1. Introduction

Knowledge sharing is a basic component of organizational success and innovation, even if cultural obstacles, lack of trust, and inadequate technology infrastructure still constitute major international issues [

1]. Effective knowledge sharing, especially in information-intensive industries, enhances cooperation, raises output, and supports continuous education [

2]. Even though most past businesses employed unofficial channels, digital transformation, enterprise social media, and AI-driven platforms have become indispensable in allowing for information flow [

3]. Nevertheless, challenges include intellectual property rights and a reluctance to distribute tacit knowledge, therefore impeding progress [

4]. Strategic leadership and a knowledge-sharing culture overcoming these challenges define sustainable development in the modern corporate environment [

5].

Organizational cultures are greatly influenced by leadership styles, which, in turn, influence employees’ desire to share knowledge: a quality essential for innovation and obtaining a competitive edge [

6]. Particularly, leaders who stress involvement and transformation create a transparent atmosphere where staff members feel appreciated and free to provide their knowledge [

7]. But human capital which comprises workers’ knowledge, experience, and skills often serves as a middle ground between information flow and its value [

8]. A strong basis of human capital improves information flow by encouraging trust, teamwork, and a development attitude [

9]. Though their value is great, little is known about the relationship between transactional leadership style and human capital, even if they could improve information exchange [

10]. This study aimed to shed light on efficient leadership strategies for knowledge-driven companies by means of an analysis of the interaction between several leadership style and knowledge sharing initiatives via the mediator role of human capital.

Intellectual capital consists of useful things that make an organization more valuable and able to compete [

11]. There are three main things in it: human capital, structural capital, and relational capital. Employees each contribute knowledge, skills, experience, and creativity to human capital [

12]. The supporting resources in an organization such as workflows, databases, and company values, are all part of structural capital [

13]. Relational capital is the benefits that come from our contacts with customers, partners, and others in the industry [

14]. Weighted equally, these factors underlie the process of innovation, exchange of learning, and sustainability in any organization.

Despite extensive study on this issue, there is a scarcity of studies examining the mediating function of human capital in the relationship between information flow and leadership styles [

15]. Most studies investigated how transformational and participative leadership promotes information sharing [

16], and fewer attention to employees’ skills, knowledge, and intelligence was provided. Furthermore, most past studies have found human capital to be a natural result of good leadership rather than a complicated element influencing employees’ motivation and capacity to share knowledge [

17]. Bridging this knowledge gap depends on research on how various leadership styles indirectly promote knowledge sharing via human capital since knowledge-driven projects are ever more important for companies. This knowledge gap can provide a path to build leadership structures that inspire people to participate in critical and creative thinking, therefore promoting an always-learning and development culture.

This study aimed to investigate how transactional leadership affects knowledge sharing inside companies, particularly examining the mediating role of human capital. This research aimed to provide companies with useful insight on creating leadership practices that support human capital development and information exchange. By clarifying the interaction between leadership and human capital in supporting information-sharing activities inside knowledge-intensive contexts, this paper intends to improve both theoretical and managerial viewpoints.

The findings can show that although transactional leadership greatly improves the development of human capital, it does not instantly affect intellectual property sharing. Workers with more knowledge and experience engaging in activities involving knowledge sharing is quite important. Moreover, our findings also show that the increase in human capital exactly corresponds with the degree of effectiveness of leadership in knowledge management.

The study provides theoretical understanding by demonstrating how transactional leadership indirectly affects knowledge sharing via human capital. This study, unlike earlier research primarily concentrating on the direct impact of leadership styles on behaviors, substantiates the Resource-Based View (RBV) by demonstrating that enhancing knowledge sharing behaviors necessitates investment in employees’ skills and competences. Second, the study adds to the corpus of empirical data in the leadership literature by demonstrating how transactional leadership advances the growth of human capital. The findings support prior research [

18] demonstrating how leadership approaches facilitated staff members to grow in their competency. Although earlier studies show a clear link between transactional leadership and knowledge sharing, this study further indicates that human capital mediates the examined link and offers a deeper perspective on the effectiveness of leadership in the knowledge management. Third, this work adds to the corpus of knowledge by attending to a need for further dynamics of knowledge sharing and leadership.

The upcoming sections are arranged in the following way. The literature review part delineates the theoretical and empirical literature. The literature review ultimately underpins the hypothesis development section. The methodology section delineates the data, sample, and variables along with their measurements. The results section delineates the findings, which are subsequently analyzed in the ensuing part. The report concludes with a discussion of policy implications and constraints.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Transactional leadership within the leadership theory emphasizes clearly defined roles, rewards, and sanctions to ensure compliance and efficiency [

19]. This leadership approach is intricately linked to the Social Exchange Theory [

20], which asserts that employees participate in reciprocal relationships grounded in rewards and obligations. Transactional leaders delineate clear expectations and motivate staff to disseminate their expertise throughout the organization via knowledge exchange [

21]. This exchange-based relationship may sometimes obstruct voluntary information sharing, since employees may prioritize extrinsic incentives above intrinsic drive [

22].

The Resource-Based View (RBV) Theory [

23] promotes information sharing by highlighting human capital as a crucial resource for achieving competitive advantage. In organizations, knowledge sharing improves overall performance, fosters innovation, and enhances competence [

24]. Transactional leaders may enhance this process by establishing systematic procedures, including training programs, performance-based incentives, and standardized knowledge-sharing platforms. Although often viewed as inflexible, transactional leadership can proficiently facilitate knowledge transfer when it is matched with explicitly stated goals and strategic human resource policies.

The intermediary function of human capital in the association between transactional leadership and knowledge sharing is further clarified by human capital theory [

25]. Knowledge sharing programs begin with the employees’ competencies: skills, knowledge, and experience. Transactional leaders promote human capital development by guaranteeing ongoing learning, skill enhancement, and organized career growth opportunities. Employees are more likely to participate in these activities when they believe their knowledge-sharing contributions are appreciated and rewarded, thereby enhancing the company’s intellectual capital and sustainable performance.

Despite this, there is also evidence of a connection between transformational leadership (TFL), transactional leadership (TSL), and organizational performance, with some exceptions [

26]. Several researchers [

27,

28] looked at transactional leadership as a distinct kind of leadership. The foundation of transactional leadership is based on the idea of two-way communication and cooperation between superiors and those who report. The word refers to the managerial–subordinate relationship in which monetary, political, and psychological rewards are given in exchange for fulfilling targets [

29]. Leaders in transactional leadership seek to satisfy the material and psychological requirements of their subordinates in return for the performance outcomes the leader has set for them [

30]. In contrast, followers of a transactional leader are obligated to accept and execute the leader’s commands in return for some kind of remuneration, access to resources, or protection from negative consequences. Transactional leadership, on the other hand, is focused on the here and now rather than the long term, and it often leads to wasted time due to negotiation rather than production as leaders seek out critical information or subordinates have specialized issue solving abilities. It is a more hands-off style of management that involves keeping an eye out for issues and making adjustments as necessary. As a consequence, followership under such a leader stifles the expansion of workers’ capacity for original thought and creativity, which in turn stunts both individual and collective advancement [

31].

Knowledge, as shown by [

32], is an organization’s most valuable strategic asset, having the potential to provide businesses an edge in a highly competitive and rapidly changing environment. In today’s competitive business environment, knowledge is king [

33]. As such, it is crucial to pay attention to knowledge management, which involves coordinating efforts to produce, disseminate, and use information [

34]. Organizations depend on their employees and training processes to ensure they can continue to compete successfully. Knowledge management is a system whose primary purpose is to choose and/or assist personnel in acquiring specialized knowledge, skills, and talents [

35]. The goal of a knowledge management system is to facilitate the sharing of information and expertise among its participants. Knowledge sharing, either within a team or between teams, is critical for organizations to build skills and capabilities, increase value, and maintain competitive advantage [

36]. Knowledge sharing behavior is the foundation upon which employees can make contributions to the applications of knowledge, innovation, and organizational optimization. Hence, the importance of information sharing in the results of knowledge management is growing. Due to the high potential returns on investment associated with information sharing, several businesses devoted substantial resources to its management [

36].

The terms knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange are not synonymous with knowledge sharing [

37]. Knowledge transfer includes both the transmission of and the learning of knowledge, even though knowledge exchange has been used synonymously with knowledge sharing. The term knowledge transfer is used to characterize the sharing of information across various departments, companies, and other entities [

38].

Unlike communication, the distribution of knowledge is closely tied to it. As it requires a cognitive subject, knowledge cannot be freely distributed in the same way that things may be. The ability to reconstruct one’s conduct is crucial for absorbing the information presented by others. In doing so, it facilitates the exchange of information and expertise. For knowledge sharing to occur, at least two people must be involved; one must already be knowledgeable, while the other must be eager to learn [

38].

The fundamental features of knowledge sharing can be summarized from its description above as follows. Knowledge sharing is characterized by the following four characteristics: (1) it is a major individual behavior; (2) it is a voluntary, proactive, behavioral awareness; (3) it is governed by environmental systems or processes, such as law, ethical standards, and codes of conduct, and habits; and (4) it leads to the joint occupation of a topic by two or more people [

39].

Many empirical studies investigated the relationship between transactional leadership and information sharing, therefore highlighting both its benefits and disadvantages [

40]. Through contingent rewards and active management-by-exception, transactional leadership—which [

26] found to enhance knowledge sharing behaviors when employees view reward systems as fair and transparent—can help. Likewise, ref. [

29] found that transactional leadership improves knowledge exchange in structured environments with clear criteria and incentives. Still, several studies, including those by [

41], show that transactional leadership may have a limited impact on voluntary knowledge sharing activities, largely because of its focus on extrinsic compensation over intrinsic tendency. Organizational culture and degrees of trust affect how effectively transactional leadership promotes information sharing [

30]. The mixed results show that although transactional leadership can encourage knowledge sharing via organized procedures and incentives, it may be less successful in fostering an open and voluntary knowledge exchange free from additional leadership styles or supporting organizational environments [

42].

Leaders are crucial to the success of an organization’s information sharing efforts [

43]. Knowing that they will be financially rewarded and publicly acknowledged for their contributions to the organization’s success is a strong incentive to share what they know [

44]. According to the research on leadership, effective managers and executives actively promote the dissemination of information across their organizations [

44]. Knowledge sharing in enterprises is crucial for maintaining a competitive edge and contributing to a dynamic economy [

45]. In today’s competitive landscape, staffing for skills, choosing for expertise, and training for competencies is insufficient; it is also essential to facilitate the transfer of information and expertise from tenured professionals to newcomers in the sector [

46]. By encouraging people to share their expertise both inside and across teams, businesses may better use their knowledge base [

47].

Additionally, research [

47], showed a significant correlation between workers’ self-reported information sharing and their perceptions of their managers’ knowledge and skill as well as their ability to regulate incentives for desired behavior. Both the agency theory and the social exchange theory demonstrated the significance of management endorsement of knowledge sharing and the close link between the two [

48]. Managers help workers by coordinating the support of leaders and employees to provide incentives, objectives, and precise tasks, with the transactional behavior leaders’ style being the most successful [

49]. Transactional leadership style would be the method that permits knowledge sharing and knowledge to be exchanged effectively across the business as the incentive system was created to motivate workers for knowledge sharing purposes in numerous organizations [

49].

In addition, ref. [

50]’s research revealed a strong connection between information sharing and contingent payment. Lack of rewards, and recognition has been mentioned as an impediment to information sharing and is recommended for establishing the sharing culture and facilitating knowledge sharing [

51]. When there is strong leadership, those who follow are inspired to work together toward a common objective. Other research [

52] highlighted that leaders’ styles significantly influenced employees’ willingness to share information and their desire to do so. Knowledge sharing describes how effective leaders foster an environment of open dialogue and exchange of information by using a variety of means [

50].

Organizational knowledge management is mostly ineffective without the involvement of top-level leaders [

50]. Leaders enable the transformation of knowledge into comparative advantages by providing the vision, motivation, procedures, and structures necessary for employees at all levels of the firm [

53]. Managers at all levels of an organization need to make an effort to manage the three essential knowledge processes of producing, sharing, and using information to effectively manage knowledge. The theories of transformational and transactional leadership give a framework for comprehending the role that leaders play in the development of expertise [

53].

Future insights of leaders and organizations would benefit greatly by investigating the part that leadership styles play in translating knowledge into strategic benefits. Scholars in the field of strategy have started to sketch out a knowledge-based vision of the company, which holds that efficient knowledge management inside an organization may provide businesses an ongoing advantage in the marketplace [

53,

54]. In contrast to the physical and financial resources, these thinkers assert that intangible expertise resources are where a company’s competitive advantage is found. Achieving and maintaining a competitive advantage depends on the knowledge processes inside a business being directed effectively [

54]. On the ground of the previous theoretical and empirical literature, we developed the following hypothesis.

H1: Transactional leadership is positively related with knowledge sharing.

Extensive empirical studies on the link between transactional leadership and human capital have been conducted underlining the need for leadership strategies to raise employee competency [

55,

56]. Through contingent rewards and performance-based incentives, ref. [

57] discovered that transactional leadership improves staff skill development and competency acquisition. The study improves human capital accumulation by utilizing specified performance goals and organized career development initiatives. While transactional leadership guarantees immediate skill development, experts like [

58] contend that it may not sufficiently encourage long-term employee innovation and creativity, which are vital for the increase in human capital. Recent research, most notably by [

59], indicates that the effectiveness of transactional leadership in human capital development is influenced by organizational support systems including training programs and career progression chances. The findings show that although the development of human capital depends on transactional leadership, its efficacy is increased when combined with supporting organizational structures and complementary leadership approaches. Transactional leadership behavior plays a crucial role in establishing clear expectations, conducting contract negotiations, delineating responsibilities, and conferring rewards and recognitions that are linked to the achievement of organizational goals. The establishment of objectives and corresponding performance standards that are expected of leaders and their followers [

60]. According to [

61], there is a focus on the importance of the interdependence and exchange that occur between leaders and their followers. Transactional-oriented leaders are capable of motivating their team members to come up with innovative ideas by providing tangible forms of appreciation or incentives for fruitful initiatives, as well as by supporting imaginative concepts. Essentially, this approach aims to reveal the leader’s commitment to the cooperative pursuits of their subordinates.

Effective leaders exhibit a keen understanding of the importance of fostering staff development, an indispensable element for facilitating organizational change [

62]. To maintain the enduring expansion of intellectual capital, a multitude of organizations dedicate resources to the advancement of their personnel [

63]. Leadership strongly affects intangible assets. For this reason, in any organization, leadership is regarded as a crucial element. Primarily, leadership holds the human capital of enterprises. Somehow, when construed as a procedure for leadership improvement, leadership becomes an intellectual capital constituent [

64]. As such, leadership directs the attention of a person toward human interaction alongside their behavior and capital.

Transactional leadership is a leadership approach that primarily utilizes contingent reward exchanges as a means of motivating community members [

65]. On the ground of the previous theoretical and empirical literature, we developed the following hypothesis.

H2: Transactional leadership has a significant positive relationship with human capital.

Human capital and information exchange show a strong correlation, therefore stressing the influence of employees’ skills, experience, and knowledge-sharing capacity on their willingness and capacity to interact [

66]. Higher degrees of human capital employees are more likely to participate in knowledge sharing events, ref. [

67] discovered since they see their experience will help the business to flourish. Likewise, ref. [

68] underlined that human capital—especially concerning education and professional experience—increases people’s confidence and drive to share information. According to [

69], companies with highly qualified employees show more efficient knowledge sharing policies, hence improving performance and creativity. Some studies, such as [

70], contend that information hoarding results from employees limiting knowledge sharing given their competitive advantage as expertise. Recent studies by [

59] show that the change of human capital into efficient knowledge-sharing activities depends critically on organizational culture and leadership. These findings highlight how important both personal capacity and organizational assistance are to developing a knowledge-sharing culture. On the ground of the previous theoretical and empirical literature, we developed the following hypothesis.

H3: Human capital is positively related with knowledge sharing.

Empirical studies [

71,

72] show that human capital significantly mediate the link between transactional leadership and knowledge sharing, therefore highlighting its impact on the conversion of leadership styles into knowledge sharing activities. Transactional leadership improves human capital by utilizing organized training, skill development, and performance-based incentives, thereby fostering employees’ inclination to share information [

73]. Moreover, research by [

74] implies that although transactional leadership offers a structure for methodical information flow, its value primarily depends on the degree of human capital in the company. According to [

70], workers with significant human capital may sometimes hide information if they believe it would be a tool for power or a means of competitive advantage. Recent research underlines how organizational culture and leadership support can improve the mediating function of human capital, therefore ensuring that deliberate leadership programs result in efficient knowledge-sharing mechanisms. The findings show that transactional leadership by itself will not be enough to foster knowledge sharing without deliberate development and application of human capital inside the company. On the ground of the previous theoretical and empirical literature, we developed the following hypothesis.

H4: Human capital places an underlying role between transactional leadership and knowledge sharing.

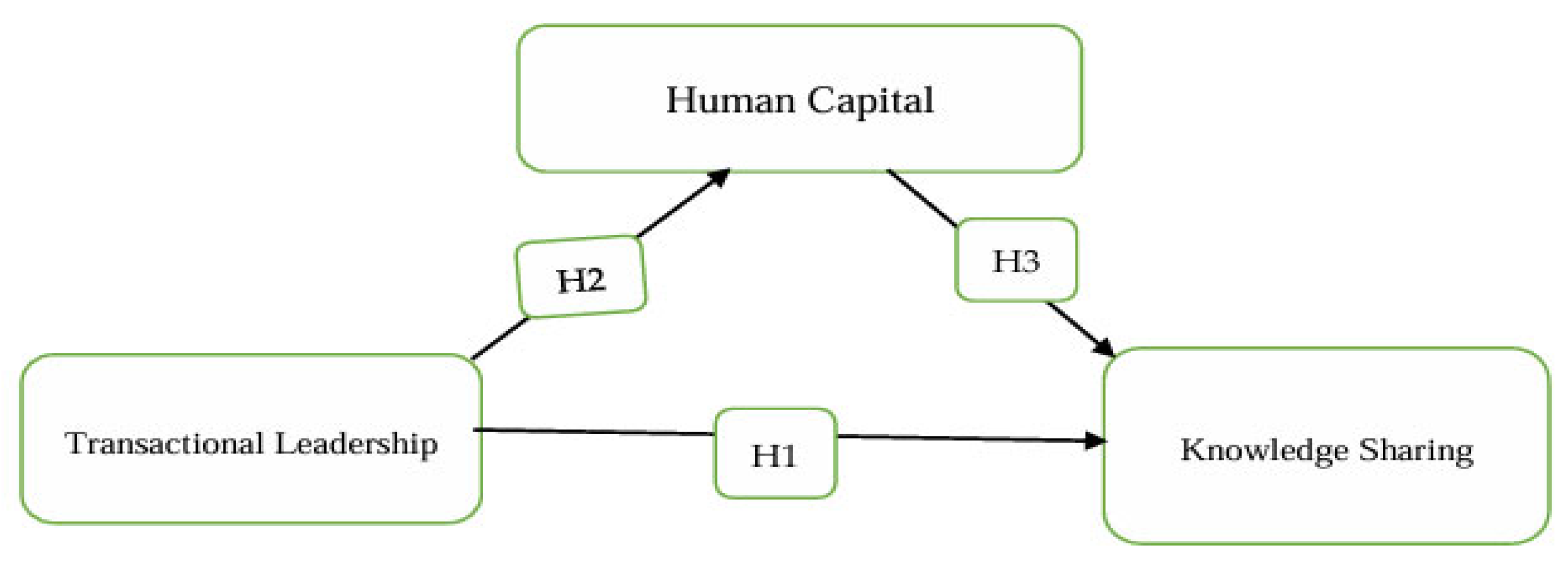

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of the study drawn on the ground of the gap extracted from previous studies.

4. Results and Findings

Table 2 shows the demographic data of the respondents. It illustrates that the majority of workforce is male, and the largest group of employees are between 28 to 37 years old. The table also shows that employees are well-educated, in the mid-career, and in the middle grade of employment.

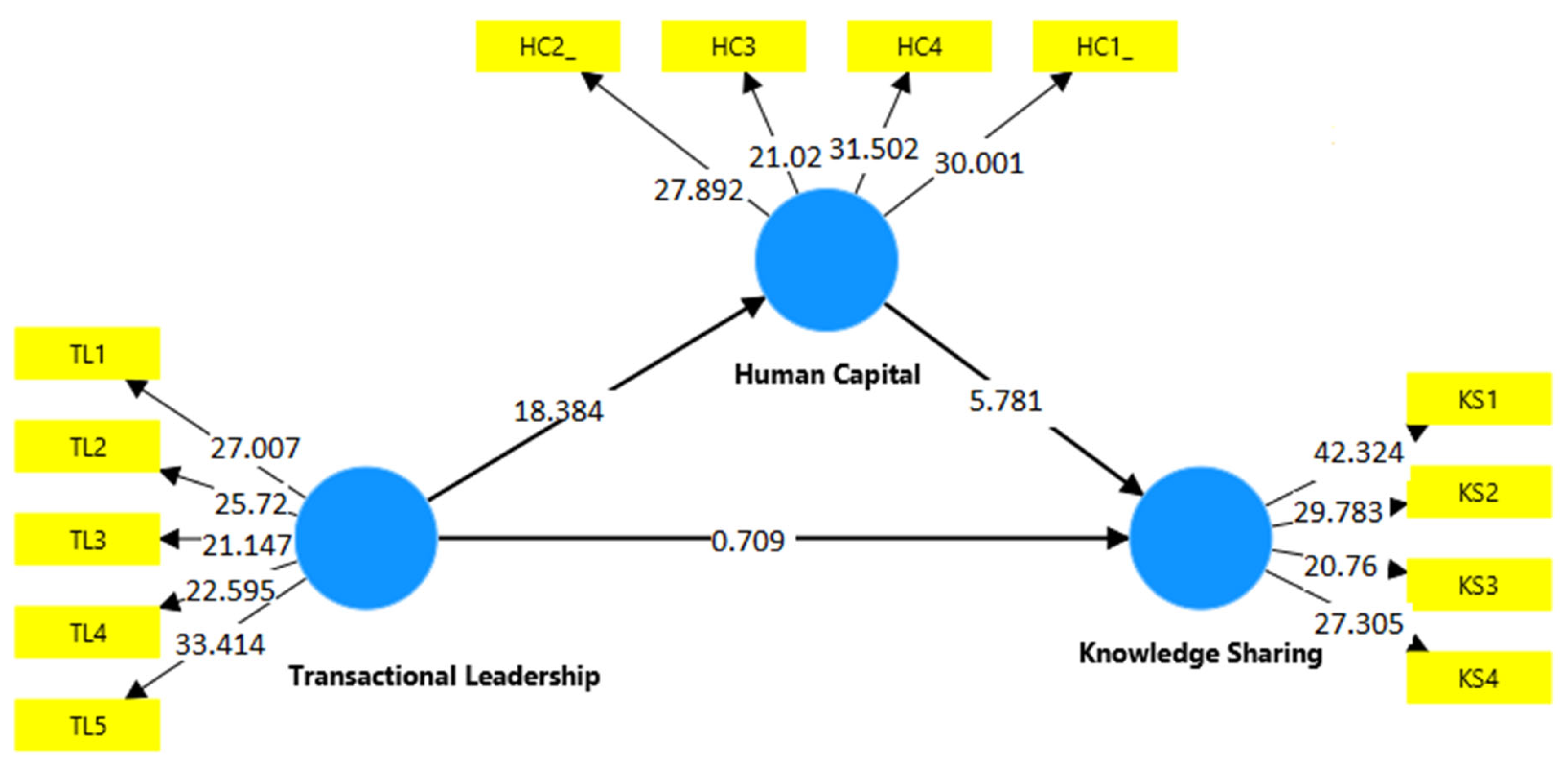

Table 3 shows the factor loadings of the measuring items for transactional leadership, knowledge sharing, and human capital. The loadings show the degree of correlation between every item and corresponding latent concept. Every item shows suitable loading values over the advised threshold of 0.70 indicating robust idea validity. Strongly reflecting this construct, the elements of human capital have loadings between 0.742 and 0.796. Loadings ranging from 0.731 to 0.838 for the knowledge sharing items confirm their dependability in evaluating knowledge-sharing behavior. The transactional leadership items show notable loadings ranging from 0.716 to 0.808, therefore implying that these items quite capture the essence of transactional leadership. These results imply that the measurement model has strong dependability, therefore ensuring that the chosen items reflect their related constructs.

Table 4 shows the results of the reliability and validity examination of the constructs using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), rho_c, and average variance extracted (AVE). All of the human capital (0.7819), knowledge sharing (0.7977), and transactional leadership (0.8096) items show strong internal consistency according to Cronbach’s alpha results; all of the above the advised limit of 0.70. For every construct, the composite reliability (CR) ratings show values over 0.70, therefore verifying the accuracy of the measuring technique. The rho_c values above 0.85 indicate the constructive validity. The AVE marks for transactional leadership (0.565), knowledge sharing (0.6252), and human capital (0.6047) are all above the 0.50 mark. These results show both construct validity and dependability, therefore confirming that the measuring technique is appropriate for more research.

Using the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) matrix and the Fornell–Larcker criterion,

Table 5 and

Table 6 evaluate discriminant validity.

Table 5 shows, from HTMT data, the degree of variation among buildings. Human capital and knowledge sharing have an HTMT score of 0.5929; knowledge sharing and transactional Leadership have an HTMT score of 0.4305, all of which are below the advised level of 0.85, hence suggesting appropriate discriminant validity. With an HTMT score of 0.8595 between human capital and transactional leadership, the score somewhat surpasses the threshold and indicates a possible overlap between the two spheres.

Table 6 shows the Fornell–Larcker criterion by first contrasting the square root of the AVE (diagonal values) against the inter-construct correlations (off-diagonal values). Verifying discriminant validity—especially, human capital = 0.678, knowledge sharing = 0.789, and transactional leadership = 0.754—the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeds its correlation with other constructs.

Table 7 shows the cross loadings of the items. The cross loadings of each item are sufficient that validate the hypothesis testing in the analysis. The cross loading of items in the tables verify the discriminant validity of the construct that are built on the ground of the previous literature.

Table 8 shows the VIF values that show collinearity among selected items of the construct. The data were satisfactory if they showed the absence of the collinearity among the items. If there was collinearity, then first removed it, and then analyzed the results.

Showing same values across all criteria,

Table 9 offers model fit indices for both the saturated and estimated models, suggesting a good model fit. While the NFI value of 0.833 indicates a fairly good fit of the model to the data, the SRMR value of 0.072 is below the acceptable cutoff of 0.08.

Figure 2 shows the measurement model and

Figure 3, which shows the structural model.

The results from hypothesis testing about the interplay of transactional leadership, human capital, and information sharing are shown in

Table 10. Supporting the first hypothesis, we found that there was a non-direct correlation between transactional leadership and knowledge sharing (

p = 0.052, 0.051, and 0.073 for the sample mean and standard deviation, respectively). With the T-statistic of 0.709 less than the 1.96 threshold and the

p-value of 0.008, this link lacks statistical significance. This implies that there are other elements affecting knowledge sharing than merely transactional leadership. This outcome emphasizes the need to build staff competencies since transactional leadership may not be sufficient to inspire knowledge sharing initiatives without building the required human capital in the firm. The third hypothesis, which looks at how human capital affects knowledge sharing, shows a strong positive association with a starting value of 0.435 and a mean of 0.440, standard deviation of 0.075, and a total of 0.435. Human capital influences knowledge sharing, as shown by a T-statistic of 5.781 and a

p-value of 0.000, both exceeding the 1.96 criterion. Employees that are experts in their fields are more likely to share what they know with their colleagues, which boosts the organization’s capacity for learning and creativity.

The second school of thought investigated how transactional leadership connects to human capital. The original sample value of 0.685, the sample mean of 0.685, and the standard deviation of 0.037 points to a strong and statistically significant positive effect. Indicating statistical significance, this association is highly supported with a

p-value of 0.000 and a T-statistic of 18.484. These results show that, through performance-based rewards, training possibilities, and organized coaching, transactional leadership is quite important in growing human capital. This is consistent with recent research [

78], demonstrating that effective leadership promotes the development of human capital, which therefore generates a workforce more qualified.