1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of global trade and consumer demand places significant pressure on supply chain operations. Between 1995 and 2019, global energy consumption surged from 8588.9 to 13,147.3 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe) [

1], reflecting the growing demands placed on industries, including warehousing. This rise in energy usage is driven by the need to meet consumer expectations for faster production times and the continuous expansion of manufacturing capabilities worldwide [

2]. As industries strive to optimize their operations to remain competitive [

3], a series of environmental, social, and economic impacts due to increased energy consumption cannot be ignored.

Climate change is one of the environmental impacts that has gained widespread acknowledgment; this includes a rise in the earth’s temperature due to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [

4], extreme weather events, sea-level rise, disrupted ecosystems, and food and water scarcity. Since these effects are becoming more apparent, there is a growing recognition that unsustainable practices worsen these issues [

5]. Therefore, the pressing challenge now lies in balancing the demands of production with sustainable practices that mitigate the negative impact on the planet. This scenario underscores the urgent need for sustainable transformation of all supply chain sectors [

6].

According to Fichtinger et al. [

7], a considerable 13% of emissions in the supply chain come from logistics buildings, which include sorting and distribution centers and warehouses. Consequently, it is important to highlight and understand how warehousing operations can be optimized and modified to address and mitigate a supply chain’s environmental impact. In response, sustainable warehousing practices have gained increasing attention as individuals, businesses, policymakers, and researchers seek to balance economic efficiency with ecological responsibility and social well-being [

8].

Despite the increasing interest in sustainable warehousing, there remains a lack of a unified theoretical framework that defines and guides its implementation. While existing studies have explored sustainability in logistics and supply chains, research on sustainable warehousing as a distinct domain requires further investigation and a more comprehensive approach [

9]. Additionally, no single paper comprehensively defines the key factors driving sustainability in warehousing, such as cost savings, regulations, and corporate responsibility, nor systematically addresses the barriers, including high initial costs, lack of awareness, and operational challenges. Furthermore, there is a lack of practical guidance on implementing sustainability and a framework that effectively supports this transition. Addressing these gaps is crucial for developing a holistic approach to sustainability in warehousing that aligns with broader environmental, social, and economic objectives.

This study aims to address the existing gap as outlined above by developing a comprehensive framework for sustainable warehousing by synthesizing insights from existing literature. The research aims at the following research objectives (RO):

RO1: Overview of the current state of the art in sustainable warehousing.

RO2: Creation of a framework for integrating sustainability into warehousing operations.

To achieve these objectives, this contribution examines the primary drivers, challenges, and best practices of sustainable warehousing and proposes a structured approach for its implementation. The findings contribute to both academic research and practical applications, offering valuable recommendations for industry stakeholders and policymakers. By providing an in-depth analysis of sustainability in warehousing, this study emphasizes the necessity of transitioning from conventional practices to more sustainable models. The research highlights the importance of incorporating ecological, economic, and social dimensions to foster a resilient and efficient warehousing sector that supports sustainable supply chains. Ultimately, this study seeks to advance the discourse on sustainable warehousing and make a meaningful contribution to the broader field of sustainable logistics and supply chain management.

This study is structured into six main sections to provide a comprehensive understanding of sustainability in warehousing. It begins with

Section 1, which establishes the research context, objectives, and significance.

Section 2 presents the theoretical background by examining sustainability from environmental, social, and economic perspectives and by exploring key logistics components, highlighting both strategic and operational dimensions. This section also differentiates the present study from existing literature reviews.

Section 3 outlines the methodological approach and describes the research design.

Section 4 presents the results of the literature review, identifying key drivers, barriers, and emerging practices in sustainable warehousing.

Section 5 offers a critical discussion of the findings and introduces a framework to guide sustainable warehousing practices. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the study by summarizing key insights, discussing its contributions, and suggesting directions for future research.

3. Methodological Approach

This literature review follows comprehensive guidelines from well-established sources, outlined by Kitchenham and Brereton [

44] and Kitchenham et al. [

45], as well as the guidelines provided by Nightingale [

46], to ensure a systematic and reproducible approach. Kitchenham’s framework provides a structured process for identifying, selecting, and analyzing relevant research, reducing bias, and enhancing transparency. Originally developed for software engineering research, Kitchenham’s method has been widely adopted across various disciplines, including sustainability studies, due to its robustness and reliability. By following this well-established method, we ensure that our results can be reproduced by other researchers using the same steps. This aligns with the principles of evidence-based research and allows for a rigorous synthesis of the existing literature on sustainability in warehousing. Furthermore, Kitchenham’s structured approach ensures comprehensive coverage of the relevant literature, facilitating an objective evaluation of drivers, barriers, and practices in sustainable warehousing.

The method for this literature review follows a three-step process, as outlined in

Figure 2: Data Collection, Data Selection, and Data Analysis. The process begins with a comprehensive search across multiple scholarly databases, using specific keywords to capture a broad yet relevant set of studies on sustainable warehousing. Inclusion criteria are applied to ensure that the selected articles are diverse but directly related to the topic. Once the data is collected, the studies are screened and evaluated based on predefined content criteria to retain only the most relevant and high-quality research. In the final step, the selected studies are categorized and analyzed thematically to identify key trends, drivers, barriers, and practices in sustainable warehousing. This analysis serves as the foundation for developing a comprehensive framework that aligns current practices with sustainability goals, providing actionable insights for stakeholders in the warehousing industry.

3.1. Data Collection

The method used to collect data involves a general review conducted through Google Scholar, which initially yields hundreds of thousands of articles. These include peer-reviewed journal articles, research papers, and relevant books. However, not all the articles gathered are immediately relevant; some have hundreds of citations, while others lack citations altogether. Moreover, the nature of the articles varies, with some being literature reviews and others based on case studies, making it challenging to determine their suitability for inclusion in this contribution. To refine the search and adopt a more systematic approach, the use of “Publish or Perish” software becomes essential. This tool facilitates initial searches across various databases based on specific keywords, resulting in a more focused collection of relevant articles, studies, and papers. The software allows for targeted searches, emphasizing articles with higher relevance and impact within the field of sustainable warehousing, thereby ensuring the quality and pertinence of the selected literature. Subsequently, the inclusion criteria are defined to ensure that only articles meeting these specified criteria are selected, as shown in

Table 2 below.

The data collection process involves gathering a wide range of academic publications on sustainability in both supply chain management and warehousing, utilizing reputable academic databases and feasible combinations of the listed keywords. Accepted source types include peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, and research articles. Additionally, only articles written in English are considered. The initial search across various scholarly databases yields a total of 2429 articles. After removing duplicate entries, the number is reduced to 1685 unique articles.

To ensure the relevance and quality of the selected literature, specific exclusion criteria are applied during the screening process. These criteria help filter out studies that do not align with the research focus or methodological standards.

Table 3 below outlines the exclusion criteria used in the collection process.

A scatter chart is initially created following the guidelines outlined by Mohamed Shafril et al. [

47] to visualize the frequency of publications over time, as illustrated in

Figure 3. This visualization provides a clear picture of publication trends, helping to determine the appropriate cutoff year for inclusion in the study. It provides a clear picture of publication trends, which informs the next steps of the review process. Publications from 2024 were considered only until July of that year, thus the decline.

Upon revisiting the scatter chart above, it becomes apparent that there are very few relevant publications prior to 2008. This indicates that the topic had limited significance in earlier years. Based on this observation, the publication period is restricted to articles published from 2008 to July 2024, reducing the dataset to 1647 publications.

Subsequently, books are excluded from the dataset to ensure compliance with the exclusion criteria outlined above, leading to a total of 1606 publications moving forward to the next set of exclusion criteria. This further refines the collection process and ensures a robust and up-to-date dataset for analysis.

Additional criteria are applied to further refine the selection, excluding articles with fewer than ten citations. This reduces the number of publications to 1316. This step ensures that the selected literature has been validated by the academic community, as higher citation counts indicate significant contributions to the field. This enhances the reliability and quality of the literature review by focusing on well-regarded studies that have influenced subsequent research and practice.

Finally, the last exclusion criteria are applied to exclude any non-reputable publishers. Using Beall’s list, any articles from questionable, predatory, or borderline publishers are removed, resulting in 1235 articles being considered for the next step. The detailed process is summarized in

Table 4.

At the end of the data collection process, a total of 1235 publications met both the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the next phase, an in-depth review is conducted, focusing on content criteria to further refine the selection.

3.2. Data Selection

The selection process begins by evaluating all potentially relevant publications that align with the established inclusion criteria. Following this initial screening, the publications are further assessed using the content criteria detailed in

Table 5, which are applied to finalize the selection of sources for the study.

The content criteria, as outlined above, prioritized original research contributions while excluding literature reviews to concentrate on primary data and insights. Additionally, the articles included had to be directly relevant to sustainability in warehousing or supply chains, focusing on practices, motivations, or challenges related to these topics. Moreover, the primary emphasis of the publications must be on sustainability rather than on topics related to AI. This detailed approach ensured that only the most relevant and impactful studies were incorporated into the final analysis.

Table 6 details the five stages that articles could progress through during the selection process based on the content criteria. Each document may undergo the four-stage review process, advancing only if it successfully passes the previous stage. The fifth stage is a validation step that identifies and includes significant papers cited in the literature but not initially retrieved through the chosen database. This systematic approach ensures that only the most relevant and high-quality publications are included in the final analysis, maintaining the thoroughness and focus of the research.

Throughout the data collection process, a total of 1235 publications in Stage I are reviewed based on the inclusion criteria. Out of these, 395 publications advance to Stage II. At this stage, 29 publications are excluded as they are literature reviews related to warehousing and supply chains. Subsequently, Stages III and IV are conducted, with 42 publications ultimately making it to Stage IV as their full text meets the content criteria necessary for the selection process.

The selection process extends beyond the fourth stage, incorporating a validation step to ensure that the chosen databases and search terms effectively capture all relevant research in this structured literature review. This step, commonly employed in systematic reviews, helps to identify and include significant papers that may have been cited in the literature but were not initially retrieved through the selected database [

48]. As a result, two additional papers related to climate issues and governmental regulations—topics not covered by the initial keywords—are included to enhance the value of this contribution. This brings the total number of publications in the literature review to 44.

Table 7 below provides a breakdown of the number of contributions that progress through each stage.

3.3. Data Analysis

In the data analysis section, following the data collection and selection processes, the selected papers are initially categorized after thorough reading. To streamline the review process and enhance clarity, the collected literature is organized into five main thematic groups:

- Group 1.

Strategic Frameworks for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: This group focuses on foundational frameworks, models, and strategies designed to implement sustainability across the supply chain, including theoretical and strategic perspectives.

- Group 2.

Operational Approaches to Sustainable Logistics: This group zooms into the operational level. It explores sustainability practices, low-carbon solutions, and the decarbonization of logistics operations.

- Group 3.

Challenges, Barriers, Motivations, and Drivers for Adopting Sustainability: This category addresses the obstacles, incentives, and factors influencing the adoption of sustainable practices in supply chains and warehouses.

- Group 4.

Practices and Trends Towards Sustainability: This section examines emerging practices and trends that support sustainability efforts.

- Group 5.

Climate Issues and Governmental Regulations: This category includes the literature on climate-related issues and relevant governmental regulations affecting sustainability practices.

Categorizing the articles into these specific areas allows for a more efficient review, helping to organize the literature more easily and providing a clear vision of how the review chapter is structured. This facilitates the identification of which papers are most relevant to each section of the literature review. It is important to note that some articles span multiple categories and, thus, are relevant to more than one group, as shown in

Table 8 below. This approach also aids in focusing on key studies, ensuring that the most significant contributions to the research topic are highlighted.

4. Results

Given the growing awareness of environmental impact and the pressure to adopt more sustainable practices, the role of sustainability in warehousing and logistics operations has gained significant attention among individuals, businesses, and policymakers.

This chapter provides an in-depth review of the existing literature on sustainability in warehousing, offering critical background for understanding the current landscape. It begins with a discussion on the conceptualization of sustainability within supply chains and warehousing. The chapter then addresses the challenges and barriers to sustainable warehousing, followed by an exploration of the motivations and drives that encourage sustainability initiatives in this sector. Recognizing these factors is considered essential, as identifying them at an early stage can significantly contribute to the successful implementation of SSCM [

3]. The chapter concludes by examining current sustainability practices and trends, illustrating how organizations integrate sustainable principles into their operations. Collectively, these elements serve as the foundation for developing an intermediate framework for sustainability in warehousing in the next chapter, integrating insights from literature to inform future research and practice.

4.1. Conceptualization of Sustainability in Supply Chain and Warehousing

A sustainable supply chain is a network of businesses and processes designed to minimize negative environmental impacts, ensure social responsibility, and promote economic viability throughout the entire lifecycle of a product, from raw material sourcing to final delivery and disposal [

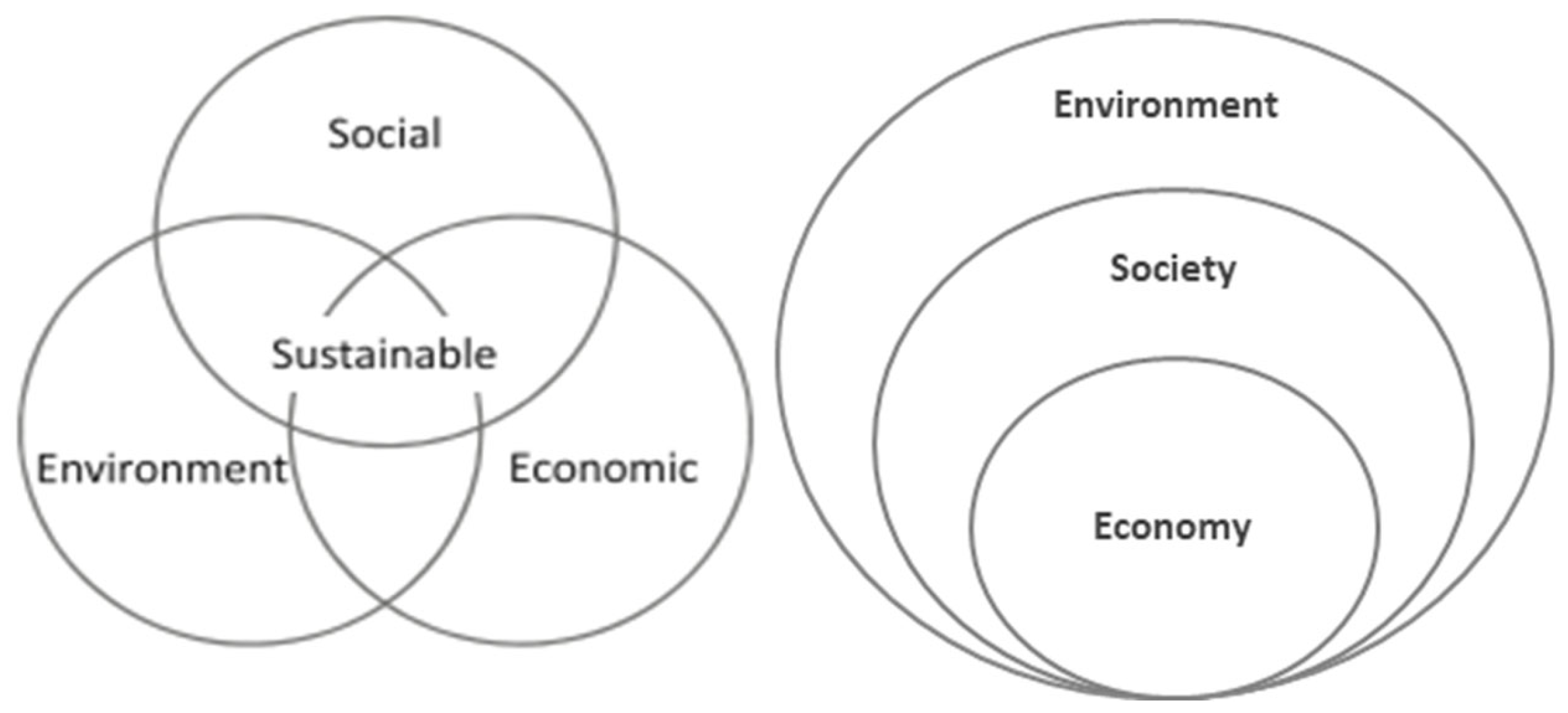

49]. It focuses on balancing environmental, social, and economic factors, as shown in

Figure 4, to create long-term value while reducing waste, conserving resources, and supporting ethical practices [

50]. This approach extends the traditional economic dimension of supply chains to encompass the TBL framework, as explained in

Section 2.1 of this contribution.

In the context of SSCM, the focus shifts to managing the supply chain while considering environmental, social, and economic aspects. Tan describes SSCM as the “management of raw materials and services from suppliers to manufacturer/service provider to the customer and back, with the improvement of the social and environmental impacts explicitly considered” [

51]. According to Grzybowska and Kovács, SSCM is “the management of material, information, and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while integrating goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development, i.e., economic, environmental and social, which are derived from customer and stakeholder requirements” [

50].

A related term often confused with SSCM is green supply chain management (GSCM). However, GSCM focuses exclusively on the environmental performance of supply chains [

52], whereas SSCM encompasses the full spectrum of sustainability, including environmental, social, and economic dimensions. For example, Sundarakani et al. describe GSCM as “the integration of environmental thinking into supply chain management, including product design, supplier selection and material sourcing, manufacturing processes, product packaging, delivery of the product to the consumers, and end-of-life management of the product after its use” [

53].

Managers are increasingly motivated to implement greener supply chain practices due to a variety of strategic benefits, including a stronger corporate image, improved operational efficiency, leadership in innovation, cost reductions, and enhanced product value [

54]. These drivers, along with other strategic motivations, will be explored in detail in the following sections. In the context of SSC, sustainability can be incorporated at multiple stages of the supply chain, including product design, purchasing, manufacturing processes, packaging, warehousing, transportation, recycling, reusing, and disposal [

52]. Among these stages, warehousing plays a critical role in advancing sustainability efforts.

Section 2.2 of this contribution highlights that warehouses significantly contribute to greenhouse gas emissions within supply chains [

21]. Warehousing and goods handling activities, such as the handling of hazardous substances and the movement of vehicles between warehouses, are responsible for up to three percent of global energy-related CO2 emissions [

5]. The rise in academic interest in green and sustainable warehousing is a response to the increasing recognition of the environmental impacts of these facilities [

55].

Examining sustainability in logistics and warehousing provides valuable insights, especially when considering its impact on various operational aspects. Several authors have referred to sustainable warehouses as ‘green’ warehouses because they prioritize environmental responsibility in their operations. However, some have argued that the distinctions between ‘green’ warehouses and sustainable warehouses are becoming increasingly blurred [

56]. Ali and Kaur, as well as Tan et al., have noted that much of the existing literature has focused on environmental and economic sustainability in warehouses. However, the area of social sustainability in warehousing warrants further investigation [

2,

57].

Wahab et al. defines green warehousing as the integration of environmentally friendly practices within warehousing operations, a key component of green logistics [

58]. In their research, they emphasize the importance of minimizing ecological impacts by enhancing warehousing functions and infrastructure, aiming to reduce carbon footprints and environmental degradation while simultaneously addressing economic pressures related to cost reduction. Additionally, they explore the antecedents of green warehouse practices, which will be covered later in this contribution.

According to Żuchowski, a sustainable warehouse is defined as a “set of organizational and technological solutions whose aim is to efficiently execute warehouse processes, with the highest social standards met, with the lowest possible environmental impact and taking financial effectiveness into account” [

59]. Similarly, Tan et al. and Ishizaka et al. describe sustainable warehousing as involving the integration, balance, and management of economic, environmental, and social aspects within warehouse operations [

57,

60]. This approach focuses on effectively managing the inputs and outputs across these dimensions to promote sustainability in warehouse management practices.

Additional, more comprehensive definitions of sustainable warehousing that consider the social aspect have been suggested by Malinowska et al., as it is a strategy aimed at optimizing the efficiency and effectiveness of warehouse operations while ensuring that the firm’s economic goals are achieved without causing any harm to the environment and society [

56]. Integrating social sustainability offers significant benefits to organizations, including an enhanced business image and improved long-term performance [

2], as it addresses critical issues such as labor rights, gender inequality, and the promotion of ethical business practices. By tackling these problems, sustainable warehousing contributes not only to a healthier work environment but also to the broader society.

In reviewing the literature on sustainability in supply chain management and warehousing, it is evident that the integration of sustainable practices is no longer a mere option but a necessity for both modern and established businesses. The evolving understanding of sustainability now encompasses not just environmental considerations but also economic and social dimensions, forming a holistic approach that seeks to balance profitability with ethical responsibility and environmental stewardship.

The literature reveals a growing emphasis on the role of sustainable warehousing as a critical component of a sustainable supply chain. Sustainable warehouses go beyond traditional functions of storage and distribution, incorporating energy-efficient technologies, waste reduction practices, and renewable energy sources. Moreover, economic sustainability is achieved through cost-effective operations and long-term financial viability that minimize resource consumption, while social sustainability emphasizes the importance of fair labor practices, enhancing labor conditions, community engagement, and overall well-being.

Despite the progress, the literature also highlights gaps in understanding, particularly in the area of social sustainability in warehousing. Environmental and economic aspects, however, have been extensively studied.

4.2. Challenges and Barriers to Sustainable Warehouses

Implementing sustainable warehousing practices presents numerous challenges that organizations must overcome. Narimissa et al. identified sustainable supply chain barriers as factors affecting negatively and preventing the adoption of green initiatives [

3]. These barriers can hinder progress and reduce the effectiveness of sustainability initiatives. Understanding these obstacles is crucial for developing strategies to address and mitigate them, ensuring successful implementation and long-term sustainability in warehousing operations. This section explores the key barriers to sustainable warehousing, providing insights into the complexities and difficulties faced by organizations in this endeavor.

Public and societal expectations—such as pressure from NGOs, local communities, or media—frequently target warehousing facilities as visible symbols of a company’s environmental and social responsibility. Issues like working conditions, neighborhood disruption, and emissions transparency are common triggers for reputational risk. These warehousing-specific dynamics highlight why sustainability challenges in warehouses deserve focused analysis distinct from general supply chain management, and they reflect the paper’s core contribution.

An analysis of the existing literature highlights the obstacles to incorporating sustainable practices in warehouses and supply chains. According to Goh it is reasonable to assume that the challenges facing sustainable supply chains are likely also applicable to sustainable warehousing, given that warehousing is an integral component of supply chains [

61].

These barriers are divided into internal and external categories. External barriers refer to factors beyond the organization’s control. As mentioned earlier, suppliers are an essential component of a supply chain. Therefore, when implementing a sustainable supply chain, it is crucial to closely monitor and engage with suppliers [

62]. Poor supplier commitment to sustainability stands as a critical external barrier that can significantly hinder the overall success of sustainable warehousing efforts, as highlighted by several authors [

61,

63]. Suppliers may resist adopting environmentally friendly processes due to cost concerns, lack of awareness and knowledge, or inadequate infrastructure. This resistance disrupts the flow of sustainable materials and practices, harming the overall sustainability efforts of warehousing operations.

While many studies address these barriers from a broad supply chain perspective, their impact on warehousing operations is often more direct and measurable. For example, supplier-related sustainability issues in warehousing are not limited to raw material sourcing. They affect inbound packaging formats, coordination of deliveries, and waste handling procedures at the warehouse level. Poor sustainability standards in packaging or logistics can lead to increased labor hours, higher energy consumption, and excess waste generation, posing practical challenges for warehouse managers seeking to implement sustainable practices.

Suppliers are an integral part of the supply chain, but customers also play a crucial role in the success of sustainable warehousing efforts. Poor commitment from customers to sustainability [

62], coupled with insufficient awareness and understanding of the importance of sustainable practices [

64], can serve as a significant external barrier. When customers do not prioritize or support sustainable practices but instead prioritize cost and time over environmental sustainability [

65] and apply pressure to keep prices low [

66], it becomes increasingly difficult for organizations to justify and invest in green initiatives. Customer expectations for low prices and rapid delivery often translate into increased energy consumption at the warehouse level due to urgent order picking, inefficient batch processing, and underutilized transport loads. These operational inefficiencies conflict directly with sustainability objectives such as energy efficiency and emissions reduction. The mismatch between customer expectations and sustainable warehousing goals creates a substantial challenge for businesses attempting to maintain environmentally responsible operations.

Moreover, uncertain and unclear regulations and legislation can sometimes work against sustainable warehousing efforts [

62]. When rules are ambiguous or inconsistent, organizations struggle to understand and meet environmental standards [

67]. This uncertainty can delay the adoption of sustainable practices [

62] as organizations may hesitate to invest in initiatives without clear regulatory guidance. Additionally, a lack of government leadership and support serves as an external barrier, where inadequate involvement or action from authorities impedes progress toward sustainability goals [

63,

68]. This may include the limited or complete absence of financial or policy-based incentives [

62,

63,

64], such as tax breaks or grants, that would encourage companies to adopt environmentally friendly operations.

Internal barriers originate from within the organization, making it difficult to adopt sustainable practices. Goh, Govindan, Narimissa et al., Perotti et al., Walker et al., and other authors have all agreed that the cost is a significant internal barrier to the implementation of sustainable warehousing [

3,

61,

62,

65,

66]. This includes the initial investment required for sustainable technologies or the cost of switching to a new system [

62], such as energy-efficient lighting, renewable energy sources, and advanced waste management systems, as well as the cost of using environmentally friendly packaging and high costs for disposing of hazardous wastes [

61,

62]. Notably, the cost of environmentally friendly packaging is also treated here as an internal barrier. Although such costs may be driven by external factors (e.g., supplier pricing or market expectations), they are experienced internally, where firms must assess, absorb, and manage these expenses within their budgets and operational strategies.

Transitioning to these sustainable systems or adopting them would also result in continuous expenses for maintenance and operations. Additionally, there is a possibility of interruptions during the transition phase, which will further increase the financial cost. These factors make it difficult to secure adequate financial support for sustainable warehousing initiatives [

62], especially when businesses face intense competition and pressure to keep prices low [

67].

Consequently, the high investment costs and concerns over low return on investment exacerbate this barrier [

62,

68], making it even more challenging for organizations, especially small- and medium-sized enterprises, to prioritize and implement sustainable practices despite their long-term advantages. This situation ultimately hinders the widespread adoption of sustainable warehousing.

Lack of environmental knowledge and information is a significant internal barrier to implementing sustainable warehousing, as highlighted by numerous researchers [

62,

63,

64,

66]. Additionally, Mathiyazhagan et al., Walker et al., Zhu and Geng, and other authors have noted that the lack of skilled technical expertise and a lack of deep understanding of sustainable practices and technologies in many organizations can hinder their ability to develop and execute effective sustainability strategies [

64,

67,

69]. This knowledge gap can result in inadequate planning, poor decision-making, and an inability to fully leverage the benefits of sustainable warehousing. Furthermore, a lack of training and awareness about the importance of integrating sustainability into the supply chain among employees [

3,

63], coupled with insufficient research and development (R&D) capability in green supply chain management practices [

69], can lead to resistance to change and ineffective implementation of sustainable initiatives within organizations. Overcoming this barrier requires investing in education, training programs, and knowledge-sharing initiatives to build the necessary competencies within the organization.

Complexity is an internal barrier to implementing sustainable warehousing, according to many researchers [

61,

62,

70]. The integration of sustainable practices often involves processes that can be challenging to manage and coordinate, adding new layers of complexity to the organization [

70]. This complexity can encompass various aspects, such as adopting advanced technologies and managing increased data requirements for monitoring and reporting sustainability metrics. Additionally, this will require a significant amount of time for all individuals involved [

61]. Overcoming this barrier requires a comprehensive approach that simplifies processes, provides clear guidelines, and ensures robust training and support for all stakeholders.

Poor organizational structure and beliefs can obstruct the implementation of sustainability initiatives [

63,

71]. When an organization’s structure is rigid or not aligned with sustainable practices, driving meaningful change becomes difficult. Additionally, a lack of involvement and commitment from top management can severely limit sustainability efforts [

67,

69]. Without the support and advocacy of senior leadership, these initiatives often lack the necessary resources, direction, and momentum for successful implementation. It is not only top management that matters; a lack of employee engagement can also hinder the success of sustainability programs [

61]. This challenge is often compounded by ineffective communication within the organization, leading to misunderstandings about sustainability goals and practices [

61,

62,

71]. Clear and consistent messaging is essential to align everyone’s efforts and ensure that sustainability strategies are effectively executed.

Table 9 and

Table 10 below provide a summary of the barriers.

4.3. Motivations and Drivers for Sustainable Warehouses

As discussed in the previous section, numerous studies have identified barriers that organizations encounter when implementing sustainable solutions. Additionally, several studies highlight that organizations and their supply chains are under increasing pressure to adopt sustainability practices, examining various factors that impact a company’s ability to implement sustainable practices within their supply chains [

66,

67,

71,

73], with many specifically focusing on sustainable warehouses [

57,

58,

74]. The literature defines these pressures as motivators [

66], drivers [

67,

75], and antecedents [

58].

Saeed et al. defined these drivers as “motivators or influencers that encourage or push organizations to implement sustainability initiatives throughout the supply chain” [

75].

Many international environmental regulations have been established to highlight the importance of using sustainable practices to mitigate the harmful effects caused by companies, industries, and even individuals. These regulations serve as external drivers that encourage the implementation of sustainable practices [

67,

71,

76,

77]. Following the signing of the Paris Climate Agreement in December 2015, for example, which was designed to strengthen global efforts in response to the impacts of climate change, there has been a notable rise in awareness among the public, governments, and companies regarding the imperative of environmental sustainability [

78]. This increased awareness has led to a significant surge in the planning and adoption of sustainable practices within the supply chain. However, as noted in the previous section, uncertain and ambiguous regulations and legislation can also act as barriers to achieving sustainability goals.

Formal assessment processes, such as ISO 14001, are another international regulation that aims to integrate environmental and business management [

69,

73]. This standard promotes a comprehensive approach to environmental and business management, enabling companies and their supply chains to adopt a more proactive stance on environmental issues [

79]. The perceived benefits of implementing ISO 14001 include improving the company’s reputation, enhancing profitability and performance, and raising customer loyalty and trust [

79].

In addition, government support is a critical driver for SSCM [

68,

73,

75]. Policymakers take a proactive approach to introducing and enforcing effective regulations to encourage and guide businesses toward sustainable practices. This support can come in the form of environmental standards and the development of regulations related to social aspects such as labor relations and employment conditions [

75]. These comprehensive measures ensure that businesses not only adopt greener practices but also enhance social sustainability by improving working conditions and promoting fair labor practices while also providing the necessary resources and frameworks to implement these changes effectively.

This growing governmental awareness is evident in various initiatives across Europe, where several countries have set specific energy efficiency targets. Germany, for example, has committed to reducing energy consumption in different industrial and private sectors by 20% by 2020 compared to 2008; looking ahead, Germany aims to cut primary energy consumption by 50% by 2050 [

80]. This drives companies, including their warehouses, to innovate and adopt strategies to achieve these ambitious goals. Among the approaches considered, transitioning toward green supply chains emerges as a key solution to reducing the carbon footprint [

81].

Xin et al. highlight that environmental concerns are not only shared by governments but are increasingly important to consumers as well. According to the literature collected in this contribution, consumer pressure and demand for the environment are among the most significant motivations for sustainable practices, making it impossible for businesses to overlook sustainability in their daily operations [

82]. Similarly, many other authors, including Alzawawi, observed that the companies are actively working to make sure their warehouse operations are sustainable in order to meet customer satisfaction [

63,

82,

83]. This focus on sustainability also reduces the risk of consumer criticism [

67], serving as a significant driver for its implementation in warehousing, as businesses increasingly recognize that environmentally responsible practices align with consumer expectations for ethical and sustainable operations [

67].

Public pressure or societal expectations are also significant drivers that compel organizations to implement sustainable practices [

63,

76,

77], and they are increasingly shaping how warehousing operations are evaluated, both internally and externally. These expectations arise from many interest groups pushing organizations to implement sustainability in their operations in response to growing concerns about problems such as limited resources, climate change, human rights, and many health issues [

76].

Specifically in the context of warehousing, these facilities are not only functional infrastructure but also highly visible representations of a company’s environmental and social responsibility especially when located near residential or urban areas. Issues such as air pollution from delivery trucks, excessive noise, high energy consumption, and labor conditions (e.g., fair wages, working hours, diversity, and safety) are frequently highlighted by local communities, regulators, and the media. Failure to meet public expectations can lead to reputational damage, community resistance, and even protests or regulatory intervention. Unlike other segments of the supply chain, warehouse operations are often more publicly visible and directly linked to community well-being, which increases the likelihood of scrutiny and backlash. This visibility makes social responsibility an operationally significant issue for warehouse managers and a key component of sustainable warehousing. Shareholders, investors, and suppliers also exert pressure on organizations to adopt sustainable strategies through their support and expectations [

64]. Although Alsaawi suggests that suppliers may not serve as primary drivers of sustainability initiatives, they play a critical role in integrating environmental practices into supply chain systems. By actively supporting sustainable practices, suppliers can enhance the efficiency and impact of these practices, contributing to the overall effectiveness of the supply chain’s environmental performance [

84].

The success of implementing sustainable warehousing depends heavily on a firm’s internal motivation. Top management commitment and support are regarded as the most critical internal components [

67,

68,

73]. Leaders play a crucial role by demonstrating positive attitudes, clear visions for sustainability, strategic planning, and strong commitment. Both financial and non-financial support from higher management is essential for successful sustainable warehousing implementation [

58]. Additionally, middle management and employees must also share responsibility and commitment to ensuring the correct implementation of sustainable practices [

67,

73,

85].

This effort must be combined with an organization’s culture that empowers sustainability by embedding sustainable values and fostering leadership commitment [

68]. According to Schrettle et al., cultures that encourage employee participation, develop sustainable norms, and provide acknowledgment for sustainable behaviors enhance motivation [

77]. This includes ongoing education, innovation, sharing opinions and ideas, and a sense of social responsibility [

76]. When sustainability is integrated into the core values and daily behaviors of an organization, employees are more likely to be motivated and committed to sustainable practices.

Cost saving also stands out as a crucial motivator for sustainable warehouses [

66,

84], as the integration of various green practices can significantly yield a long-term reduction in operational expenses [

63], even though the substantial initial investment—discussed in the previous section as a barrier—can be challenging to overcome. Additionally, these practices can enhance overall organizational performance [

67,

85] and offer valuable opportunities to open up new markets. These market openings, in turn, contribute to improved business gains and further financial benefits [

63] and raise the company’s reputation [

67]. Collectively, these factors strongly motivate organizations to adopt sustainable practices.

Sustainability plays an important role in enhancing quality [

63,

67,

74] by reducing waste and pollution [

3,

76,

84], which in turn improves environmental performance and leads to superior quality, which is a key objective for every organization [

63]. Thus, the integration of sustainable practices throughout the supply chain, including warehouses, is also driven by the need to achieve superior quality. Consequently, businesses are driven to adopt and implement sustainable strategies to differentiate themselves and maintain a competitive edge [

67].

Sustainability, according to Perotti et al., is an effective tool for gaining an advantage over competitors, so companies that implement eco-friendly practices as their strategic tools are rising to the top of their industries and setting themselves apart from the competition [

66].

It is important to note that while many authors, including Perotti et al. [

66], Alzawawi [

63], and Walker et al. [

67], have classified competition as an external driver for implementing sustainability, Zimon et al. [

85] present a different perspective. They argue that competition opportunity is considered an internal factor, as it influences internal organizational strategies and initiatives aimed at gaining a competitive edge through sustainable practices [

85]. Whether considered an internal or external factor, it appears to be an important driver in promoting sustainability efforts.

In summary, the current literature extensively highlights the various motivations behind the adoption of sustainable practices within warehouses and supply chains. These drivers can be categorized into internal and external factors. Internal drivers originate within the organization and include the commitment of leadership to environmental goals, the active participation of employees, and the integration of sustainability into the organization’s core mission and long-term strategy. In the context of warehousing, top management commitment directly influences facility design choices, energy consumption strategies, and labor practices.

External drivers, on the other hand, are influenced by factors outside the organization. These include regulatory pressures that require companies to comply with environmental laws, growing consumer demand for sustainable products, and the need to maintain a competitive edge in the market. In warehousing specifically, public and customer expectations increasingly define the standards by which sustainability is assessed, whether through calls for carbon transparency, ethical labor practices, or reduced packaging waste. These external forces drive organizations to adopt visible and measurable sustainability measures at the warehouse level.

Table 11 and

Table 12 below provide a detailed overview of these internal and external drivers, illustrating the various factors that motivate firms to integrate sustainability into their warehousing and supply chain operations.

Finally, while understanding the various motivations for adopting sustainable practices is crucial, it is equally important to recognize the barriers organizations encounter in this pursuit. It is essential to acknowledge that the motivations and challenges faced by organizations in implementing sustainable warehousing practices vary significantly across different sectors [

67]. These differences shape how each organization responds to the challenges and opportunities associated with sustainability. While some may be driven by factors like regulatory demands or customer expectations, others might struggle with internal and external obstacles that slow their progress. Recognizing these sector-specific differences is key to developing effective strategies that address the unique challenges each industry faces.

4.4. Practices and Trends Towards Sustainable Warehousing

Sustainable warehousing is becoming a critical component of modern supply chain management. In this section, the focus shifts to exploring the various strategies, trends, and practical approaches documented in the literature that organizations are adopting to achieve sustainability in warehousing operations. While many of the authors emphasize the environmental dimension, particularly low-carbon or green warehousing as discussed by Ibrahim et al., Korra, and Sadhana [

65,

70], other studies also address the social and economic dimensions, highlighting a more comprehensive approach to sustainability as noted, for example, by Amjed, Harrison, and Malinowska et al. [

6,

56], and many other authors.

Understanding these practices is essential as they not only reflect current trends but also highlight the proactive measures taken by businesses to integrate environmental, social, and economic responsibility into their warehousing operations. Additionally, these measures can help to prevent environmental incidents that may damage a firm’s image, harm its reputation and share price, and lead to customer boycotts or order cancelations [

54].

These practices can be categorized into several main areas: facility design and construction, operational efficiency, energy management, waste management, and green transportation. Each category encompasses multiple activities and trends that contribute to the overarching goal of sustainability. These practices not only reduce overall energy consumption and environmental impact but also enhance social responsibility and economic viability. By exploring these areas, this chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving practices that contribute to sustainable warehousing.

4.4.1. Facility Design and Construction

Implementing the previous sustainable practices in warehouse facility design significantly lowers energy consumption, minimizes waste, and reduces greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in an environmentally responsible warehouse operation. Additionally, these practices positively influence social sustainability by improving employee comfort and safety through ergonomic designs, better air quality, natural lighting, and minimizing noise, which fosters a healthier work environment. Consequently, this leads to better working conditions and higher employee productivity. Although the initial costs may be higher, the long-term economic benefits, including energy savings, reduced maintenance costs, and extended facility lifespan, underscore the comprehensive value of these practices across all dimensions of sustainability.

4.4.2. Operational Efficiency

Automation, robotics, and technologies

Implementing innovation strategies in logistics services [

53], like adopting automated systems and robotics to enhance operational efficiency and reduce energy consumption associated with manual labor [

56].

Implementing advanced sorting and picking systems that optimize workflow and reduce operational delays [

87].

Utilizing technology like RFID devices to track material flow from warehouse receipts can streamline processes, leading to reduced time and energy consumption [

70].

Inventory management

Implementing inventory control systems ensures efficient inventory management, better stock control, reduced waste, and improved operational performance [

50,

66].

Utilizing real-time inventory tracking systems, improving the forecast process, or using just-in-time (JIT) logistics systems [

69] and JIT inventory programs to minimize overstocking and stockouts, thereby reducing waste and improving resource utilization [

6,

53,

56].

Implementing lean warehousing principles to streamline processes and eliminate inefficiencies [

6].

Implementing effective storage policies that optimize space utilization and minimize travel times [

70] and make green supply and purchasing policies [

53,

85].

Optimizing the layout of storage areas and the placement of warehouse equipment [

56].

Employee training, engagement, and well-being practices

Providing continuous training programs to educate employees about sustainable practices and their benefits [

72,

73,

76,

87].

Encouraging employee participation in sustainability initiatives through incentive programs and recognition awards [

56].

Ensuring fair wages and ethical working conditions and adopting transparent, accountable, and responsible management practices [

2].

Health and safety regulations (physical and mental) to prevent work-related injuries, illnesses, and fatalities [

2,

49,

84,

86].

Creating a workforce that represents a variety of demographics, backgrounds, skills, and experiences. This can include diversity in gender, race, culture, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, age, and disabilities [

2].

Sustainable supply chain management

Incorporating supplier sustainability assessment and efficient supplier selection process to ensure that partners meet environmental, social, and ethical standards [

67,

69,

82,

85].

Integrating iso 14001 into environmental management practices supports both organizational sustainability and employee engagement [

72,

79]. Additionally, sourcing from suppliers with ISO 14000 certification [

69].

Implementing the above sustainable practices in warehouse operations is essential for reducing resource consumption and waste, thereby enhancing environmental sustainability. These practices also support social sustainability by reducing physical strain on workers, minimizing the need for excessive labor, and fostering a safer work environment through targeted training programs. Economically, improving operational efficiency leads to lower operational costs. By streamlining processes, reducing errors, and optimizing inventory management, companies can achieve substantial cost reductions, contributing to overall profitability and long-term financial stability.

4.4.3. Energy Management

Adopting the previously mentioned effective energy practices is crucial for sustainable warehousing. Implementing renewable energy sources and energy-efficient technologies, such as LED lighting and smart thermostats, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, thereby enhancing environmental sustainability. Moreover, these practices contribute to the broader social goal of reducing pollution and combating climate change, which positively impacts public health and community well-being. Economically, energy management practices yield significant benefits by lowering utility costs and leveraging government incentives for renewable energy, leading to further financial savings.

4.4.4. Waste Management

Effective waste management is essential for sustainable warehousing, as implementing the practices mentioned earlier can greatly reduce the environmental impact of warehouse operations. Socially, proper waste management enhances workplace safety and fosters a healthier environment for both employees and surrounding communities. Furthermore, it supports broader social sustainability efforts. Economically, efficient waste management reduces disposal fees and can generate revenue from recycling. Moreover, companies that demonstrate strong waste management practices often enjoy a positive reputation, which can translate into competitive advantages.

4.4.5. Green Transportation

Fuel-efficient vehicles

Adopting fuel-efficient or alternative fuel vehicles (electric vehicles) for transportation needs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pollution fuel consumption [

2,

72].

Using automated guided vehicles (AGVs) enhances sustainability by reducing emissions, minimizing waste, optimizing warehouse space, and improving energy efficiency in operations [

50].

Usage of eco-friendly transportation forklift trucks and any other internal transport equipment [

6,

85].

Route optimization

Using advanced route planning software to minimize travel distances and reduce fuel consumption and emissions [

88].

Designing picking zones and consolidating shipments to maximize vehicle load efficiency and reduce the number of trips required [

56].

Integrating green transportation into warehousing operations—through the methods previously discussed—substantially reduces the carbon footprint of logistics activities, thereby promoting environmental sustainability. By cutting emissions and improving fuel efficiency, green transportation initiatives contribute to better air quality and a healthier environment for communities. This, in turn, enhances a company’s reputation and strengthens community support, as businesses adopting sustainable practices are viewed more favorably. Economically, green transportation can lead to significant savings in fuel and maintenance costs. Moreover, companies that implement these practices are better positioned to comply with evolving regulatory standards, potentially avoiding fines and benefiting from tax incentives.

In summary, the practices and trends highlighted in this section reflect the diverse strategies, practices, and proactive measures organizations are taking to integrate sustainability into their warehousing operations. These practices not only address the environmental impacts of warehousing operations but also enhance social sustainability and drive economic efficiency. Industry practitioners, policymakers, and researchers can use these practices as invaluable tools for identifying opportunities to reduce costs, manage risks, create new products, and facilitate essential cultural and structural changes [

81], ultimately enhancing sustainability in warehousing. Recognizing the importance of these practices and understanding their multifaceted impact is crucial for developing effective and comprehensive approaches to sustainable warehousing that meet the evolving demands of the global supply chain.

5. Discussion

This study sets out to explore sustainability in warehousing by identifying key drivers, barriers, and best practices for transitioning to sustainable warehouse operations. Given the increasing environmental concerns, the role of warehouses within supply chains has gained significant attention due to their energy-intensive processes and potential for sustainability improvements. By synthesizing insights from the literature, this study has developed a structured framework that addresses the complexities and opportunities in sustainable warehousing.

Aligned with RO1, this study provides an overview of the current state of the art in sustainable warehousing by identifying the primary factors that influence sustainability in warehouse operations. The findings reveal that warehouses perform various value-added services, including packaging, labeling, testing, assembly, manufacturing, and recycling, that consume substantial amounts of energy. However, when executed sustainably, these activities can significantly reduce overall energy consumption and GHG emissions while also improving social and economic outcomes. Warehouses that integrate sustainability measures not only lower their carbon footprint but also enhance employee well-being and contribute positively to their surrounding communities.

In response to RO2, this study develops a comprehensive framework for integrating sustainability into warehousing operations. This framework serves as a strategic tool for guiding warehouses through the sustainability transition, as shown in

Figure 5 below, which integrates the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability and follows a structured, continuous improvement process.

The framework follows a systematic approach that begins with a three-dimensional sustainability assessment to evaluate a warehouse’s current sustainability performance. This initial step identifies areas for improvement and establishes a baseline for sustainability enhancements. The assessment employs various approaches, such as energy audits, carbon footprint analysis, and employee surveys, to ensure a holistic evaluation.

Following the assessment, the framework transitions to an analysis of drivers and barriers that influence sustainability adoption. Internal and external drivers, such as regulatory requirements, cost-saving opportunities, and stakeholder expectations, propel warehouses toward sustainability. Conversely, barriers—including high upfront costs, technological limitations, and resistance to change—pose significant challenges. The framework visually represents these opposing forces to highlight the complexities of achieving sustainability goals.

Based on this analysis, customized solutions are developed and implemented, tailored to the warehouse’s operational context and the identified drivers and barriers. These solutions include both technological and organizational adjustments designed to improve performance across the environmental, economic, and social dimensions.

Importantly, the adoption of sustainable solutions often necessitates changes in managerial decision-making practices. To effectively embed sustainability into operations, managers must begin incorporating sustainability-related key performance indicators (KPIs) into routine assessments such as energy use per order, carbon footprint per shipment, or employee well-being metrics. This shift requires organizations to reevaluate traditional priorities, moving from a short-term focus on cost reduction toward long-term value creation and risk mitigation. Additionally, procurement and supplier selection strategies may be revised to prioritize partners with sustainability certifications or transparent emissions data.

This transformation reflects a more holistic and strategic managerial approach to warehouse management, balancing operational efficiency with environmental and social responsibility.

This management shift enables the implementation of a wide range of best practices. Examples include optimizing energy use through renewable sources, adopting automation and robotics to enhance resource efficiency, and implementing waste reduction strategies. Social sustainability initiatives, such as employee engagement programs, fair labor practices, and improved working conditions, also play a crucial role in fostering a sustainable warehouse culture.

A key aspect of this framework is its cyclical nature, emphasizing continuous improvement. Sustainability efforts are not static but evolve based on periodic reassessments. This iterative process ensures that warehouses remain adaptable to changing conditions, regulatory landscapes, and technological advancements.

The primary focus of this framework is on warehouses; however, to promote comprehensive sustainability across the entire supply chain—not just in warehousing—its principles, practices, and strategies can be adapted to encompass every stage of the supply chain through the final step: Supply Chain Sustainability Integration. This step ensures that sustainability is seamlessly embedded into each phase, spanning from raw material sourcing and production through warehousing and distribution to the recycling or disposal of products at the end of their life cycle. This broad application strengthens the sustainability of the entire supply chain, shifting the focus from isolated warehouse practices to an integrated end-to-end approach.

By systematically addressing these steps, the framework provides a structured approach for integrating sustainability into warehousing operations, thereby fulfilling RO2 and offering both theoretical and practical contributions to the field.

5.1. Key Findings and Implications

The findings suggest that the transition to sustainable warehousing is primarily driven by regulatory pressures, cost-efficiency measures, and growing stakeholder expectations. Environmental regulations, both existing and emerging, serve as a major catalyst for companies to adopt sustainable practices. Additionally, warehouses that optimize energy consumption and waste management can realize significant cost savings, making sustainability an economically viable strategy.

However, several barriers hinder implementation. High initial investments in sustainable infrastructure, such as solar panels and energy-efficient technologies, often deter companies from making the transition. Moreover, organizational challenges—such as lack of commitment from leadership and resistance from employees or suppliers—further complicate sustainability efforts. Addressing these barriers requires a multi-stakeholder approach, ensuring alignment between regulatory bodies, supply chain partners, and warehouse operators.

Identified sustainable practices in warehousing encompass a range of strategies aimed at reducing environmental impact, improving operational efficiency, and enhancing social well-being. Energy-efficient building designs, including improved insulation, LED lighting, and automated climate control systems, help minimize energy consumption while maintaining optimal working conditions. The integration of renewable energy sources, such as solar panels and wind turbines, further reduces dependency on non-renewable energy and lowers greenhouse gas emissions. Waste reduction initiatives, such as implementing circular economy principles, optimizing packaging, and adopting recycling programs, contribute to both environmental sustainability and cost efficiency. Additionally, sustainable transportation and logistics strategies, including route optimization, electric vehicle adoption, and load consolidation, help lower fuel consumption and emissions. Employee well-being is also a critical aspect of sustainable warehousing, with companies investing in ergonomic workspaces, safety training programs, and fair labor practices to ensure a healthier and more productive workforce. By systematically adopting these practices, warehouses can achieve a more sustainable operational model that balances environmental responsibility, economic efficiency, and social equity.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the research is based solely on a literature review, with no primary data collection through interviews or real-life case studies. While the review provides valuable insights, it inherently lacks the empirical depth and generalizability that primary data would offer. Conducting case studies on warehouses that have successfully implemented sustainable practices would provide deeper insights into practical challenges and solutions, bridging the gap between theory and real-world application. Future research could benefit from a mixed-methods approach that integrates quantitative data, such as sustainability performance metrics. This would enable a more comprehensive evaluation of sustainable warehousing practices and provide a more practical understanding of their real-world effectiveness.

Secondly, the study lacks data on the integration of sustainability with emerging technologies, particularly AI. AI has the potential to transform warehouse sustainability by optimizing energy use, enhancing predictive maintenance, and improving supply chain efficiency. However, due to the limited available literature on this intersection, AI’s role in sustainable warehousing remains underexplored. Future research may investigate AI-driven solutions and their impact on sustainability efforts.

Another limitation is the geographical scope of the study. While sustainability is a global concern, warehousing practices, regulations, and challenges vary across regions due to differences in economic conditions, infrastructure, and policy frameworks. A more region-specific or comparative analysis across different countries could provide a more nuanced understanding of sustainability in warehousing.

Future research should focus on assessing the long-term impact of sustainable warehousing practices across different industries and geographical regions. Investigating how these practices yield tangible benefits for businesses, employees, society, and the environment through empirical studies and real-world case analyses will be crucial in refining sustainability strategies. Furthermore, digital and technological advancements will play an increasingly vital role in shaping the future of sustainable warehousing. Technologies such as blockchain, automation, the Internet of Things (IoT), and AI offer immense potential for optimizing warehouse operations, improving resource efficiency, and reducing environmental impact. While this contribution did not extensively explore AI due to limited research at the intersection of AI and sustainability, future studies should examine its potential. AI, for instance, could revolutionize warehouse management by enabling real-time monitoring, data-driven decision-making, predictive analytics, and automated energy management.

Another promising direction is the growing emphasis on circular economy principles, which will likely reshape warehouse operations by increasing the need for reverse logistics, material recovery, and closed-loop supply chains. Understanding how warehouses can effectively support circular economic strategies will be crucial in reducing waste and maximizing resource efficiency. Moreover, future studies should examine the economic feasibility of sustainable warehousing, assessing the long-term cost–benefit analysis for companies investing in green technologies and infrastructure. Beyond environmental and economic considerations, the social impact of sustainable warehousing should also be a focal point, with research exploring how employee well-being, job satisfaction, and skill development are influenced by sustainable warehouse practices. Finally, given the rapid evolution of sustainability trends, longitudinal studies tracking the progress of sustainable warehousing over time would provide valuable insights into long-term challenges, best practices, and industry adaptations. By addressing these gaps, future research can contribute to the ongoing development of more resilient, efficient, and sustainable warehousing systems.

6. Conclusions

As global attention to sustainability continues to grow, warehousing will undergo significant transformations to meet rising environmental, economic, and social expectations. This contribution has provided a strong foundation for understanding the key drivers, barriers, and practices that define sustainable warehousing today. However, the path to fully sustainable warehousing is an ongoing journey that requires continuous innovation, deeper integration of advanced technologies, and collaborative efforts across industries to address emerging challenges and opportunities.

Additionally, policy and regulatory developments will shape the landscape of sustainable warehousing in the coming years. Governments are likely to introduce stricter environmental standards, requiring companies to adopt greener practices while also considering financial incentives such as tax breaks and grants to encourage sustainability adoption. Raising awareness through industry collaborations, conferences, and educational initiatives will further drive the transition toward sustainable supply chain management.

Businesses must remain agile, not only to comply with evolving regulations but also to leverage sustainability as a competitive advantage. Companies that proactively invest in sustainable warehousing can achieve cost savings, operational efficiencies, and enhanced reputations among consumers and stakeholders. Moreover, the social dimension of sustainability is becoming increasingly important. Warehousing operations that prioritize employee well-being, safety, and inclusiveness will gain a strategic advantage, as a healthier and more engaged workforce contributes to long-term organizational success. Future research should explore how warehouse design, automation, and sustainability-driven policies impact employee satisfaction, retention, and overall productivity.

While this study contributes valuable insights into sustainable warehousing, the field remains dynamic, with new challenges and opportunities constantly emerging. Ongoing research will be critical to adapting to technological advancements, regulatory changes, and shifting societal expectations. Businesses that integrate sustainability into every facet of their operations and collaborate with industry stakeholders will be at the forefront of shaping the next generation of sustainable supply chains.

Achieving a truly sustainable future for warehousing, and for entire supply chains requires a shared commitment among industry leaders, researchers, and policymakers. Through continuous innovation, collaboration, and dedication to sustainable development, industry can drive meaningful changes that benefit not only businesses but also society and the planet as a whole.