Identifying Pandemic Stress-Vulnerable Social Groups in Selected Polish Cities: A Geospatial Approach to Building Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Objective and Research Questions

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Vulnerability of Cities to the Pandemic

2.2. Social Groups Vulnerable to Pandemic Stress

3. Methodology

3.1. Geosurvey

3.2. Data Analysis Methods

3.3. Characteristics of Respondents

4. Results

4.1. Subjective Stress Levels in the Analysed Cities

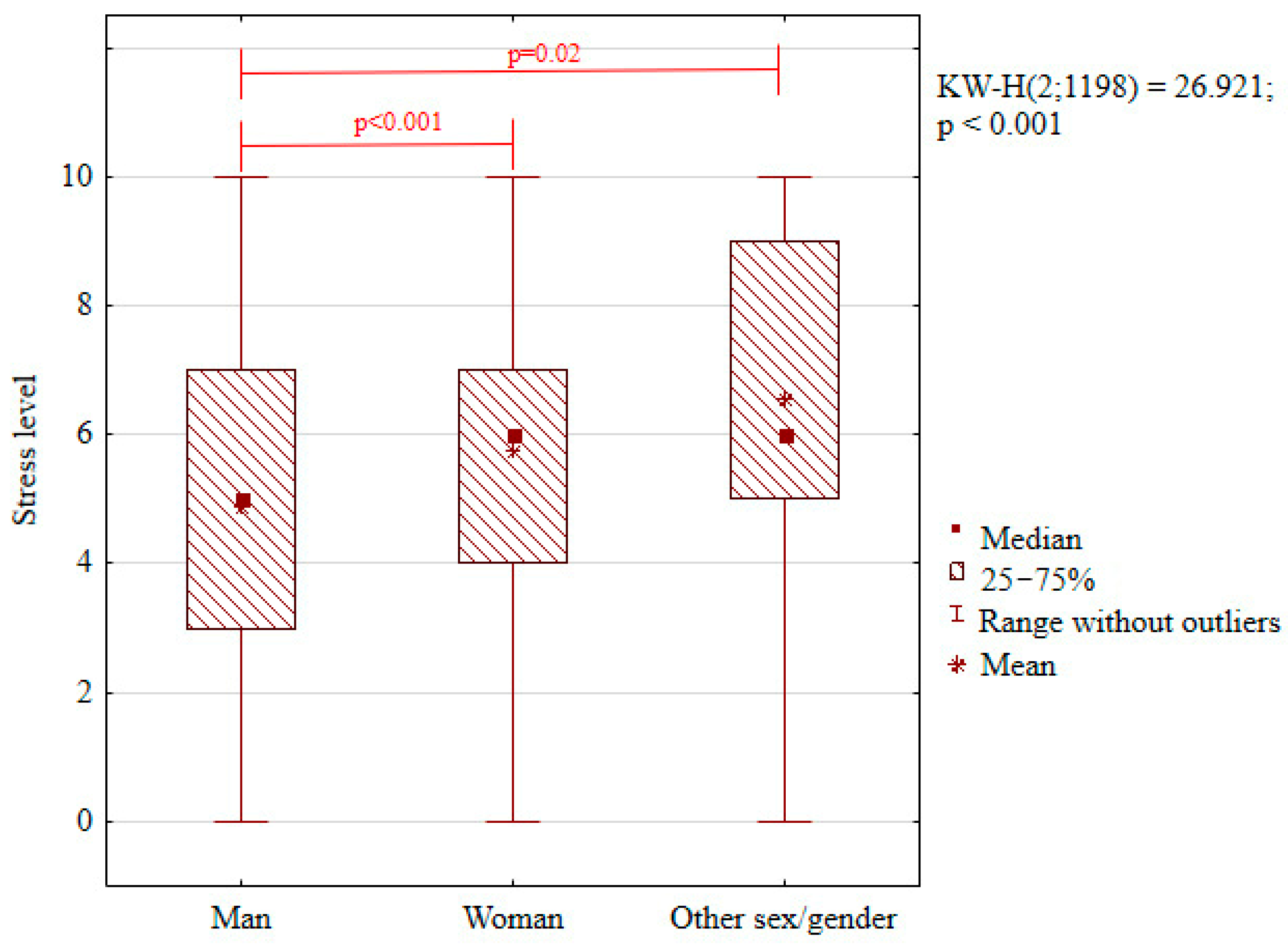

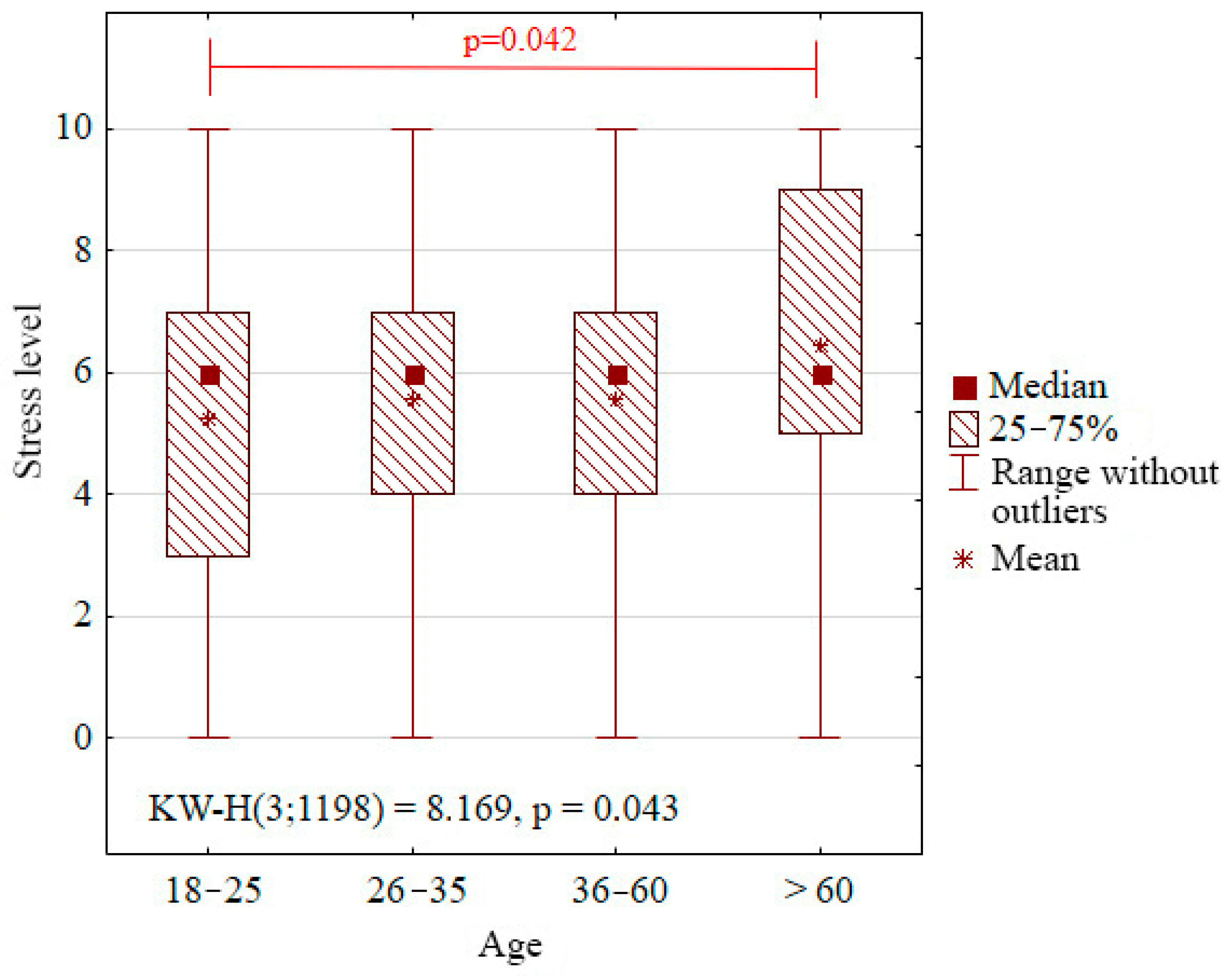

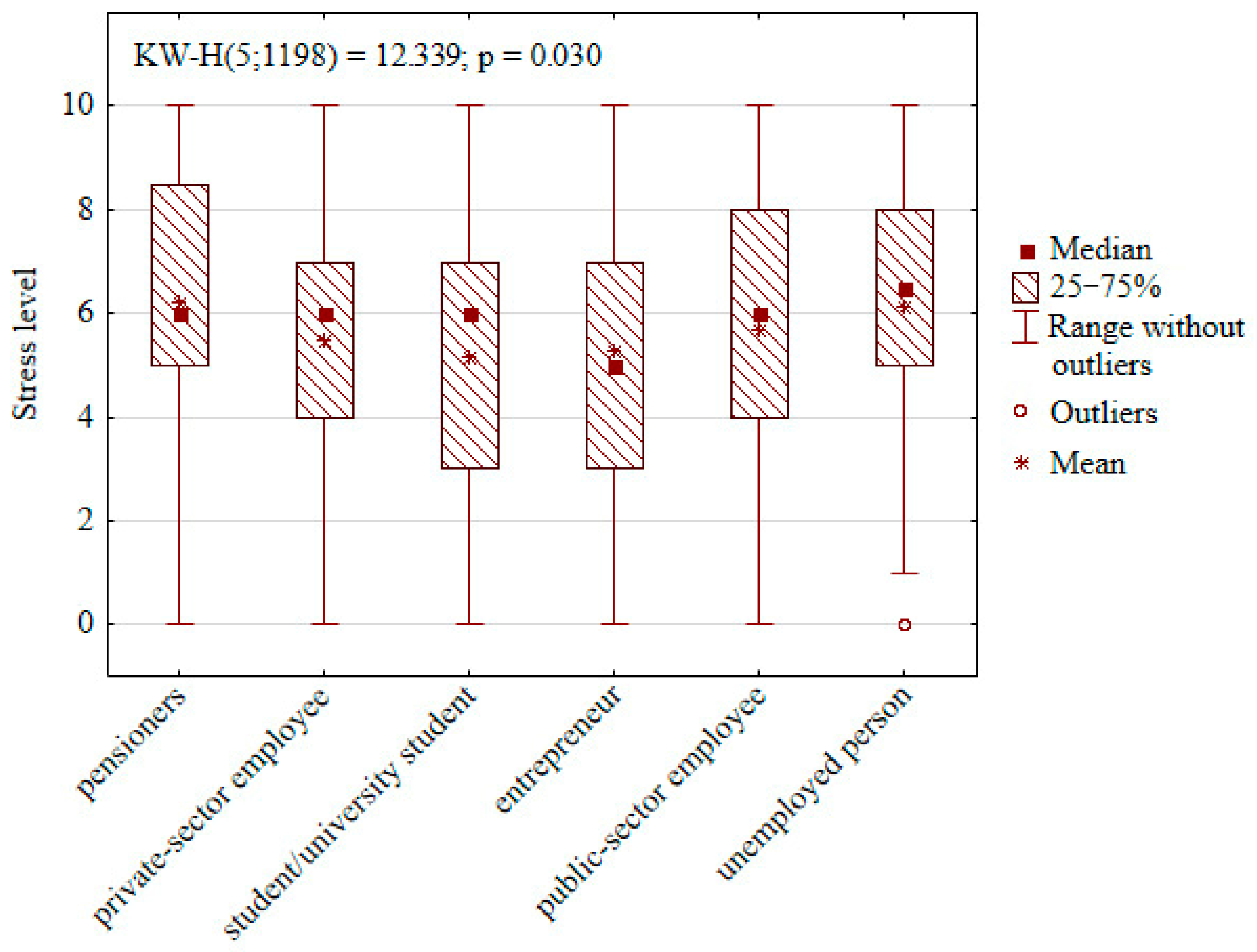

4.2. Analysis of Dependence Between Demographic Features of Respondents and Their Stress Level

- Red Lines Indicate Statistically Significant Differences Between Groups (Post Hoc Tests Following Kruskal–Wallis Test)

- Red Lines Indicate Statistically Significant Differences Between Groups (Post Hoc Tests Following Kruskal–Wallis Test)

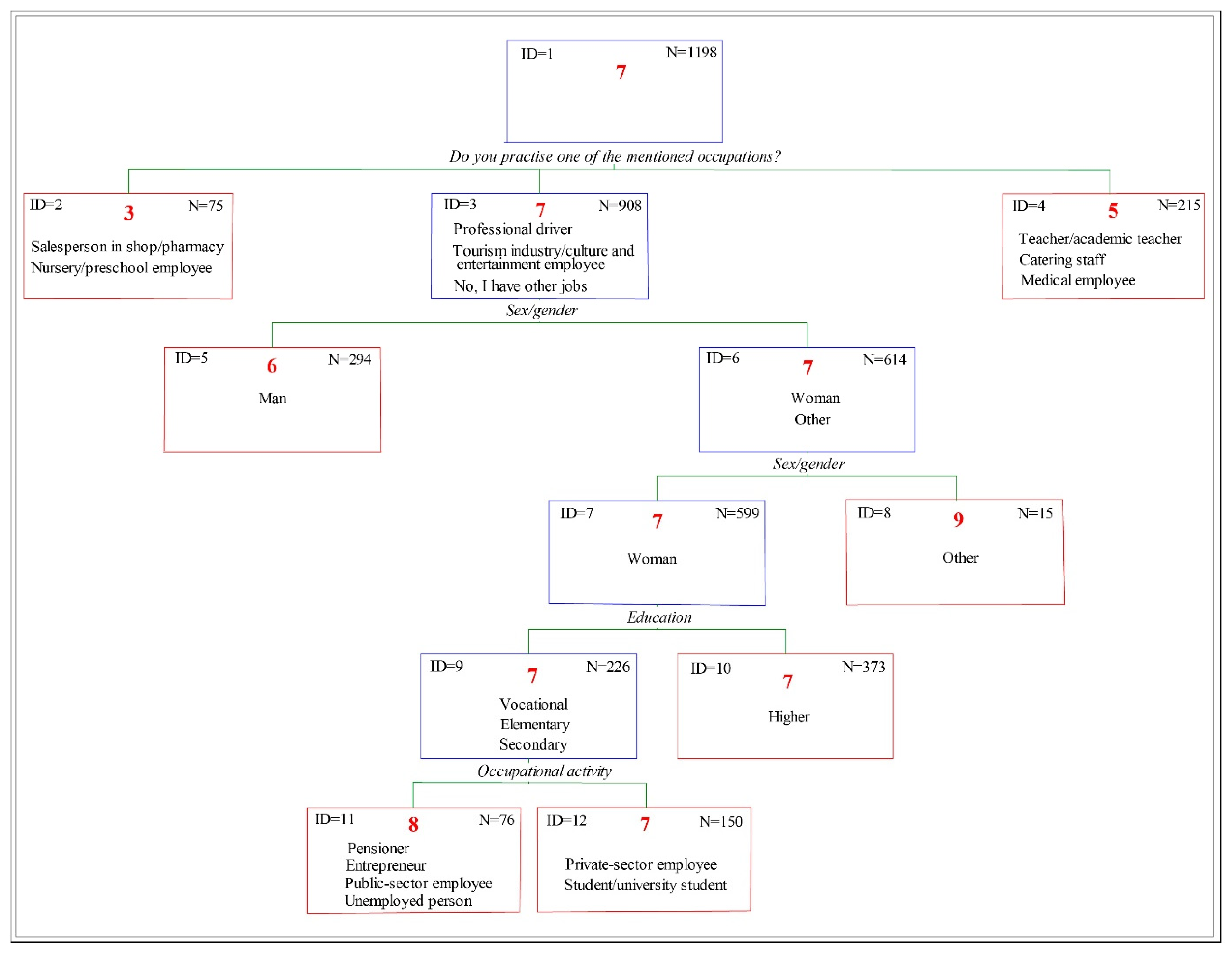

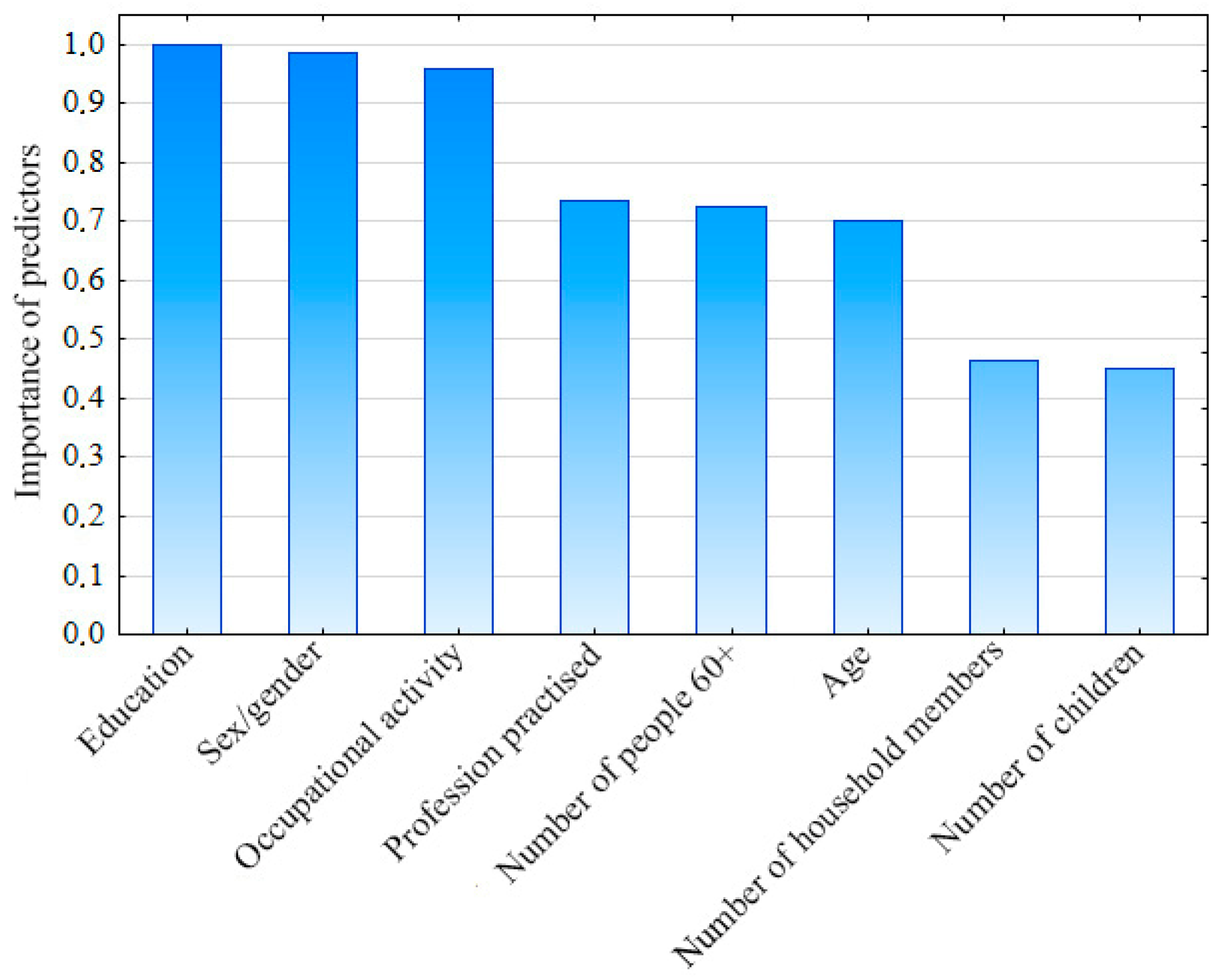

4.3. Identification of Stress-Vulnerable Groups by the CHAID Decision Tree

- First—includes salespeople and nursery and preschool staff (ID = 2, n = 25).

- Second—recognised as the most vulnerable, includes professional drivers, hotel and culture and entertainment employees, and also those practising other professions not mentioned in the geosurvey (ID = 3, n= 908).

- Third—composed of teachers, academic staff, medical personnel, and catering staff (ID = 4, n = 215).

4.4. Predicting Vulnerable Group Status: Logistic Regression Results

- Gender: Males had significantly lower odds of being in the stress-vulnerable group compared to females and individuals of other genders (odds ratio (OR) = 0.51; p = 0.015), suggesting that men were approximately 49% less likely to report high stress levels.

- Profession practised: Those employed in the tourism, culture, and entertainment sectors had higher odds of being in the stress-vulnerable group compared to the reference occupation category (OR = 2.42; p = 0.018), indicating that they were more than twice as likely to report elevated stress.

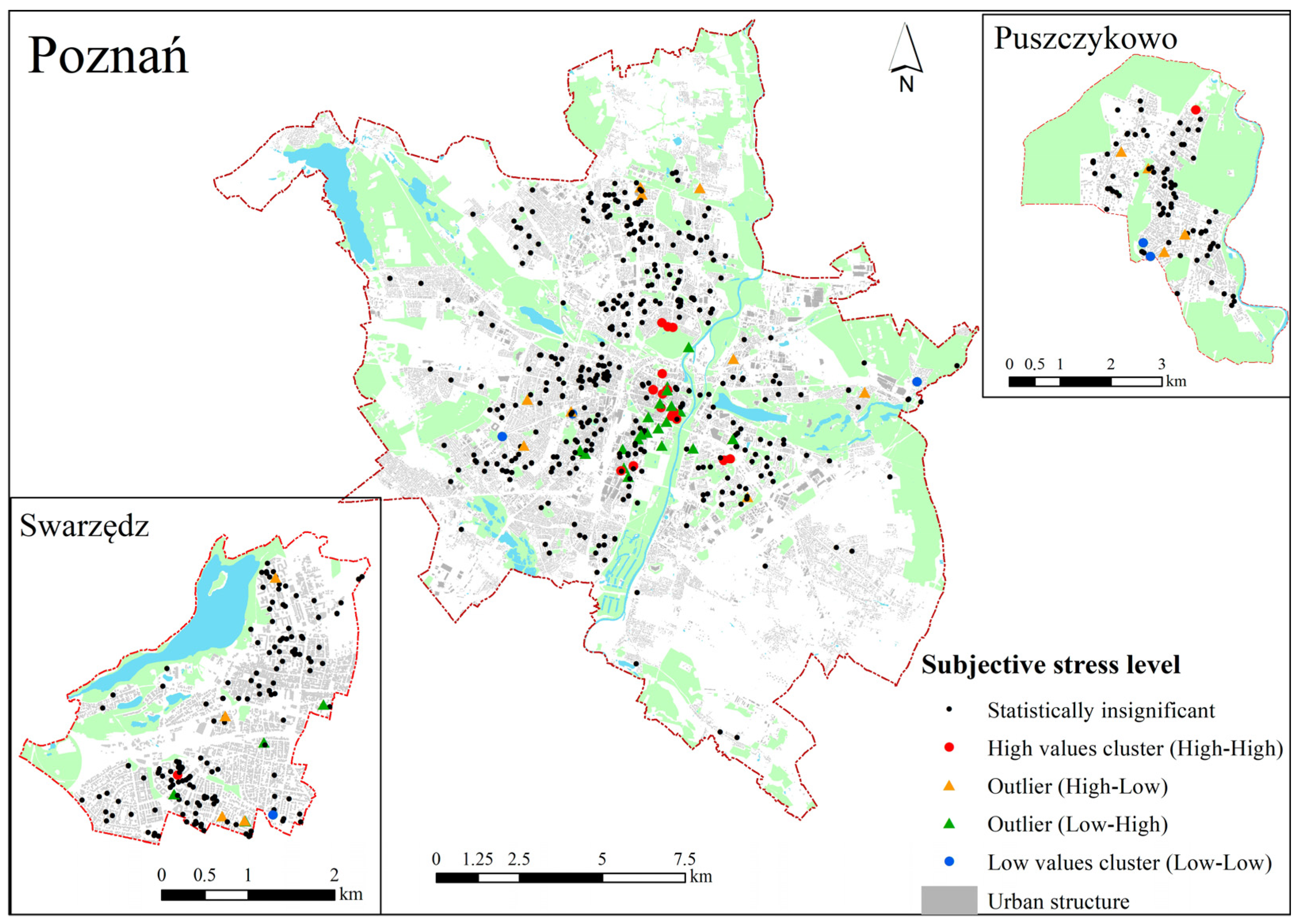

4.5. Spatial Aspects

5. Discussion

Research Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellison, C.W.; Maynard, E.S. Stress and Urban Life. In Healing For the City: Counseling in the Urban Setting; WiPF and STOCK Publisher: Eugene, OR, USA, 1992; Chapter I. [Google Scholar]

- Adli, M. Urban Stress and Mental Health. Cities, Health and Well-Being, Hong Kong, 16–17 November 2011. Available online: https://urbanage.lsecities.net/essays/urban-stress-and-mental-health (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Wang, K.; Manning, R.B., III; Bogart, K.R.; Adler, J.M.; Nario-Redmond, M.R.; Ostrove, J.M.; Lowe, S.R. Predicting depression and anxiety among adults with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rehabil. Psychol. 2022, 67, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S.; Keech, J.J.; Hamilton, K. Managing Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: Reappraisal and Mindset Approaches. Stress. Health 2020, 36, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talarowska, M.; Chodkiewicz, J.; Nawrocka, N.; Miniszewska, J.; Biliński, P. Mental Health and the SARS-CoV-2 Epidemic—Polish Research Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mierzejewska, L.; Sikorska-Podyma, K.; Szejnfeld, M.; Wdowicka, M.; Modrzewski, B.; Lechowska, E. The Role of Greenery in Stress Reduction among City Residents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I.; Whitten, M. Access to nature in a post covid-19 world: Opportunities for green infrastructure financing, distribution and equitability in urban planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misheva, V.; Hristova, A.; Palm, F.; Nacheva, I.; Hopstadius, M.; Blasko, A. Framing the “Exceptions to the Rule” in Analyses of Responses to the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Crisis and the Culture of Fear and Anxiety in Contemporary Europe; Llena, C.Z., Stier, J., Gray, B., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova, D.; Nacheva, I.; Panchelieva, T. Psychological Predictors of COVID-19-Related Anxiety in Vulnerable Groups. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1815–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Miller, J.G.; Hartman, T.K.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; McKay, R.; Stocks, T.V.A.; et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, X.; Yan, J.; Miao, H.; Guo, C. Anxiety and depression in Chinese students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 697642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.O.; Hülsdünker, T.; Carson, F. The Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on European Students’ Negative Emo-tional Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhanunni, A.; Pretorius, T.B.; Isaacs, S.A. We are Not Islands: The Role of Social Support in the Relationship between Perceived Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Psychological Distress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 4, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Nyberg, S.T.; Batty, G.D.; Fransson, E.I.; Heikkilä, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; Casini, A.; et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012, 380, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahola, A.J.; Harjutsalo, V.; Saraheimo, M.; Forsblom, C.; Groop, P.-H.; FinnDiane Study Group. Purchase of antidepressant agents by patients with type 1 diabetes is associated with increased mortality rates in women but not in men. Diabetologia 2011, 55, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magano, J.; Vidal, D.G.; Sousa, H.F.P.e.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Leite, Â. Psychological Factors Explaining Perceived Impact of COVID-19 on Travel. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1120–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Anderies, J.M.; Kinzig, A.P.; Ryan, P. Exploring resilience in social-ecological systems through comparative studies and theory development: Introduction to the special issue. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Leszcz, M.; Savage, D.; Adam, M.A.; Peladeau, N.; Romano, D.; Rose, M.; Schulman, R.B. Applying the lessons of SARS to pandemic influenza: An evidence-based approach to mitigating the stress experienced by healthcare workers. Can. J. Public Health 2008, 99, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerin, C.M.; Lind, M.J.; Brown, E.A.; Gardner, C.O.; Kendler, K.S.; Amstadter, A.B. The impact of resilience and subsequent stressful life events on MDD and GAD. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilay, R.; Moore, T.M.; Greenberg, D.M.; DiDomenico, G.E.; Brown, L.A.; White, L.K.; Gur, R.C.; Gur, R.E. Resilience, COVID19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Solmaz, F. COVID-19 burnout, COVID-19 stress and resilience: Initial psychometric properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Stud. 2022, 46, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haileamlak, A. Pandemics Will be More Frequent. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2022, 32, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Risk and Resilience in Human Development: An Introduction. Res. Hum. Dev. 2004, 1, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. Editorial Introduction: Vulnerability, Coping and Policy. IDS Bull. 1989, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, O.N. The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Dev. 1998, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, T. Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, E32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, C.; Ali, S.H.; Keil, R. On the relationships between COVID-19 and extended urbanization. Dialog-Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Huang, B. Assessment of community vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic: Hong Kong as a case study. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 113, 103007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Bai, X.; Costanza, R.; Dong, L. The effects of COVID-19 on the resilience of urban life in China. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, B.; Qian, T.; Ma, H. Assessing the vulnerability of urban public health system based on a hybrid model. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1576214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Paul, K.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Samuel, J.; Thill, J.-C.; Hossain, M.A.; Nawaz Ali, G.G.M. Pandemic vulnerability index of US cities: A hybrid knowledge-based and data-driven approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN-ISDR 2004. Living with Risk: A Global Review of Disaster Reduction Initiatives International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. Available online: http://www.unisdr.org/eng/about_isdr/bd-lwr-2004-eng.htm (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Adger, N.; Brooks, N.; Bentham, G.; Agnew, M.; Eriksen, S. New Indicators of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity; Technical Report 7; Tyndall Center for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians: A Working Document; Department of National Health and Welfare, 1974; Ottawa, ON, USA. 1981. Available online: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/pdf/perspect-eng.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- House of Commons. Health and Social Care and Science and Technology Committees. Coronavirus: Lessons Learned to Date. Sixth Report of the Health and Social Care Committee and Third Report of the Science and Technology Committee of Session 2021–22. 21 September 2021; p. 32. Available online: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/7496/documents/78687/default/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Cianciara, D.; Szmigiel, A.; Pruszyński, J. Recovery from COVID-19 crisis in public health perspective. J. Educ. Health Sport 2022, 12, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, H.; Gordijn, B. Vulnerability in light of the COVID-19 crisis. Med. Health Care Philos. 2021, 24, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirkner, J.; Christiansen, H.; Knaevelsrud, C.; Lüken, U.; Wurm, S.; Schneider, S.; Brakemeier, E.L. Mental health in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Current knowledge and implications from a European perspective. Eur. Psychol. 2021, 26, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Lo Moro, G.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Bertuccio, P.; Santi, F.; Bianchi, D.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; Aguglia, A.; et al. Gender differences in COVID-19 lockdown impact on mental health of undergraduate students. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 813130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blix, I.; Birkeland, M.S.; Thoresen, S. Worry and mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic: Vulnerability factors in the general Norwegian population. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdin, S.; Bayrak Özdin, S. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Bruckner, T.; Saxena, S.; Alqunaibet, A.; Almudarra, S.; Herbst, C.H.; Alsukait, R.; El-Saharty, S.; Algwaizini, A. COVID-19 and Mental Health in Vulnerable Populations: A Narrative Review; Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35847 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Jankowski, P.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Młodkowski, M.; Zwoliński, Z. Geo-questionnaire: A method and tool for public preference elicitation in land use planning. Trans. GIS 2016, 20, 903–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąkowska, E.; Kaczmarek, T.; Mikuła, Ł. Wykorzystanie geoankiety jako narzędzia konsultacji społecznych w procesie planowania przestrzennego w aglomeracji poznańskiej. (The use of geo-questionnaire as a public consultation tool in the process or urban planning in Poznań Agglomeration). Rocz. Geomatyki 2017, 15, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, P.; Kaczmarek, T.; Zwoliński, Z.; Bąkowska-Waldmann, E.; Brudka, C.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Młodkowski, M. Zastosowanie aplikacji geoankiety i geodyskusji w partycypacyjnym planowaniu przestrzennym: Dobre praktyki. (Application of Geosurvey and Geo-Discussion in Participatory Spatial Planning); Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, W.J. Practical Nonparametric Statistics, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jaehn, P.; Fügemann, H.; Gödde, K.; Holmberg, C. Using Decision Tree Analysis to Identify Population Groups at Risk of Subjective Unmet Need for Assistance with Activities of Daily Living. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatasubramaniam, A.; Wolfson, J.; Mitchell, N.R.; Barnes, T.L.; JaKa, M.M.; French, S.A. Decision Trees in Epidemiological Research. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2017, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenova, I.; Vladimirova, R.; Stoyanova, V. Influence of Socio-Demographic Factors on Perceived Stress in Outpatients with Depression and Anxiety in Remission During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Medica Bulg. 2022, 49, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieh, C.; Budimir, S.; Probst, T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 136, 110186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumra, E.; Patange, A. Ethnic, Socioeconomic, and Demographic Determinants of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Fear of COVID-19 among Teenagers in California, United States: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Front. Educ. 2025, 9, 1496137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeogu, O.J.; Mimmack, K.J.; Gagliardi, G.; Burling, J.; Gatchel, J.R.; Quiroz, Y.T.; Donovan, N.J.; Amariglio, R.E.; Sperling, R.A.; A Marshall, G.; et al. Impact of Stress, Loneliness and Sociodemographic Factors on Psychological Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E.E.; Presskreischer, R.; Anderson, K.E.; Han, H.; Barry, C.L. Psychological Distress and COVID-19–Related Stressors Reported in a Longitudinal Cohort of US Adults in April and July 2020. JAMA 2020, 324, 2555–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfin, D.R.; Djokovic, L.; Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A. Acute stress, worry, and impairment in health care and non-health care essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T.; Aughterson, H.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. “Stressed, Uncomfortable, Vulnerable, Neglected”: A Qualitative Study of the Psychological and Social Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Frontline Keyworkers. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlas, L.Y.; Farmer, C.; Shaw, J.S.; Gibbons, A.; Guinee, E.P.; Lossio-Ventura, J.A.; Ballard, E.D.; Ernst, M.; Japee, S.; Pereira, F.; et al. Dynamic effects of psychiatric vulnerability, loneliness and isolation on distress during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Ment. Health 2025, 3, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoi, P.T. Ho Chi Minh City- the front line against COVID-19 in Vietnam. City Soc. 2020, 32, 10–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra-Ortega, A.; González, A.; Fernández-Batalla, M.; Macario, E.; Diego, B.; Jimenez, M.; Santamaría-García, J. Community Vulnerability: Measuring the Health Situation of a Population After COVID-19 Through Electronic Health Record Indicators. Healthcare 2025, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, R.K. Smart Cities After COVID-19: Ten Narratives. disP—Plan. Rev. 2020, 56, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orford, S.; Fan, Y.; Hubbard, P. Urban public health emergencies and the COVID-19 pandemic. Part 1: Social and spatial inequalities in the COVID-city. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1329–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Groups Vulnerable to Pandemic Stress |

|---|---|

| Bakalova et al., 2023 [9] |

|

| Shevlin et al., 2020 [10] Gualano et al., 2020 [42] |

|

| Amerio et al., 2022 [43] |

|

| Blix et al., 2021 [44] |

|

| Özdin et al., 2020 [45] |

|

| Wang et al., 2022 [3] |

|

| Rahman et al., 2023 [34] |

|

| Das et al., 2021 [46] |

|

| Metrics | Category | No. of Respondents | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 | 347 | 29.0 |

| 26–35 | 309 | 25.8 | |

| 36–60 | 496 | 41.4 | |

| 61–70 | 38 | 3.1 | |

| 70+ | 8 | 0.7 | |

| Sex/gender | Woman | 828 | 69.1 |

| Man | 347 | 29.0 | |

| Other gender | 23 | 1.9 | |

| Education | Vocational | 56 | 4.7 |

| Elementary | 32 | 2.7 | |

| Secondary | 388 | 32.4 | |

| Higher | 722 | 60.2 | |

| Occupational activity | School/university student | 264 | 22.0 |

| Unemployed | 54 | 4.5 | |

| Pensioner | 48 | 4.0 | |

| Public sector employee | 336 | 28.1 | |

| Private sector employee | 379 | 31.6 | |

| Entrepreneur | 117 | 9.8 | |

| Profession practised | Medical personnel (outpatient clinics, hospital), paramedic | 55 | 4.6 |

| Nursery/preschool staff | 32 | 2.7 | |

| Catering staff | 38 | 3.2 | |

| Tourism/culture and entertainment staff | 33 | 2.8 | |

| Grocery/pharmacy salesperson | 42 | 3.5 | |

| Professional driver/taxi driver/public transport driver | 19 | 1.6 | |

| Teacher/academic teacher | 122 | 10.2 | |

| Other occupation | 856 | 71.4 | |

| Number of persons in household | 1 | 203 | 16.9 |

| 2 | 315 | 26.3 | |

| 3 | 274 | 22.9 | |

| 4 | 286 | 23.9 | |

| 5 | 88 | 7.3 | |

| ≥6 | 32 | 2.7 | |

| Number of persons in household aged 60+ | 0 | 1023 | 85.4 |

| 1 | 110 | 9.2 | |

| 2 | 61 | 5.1 | |

| 3 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| Number of children in household | 0 | 674 | 56.3 |

| 1 | 211 | 17.6 | |

| 2 | 232 | 19.4 | |

| 3 | 59 | 4.9 | |

| 4 | 18 | 1.5 | |

| ≥5 | 4 | 0.3 | |

| Nursery-age children | 0 | 1119 | 93.4 |

| 1 | 73 | 6.1 | |

| 2 | 5 | 0.4 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Preschool-age children | 0 | 1038 | 86.6 |

| 1 | 132 | 11.0 | |

| 2 | 24 | 2.0 | |

| 3 | 4 | 0.4 | |

| Early-school-age children (classes 1–3) | 0 | 1043 | 87.1 |

| 1 | 141 | 11.7 | |

| 2 | 13 | 1.1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| School-age children (classes 4–8) | 0 | 999 | 83.4 |

| 1 | 172 | 14.3 | |

| 2 | 25 | 2.1 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| 4 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Secondary-school-age children | 0 | 994 | 83.0 |

| 1 | 149 | 12.4 | |

| 2 | 46 | 3.8 | |

| 3 | 7 | 0.6 | |

| 4 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| 5 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Cities | Mean | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5.51 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 2.67 | 0 | 10 |

| Metrics | Category | Mean | Kruskal–Wallis | p-Value | Effect Strength (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 | 5.24 | 8.99 | 0.06 | Statistically insignificant |

| 26–35 | 5.58 | ||||

| 36–60 | 5.57 | ||||

| 61–70 | 6.61 | ||||

| 70+ | 5.63 | ||||

| Sex/gender | Man | 4.89 | 26.92 | <0.001 | 0.02 (small effect) |

| Woman | 5.74 | ||||

| Other gender | 6.57 | ||||

| Education | Elementary | 5.66 | 1.937 | 0.585 | Statistically insignificant |

| Vocational | 5.96 | ||||

| Secondary | 5.41 | ||||

| Higher | 5.52 | ||||

| Occupational activity | Pensioner | 6.23 | 12.339 | 0.03 | 0.006 (small effect) |

| Unemployed | 6.13 | ||||

| Private sector employee | 5.49 | ||||

| Public sector employee | 5.68 | ||||

| Entrepreneur | 5.30 | ||||

| School/university student | 5.16 | ||||

| Profession practised | Medical personnel (outpatient clinic, hospital) | 5.87 | 14.212 | 0.05 | 0.006 (small effect) |

| Nursery/preschool staff | 6.39 | ||||

| Catering staff | 5.92 | ||||

| Tourism/culture and entertainment staff | 6.61 | ||||

| Grocery/pharmacy salesperson | 5.36 | ||||

| Professional driver/taxi driver/public transport driver | 6.11 | ||||

| Teacher/academic teacher | 5.59 | ||||

| Other occupation | 5.38 | ||||

| Number of persons in household | 1 | 5.49 | 2.676 | 0.75 | Statistically insignificant |

| 2 | 5.53 | ||||

| 3 | 5.49 | ||||

| 4 | 5.43 | ||||

| 5 | 5.59 | ||||

| ≥6 | 6.19 | ||||

| Number of persons in household aged 60+ | 0 | 5.44 | 5.45 | 0.14 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.77 | ||||

| 2 | 6.05 | ||||

| 3 | 7.25 | ||||

| Number of children in household | 0 | 5.51 | 3.84 | 0.58 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.60 | ||||

| 2 | 5.47 | ||||

| 3 | 5.07 | ||||

| 4 | 6.33 | ||||

| ≥5 | 6.50 | ||||

| Nursery-age children | 0 | 5.49 | 1.75 | 0.42 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.78 | ||||

| ≥2 | 6.83 | ||||

| Preschool-age children | 0 | 5.52 | 3.39 | 0.33 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.53 | ||||

| 2 | 5.17 | ||||

| 3 | 3.50 | ||||

| Early-school-age children (classes 1–3) | 0 | 5.50 | 2.35 | 0.31 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.50 | ||||

| ≥2 | 6.43 | ||||

| School-age children (classes 4–8) | 0 | 5.56 | 2.88 | 0.24 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.27 | ||||

| ≥2 | 5.04 | ||||

| Secondary-school-age children | 0 | 5.48 | 5.94 | 0.11 | Statistically insignificant |

| 1 | 5.55 | ||||

| 2 | 6.30 | ||||

| ≥3 | 4.33 |

| Predictors | Number of Nodes | Chi-Square (χ2 Test) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profession practiced | 3 | 84.75 | 0.000000 |

| Sex/gender | 2 | 40.60 | 0.000053 |

| Education | 3 | 51.56 | 0.001056 |

| Occupational activity | 3 | 46.01 | 0.025690 |

| Number of people aged 60+ | 2 | 16.04 | 0.787663 |

| Age | 3 | 31.03 | 0.876818 |

| Number of persons in household | 3 | 29.25 | 1.000000 |

| Number of children in household | 3 | 17.35 | 1.000000 |

| Predictors | B (Estimate) | Std. Error | Wald Statistic | p-Value | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.077 | 0.293 | 0.068 | 0.794 | ||

| Household size | 0.053 | 0.073 | 0.514 | 0.473 | 1.054 | 0.913–1.217 |

| Number of persons 60+ | 0.021 | 0.134 | 0.026 | 0.873 | 1.022 | 0.786–1.327 |

| Number of children in household | −0.101 | 0.093 | 1.180 | 0.277 | 0.904 | 0.753–1.085 |

| Age (Ref: 70+) | (0.766) a | |||||

| 18–25 | −0.238 | 0.273 | 0.761 | 0.383 | 0.808 | 0.147–4.450 |

| 26–35 | −0.023 | 0.234 | 0.010 | 0.920 | 1.002 | 0.189–5.319 |

| 36–60 | −0.073 | 0.225 | 0.107 | 0.744 | 0.953 | 0.182–4.986 |

| 61–70 | 0.360 | 0.350 | 1.059 | 0.303 | 1.471 | 0.281–7.686 |

| Sex/Gender (Ref: other gender) | (0.0003) a | |||||

| Man | −0.415 | 0.170 | 5.934 | 0.015 | 0.507 | 0.207–1.242 |

| Woman | 0.150 | 0.159 | 0.892 | 0.345 | 0.892 | 0.373–2.133 |

| Education (Ref: higher) | (0.087) a | |||||

| Vocational | 0.233 | 0.237 | 0.966 | 0.326 | 1.778 | 0.974–2.247 |

| Primary | 0.159 | 0.292 | 0.297 | 0.585 | 1.652 | 0.765–3.566 |

| Secondary | −0.049 | 0.145 | 0.115 | 0.735 | 1.341 | 1.000–1.798 |

| Profession practised (Ref: catering staff) | (0.137) a | |||||

| Medical personnel (outpatient clinic, hospital) | −0.321 | 0.269 | 1.418 | 0.234 | 0.781 | 0.327–1.867 |

| Grocery/pharmacy salesperson | −0.347 | 0.306 | 1.289 | 0.256 | 0.761 | 0.302–1.916 |

| Professional driver | −0.101 | 0.453 | 0.050 | 0.822 | 0.973 | 0.293–3.230 |

| Teacher/Academic teacher | −0.290 | 0.212 | 1.865 | 0.172 | 0.805 | 0.363–1.785 |

| Nursery/Preschool worker | 0.448 | 0.337 | 1.769 | 0.184 | 1.686 | 0.625–4.545 |

| Other occupation | −0.123 | 0.136 | 0.823 | 0.364 | 0.952 | 0.479–1.889 |

| Tourism, culture and entertainment staff | 0.810 | 0.341 | 5.630 | 0.018 | 2.422 | 0.907–6.467 |

| Occupational activity (Ref: unemployed) | (0.685) a | |||||

| Pensioner | −0.208 | 0.328 | 0.401 | 0.527 | 0.639 | 0.256–1.597 |

| Private sector employee | 0.071 | 0.134 | 0.283 | 0.595 | 0.845 | 0.460–1.554 |

| School/university student | −0.107 | 0.204 | 0.275 | 0.600 | 0.707 | 0.354–1.415 |

| Entrepreneur | −0.139 | 0.194 | 0.515 | 0.473 | 0.685 | 0.341–1.375 |

| Public sector employee | 0.144 | 0.145 | 0.979 | 0.322 | 0.908 | 0.487–1.695 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mierzejewska, L.; Zhukouskaya, N. Identifying Pandemic Stress-Vulnerable Social Groups in Selected Polish Cities: A Geospatial Approach to Building Resilience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125580

Mierzejewska L, Zhukouskaya N. Identifying Pandemic Stress-Vulnerable Social Groups in Selected Polish Cities: A Geospatial Approach to Building Resilience. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125580

Chicago/Turabian StyleMierzejewska, Lidia, and Natallia Zhukouskaya. 2025. "Identifying Pandemic Stress-Vulnerable Social Groups in Selected Polish Cities: A Geospatial Approach to Building Resilience" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125580

APA StyleMierzejewska, L., & Zhukouskaya, N. (2025). Identifying Pandemic Stress-Vulnerable Social Groups in Selected Polish Cities: A Geospatial Approach to Building Resilience. Sustainability, 17(12), 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125580