Sustainable Concentration in the Polish Food Industry in the Context of the EU-MERCOSUR Trade Agreement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concentration Versus Economic Efficiency of Food Industry

2.2. Economies of Scale

- Improving the bargaining position vis-à-vis domestic and foreign counterparties;

- Better access to operational funding (e.g., loans, subsidies);

- Increase the possibility of investment and implementation of modern production technologies;

- Implementing specialist management techniques;

- Economic cooperation and co-operation with other companies on the basis of the creation of oligopolistic structures that create high barriers to entry for competitors;

- Intensive product promotion;

2.3. Concentration in the View of Sustainable Development of Enterprises and UE-MERCOSUR Agreement

3. Materials and Methods

- Small: with up to 49 employees;

- Medium: with 50–249 employees;

- Large: employing 250 or more employees.

4. Research Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The food industry in Poland is an important sector of the economy, which reflects strong demand for domestic and imported agricultural raw materials, a significant share in the value of production and employment in the entire industry sector, and a large positive balance of foreign trade. Enterprises have undergone a process of profound ownership, structural and modernisation changes in order to adapt to the changing environment: liberalisation of foreign trade under GATT/WTO, accession to the EU and reforms of the CAP, as well as growing production and trade risks, which have been generated by global economic crises, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and progressive climate change. In the coming years, a major challenge for the food industry will be the liberalisation of foreign trade under bilateral agreements (e.g., with MERCOSUR countries). As a consequence, major changes in the competitive conditions on the international market are expected so that only economically strong and efficient companies will be able to retain their competitive position, which would require significant investments.

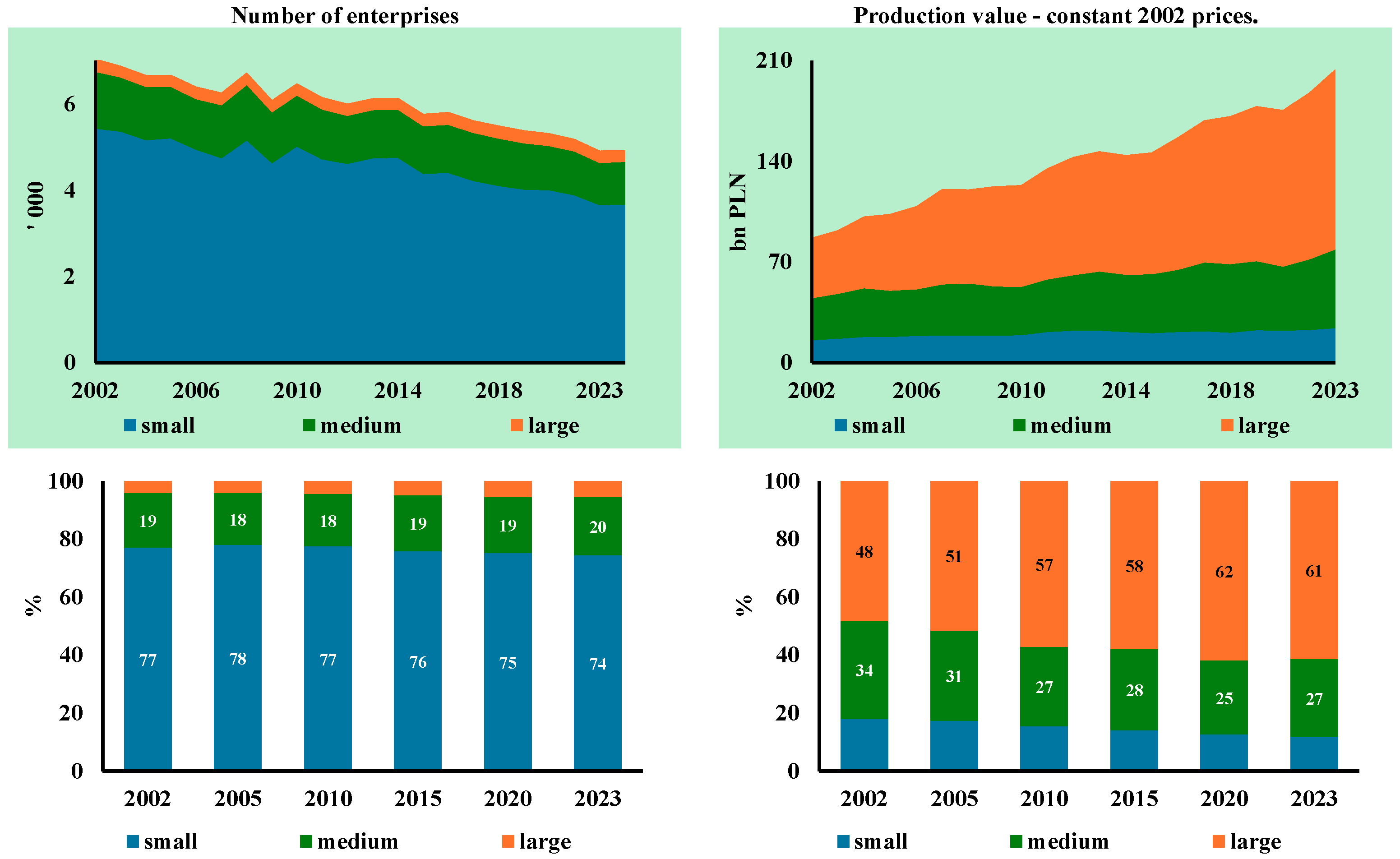

- The research results showed a growing concentration of the Polish food industry. The changes in its structure have been undergoing with an evolutionary pattern, which is confirmed by a still high degree of fragmentation within the branch. Large enterprises effectively take advantage of economies of scale, which is mirrored in their high level of efficiency.

- Over the period of 2002–2023, the Polish food industry continued the processes of structural transformation. This was confirmed by a decrease in the number of enterprises and a significant share of large companies in the production structure. Small and medium-sized enterprises decreased their share in production, but the structure of the sector is still characterised by high fragmentation. The research showed that the average value of output per enterprise more than tripled in real terms. The decrease in the number of enterprises was accompanied by a reduction in employment, with the average employment per company increasing by 36.4%. The results of the research undoubtfully confirmed the continuation of concentration processes in large enterprises, with their increased economic power resulting in a strengthened bargaining position versus both domestic and foreign competitors, which confirms the stated research hypothesis. Small enterprises, which produce for local markets within short supply chains, are an important element of regional development; however, they do not affect the international competitiveness of the Polish food industry. The market position of small enterprises will be eroded due to high entry barriers. Nevertheless, small companies would still remain in the structure of the food industry due to strong linkages with agriculture and diversification of activities in line with modern food trends. Consequently, the structure of the food industry assures the achievement of sustainable development objectives under conditions of foreign trade liberalisation.

- The concentration of the food industry structure was accompanied by large investments, with the total value reaching PLN 132.5 billion in real terms. At the same time, the value of total capital and labour increased in real terms by 83.0% and 68.2%, respectively. Reflecting that, technical utilisation of labour increased, and the production of the food industry became more capital-intensive than labour-intensive. Estimation of the Cobb–Douglas production function showed that its elasticity with respect to capital was many times higher than its elasticity with respect to labour. As a result, there was a substitution of labour by capital. The research showed that food industry enterprises operate on fixed economies of scale, as the sum of the elasticity coefficients of labour and capital is close to 1. The economies of scale indicate that the structural transformation and modernisation of enterprises were highly successful, and this was confirmed by increasing profits and competitiveness in the international market, indicating that enterprises are well prepared for the implementation of the trade agreement with MERCOSUR countries.

- Due to the economic transformation in the EU, the food industry has been implementing the innovative solutions of Industry 4.0, a sustainable resource management in a closed model. The aim of these changes is to improve economic efficiency (e.g., cost reduction) and maintain competitiveness. Structural change and modernisation in the food industry are not yet complete and will continue in the future, and will be determined by EU climate policy and the liberalisation of foreign trade with MERCOSUR countries. Preferential import quotas will result in increased competition, as the production of agricultural raw materials in MERCOSUR countries takes place under favourable climatic conditions, liberal regulations on GMOs and pesticides, and in very large farms and industries that benefit from economies of scale and have a strong bargaining position versus contractors. This situation may mean that the benefits of this liberalisation will accrue primarily in the large food corporations, while smaller-scale enterprises will be confronted with new competitive conditions.

- The results of the research contribute to a more comprehensive approach to the problem of concentration impact on the factor efficiency of food industry enterprises, as well as on the possibilities of sustainable development of the food industry. So far, studies of structural, ownership and modernisation changes, as well as those focused on financial performance, have shown great variation across food industries. Therefore, further research on concentration and economies of scale, including the use of production functions, should be continued in a broader and conducted for particular branches of the food industry. The results of these studies will make it possible to assess factor inputs and their marginal productivity, elasticity, substitution and technical armament of labour. On such a basis, it will be possible to assess economies of scale in particular industries and to identify further directions for investment in order to improve the structure, modernisation level and sustainability. The development of the research should also include the identification of possible sources and areas of concentration inefficiencies. The cognitive and application value of this research can be a complementary element of economic analyses of concentration processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szczepaniak, I.; Ambroziak, Ł.; Bułkowska, M.; Drożdż, J. Importance of the food industry in the economy of Poland and the European Union. Food Ind. 2022, 76, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Office. Statistical Yearbook of Industry 2024. 28 February 2025. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-statystyczny-przemyslu-2024,5,18.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Bulkowska, M. Rozwój Polskiego Eksportu Rolno-Spożywczego w Świetle Modelu Grawitacji; Studia i Monografie No. 197; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, P. Consolidation of the Polish Food Industry Against the Background of the EU. Will the Difficult Economic Envi-ronment Accelerate the Growth of Sector Concentration? Report by Bank Pekao, Macroeconomic Analysis Department. June 2022. Available online: https://www.pekao.com.pl/dam/jcr:2c6718c9-4c68-4d09-bfaf-97d04c8ad2aa/Konsolidacja%20polskiej%20bran%C5%BCy%20spo%C5%BCywczej_czerwiec%202022.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Szczepaniak, I. Transformation of the Subjective Structure of the Polish Food Industry in 2004–2016. In Proceedings of the Conference Hradec Economic Days, University of Hradec Králové, Faculty of Informatics and Management, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 5–6 February 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraciuk, J. Concentration of production in the Polish food industry. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Probl. World Agric. 2008, 5, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczyk, Z. Objectives of antitrust policy in theory and practice. In Konkurencja w Gospodarce Współczesnej; Banasiński, C., Stawicki, E., Eds.; UOKiK: Warsaw, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Methods of Sector and Competitor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the Implementation of the Rules on Competition Laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty, OJL 1/1, 04.01.2003. 2003. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2003/1/oj/eng (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the Control of Concentrations Between Undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation), OJL 24, 29.01.2004. 2004. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2004/139/oj/eng (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Act of 24 February 1990 on Antitrust. J. Laws 1990, 14, 88. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19900140088 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Kuna-Marszałek, A. Liberalization of International Trade and the Natural Environment: The Example of the European Union; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski, K.; Rokita, J. Risk associated with international trade and methods of its reduction. Ed. Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Górnośląskiej 2023, 257–268. Available online: https://www.gwsh.pl/content/biblioteka/org/zeszyty/ag/zn12/ZN12AG_24Szaflarski.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, I. Entity structure of the food industry. In Processes of Adjustment of the Polish Food Industry to the Changing Market Environment (2); Mroczek, R., Ed.; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heimstra, S.J. Concentration and Competition in the Food Industries. J. Farm Econ. 1966, 48, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, J.-P.; Bonroy, O.; Couture, S. Economies of Scale in the Canadian Food Processing Industry. MPRA Paper 2006, No. 64. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/64/1/MPRA_paper_64.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Collins, N.R.; Preston, L.P. Concentration and Price-Cost Margins in Food Manufacturing Industries. J. Ind. Econ. 1966, 14, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.H. Concentration and Power in the Food System: Who Controls What We Eat? Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kufel, J.; Hamulczuk, M. Concentration and the exertion of market power in the Polish food industry. Rocz. Nauk. Ser. 2015, 17, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek, R.; Drożdż, J.; Tereszczuk, M.; Urban, R. No. 117.1—Polish food industry 2008–2013. In Multiannual Program Reports 206063; Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics—National Research Institute (IAFE-NRI): Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E. Efektywność przedsiębiorstw—Definiowanie i pomiar. Rocz. Nauk. Ekon. Rol. I Rozw. Obsz. Wiej. 2010, 97, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwonka, L.; Pankau, E. Application of market concentration indices to assess capital concentration in the world economy. In Functioning of the Polish Economy Under Conditions of Integration and Globalization; Kopycińska, D., Ed.; Katedra Mikroekonomii Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego: Szczecin, Poland, 2005; pp. 291–297. ISBN 83-917487-6-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, J. Relation of profit rate to industry concentration: American Manufacturing 1936–1940. Q. J. Econ. 1951, 65, 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsetz, H. Industry structure, market rivalry, and public policy. J. Law Econ. 1973, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G.J. The Organization of Industry; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, J. Barriers to New Competition: Their Character and Consequences in Manufacturing Industries; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, R.R. Competitive Strategy—Relevance in Food Processing Industry. Manag. Res. 2022, 28, 1–10. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4122935 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Brozen, Y. Concentration and structural and market disequilibria. Antitrust Bull. 1971, 16, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, R. Przemiany Przemysłu Spożywczego w Latach 1988–2003; Studia i Monografie No. 121; IERiGŻ: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rondinelli, D.A.; Yurkiewicz, Y. Privatization and Economic Restructuring in Poland: An Assessment of Transition Policies. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2006, 55, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chechelski, P.; Kwasek, M.; Mroczek, R. Changes in the Food Industry Environment Under the Influence of Globalization: Selected Problems; Studies and Monographs No. 164; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hanus, G. The Phenomena of Globalisation in Polish Consumers’ Food Choices. Optimum. Econ. Stud. 2021, 104, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnicka, E. Foreign Direct Investment in the Privatisation of the Polish Economy. Intereconomics 2001, 36, 6. Available online: https://www.intereconomics.eu/pdf-download/year/2001/number/6/article/foreign-direct-investment-in-the-privatisation-of-the-polish-economy.html (accessed on 10 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chechelski, P. Wpływ Procesów Globalizacji na Polski Przemysł Spożywczy; Studia i Monografie No. 145; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chechelski, P. State Policy Towards Food Industry in Time of Integration and Globalization. Equilibrium Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2010, 4, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, I.; Szajner, P. The Evolution of the Agri-Food Sector in Terms of Economic Transformation, Membership in the EU and Globalization of the World Economy. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2020, 365, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. Schedule LXV—Poland, Part IV—Agricultural Products—Commitments Limiting Subsidization; Article 3 of the Agreement on Agriculture, Section I—Domestic Support: Total AMS Commitments 1994. Available online: https://www.wto.org (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Zielińska-Głębocka, A. The European Union. Poland’s Preparation for Membership; Kawecka-Wyrzykowska, E., Synowiec, E., Eds.; Instytut Koniunktur i Cen Handlu Zagranicznego: Warsaw, Poland, 2001; pp. 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Seremak-Bulge, J. (Ed.) Foreign Trade in Agri-Food Products 1995–2009; Studies and Monographs No. 152; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morkis, G. (Ed.) No. 42—Status of Implementation of Quality Management Systems in Food Industry Enterprises; Publications of the Multi-Annual Programme 2005–2009; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2006; Available online: http://www.ierigz.waw.pl/publikacje/raporty-programu-wieloletniego-2005-2009/1314196064 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Cieślewicz, W. Financial support of investments in the Polish agri-food industry. Probl. World Agric. Sci. J. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. 2011, 11, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bułkowska, M.; Chmurzyńska, K. No. 65—Results of Implementation of RDP and SOP “Agriculture” in 2004–2006; Publications of the Multi-Annual Programme 2005–2009; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2007; Available online: http://ierigz.waw.pl/publikacje/raporty-programu-wieloletniego-2005-2009/1314191097 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Giuliani, A.; Baron, H. The CAP (Common Agricultural Policy): A Short History of Crises and Major Transformations of European Agriculture. Forum Soc. Econ. 2023, 54, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Group. Indicators. Economy & Growth. GDP per Capita, PPP (Current International $). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?view=chart (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Mroczek, R. (Ed.) No. 12—Structural Changes of the Food Industry in Poland and the EU Against the Background of Selected Elements of the External Environment; Publications of the Multiannual Programme 2015–2019; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Firlej, K.; Kowalska, A.; Piwowar, A. Competitiveness and innovation of the Polish food industry. Agric. Econ. 2017, 63, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, I. Pozycja Konkurencyjna Polski w Handlu Zagranicznym Produktami Rolno-Spożywczymi na Wybranych Rynkach in Szczepaniak I. Competitiveness of Polish Food Producers and Its Determinants (4); Publications of the Multiannual Programme 2015–2019; No. 86; Instytut Ekonomiki Rolnictwa i Gospodarki Żywnościowej—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 9–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdż, J. Analiza Ekonomiczno-Finansowa Wybranych Branż Przemysłu Spożywczego w Latach 2003–2009; Studia i Monografie No. 151; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, A.; Wigier, M. No. 147.1—Competitiveness of the Polish Food Economy in the Conditions of Globalization and European Integration; Multiannual Program Reports 2011–2014; IERiGŻ-PIB: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; Available online: https://open.icm.edu.pl/handle/123456789/7987 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Szymczyk, K. International Market Expansion by the Polish Food Industry: Reasons, Strategic Goals and Methods. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G.J. The Economies of Scale. J. Law Econ. 1958, 1, 54–71. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/724882 (accessed on 15 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Varian, H.R. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach, Eighth Edition; W. W. Norton & Company Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Łyszkiewicz, W. Industrial Organization. Organizacja Rynku i Konkurencji; Wyższa Szkoła Handlu i Finansów Międzynarodowych; Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa: Warsaw, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, D.K.; Kehoe, P.J.; Kehoe, T.J. In search of scale effects in trade and growth. J. Econ. Theory 1992, 58, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresch, A.; Collatto, D.C.; Lacerda, D.P. Theoretical understanding between competitiveness and productivity: Firm level. Ing. Y Compet. 2018, 20, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.A.; Azzam, A.M.; Liron-Espana, C. Market Power and/or Efficiency: A Structural Approach. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2002, 20, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, E.H. The Role of Economic Efficiency and Business Strategy to Achieve Competitive Advantage. PEOPLE Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, I.; Satiawan, D. Business Strategies and Competitive Advantage: The Role of Performance and Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, M. Market competition, efficiency and economic liberty. Int. Rev. Econ. 2023, 70, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J. The problem with growing corporate concentration and power in the global food system. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Economies of scale and international business cycles. J. Int. Econ. 2021, 131, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J. The Agri-Food System in Question; Innovations, Contestations, and New Global Players; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.; Gerts, A. The Global Economic Crisis of 2008–2009: Sources and Causes. Probl. Econ. Transit. 2010, 53, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, I. The Global Economic Crisis and the Competiveness of Polish Food Procuders. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2012, 7, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakat, Z.; Bou-Mitri, C. COVID-19 and the food industry: Readiness assessment. Food Control 2021, 121, 107661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnassi, M.; El Haiba, M. Implications of the Russia-Ukraine war for global food security. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Li, X.; Jia, N.; Feng, F.; Huang, H.; Huang, J.; Fan, S.; Ciais, P.; Song, X.-P. The impact of Russia-Ukraine conflict on global food security. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 36, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Singh, S.; Bist, Y.; Kumar, Y.; Jan, K.; Bashir, K.; Jan, S.; Saxena, D.C. Carbon pricing and the food system: Implications for sustainability and equity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 150, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.J. The 10 Principles of Food Industry Sustainability; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; Available online: https://content.e-bookshelf.de/media/reading/L-3089653-83669bd2b0.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Prasanna, S.; Verma, P.; Bodh, S. The role of food industries in sustainability transition: A review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanowski, T. The Attitudes of Managers Towards the Concept of Sustainable Development in Polish Food Industry Enterprises. Environ. Prot. Yearb. 2020, 22, 622–634. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak, I.; Szajner, P. Challenges of Energy Management in the Food Industry in Poland in the Context of the Objectives of the European Green Deal and the “Farm to Fork” Strategy. Energies 2022, 15, 9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accenture. Zrównoważona Żywność w Polsce. Narodziny Masowego Rynku Jako Szansa dla Branży Spożywczej. 2021. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/content/dam/accenture/final/a-com-migration/manual/r3/pdf/pdf-158/Accenture-Sustainable-Food-Poland.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Melitz, M.J. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 2003, 71, 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeaple, S.R. A simple model of firm heterogeneity, international trade, and wages. J. Int. Econ. 2005, 65, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-Mercosur Accord: Le Libre-Échange au Prix des Enjeux Sociaux et Environnementaux. Available online: https://www.cncd.be/Accord-UE-Mercosur-Le-libre?lang=fr (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Terradas-Cobas, L.; Céspedes-Payret, C.; Calabuig, E.L. Expansion of GM crops, antagonisms between MERCOSUR and the EU. The role of R&D and intellectual property rights’ policy. Environ. Dev. 2016, 19, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asako, K. Environmental pollution in an open economy. Econ. Rec. 1979, 55, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M.C. Regulation, Factor Rewards, and International Trade. J. Public Econ. 1982, 17, 335–354. Available online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0047-2727(82)90069-X (accessed on 15 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gozlan, E.; Marette, S. Commerce international et incertitude sur la qualite des produits. Econ. Int. 2000, 81, 43–64. Available online: http://www.cepii.fr/IE/ei.asp?issue=81 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- van Berkum, S. Prospects of an EU-Mercosur Trade Agreement for the Dutch Agrifood Sector; LEI Report 2015–036; LEI Wageningen University & Research Centre: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Capie, F. Tariffs and Growth: Some Illustrations from the World Economy, 1850–1940; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, W.H. Protection in Various Countries: Germany; King & Son Orchard House Westminster: London, UK, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- List, F. Das Nationale System der Politischen Ökonomie; Zweite Auflage; Verlag von G. Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, A. Does Import Protection Act as Export Promotion? Evidence from United States. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1994, 46, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiotto, L.; Echaide, J. Analysis of the Agreement Between the European Union and the Mercosur. The Greens/EFA in the European Parliament. PowerShift e.V. 2019. Available online: https://www.annacavazzini.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Study-on-the-EU-Mercosur-agreement-09.01.2020-1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Karatepe, I.D.; Scherrer, C.; Tizzot, H. Mercosur-EU Agreement: Impact on Agriculture, Environment and Consumers; ICDD Working Papers No. 27; Kassel University Press: Kassel, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltensperger, M.; Dad, U. The European Union-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement: Prospects and Risks. Policy Contribution Issue n˚11 | September 2019. pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28500 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Copeland, B.; Taylor, S. North-South trade and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 755–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A. Model Zrównoważenia Przedsiębiorstwa; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej: Wrocław, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luderer, B.; Nollau, V.; Vetters, K. Mathematical Formulas for Economists; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, P.H. The Cobb-Douglas Production Function Once Again: Its History, Its Testing, and Some New Empirical Values. J. Political Econ. 1976, 84, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L.; Han, Y. A modified Cobb-Douglas production function model and its application. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2014, 25, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labini, P.S. Why the interpretation of the Cobb-Douglas production function must be radically changed. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 1995, 6, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community, Eurostat Methodologies and Working Papers 2008; Eurostat NACE Rev. 2; EUROSTAT: Luxembourg, 2008; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5902521/KS-RA-07-015-EN.PDF (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- StatSoft Polska. Sp. z o.o. 2025 Kit Plus version 5.1.0. Available online: www.statsoft.pl (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- CSO. The Agricultural Census 2020. Warsaw 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/agriculture-forestry/agricultural-census-2020/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Prus, P. Sustainable farming production and its impact on the natural environment-case study based on a selected group of farmers. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference Rural Development 2017: Bioeconomy Challenges, Aleksandras Stulginskis University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 23–24 November 2017; Raupeliene, A., Ed.; VDU Research Management System: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2017; pp. 1280–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Prus, P. Farmers’ Opinions about the Prospects of Family Farming Development in Poland. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference “Economic Science for Rural Development”, Jelgava, Latvia, 9–11 May 2018; pp. 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro, M.; Villarreal, F. Foreign Investment in Agriculture in MERCOSUR Member Countries; TKN REPORT; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://www.iisd.org/publications/report/foreign-investment-agriculture-mercosur-member-countries (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Śmietanka, T. Polityka Społeczna Gminy Jako Czynnik Rozwoju Lokalnego (Na Przykładzie Gmin Miejsko-Wiejskich Grójec, Kozienice, Szydłowiec); Związek Miast Polskich: Poznań, Poland; Kozienice, Poland, 2016; Available online: https://www.miasta.pl/uploads/document/content_file/345/Polityka_spo_eczna_gminy_jako_czynnik_rozwoju_lokalnego_-na_przyk_adzie_gmin_miejsko-wiejskich_Gr_jec__Kozienice__Szyd_owiec_-_dr_Tomasz__mietanka__grudzien_2016.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kosior, K. The Advancement of Digitalization Processes in Food Industry Enterprises in the European Union. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2022, 371, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, M.; Pinna, C.; Tonelli, F.; Terzi, S.; Sansone, C.; Testa, C. Food industry digitalization: From challenges and trends to opportunities and solutions. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.O.; Durakbasa, N.; Erdol, H.; Berber, T.; Bas, G.; Sevik, U. Implementation of Digitalization in Food Industry. In DAAAM International Scientific Book; 2017; Chapter 8; pp. 91–104. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/UgurSevik/publication/321248464_Implementation_of_Digitalization_In_Food_Industry/links/5a66092faca272a158205df5/Implementation-of-Digitalization-In-FoodIndustry.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Łukiewska, K. Innovation and Industry 4.0 in building the international competitiveness of food industry enterprises: The perspective of food industry representatives in Poland. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2024, 10, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykaczewski, G. Zielona Transformacja Branży Rolno-Spożywczej. Szansa Czy Zagrożenie dla Konkurencyjności Polskiego Sektora? Raport Banku Pekao. 2024. Available online: https://media.pekao.com.pl/pr/844233/raport-banku-pekao-zielona-transformacja-branzy-rolno-spozywczej-a-konkurencyjnosc-polskiego-sektora (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Grześ, A. Outsoursing in Shaping Employment and Labour Costs and Productivity in Enterprises; University of Białystok Publishing House: Białystok, Poland, 2017; Available online: https://repozytorium.uwb.edu.pl/jspui/handle/11320/10199 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D.; Falkowski, J. Restructuring of the dairy sector in Poland—Causes and consequences. Rocz. Nauk. Rol. Ser. G, Èkon. Rol. 2007, 94, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, M. Competition and efficiency on the Polish banking market against the background of structural and technological changes. Mater. Stud. 2005, 192, 1–45. Available online: https://static.nbp.pl/publikacje/materialy-i-studia/ms192.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Behar, J. Cooperation and Competition in a Common Market; Studies on the Formation of MERCOSUR; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stender, F. MERCOSUR in gravity: An accounting approach to analyzing its trade effects. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2017, 15, 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, R. (Ed.) The Food Industry in Poland; ING Corporate Banking: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżanowska, K. Ekonomiczno-Społeczne Uwarunkowania Innowacji w Zespołowym Działaniu w Rolnictwie; SGGW Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Available online: https://www.ieif.sggw.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Ekonomiczno-spoleczne_KrzyzanowskaK.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

| Specification | 2002 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 = 100 | |||

| Number of enterprises | 7036 | 4914 | 69.8 |

| small | 5426 | 3646 | 67.2 |

| medium | 1318 | 988 | 75.0 |

| large | 292 | 280 | 95.9 |

| Employment per company | 55 | 75 | 136.4 |

| small | 18 | 19 | 105.1 |

| medium | 104 | 105 | 101.2 |

| large | 528 | 696 | 131.9 |

| Production per company | 12.3 | 41.5 | 336.3 |

| small | 2.9 | 6.6 | 229.3 |

| medium | 22.1 | 55.4 | 250.2 |

| large | 143.6 | 446.3 | 310.8 |

| Qt = aKtαLtβ | lnQt = lna+ αlnQt + βlnQt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Parameters | Standard Error | p | Model Parameters | p | Standard Error |

| const a = 2.2013 | 1.199233 | 0.08212 ** | const lna = 0.8367 | 0.04784 ** | 0.393178 |

| α = 0.8757 | 0.243788 | 0.00194 *** | α = 0.8841 | 0.00015 *** | 0.195421 |

| β = 0.1063 | 0.236886 | 0.65869 | β = 0.0742 | 0.70820 | 0.187832 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szajner, P.; Pawłowska-Tyszko, J.; Łopaciuk, W.; Kosior, K. Sustainable Concentration in the Polish Food Industry in the Context of the EU-MERCOSUR Trade Agreement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125640

Szajner P, Pawłowska-Tyszko J, Łopaciuk W, Kosior K. Sustainable Concentration in the Polish Food Industry in the Context of the EU-MERCOSUR Trade Agreement. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125640

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzajner, Piotr, Joanna Pawłowska-Tyszko, Wiesław Łopaciuk, and Katarzyna Kosior. 2025. "Sustainable Concentration in the Polish Food Industry in the Context of the EU-MERCOSUR Trade Agreement" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125640

APA StyleSzajner, P., Pawłowska-Tyszko, J., Łopaciuk, W., & Kosior, K. (2025). Sustainable Concentration in the Polish Food Industry in the Context of the EU-MERCOSUR Trade Agreement. Sustainability, 17(12), 5640. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125640