1. Introduction

Persistent disparities between urban and rural regions remain a defining feature of many developing economies, with insufficient impetus for sustainable employment, defined here as inclusive, long-term, and regionally balanced job creation. Labor migration from rural to urban areas continues at scale, driven by uneven access to employment, infrastructure, and services. Classical development models, notably the Lewis dual-sector theory, predict that such migration will gradually dissolve urban–rural divisions by reallocating surplus rural labor to more productive urban sectors [

1,

2]. Yet this convergence has not materialized. Instead, in countries like China, rural–urban migration has entrenched spatial inequalities, drained rural labor pools, and stalled rural industrial upgrading [

3].

Scholars and policymakers have long debated how to break this cycle. Traditional policy prescriptions—focused on industrial relocation or rural subsidies—have had mixed success. Recent research points to digital technologies, particularly rural e-commerce, as a potential catalyst for reversing rural decline [

4]. E-commerce lowers transaction costs, expands market access, and stimulates both industrial diversification and entrepreneurial activity [

5,

6]. It helps overcome structural bottlenecks in traditional industries, revitalize momentum for sustainable development, and mitigate the one-way flow of labor from rural to urban areas. In this context, rural e-commerce is increasingly recognized as a vital component of broader sustainability transitions, by fostering inclusive digital economies, promoting local employment, and supporting regionally balanced growth. In China, the rapid expansion of Taobao villages illustrates this trend: by 2022, such villages spanned 28 provinces and 180 cities, reaching a total of 7780—an increase of 757 from the previous year, representing 11% growth. The number of Taobao towns rose to 2429, up by 258 (12%). These developments underscore the potential of digital infrastructure to re-anchor economic activity in rural regions [

7].

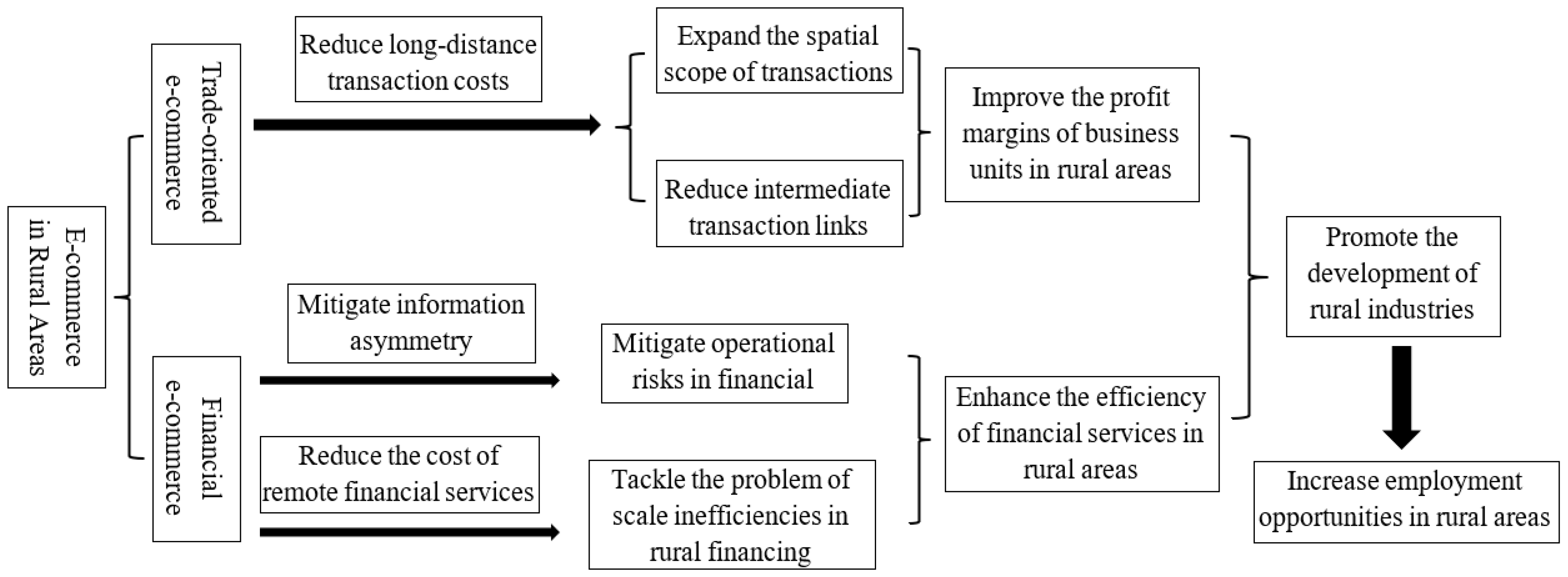

Despite growing interest, substantial knowledge gaps remain. Most existing studies emphasize trade-oriented e-commerce and rarely consider the role of financial e-commerce, such as digital payments or online credit systems, in shaping local labor markets. Furthermore, the effectiveness of rural e-commerce may hinge on context-specific factors, including regional economic capacity and institutional readiness—the preparedness of local institutions to support and facilitate digital commerce—yet these factors are often overlooked. Empirical work remains limited by narrow measurement tools, typically relying on the count of e-commerce-designated villages, which fail to capture the breadth and complexity of rural digital transformation [

8]. Additionally, existing literature largely neglects the nuanced connections between different e-commerce modalities—especially financial e-commerce—and sustainable employment. Sustainability, explicitly defined here as inclusive and enduring employment growth, remains inadequately addressed. Most empirical work narrowly quantifies rural e-commerce through counts of designated villages, overlooking broader economic complexities and regional variations in institutional capacity. Addressing these gaps, this study empirically explores the combined impacts of financial and trade-oriented e-commerce on rural employment sustainability, considering distinct regional conditions and economic capacities. By adopting refined indicators and comprehensive regional analyses, this research elucidates how diverse e-commerce types affect rural employment trajectories, emphasizing inclusive and enduring economic opportunities.

Specifically, this study addresses three critical research questions: (1) What mechanisms enable financial e-commerce to sustainably enhance rural employment? (2) How do the employment impacts of rural e-commerce differ across regions with varying economic capacities? (3) How can the measurement of rural e-commerce development be optimized to capture its multifaceted and sustainability-oriented nature?

To answer these questions, this study adopts an integrative theoretical framework that encompasses both trade-oriented and financial e-commerce, thereby clarifying their respective mechanisms in promoting rural employment. It further considers regional economic heterogeneity to delineate how local conditions modulate e-commerce’s effectiveness. Methodologically, this study introduces refined, multidimensional indicators that incorporate measures of both trade and financial e-commerce, enhancing empirical precision. Employing a comprehensive panel dataset from 28 Chinese provinces spanning 2012–2020, this research utilizes a two-way fixed effects regression model to robustly quantify e-commerce’s employment impacts.

This study contributes to this agenda by exploring rural e-commerce not only as a commercial innovation but also as a mechanism for promoting sustainable livelihoods, reducing spatial inequality, and enabling local resilience in the face of urban-centric economic pressures. It advances the literature by broadening both theoretical and empirical perspectives. First, it incorporates financial e-commerce into the analytical framework and introduces refined indicators that capture developments in both trade and financial domains. Second, it examines how the employment effects of rural e-commerce vary across regions with differing economic capacities, thereby uncovering context-dependent constraints. Third, it assesses whether rural e-commerce can offset labor outflows typically driven by urban economic growth, through a comparative analysis of regional employment patterns.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature relevant to rural e-commerce and local employment.

Section 3 develops the theoretical framework and articulates key hypotheses, focusing on the role of rural e-commerce and the heterogeneity of its impacts.

Section 4 introduces the data, defines core variables, and details the empirical model.

Section 5 presents the empirical findings, including descriptive analyses, baseline regressions, robustness checks, and heterogeneity analysis.

Section 6 discusses the broader implications of the results, highlights contributions to theory and policy, addresses limitations, and

Section 7 concludes with directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

To address the excessive migration of rural labor to urban centers in developing countries, it is essential to strengthen the momentum for sustainable development in rural areas by promoting local industries, thereby encouraging return migration for entrepreneurship and employment. An emerging body of research identifies rural e-commerce as a potential catalyst for this transformation, offering new employment opportunities and stimulating local entrepreneurship [

4]. By lowering transaction costs and connecting remote communities to broader markets, e-commerce activates decentralized economic development and improves the local business environment. Crucially, it creates both manual and knowledge-intensive jobs, reshaping the rural labor market [

5,

6]. This transition supports inclusive and regionally balanced development, contributing to the sustainability goals of reducing inequality and enhancing local livelihoods.

2.1. Rural E-Commerce Increases Labor Income

Rural e-commerce reduces outward migration—especially among young adults—and has emerged as an effective policy tool to counter rural depopulation [

7]. Survey data on China’s floating population show that the development of rural e-commerce increases return migration intentions by 9.6% [

8]. A key driver of this shift is that rural e-commerce contributes meaningfully to farmers’ incomes, helping to narrow the urban–rural income gap [

9,

10]. By promoting market integration [

11] and enabling income diversification [

12], e-commerce shifts income sources from external wage labor and traditional farming to local non-agricultural employment [

13]. These dynamics enhance rural resilience and economic stability—priorities at the heart of sustainable development policy. The Chinese government’s E-commerce into Rural Areas Demonstration policy has shown significant income effects [

14], strengthened households’ ability to withstand poverty shocks [

15], and produced sustained reductions in poverty incidence, particularly in remote regions [

16]. Higher local earnings from non-agricultural jobs further incentivize workers to remain in or return to their hometowns. Empirical findings indicate that for every 1% increase in e-commerce-related household income, the likelihood of working outside the home decreases by 0.6% [

13].

2.2. Rural E-Commerce Stimulates Employment

Two key pathways underpin the employment effects of rural e-commerce: industrial upgrading and entrepreneurial activation. On the industrial side, e-commerce, by enabling technological empowerment and demand-driven growth, spurs transformation of the rural industrial structure [

10]. It creates new occupations—including e-store operators, logistics managers, and customer service agents—and stimulates the growth of supporting sectors such as logistics, packaging, and finance, thereby expanding employment opportunities in roles like drivers and warehouse personnel [

10,

17]. By reducing transaction costs and enabling technology diffusion, e-commerce also indirectly enhances other rural industries, expanding employment capacity [

18]. E-commerce platforms allow farmers to bypass intermediaries and engage directly with national and even global markets, reducing search and transaction costs, increasing volumes and prices, and boosting profitability [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Beyond agriculture, e-commerce supports the development of rural secondary and tertiary industries, creating local non-farm jobs through commercial agglomeration and factor pooling—including capital, talent, and technology—at the county level [

22,

23]. Case studies in China’s old revolutionary base areas confirm that e-commerce significantly promotes local non-farm employment [

24]. These processes contribute to the structural transformation and diversification of rural economies, a key tenet of sustainability-focused rural revitalization. The integration of agriculture, processing, and services further enhances the resilience and stability of rural employment [

25].

2.3. Rural E-Commerce Fosters Entrepreneurship

On the entrepreneurship front, e-commerce and digital technologies reduce entry barriers, increase the probability of rural entrepreneurship, and improve entrepreneurial outcomes [

26]. E-commerce alleviates key constraints—such as information gaps, capital shortages, and limited technical or social capital—while expanding market access, thus lowering entrepreneurial risk [

27,

28]. Empirical evidence shows that rural e-commerce significantly boosts both individual entrepreneurial engagement and regional entrepreneurial activity [

29,

30]. Notably, it has been found to markedly raise the rate of female entrepreneurship in rural areas, particularly by lowering barriers for individuals with limited human capital in non-high-income segments of the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) [

31,

32]. This digital empowerment of marginalized groups, including women, aligns with global sustainability priorities centered on equity and inclusive innovation.

Despite these advances, three major gaps remain. First, most studies narrowly focus on trade-oriented platforms, overlooking the role of financial e-commerce—such as digital payments and online credit—in enabling rural industrial viability. Second, the literature has insufficiently addressed the structural conditions shaping e-commerce outcomes, including regional disparities in economic development. Third, prevailing models, grounded in classical dual-sector theory, often assume the absence of modern industry in rural areas and predict unidirectional labor flows toward cities. Yet, the rise of digital technologies may allow modern sectors to emerge within rural economies, potentially reversing traditional migration patterns—an issue that warrants further scrutiny. Addressing these limitations is essential for understanding how rural e-commerce can serve not only as a market tool but as an enabler of long-term sustainable development. This study addresses these limitations by incorporating financial e-commerce into the conceptual framework and developing a multidimensional index to capture the scope of rural e-commerce. It also examines how structural heterogeneity conditions employment outcomes, offering a more context-sensitive account of digital inclusion in rural labor markets. By doing so, it aims to contribute new empirical and theoretical insights to sustainability science, particularly in relation to rural development, digital transformation, and inclusive economic growth.

5. Empirical Analysis Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the primary variables. After standardization, the mean value of rural laborers working within county boundaries (LE) is 0.3089, with a maximum of 0.9383 and a minimum of 0.0099, indicating substantial variation in intra-county labor mobility across 28 provinces over a nine-year period. The composite index for rural e-commerce development (RE) has a mean of 0.0727, ranging from 0.0028 to 0.6851, also reflecting marked changes in rural e-commerce over the same period. Among the control variables, rural population (RP) exhibits high variance, suggesting significant interprovincial differences in rural demographic distribution. In contrast, the relatively low variance in educational attainment (EA) indicates a concentration in education levels and reflects the overall stability of rural labor quality.

5.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

To estimate the panel data model, we begin by determining whether a fixed effects or random effects specification is appropriate. As shown in

Table 4, the Hausman test conducted using Stata MP-64 yields a

p-value of 0.000, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis in favor of the fixed effects model. Next, to assess the presence of time-specific effects, we introduce year dummy variables.

Table 4 reports the joint significance test of these time dummies, which indicates a

p-value below 0.1. This strongly rejects the null hypothesis of no time effects, suggesting the existence of significant temporal variation. Consequently, a two-way fixed effects model is adopted, incorporating both individual and time fixed effects. Cluster-robust standard errors are used to account for potential heteroskedasticity.

Table 5 presents the results of stepwise regressions under a two-way fixed effects model. Column (1) shows that, even without any control variables, rural e-commerce development has a statistically significant positive effect on the local employment of rural labor. Specifically, participation in e-commerce is associated with a 7.6% increase in the likelihood of rural laborers securing employment within their home counties. Columns (2) through (5) sequentially introduce control variables, and across all specifications, the coefficient on rural e-commerce development remains positive and statistically significant. Column (6) reports the full model, incorporating all control variables and fixed effects. In this specification, the coefficient on rural e-commerce development is 0.1, with a p-value below 0.01, indicating significance at the 1% level. This result confirms that, after accounting for province and year fixed effects as well as a set of relevant controls, rural e-commerce development exerts a robust and significant positive effect on local labor employment. Specifically, participation in e-commerce is associated with a 10% increase in the probability that rural workers obtain employment within their home counties. These findings provide empirical support for H

1: rural e-commerce promotes the local employment of rural labor, regardless of whether spatial, temporal, or other relevant factors are controlled for.

Among the control variables, the urban–rural income ratio and rural population are both significantly and negatively associated with local labor employment. A wider income gap between urban and rural areas incentivizes rural workers to migrate to urban centers in search of higher wages and better living standards. Urban areas generally offer more diversified industries and employment opportunities with higher pay and career prospects. In contrast, rural economies tend to be less diversified, with limited employment options. A surplus of rural population can result in an excess labor supply, which in turn reduces employment probability and income levels in rural areas. Overpopulation in rural regions may also place pressure on natural resources, hindering agricultural production and broader rural economic development. Resource constraints further limit the expansion of emerging sectors such as rural e-commerce, thereby reducing local job creation. Moreover, an increasing rural population imposes greater demand on infrastructure. Without sufficient infrastructure investment, issues such as traffic congestion, water and electricity shortages, and poor communication services may arise, diminishing quality of life and prompting labor migration to better-equipped urban centers.

Educational attainment, by contrast, is positively associated with local labor employment. Rural workers with higher education levels are more competitive in local labor markets, more innovative, and better positioned to participate in the rural e-commerce sector. Agricultural labor productivity and the relative rural poverty rate are negatively associated with local labor employment. Rising agricultural productivity reduces the demand for agricultural labor. While increased productivity may raise the income of those remaining in agriculture, it may also reduce the incentive for labor to shift into non-agricultural sectors. In regions with high relative poverty, low levels of economic development and industrialization constrain employment opportunities. Additionally, low skill levels among rural laborers in these areas may prevent them from meeting the requirements of non-agricultural jobs, thereby limiting their capacity to engage in local employment transitions.

5.3. Robustness Check

5.3.1. Alternative Variable Approach

To ensure the reliability of the empirical findings and reduce the likelihood that results are driven by the choice of a specific variable, a robustness check is conducted by replacing the main explanatory variable—rural e-commerce development level (RE)—with an alternative proxy: the standardized number of Taobao Villages (TB). As displayed in

Table 6, although the estimated coefficients differ slightly in magnitude between the original and the alternative specifications, the signs of the coefficients remain consistent, and both are statistically significant at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. Furthermore, the models exhibit similar levels of explanatory power. These results indicate that the analysis is robust and the conclusions are reliable.

5.3.2. Lagged Explanatory Variable Approach

To further test the robustness of the model, we re-estimate the regression using a one-period lag of the rural e-commerce development level (RE) as the explanatory variable. As demonstrated in

Table 7, the lagged variable (L.RE) remains statistically significant at the 5% level in explaining the intra-county employment of rural labor. This robustness check helps to mitigate potential endogeneity concerns arising from reverse causality, namely, the possibility that current labor mobility might influence the level of rural e-commerce development.

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

To explore regional heterogeneity, the sample is divided into four subgroups: eastern, northeastern, central, and western regions of China. The regression results are presented in

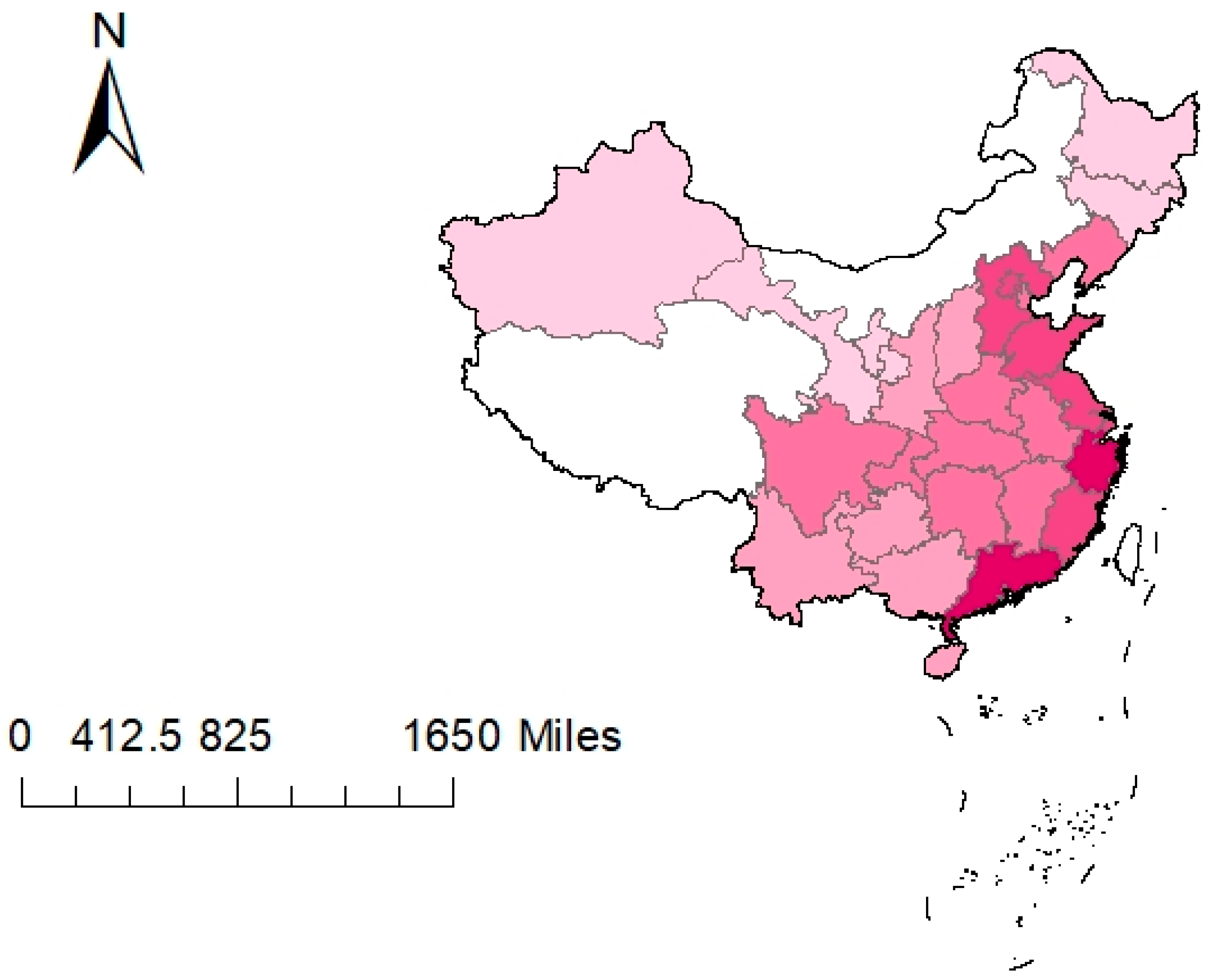

Table 8. At the 1% significance level, the development of rural e-commerce in eastern and central China has a statistically significant impact on intra-county labor mobility. In contrast, rural e-commerce in western China exhibits a significantly negative association with local labor transfer, while no statistically significant effect is observed in the northeastern region. These regional disparities likely stem from a combination of factors.

First, the level of economic development varies markedly across regions. The eastern region, with its mature industrial system and advanced economy, provides fertile ground and ample market demand for the growth of rural e-commerce. Central China has also witnessed rapid economic progress in recent years, underpinned by robust industrial and service sector growth. Conversely, the western region lags in economic development and has a relatively limited market scale—conditions that constrain the viability of rural e-commerce, which depends on sufficient consumer demand. The northeast, characterized by a narrow industrial base dominated by traditional heavy industry, faces structural economic challenges. These conditions inhibit the expansion of rural e-commerce and diminish its capacity to facilitate proximate labor transfers.

Second, disparities in institutional support and infrastructure development further contribute to the uneven landscape. Eastern and central provinces have taken the lead in e-commerce innovation and rural digitization. For instance, Guangdong and Fujian have established comprehensive agricultural and rural big data platforms, integrating datasets on land, population, and industry to enable cross-sectoral coordination. Zhejiang has launched a dedicated digital rural development fund and was the first province to be designated a national model for digital villages, leveraging technologies such as the “Zhe Nong Code” for product traceability and rural governance. Similarly, provinces such as Anhui and Hunan have introduced low-interest “digital village loans” to support smart agriculture and rural e-commerce ventures. These policy and infrastructural advances have created favorable conditions for rural e-commerce in these regions.

As a result of these multidimensional factors, regional disparities in rural e-commerce development persist, with the eastern region exhibiting the highest levels of advancement, followed by the central region (see

Figure 2). Regions with more advanced rural e-commerce development tend to exhibit stronger effects in promoting local employment. Taken together, the results from the heterogeneity analysis provide empirical support for H

2, indicating that the effects of rural e-commerce on local labor mobility vary substantially across regions.

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Findings

This study offers a theoretical and empirical investigation into how rural e-commerce development promotes local employment in developing regions. On the theoretical front, we distinguish between two types of e-commerce: trade-oriented platforms, which reduce transaction costs for goods and services in rural areas, and finance-oriented platforms, which alleviate credit constraints faced by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Both forms contribute to structural transformation and the diversification of rural economies, thereby reinforcing the broader goals of sustainable development. Building on this framework, we conduct an empirical analysis using a balanced panel dataset covering 28 provincial-level regions in China from 2012 to 2020. We refine the measurement of rural e-commerce development by incorporating both trade and financial e-commerce indicators. A two-way fixed-effects model is employed to examine the impact of e-commerce on labor retention. The key findings are as follows.

First, we find that rural e-commerce development significantly enhances intra-county retention of rural labor. This effect persists across various model specifications, including stepwise regressions, alternative proxies for e-commerce intensity (e.g., number of Taobao Villages), and models controlling for endogeneity. These results are broadly consistent with prior studies highlighting the role of digital platforms in localizing economic opportunities [

14,

49]. Moreover, recent evidence from India and Indonesia suggests that digital platforms have catalyzed rural employment through enabling market access and supply chain integration for micro-entrepreneurs and farmers [

50]. Such international findings strengthen the generalizability of our results. Importantly, similar labor-retention and rural revitalization effects have been observed in other developing economies. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, studies of mobile money and digital marketplaces indicate enhanced resilience and labor participation, particularly among youth and women [

51,

52]. Likewise, evidence from Latin America indicates that platform economies can stimulate inclusive growth, provided sufficient institutional and infrastructural support is present [

53]. These international parallels suggest that the mechanisms we identify—enhanced information access, reduced transaction costs, and improved labor mobility—may represent generalizable pathways through which rural e-commerce can foster inclusive development. Critically, our findings suggest that this labor retention effect operates through three interlinked mechanisms: enhanced information access, reduced transaction costs, and improved labor mobility. First, e-commerce platforms lower information asymmetries by making market and financial information more accessible to rural producers, thereby enabling better decision-making and planning. Second, by reducing transaction costs related to logistics, negotiation, and market entry, digital platforms ease spatial constraints and make rural production and trade more viable. Third, e-commerce fosters the development of local agro-processing and service sectors—such as logistics and livestreaming-based sales—which broadens the scope of local employment opportunities and enhances labor mobility within rural economies. Our findings extend this literature by demonstrating a causal pathway from digital market access to labor retention—a relationship previously suggested but not rigorously established [

54]. This supports an emerging body of work positioning digital infrastructure as foundational to inclusive growth strategies [

55]. By illuminating these underlying mechanisms, our analysis underscores the role of e-commerce as a transformative infrastructure that restructures rural labor markets and revitalizes local economies. This reinforces the potential of digital infrastructure as a lever for anchoring populations and economic activity in rural areas—a critical dimension of equitable and place-based sustainability strategies.

Second, we identify pronounced regional heterogeneity in e-commerce effects. The positive impacts are concentrated in the eastern and central provinces, where digital infrastructure, market integration, and human capital are more advanced—corroborating evidence from recent regional case studies [

56,

57]. Conversely, the western region exhibits a negative association, while the northeastern region shows no significant effect. This divergence departs from the uniformly positive trends reported in earlier national-level studies [

58] and points to structural impediments—such as logistical bottlenecks and limited digital literacy—that may suppress e-commerce’s developmental potential in lagging areas. Analogous regional disparities have been reported in Kenya and Brazil, where the benefits of rural digitization are likewise contingent on pre-existing infrastructure and institutional readiness [

59,

60]. These findings emphasize the importance of spatial justice in digital transformation policies and highlight the risk of exacerbating regional inequalities in sustainability outcomes.

Third, the control variables underscore critical channels of rural labor mobility. Higher educational attainment is positively associated with local employment, supporting theories that human capital facilitates adaptation to digital economic modes [

61]. In contrast, larger rural populations and wider urban–rural income gaps are linked to out-migration, aligning with migration push-pull models [

62] and recent empirical findings in the Chinese context [

49]. These insights underscore how digital employment pathways are shaped by broader socio-demographic and institutional conditions—echoing core principles in sustainability science about the interdependence of economic, social, and technological systems. These dynamics align with current debates on digital inclusion and sustainable livelihoods, emphasizing the role of adaptive policy frameworks [

63]. Taken together, our findings resonate with a growing international consensus that rural digitalization, while promising, must be embedded within context-sensitive policies and adaptive governance frameworks to realize inclusive outcomes. Collectively, these findings affirm that rural e-commerce can function as a catalyst for inclusive development, but only when embedded within a broader framework of institutional readiness, human capability, and place-sensitive planning—core pillars of sustainable rural transformation.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study offers a theoretically grounded and empirically validated assessment of how rural e-commerce influences local employment dynamics across 28 Chinese provinces from 2012 to 2020. By integrating financial e-commerce into the analytical framework and examining regional heterogeneity, our findings extend and refine existing theories of digital inclusion, rural development, and structural transformation.

First, our conceptual framework advances prior literature by explicitly incorporating the role of financial e-commerce—an area largely neglected in existing scholarship that tends to emphasize product-based or trade-oriented platforms [

14,

64]. While earlier studies have highlighted the potential of e-commerce to connect rural producers with broader markets [

65], few have examined how digital financial services contribute to rural industrial viability. We demonstrate that financial e-commerce—especially credit provision via digital platforms—plays a crucial role in alleviating the financing constraints faced by rural SMEs, a finding aligned with but distinct from studies on fintech inclusion [

66]. This integrative perspective highlights the importance of inclusive digital finance as a sustainability enabler that supports SME resilience and inclusive economic growth.

Second, by disaggregating the employment effects of e-commerce across regions with differing levels of economic development, we uncover the contingent nature of digital inclusion. Previous research has broadly asserted the employment-enhancing effects of rural e-commerce [

57] yet has paid insufficient attention to the moderating role of local context. Our findings suggest that the benefits of e-commerce are not automatic; rather, they depend critically on enabling regional factors such as industrial capacity, digital infrastructure, and workforce skills. This insight challenges techno-centric narratives and reinforces the need for contextually grounded, equity-oriented strategies in digital development [

67].

Third, our results contribute to the refinement of classical dual economy theory [

1] by foregrounding the role of rural digital transformation. Traditional models envisage rural–urban migration as a unidirectional process driven by wage differentials and surplus labor. However, our empirical evidence suggests that digital industrialization in rural areas—particularly via e-commerce—can reverse or decelerate migratory flows by generating viable local employment. In doing so, we advance a more dynamic and recursive theory of rural–urban integration that aligns with contemporary sustainability paradigms focused on localized development and endogenous innovation [

68].

6.3. Generalization of Findings

Although this study is grounded in the institutional and developmental context of China, its findings have broader implications for other geographical and economic environments, particularly in developing and transitional economies undergoing digital transformation. The dual role of rural e-commerce—lowering transaction costs through trade-oriented platforms and easing credit constraints via finance-oriented platforms—is not unique to China. These mechanisms are structurally relevant in regions where traditional market access remains limited and where small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face chronic underfinancing.

The employment-retaining effects of rural e-commerce provide a model for achieving spatially balanced development—addressing urban congestion and rural marginalization simultaneously, a dual challenge faced by many economies in the Global South. As emerging economies expand internet penetration and mobile payment infrastructure, the employment effects documented here are likely to manifest under similar conditions of institutional support and technological readiness. Moreover, the identification of regional heterogeneity underscores the need for calibrated digital policies that reflect subnational variation—a concern equally relevant in federal or decentralized states such as India, Brazil, or Nigeria.

Finally, the mediating roles of education, population pressure, and income inequality provide further conceptual scaffolding for generalization. These variables are central to understanding the co-evolution of social structures and digital innovation—an approach that aligns with the systemic, cross-scalar perspective advocated in sustainability research. In this sense, the Chinese experience presented here serves not only as an empirical case but as a blueprint for advancing equitable, inclusive, and resilient digital development strategies.

6.4. Implications of Findings

The findings of this study carry broad and long-term implications across economic, industrial, and political dimensions, offering a strategic foundation for policymakers, development agencies, and digital platform stakeholders seeking to harness e-commerce for inclusive rural transformation.

Economically, the evidence that rural e-commerce promotes local labor retention provides a compelling argument for integrating digital infrastructure into rural development strategies. As governments worldwide confront the dual challenges of rural depopulation and urban overcrowding, digital platforms present a scalable mechanism to rebalance spatial labor distribution. This reflects the broader sustainability imperative of reducing territorial disparities while fostering endogenous development capacity.

Industrially, this study underscores e-commerce’s capacity to act as a lever for structural upgrading. The bifurcation between trade- and finance-oriented platforms points to differentiated pathways through which digital technologies can unlock productivity gains for rural enterprises. These pathways offer scalable solutions for transitioning from subsistence to diversified rural economies—a hallmark of long-term rural sustainability.

Politically, the regional disparities identified in e-commerce’s employment effects highlight the importance of adaptive governance. Policymakers must move beyond one-size-fits-all digital agendas to embrace region-specific interventions that address infrastructural deficits, human capital shortfalls, and institutional gaps. This reinforces the sustainability principle of policy coherence and multilevel governance in addressing spatial inequalities. Taken together, these implications reinforce the strategic relevance of rural e-commerce as a tool for equitable development.

6.5. Policy Recommendations

The empirical insights generated by this study suggest a series of actionable policy interventions aimed at amplifying the developmental potential of rural e-commerce. Each recommendation corresponds to a specific research finding and is grounded in the recognition that successful implementation requires not only technical capacity but also political will, institutional coordination, and sustained investment. These recommendations are informed by the principles of sustainable development—particularly digital inclusion, regional equity, and institutional adaptability.

First, given the finding that rural e-commerce significantly enhances intra-county labor retention, national and subnational governments should incorporate digital platform development into rural revitalization agendas. This entails expanding access to e-commerce infrastructure, subsidizing onboarding for rural producers, and supporting local digital service ecosystems. However, implementation faces two core challenges: first, the upfront cost of infrastructure development in low-density rural areas may deter private investment; second, digital exclusion—driven by low digital literacy—may limit participation. To address these challenges in line with sustainability goals, governments should pursue blended financing models involving public–private partnerships, development finance institutions, and local cooperatives. These models can channel resources toward last-mile connectivity and inclusive digital ecosystems. Simultaneously, integrating digital skills training into agricultural extension and vocational programs can bridge capability gaps and broaden rural engagement with platform economies. This aligns with the sustainability principle of human capital development as a foundation for equitable digital transitions.

Second, the pronounced regional disparities identified in this study—where eastern and central regions benefit disproportionately while western and northeastern provinces lag—call for a differentiated policy approach. Central authorities should empower provincial and local governments to design adaptive interventions that reflect specific structural constraints, such as weak logistics networks, low market density, or limited human capital. Yet this decentralized model introduces potential political and bureaucratic hurdles, including coordination failures and uneven policy execution. A sustainability-informed solution is to implement national performance-based funding mechanisms that reward evidence-based, region-specific strategies aimed at closing digital development gaps. These could be supported by digital development dashboards that benchmark regional progress and foster policy learning across jurisdictions. Pilot programs in structurally disadvantaged regions can also serve as scalable models for inclusive e-commerce development, ensuring that interventions are both cost-effective and equity-oriented.

Third, the finding that educational attainment enhances local employment underscores the importance of human capital as a mediating factor in rural digital development. Governments should therefore integrate digital literacy and entrepreneurial training into rural education systems, from secondary school curricula to adult learning modules. Additionally, policies that narrow the urban–rural income gap—such as fiscal transfers, targeted welfare programs, and local job creation incentives—can reduce migration pressure and strengthen place-based sustainability. To ensure policy coherence and stakeholder alignment, national digital economy strategies should be explicitly linked with rural education, social protection, and industrial planning frameworks. Strategic partnerships with platform firms can also help scale training programs and ensure curricular relevance, while community-based income support schemes tied to digital work may serve as effective transitional mechanisms.

6.6. Limitations and Future Research

This study, while offering robust insights into the relationship between rural e-commerce and local employment, is subject to several limitations. First, while this study draws on authoritative third-party statistical data and applies fixed-effects models with robustness checks, it does not incorporate primary data collection. The reliance on a cross-sectional research design further limits causal inference, raising concerns about potential endogeneity and omitted variable bias. As such, unobserved time-varying factors may still introduce residual bias. Moreover, the absence of qualitative insights limits the interpretative depth of the findings. Future research would benefit from field-based data collection, including interviews with rural entrepreneurs, local officials, and platform operators, to capture the nuanced, ground-level mechanisms through which rural e-commerce influences labor allocation. Complementary methodological approaches, such as quasi-experimental designs, natural experiments, or instrumental variable strategies, may further strengthen causal inference and enrich understanding of regional heterogeneity in digital development outcomes. Second, this study proposes two central hypotheses, with regional heterogeneity in the impact of rural e-commerce on employment interpreted as a function of broader economic development. While we did not explicitly model the roles of education, infrastructure, and digital literacy, these factors are acknowledged as key components of regional disparities and are discussed as underlying dimensions of economic development. Additional statistical analysis has been included to illustrate variation across regions in these enabling conditions. However, the specific moderating effects of such factors were not independently tested. Future research should formally examine these mechanisms to more precisely isolate the conditions under which e-commerce yields the greatest local benefit. Moreover, this study focuses on comparative analysis between more and less developed regions, highlighting broad regional disparities in rural e-commerce development and labor dynamics. However, it does not provide a granular exploration of the specific institutional, infrastructural, or socio-economic barriers facing less developed regions. Future research should undertake more targeted case studies in these areas to uncover localized constraints and inform tailored policy interventions aimed at fostering inclusive digital transformation. Finally, while gender was referenced in the literature review, this study does not disaggregate effects by gender or age—an omission that limits understanding of how rural e-commerce may differently affect women, youth, or marginalized groups. Future work should explicitly examine gendered dimensions of digital labor and entrepreneurship, especially in light of emerging evidence on the potential of platform economies to both empower and marginalize female participants.

7. Conclusions

This study provides causal evidence that rural e-commerce—both trade- and finance-oriented—enhances intra-county labor retention and mitigates rural out-migration by strengthening the local employment base, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). By unpacking regional heterogeneity, we show that digital platforms do not operate in a vacuum; their developmental effects are contingent upon local infrastructure, institutional capacity, and human capital. Importantly, we extend prevailing theories by integrating financial e-commerce into the analysis, revealing its critical role in alleviating SME credit constraints for rural SMEs and supporting their industrial viability—an aspect largely overlooked in existing literature. From a sustainability perspective, these findings underscore the importance of treating digital transformation as an embedded socio-technical process, rather than a purely technological fix. To fully harness the inclusive potential of rural e-commerce, we recommend targeted policy interventions including expanding last-mile digital infrastructure through blended public–private financing; integrating digital literacy into rural education and vocational training; and introducing incentive mechanisms for rural SMEs to engage with platform economies. Regional disparities demand adaptive governance, with performance-based funding to support context-specific strategies, especially in structurally disadvantaged areas. Ultimately, this study contributes to a more context-sensitive understanding of how digital technologies can advance sustainable rural transformation. By foregrounding the integrative role of financial e-commerce and highlighting the interplay between technology and local conditions, we not only challenge techno-deterministic narratives but also offer a dynamic framework for inclusive digital development. This encourages future scholarship and policy to focus not only on scaling digital access but also on embedding equity, resilience, and local agency into the architecture of platform-driven development.