Classification of Hiking Difficulty Levels of Accessible Natural Trails

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formulation of Research Questions

- Context (where?)

- Intervention (what?)

- Mechanism (how?)

- Result (to achieve what?)

- How to design (M) interventions on paths and trails (I) in nature (C) to make them accessible to people with motor impairments (O)?

- What conditions (I) can improve the accessibility (O) of outdoor trails (C) for people with motor disabilities?

- access* (access, accessible, accessibility)

- AND nature* OR outdoor OR park*

- AND wheelchair* OR “mobility aid*”

- AND disable* OR disability* OR impairment*

2.2. Application of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Context: Different natural sites such as parks, urban forests, outdoor recreation sites, and trails, where natural elements are more prevalent than man-made ones. Studies where outdoor environments are more man-made than natural, such as roads and sidewalks, were excluded.

- Participants: Individuals of all ages with motor disabilities were identified as our target group. Motor disabilities are very common among the elderly and in families with young children. Therefore, studies whose target groups were elderly or were focused on motor disabilities and parents with children in strollers were also considered eligible. The decision to include studies on other target groups and other levels of disability was based on the content of the study.

- Accessibility issues: We took into consideration only those accessibility issues related to outdoor activities that led to a better use of trails and outdoor recreation areas with scientific and reasonable solutions. Barriers found in enclosed spaces, man-made roads, and transportation infrastructures were not included in our scope.

2.3. Documents Found Through Other Searches

- Aids for accessing the routes (independently and with assistance).

- Trail classifications for PwDs.

- Trail accessibility guidelines.

- Local complementary services.

3. Results

3.1. Aids to Be Used Independently

- Rigid frame wheelchair: characterised by a fixed and non-folding frame, which guarantees greater rigidity and stability. This model is generally lighter, which makes it easier to use for people who have good self-propulsion abilities. Ease of handling and movement are two of its main advantages.

- Folding wheelchair: equipped with a mechanism that allows the frame to be folded, making it easier to transport and store. However, compared to rigid-frame wheelchairs, these wheelchairs tend to be heavier and may be slightly less responsive in movement due to the greater flexibility of the frame.

3.1.1. Small Wheel for Wheelchairs

3.1.2. Off-Road Wheels

3.1.3. Auxiliary Drives

- Voltage, unique parameter for battery and motor, measured in Volts [V].

- Power, speed at which a motor can make a movement, measured in Watts [W].

- Torque, rotational force that an engine can impart, measured in Newton-metre [Nm].

- Tyre diameter and width, measured in Inches [″].

- IBS—Intelligent Braking System: Fully electronic braking system, with programmable and customizable intensity. Anti-slip system and battery charging during braking.

- ICC—Intelligent Cruise Control: In addition to the normal Cruise Control function, it allows for maintaining the set speed even when going downhill, adapting to changes in slope, without requiring the use of the brake.

- MDC—Motion Direct Control: Electronic traction control system (speed control). With just one command (accelerator) the user has a total control over the movement of the device and its pace.

- Eco Drive System: It acts on the delivery of the maximum power of the device with five programmable and customizable levels.

3.1.4. Rear Drive Kit for Wheelchairs

3.2. Aids to Be Used with Assistance

3.2.1. Joëlette

3.2.2. Emerging Technologies: Smart Wheelchairs and IoT Devices

3.3. Trail Classification for PwDs

3.3.1. Trail Classification for Self-Propelled Wheelchair

- easy: slopes ≤ 5%, mobility with little or no assistance required;

- moderate: slopes > 5% (with resting spots every 5 m), mobility may require assistance;

- most difficult: slopes ≥ 5%, mobility will require assistance.

- easy: slopes ≤5 %, mobility with little or no assistance required;

- moderate: gradients of 5–8.33%, mobility may require assistance;

- difficult: gradients of 8.33–10%, mobility may require assistance;

- most difficult: slopes ≥ 10%, mobility will require assistance.

- easy: slopes ≤ 5.50%, mobility with little or no assistance required;

- moderate: gradients of 5.5–9%, mobility may require assistance;

- most difficult: slopes ≥ 9.01%, mobility will require assistance.

3.3.2. Club Alpino Italiano—Classification of Accessible Mountain Routes

- T = Tourist. Paths that develop on small roads, mule tracks or comfortable trails, with altitude differences of less than 500 m. These hikes do not require particular experience or physical preparation.

- E = Hiker. Paths that almost always take place on trails with altitude differences between 500 and 1000 m. They require training in walking, as well as suitable footwear and equipment.

- EE = Experienced Hiker. Paths that require a good ability to move through impervious or steep terrain, with altitude differences normally greater than 1000 m. They require good hiking experience and good physical preparation, as well as adequate equipment and gear.

- EEA = Experienced Hiker with Mountaineering Equipment. Paths that require the use of via ferrata equipment (ropes, harness, lanyard, helmet, etc.). They can be equipped trails or real via ferratas. It is necessary to know how to use technical equipment safely and to have some familiarity with exposure and mountaineering terrain.

- Type of route (trail, mule track, etc.). These are standardised, well described and recognisable categories.

- Main features (based on the users): slope, width, difference in altitude, length. Always considered not in general or abstract terms, but specifically observed in relation to the users of the scale.

- Evidence of actual problems: terrain viability, obstacles, problematic points for manoeuvring, and/or exposure. This information is specific for the user/assistant.

- Notes that complete and characterise the whole picture. These are essential to better parametrize the Scale and add information without changing the Scale itself.

- AT = Accessible for Tourists. Routes on dirt tracks or grassy tracks. They are characterised by modest slopes (less than 8%), width greater than 1.5 metres, limited differences in height (less than 150 metres), and length less than 3 km. They generally have a smooth and flowing surface, without artificial or natural steps, without exposed points or tight curves that could make manoeuvring difficult.Notes: Although it is possible to overcome small slopes (up to 4 ÷ 5%) independently with a self-propelled wheelchair, it is not advisable to go on mountain routes alone.

- AE = Accessible for Hikers. Routes on clear paths and cobbled mule tracks. They are characterised by moderate slopes (less than 16%), width between one metre and one and a half metres differences in altitude of less than 300 metres, length from 3 to 6 km, uneven surface, few and/or modest artificial or natural steps that can be easily overcome by an off-road auxiliary device, absence of significant obstacles, absence of exposed points and/or tight curves that could make manoeuvring difficult.Notes: Regardless of the length of the route, it is necessary to consider the time required to complete the hike in relation to potential issues in the passenger’s permanence on the seat of the aid.

- AEE = Accessible for Experienced Hikers. Routes on mule tracks and paths with traces of passages in varied terrain. They are characterised by some sections with gradients of more than 16%, a width of less than one metre, differences in altitude greater than 300 metres, a length greater than 6 km, a surface that is sometimes uneven and leads to forced passages, natural or artificial steps taller than 10 centimetres, significant obstacles, exposed points and/or tight bends.Notes: the presence of at least one of these features makes the route classifiable as AAE, since it requires skills, techniques, experience, and a crew size adequate to overcome the reported difficulties. Regardless of the length of the route, it is necessary to consider the time required to complete the hike in relation to potential issues in the passenger’s permanence on the seat of the aid.

3.3.3. Schweiz Mobil/Svizzera Mobile—Difficulty Levels for “Barrier-Free Routes”

3.4. Synthesis of a Comprehensive Difficulty Levels Classification for Accessible Hiking Trails

3.5. Guidelines for Accessible Outdoor Services

Design for All aims to enable all people to have equal opportunities to participate in every aspect of society. To achieve this goal, the built environment, everyday objects, services, culture, and information—in short, everything that is designed and made by people to be used by people—must be accessible, convenient for everyone in society to use and responsive to evolving human diversity.

- Equity, intended as designing for all, regardless of disabling conditions.

- Flexibility, intended as the ability to adapt to different disabling conditions.

- Simplicity and intuitiveness, consisting in the ease of understanding regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, linguistic skills or level of concentration.

- Information perceptibility, consisting in the effective communication of necessary information to the user, regardless of environmental conditions or sensory capabilities.

- Tolerance for error, consisting in the minimization of dangers and adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Reduction in physical effort, consisting in using the design efficiently, comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use, consisting in making the space easily usable regardless of the user’s body size, posture, and abilities.

- “Urban and formal landscapes”, e.g., countryside areas with many man-made features;

- “Urban fringe and managed landscapes”, e.g., countryside areas near towns or outdoor recreation areas;

- “Rural and working landscapes”, e.g., farmland and woodland;

- “Open Country, semi-wild and wild”, e.g., mountains, moorlands, and remote countryside.

3.6. Inclusive Planning and Local Services

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, R.; Sibi, P.S.; Yost, E.; Mann, D.S. Tourism and Disability: A Bibliometric Review. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Diekmann, A. The Rights to Tourism: Reflections on Social Tourism and Human Rights. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, A.F.A.; Kastenholz, E.; Pereira, A.M.S. Accessible Tourism and Its Benefits for Coping with Stress. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2018, 10, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Alves, J.P.; Carneiro, M.J.; Teixeira, L. Needs, Motivations, Constraints and Benefits of People with Disabilities Participating in Tourism Activities: The View of Formal Caregivers. Ann. Leis. Res. 2024, 27, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyk, M.; Suchocka, M.; Wojnowska-Heciak, M.; Muszyńska, M. Quality of Urban Parks in the Perception of City Residents with Mobility Difficulties. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Poulsen, D.; Lygum, V.; Corazon, S.; Gramkow, M.; Stigsdotter, U. Health-Promoting Nature Access for People with Mobility Impairments: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Huang, R.; Zhang, J.U.S. National Parks Accessibility and Visitation. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 2894–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowiński, R.; Morgulec-Adamowicz, N.; Ogonowska-Slodownik, A.; Dąbrowski, A.; Geigle, P.R. Participation in Leisure Activities and Tourism among Older People with and without Disabilities in Poland. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 73, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Jakubisová, M.; Woźnicka, M.; Fialova, J.; Kotásková, P. Preferences of People with Disabilities on Wheelchairs in Relation to Forest Trails for Recreational in Selected European Countries. Folia For. Pol. 2016, 58, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Baronio, G.; Copeta, A.; Motyl, B.; Uberti, S. Gölem Project: Concept and Design of a Trekking/Hiking Wheelchair. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 168781401773054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronio, G.; Bodini, I.; Motyl, B.; Uberti, S. Prototyping, Testing, and Redesign of a Three-Wheel Trekking Wheelchair for Accessible Tourism Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreevatsav, S.; Sheth, S.; Kumar, A.; Dwivedy, B. An IoT Enabled Smart Wheelchair Solution for Physically Challenged People. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Vision Towards Emerging Trends in Communication and Networking Technologies (ViTECoN), Vellore, India, 5–6 May 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, P.; Cappelletti, G.M.; Mafrolla, E.; Sica, E.; Sisto, R. Accessible Tourism in Natural Park Areas: A Social Network Analysis to Discard Barriers and Provide Information for People with Disabilities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S.; Gramkow, M.C.; Poulsen, D.V.; Lygum, V.L.; Zhang, G.; Stigsdotter, U.K. I Would Really like to Visit the Forest, but It Is Just Too Difficult: A Qualitative Study on Mobility Disability and Green Spaces. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, K.G.; Ioannides, D. Enhancing Accessibility in Tourism & Outdoor Recreation: A Review of Major Research Themes and a Glance at Best Practice; Mid Sweden University: Östersund, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldma, T.; Carbonneau, H.; Miaux, S.; Mazer, B.; Le Dorze, G.; Gilbert, A.; Hammouni, Z.; El-Khatib, A. Lived Experiences and Technology in the Design of Urban Nature Parks for Accessibility. In Universal Access in Human–Computer Interaction. Human and Technological Environments; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10279, pp. 308–319. ISBN 978-3-319-58699-1. [Google Scholar]

- Agovino, M.; Casaccia, M.; Garofalo, A.; Marchesano, K. Tourism and Disability in Italy. Limits Oppor. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialová, J.; Kotásková, P.; Schneider, J.; Žmolíková, N.; Procházková, P. Geo-Caching for Wheelchair Users: A Pilot Study in Luhačovské Zálesí (Czech Republic). Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, Y. Access to the Forests for Disabled People; National Board of Forestry: Jönköping, Sweden, 2005; Available online: https://cdn.abicart.com/shop/9098/art29/4646029-705d4d-1678.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Zeller, J.; Doyle, R.; Snodgrass, K. Accessibility Guidebook for Outdoor Recreation and Trails; USDA Forest Service, Missoula Technology and Development Center: Missoula, MT, USA, 2012; pp. 1–133. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/t-d/pubs/pdfpubs/pdf12232806P/pdf12232806dpi300.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Lepoglavec, K.; Papeš, O.; Lovrić, V.; Raspudić, A.; Nevečerel, H. Accessibility of Urban Forests and Parks for People with Disabilities in Wheelchairs, Considering the Surface and Longitudinal Slope of the Trails. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joëlette and Co. Available online: https://www.joeletteandco.com/en/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Wall-Reinius, S.; Kling, K.G.; Ioannides, D. Access to Nature for Persons with Disabilities: Perspectives and Practices of Swedish Tourism Providers. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groulx, M.; Lemieux, C.; Freeman, S.; Cameron, J.; Wright, P.A.; Healy, T. Participatory Planning for the Future of Accessible Nature. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldfare Trust Ltd. Countryside for All. Good Practice Guide: A Guide to Disabled People’s Access in the Countryside. Scotland. 2005. Available online: https://www.pathsforall.org.uk/mediaLibrary/other/english/countryside-for-all-guide.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- National Confederation of Disabled People of Greece. Guidebook for Accessible Nature Trails: Design Guidelines and Evaluation System 2019. Greece. 2019. Available online: https://accessible-eu-centre.ec.europa.eu/content-corner/digital-library/guidebook-accessible-nature-trails-design-guidelines-and-evaluation-system_en (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Irish Wheelchair Association; Sport Ireland. Great Outdoors—A Guide for Accessibility. Ireland. 2018. Available online: https://www.sportireland.ie/sites/default/files/2019-10/great-outdoors-a-guide-for-accessibility.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D.; Van Aken, J.E. Developing Design Propositions through Research Synthesis. Organ. Stud. 2008, 29, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Khusaini, N.S.; Mohamed, Z.; Hamid, A.; Yusof, Y.; Aziz, M.R. Smart Wheelchairs: A Review on Control Methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Engineering and Technology (IICAIET), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 13 September 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Bottone, E.; Lee, M. Beyond Accessibility: Exploring the Representation of People with Disabilities in Tourism Promotional Materials. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikuta, O.; Du Plessis, E.; Saayman, M. Accessibility Expectations of Tourists with Disabilities in National Parks. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloquet, I.; Palomino, M.; Shaw, G.; Stephen, G.; Taylor, T. Disability, Social Inclusion and the Marketing of Tourist Attractions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Club Alpino Italiano. Classificazione dei Percorsi Montani Accessibili con Ausili. Available online: https://archivio.cai.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Documento-Percorsi-Accessibili-con-Loghi-2021.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Darcy, S.; Cameron, B.; Pegg, S. Accessible Tourism and Sustainability: A Discussion and Case Study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fennell, D.A. Strategic Approaches to Accessible Ecotourism: Small Steps, the Domino Effect and Not Paving Paradise. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaman, J.; La, H.M. A Comprehensive Review of Smart Wheelchairs: Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Trans. Human-Mach. Syst. 2017, 47, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukerkar, K.; Suratwala, D.; Saravade, A.; Patil, J.; D’britto, R. Smart Wheelchair: A Literature Review. Int. J. Inform. Commun. Technol. 2018, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svizzera Mobile, Obstacle-Free Routes, Grade of Difficulty. Available online: https://www.procap-voyages.ch/fileadmin/files/RSF_Reisen_Sport_Freizeit/freizeit/Downloads/Barrierefreie_Wanderwege/Francais/20200101_die_Schwierigkeitsgrade_Hindernisfreie_Wege_fr.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- FreeWheel, Wheelchair Attachment. Available online: https://www.gofreewheel.com/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Offcar, EasyWheel. Available online: https://www.offcarr.com/prodotto/accessorio-carrozzina-easywheel/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Batec Mobility. Available online: https://batec-mobility.com/en/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Klaxon Mobility. Available online: https://www.klaxon-klick.com (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Triride. Available online: https://www.trirideitalia.com/en/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Triride, Trekking Power. Available online: https://www.trirideitalia.com/en/mtw-multi-traction-wheelchair/mtw-trekking-power/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Joëlette and Co, Joëlette Emotion. Available online: https://www.joeletteandco.com/en/project/joelette-emotion-en/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- TrailRider. Available online: https://bcmos.org/trailrider/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Offcar, K-Bike. Available online: https://www.offcarr.com/prodotto/k-bike-easytrekking/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Joëlette and Co, Instruction Manual. Available online: https://www.joeletteandco.com/wp-content/uploads/Notice-Joelette-Adventure-eMotion-AN.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Italy. Law No. 776 of 24 December 1985. New Provisions on the Italian Alpine Club. Gazzetta Ufficiale No. 305. 30 December 1985. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/1985/12/30/305/sg/pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Club Alpino Italiano. Available online: https://www.cai.it/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Club Alpino Italiano. Classificazione dei Percorsi in Base Alla Difficoltà in Ambito Escursionistico e Cicloescursionistico. Available online: https://archivio.cai.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Classificazione-difficolta-CAI.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Giordana, M.O.; Battain, M. Montagne360. pp. 14–15. Available online: https://issuu.com/cai-clubalpinoitaliano/docs/montagne360-settembre2021 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Perovani Vicari, A. Montagne360. pp. 24–25. Available online: https://issuu.com/cai-clubalpinoitaliano/docs/montagne360-settembre2021 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Schweizer Wanderwege/Sentieri Svizzeri. Available online: https://www.sentieri-svizzeri.ch (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- SchweizMobil/SvizzeraMobile. Available online: https://schweizmobil.ch (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Offerte Senza Barriere, SvizzeraMobile. Available online: https://schweizmobil.ch/it/offerte-senza-barriere (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Procap Switzerland. Available online: https://www.procap.ch/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Mace, R.L. Universal Design: Barrier Free Environments for Everyone; Mississippi State University Libraries: Mississippi State, MS, USA, 1985; pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Design and Disability (EIDD). The EIDD Stockholm Declaration. Sweden. 2004. Available online: https://dfaeurope.eu/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/stockholm-declaration_english.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- EN 17210:2021; Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment—Functional Requirements. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- ISO 21542:2011; Building Construction—Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

| Context | Intervention | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where? In which context the intervention is conducted | What? What is the main topic | How? What are the means | To get what? What is the wanted information |

| Nature | Interventions on routes/paths | Design | Accessibility for people with motor disabilities |

| Mountain | Tread Obstacles | Universal Design | Access |

| Park | Route Surfaces | Inclusive Design | Accessible |

| Forest | Gates and Barriers | Health Design | Accessibility |

| Wood | Slope | Design for all | Adaptive |

| Path | Wheelchair | Interventions | Disability |

| Route | Aid | Planning | Motor disability |

| Trail | Mobility aids | Barrier-free | People with Motor Impairments |

| Trekking | Support | Guidelines | People with physical disabilities |

| Hiking | Design | ||

| Outdoor | Universal Design | ||

| Open space | Inclusive Design |

| Authors (Country) | Title (Document Type) | Problem Statement— Purpose | Methodological Philosophy | Research Methods— Specifics | Findings— Results | Unsolved Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agovino M.; Casaccia M.; Garofalo A.; Marchesano K. 2017 (Italy) [18] | Tourism and disability in Italy. Limits and opportunities (Article) | Tourism demand of PwDs. Factors that hinder or encourage participation | Qualitative | Secondary data from Italian sources | Significant tourism segment with growing demand | Many limitations hinder the development of accessible offering |

| Aziz, N.; Khusaini, N.S.; Mohamed, Z.; Hamid, A.; Yusof, Y.; Aziz, M.R. 2022 (Malaysia) [30] | Smart Wheelchairs: A Review on Control Methods (Conference paper) | Examines smart wheelchair control methods, emphasising advancements in AI, sensors, and user interfaces | Qualitative | Literature Review | Advancements in smart wheelchair control methods, focusing on AI, robotics, and sensor integration | Limited autonomous navigation, sensor reliability, cost and accessibility |

| Baronio, G.; Bodini, I.; Motyl, B.; Uberti, S. 2021 (Italy) [12] | Prototyping, Testing, and Redesign of a Three-Wheel Trekking Wheelchair for Accessible Tourism Applications (Article) | Validating by testing the prototype of a trekking wheelchair for PwDs | Qualitative | Data on stability, effort required for handling, and safety | Drivability problems under some conditions and contribution of design changes | New model optimisation with quantitative testing to assess comfort, handling and energy consumption |

| Baronio, G.; Bodini, I.; Motyl, B.; Uberti, S. 2017 (Italy) [11] | Gölem project: Concept and design of a trekking/hiking wheelchair (Article) | Design and test an improved model of a hiking wheelchair | Mixed | Experimental tests on performance, such as stability, material strength, and handling | Improvement over commercially available aids in comfortand functionality | Improving handling in extreme terrain, and customization for users with different needs |

| Benjamin, S., Bottone, E., & Lee, M. 2020 (USA) [31] | Beyond accessibility: exploring the representation of people with disabilities in tourism promotional materials (Article) | How are represented PWDs in promotional materials, particularly in brochures tourism | Qualitative | Content analysis of 211 tourism brochures, from nine southeastern U.S. states | Images and text referring to PwDs rarely appear in promotional materials | Broaden the context of analysis and directly involve tourism stakeholders |

| Bianchi, P.; Cappelletti, G.M.; Mafrolla, E.; Sica, E.; Sisto, R. 2020 (Italy) [14] | Accessible Tourism in Natural Park Areas: A Social Network Analysis to Discard Barriers and Provide Information for People with Disabilities (Article) | How accessibility information is shared among stakeholders in the Gargano Park (southern Italy) and how it can be improved to foster inclusive tourism | Quantitative | Social Network Analysis (SNA), focuses on relationships and information flows among stakeholders using mathematical and statistical tools | The information flow is dominated by a single government administration, while some nodes remain passive | Involve users in decisions and foster more effective exchange of information among stakeholders |

| Blaszczyk M.; Suchocka M.; Wojnowska-Heciak M.; Muszynska M. 2020 (Poland) [5] | Quality of urban parks in the perception of city residents with mobility difficulties (Article) | Availability and accessibility of parks | Qualitative | Questionnaire, survey | Typical activities of people with limited mobility and most dominant barriers | Recommendations and guidelines for accessibility of disabled people in parks |

| Chikuta, O.; du Plessis, E.; & Saayman, M. 2018 (South Africa) [32] | Accessibility Expectations of Tourists with Disabilities in National Parks (Article) | Expectations and needs of PwDs regarding accessibility of national parks | Mixed | Online questionnaire with demographic and accessibility expectations data | Strong desire for autonomy of PwDs. Universal design of natural spaces | Representativeness of the sample |

| Cloquet, I.; Palomino, M.; Shaw, G.; Stephen, G.: & Taylor, T. 2017 (UK) [33] | Disability, social inclusion and the marketing of tourist attractions (Article) | How tourist attractions in Cornwall (England) address the inclusion of PwDs through marketing and communication strategies | Mixed | Analysis of brochures and websites | Poorly considered accessibility information in both text and images | Does not integrate PwDs’ views and does not propose concrete operational solutions |

| Club Alpino Italiano 2021 (Italy) [34] | Classificazione dei percorsi montani accessibili con ausili (Manual) | Classification of difficulty of accessible routes with aids for people with motor disabilities | - | It is not a scientific study. It is based on criteria developed by the Italian Alpine Club in collaboration with other bodies | Three route classes with specific technical require-ments | Not all possible aids for people with motor disabilities are considered |

| Corazon, S. S.; Gramkov, M. C.; Poulsen, D. V.; Lygum, V. L.; Zhang, G.; & Stigsdotter, U. K. 2019 (Denmark) [15] | I Would Really like to Visit the Forest, but it is Just Too Difficult: A Qualitative Study on Mobility Disability and Green Spaces (Article) | Experiences and related constraints of individuals with mobility disabilities visiting green space | Qualitative | Group and individual interviews | Structural problems of trails and lack of accessibility information on websites | Practical solutions that could facilitate access to trails |

| Darcy, S.; Cameron, B.; & Pegg, S. 2010 (Australia) [35] | Accessible tourism and sustainability: a discussion and case study (Article) | Exploring the interrelationship between accessible tourism and sustainability | Qualitative | Analysis of secondary sources, such as planning documents, guidelines, institutional reports, and technical publications | Accessibility is fully compatible with the three pillars of sustainability: environmental, social, economic | Limitations related to absence of empirical data, lack of generalizability of the case, and lack of evaluative tools |

| Eusébio, C., Alves, J. P., Carneiro, M. J., & Teixeira, L. 2024 (Portugal) [4] | Needs, motivations, constraints and benefits of people with disabilities participating in tourism activities: the view of formal caregivers (Article) | Exploring formal caregivers’ perceptions of the needs, motivations, constraints, and benefits of tourism for PwDS | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews with formal caregivers | Several strategic recommendations: improve accessibility, train staff, and provide clear information | Operational indications not translated concretely into effective and sustainable policies or projects over time |

| Fialová J.; Kotásková P.; Schneider J.; Žmolíková N.; Procházková P. 2018 (Czech Republic) [19] | Geo-caching for wheelchair users: a pilot study in luhacovské zálesí (czech republic) (Article) | Evaluate the accessibility of geocaching activities for wheelchair users | Mixed | Numerical data regarding the physical characteristics of the trails. User feedback | Rules for establishing caches suitable for wheelchair users | Rules accepted by at least some of the gaming community |

| Fieldfare Trust Ltd. 2005 (UK) [26] | Countryside for All. Good Practice Guide: A Guide to Disabled People’s Access in the Countryside (Technical Manual) | Practical guidelines for improving the accessibility of natural environments to PwDs by promoting an inclusive approach in design | - | It is not a scientific study, but an operational guide. It is based on field experiences, best practices and current regulations | Disseminate inclusive standards for accessibility in rural settings, influencing public agencies and trail managers | It does not solve the difficulties of application in complex natural settings. The absence of updates for years has made some directions outdated |

| Garrod, B.; & Fennell, D. A. 2021 (UK) [36] | Strategic approaches to accessible ecotourism: small steps, the domino effect and not paving paradise (Article) | Exploring strategic approaches to make hiking accessible to PwDs, without compromising the environmental integrity of natural places | Qualitative | Interviews with accessible ecotourism providers and consultants from different countries | Three strategies: small steps incremental, the domino effect of barriers, and an approach for environmental conservation | Conflict between goals of accessibility and preservation |

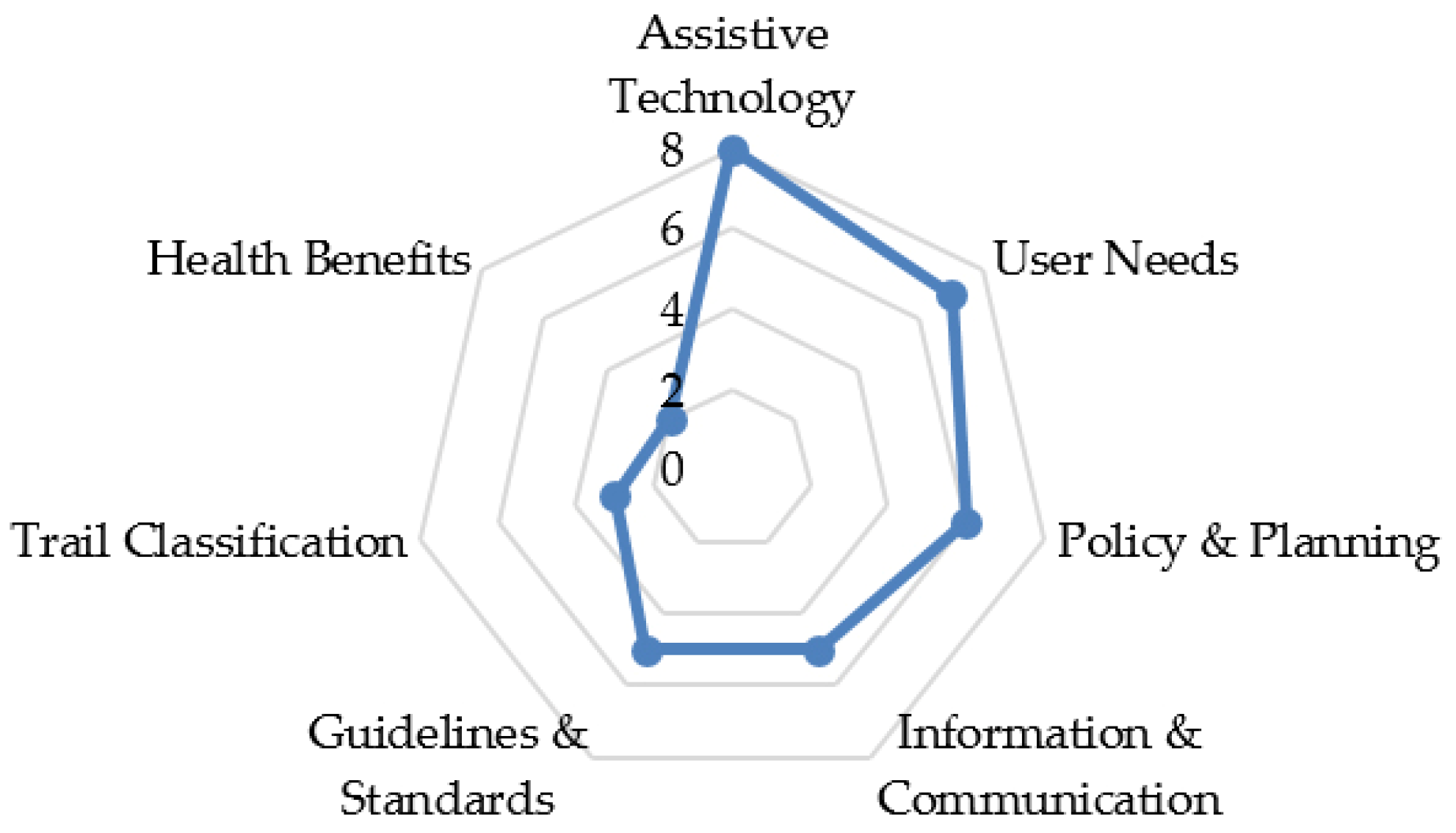

| Godtman Kling, K. & Ioannides, D. 2022 (Sweden) [16] | Enhancing Accessibility in Tourism and Outdoor Recreation: A Review of Major Research Themes and a Glance at Best Practice (Technical Report) | Analyse major research topics on accessibility in tourism and outdoor recreation, highlighting existing good practices | Qualitative | Narrative literature review, collection and qualitative analysis of case studies and best practices | Identifies five macro-themes and reports good practices based on inclusive design and participation | Fragmentary studies and lack of internationally comparable data |

| Groulx, M., Lemieux, C., Freeman, S., Cameron, J., Wright, P. A., & Healy, T. 2021 (Canada) [25] | Participatory planning for the future of accessible nature (Article) | How participatory processes can improve the design of accessible natural spaces by involving PwDs and other stakeholders | Qualitative | Workshops, interviews and moments of collective discussion | Best practices for inclusive design and development of practical guidelines for actively engaging PwDs | Lack of resources to implement solutions, difficulty in involving all stakeholder groups, bureaucratic barriers |

| Irish Wheelchair Association; Sport Ireland 2018 (Ireland) [28] | Great Outdoors—A guide for accessibility (Technical Manual) | Making natural spaces in Ireland accessible to all, including PwDs | - | Participatory methodology, involving PwDs and stakeholders through consultations and self-assessments | Inclusive design of trails and parks according to Universal Design | Difficulties in rugged natural terrain and the need for more training among operators |

| Leaman, J.; La, H.M. 2017 (USA) [37] | A Comprehensive Review of Smart Wheelchairs: Past, Present, and Future (Review) | Aims to provide a systematic review of Smart Wheelchair | Mixed | Systematic literature review | Main research trends, such as autonomy, intelligent navigation, and human–machine interaction | Limited autonomous navigation, unintuitive user interfaces, sensor reliability, high cost. |

| Lepoglavec K.; Papeš O.; Lovrić V.; Raspudić A.; Nevečerel H. 2023 (Croatia) [22] | Accessibility of urban forests and parks for people with disabilities in wheelchairs, considering the surface and longitudinal slope of the trails (Article) | Accessibility of urban forests and parks for people with disabilities in wheelchairs | Quantitative | Test of measurement of the mobility of people in wheelchairs | Classification of paths based on slope | Consider different surfaces for slope categorization and park management guidelines |

| Janeczko, E.; Jakubisová, M.; Woźnicka, M.; Fialova, J. & Kotásková, P. 2016 (Poland; Slovak Republic; Czech Republic) [9] | Preferences of people with disabilities on wheelchairs in relation to forest trails for recreational in selected European countries (Article) | Analyse the preferences of wheelchair users regarding recreational forest trails in some European countries | Quantitative | Collection and analysis of data through questionnaires to people with mobility disabilities who use wheelchairs | Surface and slope of trails, along with the presence of accessible facilities, are crucial elements | Does not conduct a direct survey of pathways with PwDs |

| Lundell, Y. 2005 (Sweden) [20] | Access to the Forests for Disabled People (Technical Manual) | Guidelines on accessibility of forest areas for PwDs, focusing mainly on those with mobility or visual impairments | - | It is not a scientific study, but an operational guide. It is based on field experiences and best practices | Improving the accessibility of Sweden’s forests by providing guidelines and raising awareness among forest managers | Structural, economic, and cultural constraints to a full accessibility of forests |

| McCabe, S., & Diekmann, A. 2015 (UK; Belgium) [2] | The rights to tourism: reflections on social tourism and human rights (Article) | Analyse whether tourism can be recognised as a social right and reflect on its role in inclusion through social tourism | - | Conceptual and argumentative approach | Reconsidering tourism as a social right, recognising its potential to promote justice and inclusion | Operational, legal and empirical issues concerning the effective implementation of the ‘right to tourism’ |

| Moura, A. F. A., Kastenholz, E., & Pereira, A. M. S. 2017 (Portugal) [3] | Accessible tourism and its benefits for coping with stress | Exploring whether and how accessible tourism can contribute to stress management in PwDs | Quantitative | Leisure Coping Scale, specifically adapted to the context of accessible tourism. Sample of 306 PwDs | The value of tourism as a coping resource and suggest its integration into policies and therapeutic practices | Limitations in the generalizability of the results. It does not explore structural barriers to access and lacks a comparison with people without disabilities. |

| National Confederation of Disabled People of Greece 2019 (Greece) [27] | Guidebook for Accessible Nature Trails: Design Guidelines and Evaluation System | Guidelines and an evaluation system for designing accessible nature trails, especially for people with mobility disabilities | - | Literature review, participatory design approach and practical field observations | Practical guidelines for accessible trail design and evaluation system for accessibility of existing trails | Lack of uniformity due to the variability of nature trails, and the difficulty of maintaining accessible trails over time |

| Poldma T.; Carbonneau H.; Miaux S.; Mazer B.; Le Dorze G.; Gilbert A.; Hammouni Z.; El-Khatib A. 2017 (Canada) [17] | Lived experiences and technology in the design of urban nature parks for accessibility (Conference paper) | Mobility challenges in urban parks for people with wheelchair disabilities | Qualitative | User conversations and observations in real time | Navigation technologies such as mobility apps improve access to parks | Physical barriers and poor information and way-finding |

| Rowiński, R.; Morgulec-Adamowicz, N.; Ogonowska-Slodownik, A.; Dąbrowski, A.; Geigle, PR. 2017 (Poland; USA) [8] | Participation in leisure activities and tourism among older people with and without disabilities in Poland (Article) | To compare physical activity and participation in recreational and tourist activities among older people with and without disabilities in Poland | Quantitative | Analysis of data from a large-scale survey targeting 3743 elderly people in Poland | PwDs are less active in tourism and physical activities | The needs of PwDs in relation to recreation and tourism activities are not addressed |

| Shen, Xj.; Huang, Rh. & Zhang, Js. 2019 (China; Usa) [7] | U.S. national parks accessibility and visitation (Article) | Analyses the accessibility of U.S. parks, examining physical barriers and proposing solutions for PwDs | Quantitative | Analysis of the correlation between visitation and accessibility, according to park types | Accessibility for PwDs influences the number of visits to national parks variably | Causes of correlations between accessibility and attendance are not explored in depth |

| Singh, R., Sibi, P. S., Yost, E., & Mann, D. S. 2021 (India; USA) [1] | Tourism and disability: a bibliometric review (Review) | Analyse research on tourism and disability, mapping trends, relationships, and emerging themes in the field | Quantitative | Bibliometric analysis | Growth in research on tourism and disability. Key topics: assistive technology, sustainable tourism and dedicated marketing | Limited geographical coverage. Little integration between theoretical and practical approaches. |

| Sreevatsav, S.; Sheth, S.; Kumar, A.; Dwivedy, B. 2023 (India) [13] | An iot enabled smart wheelchair solution for physically challenged people (Conference paper) | IoT smart wheelchair enhances mobility, autonomy, and safety | Quantitative | Design and development of the prototype | Enhancement of a traditional wheelchair’s functionalities. | Reliability in real-world conditions. Cost |

| Sukerkar, K.; Suratwala, D.; Saravade, A.; Patil, J.; D’britto, R. 2018 (India) [38] | Smart Wheelchair: A Literature Review (Review) | Aims to analyse the current state of smart wheelchair technology | Qualitative | Literature review | Technological advances in smart wheelchairs, integrating AI, robotics and sensors | Challenges such as high cost, accessibility and reliability |

| Svizzera Mobile (Switzerland) [39] | Obstacle-Free Routes, Grade of Difficulty (Manual) | Provide difficulty levels for trails for PwDs | - | It is not a scientific study, but an operational guide. It is based on criteria developed by various organisations and PwDs | Three route classes with specific technical requirements | Not all possible aids for people with motor disabilities are considered |

| Wall-Reinius, S.; Kling, K. G.; & Ioannides, D. 2022 (Sweden) [24] | Access to Nature for Persons with Disabilities: Perspectives and Practices of Swedish Tourism Providers (Article) | Challenges and opportunities of tourism service providers in Sweden in providing access to nature for PwDs | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews conducted with tourism service providers | Positive examples of inclusive practices and readiness for change emerge, if supported by appropriate training and policies | Accessibility to nature for PwDs is still not a priority for many tour operators, due to cultural, economic and regulatory barriers |

| Zeller, J.; Doyle, R.; Snodgrass, K. 2012 (USA) [21] | Accessibility Guidebook for Outdoor Recreation and Trails (Technical manual) | Provide technical and operational guidelines for making outdoor recreation and trails accessible to PwDs | - | Analysis of existing standards, experiences practices, and accessibility guidelines | Technical reference tool and regulatory tool to ensure equal access to nature | Adaptability to specific contexts, cost of implementation, long-term maintenance. Does not include different disabilities |

| Zhang, G.; Poulsen, D.V.; Lygum, V.L.; Corazon, S.S.; Gramkow, M.C.; Stigsdotter, U.K. 2017 (Denmark) [6] | Health-Promoting Nature Access for People with Mobility Impairments: A Systematic Review (Review) | Systematically evaluate scientific evidence for health benefits of natural environments for people with mobility impairments | Mixed | Systematic literature review | Access to nature brings physical, mental and social benefits to people with developmental disabilities | Persistence of numerous environmental and social barriers |

| Model | Voltage Battery | Power Motor | Diam./Width Tyre | Weight 1 | Range 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRIRIDE [44] | |||||

| Kids | 36 V | 540 W | 12″ | 7.5 kg | 35 km |

| Folding | 36 V | 670 W | 12″ | 8.2 kg | 35 km |

| Light | 36 V/48 V | 670 W/890 W | 12″/14″ | 8.5 kg | 50 km |

| Light 10″ | 36 V/48 V | 670 W/890 W | 10″ | 7.8 kg | 50 km |

| Special Light | 36 V/48 V | 900 W/1200 W | 12″/14″ | 8.5 kg | 50 km |

| Special Compact HT | 36 V/48 V | 1000 W/1400 W | 12″ | 11 kg | 50 km |

| Special L14 | 48 V | 1500 W | 14″ | 11.9 kg | 50 km |

| Special HP16 | 48 V | 1500 W | 16″ | 12.8 kg | 50 km |

| Mad Max | 48 V | 1500 W | 16″ | 12.8 kg | 50 km |

| T-Rocks | 48 V | 1500 W | 16 × 4 | 12.8 kg | 50 km |

| KLAXON MOBILITY [43] | |||||

| Klick Power | 48 V | 750 W | 14″ | 8.5 kg | 50 km |

| Klick Race | 48 V | 1500 W | 14″ | 11.4 kg | 50 km |

| Klick Monster | 48 V | 1500 W | 20″ | 15 kg | 50 km |

| BATEC MOBILITY [42] | |||||

| Batec Mini 2 | 36 V | 350 W | 12 × 2.40 | 12.9 kg | 52 km |

| Batec Electric 2 | 36 V | 900 W | 18 × 2.40 | 15.9 kg | 35 km |

| Batec Rapid 2 | 36 V/48 V | 1440 W | 18 × 2.40 | 15.9 kg | 50 km |

| Batec Scrambler 2 | 36 V/48 V | 1440 W | 19 × 2.75 | 16.7 kg | 50 km |

| Lundell, Y. (2005) [20] | Zeller, J. (2012) [21] | Lepoglavec, K. (2023) [22] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Category | Assistance Required | Slope | Max. Length of Segment | Slope | Max. Length of Segment | Slope | Max. Length of Segment |

| easy | Little or no assistance required | ≤5% | - | ≤5% | - | ≤5.5% | - |

| moderate | May require assistance | >5% | 5 m | 5–8.33% | 61 m | 5.51–9.01% | - |

| difficult | Assistance required | - | - | 8.33–10% | 9 m | - | - |

| most difficult | Assistance sorely required | ≥5% | - | 10–12% | 3.05 m | >9.01% | - |

| Difficulty Levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessible to Tourists | Accessible to Hikers | Accessible to Expert Hikers | ||

| Characteristics of the trails | Slope | <8% | <16% | >16% |

| Width | >1.5 m | 1.0–1.5 m | <1 m | |

| Diff. in altitude | <150 m | 150–300 m | >300 m | |

| Length | <3 km | 3–6 km | >6 km | |

| Surface | Firm and stable | Irregular | Bumpy | |

| Tread Obstacles | No obstacles | Few natural or artificial steps | Natural or artificial steps > 10 cm; Significant obstacles | |

| Access requirements | Slope < 4 ÷ 5% with a self-propelled wheelchair. Slope > 5% with a single-wheel all-terrain chair, and the help of at least two assistants. | Single-wheel all-terrain chair, with the help of at least two assistants. Evaluation of the hiking time in relation to critical issues | Single-wheel all-terrain chair: requires skills, techniques, experience and an adequately sized crew | |

| Difficulty Levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Medium | Difficult | ||

| Characteristics of the trails | Average slope | no significant ascents | <6% | <12% |

| Max. slope | 8% | 12% | 20% | |

| Transverse slope | ≤4% | ≤6% | ≤10% | |

| Path width | ≥1.80 m, narrow spots ≥ 0.80 m | ≥1.20 m, narrow spots ≥ 0.80 m | ≥1.00 m, narrow spots ≥ 0.80 m | |

| Nature of the terrain | - Asphalt and concrete surfaces. - Paving slabs and stones with max. 10 mm wide open joints (also applies to planking). - Water-bound natural surfaces (e.g., marl surfaces). Single steps up to 30 mm in height. | - Asphalt and concrete surfaces. - Paving slabs and stones with max. 10 mm wide open joints (also applies to planking). - Water-bound natural surfaces (e.g., marl surfaces). Single steps up to 50 mm in height. | - Asphalt and concrete surfaces. - Paving slabs and stones with max 10 mm wide open joints in the longitudinal direction and max 30 mm wide in a lateral direction. - Water-bound natural surfaces (e.g., marl surfaces). Single steps up to 50 mm in height. | |

| Conditions | Easy | Medium | Difficult | |

| Length | up to 4 km | up to 8 km | over 8 km | |

| Altitude difference | up to 50 metres | up to 100 metres | over 100 metres | |

| Time required | up to 1.5 h | up to 3.5 h | over 3.5 h | |

| Nature of the terrain | 80% of the route is paved | 50% of the route is paved | less than 50% of the route is paved | |

| Access requirements | Suitable for self-propelled wheelchairs | Suitable for self-propelled wheelchairs, for disabled people with a sporting aptitude or accompanied; or for motorised wheelchairs or scooters | Suitable for wheelchair auxiliary drives, such as attachable motors | |

| Characteristics of the Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Criteria | Document Type | Running Tests | Aids | Parameters | Path Category |

| Lundell, Y. (2005) [20] | Manual | no | - Wheelchair | - Slope - Max. length of segment | - Easy - Moderate - Most difficult |

| Zeller, J. (2012) [21] | Manual | no | - Wheelchair | - Slope - Max. length of segment | - Easy - Moderate - Difficult - Most difficult |

| Lepoglavec, K. (2023) [22] | Article | yes | - Wheelchair | - Slope - Macadam surface | - Easy - Moderate - Most difficult |

| Club Alpino Italiano (2021) [34] | Classification Document | no | - Wheelchair - Joëlette | - Slope - Path width - Difference in altitude - Length - Surface - Tread obstacles | - Accessible to tourists - Accessible to hikers - Accessible to expert hikers |

| Svizzera Mobile [39] | Manual | no | - Wheelchair - Power Device | - Average slope - Max slope - Transverse slope - Path width - Difference in altitude - Length - Surface | - Easy - Medium - Difficult |

| Aids | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty Level | Characteristics of the Trails | Wheelchair | Wheelchair Assistant | Power Device | Joëlette |

| I | average slope < 5% maximum slope 5% surface: firm and stable | • | • | • | • |

| II | average slope < 5% maximum slope 9% surface: firm and stable | • * | • | • | • |

| III | average slope < 6% maximum slope 12% surface: firm and stable | • | • | • | |

| IV | average slope < 10% maximum slope 16% surface: irregular | • | • | ||

| V | average slope < 12% maximum slope 20% surface: irregular | • | • ** | ||

| VI | average slope ≥ 12% maximum slope ≥ 20% surface: bumpy | • *** | • ** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mantuano, A.; Bruno, F. Classification of Hiking Difficulty Levels of Accessible Natural Trails. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135699

Mantuano A, Bruno F. Classification of Hiking Difficulty Levels of Accessible Natural Trails. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135699

Chicago/Turabian StyleMantuano, Alessandro, and Fabio Bruno. 2025. "Classification of Hiking Difficulty Levels of Accessible Natural Trails" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135699

APA StyleMantuano, A., & Bruno, F. (2025). Classification of Hiking Difficulty Levels of Accessible Natural Trails. Sustainability, 17(13), 5699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135699