

3.3.1. Identity Values

3.3.2. Landscape Values

3.4. Evaluation of Attitudes Toward Ecotourism

3.4.1. Relationship Between Sociodemographic Questions and Ecotourism Attitudes

3.4.2. Ecotourism Perceptions and Ecotourism Attitudes

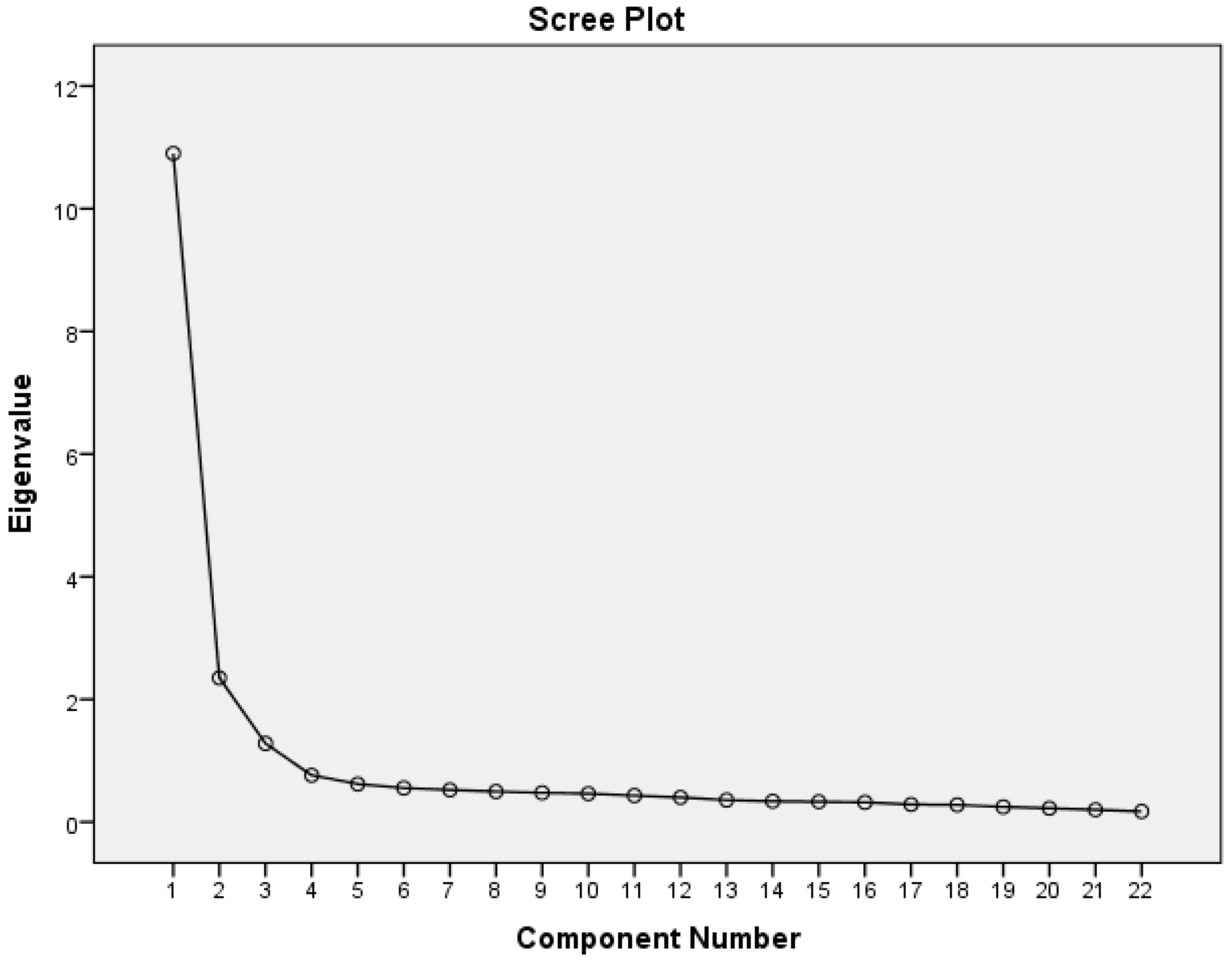

- ** Identity Value ** factor: This factor is represented by variables s9, s8, s7, s10, s6, s5, s1, and s14. Factor loadings vary between 0.720 and 0.823.

- ** Landscape Value ** factor: Variables sc8, sc6, sc2, sc11, sc10, sc9, sc4, sc1, and sc5 are grouped under this factor. Factor loadings vary between 0.648 and 0.743.

- ** Ecotourism Attitude ** factor: Variables s20, s18, s16, s17, and s22 are grouped under this factor. Factor loadings vary between 0.699 and 0.760.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afenyo, E.A.; Amuquandoh, F.E. Who Benefits from Community-based Ecotourism Development? Insights from Tafi Atome, Ghana. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, V.C.; Thompson, W. Assessing community support and sustainability for ecotourism development. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.B. Eco-destination image, environment beliefs, ecotourism attitudes, and ecotourism intention: The moderating role of biospheric values. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Song, J.; Yang, L.; Zhong, L.; Yan, K. Ecotourism certification and regional low-carbon sustainable development: A quasi-experimental study based on the prototype-zone of national ecotourism attractions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.C.C.; Gursoy, D.; Del Chiappa, G. The influence of materialism on ecotourism attitudes and behaviors. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, M. Use energy efficiency, eco-design, and eco-friendly materials to support eco-tourism. J. Power Energy Eng. 2019, 7, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.L.; Marzuki, K.M.; Mohtar, T.M. Local community participation and responsible tourism practices in ecotourism destination: A case of lower Kinabatangan, Sabah. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, F.; Jamshidi, M.J.; Mohammadifar, Y. A model to develop the ecotourism industry in Iran with emphasis on information technology. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 11, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Almasifar, N.; Mehbodniya, A.; Javaheri, D.; Webber, J. Towards green smart cities using Internet of Things and optimization algorithms: A systematic and bibliometric review. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 36, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z. Booking now or later: Do online peer reviews matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unlu, B.Ç. Analyzing Sustainable Tourism Development in Mass Tourism Destinations from the Perspective of Social Representation Theory: Antalya Example. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Social Sciences, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pookhao, N.; Bushell, R.; Hawkins, M.; Staiff, R. Community-Based Ecotourism: Beyond Authenticity and the Commodification of Local People. J. Ecotour. 2018, 17, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Moreno, M.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Approaches, Trends, and Gaps in Community-Based Ecotourism Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications between 2002 and 2022. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çavuşoğlu, M. Bozcaada Grape Farming Tourism and Electronic Tourism Design Site Application. Int. J. Soc. Econ. Sci. 2009, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D. Comprehensive and Minimalist Dimensions of Ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülgün, B.; Yazici, K.; Ankaya, F. Ecotourism in Turkey from Past to Present and the Scientific Awareness. Karabuk Univ. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, K. Challenges of Sustaınable Ecotourısm And Envıronmental Impacts Akdagmadenı Case Turkıye. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2024, 25, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Bonn, M. Can the value-attitude-behavior model and personality predict international tourists’ biosecurity practice during the pandemic? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülgün, B.; Yazici, K.; Dikmen, A.; Dursun, Ş. Ecotourism Importance of Sumela Monastery in Trabzon, Turkey. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2014, 12, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Helen, M.B. Tourism challenges and the opportunities for sustainability: A case study of Grenada, Barbados, and Tobago. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 3, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Application and development of big data, internet of things, and cloud computing in tourism and its influence on traditional travel agencies. In Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research; Atlantis Press International B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 3291–3295. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, Y. Evaluation of Erdek and Its Surroundings in Terms of Ecotourism. J. Balikesir Univ. Soc. Sci. Inst. 2005, 8, 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Paydar, M.M.; Triki, C. Implementing sustainable ecotourism in Lafour region, Iran: Applying a clustering method based on SWOT analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanyan, S.; Shafiee, S.; Ghatari, A.; Hasanzadeh, A. Smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 505–528. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, M.; Popescu, A.; Sava, C.; Moise, G.; Nistoreanu, B.G.; Rodzik, J.; Bratu, I.A. Youth’s perception toward ecotourism as a possible model for sustainable use of local tourism resources. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, A.; Ewane, E.B.; McTavish, F.; Watt, M.S.; Rogers, K.; Daneil, R.; Vizcaino, I.; Gomez, A.N.; Arachchige, P.S.P.; King, S.A.L. Ecotourism and Mangrove Conservation in Southeast Asia: Current Trends and Perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.E.; Rosen, C.C.; Djurdjevic, E. Assessing the impact of common method variance on higher order multidimensional constructs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitti, M.; Pilloni, V.; Giusto, D.; Popescu, V. IoT architecture for a sustainable tourism application in a smart city environment. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenow, S.; Pimenowa, O.; Prus, P.; Nikla, A. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Sustainability of Regional Ecosystems: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, B. Exploring the nexus of smart technologies and sustainable ecotourism: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.H.; Vogt, C. Travel Information Processing Applying A Dual-Process Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.; Sperry, T. Interocular transfer of the visual form discrimination habit in cats after section of the optic chiasma and corpus callosum. Anat. Rec. 1953, 175, 351–352. [Google Scholar]

- Solso, R.L.; MacLin, M.K.; MacLin, O. Cognitive Psychology, 5th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç Benzer, N.A. Evaluation of Natural and Cultural Resources of Bolu-Göynük and Its Surroundings in Terms of Ecotourism. PhD Thesis, Institute of Science, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, A.; Önder, S. A Study on the Evaluation of Landscape Features of Karapınar District and Its Surroundings in Terms of Ecotourism Use. J. Fac. Agric. 2006, 20, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Soykök Ede, B.; Taş, M.; Taş, N. Sustainable Management of Rural Architectural Heritage Through Rural Tourism: Iznik (Turkey) Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panin, B.; Mbrica, A. Potentials of Ecotourism As A Rural Development Tool based on Motivation Factors İn Serbia. 2014. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130226729 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Ekiz, G. Evaluation of Landscape Corridors within the Scope of Ecotourism Planning: Belemedik Nature Park—Kapıkaya Canyon Example. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Science, Çukurova University, Adana, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, O. The Role of Ecotourism in Conservation: Panacea or Pandora’s Box? Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrianto, Y. Mangrove Forest Utilization for Sustainable Livelihood Through Community-Based Ecotourism in Kao Village of North Halmahera District. J. Manaj. Hutan Trop. 2020, 26, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jang, S.C. Understanding beach tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviors: An extended value-attitude-behavior model. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirahayu, Y.; Sumarmi, S.; Arinta, D.; Islam, M.; Kurniawati, E. Developing a Sustainable Community Forest-Based Village Ecotourism in Oro-Oro Ombo, Malang: What is the Effect of Batu’s West Ring Road? J. Dev. Tour. 2022, 39, 425–437. [Google Scholar]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Wall, G. Ecotourism: Towards Congruence Between Theory and Practice. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, F.; Ghobadi, G.R.J. The Role of Ecotourism Potentials İn Ecological and Environmental Sustainable Development of Miankaleh Protected Region. Open J. Geol. 2017, 7, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaano, A.I. Potential of Ecotourism As a Mechanism toBuoy Community Livelihoods: The Case of Musina Municipality, Limpopo, South Africa. J. Bus. Socio-Econ. Dev. 2021, 1, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargahov, V.S.; Mammadov, Q.V.; Nuriyeva, I.F.; Ahmadov, R.I. Prospects ofUsing the Tourism Potential of the Liberated Territories from The Point of View ofEcotourism. J. Geol. Geogr. Geoecology 2023, 32, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervankıran, İ.; Temurçin, K. Approaches of local people towards ecotourism in Afyonkarahisar Province. In Geographers Association Annual Congress Proceedings Book; Fatih University: Istanbul, Turkey, 2013; pp. 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Sayın, K. A Study in Taşucu to Determine the Perceptions of Local People Regarding the Contribution of Ecotourism to Local Development. Gastron. Hosp. Travel J. 2022, 5, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bakır Ertaş, V. The Effect of Ecotourism Awareness of Şırnak People on Ecotourism Perception. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Graduate Education, Şırnak University, Şırnak, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, K.; Aşur, F. Assessment of Landscape Types and Aesthetic Qualities by Visual Preferences Tokat Turkey. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2021, 22, 340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Aşur, F.; Sevimli Deniz, S.; Yazici, K. Visual Preferences Assessment of Landscape Character Types Using Data Mining Methods Apriori Algorithm TheCase of Altınsaç and Inkoy Van Turkey. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2020, 22, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Oğuz, C.; Karakayacı, Z. Research and Sampling Methodology in Agricultural Economics; Atlas Academy: Konya, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R.; Bartholdi, E.; Ernst, R.R. Diffusion and field-gradient effects in NMR Fourier spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 1974 2017, 60, 2966–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9781292021904. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Leavitt, C. Audience involvement in advertising: Four Levels. J. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.; Cacioppo, J.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S.; Pacini, R.; Denes-Raj, V.; Heier, H. Individual differences in intuitive-experiential and analytical-rational thinking styles. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.; Hoffman, D. The fit of thinking style and situation: New measures of situation-specific experiential and rational cognition. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; De Coster, J. Dual-process models in social and cognitive psychology: Conceptual integration and links to underlying memory systems. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 4, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, D.; Bahar, M. Evaluation of local people’s perception towards ecotourism: Isparta example. Int. J. Econ. Innov. 2020, 6, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Tourism that describes nature and gives the opportunity to spend time in nature. | 26.9% |

| Tourism that offers an expensive and fashionable trip. | 7.1% |

| Tourism provides an escape from stress and relaxation. | 19.7% |

| It is a tourism where I can realize my sporting activities. | 18.5% |

| Tourism that helps local development. | 17.5% |

| Tourism that includes tours and activities related to nature. | 10.3% |

| Category | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Local governments are not creating policies on this issue. | 28.13% |

| Lack of sufficient promotion to local people. | 20.83% |

| The public’s unawareness of/insensitivity to ecotourism. | 23.90% |

| Lack of sufficient directions and signs. | 17.85% |

| Lack of sufficient ecotourism potential in Akdağmadeni. | 9.29% |

| Identity Value | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Muşali Behramşah Castle | 4.81 | 0.60 |

| Old Church | 4.51 | 0.65 |

| Akdağmadeni Salebi | 4.71 | 0.63 |

| Göbelek Mushroom (Kuzu Göbeği-in Turkish) | 4.55 | 0.69 |

| Old PTT Building | 4.57 | 0.68 |

| Old Military Service Building | 4.60 | 0.72 |

| Old Prison Building | 4.58 | 0.70 |

| Old Public Education Center Building | 4.61 | 0.69 |

| Old Industrial Vocational High School Building | 4.59 | 0.72 |

| Old Ziraat Bank Building | 4.63 | 0.71 |

| Hami Tüzün Shops | 4.31 | 0.79 |

| Old High School Building (Redif Barracks) | 4.30 | 0.88 |

| Rıfat Koç Mansion | 2.93 | 1.39 |

| İstanbulluoğlu Neighborhood Mosque | 4.69 | 0.67 |

| Landscape Value | ||

| Kadıpınarı Nature Park | 4.85 | 0.56 |

| Akdağmadeni Yellow Pine Forests | 4.64 | 0.66 |

| Göndelen Valley | 4.79 | 0.61 |

| Çerçialanı Village Pond | 4.75 | 0.62 |

| Horse Gutter Fountain | 4.32 | 0.75 |

| Nalbant Plateau | 4.65 | 0.65 |

| Küçük Kefenli Plateau | 3.95 | 0.98 |

| Hisarbey Plateau | 4.56 | 0.70 |

| Value | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Ecotourism creates new job opportunities for local people. | 4.82 | 0.63 |

| 2. The development of ecotourism can improve the economic situation of the region. | 4.27 | 0.64 |

| 3. Ecotourism increases the purchasing power and quality of life of local people. | 4.45 | 0.79 |

| 4. Ecotourism promotes and supports the development of the region where it is practiced. | 4.52 | 0.68 |

| 5. Ecotourism accelerates the urbanization of rural areas. | 4.39 | 0.80 |

| 6. Ecotourism contributes to the promotion of different cultures. | 4.52 | 0.71 |

| 7. Ecotourism helps protect nature and the environment. | 4.51 | 0.79 |

| 8. Ecotourism contributes to the development of commercial activities in the region. | 4.55 | 0.67 |

| 9. Ecotourism contributes to the protection of historical and cultural heritage. | 4.51 | 0.75 |

| 10. Ecotourism acts as a bridge in recognizing different cultures. | 4.57 | 0.68 |

| 11. Ecotourism enables tourists and local people to interact. | 4.59 | 0.68 |

| 12. Promotion of the region in terms of ecotourism is sufficient. | 4.08 | 0.90 |

| 13. Local governments carry out important activities for the development and promotion of ecotourism. | 3.54 | 1.39 |

| KMO versus Bartlett’s Test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.953 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 5,838,117 |

| df | 231 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| Category | Initial Eigenvalues | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Varyans Percentage (%) | Cumulative % | Total | Varyans Percentage (%) | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 10,902 | 49,554 | 49,554 | 5704 | 25,928 | 25,928 |

| 2 | 2349 | 10,679 | 60,233 | 5314 | 24,155 | 50,083 |

| 3 | 1280 | 5817 | 66,049 | 3513 | 15,966 | 66,049 |

| 4 | … | … | … | |||

| 5 | … | … | … | |||

| 22 | 0.172 | 0.781 | 100,000 | |||

| Rotated Component Matrix a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| IDENTITY VALUE | Old Building of Industrial Vocational High School | 0.823 | ||

| Old Building of Public Education Center | 0.796 | |||

| Old Prison Building | 0.783 | |||

| Old Building of Ziraat Bank | 0.771 | |||

| Old Building of the Military Service Office | 0.766 | |||

| Old Building of PTT | 0.759 | |||

| Muşali Behramşah Castle | 0.731 | |||

| İstanbulluoğlu Neighborhood Mosque | 0.720 | |||

| LANDSCAPE VALUE | Ecotourism contributes to the development of existing commercial activities in the region. | 0.743 | ||

| Ecotourism contributes to the promotion of different cultures. | 0.737 | |||

| The development of ecotourism can improve the economic situation of the region. | 0.735 | |||

| Ecotourism enables tourists and local people to interact. | 0.734 | |||

| Ecotourism acts as a bridge for the recognition of different cultures. | 0.715 | |||

| Ecotourism contributes to the protection of historical and cultural heritage. | 0.715 | |||

| ECOTOURISM ATTITUDE | Ecotourism promotes and supports the development of the region where it is practiced. | 0.696 | ||

| Ecotourism creates new business opportunities for local people. | 0.651 | |||

| Ecotourism accelerates the urbanization of rural areas. | 0.648 | |||

| Nalbant Plateau | 0.760 | |||

| Çerçialanı Village Pond | 0.724 | |||

| Akdağmadeni Yellow Pine Forests | 0.717 | |||

| Göndelen Valley | 0.716 | |||

| Hisarbey Plateau | 0.699 | |||

| Extraction method: principal component analysis Rotation method: varimax with kaiser normalization | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karaman, K. Understanding Ecotourism Decisions Through Dual-Process Theory: A Feature-Based Model from a Rural Region of Türkiye. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135701

Karaman K. Understanding Ecotourism Decisions Through Dual-Process Theory: A Feature-Based Model from a Rural Region of Türkiye. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135701

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaraman, Kübra. 2025. "Understanding Ecotourism Decisions Through Dual-Process Theory: A Feature-Based Model from a Rural Region of Türkiye" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135701

APA StyleKaraman, K. (2025). Understanding Ecotourism Decisions Through Dual-Process Theory: A Feature-Based Model from a Rural Region of Türkiye. Sustainability, 17(13), 5701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135701